Abstract

International research collaborators conducted research investigating sociocultural responses to the Covid‐19 pandemic.

Our mixed methods research design includes surveys and interviews conducted between March and September of 2020 including 249 of 506 survey responses and 18 of 50 in‐depth, exploratory, semi‐structured interviews with self‐defined politically left‐leaning women in the United States. We employ a sequential design to analyze statistical and qualitative data.

Despite international data suggesting that trust in federal governments reduces anxiety, women who did not trust and actively opposed the Trump administration reported lower levels of anxiety than expected. Results indicate reliance on and development of new forms of connection that seem to mitigate symptomatic anxieties when living in opposition. Women living in opposition to the leadership of the federal government use and develop resources to help them cope. Research on coping strategies and mental health and anxiety during crisis can inform recommendations for ways to support and strengthen sense of coherence during tumultuous times.

Keywords: anxiety, Covid‐19, health equity, mixed methods, pandemic, politics, women

1. INTRODUCTION

Nearly a year after the discovery of Covid‐19, the pandemic continues to present severe global challenges to health and life (Perez Perez & Bezmin Abadi, 2020). Impacts are different across and within geographic regions and demographic groups causing unequal rates of infection and death (Shadmi et al., 2020; Shams et al., 2020). National and local mandates for health behaviors vary widely across the globe. In the United States the response to Covid‐19 was, and in some ways continues to be, highly politicized as two distinct groups stood for and against following health guidelines. Initially in spring of 2020, Republican leaders resisted health directives by publicly associating mask mandates and business closures as challenges to individual freedom and a functioning economy. Democrat and Progressive leaders quickly and consistently aligned themselves with medical and scientific calls to mandate health guidelines to curb the spread of the virus and protect those at risk (Samore et al., 2020). In addition to obvious risks to health and life, the pandemic continues to result in distress among the public related to political divisions and violence of inequality of poverty, racism, policing, and unequal access to health that results in lives lost. People of color are more likely to die of Covid‐19 than white counterparts, and men are slightly more likely to die than women. These data, however, do not fully encompass the range of experiences and long‐term consequences that accompany unequal outcomes especially with regard to gender (Davies et al., 2020). Researchers are quickly documenting where and how measurable consequences of the pandemic are impacting individuals and communities across the globe. In this quickly changing time it is clear that research on social consequences of the pandemic must include foci on personal and community level strategies for wellness and on larger political and economic structures within national landscapes to be constructive. Quite simply, politics matter when it comes to health and life. To explore gendered responses to living during the pandemic under the Trump administration we employed complementary frameworks of Salutogenesis and Critical Medical Anthropology (CMA).

1.1. Salutogenesis

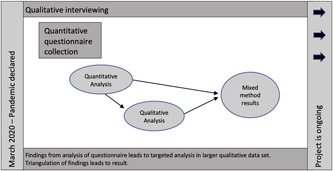

Social scientists have conducted research on social isolation and connection as important aspects of health for decades. As the pandemic continues, the literature continues to grow, documenting impacts of the virus as well as quarantine and isolation on well‐being and anxiety. The salutogenic model (Antonovsky, 1987) is one approach to understanding how humans cope with life challenges through development of a sense of coherence (SOC). SOC is a health‐promoting factor which expresses an individual worldview with three components: comprehensibility (the extent to which stimuli from one's external and internal environment are perceived as structured, explicable, and predictable), manageability (the extent to which resources are perceived as available to a person to meet the demands posed by these stimuli), and meaningfulness (the extent to which these demands are perceived as challenges, worthy of investment and engagement). According to this model, people who develop a strong SOC perceive the world as understandable, manageable, and meaningful and this perception will help them to better identify and use resources to cope with stress and crisis (Antonovsky, 1987). A measurably strong SOC is thought to enable people to cope with stressful life events while maintaining physical and mental health (Lindström & Eriksson, 2006). A sense of national coherence (SONC) is defined as an enduring tendency to perceive one's national group as comprehensible, meaningful, and manageable (Mana et al., 2019). How people make sense of living in a place and during a time when they do not trust local or federal governments to provide instructions, information, and resources effectively during a global health crisis is important (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mixed methods analysis design

Previous studies suggest that trust in governmental institutions mitigates negative impacts of crises on mental health and that mistrust in powerful institutions can result in negative consequences (Cheung & Tse, 2008; Thoresen et al., 2018). SOC and SONC have also been shown to be correlated with better mental health and lower anxiety in different social contexts during the Covid‐19 crisis (Mana & Sagy, 2020).

