Abstract

Background

Care home residents have complex healthcare needs but may have faced barriers to accessing hospital treatment during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objectives

To examine trends in the number of hospital admissions for care home residents during the first months of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of a national linked dataset on hospital admissions for residential and nursing home residents in England (257,843 residents, 45% in nursing homes) between 20 January 2020 and 28 June 2020, compared to admissions during the corresponding period in 2019 (252,432 residents, 45% in nursing homes). Elective and emergency admission rates, normalised to the time spent in care homes across all residents, were derived across the first three months of the pandemic between 1 March and 31 May 2020 and primary admission reasons for this period were compared across years.

Results

Hospital admission rates rapidly declined during early March 2020 and remained substantially lower than in 2019 until the end of June. Between March and May, 2,960 admissions from residential homes (16.2%) and 3,295 admissions from nursing homes (23.7%) were for suspected or confirmed COVID-19. Rates of other emergency admissions decreased by 36% for residential and by 38% for nursing home residents (13,191 fewer admissions in total). Emergency admissions for acute coronary syndromes fell by 43% and 29% (105 fewer admission) and emergency admissions for stroke fell by 17% and 25% (128 fewer admissions) for residential and nursing home residents, respectively. Elective admission rates declined by 64% for residential and by 61% for nursing home residents (3,762 fewer admissions).

Conclusions

This is the first study showing that care home residents’ hospital use declined during the first wave of COVID-19, potentially resulting in substantial unmet health need that will need to be addressed alongside ongoing pressures from COVID-19.

Keywords: hospital admissions, care homes, COVID-19, linked data, administrative data

Highlights

The NHS in England rapidly reorganised and reprioritised the delivery of hospital care at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

There was a substantial and sustained decline in hospital admissions from care homes during the first months of the pandemic.

The proportion of emergency admissions that were potentially avoidable was broadly similar to the previous year.

The decrease in admissions may be indicative of substantial unmet healthcare need in residential care settings.

Further research is needed to understand health outcomes for residents who required urgent care during this period.

Background

Worldwide the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in substantial excess mortality among people living in care homes [1]. Excess deaths have been attributed directly to viral infection, and to increases in deaths due to other causes, most commonly diabetes, heart diseases, Alzheimer’s and dementia, and cerebrovascular diseases [2–4]. In England, there are two main types of care homes: residential care homes, which provide accommodation and help with personal care (such as washing, dressing and taking medication), and nursing homes, which additionally provide 24-hour support from qualified nurses. There are differences in resident characteristics between the two care home types, with a higher proportion of nursing home residents being in their last year of life [5, 6]. Multimorbidity, functional dependence and cognitive impairments are highly prevalent in both populations, resulting in complex healthcare needs [5, 7, 8].

In response to the pandemic, the English National Health Service (NHS) rapidly reorganised and reprioritised the delivery of care in March 2020. Non-urgent elective care was paused [9], and there were substantial drops in attendance for emergency care among the general public [10]. Local health systems were asked to provide enhanced primary and community care services to residents of care homes, intended to reduce reliance on acute hospital care [11]. Measures included personalised care and support plans for residents, and patient reviews during remote weekly ‘check ins’ [12].

Following concerns about inappropriate uses of advance care plans and do not attempt resuscitation orders early in the pandemic, the regulator issued a clarification stating that hospitals should enable equal access for care home residents to urgent hospital care and treatment for COVID-19 [13, 14]. However, governance and effectiveness of joint working arrangements varied between local systems and some care homes reported difficulties in accessing urgent general practice and hospital care [15, 16]. The risk of acquiring COVID-19 infection in hospital may also have led to changes in patient and carer preferences and care seeking behaviour [17].

While there is evidence that older people might have been disproportionately affected by disruptions to hospital care [18], there is currently only preliminary evidence for a decrease in hospital admissions for people living in care homes in England [19]. There remains a need to better understand the impact of the pandemic on residents’ health status and quality of life and to plan for the capacity required to address unmet care need. However, these efforts have been hampered by the lack of a central register of care home residents and the challenge to identify residents in national, routinely collected healthcare data [20]. We therefore used an address-based linkage methodology to examine national trends in elective and emergency hospital admissions for individuals living in residential and nursing homes in England, as well as changes in the primary reasons for admissions during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Methods

Data sources

We used administrative data on hospital admissions from Secondary Uses Service, a national database of NHS-funded hospital activity in England. As care homes are not reliably recorded as admission source, care home residents were identified through linkage to the patient index from the National Health Applications and Infrastructure Services, as previously described [5, 7]. This database contains longitudinal records of patient registrations with general practices in England, including patient address and year and month of death. Data extracts are created on the first Sunday following the 13th day of the month. Patient addresses were matched to Unique Property Reference Numbers and subsequently cross-referenced to care home addresses and characteristics held by the Care Quality Commission, the regulator of social care services in England. Care home opening and closing dates were used to resolve address matches to multiple care homes, which can occur when recorded characteristics of care homes change. Small area-level socioeconomic deprivation (Index of Multiple Deprivation 2019, Office for National Statistics) was added using care home Lower Layer Super Output Areas (LSOA). All processing of addresses and linkage of patient information was carried out by the National Commissioning Data Repository. Data were anonymised in line with the Information Commissioner’s Office’s code of practice on anonymisation.

Study populations

Individuals were included in the 2020 study cohort if they were recorded as living in a care home on 19 January 2020. These were compared to a cohort of individuals living in a care home on 20 January 2019. Residents of all ages and in all types of care homes were included, including specialist care homes. The cohorts were further split into subgroups based on care home type (residential or nursing) using information provided by the regulator that nursing care was being provided to some residents.

Patient characteristics

Age, sex, and month of death were taken from the patient index. The Charlson Comorbidity Index and previous dementia diagnoses for each resident were determined using primary and secondary diagnosis codes of all hospital admissions from up to three years prior to the respective study start date in January [21–23].

Hospital admissions

The follow-up period for the study was between 21 January and 30 June 2019 or between 20 January and 28 June 2020, respectively. Observations were censored at the date of death, or the end of the care home stay. The end of the care home stay was defined as the last day of the monthly data extract where an individual’s address matched to a care home. The date of death was defined as the last day of the month of death, or the last day of the data extract ending in the month of death, whichever was later.

