PURPOSE:

Communication breakdowns in pediatric oncology can have negative consequences for patients and families. A detailed analysis of these negative encounters will support clinicians in anticipating and responding to communication breakdowns.

METHODS:

Semistructured interviews with 80 parents of children with cancer across three academic medical centers during treatment, survivorship, or bereavement. We analyzed transcripts using semantic content analysis.

RESULTS:

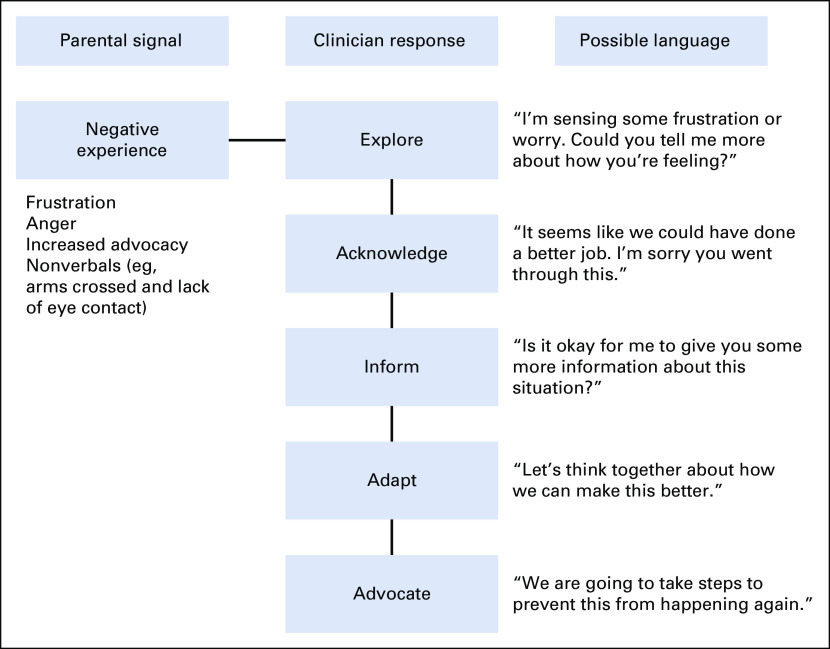

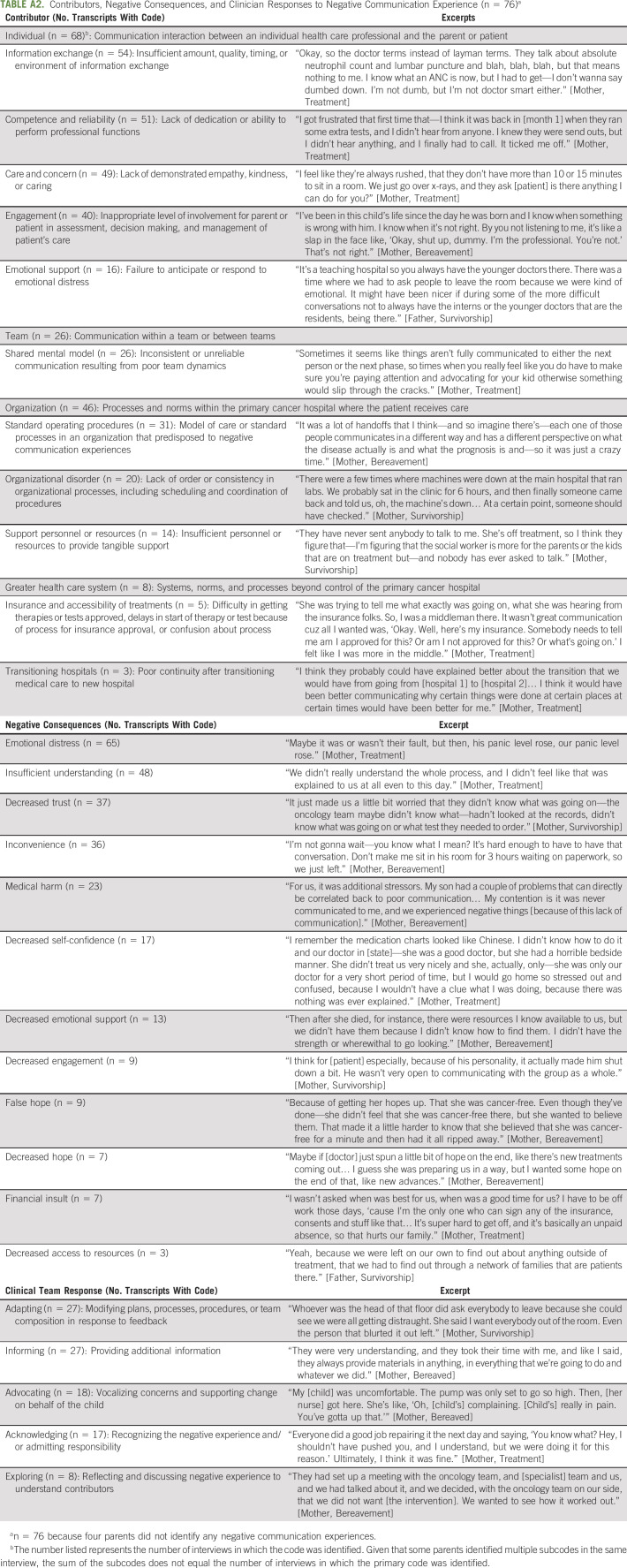

Nearly all parents identified negative communication experiences (n = 76). We identified four categories of contributors to negative experiences: individual (n = 68), team (n = 26), organization (n = 46), and greater health care system (n = 8). These experiences involved a variety of health care professionals across multiple specialties. Parents reported 12 personal consequences of communication breakdowns: emotional distress (n = 65), insufficient understanding (n = 48), decreased trust or confidence (n = 37), inconvenience (n = 36), medical harm (n = 23), decreased self-confidence (n = 17), decreased emotional support (n = 13), decreased engagement (n = 9), false hope (n = 9), decreased hope (n = 7), financial insult (n = 7), and decreased access to resources (n = 3). We identified five categories of supportive responses from clinicians: exploring (n = 8), acknowledging (n = 17), informing (n = 27), adapting (n = 27), and advocating (n = 18). Parents often increased their own advocacy on behalf of their child (n = 47). Parents also identified the need for parental engagement in finding solutions (n = 12). Finally, one parent suggested that clinicians should assume that communication will fail and develop contingency plans in advance.

CONCLUSION:

Communication breakdowns in pediatric oncology negatively affect parents and children. Clinicians should plan for communication breakdowns and respond by exploring, acknowledging, informing, adapting, advocating, and engaging parents in finding solutions.

INTRODUCTION

Communication serves many functions for caregivers of children with cancer, ranging from information exchange and decision making to emotional support and providing validation.1 However, communication efforts can fail, leading to unmet information needs,2–6 inaccurate prognostic understanding,7–9 decisional regret,10 and distrust of clinicians.11 In one study, bereaved parents reported how a single insensitive encounter haunted them and complicated their grief even years later.12