1.2. Critical medical anthropology

CMA emerged as a response to medical anthropology's rootedness in a single biomedical perspective (Baer et al., 1986; Singer & Baer, 2018). CMA provides a framework for understanding health and illness through a critical lens that incorporates attention to political and economic structures into understandings of power, inequality, and health (Singer & Baer 1995, 2018; Panter‐Brick & Eggerman, 2018). Global theories of social structure inform the development and ongoing use of CMA (Sesia et al., 2020). The interplay between institutional processes and lived experience is a key subject of analysis, including investigations of how political and economic processes impact inequality, perceptions, and practices of the body (Sharp, 2000; Kleinman et al., 1997; Scheper‐Hughes & Lock, 1987), illness, health, and social suffering (Kleinman et al., 1997).

While the framework considers these larger structural forces, scholars also use it to explore lived experiences (Singer et al., 1992) through qualitative inquiry and, notably, illness narratives (Kleinman, 1988). Attending to the richness of lived experiences through qualitative inquiry allows for in‐depth exploration of everyday lives while also incorporating and intertwining analyses of structural forces of inequality and institutional power that play out through systems of immigration, legal and geographic dispossession, economic vulnerabilities, climate crises, etc. CMA and salutogenesis perspectives can work together in some areas through investigation and analysis of interwoven social relationships with a focus on trust, connectedness, and health and well‐being during political crises.

The use of a CMA framework also includes attention to different and related inequalities. Instead of a focus on a single identity as a marker of vulnerability analyses of multiple “axes of power” or social factors including gender, economics, ethnicity, allow for an investigation of “a political economy of brutality” (Farmer, 1996; 2003). Drawing on CMA, Syndemics also posit that upstream causes of inequality cluster together to exacerbate risks and vulnerabilities (Singer et al., 2017; Willen et al., 2017). The use of syndemics and structural violence are useful in understanding exposed inequalities and additional factors of health (Singer & Rylko‐Bauer, 2020). Each construct recognizes gender is a crucial axis, entangled with others, whereby structural oppression impacts people differently. Critical medical anthropologists quickly responded to the pandemic with an avalanche of new research projects and articles applying the perspectives and insights from the field.

Researchers across the sciences have also already published insights on the impact of the pandemic on women worldwide suggesting higher risks among women than men of psychological impact of the pandemic in China (Wang, Pan, et al., 2020), the Philippines (Tee et al., 2020), and Poland (Wang, Chudzicka‐Czupała, et al., 2020). While gender is only one example of multiple entanglements and axes of power, it is one that requires research and analysis regarding Covid‐19. There are current calls for evaluation of the impact of gender on health outcomes based on prior pandemics as well as early evidence of differences in outcomes (Connor et al., 2020; Wenham et al., 2020). Recent researchers have identified gender‐based differences in Covid‐19 transmission and have called for research that considers gender (Connor et al., 2020). Early findings also indicate girls and women are experiencing crucial inequities due to gender‐based violence, access to healthcare, and unwanted pregnancy associated with lockdowns and pressure on healthcare systems that are no longer providing routine care (Cousins, 2020). While men are slightly more likely to die of Covid‐19, researchers also predict deleterious impacts on women worldwide as they endure other syndemic vulnerabilities (Burki, 2020). There is still little research exploring the impact of the pandemic on other genders including but not limited to genderqueer, trans, nonbinary, and two spirit, research that is also crucially needed.

In the United States, researchers are also rapidly exploring gender as a locus for untangling immediate and long term impacts of Covid‐19. Davis Floyd, for example, is investigating the impact of the pandemic on pregnancy and structural vulnerability (Davis‐Floyd et al., 2020). Additional work on structural vulnerabilities within the states and globally related to Covid‐19 is also of interest to critical medical anthropologists focusing on the present pandemic (Team & Manderson, 2020) and has also been a focus in past epidemics (Abramowitz, 2017).

Focusing on only women is a first step toward a more inclusive understanding of all genders including trans, nonbinary, and other genders; however, it is important to evaluate how external economic pressure creates care work as inherently gendered and, therefore, increases risk of viral transmission among women (Davies et al., 2020). We do not distinguish between women with different identities here, such as Queer, Trans, Black, Indigenous, People of Color, and these differences are essential to understanding health and risks (Connor et al., 2020). We view this analysis, based on our available data, as a first step in understanding gender and Covid‐19 and believe a more nuanced intersectional analysis of all genders along with other axes of power is needed in future studies.

This study attends to the need for continued analyses of gendered impacts of Covid‐19 by elucidating strategies that women chose and/or developed to increase their levels of connectedness to buffer anxiety and maintain mental health. Results of this research add to the growing literature of coping with large scale crisis even when misaligned with a federal government, identify possible areas for health interventions, and further inquiry about slowing viral spread.