Hospital admissions were not included if the administrative category was private patient, the admission method was a transfer or missing. Admissions were divided into emergency and elective admissions based on the method of admission. Admission rates resident per year or per 100 residents per year were calculated across all residents, controlling for the number of days spent in a care home. Primary admission reasons were categorised according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) chapter of the primary diagnosis code (Appendix Table S1).

Several acute conditions, as defined by ICD-10 code, were selected for further analysis: suspected or confirmed COVID-19 (U07.1, U07.2) [24], acute coronary syndromes (I20.0, I21.0-4, I21.9, I22.0-2, I22.8-9, I24.8-9) [25], and stroke (I61, I63, I64) [26]. A small number of COVID-19 admissions (n = 37, 0.59% of COVID-19 admissions) were coded as elective; these were not analysed separately. Cataract surgeries were defined using Office of Population Censuses Surveys Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures (OPCS4) codes C71-C75 [27], based on all procedure codes for any given admission.

We also examined a subset of unplanned hospital admissions from care homes, which have been referred to as potentially avoidable emergency admissions: either because they are generally considered manageable, treatable or preventable outside a hospital setting or because they can be caused by poor care or neglect [28, 29]. Potentially avoidable emergency admissions have previously been used as primary outcome measure to evaluate the impact of several initiatives to improve health and care in care homes in England [5, 7]. This list of conditions, which was developed by the health and social care regulator, includes acute and chronic lower respiratory tract infections, pressure sores, diabetes, food and drink issues, food and liquid pneumonitis, fractures and sprains, intestinal infections, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections. ICD-10 code lists are shown in Appendix Table S2, including corrections made after consultation with the authors [29].

Although these admissions are not necessarily inappropriate and often cannot be avoided once the condition becomes acute, they may have been preventable at an earlier stage with additional support or better care coordination [5]. The degree to which potentially avoidable admissions could in fact have been avoided will also be influenced by residents’ other health conditions as well as organisational context. Nursing support available in a nursing home may enable staff to oversee treatments that might otherwise require an admission to hospital. However, enhanced primary and community care for care home residents during the COVID-19 outbreak could be expected to have an impact on this group of admissions. Due to the heterogeneity within this group of potentially avoidable admission reasons, we also considered them separately to examine changes in the number of admissions during the pandemic.

Statistical analyses

In Figure 1 showing trends in weekly admission rates, a locally estimated smoothing function was fitted for each group (using the geom_smooth function of the R package ggplot2 and the default loess smoothing function). To assess the similarity between years of baseline characteristics of study cohorts and of admitted patients, absolute standardised mean differences were calculated using the R package tableone. They are defined as the difference in means of a given characteristic as a percentage of the pooled standard deviation, with a cut-off value of 10% being widely adopted for negligible imbalance between groups [30]. Standardised mean differences allow comparisons of the magnitude of difference between groups, rather than statistical significance. They can be used across variables of different scales and have the advantage that they are not dependent on sample size. We used R (version 3.6.3) for data processing and analysis and SAS (version 7.12) for data cleaning and analysis of comorbidities [31].

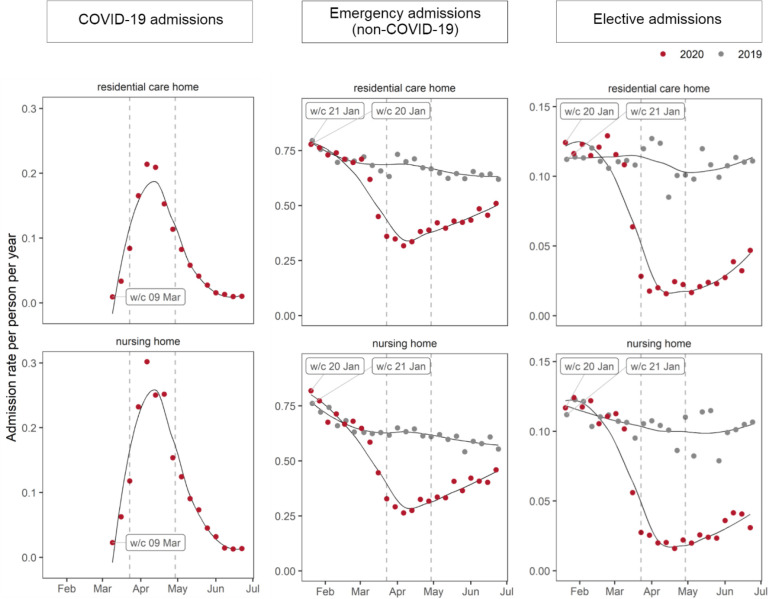

Figure 1: Weekly hospital admission rates of care home residents to National Health Service trusts in England, by care home type and admission type.

A locally estimated smoothing spline was fitted to the weekly admission rates for 2019 and 2020. The date of the UK-wide COVID-19 lockdown (23 March 2020) and the date on which NHS providers were asked to resume elective activity (29 April 2020) are shown as vertical dashed lines. Elective admissions include ordinary admissions and day cases. Emergency admissions (non-COVID-19) are defined as admissions that had a primary diagnosis code other than confirmed or suspected COVID-19. COVID-19 admissions are only shown for weeks where there were more than 10 admissions from both types of care home. w/c; week commencing.

Results

Study populations

We identified 252,432 residents living in a care home in January 2019 and 257,843 residents in January 2020 (45% in nursing homes in both years) who met the inclusion criteria. A data cleaning flow chart is shown in Appendix Figure S1. The demographic characteristics of individuals living in residential and nursing homes were broadly similar in January 2019 and 2020, but mortality during the follow-up period was higher in 2020 (Appendix Table S3 and Appendix Figure S2).

Trends in hospital admissions

To examine trends in hospital admissions, we quantified weekly rates of COVID-19 admissions, other emergency admissions and elective admissions between 20 January 2020 and 28 June 2020 and compared these with the corresponding period in 2019 (Figure 1). For each type of admission, as well as for categories of primary admission reasons, we subsequently compared the number of admissions during the first three months of the COVID-19 outbreak in England, between 1 March and 31 May 2020, with the same period in 2019. This period was chosen as it corresponded to the first wave of the pandemic in care homes (COVID-19 admissions in Figure 1).

