Abstract

Background:

News media create a sense-making narrative, shaping, reflecting and enforcing cultural ideas and experiences. Reportage of COVID-related death and bereavement illuminates public perceptions of, and responses to, the COVID-19 pandemic.

Aim:

We aimed to explore British newspaper representations of ‘saying goodbye’ before and after a COVID-related death and consider clinical implications.

Design:

Document analysis of UK online newspaper articles published during 2 week-long periods in March–April 2020.

Data sources:

The seven most-read online newspapers were searched: The Guardian, The Daily Mail, The Telegraph, The Mirror, The Sun, The Times and The Metro. Fifty-five articles discussed bereavement after a human death from COVID-19, published during 18/03–24/03/2020 (the UK’s transition into lockdown) or 08/04–14/04/2020 (the UK peak of the pandemic’s first wave).

Results:

The act of ‘saying goodbye’ (before, during and after death) was central to media representations of COVID bereavement, represented as inherently important and profoundly disrupted. Bedside access was portrayed as restricted, variable and uncertain, with families begging or bargaining for contact. Video-link goodbyes were described with ambivalence. Patients were portrayed as ‘dying alone’ regardless of clinician presence. Funerals were portrayed as travesties and grieving alone as unnatural. Articles focused on what was forbidden and offered little practical guidance.

Conclusion:

Newspapers portrayed COVID-19 as disruptive to rituals of ‘saying goodbye’ before, during and after death. Adaptations were presented as insufficient attempts to ameliorate tragic situations. More nuanced and supportive reporting is recommended. Clinicians and other professionals supporting the bereaved can play an important role in offering alternative narratives.

Keywords: Bereavement, grief, pandemics, end of life, mass media, coronavirus infections, COVID-19

What is already known about the topic?

During COVID-19, infection control measures have prevented many family members from being with seriously ill or dying loved ones, and impacted on after-death mourning practices and bereavement.

Clinicians and funeral officiants have tried to mitigate the impact of infection control measures, for example, using video-technology; however, this has not been done consistently and its acceptability is unknown.

The news media play an important role in creating a sense-making narrative, reflecting and enforcing cultural ideas and shaping experiences of illness and bereavement.

What this paper adds

Online UK newspapers focused on how COVID-19 disrupted ‘saying goodbye’ (prior to death, at the moment of death and after death) and conflicted with cultural understandings of a ‘good death’ and ‘good grief’, despite efforts undertaken to mitigate the effects of restrictions.

Findings demonstrate a prevailing uncertainty, fear and anxiety regarding: changes to practice; control over access to people who have been hospitalised; the possibility of dying alone or having loved ones die alone; and being unable to properly commemorate a death.

Articles focused on what was forbidden rather than permitted and offered little practical guidance for the public.

Implications for practice and policy

Understanding the media representations and cultural narratives around a ‘good death’ and ‘good grief’ that influence patients’ and families’ fears and anxieties can help inform person-centred care and bereavement support.

Clinicians should explore with families ways of finding meaningful connection and of saying goodbye despite restrictions, and, alongside other bereavement support providers and hospital press officers, should offer alternatives to exaggerated or inaccurate media narratives.

More could be done in media reporting to portray diverse experiences and offer practical advice to members of the public dealing with serious illness and bereavement during the pandemic.

Background

COVID-19 is an unparalleled modern pandemic that has to date caused over 2.34 million deaths worldwide, 1 leaving an estimated 21 million bereaved. 2 The pandemic has transformed lives and health systems, and become the primary global media focus. In the UK, online newspaper readership increased by 6.6 million in the first quarter of 2020 as a result of the pandemic. 3

COVID-19 death and bereavement present unique challenges for clinicians, patients and families.4,5 Deaths are often sudden and unexpected. Infection control restrictions can isolate people from their loved ones during illness, death and grief. Inability to say goodbye in person, social isolation and a lack of social support are known risk factors for poor bereavement outcomes.6–9 Funerals provide support and help mourners process grief, 10 but restrictions on the numbers of mourners, the need to self-isolate and travel restrictions have prevented many bereaved people from having the service they would have wanted. Clinicians and funeral professionals mitigated these restrictions by enabling adapted access (e.g. via videolinks 11 ), but there is a lack of evidence to inform these innovations and their acceptability to mourners is as yet unknown.

Accounts of restrictions and adaptations, and their consequences for bereaved people, have featured extensively in UK news media. Previous research has examined media representations of ‘good’ deaths 12 and grief, 13 demonstrating the media’s central role in creating sense-making narratives, reflecting and enforcing cultural ideas about death and bereavement. 14 Analysis of the reportage surrounding COVID-related death and bereavement illuminates public perceptions of the pandemic and the role of professionals providing end-of-life care. We aimed to explore newspaper representations of leave-taking, or ‘saying goodbye’, before and after death during the first wave of COVID-19 in the UK.