These negative experiences provide an important lens into communication breakdowns. By understanding how communication can fail, clinicians might be able to mitigate harms to families. Yet, the literature exploring negative communication experiences is sparse. One study found that 41% of complaints at a cancer center related to communication breakdowns and lack of respect.13 Another analysis of difficult clinical relationships identified underlying problems of connection and understanding, confrontational parental advocacy, mental health issues, and structural challenges.14 Other studies have identified barriers to specific aspects of communication (eg, shared decision making).15,16

Previous work has not characterized the contributing factors, negative consequences, and recovery attempts related to communication breakdowns in pediatric oncology. A detailed analysis of these experiences will support clinicians in understanding how communication fails, key contributors to breakdowns, and how to mitigate harms. In this study, we characterize contributors, negative consequences, and responses to negative communication experiences in pediatric oncology from the parents' perspective.

METHODS

We report this study following Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research.17

Participants and Recruitment

We interviewed parents of children with cancer from Washington University School of Medicine (St Louis, MO), Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, MA), and St Jude Children's Research Hospital (Memphis, TN) between October 2018 and March 2020. We used stratified sampling, aiming for 12-15 parents per stratum18: time point (treatment ≥ 1 month, survivorship ≥ 6 months, or bereavement ≥ 6 months), child's age at diagnosis (≤ 12 years or ≥ 13 years), and study site. Parents were eligible if they (1) were the parent most involved in communication with clinicians, (2) had a child with cancer ≤ 18 years at time of enrollment or death, and (3) spoke English. We excluded participants who had clinical relationships with authors. We identified participants from review of patient lists, inpatient census, and outpatient schedules and recruited via telephone, mail, and in person. Institutional review boards at all sites approved this study. We did not track the proportion of approached parents who agreed to participate.