A locally estimated smoothing spline was fitted to the weekly admission rates for 2019 and 2020. The date of the UK-wide COVID-19 lockdown (23 March 2020) and the date on which NHS providers were asked to resume elective activity (29 April 2020) are shown as vertical dashed lines. Elective admissions include ordinary admissions and day cases. Emergency admissions (non-COVID-19) are defined as admissions that had a primary diagnosis code other than confirmed or suspected COVID-19. COVID-19 admissions are only shown for weeks where there were more than 10 admissions from both types of care home. w/c; week commencing.

COVID-19 hospital admissions

Weekly COVID-19 admission rates rose sharply from the week commencing 9 March 2020 until mid-April, followed by a decline throughout May 2020 (Figure 1). Between 1 March and 31 May, 2,960 admissions from residential homes and 3,295 admissions from nursing homes were for suspected or confirmed COVID-19 (Table 1), corresponding to 16.2% and 23.7% of all admissions, respectively. COVID-19 admission had a large number of additional diagnosis codes (88% and 87% of admissions from residential and nursing homes, respectively, had 10 or more additional codes) from a wide range of ICD-10 chapters (Appendix Figure S3 and S4). A small proportion of COVID-19 admissions had additional diagnoses for acute events, such as acute coronary syndromes (1.3%) and stroke (0.5%, Appendix Table S4).

Table 1: Characteristics of residents from residential and nursing homes admitted to National Health Service hospital trusts in England, by primary diagnosis (1 March to 31 May 2019, and 1 March to 31 May 2020).

| Care home type | Residential | Nursing | ||||||

| Year | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | ||||

| Primary diagnosis | All | COVID-19 | Other | All | COVID-19 | Other | ||

| N | 24995 | 2960 | 15348 | 17903 | 3295 | 10597 | ||

| Female (%) | 15410 (61.7) | 1609 (54.4) | 9380 (61.1) | 9956 (55.6) | 1604 (48.7) | 5712 (53.9) | ||

| Age in years* | 81 (15) | 83 (11) | 81 (15) | 79 (14) | 79 (12) | 79 (14) | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index* | 2.03 (1.93) | 2.11 (1.89) | 2.09 (1.95) | 2.30 (2.03) | 2.29 (2.01) | 2.35 (2.06) | ||

| Dementia (%) | 12103 (48.4) | 1618 (54.7) | 7774 (50.7) | 8860 (49.5) | 1768 (53.7) | 5389 (50.9) | ||

| IMD quintile†(%) | ||||||||

| 1 (least deprived) | 4783 (19.1) | 615 (20.8) | 2990 (19.5) | 4165 (23.3) | 891 (27.0) | 2456 (23.2) | ||

| 2 | 5423 (21.7) | 664 (22.4) | 3405 (22.2) | 3589 (20.0) | 762 (23.1) | 2105 (19.9) | ||

| 3 | 5533 (22.1) | 659 (22.3) | 3343 (21.8) | 3721 (20.8) | 605 (18.4) | 2227 (21.0) | ||

| 4 | 5016 (20.1) | 609 (20.6) | 3133 (20.4) | 3477 (19.4) | 597 (18.1) | 1986 (18.7) | ||

| 5 (most deprived) | 4162 (16.7) | 403 (13.6) | 2443 (15.9) | 2888 (16.1) | 429 (13.0) | 1799 (17.0) | ||

| Missing | 78 (0.3) | 10 (0.3) | 34 (0.2) | 63 (0.4) | 11 (0.3) | 24 (0.2) | ||

| Region (%) | ||||||||

| East Midlands | 1260 (5.0) | 161 (5.4) | 763 (5.0) | 1324 (7.4) | 255 (7.7) | 886 (8.4) | ||

| East of England | 2659 (10.6) | 313 (10.6) | 1617 (10.5) | 1698 (9.5) | 324 (9.8) | 922 (8.7) | ||

| London | 2951 (11.8) | 419 (14.2) | 1811 (11.8) | 2016 (11.3) | 439 (13.3) | 1116 (10.5) | ||

| North East | 3488 (14.0) | 418 (14.1) | 2032 (13.2) | 2803 (15.7) | 553 (16.8) | 1604 (15.1) | ||

| North West | 2541 (10.2) | 127 (4.3) | 1717 (11.2) | 1547 (8.6) | 132 (4.0) | 954 (9.0) | ||

| South East | 2696 (10.8) | 295 (10.0) | 1662 (10.8) | 1688 (9.4) | 245 (7.4) | 1066 (10.1) | ||

| South West | 3747 (15.0) | 530 (17.9) | 2385 (15.5) | 1746 (9.8) | 362 (11.0) | 1130 (10.7) | ||

| West Midlands | 1718 (6.9) | 378 (12.8) | 868 (5.7) | 2163 (12.1) | 536 (16.3) | 1060 (10.0) | ||

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 3857 (15.4) | 309 (10.4) | 2459 (16.0) | 2855 (15.9) | 438 (13.3) | 1835 (17.3) | ||

| Missing | 78 (0.3) | 10 (0.3) | 34 (0.2) | 63 (0.4) | 11 (0.3) | 24 (0.2) | ||

| Bed capacity* | 37 (20) | 44 (22) | 38 (21) | 61 (27) | 65 (28) | 61 (27) | ||

Admissions include ordinary elective admissions, elective day cases and emergency admissions. *Mean (standard deviation), †Index of Multiple Deprivation quintiles.

By the end of May 2020, 1.9% of the residential cohort and 2.6% of the nursing home cohort had been admitted to hospital at least once for suspected or confirmed COVID-19 (2,716 and 3,051 residents, respectively). When additionally including admissions where COVID-19 was recorded but was not the primary diagnosis, this increased to 2.7% and 3.4% of the residential and nursing home cohort (3,794 and 3,980 residents), respectively.

Residents admitted for COVID-19 were less likely to be female, lived in larger care homes and were more likely to live in London and the West Midlands, compared to residents admitted for other reasons (Table 1 and Appendix Figure S5). A previous diagnosis of dementia was more common among care home residents admitted for COVID-19 than among those admitted to hospital for other reasons. For nursing home residents, COVID-19 admissions (as compared to non-COVID-19 admissions) were more concentrated in less deprived areas and for residential care homes, residents admitted for COVID-19 were older.