Methods

We conducted a document analysis of online newspaper articles exploring how the UK media represented people’s experiences of the end of life and bereavement when someone they knew had died from COVID-19. Our approach was informed by critical discourse analysis of documents, 15 aiming to understand how newspaper discourse implicitly and explicitly described experiences of people bereaved by COVID-19, and the implications of such bereavement. Critical discourse analysis is concerned with identifying and examining the ideologies embedded in discourse (e.g. in this article, what ‘saying goodbye’ should look like) and their social and material consequences. 16 Consequently, our premise was that newspaper discourses are not neutral; they have power to impact how bereavement is experienced, influence societal discussions about what is considered ‘normal’ for bereavement, and can impact professional practices and policies. This approach acknowledges that what is considered ‘normal’ or ‘expected’ in relation to death, bereavement and grief can be understood as social constructs, informed by and replicated in societal discourses, and that these can vary cross-culturally.17–19 Our multistage analytical process involved reading, coding and interpreting each of the texts to identify recurring narrative patterns and themes within and across documents and to consider these in relation to existing social theories about death, grief and bereavement as well as media reporting on death. We further discuss our methods and the general narratives we identified in a separate publication 20 ; here we focus on discourses related to ‘saying goodbye’ and consider implications for end-of-life care and bereavement support. By focusing on the different ways in which the media articles discussed ‘saying goodbye’, we were able to identify several distinct narratives around this process which we have organised into themes to illustrate both the narratives and the normative social constructs that were present within them. The research team comprised a social scientist (LS), medical anthropologist (EB) and healthcare researcher and speech and language therapist (RS).

Data collection

Publication selection

The seven most-read online UK newspapers and their Sunday counterparts were included: The Guardian, The Daily Mail, The Telegraph, The Mirror, The Sun, The Times and The Metro. 21 These publications cross readership demographics and the political spectrum. 22 They represent a range of newspaper types: former broadsheets, a middle market tabloid and tabloids.

Search strategy

We searched each newspaper’s search engine using the following key words as Boolean searches: grief or bereavement, and COVID-19 (and variants Covid 19 and sars-cov-2), coronavirus or pandemic. Searches were completed for a 4-week time period (18/03–14/04/2020), a timespan covering the transition into lockdown and the extension of the lockdown period.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included articles from specified news sources describing grief and bereavement after a human death from COVID-19.

We excluded articles written for a non-UK audience (e.g. the ‘Australia’ section of The Daily Mail); articles including a key word but not specifically related to human death; obituaries; articles discussing bereavement unrelated to COVID-19; and articles discussing non-bereavement related grief.

The search yielded high numbers of relevant articles (Table 1). Two week-long search periods were selected for analysis to encompass possible changes in reporting of the COVID-19 pandemic. The first week (week A: 18/03–24/03/2020) covered the UK’s transition into lockdown; the fourth week (week B: 08/04–14/04/2020) occurred at the first peak of the pandemic. Supplementary File 1 shows the number of included articles by date, alongside total deaths to date and key events.

Table 1.

Search results by publication and date range.

| The Guardian (G.) |

The Daily Mail (DMa.) | The Telegraph (Te.) | The Mirror (TMi.) | The Sun (S.) | The Times (Ti.) | The Metro (Me.) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18/03/2020–24/03/2020 (week A) | 3 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 19* |

| 25/03/2020–31/03/2020 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 20 |

| 01/04/2020–07/04/2020 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 36 |

| 08/04/2020–14/04/2020 (week B) | 1 | 20 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 36* |

| Total by publication title | 11 | 40 | 9 | 15 | 18 | 8 | 10 | 111 |

Included in the analysis.

Data analysis

Document analysis of the articles’ text was conducted, examining how behaviour and events were placed in context and identifying themes, ‘frames’ and discourse. 23 Our analysis conceptualised ‘saying goodbye’ as a social construct and dying as a social process, 24 and was inductive, aiming to identify and understand the narratives within the data. The co-authors independently extrapolated themes from three articles. These were discussed as a group and organised into a hierarchical coding frame of defined themes and sub-themes (LS). Coding focused on manifest themes (types/aims of articles, framing of the subject), latent themes (implicit content, use of metaphors/symbols, contradictions) and trends/differences across time and publications. Such an approach is consistent with critical discourse analysis 25 and helps identify and report upon meaningful categories, in this case how ‘saying goodbye’ was described within the discourse during the early stages of the pandemic and the consequences of this.

Once finalised, RS applied the coding frame to the data, meeting with co-authors regularly to discuss the analysis, with a particular focus on how the data related to existing theoretical and empirical critical understandings of media representations of death and bereavement and the normative narratives within the data. Additional emergent themes were added as needed and applied consistently across the dataset. NVivo 12 was used for data management.

Data extracts are tagged with a unique ID number, denoting publication name (Table 1), week and article number (e.g. Ti.A.15 = Times article, Week A, 15th article in the dataset). Quotation marks in data extracts indicate quotes used within articles.