1.3. Connectedness

Research on connectedness is crucial during a time of pandemic isolation and quarantine. Social research on connectedness also frames our study and our analysis by focusing on how people manage competing risks of mental health impacts of isolation and the virus itself. These risks are exacerbated in groups of people who live with higher levels of health inequity related to intertwining factors of racism, poverty, stress, and other forms of violence (Watson et al., 2020).

Social scientists are well positioned to conduct research on impacts of social isolation and connection based on a long history of investigation of this topic. Social networks, social integration, and social support have all been shown to impact well‐being (Howick et al., 2019; Tsai & Papachristos, 2015). Connections can be productive and protective for health and survival and/or dangerous for health and life, depending on the type of connections and social networks. Social support is a coping resource that can act as a buffer against adverse life events and to support mental health in times of crisis (Guruge et al., 2015; Milner et al., 2016; Srensen et al., 2011). Research has already explored current and projected risks associated with mental health problems related to isolation and experiences of connection, disconnection and resilience during the pandemic (Amorin‐Woods et al., 2020; Hardy, 2020; Pantell & Shields‐Zeeman, 2020).

2. BACKGROUND

The setting for the Covid‐19 pandemic in the United States during the spring and summer of 2020 was unrest and anxiety under contested federal leadership. The region of the United States denotes a national identity though the nation contains multiple shifting and contingent identities and sovereign tribal nations. Anxieties and negotiations of place, health, and identity continued to be present as a major contentious national election drew near. The authors collaborated to understand impacts of the pandemic as part of a large international study by working together to disseminate an international survey in the United States and analyze results of in‐depth qualitative interviews.

Early analysis of survey results showed that respondents who identified as women who had political affiliations that were not in alignment with the current federal leadership reported better coherence, lower anxiety, and better mental health than expected despite reporting intense stress related to the Trump administration's decision‐making and actions of the political right in interviews. This exploratory finding was surprising to researchers who expected to see higher anxiety levels related to lower trust in government and led researchers to select and evaluate data from left‐leaning women in the United States to understand practices for well‐being. These women use and develop generative social connections during this multi‐leveled global and national crisis.

3. METHODS AND ANALYSIS

We used multiple data collection methods to incorporate salutogenesis and CMA through a concurrent, mixed methods strategy of using surveys and interviews. We analyzed each dataset separately and then invoked a sequential exploratory analysis design to explore and triangulate findings (Creswell, 2007). All research activities are covered under an active Institutional Review Board protocol.

3.1. Surveys

Survey development is based on the salutogenic model and explored coping resources: SOC (SOC‐13, Antonovsky, 1987), SONC (Mana et al., 2019), level of trust in relevant institutions (i.e., media, legal courts, the president, Centers for Disease Control, police, the government, health‐care workers, and hospitals) and one's perceptions of the social support one receives in the time of crisis from one's social circles (family, community, friends, social media, work colleagues), as predictors of levels of mental health (MHC‐SF, Lamers et al., 2011) and general anxiety (GAD‐7, Spitzer et al., 2006) (Mana & Sagy, 2020). Surveys of this type are used to explore SOC and SONC in a large dataset that can be quantitatively measured and compared across nation state allegiances and borders (Mana et al., 2021). For the current study we used multiple regression analysis and Pearson correlation analyses to explore the relationships between the coping resources and mental health and anxiety in a sample of 249 women who declare that they voted for a left‐leaning party in the last election.

3.2. Interviews

Researchers designed an open‐ended and exploratory interview guide using a semi‐structured approach asking participants about perceptions of pandemic response and the virus, coping strategies, fears, and other domains. Inductive and exploratory interviews of this type allow interviewers to facilitate open inquiry by listening to participant perspectives on what is important to them and the way that they make meaning in the world (Bernard, 2017). We selected this method intentionally to explore a rapidly unfolding situation, the magnitude of which we could not predict. The extended interviews allowed for in‐depth and inductive inquiry attending to the lived experiences of people in the pandemic and several deductive questions about Covid‐19. Phone interviews were conversational with several closed‐ended questions asking people to respond to phrases and questions. Audio‐recorded discussions lasted between 30 and 120 min. Interviewers took detailed notes and transcribed interviews in full. At the time of this writing we conducted 50 interviews, including 18 left‐leaning Democrat or Progressive women. We used inductive approach to develop and revise a codebook using a strategy for inter‐rater reliability and applied codes using Atlas.ti.

3.3. Sampling

Survey dissemination occurred through snowball sampling with personal contacts first and a large wave of social media recruitment in the days that followed. We recruited interview participants through convenience sampling and shifting toward theoretical sampling designed to diversify the dataset.