Data Collection

We conducted semistructured telephone interviews using an interview guide informed by previous work19–21 and two pilot interviews (Appendix Table A1, online only). Fellows with qualitative research training (B.A.S. and L.J.B.) conducted interviews. We audio-recorded and professionally transcribed interviews. We asked parents to describe bad communication and specific negative communication experiences. We asked, “What made this experience particularly bad” and “What could have made this better?”

Data Analysis

We employed content analysis22,23 by reading transcripts to form ideas, developing initial codes, and refining codes around semantic content. In consultation with all authors, two authors (B.A.S. and J.A.Z.) developed the codebook through iterative consensus coding of 27 transcripts. We defined negative communication experiences as communication encounters that parents described as creating difficulties or undesirable outcomes. We reached thematic saturation for contributors, consequences, and responses to negative experiences. Given the complexity of the codebook, these authors consensus coded all transcripts using Dedoose qualitative software.

RESULTS

Parent Characteristics

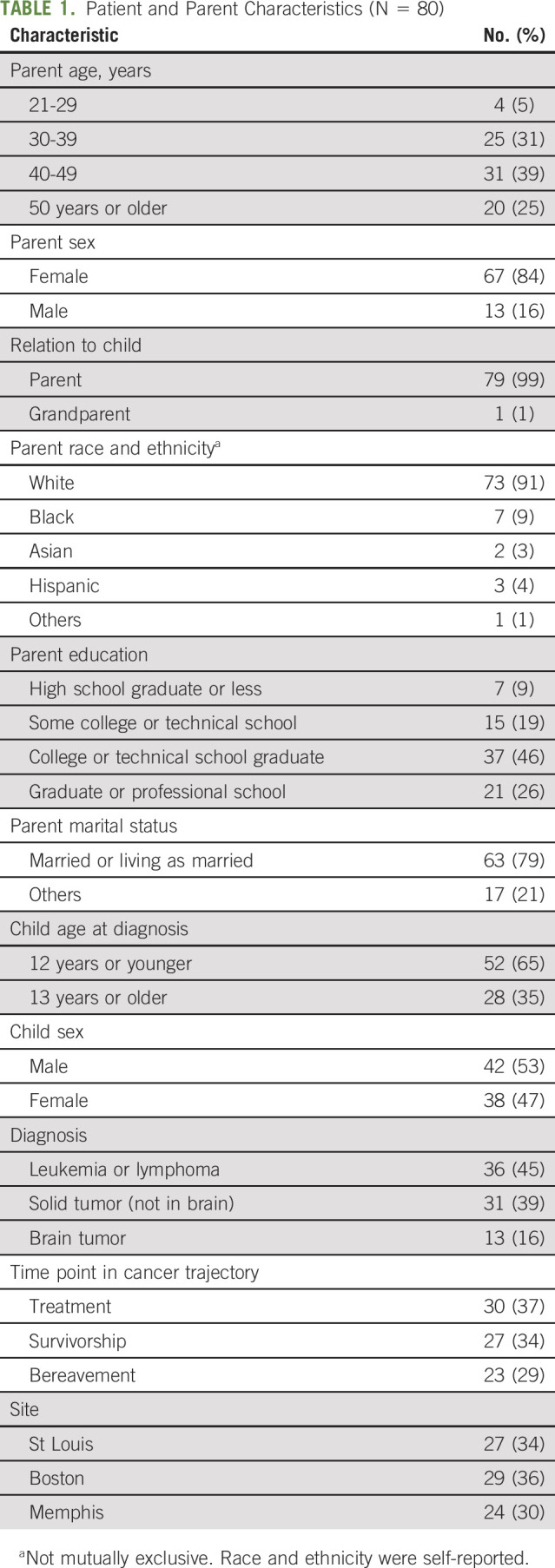

Eighty interviews ranged from 24 to 108 minutes. Parents were predominantly White (91%) and female (84%). Diagnoses included leukemia or lymphoma (45%), solid tumors (39%), and brain tumors (16%) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient and Parent Characteristics (N = 80)

Contributors to Negative Communication Experiences

Parents described negative communication experiences in 76 of 80 (95%) interviews (Appendix Table A2, online only). We categorized the sources of negative experiences as individual, team, organization, or greater health care system. Descriptively, one site appeared to have more negative experiences arising from team issues; otherwise, we did not identify differences based on site or time point.

Individual.