Results

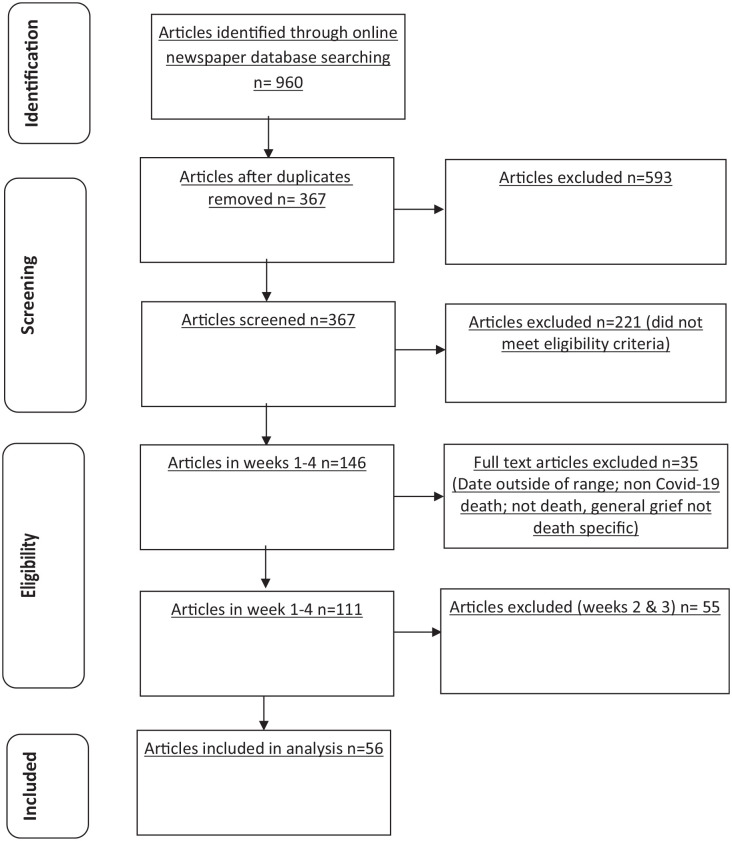

Fifty-five articles were analysed (19 Week A; 36 Week B) (Figure 1, Table 1). The Daily Mail carried the most articles across both weeks (Week A = 8; Week B = 20).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

Media representations of COVID-related bereavement focused on profound disruption to the act of ‘saying goodbye’ before and after death; acts portrayed as important closure rituals intrinsic to the processes of dying and grieving. Disruptions were reported at three main stages: prior to but close to death (e.g. when a person was being treated in an Intensive Care Unit), at or shortly after the moment of death (e.g. being present at the deathbed) and after the death (e.g. arranging and attending a funeral). Newspapers used the term ‘final goodbye’ to describe closure or comforting contact occurring at any of these stages.

As disruptions to the first and second stages were often discussed together, we present findings in two themes, with sub-themes: Saying goodbye prior to and/or at the moment of death (Control over access; Adapting health and social care services; Effects on relatives and staff; A good death, a bad death); Saying goodbye after death (Adaptations to post-death practices and effects on the bereaved; Role of the funeral; Grieving alone). Themes, sub-themes and exemplifying data extracts are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Themes and sub-themes with example data extracts.

| Major theme (definition) | Sub-theme | Exemplars |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Saying goodbye prior to death and at the moment of death (impact of coronavirus on relatives’ experiences of ‘saying goodbye’ to their seriously ill or dying relatives) | Control over access | T.B.27: ‘They let us have 10 min with him. It was like he was just asleep. He had so many tubes and wires in him’, Mrs Martin told Today on BBC Radio 4. ‘We just told him that we loved him and it was heartbreaking to hear the children tell him they were going to make him proud. We were really glad to have that time with him’. |

| Adapting health and social care services | G.A.10: ‘people are having to use videolinks to say their last goodbyes to dying relatives because hospitals are curtailing visits to curtail the spread of the virus’ | |

| Effects on relatives and staff | DMa.B.29: ‘heartbreaking photographs of a doctor wailing on the doorstep of her New York medical practice after losing her mother to coronavirus emerged on Thursday and lay bare the grief of the pandemic’ | |

| Latent: A good death, a bad death | TMi.A.6: ‘speaking for the first time, her grieving husband. . . said the couple, from near Hertford in Hertfordshire, gazed into each other’s eyes, said “I love you” and exchanged goodbyes “for a few minutes” before she died’ | |

| 2. Saying goodbye after death (impact of coronavirus on relatives’ experiences during bereavement) | Adaptations to post-death practices and effects on the bereaved | Te.A.1: ‘The Church of England insisted that it is looking at ways to use technology, such as Skype, recordings and memorials, so that grievers are able to properly mourn their loved ones once the current restrictions lift’ |

| Role of a funeral | G.B.52: ‘They were amongst increasing numbers of grieving people who are being denied the opportunity to say a final goodbye to their loved ones, leaving celebrants, priests and funeral directors to stand in as “proxy mourners”’. | |

| Grieving alone | Me.A.16: ‘A man is asking members of the public to send his grandma letters to keep her going after her husband died, meaning she now has to isolate completely alone. Isolation is tough on everyone over 70, or in vulnerable groups, but for Zac France’s grandmother Sheila, she is also dealing with grief – and she has to do it without any physical interaction with her loved ones’. |

Week A articles mainly focused on funeral guidance, early deaths in the UK and deaths and funeral practices overseas. Week B articles focused more on UK deaths counts, comparison of the UK situation with that of other countries, and tragic stories.

Saying goodbye prior to and at the moment of death

Media coverage focused on how restrictions introduced to control the spread of COVID-19 disrupted the usual rituals of saying goodbye, including relatives’ access to the bedside, opportunity to see or talk to a dying loved one and ability to touch and comfort them during death.

Control over access

Articles typically portrayed hospitals as controlling bedside access, with families ‘begging’ and bargaining for access (e.g. offering to supply their own personal protective equipment (PPE)).

‘She did not make it to the hospital in time and she was even told that she would not even be allowed to see her husband’s body, but [she] insisted.’ Dma.B.43.

Overall, access was portrayed as variable, uncertain and dependent on the kindness, availability or flexibility of staff. One bereaved wife reported:

‘A nurse said she would stay after her shift had ended so the family could make a final visit’ Ti.B.27.