4. RESULTS

Two regression analyses were conducted on 249 survey responses out of 500 (selected for left‐leaning women). At the first analysis levels of mental health were entered as a dependent variable and levels of general anxiety were entered as a dependent variable at the second analysis. The coping resources of SOC, SONC, social support and trust, were entered as predictors. The two models were significant (R 2 = .53, F(4,157) = 44.13, p < .001; R 2 = .43, F(4,155) = 29.63, p < .001, accordingly). SOC and social support significantly predicted mental health (b = .48, t(157) = 7.38, p < .001; b = .35, t(157) = 5.37, p < .001, accordingly), while SONC and trust were not significant. The second regression analysis revealed that that level of SOC significantly predicted levels of general anxiety (b = –.54, t(155) = −7.54, p < .001) while SONC, social support, and trust did not significantly predict levels of anxiety.

According to Antonovsky (1987), Individuals with stronger SOC can rely on and use state and federal agencies to facilitate the coping with stressors. However, quantitative results revealed that left‐wing women did not use SONC and trust (especially in agencies that have a direct responsibility for controlling the pandemic) as effective coping resources. Qualitative research demonstrated how left‐leaning women searched for other coping resources in their surroundings in the absence of trust in political leaders.

To better understand the role of trust in American institutions for SOC, SONC, mental health, and anxiety, we conducted Pearson correlation analyses (see Table 1). The findings reveal that trust in legal courts, police, the government, economy, and media are related to a strong SOC, SONC, better mental health, and low levels of anxiety. However, the trust in national level institutions—the president, Centers for Disease Control, hospitals and healthcare providers—were less relevant and did not correlate with levels of SOC, SONC, mental health, and anxiety. This group of women had low levels of trust and SONC and better mental health and lower anxiety than predicted. These findings led to the analysis of the qualitative results to further investigate coping strategies.

Table 1.

Structured and self‐reported questionnaires

| The Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD‐7, Spitzer et al., 2006). 7‐ Items of this scale enquired about the degree to which the participant has been bothered by feeling nervous, anxious, worried, restless, annoyed, and afraid during the 2 weeks before answering the questionnaire. Researchers used a 4‐point Likert scale (0–3) to score these questions, with total scores ranging from 0 to 21. Higher scores reflect greater severity of anxiety. Internal consistency of the questionnaire was estimated at 0.89 (20) and in the current study α = .91, .85, .88, .90. |

| Mental Health Continuum (MHC‐SF, Lamers et al., 2011). This scale includes 14‐items measuring the three components of well‐being: emotional, social, and psychological. Researchers adapted the questions to the current context and created a scale based on experiences the participants had over the last 2 weeks (never, once in these 2 weeks, about once a week, two or three times a week, almost every day, or every day). Internal consistency of the questionnaire was estimated at 0.89 (7) and in the current study α = .90, .89, .91, .94. |

| Sense of Coherence (SOC‐13, Antonovsky, 1987). 13 Items, on a 7‐point Likert scale, explore participants' perceptions of the world as comprehensible, meaningful, and manageable. The α values in former studies using SOC‐13 range from 0.70 to 0.92 (22) and in this study the α = .79, .85, .81, .82. |

| Sense of National Coherence (SONC, ‐authors‐). 8‐Items on a 7‐point Likert scale (1 = totally agree, 7 = totally disagree) explore the participants' perceptions of his/her own society as comprehensible, meaningful, and manageable. Internal consistency of the questionnaire was estimated at 0.80 (11) and in the current study α = .84, .70, .77, .81. |

| Trust in governmental and other institutions. A 7‐item questionnaire regarding level of trust in relevant institutions (i.e., media, president, police, government, economy, health department/authorities, health‐care workers, and hospitals) on a 5‐point Likert scale (1 = very much, 5 = not at all). Internal consistency was α = .77, .85, .85, .86. |

| Social Support. Three items explored feelings of support that the participant feels they receive from family members, from the community in the neighborhood, and from virtual communities (i.e., social networks, Twitter, Facebook), on a 5 point Likert scale (1 = very much, 5 = not at all). |

| Level of risk and exposure to Covid‐19. We explored both health and financial risk by asking if the participant: (1) was part of a risk group because of their age and/or medical condition; (2) had been in quarantine; and (3) had been diagnosed with Covid‐19. We also explored the participant's estimation of financial risk: To what extent do you think you will suffer financially from the Corona virus crisis? (1 = very low, 5 = very high). |

| Socio‐demographic variables: Researchers collected demographic data on gender, SES, ethnicity, religion, and political affiliation. |

Participants in this group spoke of connection as a priority while also expounding on profound mistrust of the federal government. When reflecting on local and global responses to the pandemic, women focused on local and national response and compared these responses to other countries like New Zealand with women leaders who they perceived to be handling the pandemic much more effectively. At the center of these strategies, women prioritized connection with themselves and others.

