The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic has mandated telehealth adaptations. Communication in the pain consultation is a complex interplay of nonverbal visual cues and behaviors. The crucial “therapeutic alliance” can be difficult to establish with telehealth. 1 Although telehealth offers a viable alternative, there are concerns over accessibility, clinical limitations, 2 and benefit. 3 Our secondary care service for chronic pain established a remote telehealth follow‐up clinic in response to the first wave. We set out to retrospectively evaluate the service according to the Faculty of Pain Medicine 4 Standards of Good Consultation. Themes were quality of communication, feeling listened to, self‐help advice, and understanding. 4

Following local audit approval, 71 consecutive patients from May 2020 to July 2020 were screened for eligibility (follow‐up patients, contactable with one telephone call). Sixty‐five attended patients were phoned once by an impartial and anonymous researcher (author R.B.). Patients were from Merseyside and data were anonymized. Thirty‐eight answered and 27 patients consented to the survey over the telephone, whereas 3 of 11 replied to the survey by email. Overall response rate was 78.9%. Data were collated using Microsoft Excel (version 16) and analyzed with GraphPad Prism (version 8). Questions concerning satisfaction using a 5‐point Likert scale were implemented and Wilcoxon rank sum statistics used to compare medians. The standardized effect size was calculated using a bias‐corrected model (Hedges; Figure S1). A binomial test was used to compare observed frequencies to expected. Patients acted as their own controls. Statistical significance was set to p less than 0.05. This work was approved by the local Audit and Research Department and we confirmed the project was a service evaluation (hra‐decisiontools.org.uk/research). Patients gave verbal consent.

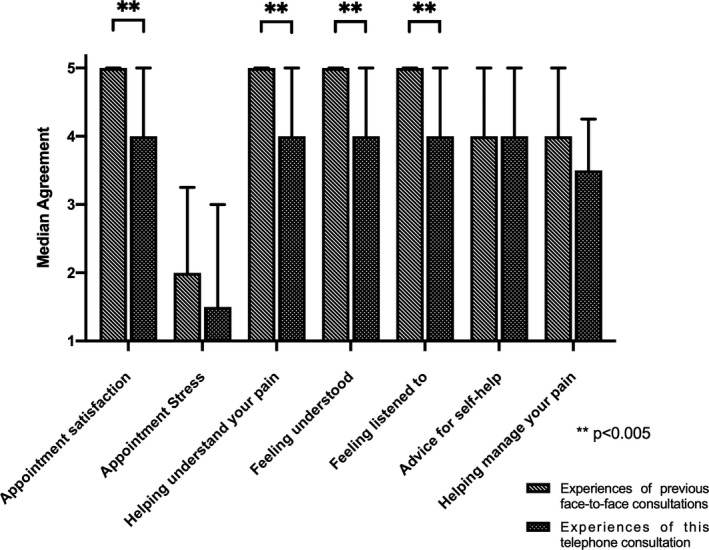

A total of 30 patients were included in the analysis, data for 1 patient was incomplete. Most were women (20/29) with a mean age of 65.7 years (36 to 85 years) and 9 of 29 were men, with a mean age of 67.3 years (47 to 85 years). Regarding International Classification of Disease (ICD)‐11, pain etiology included 24 of 29 musculoskeletal, 7 of 29 neuropathic (5/7 radiculopathy), 1 of 29 chronic primary pain, and 1 of 29 chronic postsurgical. Anatomically, 15 of 29 reported back, 13 of 29 shoulder, 5 of 29 leg, 2 of 29 arm, and 5 of 29 generalized pain. The majority of patients were on long‐term follow‐up (25/29). Figure 1 shows the median scores for experience satisfaction. When asked directly, 14 of 30 patients reported that they expected the experience to be worse, however, this increased to 20 of 30 following the appointment. Of the 20 patients that reported that the telephone was worse than face‐to‐face, 13 of 20 attributed this to communication problems and 8 of 20 to a lack of examination. Communication issues are reflected in verbatim responses: “not easy to be descriptive” and “you can't ‘point things out’ or the clinician cannot ‘see what you are like.’” For 19 of 30 patients, consultations met their needs. We noted that 21 of 30 reported that they were able to say all that they required. However, 25 of 30 of the patients would prefer to have a face‐to‐face appointment and video‐conferencing call for 17 of 30.

FIGURE 1.

Satisfaction patients scored their agreement with the following statements with on a 5‐point Likert scale from 1 (least) to 5 (most). Direct comparisons of the questions for face‐to‐face versus telephone consultations show significance for “Appointment satisfaction,” “Helping you understand your condition,” “Feeling understood,” “Feeling listened to,” and “Advice for self‐help.” * Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 using Wilcoxon rank sum statistics for medians.

Our survey suggests that patients do not prefer telehealth to conventional consultations. Despite the reported satisfaction with both face‐to‐face and telephone appointments, there was a significant reduction in the patient experience ratings around communication and patients reported missed symptom validation from the clinician. Video‐conferencing may provide a solution; however, equipment might not be available or preferred. It should not be assumed that verbal communication is sufficient to assess complex needs, especially for a low socioeconomic demographic. In this regard, the generalizability of our data is limited by our cohort. The literature pre‐COVID‐19 suggests that telehealth is no more efficacious than face‐to‐face 5 and this should be taken into account when we determine future standards of care and training.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.B., K.H., and H.T. designed the study. Data were collected and analyzed by R.B. The manuscript was drafted and edited by R.B., K.H., and H.T.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This work was part of an audit and quality improvement project which was approved by the local Audit and Research Department. The UK Health Research Authority’s research decision tool (hra‐decisiontools.org.uk/research) was consulted to confirm that this project was a service evaluation. Patients were asked by telephone to give verbal consent.

Supporting information

Fig S1: Experiences of face‐to‐face vs. telephone consultation

Funding information

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lafontaine M, Azzi S, Paquette D, et al. Telehealth for patients with chronic pain: exploring a successful and an unsuccessful outcome. J Technol Human Ser. 2018;36:140–60. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eaton LH, Godfrey DS, Langford DJ, Rue T, Tauben DJ, Doorenbos AZ. Telementoring for improving primary care provider knowledge and competence in managing chronic pain: A randomised controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare. 2020;26:21–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mariano TY, Wan L, Edwards RR, Jamison RN. Online teletherapy for chronic pain: A systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2019. 10.1177/1357633X19871746. [Epub ahead of print] . PMID: 31488004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Faculty of Pain Medicine . Conducting quality consultations in pain medicine. London: Faculty of Pain Medicine; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5. O'Brien KM, Hodder RK, Wiggers J, et al. Effectiveness of telephone‐based interventions for managing osteoarthritis and spinal pain: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Peer J. 2018;6:e5846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1: Experiences of face‐to‐face vs. telephone consultation