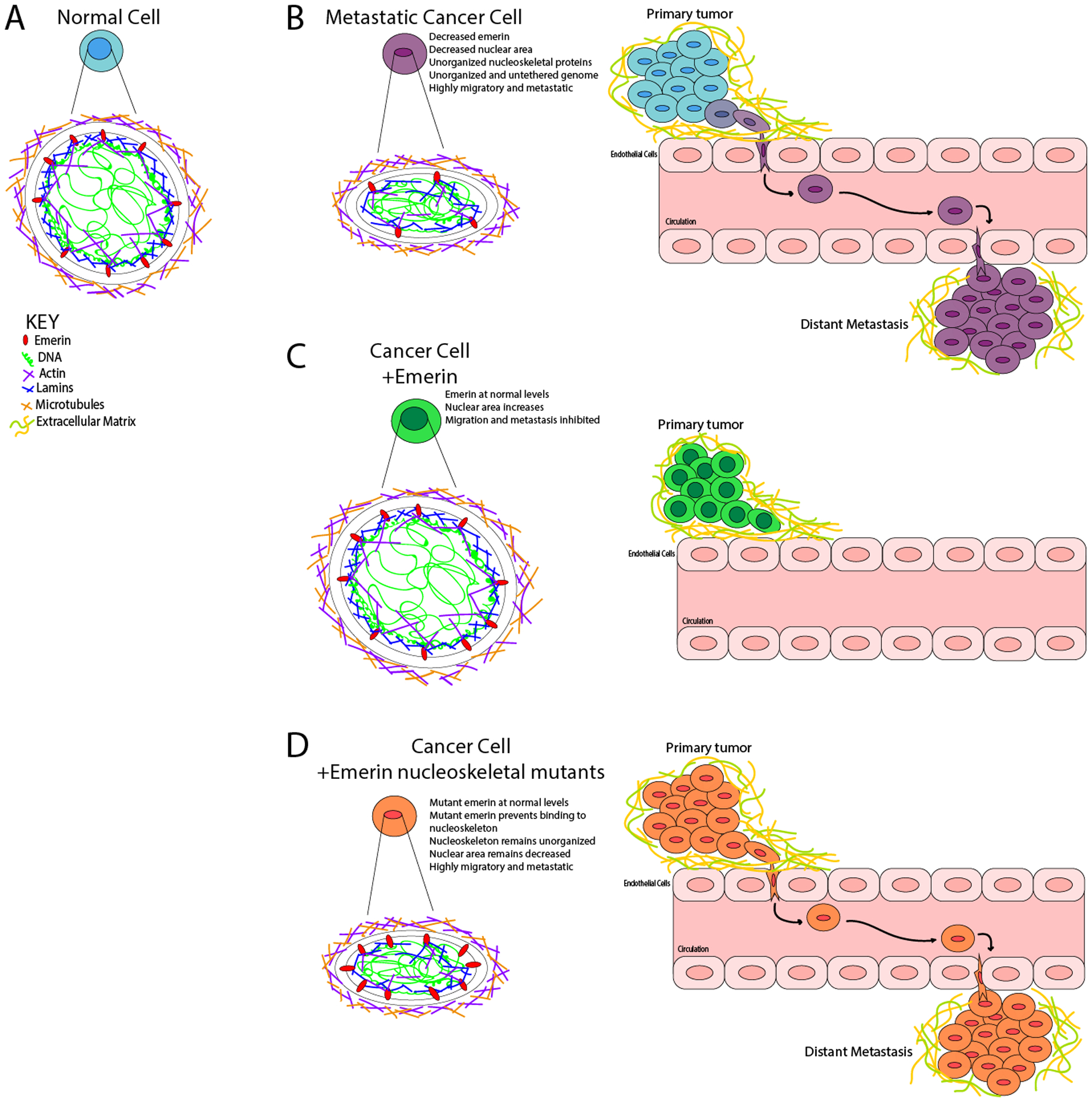

Figure 7: Model for emerin regulation of breast cancer metastasis.

(A) Normal, non-cancerous nuclei are uniformly shaped with an organized nuclear lamina. The forces exerted on the nucleus from the cytoskeleton is countered by the forces within the nucleus, resulting in no deformations. The chromatin is compacted properly with heterochromatin tethered to the periphery and euchromatin centrally localized. (B) In a metastatic cancer cell, there is disruption of nuclear lamina proteins and significantly less emerin. This results in a disorganized nuclear lamina structure. The forces exerted on the nucleus from the cytoskeleton cannot be countered by the nucleoskeleton, resulting in a smaller, deformed nucleus that can easily migrate and metastasize. (C) When emerin is added to an invasive breast cancer cell, the nucleus can now properly organize the nucleoskeleton, which causes the nucleus to increase in size and shape. These changes block intravasation from occurring. (D) When emerin mutants that fail to bind the nucleoskeleton are added to invasive breast cancer cells, the nuclei are unable to reorganize the nuclear lamina properly. This fails to alter the nuclear morphology or size, and thus these cells can still intravasate and metastasize.