4.1. Mistrust

People in this group clearly conveyed disgust and anger over the actions of Trump and others at the federal level. Some women noted that their mayors or governors were reacting effectively, but all noted that they did not trust and notably feared the Trump Administration. Ronda (all names are pseudonyms), said, “a second Hitler…Trump is not far from that. I am not safe. My kids are not safe and that's scary. Really really really scary. Someone that has lived free for her whole life has something like this coming up in her head.” Other participants echoed these ideas throughout interviews. Each woman shared a general sense of being unsafe. Fears centered on Trump as a dangerous, dictator‐like figure whose actions blocked the ability of other people and institutions to function well:

Now civil service people in the United States, the regular department heads of HHS [Health and Human Services], the regular departments of the national park service, all of those people have been doing what they can. But they are knee‐capped by supervisors put in place by this administration and pressure the administration puts on them. They all get a C‐. The president and this administration absolutely failed this country.

In addition to lack of trust, women talked about an awareness of the global stage. Many expressed embarrassment over how the United States looks to the rest of the world. Anna said, “Other countries pity us. America burns while Trump tweets. That this whole situation has been so much worse than it needed to be…the federal response and leadership has been so lacking. Tens of thousands of people are dying, have died, will die that did not need to.” Anxiety about the health and safety of people in the country and the place of the country in the global setting were both significant. Our data indicate that connections with others, both real and imagined, help to offset these anxieties and improve mental health.

“Everybody's very eager to be connected now”

While anxiety about national and international pandemic response are clear, this group mitigates that anxiety through connection. The first level of connection these women discussed was social and familial connections across distance through deepening relationships and reconnecting with loved ones. Many discussed technologically‐enabled dance parties, happy hours, writing and prayer groups, and group chats. When asked what has helped, connections were always prominent. “Eating dinners together helps. Emailing some of my friends helps.” Those with primary partners discussed relationships as key to their wellness:

Those of us who feel like we have strong relationships at home, and we love our partners and at this time we are working together. That feels really good. This—this is a time when whatever you have gets magnified. If you have a good relationship to start with it feels really good…

Even those who discussed difficulties in family relationships talked about appreciating changes. Ruth talked about marital problems that were exacerbated by the pandemic and then changed into a resolution: “I am happy to say that I really came up with a different way of understanding our marriage… Who knew after 50 years of marriage you could think of new ways to think about something?”

Connections through networks of care are also important to these women. As time passes, interviewees are more likely to have had or been close to someone with Covid‐19. People recount both doing things for others like dropping off groceries, and gratitude for others who helped them in similar ways. Laila, a woman who tested positive, commented, “new communities…developed so, like, I have met and become friends with lots of new people who have reached out to me through various stages who relate tangentially or [are] related in some way, people helping and supporting each other. Dropping off food.” Sam who had a presumed case of Covid‐19 said that she noticed, “more people reaching out to say, ‘hey are you ok?’” Some shifted between being caregivers to needing help and back to being caregivers again as they became sick and recovered.

These women also expressed limitations on their ability to care for others the way they wanted to while observing virus control guidelines. Women talked about desires to have eye contact, close proximity, and physical interaction while adhering to necessary health precautions like distancing and living through quarantine. Talia recounted a story of comforting a neighbor who is an engineer with young children at home:

…[the neighbor] has been going crazy and I have a pretty good sense of what is going on in their house. She said, “I am not a stay at home mom for a reason.” One evening she was out front, and she started talking to me and started crying and I just leaned over and gave her a hug. I didn't even think about it. To be able to respond with a hug is something I really miss.

Jada talked about being “touch starved” through isolation and the need to reach out more through packages and letters. These connections were also important to women who wanted to extend compassion and feel connected to others who had different situations through comparison and empathy. Janna said, “I'm giving everyone a little extra grace.”

Connections also took the form of comfort drawn from the imagined experiences of others. Some women stated that they were comforted by the fact that others were experiencing the same thing: “Everyone around the world is in the same boat.” Others spoke about their experiences as privilege and acknowledged others who might be suffering more: “…also my privilege right? For someone else they can't get food for the week, they can't make their care payment…and so it [is] just really so layered, the effects of this. There is nothing that it doesn't touch.”

Women discussed solitary and social gratitude activities that help them to remain connected as well, slow and quiet activities such as drinking tea, practicing yoga, and taking time to think of others. Two interviewees talked about fasting in prayer as a way to “take a moment and think about others.” Hopefulness is not just about their own future, but also the future of others in the world. Chara said:

I am an optimist. I'm really hopeful that something big comes out of this time. Whether it is … working on this innovation design tech thing that transforms our world that we just don't even know about yet. Or we realize that the education system is … broken…or like this tremendous leader emerges like Martin Luther King stature that emerges from this. I am hopeful that something really big is going to come out of this.

