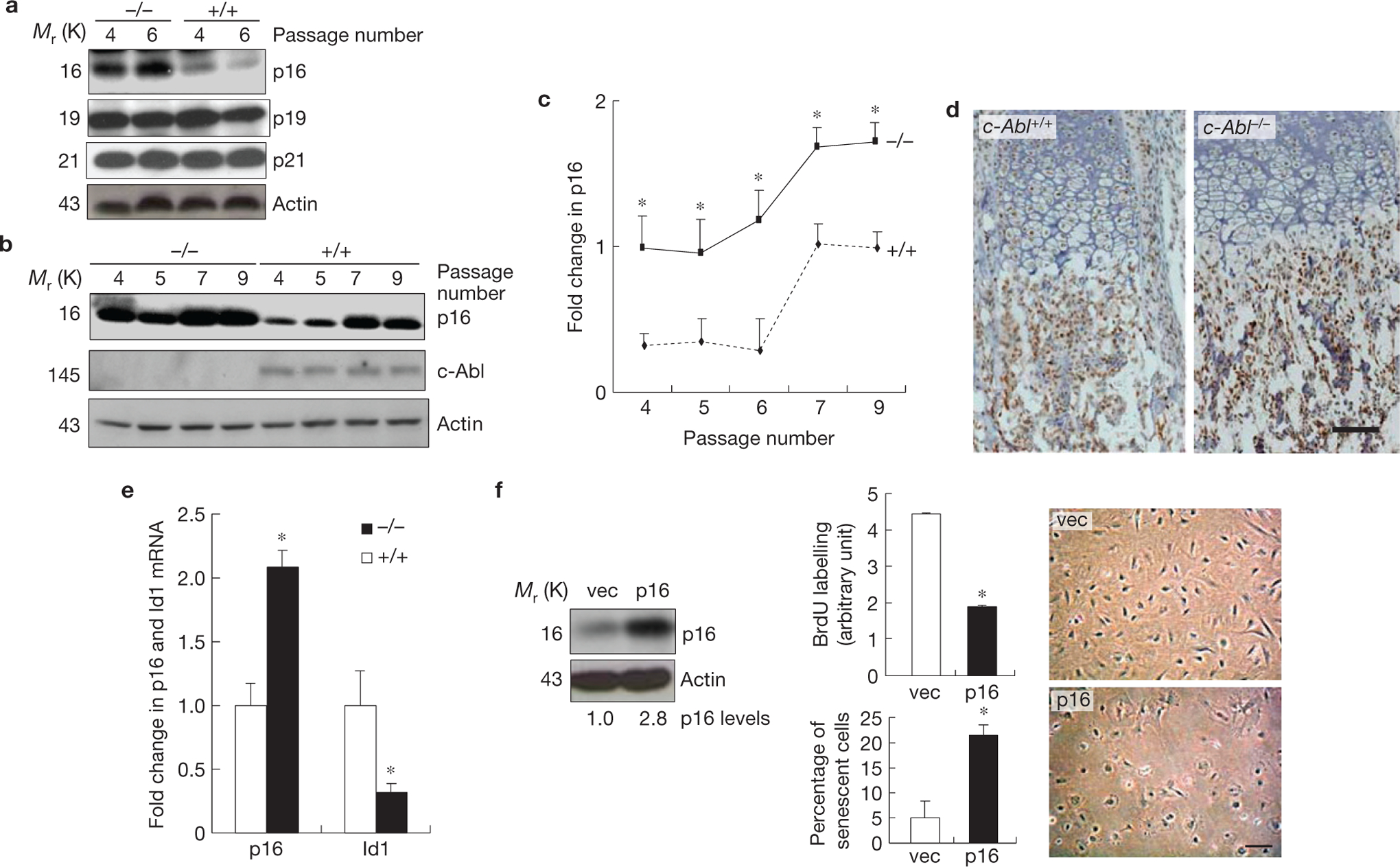

Figure 2.

c-Abl−/− osteoblasts showed p16INK4a upregulation, which is responsible for premature senescence. (a) c-Abl−/− osteoblasts expressed increased levels of p16INK4a, but not p19 or p21, during replicative senescence. Mutant and WT osteoblasts were cultured as in Fig. 1c. At day three of the passages indicated, cells were collected and the same amounts of total protein were analysed by western blot. (b) Expression of p16INK4a in c-Abl−/− and control osteoblasts during the passaging of the cells. (c) Quantification results of a and b combined. (d) Immunohistological staining of p16INK4a on bone sections of newborn pups. Note that the difference mainly exists in the area occupied by osteoblasts, but not areas occupied by chondrocytes. For c-Abl expression, see Supplementary Fig. S2b. (e) Real-time PCR results show that c-Abl−/− femurs exhibited an increase in the mRNA levels of p16INK4a and a decrease in Id1. Total RNA was isolated from femurs of three c-Abl−/− and WT mice. The smaller increase in p16INK4a than cell cultures might be caused by inclusion of non-osteoblast cells, which may not behave like osteoblasts in Id1 and p16INK4a expression. (f) Ectopic expression of p16INK4a led to senescence-like phenotypes. WT osteoblasts were infected with empty retroviruses or viruses expressing p16INK4a, selected against puromycin, and cultured. Left panel: western blot showing the levels of p16INK4a; middle panels: BrdU incorporation (upper) and percentages of SA-β-Gal-positive cells (bottom); right panel: cell morphology change in p16INK4a-expressing cells. Scale bars, 50μm. Data are means ± s.e.m. (n = 3). *P < 0.05 when compared to WT counterparts. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S8.