Abstract

Pregnant women and mothers who use substances often face significant barriers to accessing and engaging with substance use services. A scoping review was conducted in 2019 to understand how stigma impacts access to, retention in and outcomes of harm reduction and child welfare services for pregnant women and mothers who use substances. The forty‐two (n = 42) articles were analysed using the Action Framework for Building an Inclusive Health System developed by Canada's Chief Public Health Officer to articulate the ways in which stigma and related health system barriers are experienced at the individual, interpersonal, institutional and population levels. Many articles highlighted barriers across multiple levels, 19 of which cited barriers at the individual level (i.e., fear and mistrust of child welfare services), 18 at the interpersonal level (i.e., familial and relational influence on accessing substance use treatment), 30 at the institutional level (i.e., high organisational expectations on women) and 17 at the population level (i.e., negative stereotypes and racism). Our findings highlight the interconnectedness of stigma and related barriers and the ways in which stigma at the institutional and population levels pervasively influence individual and interpersonal experiences of stigma. Despite a wealth of literature on barriers to treatment and support for pregnant women and mothers who use substances, there has been minimal focus on how systems can address these formidable barriers. This review highlights the ways in which the barriers are connected and identifies opportunities for service providers and policymakers to better support pregnant women and mothers who use substances.

Keywords: harm reduction, parenting, pregnancy, stigma, substance use, women

What is known about this topic?

Pregnant women and mothers who use substances face unique stigma and formidable barriers to support, for both reducing harms associated with their substance use and enhancing their capacity to parent.

The Action Framework for Building an Inclusive Health System presents an understanding of multiple levels of stigma and solutions to address stigma at these levels.

Stigma is multifaceted and interrelated; stigma at the institutional and population levels systematically influences stigma and barriers at the individual and interpersonal levels.

What this paper adds?

An understanding of how multiple levels of stigma perpetuate barriers faced by pregnant women and mothers involved in substance use and child welfare services.

Evidenced‐based solutions for addressing these barriers are presented.

1. INTRODUCTION

Among pregnant women who use opioids, early and consistent access to prenatal care and harm reduction services, including opioid agonist treatment (OAT), is associated with fewer pregnancy complications and better foetal outcomes (Guan et al., 2019). However, pregnant women often face significant barriers to accessing services and in feeling safe to disclose substance use to service providers (Baskin et al., 2015; Carlson et al., 2006, 2008; Howard, 2015). Many of these barriers are influenced by the pervasive stigmatisation they experience (Bessant, 2003; Howell & Chasnoff, 1999). This is particularly true for Indigenous women, women of colour and women with lower socio‐economic status (Harvey et al., 2015; Howard, 2015; Stengel, 2014).

Stigma is a social construct whereby an individual or group of individuals is viewed negatively or discredited through damaging attitudes, behaviours and stereotypes that are based on a particular characteristic, such as drug use (Goffman, 1986). The concept of stigma is relational and contributes to inequalities in social and health outcomes at multiple interconnected levels (Goffman, 1986; Gunn & Canada, 2015; Stone, 2015; Tam, 2019). In 2019, the Canadian Chief Public Health Officer released the report Addressing Stigma: Towards a More Inclusive Health System, which draws attention to the connection between stigma, discrimination and poorer health outcomes among groups of people in Canada. The report includes the Stigma Pathways to Health Outcomes Model to conceptualize how stigma relates to health inequities at the individual, interpersonal, institutional and population levels (Tam, 2019). This model is accompanied by the Action Framework for Building an Inclusive Health System (Action Framework) that identifies how stigma can be addressed at the multiple interrelated levels, with the ultimate goal of finding solutions and interventions that result in better health outcomes (Tam, 2019).

The individual level of stigma encompasses how a person experiences stigma in their day‐to‐day life. This includes how individuals experience treatment, internalized feelings of shame, guilt, or blame and anticipated stigma which can result in individuals avoiding accessing treatment due to the fear of being stigmatised when attempting to access support services (Tam, 2019). The interpersonal level of stigma underlines how relationships and interactions, such as those with family, friends and service providers can be stigmatising. This level largely focuses on communication, such as the language used when interacting with someone who is experiencing substance misuse. This can include derogatory terms, intrusive questions or blaming individuals for their health‐related concerns (Tam, 2019). The institutional level is stigma within systems such as social services, medical centres or community organisations and can include institutional policies that cause harm or create barriers to access, such as non‐inclusive environments and inaccessible locations (Tam, 2019). Stigma at the population level is influenced by, and reflected in, societal values and norms (Tam, 2019). These norms influence discriminatory and exclusionary policies, internal procedures at the institutional level, within interpersonal relationships, and are often internalized by those who have been stigmatised, which can impact people's sense of self‐worth (Goffman, 1986; Tam, 2019).

For pregnant women and mothers who use opioids, these interrelated levels of stigma influence their access and engagement with health and social services. Stigma is often reflected in the attitudes and beliefs of care providers (Fonti et al., 2016; Tam, 2019), which can lead to health and social service providers taking punitive approaches to working with women, including increased surveillance and strict requirements to comply with care plans that are not collaboratively developed (Harvey et al., 2015; Howard, 2015; Stengel, 2014). Women often perceive that others, including their family members and service providers, hold negative thoughts about them. Women take on this stigma and incorporate negative stereotypes into their self‐concept (Gueta & Addad, 2013; Harvey et al., 2015; Howard, 2015). In turn, this self‐stigma leads to self‐consciousness, guilt and self‐blame and affects their confidence in their ability to parent (Harvey et al., 2015; Howard, 2015; Kenny & Barrington, 2018; Stengel, 2014).

This scoping review was conducted to (a) understand how the intersecting levels of stigma relate to pregnant women and new mothers who use substances, (b) identify how stigma and related barriers impact access to, retention in and outcomes of harm reduction programmes and interaction with child welfare services, and (c) propose how current responses to pregnant women and new mothers might be improved through stigma reduction efforts. While previous reviews have been undertaken in the child welfare (Carlson, 2006; Sun, 2000) and substance use (Carter, 2002; Raynor, 2013) fields that explore the role of stigma and related barriers for pregnant and parenting women who use substances, there has been minimal work that has explored the interconnections across fields and opportunities for collaborative action. This review was conducted as part of a larger project on stigma, pregnancy, parenting, child welfare and opioid use. The aim of the larger project was to identify and highlight culturally safe, trauma‐informed, harm reduction‐oriented and participant‐driven approaches for the substance use field and the child welfare sector, with emphasis on collaboration between the two systems (Schmidt et al., 2019).

2. METHODS

We conducted a scoping review in April 2019 on stigma, pregnancy, parenting, child welfare and substance use, following the scoping review methodology presented by Arksey and O'Malley (2005) and further clarified by Levac et al. (2010). The scoping review was guided by the research question: How do stigma and other factors (e.g., policy) impact access to, retention in and outcomes of harm reduction programmes and interaction with child welfare services for pregnant women and mothers who use substances?

We searched electronic databases to identify relevant studies including: CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Social Work Abstracts, Women's Studies International, and Academic Search Premier. The search included studies published in English from January 1999 to April 2019 combining keywords related to (a) the stigma experienced by pregnant and mothering women who use substances, (b) harm reduction services for pregnant women and mothers who use opioids and (c) substance use and child welfare. The reference lists of highly relevant included papers were searched for additional sources, and key topic‐specific journals on harm reduction and child welfare were manually searched for relevant articles.