Some Week A articles described PPE-assisted visits; others described blanket visiting bans. Week B articles included more mentions of physical visits, though often in non-UK contexts. Restrictions were typically reported through human interest stories rather than reporting on policies. Barriers to access were reported passively, with no explicit apportioning of blame. None of the articles provided editorial perspectives on inconsistencies or suggested better practice; however, there was an implicit sense of injustice in the discrepancies, compounded by the sudden nature of the deaths and reports of problems accessing PPE and COVID testing.

Adaptations to health and social care services

Articles described adapted goodbye rituals, which were often time-limited, using videolinks or PPE (with varying permissibility of physical contact with or without PPE). Articles described both two-way conversations at the end of life and goodbyes delivered during sedation. Some bereaved people reported gratitude at such adapted goodbyes; one clinician reported that viewing a death via videolink had benefited family members:

‘she added that the family had found it to be a difficult experience but one that helped them to understand what was happening’ G.A.10.

Others described the experience as distressing; a bereaved son was quoted as saying:

‘praying for your loved one wearing masks and gloves is what nightmares feels like’. Dma.B.22.

Some articles described relatives making in-person visits after clinicians explained the risks, with some having to self-isolate afterwards (often leaving bereaved people grieving alone, unable to attend after-death services). The potential long-term emotional burden of these difficult choices was not discussed.

Effects on relatives and staff

Deaths were typically described as unexpected, and the deceased as ‘victims’. Across both weeks, experiences of these sudden bereavements were reported emotively, using terms such as ‘heartbreak’, ‘devastated’, ‘agony’ and ‘trauma’. Emotive and sensationalist language was particularly common in tabloid papers, while broadsheets tended to limit emotive language unless quoting others. Bereaved people were reported as not knowing how to cope. Stoicism was encouraged: readers were advised by bereaved family members ‘to “be strong” for their families’ (Dmi.A.6).

Clinicians’ prominence in bereavement narratives shifted. In Week A, the effects of deaths on clinicians were rarely discussed. Week B increased focus on clinicians’ emotional state, using language previously associated with personally bereaved people. One article stated ‘NHS staff. . . are frank about the toll it takes, both physical and emotional’ (S.B.26), hinting at the emotional challenges of clinical work, perhaps because clinicians were at this time also experiencing from the death of their colleagues or family members.

A good death, a bad death

This primarily latent theme refers to how media representations of COVID-19 conflict with assumed cultural understandings of a good death. Newspapers focused on what was missing in a COVID-19 death, with these absences framed in terms of tragedy, shock and upset:

‘The agony of saying goodbye to both the men in her life was compounded further by the fact she was unable to be with them during their final moments, unable to comfort either. Unable to say goodbye.’ Dma.B.43.

The perceived trauma and injustice of ‘dying alone’ without a loved one present was presented as a ‘worst case scenario’ in reportage, though it was typically addressed implicitly:

‘That means loved ones are cut off from their families at precisely the time they need them most’ G.A.10.

People were described as ‘dying in quarantine’ (TMi.A.12) due to restricted access and the risk to clinically vulnerable family members, and as ‘dying alone’ even when clinicians were present.

To mitigate a ‘bad’ death (or best approximate a ‘good’ death), clinicians were reported to deem technological adaptations and clinicians’ presence reasonable compromises, saying they would ‘do their utmost to ensure none of [the dying patients] feel frightened or alone’ (G.A.10). However, reporting suggested that being physically absent at a death was always distressing for the bereaved, and therefore that personal communication, presence and touch are irreplaceable cultural features of a ‘good death’.

Saying goodbye after death

This theme encompasses disruption of post-death grieving processes, focusing on bereaved people and funeral practices. Week A articles typically focused on deaths and funerals, using dramatic Italian and American examples (including refrigerated lorries as temporary mortuaries) to suggest possibilities for the UK. Week B articles typically shifted to personal stories of death and funeral planning, increasingly conveying compounded grief and trauma across all stages of saying goodbye.

Role of the funeral

Funerals were positioned as ‘vital’: offering a chance to say a ‘proper’ or ‘final goodbye’ with dignified tributes to loved ones, thereby helping the grief process. Funeral practices were ‘ancient rituals’ (Dma.A.19) under threat from COVID-19:

‘[The pandemic is] reshaping many aspects of death, from the practicalities of handling infected bodies to meeting the spiritual and emotional needs of those left behind’ Dma.A.19.

Despite commonly reporting that COVID-19 affected everyone ‘regardless of culture or religion’ (Dma.1.5), newspapers focused almost exclusively on Christian or secular post-death practices, with disruption to other traditions only mentioned in a global context.

Adaptations to post-death practices and effects on the bereaved

Across publications, articles typically focused on what was forbidden, rather than permitted, under pandemic response guidelines. Some reportage of the impact on after-death practices focused on policy and guidance, interpreting the apparently unclear restrictions and describing adaptations, while other reportage framed restrictions as ‘bans’ on certain practices. Restrictions discussed included the number of mourners at funerals, physical contact (between mourners, and with the deceased), singing, open caskets, pallbearers and choice of burial attire. Several articles acknowledged other disruptive factors including travel restrictions and relatives’ need to self-isolate.