Parents described negative interactions (n = 68) with health care professionals across several specialties: oncology, intensive care, emergency, radiology, surgery, anesthesiology, and supportive care teams.

Parents noted deficiencies in information exchange, related to amount, quality, timing, or environment of communication: “The doctor on call wasn't really telling us what was happening. He would just say, ‘Okay, well, we're gonna take care of this,’ but not really give me definite answer.” [Mother, Survivorship] Parents also described concerns about clinicians' competence or reliability, related to honesty, knowledge, technical skills, or failing to fulfill obligations or promises: “If you say that you're going to do something, if you're gonna visit someone, then you have to make the effort.” Otherwise, it is like “your child's not as important to them.” [Mother, Treatment]

Insufficient care and concern also contributed to negative experiences. Some clinicians used harsh language, failed to show warmth, rushed through visits, or failed to adapt to families' needs: “Comes across in that personality like she was trying to be intimidating, and just really short with any explanations, almost like she was bothered to have to spend any considerable time explaining things.” [Mother, Treatment]

Sometimes, clinicians failed to engage parents or their children in medical care or did not appreciate parental concerns: “I would go to this other medical team and tell [my concerns]… They would just brush it off.” [Mother, Bereavement] Other parents described having too much or too little involvement in care and decision making. “When he was in the pediatric intensive care unit at [hospital], they made me do a lot of the work. I was like, I'm completely uncomfortable with this.” [Mother, Bereavement]

Finally, parents described insufficient emotional support when clinicians failed to anticipate or respond to emotional distress: “They hit you with a lot of info, send you home, and you're lost until you come back and start treatment… We just got punched and then dropped out the door.” [Mother, Bereavement]

Team.

Parents described inconsistent communication resulting from poor team dynamics (n = 26). Some experiences resulted from poor communication between the primary team and specialist teams: “In our experience, I found that often, the parent is expected to remember specific information and update the non-primary team. And I find that, to me, shows a lack of communication. I think that it's important that a parent… isn't expected to be a messenger between two groups.” [Mother, Treatment] Others resulted from poor communication within the oncology team: “Bad or poor communication would be easily summed up in when one set or member of the team is telling you one thing, and the next visit, the next time, or the next set of people that you talk to tells you something that contradicts.” [Mother, Treatment] Parents also described challenges with frequent changes in hospital personnel leading to lack of continuity.

Organization.

Many parents identified hospital processes and norms that contributed to negative experiences (n = 46). Interacting with multiple trainees was frustrating: “They like to bring a bunch of people in when they tell you awful things. I don't know why… So other people can practice telling people awful things?” [Mother, Bereavement] Parents also described frequent changes in team members during inpatient stays, which decreased familiarity. Furthermore, parents noted difficulties with transitions, especially during survivorship: “All of a sudden, you get to five years cancer free, and you go in the survivorship clinics. It's very different. I feel like they should… soothe you into it a little.” [Mother, Survivorship]

Organizations occasionally demonstrated disorder or inconsistency in processes. This disorder manifested in poorly coordinated imaging or laboratory tests and unreliable scheduling practices: “She said, ‘Oh, you need to come in at this time,’ and we'd come in at that time, and it was the wrong day.” [Mother, Bereavement] Some bereaved parents noted the emotional trauma of receiving automated reminders about appointments after their child had died. Other parents described how automated appointment notifications indicated that their child had relapsed or needed additional treatments before the clinical team had discussed with them.

Finally, parents described insufficient personnel or resources to provide support, especially social workers and psychologists: “Right now, in the stage that we're in, I feel like parents need more support. Psychological support… There are things that I need to say to a grown-up who understands what I’m saying, without [patient] there.” [Mother, Survivorship]

Greater health care system.

Parents also described negative communication experiences caused by systems, norms, and processes outside their primary hospitals (n = 8). Parents described communication challenges emanating from insurance companies: “Really, there's no real simple communication when it comes to insurance. I kept getting calls… and they were saying that they were talking to the hospital, but we couldn't track down who at the hospital, they were talking with.” [Mother, Treatment] Parents also noted difficulties when transitioning care to different hospitals, describing poor continuity between institutions.