Like Chara, other women expressed a connected hopefulness that the world would be better for all people. It is through direct and symbolic connections with one another that women on the left are finding coherence and connection despite political anxiety and unrest in the United States.

5. DISCUSSION

The results of both surveys and interviews with left‐leaning women in the United States indicate an important aspect of coping during a pandemic. These women worry about a federal government that they do not trust, yet they relied on other resources like their personal SOC and different forms of connection.

It is also true that women and likely other nonmale genders who are performing roles of caretaking and connection have an increased risk of exposure. Women may be more likely to be front line caregivers (Connor et al., 2020; Gausman & Langer, 2020; Wenham et al., 2020) and may have less access to job flexibility that would allow them to refuse caregiving tasks. Socially mediated responsibility and desire to connect may be resulting in higher risk of transmission among women. Lower paying jobs that are available to women also tend to be those that have less control and higher expectations for caregiving of others. Women who contract Covid‐19 may also be more likely to experience long‐term health consequences that will undoubtedly have debilitating impacts of economic well‐being and survival (Yong, 2020). Research in this area must continue to explore the ways that culturally mediated gender roles and desires of people to connect intersect with the vast complexity of bodies and biology associated with gender as not only a focal point but also part of a web of interconnected factors. A limitation to the findings in this study is the lack of a fine grained analysis of the socioeconomic standing, ethnicity, geographic location, sexual identity, and other factors that are included in the category of “women.” Nevertheless, we hope to contribute to multiple studies documenting pandemic impacts. this Future pandemic response for those living with multiple layers of anxiety might focus on connectedness while also focusing on in‐person connections through workplace and personal outreach and gendered assumptions of caregiving as a place for intervention and support.

6. CONCLUSION

Women living in opposition to the political leadership in the United States engage coping strategies to maintain their mental health based on different levels of connection. These coping mechanisms may exacerbate risk for contact and transmission. Insights from this research are useful for understanding how behavioral health practitioners and public health professionals can support programs and practices that enhance SOC and connection for people who do not trust state and or federal government. Results also reflect the literature on social connection and SOC by presenting another example of how connection and cohesion can serve to reduce anxiety and increase mental health for people even when living in opposition to their current political and economic landscape. Women with strong SOC are able to develop coping strategies that help them to maintain their mental health and lower their anxiety despite a lack of trust in federal leadership by using social resources to maintain connections. Results provide another example of how people enact generative and creative means for finding connection and wellness while facing the two‐barreled crises of a pandemic within a nation experiencing significant political strife.

PEER REVIEW

“The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/jcop.22544”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to recognize the time and thoughtfulness of people who agreed to participate in this research. This work is also enriched by our partnerships with international researchers working in multiple countries, and the CoRecovered support group. The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for carefully reading and helping us to improve this version of the work. The authors also gratefully acknowledge project support from Northern Arizona University's office of the Vice President and the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, and the use of services and facilities of the Southwest Health Equity Research Collaborative (U54MD012388).

Hardy, L. J. , Mana, A. , Mundell, L. , Benheim, S. , Morales, K. T. , & Sagy, S. (2021). Living in opposition: How women in the United States cope in spite of mistrust of federal leadership during the pandemic of Covid‐19. J Community Psychol, 49, 2059–2070. 10.1002/jcop.22544

All research is covered under Institutional Review Board approved Project number 1578410‐6.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Due to the nature of the qualitative research in this study, participants did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available. However, quantitative analysis results may be available by contacting Dr. Mana at manna.adi@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- Abramowitz, S. (2017). Epidemics (especially Ebola). Annual Review of Anthropology, 46, 421–445. 10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116-041616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amorin‐Woods, D. , Fraenkel, P. , Mosconi, A. , Nisse, M. , & Munoz, S. (2020). Family therapy and COVID‐19: International reflections during the pandemic from systemic therapists across the globe. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 41(2), 114–132. 10.1002/anzf.1416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. Jossey‐Bass.