Non-COVID-19 emergency admissions

The rates of emergency admissions with primary diagnoses other than COVID-19 decreased by over a third during the first three months of the outbreak compared to the same period in 2019, with a 36% decrease for residential (7,420 fewer admissions) and 38% decrease for nursing home residents (5,771 fewer admissions, Table 2).

Table 2: Number of hospital admissions and hospital admission rates of care home residents to National Health Service trusts in England between 1 March and 31 May in 2019 and 2020, by care home type and admission type 9pt11pt.

| Care home type | Residential | Nursing | |||||

| 2019 | 2020 | Change (%) | 2019 | 2020 | Change (%) | ||

| Elective* | |||||||

| N | 3493 | 1266 | -2227 (-64) | 2511 | 976 | -1535 (-61) | |

| Rate† | 10.92 | 3.90 | -7.03 (-64) | 10.12 | 3.91 | -6.22 (-61) | |

| Emergency, all | |||||||

| N | 21502 | 17042 | -4460 (-21) | 15392 | 12916 | -2476 (-16) | |

| Rate† | 67.22 | 52.43 | -14.79 (-22) | 62.06 | 51.68 | -10.38 (-17) | |

| Emergency, COVID-19 | |||||||

| N | - | 2960 | - | - | 3295 | - | |

| Rate† | - | 9.11 | - | - | 13.18 | - | |

| Emergency, other primary diagnosis | |||||||

| N | 21502 | 14082 | -7420 (-35) | 15392 | 9621 | -5771 (-37) | |

| Rate† | 67.22 | 43.33 | -23.9 (-36) | 62.06 | 38.50 | -23.56 (-38) | |

| Emergency, potentially avoidable | |||||||

| N | 7652 | 4926 | -2726 (-36) | 6052 | 3755 | -2297 (-38) | |

| Rate† | 23.92 | 15.16 | -8.77 (-37) | 24.40 | 15.03 | -9.38 (-38) | |

*Includes ordinary admissions and day cases. †Admissions per 100 residents per year.

The magnitude of change varied between admissions associated with different ICD-10 diagnosis chapters, with the largest decline seen in infectious and parasitic diseases and diseases of the blood, and the smallest decline for injuries and poisonings (Appendix Table S5). Admission rates for acute coronary syndromes fell by 43% and 29% and admissions for stroke fell by 17% and 25% for residents from residential and nursing homes, respectively (Appendix Table S6).

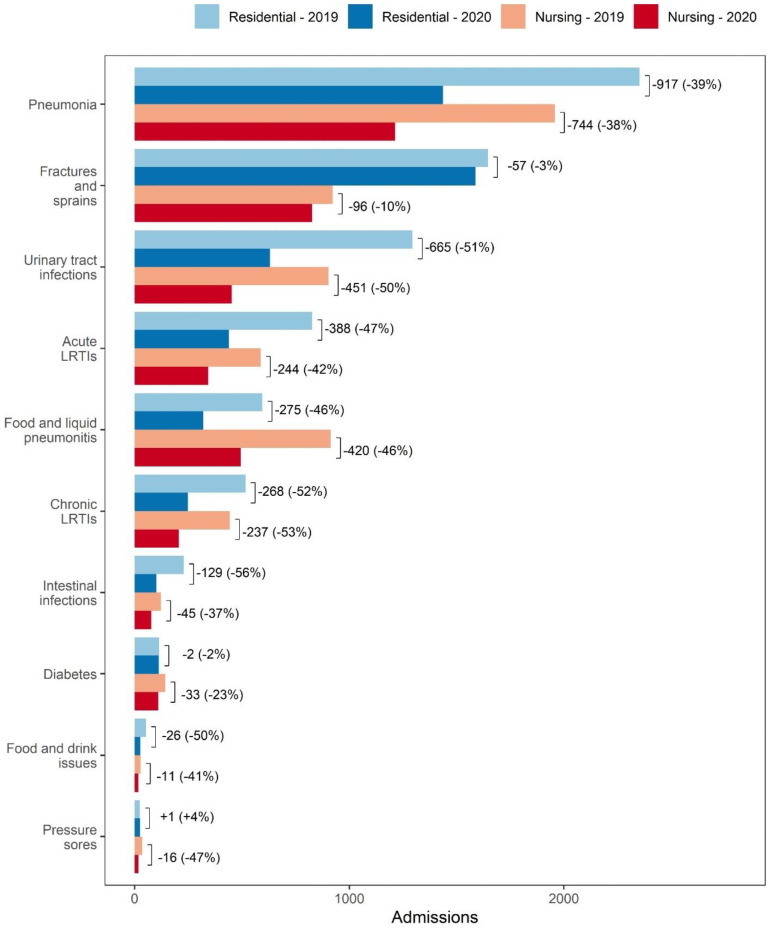

The overall proportion of (non-COVID-19) emergency admissions that occurred for potentially avoidable reasons within this period were similar in both years, at around 35% of (non-COVID-19) emergency admissions from residential care homes and 39% of admissions from nursing homes (Table 2). Admissions for urinary tract infections (UTI) fell by half in 2020 compared to 2019 for both residential (665 fewer admissions) and nursing home residents (451 fewer admissions, Figure 2 and Appendix Table S7). Admissions for pneumonia decreased by over a third for both residential (917 fewer admissions) and nursing home residents (744 fewer admissions) but remained the most common potentially avoidable admission reason. The number of admissions for fractures and sprains remained broadly similar for both residential and nursing home residents.

Figure 2: Number of potentially avoidable emergency admissions between 1 March and 31 May in 2019 and 2020, by primary admission reason and care home type.

Bars are labelled to show the absolute and percent difference between 2019 and 2002, by care home type. LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection.

Elective hospital admissions

Compared to the same period in 2019, elective hospital admission rates during the first three months of the pandemic in England decreased by 64% for residential care homes (2,227 fewer admissions) and by 61% for nursing homes (1,535 fewer admissions, Table 2). Both for residential and nursing home residents, there were fewer admissions across all ICD-10 chapters in 2020 compared to 2019 (Table 3).