Articles used emotive calls-to-action from interviewees, including the Archbishop of Canterbury requesting authorities ‘not to treat coronavirus victims “like cattle” and to give them a dignified burial’ (DMa.B.49). Funerary professionals pushed for fewer restrictions and equity across practices nationwide, with some reported as calling for an all-or-nothing approach to funerals to address inequity. First-hand accounts from funeral-goers conveyed a discrepancy between expected and adapted funerals. Some funeral officials reportedly provided live-streamed services, sharing prayers and readings by email and offering online books of remembrance. Other articles described the possibility of holding a burial now and a service in the future.

The impact of funeral restrictions was described as unjust: a failure to honour the deceased with something they ‘deserved’ or had ‘earned through life’ and unfair on bereaved people.

‘“It seems so unfair” [she] said. “I can’t even give them a proper burial. I just have to put them in a box and put them into a hole.”’ Dma.B.43.

Longer-term effects were hypothesised, with a celebrant speculating that the impact on bereaved people would be ‘“profound and last a long time”’ (G.B.52).

Families were generally reported as accepting the rationale behind restrictions, but nevertheless described them as devastating ‘travesties’ associated with guilt and shame:

‘“The ceremony was impeccable, except there was no one there who should have been there. I felt my mother was alone. ‘“The ceremony was impeccable, except there was no one there who should have been there. I felt my mother was alone.”’ G.B.52.

Disrupted after-death services were ultimately presented as inauthentic and improper, with implications for their ability to console the bereaved.

Grieving alone

Articles reported how bereaved people were ‘forced’ to grieve alone due to social distancing, travel restrictions and self-isolation. While isolation was described explicitly, its incongruity in most cultural conceptions of ‘normal grief’ was mainly implied. Much like a COVID-19 death, COVID-related grief was portrayed as unnatural and unprecedented. Bereaved people were described as feeling unprepared and lost without the usual rituals and customs surrounding death:

‘“[I am] completely alone. Where do I begin”’. S.A.17.

Grieving alone was portrayed as the final injustice in a tragic situation; one article quoted a bereaved wife’s social media post:

‘“And now I start another complete quarantine, and think what kind of funeral can plan from home, knowing it might not take place for quite a while and might be a lot less that I think he deserves. More travesty!”’ S.A.13.

Those supporting bereaved people were reported to be suffering a sense of helplessness over the lack of usual ritual:

‘“you can’t go to the house and tell them it’s going to be all right”’ Dma.B.43.

As with adaptations to end-of-life care, alternatives to physical contact were typically seen as poor substitutes when offering comfort:

‘“I can’t see my dad, I have got him on the phone, and my brothers and sisters”’ Dmi.B.25.

Discussion

Main findings

In spring 2020, UK newspapers portrayed COVID-19 as profoundly disruptive to the inherently important acts of ‘saying goodbye’ before and after death. Medical institutions were depicted as controlling bedside access, which was variable, uncertain and dependent on the kindness and flexibility of staff. Articles described adapted goodbye rituals via videolinks, but there was ambivalence regarding their acceptability and sufficiency. Similarly, being physically absent at a death was portrayed as distressing for the bereaved, regardless of whether a clinician was present. The media discourse around ‘saying goodbye’ assumed a normative view about what dying and grief should be like, which does not reflect the diversity in people’s experiences and expectations both before and during the pandemic.

COVID-19 was represented homogeneously as unnatural, unprecedented and in conflict with assumed cultural understandings of a ‘good death’ and ‘good grief’. Newspapers focused on the tragedy of what was missing (lack of familial access, dying and grieving alone, restricted funerals), rather than what was permitted. Infection control restrictions and discrepancies in visitation and funeral policies were portrayed as unfair, with the injustice compounded by the unexpectedness of death and problems accessing PPE and virus testing.

Limitations

Study strengths include the variety of newspapers analysed; clearly defined time-frames for comparison, contextualised with other events; and the iterative, team-based and reflexive analysis. We limited our analysis to UK online news media over 2 week-long periods and the concept of ‘saying goodbye’. The methods used capture what was said about the topics at this specific time. 26 Since media narratives evolve and shift over time, findings may not be wholly applicable to other settings or time periods; however, understanding media discourse as reflecting and shaping cultural views on death and grief extends beyond this study.

What this study adds

Our analysis demonstrates the media discourses prevalent during the first wave of the pandemic in the UK, furthers our understanding of cultural constructs related to death and dying, and can help make sense of how individuals have subsequently responded to death and grief at this time. The multiple stages and opportunities to ‘say goodbye’ that were reflected in the media discourse align with theorising dying as a social process that occurs over time. The emphasis on particular moments of saying goodbye, for example at the moment of death or via funerals, and how these were disrupted by COVID-19, indicates a strong cultural narrative about the importance of such moments in the dying process.27,28

The media narratives we identified also have implications for experiences of bereavement, since people rely on media narratives to position themselves and make sense of their experiences. 13 This may be particularly so during the first wave of a new global pandemic: all the news sites we included in our analysis saw a monthly increase in the average amount of time adult visitors spent on their sites from December 2019 to March 2020. 29 By emphasising COVID-19-related death and grief as tragic, newspapers engage societal and cultural perspectives regarding ‘good’ and ‘bad’ deaths. 30 Media representations of COVID-19 deaths and grief as inherently ‘bad’ could negatively influence how people grieve. Such representations also assume a homogenous understanding of death and grief, ignoring individual choices 31 and variations in values and perspectives, for example, that some people wish to die alone, 32 or that others may not wish to be present at their relative’s moment of death. 27 The lack of nuance in media reporting thus contradicts the possibility of a ‘good enough’ death in difficult circumstances. 33