Consequences of Negative Communication Experiences

Parents identified a range of negative consequences that affected them, their child, or their family (Fig 1, Appendix Table A2). Overall, parents most commonly described additional emotional distress, manifesting as anger, frustration, anxiety, or sadness because of the miscommunication (n = 65). Parents also noted insufficient understanding (n = 48), decreased trust or confidence in the clinical team (n = 37), and inconvenience (n = 36). When specifically describing negative effects on their child, parents most often described emotional distress (n = 29), medical harm (n = 23), decreased emotional support (n = 5), and decreased trust or confidence (n = 3). Medical harms included emergent procedures (eg, intubation, surgery, or chest tubes) because parental warnings were ignored, missing key symptoms or side effects, insufficient pain management, and failed attempts to access central lines because clinicians ignored parental advice.

FIG 1.

Consequences of negative communication experiences.

Responses to Negative Communication Experiences

We identified five categories of supportive clinician responses: exploring, acknowledging, informing, adapting, and advocating (Appendix Table A2). Clinicians explored negative experiences (n = 8) by listening to families and exploring the reasons for miscommunications. Some families found group discussions to be helpful: “I finally just got everybody on the same table and like got 'em all in the room at the same time. I said, okay, you're telling me this and you're telling me this, and it's not matching up. Then we got it all figured out.” [Mother, Survivorship]

Clinicians provided acknowledgment (n = 17) by recognizing miscommunications and admitting responsibility. Sometimes, parents referred to this as being “taken seriously” and listened to: “They were on it quickly. I felt like that was a… perfect sign of great communication in that, number one, they listened. They acted on it. They convened. They figured out how to fix or try to fix, and then they communicated back to me.” [Mother, Treatment] Several parents noted the importance of apologies in repairing relationships.

Clinicians informed families (n = 27) by adjusting the pacing of information, directing families toward reliable information sources, clarifying misconceptions, and providing anticipatory guidance or plans: “She just made me feel better because she explained much further.” [Mother, Survivorship]

Clinicians adapted (n = 27) by modifying plans, procedures, or team composition in response to feedback: “I feel like they did the x-ray just to kind of pacify me, and then she started [having] the pain and then they took it seriously.” [Mother, Treatment]

Clinicians advocated (n = 18) by vocalizing concerns and supporting changes on behalf of the family, and taking steps to prevent future miscommunications: “They were really helpful in advocating and spreading the word. No matter what team of physicians was on or other nurses coming on, that our preference was to round outside, and then come in just so we could regroup.” [Mother, Survivorship]

Parental advocacy was another common response to negative experiences (n = 47). Sometimes, parental advocacy triggered responses from clinicians. Other times, parental advocacy went unheeded. Regardless, parents valued their role as advocates: “You kind of really have to advocate for your child and say what's on your mind. At least you feel like, okay, at least I've said it.” [Mother, Treatment]

Parents also described how increased engagement in finding solutions could have improved these situations (n = 12): “If she had maybe asked me, ‘Okay. I can see that this is very difficult, and this isn't really working, so what do you think I could do better? Or what do you need that would help us along in this process?’” [Mother, Treatment]

To prevent communication breakdowns, one parent suggested planning ahead and assuming communication failures will occur: “Whenever we create some system, I'm actually assuming failure. I'm assuming it will break. I'm assuming I'll need to—there will be an emergency, and I'll have to fix it. How could I make that—either reduce the risk of that, or how could I rapidly fix it once it does break?” [Father, Bereavement]

DISCUSSION

We identified negative communication experiences resulting from failure to fulfill several communication functions,1 with contributing factors at individual, team, organizational, and health care system levels. These breakdowns in functions led to negative consequences for parents, such as insufficient understanding (information exchange), emotional distress (responding to emotions), decreased trust (building relationships), decreased self-confidence (enabling self-management), decreased engagement (providing validation), and diminished hope (supporting hope). Addressing this array of negative experiences can be daunting, especially since many contributors are beyond the oncology team's control.24 However, a deep understanding of contributors to behaviors is essential to support individual and organizational change.25,26 By identifying these contributors, clinicians can devise strategies to prevent or mitigate harms.