Table 3: Number of elective admissions (ordinary admissions and day cases) and elective admission rates between 1 March and 31 May in 2019 and 2020, by care home type and ICD-10 chapter of the primary diagnosis code.

| Care home type | Residential | Nursing | ||||||

| 2019 | 2020 | Change (%) | 2019 | 2020 | Change (%) | |||

| ICD-10 chapter | ||||||||

| 7 | Eye, adnexa | |||||||

| N | 600 | 133 | -467 (-78) | 417 | 94 | -323 (-77) | ||

| Rate* | 1.88 | 0.41 | -1.47 (-78) | 1.68 | 0.38 | -1.31 (-78) | ||

| 13 | Musculoskeletal, connective | |||||||

| N | 228 | 55 | -173 (-76) | 140 | 32 | -108 (-77) | ||

| Rate* | 0.71 | 0.17 | -0.54 (-76) | 0.56 | 0.13 | -0.44 (-77) | ||

| 11 | Digestive system | |||||||

| N | 603 | 152 | -451 (-75) | 326 | 91 | -235 (-72) | ||

| Rate* | 1.89 | 0.47 | -1.42 (-75) | 1.31 | 0.36 | -0.95 (-72) | ||

| 6 | Nervous system | |||||||

| N | 99 | 29 | -70 (-71) | 136 | 76 | -60 (-44) | ||

| Rate* | 0.31 | 0.09 | -0.22 (-71) | 0.55 | 0.3 | -0.24 (-45) | ||

| 12 | Skin, subcutaneous tissue | |||||||

| N | 128 | 38 | -90 (-70) | 76 | 40 | -36 (-47) | ||

| Rate* | 0.40 | 0.12 | -0.28 (-71) | 0.31 | 0.16 | -0.15 (-48) | ||

| 14 | Genitourinary system | |||||||

| N | 178 | 57 | -121 (-68) | 221 | 51 | -170 (-77) | ||

| Rate* | 0.56 | 0.18 | -0.38 (-69) | 0.89 | 0.2 | -0.69 (-77) | ||

| 18 | Not elsewhere classified | |||||||

| N | 197 | 77 | -120 (-61) | 143 | 65 | -78 (-55) | ||

| Rate* | 0.62 | 0.24 | -0.38 (-62) | 0.58 | 0.26 | -0.32 (-55) | ||

| 21 | Factors infl. health status | |||||||

| N | 171 | 69 | -102 (-60) | 252 | 96 | -156 (-62) | ||

| Rate* | 0.54 | 0.21 | -0.32 (-60) | 1.02 | 0.38 | -0.63 (-62) | ||

| 19 | Injury, poisoning | |||||||

| N | 88 | 36 | -52 (-59) | 93 | 45 | -48 (-52) | ||

| Rate* | 0.28 | 0.11 | -0.16 (-60) | 0.38 | 0.18 | -0.2 (-52) | ||

| 3 | Blood, blood-forming organs | |||||||

| N | 260 | 107 | -153 (-59) | 117 | 68 | -49 (-42) | ||

| Rate* | 0.81 | 0.33 | -0.48 (-60) | 0.47 | 0.27 | -0.2 (-42) | ||

| 2 | Neoplasms | |||||||

| N | 616 | 304 | -312 (-51) | 428 | 223 | -205 (-48) | ||

| Rate* | 1.93 | 0.94 | -0.99 (-51) | 1.73 | 0.89 | -0.83 (-48) | ||

| 9 | Circulatory system | |||||||

| N | 121 | 64 | -57 (-47) | 75 | 26 | -49 (-65) | ||

| Rate* | 0.38 | 0.2 | -0.18 (-48) | 0.30 | 0.1 | -0.2 (-66) | ||

| 5 | Mental, behavioural | |||||||

| N | 52 | 30 | -22 (-42) | 16 | 13 | -3 (-19) | ||

| Rate* | 0.16 | 0.09 | -0.07 (-44) | 0.07 | 0.05 | -0.01 (-20) | ||

| Other | ||||||||

| N | 111 | 34 | -77 (-69) | 59 | 18 | -41 (-69) | ||

| Rate* | 0.35 | 0.11 | -0.24 (-70) | 0.24 | 0.07 | -0.17 (-70) | ||

| Unknown | ||||||||

| N | 41 | 81 | +40 (+98) | 12 | 38 | +26 (+217) | ||

| Rate* | 0.13 | 0.25 | +0.12 (+95) | 0.05 | 0.15 | +0.1 (+217) | ||

Admissions where the primary diagnosis code corresponded to a chapter that had <10 admissions for at least one year in one care home type were grouped into Other. Rows are sorted by increasing % change in residential care homes. ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision. *Admissions per 100 residents per year.

Among the three most commons ICD-10 chapters (neoplasms, eye conditions, conditions of the digestive system), the largest decrease, both in relative and absolute terms, was seen for admissions for eye conditions (a 78% decline in admission rates in both care settings), corresponding to a total of 790 fewer admissions than in 2019. This was also reflected in the number of hospital admissions with a record of cataract surgeries, which decreased by 81% in both care settings (503 fewer admissions with cataract procedures in total, Appendix Table S8). In contrast, admissions for neoplasms had a smaller percentage decrease (a decrease of 51% and 48% for residential and nursing home residents, respectively), with a total of 517 fewer admissions across both care settings.