Articles commonly suggested that pandemic-related disruptions would have long-term consequences for bereaved people. Ultimately, the impact of these disruptions, as well as the effects of media narratives of COVID-19 deaths and bereavement, is an empirical question. Research is needed (and underway34,35) to investigate bereavement experiences during the pandemic and their long-term effects, to determine how to best support bereaved people. Clearly, many aspects of a COVID-19 death could have a profound impact: for example, being unable to say goodbye or having to do so via videolink, not having the option of being present at the time of death, or being present only for a short time and in full PPE, and having to make difficult decisions regarding the risk of visiting a loved one or attending a funeral.36,37 Social distancing, quarantining and curfews might also affect usual bereavement processes; for example, ‘restoration-oriented’ activities undertaken to help accommodate a loss might be put on hold. 38 Where this is the case, the grieving process might be delayed or more complex, with the bereaved person potentially requiring additional support. Funeral restrictions, often portrayed in the media as a source of shame and guilt, are not necessarily associated with poor bereavement outcomes 39 and online services can have benefits,40,41 however more research in this area is needed.

Although rarely apportioning blame, pervading the articles was a sense of unfairness, injustice and inequity related to widespread reporting of a lack of ventilators and PPE, arguably avoidable deficits. 42 There is evidence that palliative care services were not prioritised when supplies of PPE were constrained, despite the impact on patients and their loved ones: an international survey found 48% of palliative care services reported shortages of PPE. 43 Despite a general lack of reporting on Black and Asian populations during the sampled time period, later reporting described higher death rates amongst Black and Asian patients and healthcare professionals, 44 adding to a sense of unfair, unequal and avoidable loss.

Implications for practice

Our research was conducted in the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK, and as many countries continue to face additional waves of the pandemic, these findings are particularly pertinent for the clinical practice of end-of-life care globally. Implications of the findings for clinicians, policy makers and journalists are summarised here and presented in Box 1. First, health and social care professionals should recognise the impact of these media narratives on patients’ and families’ fears and anxieties. Second, because the media portrayal of goodbyes via videolink, or with clinicians in the place of loved ones, suggests such goodbyes are culturally insufficient, videolinks should be used cautiously, following an individualised approach, and bedside access granted to loved ones wherever possible. Third, clinicians should understand the importance of each stage of a ‘goodbye’, and public health messaging should promote important conversations between loved ones prior to serious illness.45,46 Fourth, families must be signposted to bereavement services and supported after a death. Fifth, health and social care staff can engage with the media and the public to share their stories and present an alternative narrative. Finally, journalists could better support the public and bereaved people by providing diverse narratives and practical guidance.

Box 1.

Study implications for clinicians, policy makers and journalists.

| Implications | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Avoid assuming that a COVID-19 death is inherently bad or worse than a typical death | Since media narratives affect the public, people’s fears, concerns and anxieties are likely to arise from media messaging. Negativity and lack of nuance were found in a study of media coverage of remote medical consultations during the pandemic 47 ; we found similar features in coverage of death and bereavement. The lack of positive advice for those affected, or examples of a ‘good enough’ death, may further stoke anxieties and reduce health-seeking behaviours. Avoiding assumptions that a COVID-19 death is ‘bad’ or ‘worse’ than a ‘typical’ death may be more supportive than following the common media narrative. |

| Use videolinks with caution and prioritise bedside access | Media portrayals demonstrate the strength of specific cultural concepts of a ‘good death’ and ‘good grief’. Whilst there is no single culturally accepted notion of ‘good death’ in the UK, 48 end-of-life care policy focuses on a particular set of attributes, 49 one of which is not dying alone. Adapted ways of saying goodbye, such as the use of videolinks or clinicians being present instead of loved ones, were generally portrayed as unnatural and insufficient. Recognising the power of these cultural narratives requires a cautious and individualised approach to the use of video-links at the end of life,50,11 and prioritising PPE availability in end-of-life care to enable in-person bedside access where possible. |

| Understand the importance of each stage of ‘goodbye’ | We identified three stages of ‘saying goodbye’ (prior to, at the moment of, and after death). The importance of each stage will vary for everyone, reflecting feelings, preferences and cultural and religious values. The ability to say goodbye in a preferred manner is correlated with better social adjustment 51 in bereavement; however, where someone’s wishes cannot be met due to infection control restrictions, a meaningful goodbye might still be possible. Findings from Japan suggest meaningful communication, rather than physical presence, improves outcomes for bereaved people. 52 Clinicians will ideally understand the relative importance of each stage of saying goodbye for individual patients and families. Public health messaging to encourage Advance Care Planning or ‘What Matters Most’ conversations prior to serious illness can help patients, families and their care teams to work towards a life and death which is in line with patients’ and families’ wishes and values and ensure important conversations aren’t missed.45,46 |

| Signpost families to bereavement services and provide support after a death | The unnaturalness and profound distress evident in media portrayals highlights the importance of signposting to bereavement services and proactively identifying and supporting those at particular risk of poor outcomes.4,53 Cumulative disrupted goodbyes may mean bereaved people require extra support, particularly in understanding how these missed opportunities affect their grieving process. Articles indicated that bereaved people may experience guilt and shame; professionals should be mindful that the choices bereaved people had to make may have ongoing mental health implications. Emerging evidence suggests more support is needed: a national survey (n = 532) found that 36% of bereaved people felt not at all supported by healthcare professionals immediately after the death and 51% were not provided with any information about bereavement support. 35 |