- Baer, H. A. , Singer, M. , & Johnsen, J. (1986). Toward a critical medical anthropology. Social Science & Medicine, 23(2), 95–98. 10.1016/0277-9536(86)90358-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, R. (2017). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Rowman Altamira. [Google Scholar]

- Burki, T. (2020). The indirect impact of COVID‐19 on women. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20(8), 904–905. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30568-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C. , & Tse, J. W. (2008). Institutional trust as a determinant of anxiety during the SARS crisis in Hong Kong. Social Work in Public Health, 23(5), 41–54. 10.1080/19371910802053224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor, J. , Madhavan, S. , Mokashi, M. , Amanuel, H. , Johnson, N. R. , Pace, L. E. , & Bartz, D. (2020). Health risks and outcomes that disproportionately affect women during the Covid‐19 pandemic: A review. Social Science & Medicine, 266, 113364. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, S. (2020). COVID‐19 has “devastating” effect on women and girls. The Lancet, 396. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31679-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S. E. , Harman, S. , True, J. , & Wenham, C. (2020). Why gender matters in the impact and recovery from Covid‐19. The Interpreter. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/why-gender-matters-impact-and-recovery-covid-19

- Davis‐Floyd, R., Gutschow, K. , & Schwartz, D. A. (2020). Pregnancy, birth and the COVID‐19 pandemic in the United States. Medical Anthropology, 39(5), 413–427. 10.1080/01459740.2020.1761804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, P. (1996). On suffering and structural violence: A view from below. Daedalus, 125(1), 261–283. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027362 [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, P. (2003). Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor. University of California Press; ISBN‐13: 978‐0520243262. [Google Scholar]

