INTRODUCTION

Persons with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD) are particularly susceptible to consequences from the coronavirus (COVID) pandemic including social isolation, disruption of daily routine, and less direct care due to reductions in nursing home (NH) workforce. Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), such as agitation, depression, and anxiety, which occur in >90% of persons with ADRD have likely been exacerbated by this pandemic. 1 Staffing shortages and implementation of nonpharmacological strategies to treat NPS was challenging prior to COVID—such challenges have likely intensified following the start of the pandemic. Given reductions in staffing and increased behavioral symptoms among residents with ADRD, this may result in greater reliance on psychotropics such as antipsychotics to manage NPS. This analysis evaluated changes in central nervous system (CNS)‐active medication prescribing among all long‐stay NH residents with ADRD within the state of Michigan following the start of the COVID pandemic.

METHODS

Data were drawn from a 100% sample of NH resident assessment data (Minimum Data Set; MDS) from January 1, 2019 to June 30, 2020. We constructed monthly cohorts of long‐stay (≥100 days) NH residents in Michigan who were ≥65 years and diagnosed with ADRD. We determined monthly prevalence of CNS‐active medication prescribing, including the following classes as recorded on MDS assessments: antipsychotic, antianxiety, hypnotic, antidepressant, and opioid prescribing. Prescribing of diuretic medications was evaluated as a comparison medication that would not be anticipated to change during the pandemic.

Medication data were obtained from MDS assessments reporting medications administered in the past 7 days. We fit a two‐phase interrupted time series regression model to evaluate change in trend of medication use controlling for pre‐COVID level and trend. The two phases were: (a) pre‐COVID (January 2019–February 2020) and (b) during COVID (March 2020–June 2020). In sensitivity analyses, we evaluated if results remained consistent among residents overall (i.e., not restricting to residents with ADRD). The study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board. Analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.4.

RESULTS

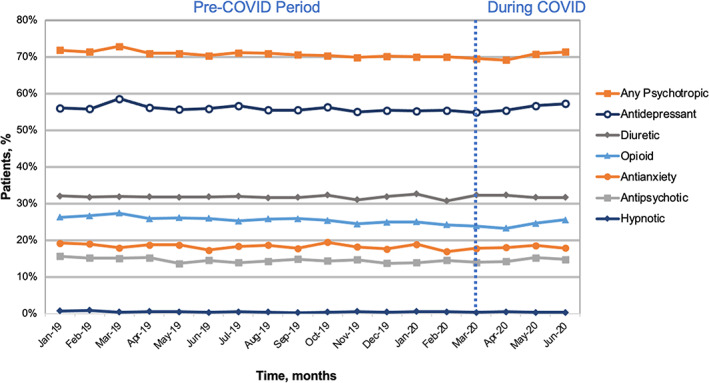

The cohort included 35,922 residents with ADRD across 440 NHs in Michigan. Following the start of COVID, there was no significant change in antipsychotic (slope change = 0.43, p = 0.08), antianxiety (slope change = 0.16, p = 0.60), or hypnotic use (slope change = −0.02, p = 0.78; Table S1, Figure 1). Small but significant increases in antidepressant use were noted compared to pre‐COVID, increasing from 54.8% to 57.2% (slope change = 0.96, p = 0.012). Similarly, there were small increases in opioid use, increasing from 23.9% to 25.6% (slope change = 0.81, p = 0.002). There was no change in diuretic use.

FIGURE 1.

Percent of long‐stay nursing home residents with dementia with central nervous system‐active medication use following the start of the COVID pandemic

For sensitivity analyses, we evaluated whether results remained similar among residents overall not restricting to ADRD (results unchanged).

DISCUSSION

In this sample of NH residents with ADRD in Michigan we found relatively minimal changes in CNS‐active medication use following the start of COVID. There was no increase in antipsychotic use with only minimal increases in antidepressant (2.4%) and opioid (1.7%) use. While these increases in antidepressant and opioid use were statistically significant, it is not a meaningful change in the absolute prescription rate. This differs from recent studies in the United Kingdom 2 and Canada 3 which showed small but significant increases in antipsychotic prescribing following the pandemic. Differences observed may be due in part to regulatory pressures to reduce antipsychotic prescribing in the US NHs through initiatives such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care. 4

Among our study's limitations, use of MDS limits analysis to medication classes included in the assessment (e.g., excluded antiepileptics) and excludes use that occurs in between assessments. Lastly, we do not know prescribing indication or appropriateness.

Increases in antidepressant use may reflect treatment of anxiety, depression, or off‐label use for NPS. A June 2020 survey of US adults without dementia found that the prevalence of symptoms of anxiety has increased threefold and depression has increased fourfold compared to the previous year. 5 Reports from prescription benefit plan Express Scripts documented a nearly 20% increase in antidepressant prescribing following the start of COVID. 6 It is not surprising that these trends would also extend to NH residents with ADRD. As the pandemic continues, it is important characterize the impact on behavioral symptom burden among NH residents and avoid medication‐related harms which can further contribute to mortality during the pandemic.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have none to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lauren B. Gerlach had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Lauren B. Gerlach, Theresa I. Shireman, and Julie P.W. Bynum. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Lauren B. Gerlach, Theresa I. Shireman, and Julie P.W. Bynum. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: Pil S. Park. Obtaining funding: Theresa I. Shireman and Julie P.W. Bynum. Administrative, technical, or material support: Julie P.W. Bynum. Supervision: Lauren B. Gerlach and Julie P.W. Bynum.

SPONSOR'S ROLE

The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supporting information

Table S1 Rates and trends in monthly CNS‐active and comparison medication use among long‐stay nursing home residents with dementia

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging P01AG027296 and K23AG066864.

Funding informationNational Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Numbers: K23AG066864, P01AG027296

Funding information National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Numbers: K23AG066864, P01AG027296

REFERENCES

- 1. Canevelli M, Valletta M, Toccaceli Blasi M, et al. Facing dementia during the COVID‐19 outbreak. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8):1673‐1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Howard R, Burns A, Schneider L. Antipsychotic prescribing to people with dementia during COVID‐19. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(11):892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stall NM, Zipursky JS, Rangrej J, et al. Assessment of psychotropic drug prescribing among nursing home residents in Ontario, Canada, during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2021:e210224. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Data show National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care achieves goals to reduce unnecessary antipsychotic medications in nursing homes. October 2017. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact‐sheets/data‐show‐national‐partnership‐improve‐dementia‐care‐achieves‐goals‐reduce‐unnecessary‐antipsychotic. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 5. Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID‐19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1049‐1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. America's State of Mind Report . Express Scripts. April 16, 2020. https://www.express‐scripts.com/corporate/americas‐state‐of‐mind‐report. Accessed on August 24, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Rates and trends in monthly CNS‐active and comparison medication use among long‐stay nursing home residents with dementia