| Health and social care staff can engage with the media and the public to share their stories and present an alternative narrative | Health and social care professionals and those working in bereavement services, supported by press offices where available, can play an important role in communicating with the media, engaging in public discourse and, crucially, offering the public an alternative narrative about healthcare, death and bereavement in the context of COVID-19. Many clinicians have taken on such a role during the pandemic, to great effect. 54 Social media can be a useful way to share stories, influence debates and contribute expertise, however clinicians should know social media posts might be printed in the media. Professional guidance exists to support healthcare staff. 55 |

| Journalists could support the public and bereaved people by providing diverse narratives and practical guidance | We found little nuance in how end-of-life and bereavement experiences were portrayed, and little practical or useful guidance, for example, regarding what support might be available or what kind of funeral service might be possible. Newspaper reportage could raise awareness of the dying process, showcase a wider range of experiences of grief, and provide support to bereaved people. By providing diverse narratives and practical guidance, journalists could play an important supportive role. |

Conclusions

At the beginning of the pandemic, online UK newspapers represented COVID-19 as disrupting culturally expected rituals of ‘saying goodbye’ before, during and after death. Adaptations were presented as insufficient attempts to ameliorate tragic situations. Understanding the media representations and cultural narratives around a ‘good death’ and ‘good grief’ that influence patients’ and families’ fears and anxieties can help inform person-centred care and bereavement support. Health and social care professionals and other bereavement support providers should take into account the potential effect of media reporting on people’s fears and bereavement, and explore ways of finding meaningful connection despite restrictions. They can also play an important role in offering alternative narratives and engaging with the media to educate and inform, with support from hospital press officers where available. More could be done in media reporting to portray diverse experiences and offer practical advice to those dealing with serious illness and bereavement during the pandemic.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211017023 for ‘Saying goodbye’ during the COVID-19 pandemic: A document analysis of online newspapers with implications for end of life care by Lucy E Selman, Ryann Sowden and Erica Borgstrom in Palliative Medicine

Footnotes

Authorship: LS and RS conceived the study. LS, RS and EB designed the study protocol. RS analysed the data, with input and supervision from LS and EB. All authors contributed to drafting the paper, revised the paper and approved the final version. LS oversaw data collection, analysis and reporting and is the guarantor.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: LS and RS are funded by a Career Development Fellowship from the National Institute for Health Research. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethics and consent: This study involved document analysis of published media so did not require approval of an ethics committee or consent of participants.

ORCID iDs: Lucy E Selman  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5747-2699

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5747-2699

Erica Borgstrom  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1009-2928

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1009-2928

Data management and sharing: All relevant data are available in figshare:10.6084/m9.figshare.14074547.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard, https://covid19.who.int/ (2021, accessed 11 February 2021).

- 2. Verdery AM, Smith-Greenaway E, Margolis R, et al. Tracking the reach of COVID-19 kin loss with a bereavement multiplier applied to the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020; 117: 17695–17701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mayhew F. Covid-19 prompts record digital audience for UK national press with 6.6m extra daily readers. Press Gazette, 17 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Selman LE, Chao D, Sowden R, et al. Bereavement support on the frontline of COVID-19: recommendations for hospital clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 60: e81–e86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eisma MC, Tamminga A, Smid GE, et al. Acute grief after deaths due to COVID-19, natural causes and unnatural causes: an empirical comparison. J Affect Disord 2021; 278: 54–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kentish-Barnes N, Chaize M, Seegers V, et al. Complicated grief after death of a relative in the intensive care unit. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Probst DR, Gustin JL, Goodman LF, et al. ICU versus non-ICU hospital death: family member complicated grief, posttraumatic stress, and depressive symptoms. J Palliat Med 2016; 19: 387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lobb EA, Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM, et al. Predictors of complicated grief: a systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud 2010; 34: 673–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Molina N, Viola M, Rogers M, et al. Suicidal ideation in bereavement: a systematic review. Behav Sci 2019; 9: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burrell A, Selman LE. How do funeral practices impact bereaved relatives’ mental health, grief and bereavement? A mixed methods review with implications for COVID-19. Omega. Epub ahead of print 8 July 2020. DOI: 10.1177/0030222820941296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fusi-Schmidhauser T, Preston NJ, Keller N, et al. Conservative management of Covid-19 patients – emergency palliative care in action. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 60: 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Brussel L, Carpentier N. The discursive construction of the good death and the dying person: a discourse-theoretical analysis of Belgian newspaper articles on medical end-of-life decision making. J Lang Polit 2012; 11: 479–499. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seale C. Constructing death: the sociology of dying and bereavement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hanusch F. Representing death in the news: journalism, media and mortality. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wodak R, Meyer M. Critical discourse analysis: history, agenda, theory and methodology. In: Wodak R, Meyer M. (eds) Methods of critical discourse studies. 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2015, pp.1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson MNP, McLean E. Discourse analysis. In: Kobayashi A. (ed.) International encyclopedia of human geography. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier, 2020, pp.377–383. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walter T. What is complicated grief? A social constructionist perspective. Omega 2006; 52: 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reimers E. A reasonable grief – discursive constructions of grief in a public conversation on raising the shipwrecked M/S Estonia. Mortality 2003; 8: 325–341. [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCarthy JR, Evans R, Bowlby S. Diversity challenges from urban West Africa: how Senegalese family deaths illuminate dominant understandings of ‘bereavement’. Bereave Care 2019; 38: 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sowden R, Borgstrom E, Selman LE. ‘It’s like being in a war with an invisible enemy’: a document analysis of bereavement due to COVID-19 in UK newspapers. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0247904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ofcom. News consumption in the UK: 2019 report. 24 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hilton S, Hunt K, Langan M, et al. Newsprint media representations of the introduction of the HPV vaccination programme for cervical cancer prevention in the UK (2005-2008). Soc Sci Med 2010; 70: 942–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Altheide DL. Tracking discourse and qualitative document analysis. Poetics 2000; 27: 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hart B, Sainsbury P, Short S. Whose dying? A sociological critique of the ‘good death’. Mortality 1998; 3: 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mogashoa T. Understanding critical discourse analysis in qualitative research. Int J Humanit Soc Sci Educ 2014; 1: 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lasswell HD, Lerner D, Pool IdS. Comparative study of symbols: an introduction. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Valentine C. The “Moment of Death”. Omega 2007; 55: 219–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoy WG. Do funerals matter?: the purposes and practices of death rituals in global perspective. New York, NY: Routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ofcom. Effects of Covid-19 on online consumption. 7 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Green JW. Beyond the good death: the anthropology of modern dying. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Borgstrom E. How COVID-19 challenges our notion of a good death, https://discoversociety.org/2020/04/12/how-covid-19-challenges-our-notions-of-a-good-death/ (2020, accessed 29 September 2020).