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included peer‐reviewed qualitative and quantitative journal articles that described how stigma, discrimination, policy or social‐demographic variables (e.g., race, housing status, poverty and disability) impacted women's access to, retention or outcomes in services for (a) opioid use (e.g., methadone, OAT and safe injection sites) or (b) substance use services or treatment, and/or (c) interactions with child welfare including reunification, termination of parental rights and rates of investigation. Papers were excluded if they focused on the impacts of opioids on infants and children, barriers experienced outside of the substance use and child welfare fields (i.e., employment and justice) and those that focussed on stigma of opioid use outside of the context of pregnancy, motherhood or parenthood.

2.2. Study selection and quality appraisal

Papers were first title screened by one author (RS) to remove papers that were apparent from the title to not provide information directly related to the research question. The remaining papers were then independently reviewed by one of two authors (LW or JS). Papers were included at this stage by abstract if it provided enough information to determine eligibility. If not, the full paper was downloaded and reviewed. In alignment with Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) scoping review methodology, inclusion and exclusion criteria were amended post hoc, resulting in the inclusion of papers that addressed pregnancy and motherhood more broadly rather than the solely including articles with pregnant women and new mothers. The authors met weekly, while paper screening took place and used an iterative team approach to select relevant studies.

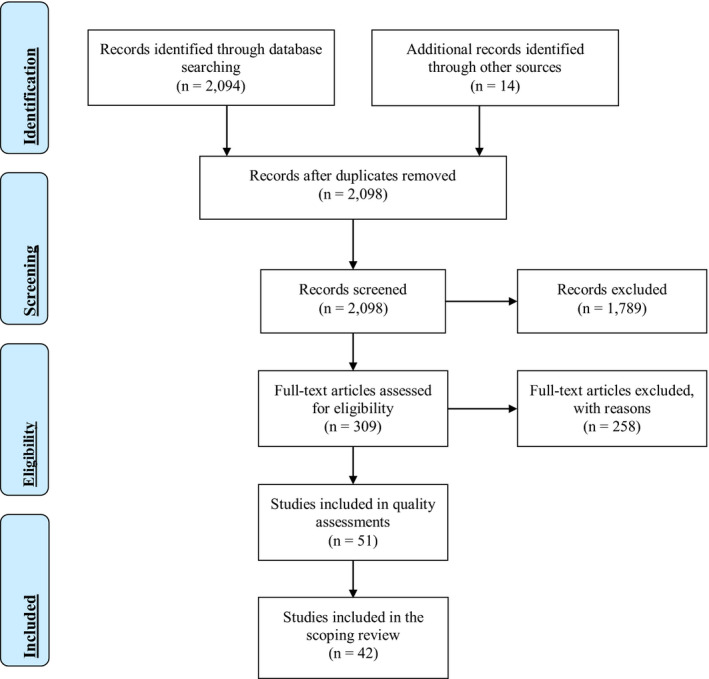

Fifty‐one (n = 51) articles were assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) 2018 Version, which is designed to facilitate the appraisal and inclusion of quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies within the same review (Hong et al., 2018). The four authors (JS/RS and LW/NP) each independently rated half of the included studies. The results of the MMAT were discussed as a team, and nine papers were excluded based on low‐quality rating. A flow diagram detailing the number of studies included and excluded at each stage is provided in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram adapted from Moher et al. (2009) for the scoping review process (Moher et al., 2009; Peters et al., 2015) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2.3. Study analysis

Information from the included papers (n = 42) was extracted independently by one of two authors (LW or JS) and charted in Excel. The extracted data was then collated and summarised to report the barriers and impacts on pregnant women and mothers' access to and retention or outcomes in services for opioid use or substance use services and treatment, on interactions with child welfare and across both services systems.

Each of the barriers identified during the data extraction process was then individually mapped and organised within the four levels (individual, interpersonal, institutional and population) articulated in the Action Framework (Tam, 2019) by one author (LW) and reviewed by the other three authors (JS, RS and NP) for consensus. Using the Action Framework to guide, the analysis offered an important opportunity to bridge literature using an individual behaviouralist approach with structural factors that have pervasive effects on individual and interpersonal behaviours and act as barriers to women's access to, retention in, and engagement with harm reduction and child welfare services while pregnant or parenting.

3. RESULTS

Our findings examined the types of barriers pregnant and mothering women involved in substance use and child welfare services experience at multiple levels. A comprehensive list of the barriers across the four levels of stigma can be found in Table 1. The majority of the studies were conducted in the US (n = 30), followed by Canada (n = 6), Australia (n = 2), United Kingdom (n = 3) and New Zealand (n = 1). The majority of included papers were qualitative (n = 23), followed by non‐randomised quantitative studies (n = 16) and mixed methods studies (n = 3).

TABLE 1.

Barriers across the stigma action framework

| Study included | ||

|---|---|---|

| Individual level of stigma—person who experiences individual stigma (i.e., unfair treatment, internalized stigma and anticipated stigma that inhibits accessing support) | Fear or mistrust of the child welfare system | Baskin et al. (2015); Blakey and Hatcher (2013); Carlson et al. (2006); Elms et al. (2018); Falletta et al. (2018); Howell and Chasnoff (1999); Jessup et al. (2003); Kruk and Banga (2011); Radcliffe (2009); Roberts and Nuru‐Jeter (2012); Rockhill et al. (2008); Taylor and Kroll (2004) |

| Internalized stigma (limiting self‐esteem/capacity to seek support) | Blakey and Hatcher (2013); Carlson et al. (2006); Elms et al. (2018); Feder et al. (2018); Radcliffe (2009); Rockhill et al. (2008); Salmon et al. (2000); Smith (2006); Stringer and Baker (2018) | |

| Fear of failing to reduce substance use | Elms et al. (2018); Jessup et al. (2003); Kruk and Banga (2011); Radcliffe (2009); Rockhill et al. (2008); Salmon et al. (2000) | |

| Trauma history | Carlson et al. (2008); Kenny and Barrington (2018) | |

| Previous substance use treatment attempts | Green et al. (2006) | |

| Fear of prenatal care | Jessup et al. (2003) | |

| Fear of prosecution due to substance use | Bessant (2003); Jessup et al. (2003) | |

| Interpersonal level of stigma—from friends, family, service providers, social/work networks (i.e., derogatory language, intrusive questions and hate crimes) | Partner's/family influence on treatment access | Bessant (2003); Carlson et al. (2006); Comfort and Kaltenbach (2000); Howell and Chasnoff (1999); Jessup et al. (2003); Rockhill et al. (2008); Tuten et al. (2003) |

| Stigma (substance use, mothering, pregnancy) | Bessant (2003); Carlson et al. (2006); Elms et al. (2018); Feder et al. (2018); Kenny and Barrington (2018); Radcliffe (2009); Rockhill et al. (2008); Stringer and Baker (2018) | |

| Having to restore trust and rebuilding relationships with children | Carlson et al. (2008); Kenny and Barrington (2018) | |

| Belief from providers that substance use results in an inability to parent | Drabble (2007); He et al. (2014) | |

| Lack of trusting and respectful relationships with service providers | Grosenick and Hatmaker (2000); Salmon et al. (2000) | |

| External expressions of trauma | Blakey and Hatcher (2013) | |

| Institutional level of stigma—organizational (i.e., being made to feel less than, longer wait times, non‐inclusive physical environment and institutional policies that cause harm) | Lack of coordination across service providers | Drabble (2007); Falletta et al. (2018); Haller et al. (2003); Henry et al. (2018); Howell and Chasnoff (1999); Kovalesky (2001); Lussier et al. (2010); Marcenko et al. (2011); Roberts and Nuru‐Jeter (2012); Robertson and Haight (2012); Smith and Testa (2002); Smith (2006); Taylor and Kroll (2004) |

