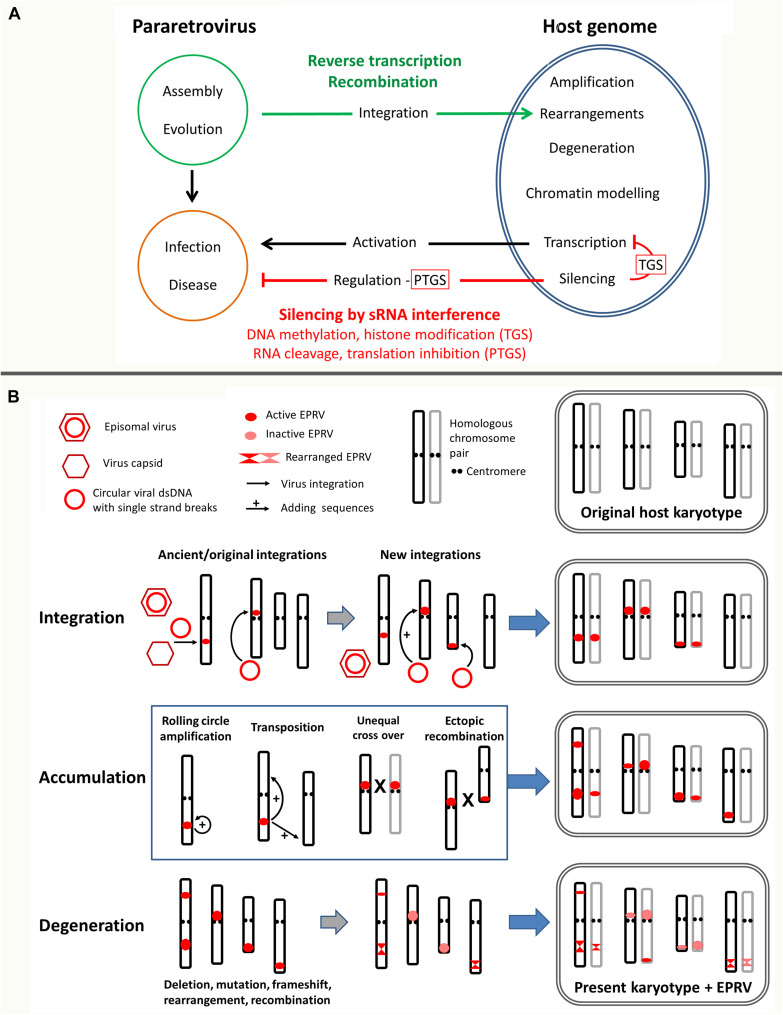

FIGURE 1.

Multiple layers of endogenous pararetrovirus (EPRV) host genome interaction. (A) Overview of involved pathways leading to EPRV invasion of and prevalence in genomes. The ancestral pararetrovirus (PRV) most likely assembled when transcripts of a LTR retrotransposon and an infecting RNA virus recombined allowing systemic plant infection and horizontal transmission. PRVs can become residents of the host genome using illegitimate recombination or reverse transcriptase and accumulate in clusters in certain genomic regions depending on the genomic context and chromatin environment of the host. Endogenous PRVs (EPRVs) usually stay silenced and/or degenerate by mutation, rearrangement or fragmentation (see under b), but sometimes activate. When still active and complete, EPRVs can escape the cellular surveillance system by producing transcripts with terminal repeats. Those serve as template for synthesis of full length PRV episomes that can trigger a viral infection and disease, the same as original episomal PRVs. Furthermore, pararetroviral encoded suppressor of gene silencing counteract the plant defense. EPRV silencing is regulated by RNA interference comprising transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene silencing (TGS and PTGS) as well as DNA methylation and histone modifications (see Figure 2). (B) Detailed view of EPRV interactions with chromosomes. Prevalence of EPRVs are influenced by three steps: integration, accumulation and degeneration. Four chromosomes and their homologs in lighter shade are shown. Size of the red circle/ellipsoid indicates the number of integrations. Steps of integration, accumulation and degeneration, here depicted separately, can happen simultaneously and over a long time period. The present karyotype shows significant changes in EPRV sequences from the ancient integrations; karyotype rearrangements also occur but are not shown. Integration: Tandem arrays and clusters are generated by simultaneous or subsequent integration and over time through backcrosses and selfing the two homologous chromosomes homogenize. Accumulation: Tandemly integrated EPRVs can amplify by several mechanisms shown in the middle box: rolling cycle amplification, transposition of newly synthesized copies using reverse transcription to sites on the same or different chromosome. Unequal recombination (cross overs) between sites on homologous chromosomes or ectopic recombination between heterologous chromosomes (shown as X) will both amplify and reduce the number of copies at given site. Degeneration: As soon as EPRV copies are integrated, the host genome acts by inactivation through epigenetic silencing mechanisms (see Figure 2), but also through sequence degeneration by mutation and deletions that cause frameshifts, fragmentations, rearrangements and recombination.