Some communication breakdowns are related directly to the oncology team. For example, parents noted poor team dynamics leading to inconsistent information and decreased trust. Focusing on team building and ensuring shared team mental models might improve this communication. Shared team mental models are knowledge structures held by members of a team that enable them to form accurate explanations and expectations for the task and in turn, to coordinate their actions and adapt their behaviors to the demands of the task and other team members.27 Building and reinforcing shared mental models requires intentional effort, open communication, and coordination within the oncology team.28 Teams might improve communication with families by employing communication checklists during team meetings to develop shared mental models, support appropriate distribution and redundancy in communication role assignments, and monitor communication milestones.29,30 Furthermore, teams can improve written documentation in the electronic medical record and work closely with primary pediatricians to support families' communication needs.31

Other communication breakdowns were beyond the oncology team's control. For example, oncologists cannot change the insurance company policies or the family's financial circumstances. Similarly, oncologists might struggle to influence interactions between families and specialists. Even when oncologists cannot prevent negative experiences, they can prepare families with anticipatory guidance and contingency planning. For example, an oncologist might predict struggles with insurance approval, describe how long the process usually takes, collaborate with social workers or care coordinators, and develop contingency plans. Clinicians might also explore financial challenges and make referrals to social workers, financial navigators, and philanthropic organizations. Additionally, organizations should address structural and organizational deficits that negatively affect the family's care experience, especially related to electronic medical records and patient portals.

Communication breakdowns led to an array of negative consequences for families, ranging from emotional distress and decreased trust to medical harm and financial insults. Previous work suggests that such negative experiences might have longstanding effects.12 Data-informed communication interventions might prevent some of these harms. Yet, almost no communication interventions exist in pediatric oncology.20 Past interventions in adult oncology have included communication skills training sessions, question prompt lists, needs assessments, patient navigators, and patient-directed coaching.20 Developing similar interventions in collaboration with parental advisory groups should be a high priority in pediatric oncology.

Parents noted that clinicians responded to their distress with one of five types of responses. We propose that clinicians consider employing these responses in a sequential process of first exploring the parental perspective, acknowledging the impact of the negative experience on the family, informing the parent about additional context they are not aware of, adapting care in safe and reasonable ways, and advocating on behalf of the family to address the source of the difficulty (Fig 2). Following this structured approach might validate parental concerns, facilitate resolution of the negative experience, and repair damage to the clinical relationship. However, this approach requires validation in future studies.

FIG 2.

A proposed five-step response to negative parental experiences.

When clinicians failed to respond, parents increased their own advocacy. Advocating and protecting one's child are key components of good parenting beliefs,32–36 and validating parents in this role is a core communication function.1 However, confrontational parental advocacy could signal diminished trust and unacknowledged communication breakdowns. Misguided parental advocacy can also harm the clinical relationship and exacerbate negative experiences for the family and clinicians. If clinicians notice increased parental advocacy, they might suspect parental distress and begin exploring in a nonjudgmental way. If parents demonstrate significant anger, clinicians should employ mediation techniques while exploring the parent's concerns.37

Communication breakdowns will happen, no matter how caring or diligent the clinical team. This is especially true as clinicians are asked to fulfill more roles (eg, documentation, increased patient loads, and facilitating care coordination) for increasingly complex patients without additional time or support. Clinicians might follow the advice of one parent by assuming it will break and making plans to prevent or mitigate negative consequences. Preventive efforts are important, but clinical teams should also make plans to address probable communication failures, whether they are in the control of the clinical team or not. Effective responses likely depend on maintaining strong relationships with families, remaining attuned to the family's distress, acknowledging and apologizing, and developing plans to address underlying concerns.38

This study should be interpreted in light of limitations. Parents were English-speaking and predominantly White, well-educated mothers. Parents of children with brain tumors and older children were under-represented. Non–English-speaking parents were excluded. Future studies should engage with larger samples of under-represented communities to ensure that all voices are included. Parents might have also been affected by recall bias or conformity bias, especially when discussing negative experiences. All participants received care from large academic medical centers; it is unclear to what extent these findings can generalize to other settings. Finally, we did not address patients' perspectives in this study.

Communication in pediatric oncology is complex, and communication breakdowns will occur. These breakdowns can lead to negative consequences for families. Clinicians should assume that communication will occasionally fail and consider responding by exploring, acknowledging, informing, adapting, advocating, and engaging the family in finding solutions.