| High expectations placed on women who use substances to meet an unrealistic number of tasks (including administrative tasks) | Baskin et al. (2015); Carlson et al. (2006, 2008); Elms et al. (2018); Falletta et al. (2018); He et al. (2014); Jessup et al. (2003); Lewis (2004); Radcliffe (2009); Roberts and Nuru‐Jeter (2012); Rockhill et al. (2008); Smith (2002) | |

| Institutional stigma due to low socioeconomic status or interpersonal resources (i.e., housing and food) | Bessant (2003); Carlson et al. (2008); Comfort and Kaltenbach (2000); Henry et al. (2018); Lean et al. (2013); Lussier et al. (2010); Marcenko et al. (2011); Rockhill et al. (2008); Tuten et al. (2003) | |

| Institutional stigma due to pregnancy or mothering status | Bessant (2003); Falletta et al. (2018); Howell and Chasnoff (1999); Jessup et al. (2003); Kruk and Banga (2011); Radcliffe (2009); Smith (2002, 2006) | |

| Lack of outreach/ability to access harm reduction and treatment programs | Bessant (2003); Elms et al. (2018); Green et al. (2006); Howell and Chasnoff (1999); Kruk and Banga (2011); Rockhill et al. (2008) | |

| Lack of gender‐ and trauma‐informed programming | Bessant (2003); Grosenick and Hatmaker (2000); Kruk and Banga (2011); Lewis (2004); Tuten et al. (2003) | |

| Geographic and transportation barriers to visitation (particularly in relation to substance use treatment programs) | Kovalesky (2001); Letourneau et al. (2013); Marcenko et al. (2011); Smith and Testa (2002) | |

| Impact of child welfare system (e.g. distracting mothers from reducing their substance use or increased substance use after apprehension) | Carlson et al. (2008); Jessup et al. (2003); Rockhill et al. (2015, 2008); Smith and Testa (2002); Smith (2002) | |

| Proof of treatment completion and abstinence from substances | Carlson et al. (2006); He et al. (2014); Robertson and Haight (2012); Taplin and Mattick (2015) | |

| Reunification timelines (mothers' readiness for reunification in relation to how long a child can be in foster care before parental rates are terminated) | Carlson (2006); Carlson et al. (2008); Kenny and Barrington (2018) | |

| Lack of financial support for programs (including allied services) | Carlson et al. (2006); Robertson and Haight (2012); Taylor and Kroll (2004) | |

| Wait times to access substance use services | Green et al. (2006); Kruk and Banga (2011); Rockhill et al. (2008) | |

| Lack of family‐centred programming | Carlson (2006); Kruk and Banga (2011) | |

| Lack of control over visitation rights and schedule | Kovalesky (2001); Smith and Testa (2002); Smith (2002) | |

| Lack of information sharing (with women and across staff) | Letourneau et al. (2013); Salmon et al. (2000) | |

| Staff turnover | Kruk and Banga (2011); Taylor and Kroll (2004) | |

| Insurance acceptability | Angelotta et al. (2016) | |

| Different perceptions of the impact of substance use across fields | Drabble (2007) | |

| Institutional barriers due to use of methadone maintenance | Lean et al. (2013) | |

| Population level of stigma—mass media, policies, law (i.e., stereotypes, negative portrayals in media, discriminatory policies and laws and inadequate legal protections) | Discrimination due to mental health status | Brown et al. (2016); Carlson et al. (2008); Henry et al. (2018); Lean et al. (2013); Marcenko et al. (2011); Marshall et al. (2011); Smith and Testa (2002) |

| Discrimination due to substance use | Baskin et al. (2015); Carlson et al. (2006); Kenny and Barrington (2018); Smith (2002); Taylor and Kroll (2004) | |

| Punitive approaches, including prenatal child welfare laws and apprehensions at birth | Angelotta et al. (2016); He et al. (2014); Roberts and Nuru‐Jeter (2012); Robertson and Haight (2012) | |

| Discrimination due to intergenerational involvement with child welfare | Blakey and Hatcher (2013); Marshall et al. (2011) | |

| Racism | Blakey and Hatcher (2013) | |

| Historical trauma | Baskin et al. (2015) | |

3.1. Individual experiences of stigma are expressed as fear and mistrust

Nineteen articles explored factors at the individual level of stigma, including fear and mistrust of the child welfare, health, and justice systems; internalized stigma; and concern related to not being able to reduce substance use. Fear or mistrust of child welfare (Baskin et al., 2015; Blakey & Hatcher, 2013; Carlson et al., 2006; Elms et al., 2018; Falletta et al., 2018; Howell & Chasnoff, 1999; Jessup et al., 2003; Kruk & Banga, 2011; Radcliffe, 2009; Roberts & Nuru‐Jeter, 2012; Rockhill et al., 2008; Taylor & Kroll, 2004), health (Jessup et al., 2003) and criminal justice (Bessant, 2003; Jessup et al., 2003) systems were the most frequently cited factors at the individual level. Fear and mistrust significantly impacted how women experienced substance use treatment, health and social services and many women avoided services because they anticipated being stigmatised.

Fear and mistrust of the child welfare system notably impacted women's access to harm reduction and social services (Blakey & Hatcher, 2013; Falletta et al., 2018). Some women feared that their child(ren) would be removed from their care and others worried that they did not know when they would be able to regain custody of their child(ren) (Baskin et al., 2015; Elms et al., 2018; Falletta et al., 2018; Howell & Chasnoff, 1999; Radcliffe, 2009; Rockhill et al., 2008; Salmon et al., 2000). Many of these fears were prompted by institutional and population level factors, including discriminatory laws and policies (Bessant, 2003; Carlson, 2006; Carlson et al., 2008; He et al., 2014; Jessup et al., 2003; Kenny & Barrington, 2018). At the individual level, these factors heightened internalized stigma, maternal guilt, shame and beliefs that women had ‘failed’ or were ‘unfit’ to mother (Carlson et al., 2006; Kenny & Barrington, 2018; Kruk & Banga, 2011; Smith, 2006). Internalized stigma also impacted women's confidence in their ability to parent (Carlson et al., 2008; Kenny & Barrington, 2018).

The stigma and fear of these systems prevented women from seeking services that they needed, such as prenatal care and counselling, and accessing services that could have benefited their health and pregnancy (Blakey & Hatcher, 2013; Kenny & Barrington, 2018; Stengel, 2014). Fear of child removal hindered women's ability to seek support and assistance and further resulted in women concealing their substance use and isolating, even if they wanted or needed support (Kenny & Barrington, 2018; Kruk & Banga, 2011). Reluctance to attend services was amplified where women had intergenerational involvement with the child welfare system and among women with histories of traumatic experiences (Baskin et al., 2015; Blakey & Hatcher, 2013; Marshall et al., 2011). In a Canadian study exploring women's social relationships and the quality support they received following child removal, Kenny and Barrington (2018) found that social isolation and stigma following child removal resulted in increased isolation, risk of intimate partner violence and increased substance use as a means of coping.

3.2. Interpersonal expressions of stigma are shaped by intimate relationships and service providers

Eighteen articles explored factors at the interpersonal level of stigma, including partners' and family's influence on women's treatment access, relationships with service providers and relationships with children. Similar to the individual level, many of the factors at the interpersonal level were influenced by factors at the institutional and population levels.