Discussion

Principal findings

To free hospital capacity for patients critically ill with COVID-19 and to reduce the risk of infection during the first wave of the pandemic, local health systems and the NHS in England rapidly reorganised care pathways. This led to concerns that care home residents may have faced barriers to accessing hospital care. During the first wave of the pandemic in care homes, between 1 March and 31 May 2020, there were 6,255 admissions for suspected or confirmed COVID-19 from residential care settings, which peaked during the first half of April. Admissions for COVID-19 were skewed towards larger care homes and care homes located in London and the West Midlands. London was the region with the highest levels of SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence in the general population in July 2020 and international evidence strongly suggests that there is a relationship between high community prevalence of COVID-19 and COVID-19-related mortality rate in care homes [32–35]. Compared to the same period in 2019, there were 13,191 fewer emergency admissions for reasons other than COVID-19, a decline of over a third. This was only partially due to a decrease in potentially avoidable conditions, as the proportion of emergency admissions that were potentially avoidable was broadly similar to the previous year. However, we observed substantial changes in the number of admissions for some potentially avoidable reasons, such as UTIs. The most substantial drop was seen for elective admissions, where there were 3,762 fewer admissions from residential care settings than in 2019, a decline of close to two thirds.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. It is based on a novel linkage methodology to identify care home residents in routinely collected hospital data, as care home residents are not consistently flagged in administrative hospital records. With a positive predictive value of over 99% compared to manual address matching, this method allowed us to only include admissions for patients that were highly likely to be genuine care home residents [36]. The study also captures all admissions to NHS hospitals in England. Therefore, it provides the first comprehensive overview over hospital inpatient activity of care home residents in England during the pandemic. Our study has some limitations. A recent validation study showed that, compared to manual address matching, the linkage methodology misses around 22% of care home residents [36]. However, due to the stratified sampling design used in the validation study, it does not allow us to assess whether the linkage quality varies by certain care home characteristics, such as size and rurality. As the linkage method relies on patient addresses held by general practices, we may not capture admissions for residents who moved into a care home around the time of the study start, who moved into a care home on a temporary basis or where the address had not been updated. There might also be variation in how timely patient addresses are updated. Due to these methodological constraints, this study was designed as a cross-sectional analysis of the population of residents who were living in a care home before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with an adjustment for the time spend in a care home. A caveat to extrapolating these findings to the current population of care home residents is therefore that there may have been systemic changes in resident characteristics, due to the uneven impact of COVID-19 mortality across care homes, changes in care home occupancy levels or the influx of new residents [3, 37, 38]. While the study cohorts were comparable in observed characteristics, another limitation of observational studies is that unobserved differences between study cohorts or hospital records could have confounded the estimates. During the early stages of the outbreak, COVID-19 diagnoses might not have been accurately captured in hospital records, and for all admissions the severity of the condition would not be captured in the data. Following a COVID-19 incident in a care home, other residents in the same home may have been less likely to seek hospital treatment for other care needs due to isolation measures. This was not possible to be determined without access to linked data on care home outbreaks. The list of potentially avoidable reasons was developed by the regulator for an analysis focusing on trends in hospital care use by older people but was not specifically designed for care home residents [29]. While it is based on a list of commonly defined ambulatory care sensitive conditions and captures the most common preventable causes of harm in care homes [39], further validation of the individual conditions as a marker of potentially avoidable admissions in the care home population is needed.

Comparison with previous work

The baseline hospital admission rates for our cohort of residents, as well as their relative proportions, are similar to a previous study of care home residents in England aged 65 or over, which reported 0.77 and 0.63 annual emergency admissions per residential and nursing home resident, respectively [7]. The small difference in observed rates might be explained by the different age cutoff and the fact that we used data from March, April and May, rather than data on admissions across a whole year. We also found that there were more COVID-19 admissions from nursing homes than from residential care homes. This is consistent with emerging evidence that care home size is an important risk factor for experiencing a COVID-19 outbreak and nursing homes on average have a greater number of beds [40]. In our study, 2.2% of residents experienced a hospital admission for COVID-19 between 1 March and 31 May 2020. A survey of 9,081 care homes in England between 26 May and 20 June 2020 reported that 11% of residents had tested positive for COVID-19 [41]. Excess mortality attributable to COVID-19 in care homes in England up to 7th August 2020 has been estimated to be equivalent to 6.5% of care home beds [3].

Implications

Our analysis shows that care home residents’ use of inpatient hospital care decreased during the first three months of the pandemic. The largest decreases were observed for elective care and some potentially avoidable admissions, such as urinary tract infections. We saw large variation within the group of conditions associated with potentially avoidable admissions and their changes during the COVID-19 outbreak, compared to the previous year. However, interpreting these differences is complex, as not all conditions within this group will be equally amenable to prevention and treatment in the community. Some acute emergency conditions, including acute coronary syndromes and stroke, also saw decreases admissions, indicating that fewer residents received appropriate urgent hospital care.

These changes are likely to be driven by several factors. Firstly, avoiding hospital admission has previously been seen as preferable by both clinicians and residents [42]. This sentiment may have grown stronger due to the risk of contracting COVID-19 in hospital [17]. Secondly, as previous evidence shows that some avoidable emergency admissions can be reduced through enhanced primary care in care homes [5], the additional support provided by primary and community care teams may have been successful in avoiding some of these during the COVID-19 outbreak [43]. Consistent with the observed variation in the changes of avoidable admission reasons seen in this study, some avoidable causes, such as UTIs, might be more amenable to intervention without an admission. Finally, visiting restrictions and enhanced infection control measures might have led to fewer admissions due to other communicable infections. However, our analysis does not allow us to differentiate whether admissions were prevented through out of hospital care, whether treatment in the care home was prioritised, or whether conditions remained undiagnosed. In addition, further research is needed to examine the outcomes for patients and residents during this period. The rapid and sustained changes in care pathways highlight the increased need care workers and families have for support from geriatricians and other health care staff in advance care planning with patients [44].

Elective admission rates for all conditions were lowest during April and rose through May and June but remained far below historical levels until the end of June. As non-urgent elective procedures were paused for all patients in March 2020, it is important to interpret these findings within the context of overall admission patterns. According to data published by the NHS, elective admissions across the healthcare system fell by 56% between March and May 2020, compared to the same period in the year before [45]. The findings of this study therefore suggest that care home residents were affected more strongly by the reduction in hospital admissions, with potentially concerning consequences for unmet elective care need. If unmet need is concentrated in high symptom burden conditions such as cataract then, while not prolonging life, lack of treatment will have a significant impact on quality of life [46].

Conclusion

This study is the first comprehensive national analysis of care home residents’ hospital use in England during the early months of the COVID-19 outbreak. Our study shows that there was a substantial decline in hospital admissions of care home residents during the early months of the pandemic, potentially resulting in substantial unmet healthcare need in residential care settings.

Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Data Management Team at the Health Foundation for their work to prepare the data extract and manage information governance. We also thank our colleagues Adam Steventon, Hannah Knight, Mai Stafford, Therese Lloyd, Rebecca Fisher and Stefano Conti for their input at various stages of the project and for helpful comments on previous versions of this article. This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support.