- Gausman, J. , & Langer, A. (2020). Sex and gender disparities in the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Women's Health, 29(4), 465–466. 10.1089/jwh.2020.8472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guruge, S. , Thomson, M. S. , George, U. , & Chaze, F. (2015). Social support, social conflict, and immigrant women's mental health in a Canadian context: A scoping review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22(9), 655–667. 10.1111/jpm.12216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, L. J. (2020). Connection, Contagion, and COVID‐19. Medical Anthropology, 39(8), 655–659. 10.1080/01459740.2020.1814773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howick, J. , Kelly, P. , & Kelly, M. (2019). Establishing a causal link between social relationships and health using the Bradford Hill Guidelines. SSM—Population Health, 8, 100402. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman, A. (1988). Illness narratives: Suffering, healing, and the human condition. Basic Books. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman, A. , Das, V. & Lock, M. (1997). Social suffering. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lamers, S. M. A. , Westerhof, G. J. , Bohlmeijer, E. T. , ten Klooster, P. M. , & Keyes, C. L. M. (2011). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the mental health Continuum‐Short Form (MHC‐SF). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(1), 99–110. 10.1002/jclp.20741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindström, B. , & Eriksson, M. (2006). Contextualizing salutogenesis and Antonovsky in public health development. Health Promotion International, 21(3), 238–244. 10.1093/heapro/dal016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mana, A. , & Sagy, S. (2020). Brief report: Can political orientation explain mental health in the time of a global pandemic? Voting patterns, personal and national coping resources, and mental health during the Coronavirus crisis. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 39(3), 187–193. 10.1521/jscp.2020.39.3.165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mana, A. , Sagy, S. , & Srour, A. (2019). Sense of National Coherence and openness to the “other's” collective narratives: The case of the Israeli‐Palestinian conflict. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 25(3), 226–233. 10.1037/pac0000391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mana A., Super, S. , Sardu, C. , Juvinya Canal, D. , Neuman, M. , & Sagy, S. (in press 2021). Individual, social, and national coping resources and their relationships with mental health and anxiety: A comparative study in Israel, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands during the Coronavirus pandemic. Global Health Promotion, 175797592199295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner, A. , Krnjacki, L. , & LaMontagne, A. D. (2016). Age and gender differences in the influence of social support on mental health: A longitudinal fixed‐effects analysis using 13 annual waves of the HILDA cohort. Public Heath, 140, 172–178. 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantell, M. S. , & Shields‐Zeeman, L. (2020). Maintaining social connections in the setting of COVID‐19 social distancing: A call to action. American Journal of Public Health, 110(9), 1367–1368. 10.2105/ajph.2020.305844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter‐Brick, C. , & Eggerman, M. (2018). The field of medical anthropology in Social Science & Medicine. Social Science & Medicine, 196, 233–239. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Perez, G. I. , & Bezmin Abadi, A. T. (2020). Ongoing challenges faced in the global control of COVID‐19 pandemic. Archives of Medical Research, 51(6), 574–576. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samore, T. , Fessler, D. M. , Sparks, A. M. , & Holbrook, C. (2020). Of pathogens and party lines: Social conservatism positively associates with COVID‐19 precautions among U.S. Democrats but not Republicans. PsyArXiv. 10.31234/osf.io/9zsvb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper‐Hughes, N. , & Lock, M. M. (1987). The mindful body: A prolegomenon to future work in medical anthropology. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 1, 6–41. 10.1525/maq.1987.1.1.02a00020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sesia, P. M. , Gamlin, J. , Gibbon, S. , & Berrio, L. (2020). Introduction. In (Eds.) Gamlin, J. , Gibbon, S. , Sesia, P. M. & Berrio, L. , Critical Medical Anthropology: Perspectives in and from Latin America (pp. 1–16). UCL Press. 10.14324/111.9781787355828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shadmi, E. , Chen, Y. , Dourado, I. , Faran‐Perach, I. , Furler, J. , Hangoma, P. , Hanvoravongchai, P. , Obando, C. , Petrosyan, V. , Rao, K. D. , Ruano, A. L. , Shi, L. , de Souza, L. E. , Spitzer‐Shohat, S. , Sturgiss, E. , Suphanchaimat, R. , Uribe, M. V. , & Willems, S. (2020). Health equity and COVID‐19: Global perspectives. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(1), 1–16. 10.1186/s12939-020-01218-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shams, S. A. , Haleem, A. , & Javaid, M. (2020). Analyzing COVID‐19 pandemic for unequal distribution of tests, identified cases, deaths, and fatality rates in the top 18 countries. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 14(5), 953–961. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, L. A. (2000). The commodification of the body and its parts. Annual Review of Anthropology, 29, 287–328. 10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer, M. , & Baer, H. (1995). Critical Medical Anthropology, Baywood Publishing Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, M. , & Baer, H. (2018). Critical Medical Anthropology. Critical approaches in the health social science series (2nd ed.). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Singer, M. , Bulled, N. , Ostrach, B. , & Mendenhall, E. (2017). Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. The Lancet, 389, 941–950. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30003-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer, M. , & Rylko‐Bauer, B. (2020). The syndemics and the structural violence of the COVID‐19 pandemic: Anthropological insights on a crisis. Open Anthropological Resources, 1(1), 7–32. 10.1515/opan-2020-0100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singer, M. , Valentin, F. , Baer, H. , & Jia, Z. (1992). Why does Juan García have a drinking problem? The perspective of critical medical anthropology. Medical Anthropology, 14(1), 77–108. 10.1080/01459740.1992.9966067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R. L. , Kroenke, K. , Williams, J. B. W. , & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD‐7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srensen, T. , Klungsyr, O. , Kleiner, R. , & Klepp, O. M. (2011). Social support and sense of coherence: Independent, shared and interaction relationships with life stress and mental health. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 13(1), 27–44. 10.1080/14623730.2011.9715648 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Team, V. , & Manderson, L. (2020). How COVID‐19 reveals structures of vulnerability. Medical Anthropology, 39(8), 671–674. 10.1080/01459740.2020.1830281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee, M. L. , Tee, C. A. , Anlacan, J. P. , Aligam, K. J. G. , Reyes, P. W. C. , Kuruchittham, V. , & Ho, R. C. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID‐19 pandemic in the Philippines. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 379–391. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoresen, S. , Birkeland, M. S. , Wentzel‐Larsen, T. , & Blix, I. (2018). Loss of trust may never heal. Institutional trust in disaster victims in a long‐term perspective: Associations with social support and mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1204. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, A. C. , & Papachristos, A. V. (2015). From social networks to health: Durkheim after the turn of the millennium. Introduction. Social Science & Medicine,, 125, 1–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. , Chudzicka‐Czupała, A. , Grabowski, D. , Pan, R. , Adamus, K. , Wan, X. , Hetnal, M. , Tan, Y. , Olszewska‐Guizzo, A. , Xu, L. , McIntyre, R. S. , Quek, J. , Ho, R. , & Ho, C. (2020). The association between physical and mental health and face mask use during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A comparison of two countries with different views and practices. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 569981. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. , Pan, R. , Wan, X. , Tan, Y. , Xu, L. , McIntyre, R. S. , Choo, F. N. , Tran, B. , Ho, R. , Sharma, V. K. , & Ho, C. (2020). A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID‐19 epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 40–48. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, M. F. , Bacigalupe, G. , Daneshpour, M. , Han, W. J. , & Parra‐Cardona, R. (2020). COVID‐19 interconnectedness: Health inequity, the climate crisis, and collective trauma. Family Process, 59(3), 832–846. 10.1111/famp.12572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willen, S. S. , Knipper, M. , Abadía‐Barrero, C. E. , & Davidovitch, N. (2017). Syndemic vulnerability and the right to health. The Lancet, 389(10072), 964–977. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30261-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenham, C. , Smith, J. , Morgan, R. , & Gender and COVID‐19 Working Group . (2020). COVID‐19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak. The Lancet, 395(10227), 846–848. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30526-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong, E. (2020). Long‐haulers are redefining COVID‐19. Without understanding the lingering illness that some patients experience, we can't understand the pandemic. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/08/long-haulers-covid-19-recognition-support-groups-symptoms/615382/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of the qualitative research in this study, participants did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available. However, quantitative analysis results may be available by contacting Dr. Mana at manna.adi@gmail.com.