- 32. Caswell G, O’Connor M. ‘I’ve no fear of dying alone’: exploring perspectives on living and dying alone. Mortality 2019; 24: 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 33. McNamara B. Good enough death: autonomy and choice in Australian palliative care. Soc Sci Med 2004; 58: 929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Covid Bereavement. Grief experience and support needs of people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic, https://www.covidbereavement.com/ (2020, accessed 14 January 2021).

- 35. Harrop E, Farnell D, Longo M, et al. Supporting people bereaved during COVID-19: study report 1. Report, Cardiff University and the University of Bristol, 27 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wallace CL, Wladkowski SP, Gibson A, et al. Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 60: e70–e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eisma MC, Boelen PA, Lenferink LI. Prolonged grief disorder following the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychiatry Res 2020; 288: 113031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: a decade on. Omega 2010; 61: 273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Selman L, Burrell A. The effect of funeral practices on bereaved friends and relatives’ mental health and bereavement: implications for COVID-19. Report, University of Bristol, UK, May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bear L, Simpson N, Angland M, et al. ‘A good death’ during the Covid-19 pandemic in the UK: a report of key findings and recommendations. London: LSE Anthropology, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wood P. Lockdown-era Zoom funerals are upending religion traditions – and they may change the way we grieve forever, https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/philosophy/funerals-during-lockdown-coronavirus-covid-religious-tradition-zoom-grief (2020, accessed 12 November 2020).

- 42. Peterson A, Largent EA, Karlawish J. Ethics of reallocating ventilators in the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020; 369: m1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oluyase AO, Hocaoglu M, Cripps RL, et al. The challenges of caring for people dying from COVID-19: a multinational, observational study (CovPall). J Pain Symptom Manage. Epub ahead of print 5 February 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.01.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Iacobucci G. Covid-19: deprived areas have the highest death rates in England and Wales. BMJ 2020; 369; m1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. EOLC Partners Think Tank. What matters conversations, https://www.whatmattersconversations.org/ (2020, accessed 14 January 2021).

- 46. Selman L, Lapwood S, Jones N, et al. What enables or hinders people in the community to make or update advance care plans in the context of Covid-19, and how can those working in health and social care best support this process? Oxford: The Centre for Evidence Based Medicine, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mroz G, Papoutsi C, Rushforth A, et al. Changing media depictions of remote consulting in COVID-19: analysis of UK newspapers. Br J Gen Pract 2020; 71: e1–e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cottrell L, Duggleby W. The “good death”: an integrative literature review. Palliat Support Care 2016; 14: 686–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Borgstrom E. What is a good death? A critical discourse policy analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020; Epub ahead of print 6 July 2020. DOI: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pattison N. End-of-life decisions and care in the midst of a global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2020; 58: 102862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kissane DW, Bloch S, McKenzie DP. Family coping and bereavement outcome. Palliat Med 1997; 11: 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Otani H, Yoshida S, Morita T, et al. Meaningful communication before death, but not present at the time of death itself, is associated with better outcomes on measures of depression and complicated grief among bereaved family members of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 54: 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Harrop E, Mann M, Semedo L, et al. What elements of a systems’ approach to bereavement are most effective in times of mass bereavement? A narrative systematic review with lessons for COVID-19. Palliat Med 2020; 34: 1165–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Clarke R. Breathtaking: inside the NHS in a time of pandemic. London: Little, Brown Book Group, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 55. British Medical Association. Social media, ethics and professionalism: BMA guidance. London: British Medical Association, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211017023 for ‘Saying goodbye’ during the COVID-19 pandemic: A document analysis of online newspapers with implications for end of life care by Lucy E Selman, Ryann Sowden and Erica Borgstrom in Palliative Medicine