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV) coronavirus |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| ICD-10 | International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision |

| IMD | Index of Multiple Deprivation |

| OPCS4 | Office for Population Censuses and Surveys Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures, fourth revision |

| LRTI | lower respiratory tract infection |

| LSOA | Lower Layer Super Output Area |

| SD | standard deviation |

| UTI | urinary tract infection |

| w/c | week commencing |

Funding Statement

This study was funded by The Health Foundation as part of core staff member activity.

Contributors: SD conceived the study and SD and FG designed the study. FG, RB and KH analysed and interpreted the data. FG, KH and SD drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to, read, and approved the final manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. SD is the guarantor.

Supplementary Appendices: Appendix Table S1. ICD-10 chapters, diagnosis code ranges and chapter descriptions.

Appendix Table S2. ICD-10 diagnosis codes for potentially avoidable causes of emergency admissions.

Appendix Table S3. Comparison of baseline characteristics of the cohorts of residential care home and nursing home residents in January 2019 and January 2020.

Appendix Table S4. Number and percentage of COVID-19 hospital admissions with additional diagnosis codes for acute coronary syndromes or stroke (1 March to 31 May 2020), by care home type.

Appendix Table S5. Number of emergency admissions and changes in the number of emergency admissions between 1 March and 31 May in 2019 and 2020, by care home type and ICD-10 chapter of the primary diagnosis code.

Appendix Table S6. Number of emergency hospital admissions for acute coronary syndromes or stroke between 1 March and 31 May in 2019 and 2020, by care home type.

Appendix Table S7. Number and rates of potentially avoidable emergency admissions between 1 March and 31 May in 2019 and 2020, by primary admission reason and care home type.

Appendix Table S8. Number of admissions with cataract procedures between 1 March and 31 May in 2019 and 2020, by care home type.

Appendix Figure S1. Data cleaning workflow to create cohorts of care home residents in January 2019 and January 2020.

Appendix Figure S2. Assessment of similarity between cohorts of care home residents in January 2019 and January 2020.

Appendix Figure S3. Number and percentage of COVID-19 hospital admissions between 1 March and 31 May 2020, by number of additional diagnoses codes and care home type.

Appendix Figure S4. Number and percentage of COVID-19 hospital admissions with additional diagnosis codes in other ICD-10 chapters (1 March to 31 May 2020), by care home type.

Appendix Figure S5. Assessment of similarity of the characteristics between care home residents admitted to National Health Service hospital trusts in England for suspected or confirmed COVID-19 or for other primary diagnoses, by care home type (1 March to 31 May 2019, and 1 March to 31 May 2020).

Ethics approval

As we used routinely collected and pseudonymised data for our analysis, which were made available through an agreement approved by NHS England, no further ethics approval was required.

Availability of data and materials

The analysis code is available at https://github.com/HFAna−lyticsLab/COVID19_care_homes. Data used in this study cannot be made publicly available due to the conditions of the data sharing agreement.

References

- 1.Salcher-Konrad M, Jhass A, Naci H, et al. COVID-19 related mortality and spread of disease in long-term care: a living systematic review of emerging evidence (version at 29 June 2020). medRxiv Published Online First: 2020. 10.1101/2020.06.09.20125237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office for National Statistics. Deaths involving COVID-19 in the care sector, England and Wales: deaths occurring up to 12 June 2020 and registered up to 20 June 2020 (provisional). Released 3 July 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/deathsinvolvingcovid19inthecaresectorenglandandwales/deathsoccurringupto12june2020andregisteredupto20reakjune2020provisional (accessed 20 July 2020).

- 3.Morciano M, Stokes J, Kontopantelis E, et al. Excess mortality for care home residents during the first 23 weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic in England: a national cohort study. BMC Med 2021;19. 10.1186/s12916-021-01945-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Sabo RT, et al. Excess Deaths from COVID-19 and Other Causes, March-July 2020. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc 2020;324:510–3. 10.1001/jama.2020.19545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd T, Conti S, Santos F, et al. Effect on secondary care of providing enhanced support to residential and nursing home residents: A subgroup analysis of a retrospective matched cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf 2019;28:534–46. 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-009130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon AL, Franklin M, Bradshaw L, et al. Health status of UK care home residents: A cohort study. Age Ageing 2014;43:97–103. 10.1093/ageing/aft077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolters A, Santos F, Lloyd T, et al. Emergency admissions to hospital from care homes: how often and what for? Health Foundation. 2019. ISBN: 978-1-911615-27-9. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/upload/publications/2019/Emergency-admissions-from-care-homes-IAU-Q02.pdf

- 8.Shah SM, Carey IM, Harris T, et al. Mortality in older care home residents in england and wales. Age Ageing 2013;42:209–15. 10.1093/ageing/afs174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHS England and NHS Improvement. Letter to chief executives of all NHS trusts and foundation trusts, CCG accountable officers, GP practices and primary care networks, and providers of community health services. 17 March 2020. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/urgent-next-steps-on-nhs-response-to-covid-19-letter-simon-stevens.pdf (accessed 7 August 2020).

- 10.NHS England and Improvement. A&E Attendances and Emergency Admissions 2020-21. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/ae-waiting-times-and-activity/ae-attendances-and-emergency-admissions-2020-21/ (accessed 4 December 2020).

- 11.British Geriatrics Society. Managing the Covid-19 pandemic in care homes (version 3, updated 2 June 2020). https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/covid-19-managing-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-care-homes (accessed 7 August 2020).

- 12.NHS England and NHS Improvement. COVID-19 response: Primary care and community health support care home residents. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/COVID-19-response-primary-care-and-community-health-support-care-home-residents.pdf

- 13.Care Quality Commission. Access to hospital care and treatment for older and disabled people living in care homes and in the community during the pandemic. 2020. https://www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-providers/adult-social-care/access-hospital-care-treatment-older-disabled-people-living (accessed 17 August 2020).