At the familial level, partner violence, partner's substance use, and lack of family and partner support were commonly cited as barriers for pregnant women and mothers to accessing substance use services (Bessant, 2003; Comfort & Kaltenbach, 2000; Howell & Chasnoff, 1999; Rockhill et al., 2008; Tuten et al., 2003). The absence of external support further perpetuated self‐stigma, fears of societal shame (Baskin et al., 2015), and being ostracised as a result of one's substance use (Kenny & Barrington, 2018). Several women cited heightened pressure to ‘perform’ as a good mother (Kenny & Barrington, 2018) and restore relationships with children who had been previously removed from their care within a mandated timeline (Carlson et al., 2008; Kenny & Barrington, 2018). While this barrier is perpetuated at an institutional or policy level, it impacted how mothers built or maintained meaningful relationships with their children.

Several articles cited women's relationships with service providers as a critical influence on experiences of interpersonal stigma. Radcliffe (2009) described women feeling judged for acknowledging the need to access substance use treatment, and that when women engaged with child welfare services, the topic of substance use dominated discussions (Radcliffe, 2009). Where women were able to access child welfare services, they expressed a lack of confidence from social workers with their ability to remain abstinent (Kenny & Barrington, 2018) or to parent (Kruk & Banga, 2011). These interactions limited information sharing between women and service providers, contributing to a lack of trusting and respectful relationships (Grosenick & Hatmaker, 2000; Letourneau et al., 2013; Salmon et al., 2000).

In an outpatient substance use treatment programe, Salmon et al. (2000) found that only 45% of pregnant women felt physicians/nurse practitioners provided adequate medical support and the majority of women felt providers did not give substantive information on substance use in pregnancy or when parenting. This could be in part due to discrimination related to pregnancy/mothering and substance use or the lack of tailored services for pregnant women and mothers in substance use treatment and harm reduction programmes (Elms et al., 2018; Howell & Chasnoff, 1999; Jessup et al., 2003; Radcliffe, 2009). Fewer women access treatment compared to men, and parents with children are less able to access harm reduction services or treatment compared to those without children (Feder et al., 2018; Stringer & Baker, 2018). Though this could be reflective of institutional and population levels factors, the identifiable gender differences in how women access harm reduction services or treatment can be reinforced on an interpersonal level.

3.3. Institutional stigma strongly affects access to substance use and parenting supports

Thirty articles discussed the barriers at the institutional level, including stigma enacted within health systems, in health and social service training programmes, and health and social service organisations. Barriers at the institutional level were formidable and they emerged in pervasive ways to the individual and interpersonal levels. Stigma at the institutional level impacted women directly (i.e., organisational expectations on women; Baskin et al., 2015; Carlson et al., 2006, 2008; Drabble, 2007; Elms et al., 2018; Falletta et al., 2018; He et al., 2014; Jessup et al., 2003; Lewis, 2004; Radcliffe, 2009; Roberts & Nuru‐Jeter, 2012; Rockhill et al., 2008; Smith, 2002) and indirectly (i.e., lack of coordination across service providers; Drabble, 2007; Falletta et al., 2018; Henry et al., 2018; Kovalesky, 2001; Lussier et al., 2010; Marcenko et al., 2011; Robertson & Haight, 2012; Smith & Testa, 2002; Smith, 2006; Taylor & Kroll, 2004). Institutional stigma was heightened for women with comorbid substance use and mental health issues, and for women with lower income who often had limited resources such as housing, food and employment (Bessant, 2003; Carlson et al., 2008; Comfort & Kaltenbach, 2000; Henry et al., 2018; Lean et al., 2013; Lussier et al., 2010; Marcenko et al., 2011; Rockhill et al., 2008; Tuten et al., 2003).

Within the child welfare system, a number of articles described how women had high expectations placed on them to complete an unrealistic number of tasks and extensive documentation including proof of substance use treatment completion, employment and housing (Falletta et al., 2018; Marcenko et al., 2011; Smith, 2002; Taplin & Mattick, 2015). Meeting these demands was found to be particularly difficult for women with mental health comorbidities or intergenerational involvement in child welfare services and who were less likely to be reunified with their children compared to families without previous child welfare involvement (Marshall et al., 2011). This may be correlated with a lack of training on substance use within the child welfare field or a result of limited coordination across providers to deliver comprehensive mental health, substance use and social services (Falletta et al., 2018).

Within the substance use field, pregnancy and mothering status largely impacted women's access to and retention in harm reduction programmes. Substance use treatment is often not gender informed or family oriented, and there is limited programming that addresses the specific and diverse needs of pregnant women and mothers (Bessant, 2003; Falletta et al., 2018; Howell & Chasnoff, 1999; Jessup et al., 2003; Kruk & Banga, 2011; Radcliffe, 2009; Smith, 2002; Smith, 2006). For example, programmes may not accept mothers with young children or provide child minding, which both limits women's access to harm reduction programmes and women's ability to stay in the programme for the full length of time (Carlson, 2006; Kruk & Banga, 2011).

Women also experienced challenges in knowing how to access substance use services due to a lack of outreach, or information available about the services. The lack of information available to pregnant and mothering women further contributed to women's concerns that their substance use will be reported to child welfare services or the criminal justice system (Bessant, 2003; Jessup et al., 2003). Homelessness further exacerbated these barriers due to a greater disconnect to information, increased violence and substance use, and overall lack of socioeconomic support associated with the lack of housing (Bessant, 2003).

Where women were able to obtain information about substance use services, waitlists acted as additional barriers to women accessing treatment (Elms et al., 2018; Rockhill et al., 2008). Moreover, many substance use and harm reduction programmes identified in the review were privately owned and located in large cities. Often these programmes did not accept insurance, requiring women to pay upfront in cash (Jessup et al., 2003; Rockhill et al., 2008). The location and cost of these programmes heightened geographic and transportation barriers, particularly for women in rural and remote regions or whose children were in foster care in other regions (Howell & Chasnoff, 1999; Jessup et al., 2003; Letourneau et al., 2013). For women using OAT, such as methadone that requires daily access to a pharmacy, women's geographic location and transportation access posed increased challenges (Lander et al., 2013).

Underlying a number of the barriers at the institutional level is the differing mandates and paradigms between the substance use and child welfare fields, and the resulting lack of coordination across providers. Within the substance use literature, abstinence‐based policies also generated fears of child removal and ultimately deterred women from seeking services (Carlson, 2006; He et al., 2014; Robertson & Haight, 2012; Taplin & Mattick, 2015). Moreover, longer term needs requiring coordinated efforts, such as stable housing and access to mental health services were often not met even where the immediate substance use‐related needs of women were addressed (Haller et al., 2003; Howell & Chasnoff, 1999). The lack of coordination and collaboration among health and social services was evident in a lack of cross‐training (Falletta et al., 2018; Smith & Testa, 2002; Smith, 2006), inconsistent referrals and service delivery (Lussier et al., 2010; Robertson & Haight, 2012; Taylor & Kroll, 2004), and different perceptions of the impacts of substance use across fields (Drabble, 2007).

3.4. The operationalization of stigma at the population level

Seventeen articles cited barriers at the population level. These barriers are related to discriminatory and exclusionary policies and procedures at the institutional level, within interpersonal relationships, and are often internalized to influence people's sense of self‐worth (Goffman, 1986; Tam, 2019). Stigma, discrimination and judgement were the most commonly cited barriers to accessing child welfare and substance use services.