Appendix

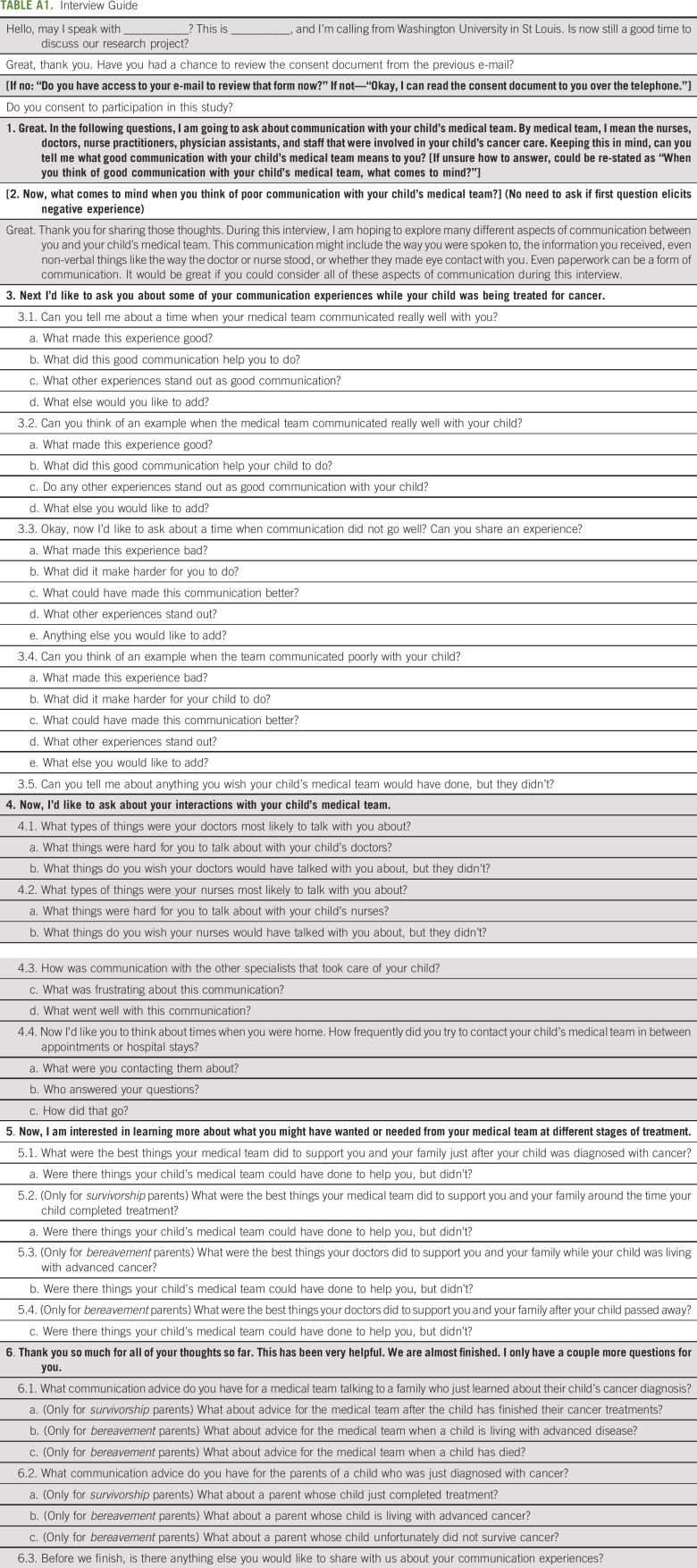

TABLE A1.

Interview Guide

TABLE A2.

Contributors, Negative Consequences, and Clinician Responses to Negative Communication Experience (n = 76)a

James M. DuBois

Consulting or Advisory Role: Centene Corp

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR002345) and the Conquer Cancer Foundation Young Investigator's Award.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Bryan A. Sisk, Jennifer W. Mack, James M. DuBois

Financial support: Bryan A. Sisk, Justin N. Baker

Administrative support: Justin N. Baker, Jennifer W. Mack

Provision of study materials or patients: Byan A. Sisk, Justin N. Baker

Collection and assembly of data: Bryan A. Sisk, Lindsay J. Blazin, Justin N. Baker

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Assume It Will Break: Parental Perspectives on Negative Communication Experiences in Pediatric Oncology