- 14.Care Quality Commission. Review of Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interim report. 2020. https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/themed-work/review-do-not-attempt-cardiopulmonary-resuscitation-decisions-during-covid

- 15.Care Quality Commission. The state of health care and adult social care in England 2019/20. 2020. 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.12.760 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Queen’s Nursing Institute. The Experience of Care Home Staff During Covid-19. 2020. https://www.qni.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/The-Experience-of-Care-Home-Staff-During-Covid-19-2.pdf

- 17.Carter B, Collins JT, Barlow-Pay F, et al. Nosocomial COVID-19 infection: examining the risk of mortality. The COPE-Nosocomial Study (COVID in Older PEople). J Hosp Infect 2020;106:376–84. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Propper C, Stockton I, Stoye G. COVID-19 and disruptions to the health and social care of older people in England. Institute for Fiscal Studies. 2020. ISBN: 978-1-80103-014-4. https://ifs.org.uk/uploads/BN309-COVID-19-and-disruptions-to-the-health-and-social-care-of-older-people-in-England-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodgson K, Grimm F, Vestesson E, et al. Briefing: Adult social care and COVID-19. Assessing the impact on social care users and staff in England so far. Health Foundation. 2020. 10.37829/HF-2020-Q16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burton JK, Goodman C, Guthrie B, et al. Closing the UK care home data gap – methodological challenges and solutions. Int J Popul Data Sci 2020;5. 10.23889/ijpds.v5i4.1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soong J, Poots AJ, Scott S, et al. Developing and validating a risk prediction model for acute care based on frailty syndromes. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008457. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding Algorithms for Defining Comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 Administrative Data. Med Care 2005;43:1130–9. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:676–82. 10.1093/aje/kwq433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. COVID-19 coding in ICD-10. 2020. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases/emergency-use-icd-codes-for-covid-19-disease-outbreak (accessed 9 June 2021).

- 25.Mafham MM, Spata E, Goldacre R, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and admission rates for and management of acute coronary syndromes in England. Lancet 2020;396:381–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31356-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris S, Ramsay AIG, Boaden RJ, et al. Impact and sustainability of centralising acute stroke services in English metropolitan areas: Retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics and stroke national audit data. BMJ 2019;364:l1. 10.1136/bmj.l1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Floud S, Kuper H, Reeves GK, et al. Risk Factors for Cataracts Treated Surgically in Postmenopausal Women. Ophthalmology 2016;123:1704–10. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Care Quality Commission. The state of health care and adult social care in England in 2012/13. 2013. ISBN: 978-0-10298-727-0. https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/cqc_soc_report_2013_lores2.pdf

- 29.Care Quality Commission. The state of health care and adult social care in England. Technical Annex 1: Avoidable admissions. 2013. https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/state_of_care_annex1.pdf

- 30.Flury BK, Riedwyl H. Standard Distance in Univariate and Multivariate Analysis. Am Stat 1986;40:249–51. 10.1080/00031305.1986.10475403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2019. https://www.r-project.org

- 32.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Increase in fatal cases of COVID-19 among long-term care facility residents. 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Increase-fatal-cases-of-COVID-19-among-long-term-care-facility-residents.pdf

- 33.Scottish Government - Community Health and Social Care Directorate. Coronavirus (COVID-19): care home outbreaks - root cause analysis. 2020. ISBN: 978-1-80004-285-8. https://www.gov.scot/publications/root-cause-analysis-care-home-outbreaks/ (accessed 10 May 2021).

- 34.Comas-Herrera A, Zalakain J, Lemmon E, et al. Mortality associated with COVID-19 in care homes: international evidence. Last updated: 1st February, 2021. https://ltccovid.org/2020/04/12/mortality-associated-with-covid-19-outbreaks-in-care-homes-early-international-evidence/

- 35.Ward H, Atchison C, Whitaker M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence in England following the first peak of the pandemic. Nat Commun 2021;12. 10.1038/s41467-021-21237-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santos F, Conti S, Wolters A. A Novel Method for Identifying Care Home Residents in England: A Validation Study. Published Online First: 2021. 10.13140/RG.2.2.12720.69126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burton JK, Bayne G, Evans C, et al. Evolution and effects of COVID-19 outbreaks in care homes: a population analysis in 189 care homes in one geographical region of the UK. Lancet Heal Longev 2020;1:e21–31. 10.1016/s2666-7568(20)30012-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Audit Office. The adult social care market in England. 2021. ISBN: 978-1-78604-367-2. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/The-adult-social-care-market-in-England.pdf

- 39.Marshall M, Pfeifer N, de Silva D, et al. An evaluation of a safety improvement intervention in care homes in England: a participatory qualitative study. J R Soc Med 2018;111:414–21. 10.1177/0141076818803457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emmerson C, Adamson JP, Turner D, et al. Risk factors for outbreaks of COVID-19 in care homes following hospital discharge: A national cohort analysis. Influenza Other Respi Viruses 2021;15:371–80. 10.1111/irv.12831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Office for National Statistics. Impact of coronavirus in care homes in England: 26 May to 19 June 2020 (Released 3 July 2020). 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/impactofcoronavirusin−carehomesinenglandvivaldi/26mayto19june2020 (accessed 9 December 2020).

- 42.Mathie E, Goodman C, Crang C, et al. An uncertain future: The unchanging views of care home residents about living and dying. Palliat Med 2012;26:734–43. 10.1177/0269216311412233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Department of Health & Social Care, Public Health England, Care Quality Commission and NHS England. Admission and care of residents in a care home during COVID-19 (updated 31 July 2020). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-admission-and-care-of-people-in-care-homes/coronavirus-covid-19-admission-and-care-of-people-in-care-homes (accessed 7 August 2020).

- 44.Gordon AL, Goodman C, Achterberg W, et al. Commentary: COVID in care homes—challenges and dilemmas in healthcare delivery. Age Ageing 2020;49:701–5. 10.1093/ageing/afaa113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.NHS England. Monthly Hospital Activity Data. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/hospital-activity/monthly-hospital-activity/mar-data/ (accessed 21 May 2021).

- 46.Owsley C, McGwin G, Scilley K, et al. Impact of cataract surgery on health-related quality of life in nursing home residents. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91:1359–63. 10.1136/bjo.2007.118547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The analysis code is available at https://github.com/HFAna−lyticsLab/COVID19_care_homes. Data used in this study cannot be made publicly available due to the conditions of the data sharing agreement.