In the literature, many of the population level barriers were cited within the context of how they manifested at the individual, interpersonal and institutional levels. For example, in a study on women's social support following child removal, stigma was described as a ‘pervasive force’ that reinforced ‘social blame and isolation’ (Kenny & Barrington, 2018, p. 211). Some of the women participating in the study described ongoing fear of social exposure and shaming, as well as the ‘desire to keep this part of her life secret’ or ‘avoid[ing] the anticipated shame and judgement [child removal] would invariably report’ (Kenny & Barrington, 2018, p. 213). Another study noted that women were ‘branded’ as uncaring or abusive as a result of substance use, which impacted how women were able to engage with child welfare services (Baskin et al., 2015). Studies that described negative stereotypes and societal shame related to substance use during pregnancy (Baskin et al., 2015; Carlson et al., 2006; Kenny & Barrington, 2018; Smith, 2002; Taylor & Kroll, 2004) and mental health challenges (Brown et al., 2016; Carlson et al., 2008; Henry et al., 2018; Lean et al., 2013; Marcenko et al., 2011; Marshall et al., 2011; Smith & Testa, 2002) highlighted the impacts of the shame rather than the norms and stereotypes themselves.

Several discriminatory laws and policies were described in the literature. Policies that dictate the length of time that a child could be placed in foster care before parental rights are terminated (Carlson, 2006; Carlson et al., 2008; He et al., 2014; Kenny & Barrington, 2018) or where non‐compliance results in jail time (He et al., 2014) have lasting impacts on women's self‐efficacy (Brown et al., 2016; Kenny & Barrington, 2018), confidence in their ability to parent (Carlson et al., 2008; Kenny & Barrington, 2018), and their willingness to seek support. Colonial policies further reinforced historical and intergenerational trauma, which were found to lead to multigenerational involvement with, and mistrust of, the child welfare system (Baskin et al., 2015). Moreover, while racism was less frequently cited, in a study of Black mothers' experiences with regaining custody of their children, Blakey and Hatcher (2013) reported that intergenerational racism, classism and sexism magnified discrimination.

4. DISCUSSION

This review describes significant and interrelated barriers pregnant women and mothers who use substances face when accessing and engaging with substance use services. For over 20 years, the academic literature has identified barriers to treatment and support for pregnant women and mothers who use substances. However, these barriers for women have persisted as systems have generally remained resistant to change and continue to work in silos (Urbanoski et al., 2018). In this discussion, the barriers associated with the four levels of stigma identified in the Action Framework are summarised and linked to examples, identified through the larger project on stigma, pregnancy, parenting, child welfare and opioid use (Schmidt et al., 2019), of emergent strategies from the substance use and child welfare fields to overcome these barriers.

4.1. Group‐based programming

At the individual level, group‐based programmes and supports can reduce internalized stigma and improve the well‐being of individuals by strengthening coping skills, building social support and increasing self‐efficacy (Brown et al., 2016; Tam, 2019). In support groups, women are encouraged to share information in a safe environment and build networks inclusive of others who are also working to reduce their substance use (Rutman & Hubberstey, 2019). For pregnant women and mothers who use opioids, group‐based supports can provide a safe space to collectively recognise and address issues such as substance use and experiences of violence. Within these supportive settings, women can determine their goals, needs and steps required to address their substance use without judgement and identify and practice new skills (Carlson, 2006; Carter, 2002; Lewis, 2004). Group‐based programmes in harm reduction and substance use treatment settings can cover a range of topics, from substance use reduction to attachment‐based parenting. Parenting programming in harm reduction services and substance use treatment can foster the development of stronger communication and problem‐solving skills; build relationships between children, parents and providers; and support identification and practice of positive coping strategies (Akin, Brook, et al., 2018; Akin, Johnson‐Motoyama, et al., 2018). Women accessing substance use services have expressed being more comfortable discussing their substance use and interrelated issues when organisations offer peer support programming. Rockhill et al. (2015) found that in a parent‐directed peer mentorship programme for parents with substance use concerns who were engaged in the child welfare system, participants were able to build caring relationships, self‐efficacy and motivation to access services.

Group‐based programmes can also promote improvement in interpersonal relationships, such as those between women and providers. For example, The Strengthening Families Program is an evidence‐based 14‐week parenting programme for families involved with child welfare that was developed in the 1980s. The programme includes groups for children and parents as well as time for supervised practice of newly developed skills (Akin, Brook, et al., 2018). Recent evaluations of the programme have found that developing relationships between parents and providers throughout the programme resulted in increased parental engagement in the group, reduced substance use, fewer days where children were placed in out‐of‐home care, and increased family and parental functioning (Akin, Johnson‐Motoyama, et al., 2018; Brook et al., 2016).

4.2. Training and education

Service provider education and training can target stigma at the interpersonal level. Interventions that encourage providers to examine their personal values, beliefs and biases about women who use opioids can result in a better understanding of women's experiences and perspectives (Tam, 2019). For example, Seybold et al. (2014) describe a multidisciplinary workshop conducted with a wide range of health and social service providers including nurses, social workers and physicians. The workshop was designed to increase understanding of addiction, substance use treatment and professional readiness to support pregnant individuals who use substances. In the workshop evaluation survey, service providers reported they increased their compassion to pregnant patients who use substances (Seybold et al., 2014). Training and education that includes both child welfare and substance use service providers can increase shared understanding and skill sets, help improve the understanding of the other sector's role, increase communication and referrals, and promote successful collaborations between substance use and child welfare systems that support changes to practice that reduce barriers (Schmidt et al., 2019; Seybold et al., 2014).

4.3. Trauma‐, gender‐ and culture‐informed practice

Proactive efforts to address stigma at the institutional level are interconnected with individual and interpersonal dynamics. At this level, stigma‐reducing approaches can include ongoing training and education, creating safe and inclusive work environments, engaging in institutional and cross‐sectoral collaboration, and the implementation of trauma/violence‐, culture‐ and gender‐informed approaches (Tam, 2019). Embedding these approaches into programme philosophies can support service providers to work in non‐judgemental and compassionate ways, which is critically important to providing safe care to pregnant women and mothers (Hubberstey et al., 2019).

Service providers who understand the impact that experiences of trauma and violence have on women's substance use are more likely to create physical, psychological and emotional safety for women (Blakey & Hatcher, 2013). Culturally‐informed practice and those that address intergenerational trauma can reduce power imbalances between women and providers, facilitate trust and healing, and support self‐determination (Carter, 2002; Hines, 2013). For example, Manito Ikwe Kagikwe (The Mothering Project), a holistic harm reduction programme in Canada, integrates culture into all of its programming. Women are invited to participate in events related to their culture, such as baby naming, smudging and drumming. Having a wide array of culture‐informed programming has supported women in meeting their diverse needs (Wolfson et al., 2019).

The provision of gender‐informed and gender‐specific services that account for the unique service needs of women has also been found to reduce barriers for pregnant women and mothers. In a study by Grosenick and Hatmaker (2000), women in substance use treatment described feeling safer and less pressure to be performative around staff who are women, compared to men (Grosenick & Hatmaker, 2000).

4.4. Collaborative care models and cross‐section collaboration

Promising approaches to service delivery that can address stigma and enhance collaboration include family‐centred substance use treatment, cross‐agency collaboration, co‐located services, and case management. Often embedded within these models are the values of collaboration, mother–child togetherness and holism (Howell & Chasnoff, 1999; Robertson & Haight, 2012; Schmidt et al., 2019). Family‐centred treatment programmes provide services to different members of the family and have the potential to make programmes more accessible for women (Kruk & Banga, 2011). Family‐centred programmes address frequently cited barriers such as lack of childcare, fear of child removal and transportation to substance use treatment by allowing children to live with their parents in facilities (Baskin et al., 2015). Integrated treatment for mothers and their children has positive impacts on maternal substance use, maternal mental health, and birth outcomes, as well as enhanced parenting capacity and confidence, and decreased rates of children in care (Clark, 2001; Sword et al., 2009). Women who participate in integrated treatment are better able to focus on their own recovery and thus have higher completion rates and longer stays (Clark, 2001). For example, in an evaluation of 24 live‐in treatment services in the United States, postpartum women with their infants had the highest rates of completion (48%) and longest treatment stays (192 days), whereas postpartum women without their children had the lowest rates of completion (17%) and shortest treatment stays (76 days; Clark, 2001).