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

James M. DuBois

Consulting or Advisory Role: Centene Corp

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sisk BA, Friedrich A, Blazin LJ, et al. : Communication in pediatric oncology: A qualitative study. Pediatrics 146:e20201193, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenzang KA, Fasciano KM, Block SD, et al. : Early information needs of adolescents and young adults about late effects of cancer treatment. Cancer 126:3281-3288, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sisk BA, Greenzang KA, Kang TI, et al. : Longitudinal parental preferences for late effects communication during cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65:e26760, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenzang KA, Cronin AM, Kang T, et al. : Parent understanding of the risk of future limitations secondary to pediatric cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65:e27020, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sisk BA, Fasciano K, Block SD, et al. : Longitudinal prognostic communication needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer 126:400-407, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sisk BA, Kang TI, Mack JW: Prognostic disclosures over time: Parental preferences and physician practices. Cancer 123:4031-4038, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mack JW, Cronin AM, Uno H, et al. : Unrealistic parental expectations for cure in poor-prognosis childhood cancer. Cancer 126:416-424, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenberg AR, Orellana L, Kang TI, et al. : Differences in parent-provider concordance regarding prognosis and goals of care among children with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:3005-3011, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Figueroa Gray M, Ludman EJ, Beatty T, et al. : Balancing hope and risk among adolescent and young adult cancer patients with late-stage cancer: A qualitative interview study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 7:673-680, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sisk BA, Kang TI, Mack JW: The evolution of regret: Decision-making for parents of children with cancer. Support Care Cancer 28:1215-1222, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mack JW, Kang TI: Care experiences that foster trust between parents and physicians of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 67:e28399, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, et al. : Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 156:14-19, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mack JW, Jacobson J, Frank D, et al. : Evaluation of patient and family outpatient complaints as a strategy to prioritize efforts to improve cancer care delivery. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 43:498-507, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mack JW, Ilowite M, Taddei S: Difficult relationships between parents and physicians of children with cancer: A qualitative study of parent and physician perspectives. Cancer 123:675-681, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Udo C, Kreicbergs U, Axelsson B, et al. : Physicians working in oncology identified challenges and factors that facilitated communication with families when children could not be cured. Acta Paediatr 108:2285-2291, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boland L, Graham ID, Légaré F, et al. : Barriers and facilitators of pediatric shared decision-making: A systematic review. Implement Sci 14:7, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J: Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19:349-357, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L: How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18:59-82, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sisk BA, Friedrich AB, Mozersky J, et al. : Core functions of communication in pediatric medicine: An exploratory analysis of parent and patient narratives. J Cancer Educ 35:256-263, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sisk BA, Schulz GL, Mack JW, et al. : Communication interventions in adult and pediatric oncology: A scoping review and analysis of behavioral targets. PLoS One 14:e0221536, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sisk BA, Mack JW, Ashworth R, et al. : Communication in pediatric oncology: State of the field and research agenda. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65:10.1002/pbc.26727, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE: Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15:1277-1288, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T: Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 15:398-405, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sisk BA, Friedrich A, Kaye E, et al. : Multilevel barriers to communication in pediatric oncology: Clinicians' perspectives. Cancer 127:2130-2138, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. : Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 4:1-15, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pugh DS: Organizational behaviour: An approach from psychology. Hum Relat 22:345-354, 1969 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cannon-Bowers J, Salas E, Converse S: Shared mental models in expert team decision-making, in Castellan NJ., Jr (ed): Individual and Group Decision Making: Current Issues. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 2001, pp 221-246 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kosty MP, Hanley A, Chollette V, et al. : National Cancer Institute-American Society of Clinical Oncology teams in cancer care project. J Oncol Pract 12:955-958, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sisk BA, Dobrozsi S, Mack JW: Teamwork in prognostic communication: Addressing bottlenecks and barriers. Pediatr Blood Cancer 67:e28192, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dobrozsi S, Tomlinson K, Chan S, et al. : Education milestones for newly diagnosed pediatric, adolescent, and young adult cancer patients: A quality improvement initiative. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 36:103-118, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SJ, Clark MA, Cox JV, et al. : Achieving coordinated care for patients with complex cases of cancer: A multiteam system approach. J Oncol Pract 12:1029-1038, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feudtner C, Walter JK, Faerber JA, et al. : Good-parent beliefs of parents of seriously ill children. JAMA Pediatr 169:39-47, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hill DL, Faerber JA, Li Y, et al. : Changes over time in good-parent beliefs among parents of children with serious illness: A two-year cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage 58:190-197, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.October TW, Fisher KR, Feudtner C, et al. : The parent perspective: “Being a good parent” when making critical decisions in the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med 15:291-298, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weaver MS, October T, Feudtner C, et al. : “Good-Parent beliefs”: Research, concept, and clinical practice. Pediatrics 145:e20194018, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, et al. : “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol 27:5979-5985, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fiester A: Contentious conversations: Using mediation techniques in difficult clinical ethics consultations. J Clin Ethics 26:324-330, 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sisk B, Baker JN: A model of interpersonal trust, credibility, and relationship maintenance. Pediatrics 144:e20191319, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]