Cross‐agency collaboration can facilitate increased support services for women due to a more holistic understanding of the factors that contribute to women's substance use and child welfare engagement (Drabble, 2007; Howell & Chasnoff, 1999). Collaboration between services, including those outside the substance use and child welfare sectors, creates an environment dedicated to addressing a wide range of personal, social, material and health needs (Comfort & Kaltenbach, 2000). Case management models link women to services they need, including those to support harm reduction, and can be provided in a variety of environments, such as at home, in community services, or during substance use treatment (Olsen et al., 2015). Collaborative models where child welfare and substance use service providers work as a team, or in the same location, can lead to higher referrals to and receipt of substance use services among child welfare clients (He, 2017). These models can also result in increased attainment of treatment goals, maintained custody and greater reunification if custody is lost (Huebner et al., 2015, 2018; Rockhill et al., 2008).

4.5. Evidence‐based policy development

Institutional interventions, such as cross‐system collaboration and the integration of trauma/violence‐, gender‐ and culture‐informed principles, can be reinforced through population‐level actions. Funding for collaborative care programmes, developing and implementing protective rather than punitive laws and policies and addressing discrimination within existing laws and policies can support stigma reduction at the institutional and interpersonal levels (Tam, 2019). Policies that address and integrate responses to social and structural factors that influence women's substance use such as poverty, colonization and intergenerational trauma, and lack of housing are necessary (Baskin et al., 2015; Bessant, 2003; Marcenko et al., 2011; Robertson & Haight, 2012). Collaborations across ministries or governmental departments can act as a crucial bridge for agency and partner collaboration to reduce the challenges associated with caring for women with complex needs (Meixner et al., 2016).

Addressing women's experiences of stigma and related barriers at the individual, interpersonal, institutional and population levels not only has beneficial outcomes for women but also their children, families and communities (Racine et al., 2009). Evidenced outcomes include improved physical and mental health, reduced substance use, improved child welfare outcomes (Carlson, 2006; Carlson et al., 2006, 2008; Comfort & Kaltenbach, 2000), positive parenting outcomes (Taplin & Mattick, 2015), safe housing (Drabble, 2007), and healthy relationships and support networks (Drabble, 2007; Elms et al., 2018).

4.6. Limitations

This scoping review was conducted to understand how stigma and related factors impact access to, retention in and outcomes of harm reduction programmes and child welfare engagement for pregnant women and mothers who use substances. While the results capture stigma and related barriers at the individual, interpersonal, and to an extent, the institutional levels, literature that captured barriers at the population level was limited. Future research should examine how discriminatory laws and policies shape women's experiences with accessing substance use treatment and child welfare services and how these policies could be improved to support women and in turn reduce stigma at all levels identified by the Action Framework. While there is an abundance of research on the barriers that women face, results from the scoping review demonstrate a limited amount of research on destigmatising interventions that address these barriers. Interventions to successfully address these barriers require further research. Finally, this scoping review was conducted as part of a project focused on opioids. While many of the results provided findings on substance use generally, future research may benefit from a more expansive search that includes other substances, including alcohol and tobacco, which have known effects on foetal growth and development.

5. CONCLUSION

Pregnant women and mothers who use substances face significant and persistent stigma and barriers in accessing and maintaining support to reduce harms associated with their substance use and enhance their capacity to parent. These barriers are rooted in systemic levels of stigma and discrimination that have foundations in racism, colonialism and sexism. These barriers have often been articulated, yet action to surmount them has been slow, and at times, stagnant. However, hopeful signs of change are beginning to emerge. In Canada, the release of the Action Framework articulates how stigma operates at multiple levels and impacts those who are most in need of services. Through understanding the nuances, drivers and experiences of multiple forms of stigma, service providers and policymakers may be better situated to identify effective and collaborative interventions. Shifts in the substance use field to embrace a public health approach offer new hope and ideas for addressing the discrimination and injustice faced by pregnant women and mothers who use substances. Concurrently, the importance of early attachment and the harms of separating mothers and children are prompting the child welfare field to rethink approaches and, in some cases, the specific need to support, rather than punish, mothers who use substances.

This review identified literature from the past two decades on the topic of stigma and barriers facing pregnant women and mothers who use substances who come into contact with the child welfare system. Using the Action Framework, we were able to address the barriers in a pragmatic way and describe emerging interventions to address stigma at four levels. These interventions are multilevel, allowing service providers and policymakers to identify and act on how stigma and barriers at the institutional and population levels permeate and influence barriers at the individual and interpersonal levels. In this and related work, we see the importance of utilizing principles for developing and advancing anti‐stigma interventions that promote harm reduction, recovery, and capacity to parent, in order to reach and engage pregnant women and mothers who use substances. In the studies cited in this review, we presented evidence of successful interventions that were guided by the principles of being traumainformed, culturally safe and women‐centred and that support mother–child togetherness. It is due time for collaborative action by the substance use and child welfare fields to enact these principles and approaches.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Wolfson L, Schmidt RA, Stinson J, Poole N. Examining barriers to harm reduction and child welfare services for pregnant women and mothers who use substances using a stigma action framework. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29:589–601. 10.1111/hsc.13335

Funding information

Financial assistance was provided by Health Canada, Substance Use and Addiction Program. The views herein do not necessarily represent those of Health Canada.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable – no new data generated.

REFERENCES

- Akin, B. A. , Brook, J. , Johnson‐Motoyama, M. , Paceley, M. , & Davis, S. (2018). Engaging substance‐affected families in child welfare: Parent perspectives of a parenting intervention at program initiation and completion. Journal of Family Social Work, 21(4/5), 313–330. 10.1080/10522158.2018.1469562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akin, B. A. , Johnson‐Motoyama, M. , Davis, S. , Paceley, M. , & Brook, J. (2018). Parent perspectives of engagement in the strengthening families program: An evidence‐based intervention for families in child welfare and affected by parental substance use. Child & Family Social Work, 23(4), 735–742. 10.1111/cfs.12470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angelotta, C. , Weiss, C. J. , Angelotta, J. W. , & Friedman, R. A. (2016). A moral or medical problem? The relationship between legal penalties and treatment practices for opioid use disorders in pregnant women. Women's Health Issues, 26(6), 595–601. 10.1016/j.whi.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H. , & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin, C. , Strike, C. , & McPherson, B. (2015). Long time overdue: An examination of the destructive impacts of policy and legislation on pregnant and parenting aboriginal women and their children. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 6(1), 1–19. 10.18584/iipj.2015.6.1.5 27867445 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bessant, J. (2003). Pregnancy in a Brotherhood bin: Housing and drug‐treatment options for pregnant young women. Australian Social Work, 56(3), 234–246. 10.1046/j.0312-407x.2003.00077.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blakey, J. M. , & Hatcher, S. S. (2013). Trauma and substance abuse among child welfare involved African American mothers: A case study. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 7(2), 194–216. 10.1080/15548732.2013.779623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brook, J. , Akin, B. A. , Lloyd, M. , Bhattarai, J. , & McDonald, T. P. (2016). The use of prospective versus retrospective pretests with child‐welfare involved families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(9), 2740–2752. 10.1007/s10826-016-0446-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. , Hicks, L. M. , & Tracy, E. M. (2016). Parenting efficacy and support in mothers with dual disorders in a substance abuse treatment program. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 12(3/4), 227–237. 10.1080/15504263.2016.1247998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, B. E. (2006). Best practices in the treatment of substance‐abusing women in the child welfare system. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 6(3), 97–115. 10.1300/J160v06n03_08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, B. E. , Matto, H. , Smith, C. A. , & Eversman, M. (2006). A pilot study of reunification following drug abuse treatment: Recovering the mother role. Journal of Drug Issues, 36(4), 877–902. 10.1177/002204260603600406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, B. E. , Smith, C. , Matto, H. , & Eversman, M. (2008). Reunification with children in the context of maternal recovery from drug abuse. Families in Society, 89(2), 253–263. 10.1606/1044-3894.3741 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, C. S. (2002). Prenatal care for women who are addicted: Implications for gender‐sensitive practice. Affilia, 17(3), 299–313.Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=106794685&site=ehost‐live&scope=site [Google Scholar]

- Clark, H. W. (2001). Residential substance abuse treatment for pregnant and postpartum women and their children: Treatment and policy implications. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program, 80(2), 179–198.Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2001‐00597‐004&site=ehost‐live&scope=site [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comfort, M. , & Kaltenbach, K. A. (2000). Predictors of treatment outcomes for substance‐abusing women: A retrospective study. Substance Abuse, 21(1), 33–45. 10.1080/08897070009511416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble, L. (2007). Pathways to collaboration: Exploring values and collaborative practice between child welfare and substance abuse treatment fields. Child Maltreatment, 12(1), 31–42. 10.1177/1077559506296721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elms, N. , Link, K. , Newman, A. , & Brogly, S. B. , House, K. (2018). Need for women‐centered treatment for substance use disorders: Results from focus group discussions. Harm Reduction Journal, 15(1), 40. 10.1186/s12954-018-0247-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falletta, L. , Hamilton, K. , Fischbein, R. , Aultman, J. , Kinney, B. , & Kenne, D. (2018). Perceptions of child protective services among pregnant or recently pregnant, opioid‐using women in substance abuse treatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 79, 125–135. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder, K. A. , Mojtabai, R. , Musci, R. J. , & Letourneau, E. J. (2018). U.S. adults with opioid use disorder living with children: Treatment use and barriers to care. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 93, 31–37. 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonti, S. , Davis, D. , & Ferguson, S. (2016). The attitudes of healthcare professionals towards women using illicit substances in pregnancy: A cross‐sectional study. Women and Birth, 29(4), 330–335. 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. (1986). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity (1st Touchstone ed.). Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Green, B. L. , Rockhill, A. , & Furrer, C. (2006). Understanding patterns of substance abuse treatment for women involved with child welfare: The influence of the Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA). The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 32(2), 149–176. 10.1080/00952990500479282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosenick, J. K. , & Hatmaker, C. M. (2000). Perceptions of staff attributes in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 19(3), 273–284. 10.1016/S0740-5472(00)00109-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Q. , Sproule, B. A. , Vigod, S. N. , Cadarette, S. M. , Greaves, S. , Martins, D. , & Gomes, T. (2019). Impact of timing of methadone initiation on perinatal outcomes following delivery among pregnant women on methadone maintenance therapy in Ontario: Impact of methadone use on perinatal outcomes. Addiction, 114(2), 268–277. 10.1111/add.14453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueta, K. , & Addad, M. (2013). Moulding an emancipatory discourse: How mothers recovering from addiction build their own discourse. Addiction Research & Theory, 21(1), 33–42. 10.3109/16066359.2012.680080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, A. J. , & Canada, K. E. (2015). Intra‐group stigma: Examining peer relationships among women in recovery for addictions. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 22(3), 281–292. 10.3109/09687637.2015.1021241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller, D. L. , Miles, D. R. , & Dawson, K. S. (2003). Factors influencing treatment enrollment by pregnant substance abusers. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 29(1), 117–131. 10.1081/ADA-120018842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, S. , Schmied, V. , Nicholls, D. , & Dahlen, H. (2015). Hope amidst judgement: The meaning mothers accessing opioid treatment programmes ascribe to interactions with health services in the perinatal period. Journal of Family Studies, 21(3), 282–304. 10.1080/13229400.2015.1110531 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He, A. S. (2017). Interagency collaboration and receipt of substance abuse treatment services for child welfare‐involved caregivers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 79, 20–28. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, A. S. , Traube, D. E. , & Young, N. K. (2014). Perceptions of parental substance use disorders in cross‐system collaboration among child welfare, alcohol and other drugs, and dependency court organizations. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(5), 939–951. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry, C. , Liner‐Jigamian, N. , Carnochan, S. , Taylor, S. , & Austin, M. J. (2018). Parental substance use: How child welfare workers make the case for court intervention. Children and Youth Services Review, 93, 69–78. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hines, L. (2013). The treatment views and recommendations of substance abusing women: A meta‐synthesis. Qualitative Social Work, 12(4), 473–489. 10.1177/1473325011432776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q. N. , Fàbregues, S. , Bartlett, G. , Boardman, F. , Cargo, M. , Dagenais, P. , Gagnon, M.‐P. , Griffiths, F. , Nicolau, B. , O’Cathain, A. , Rousseau, M.‐C. , Vedel, I. , & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. 10.3233/EFI-180221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, H. (2015). Reducing stigma: Lessons from opioid‐dependent women. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 15(4), 418–438. 10.1080/1533256X.2015.1091003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howell, E. M. , & Chasnoff, I. J. (1999). Perinatal substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 17(1–2), 139–148. 10.1016/S0740-5472(98)00069-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubberstey, C. , Rutman, D. , Schmidt, R. , van Bibber, M. , & Poole, N. (2019). Multi‐service programs for pregnant and parenting women with substance use concerns: Women’s perspectives on why they seek help and their significant changes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(8), 3299. 10.3390/ijerph16183299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner, R. A. , Hall, M. T. , Smead, E. , Willauer, T. , & Posze, L. (2018). Peer mentoring services, opportunities, and outcomes for child welfare families with substance use disorders. Children and Youth Services Review, 84, 239–246. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner, R. A. , Willauer, T. , Posze, L. , Hall, M. T. , & Oliver, J. (2015). Application of the evaluation framework for program improvement of START. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 9(1), 42–64. 10.1080/15548732.2014.983289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jessup, M. A. , Humphreys, J. C. , Brindis, C. D. , & Lee, K. A. (2003). Extrinsic barriers to substance abuse treatment among pregnant drug dependent women. Journal of Drug Issues, 33(2), 285–304. 10.1177/002204260303300202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, K. S. , & Barrington, C. (2018). 'People just don't look at you the same way': Public stigma, private suffering and unmet social support needs among mothers who use drugs in the aftermath of child removal. Children and Youth Services Review, 86, 209–216. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.01.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalesky, A. (2001). Factors affecting mother–child visiting identified by women with histories of substance abuse and child custody loss. Child Welfare, 80(6), 749–768.Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=5947648&site=ehost‐live&scope=site [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, E. , & Banga, P. S. (2011). Engagement of substance‐using pregnant women in addiction recovery. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 30(1), 79–91.Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=104662347&site=ehost‐live&scope=site [Google Scholar]

- Lander, L. R. , Marshalek, P. , Yitayew, M. , Ford, D. , Sullivan, C. R. , & Gurka, K. K. (2013). Rural healthcare disparities: Challenges and solutions for the pregnant opioid‐dependent population. The West Virginia Medical Journal, 109(4), 22–27.Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=23930558&site=ehost‐live&scope=site [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lean, R. E. , Pritchard, V. E. , & Woodward, L. J. (2013). Child protection and out‐of‐home placement experiences of preschool children born to mothers enrolled in methadone maintenance treatment during pregnancy. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(11), 1878–1885. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau, N. , Campbell, M. A. , Woodland, J. , & Colpitts, J. (2013). Supporting mothers’ engagement in a community‐based methadone treatment program. Nursing Research and Practice, 2013, 987463. 10.1155/2013/987463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D. , Colquhoun, H. , & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, L. M. (2004). Culturally appropriate substance abuse treatment for parenting African American women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 25(5), 451–472. 10.1080/01612840490443437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier, K. , Laventure, M. , & Bertrand, K. (2010). Parenting and maternal substance addiction: Factors affecting utilization of child protective services. Substance Use & Misuse, 45(10), 1572–1588. 10.3109/10826081003682123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcenko, M. O. , Lyons, S. J. , & Courtney, M. (2011). Mothers' experiences, resources and needs: The context for reunification. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(3), 431–438. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.06.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, J. M. , Huang, H. , & Ryan, J. P. (2011). Intergenerational families in child welfare: Assessing needs and estimating permanency. Children & Youth Services Review, 33(6), 1024–1030. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meixner, T. , Milligan, K. , Urbanoski, K. , & McShane, K. (2016). Conceptualizing integrated service delivery for pregnant and parenting women with addictions: Defining key factors and processes. Canadian Journal of Addiction, 7, 57–65. 10.1097/02024458-201609000-00008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , & Altman, D. J. ; The PRISMA Group . (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 6, e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, L. J. , Laprade, V. , & Holmes, W. M. (2015). Supports for families affected by substance abuse. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 9(5), 551–570. 10.1080/15548732.2015.1091761 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D. J. , Godfrey, C. M. , Khalil, H. , McInerney, P. , Parker, D. , & Baldini Soares, C. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence Based Healthcare, 13, 141–146. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine, N. , Motz, M. , Leslie, M. , & Pepler, D. (2009). Breaking the cycle pregnancy outreach program. Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering, 11(1), 279–290.Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=fyh&AN=43482444&site=ehost‐live&scope=site [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe, P. (2009). Drug use and motherhood: Strategies for managing identity. Drugs & Alcohol Today, 9(3), 17–21.Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=105323323&site=ehost‐live&scope=site [Google Scholar]

- Raynor, P. A. (2013). An exploration of the factors influencing parental self‐efficacy for parents recovering from substance use disorders using the social ecological framework. Journal of Addictions Nursing (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins), 24(2), 91–101. 10.1097/JAN.0b013e3182922069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. , & Nuru‐Jeter, A. (2012). Universal screening for alcohol and drug use and racial disparities in child protective services reporting. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 39(1), 3–16. 10.1007/s11414-011-9247-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, A. S. , & Haight, W. (2012). Engaging child welfare‐involved families impacted by substance misuse: Scottish policies and practices. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(10), 1992–2001. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.06.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rockhill, A. , Furrer, C. J. , & Duong, T. M. (2015). Peer mentoring in child welfare: A motivational framework. Child Welfare, 94(5), 125–144.Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=110870829&site=ehost‐live&scope=site [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockhill, A. , Green, B. L. , & Newton‐Curtis, L. (2008). Accessing substance abuse treatment: Issues for parents involved with child welfare services. Child Welfare, 87(3), 63–93.Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=35619175&site=ehost‐live&scope=site [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutman, D. , & Hubberstey, C. (2019). National evaluation of Canadian multi‐service FASD prevention programs: Interim findings from the Co‐Creating Evidence Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(10). 10.3390/ijerph16101767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon, M. M. , Joseph, B. M. , Saylor, C. , & Mann, R. J. (2000). Women's perception of provider, social, and program support in an outpatient drug treatment program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 19(3), 239–246. 10.1016/S0740-5472(00)00103-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R. , Wolfson, L. , Stinson, J. , Poole, N. , & Greaves, L. (2019). Mothering and opioids: Addressing stigma and acting collaboratively. Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health. https://bccewh.bc.ca/wp‐content/uploads/2019/11/CEWH‐01‐MO‐Toolkit‐WEB2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Seybold, D. , Calhoun, B. , Burgess, D. , Lewis, T. , Gilbert, K. , & Casto, A. (2014). Evaluation of a training to reduce provider bias toward pregnant patients with substance abuse. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 14(3), 239–249. 10.1080/1533256X.2014.933730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. D. , & Testa, M. F. (2002). The risk of subsequent maltreatment allegations in families with substance‐exposed infants. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26(1), 97–114. 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00307-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. (2002). Reunifying families affected by maternal substance abuse: Consumer and service provider perspectives on the obstacles and the need for change. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 2(1), 33–53.Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=106820752&site=ehost‐live&scope=site [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. A. (2006). Empowering the "Unfit" mother. Affilia, 21(4), 448–457. 10.1177/0886109906292110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stengel, C. (2014). The risk of being ‘too honest’: Drug use, stigma and pregnancy. Health, Risk & Society, 16(1), 36–50. 10.1080/13698575.2013.868408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stone, R. (2015). Pregnant women and substance use: Fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Health & Justice, 3(2), 1–15. 10.1186/s40352-015-0015-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, K. L. , & Baker, E. H. (2018). Stigma as a barrier to substance abuse treatment among those with unmet need: An analysis of parenthood and marital status. Journal of Family Issues, 39(1), 3–27. 10.1177/0192513X15581659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, A.‐P. (2000). Helping substance‐abusing mothers in the child‐welfare system: Turning crisis into opportunity. Families in Society, 81(2), 142–151. 10.1606/1044-3894.1008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sword, W. , Jack, S. , Niccols, A. , Milligan, K. , Henderson, J. , & Thabane, L. (2009). Integrated programs for women with substance use issues and their children: A qualitative meta‐synthesis of processes and outcomes. Harm Reduction Journal, 6(1), 32. 10.1186/1477-7517-6-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam, T. (2019). Addressing stigma: Towards a more inclusive health system. Public Health Agency of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac‐aspc/documents/corporate/publications/chief‐public‐health‐officer‐reports‐state‐public‐health‐canada/addressing‐stigma‐what‐we‐heard/stigma‐eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Taplin, S. , & Mattick, R. P. (2015). The nature and extent of child protection involvement among heroin‐using mothers in treatment: High rates of reports, removals at birth and children in care. Drug and Alcohol Review, 34(1), 31–37. 10.1111/dar.12165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A. , & Kroll, B. (2004). Working with parental substance misuse: Dilemmas for practice. British Journal of Social Work, 34(8), 1115–1132. 10.1093/bjsw/bch132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tuten, M. , Jones, H. E. , & Svikis, D. S. (2003). Comparing homeless and domiciled pregnant substance dependent women on psychosocial characteristics and treatment outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 69(1), 95–99. 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00229-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanoski, K. , Joordens, C. , Kolla, G. , & Milligan, K. (2018). Community networks of services for pregnant and parenting women with problematic substance use. PLoS One, 13(11), e0206671. 10.1371/journal.pone.0206671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson, L. , Poole, N. , Morton Ninomiya, M. , Rutman, D. , Letendre, S. , Winterhoff, T. , Finney, C. , Carlson, E. , Prouty, M. , McFarlane, A. , Ruttan, L. , Murphy, L. , Stewart, C. , Lawley, L. , & Rowan, T. (2019). Collaborative action on fetal alcohol spectrum disorder prevention: principles for enacting the truth and reconciliation commission call to action #33. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(9). 10.3390/ijerph16091589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable – no new data generated.