Abstract

Chronic diarrhea and constipation are common in adolescents and are associated with depression and anxiety. However, the association was not reported in adolescents adjusted for other psychological factors (resilience, personality traits, perceived stress, and suicidal ideation). Therefore, we investigated the significant psychological factors predicting chronic diarrhea and constipation in adjusted individuals for co-variables.

A total of 819 Korean high school students who completed bowel health and psychological questionnaires were enrolled in this study. Depression and anxiety were assessed using validated questionnaires. We used multivariate analyses, controlling for demographic, dietary, lifestyle, and psychological variables to predict chronic diarrhea and constipation.

Chronic diarrhea and constipation were more common in individuals with depression (22.3% and 18.6%, respectively) than in individuals with no depression (7.0% and 10.9%, respectively). In addition, they were more prevalent in individuals with anxiety (24.5% and 18.6%, respectively) than in individuals with no anxiety (9.1% and 12.7%, respectively). Multivariate analyses showed that resilience (adjusted risk ratio [aRR] = 0.98, adjusted 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.97–0.99), moderate (aRR = 6.77, adjusted 95% CI = 3.55–12.91), and severe depression (aRR = 7.42, adjusted 95% CI = 3.61–15.27) were associated with chronic diarrhea. Only mild depression was associated with chronic constipation (aRR = 2.14, adjusted 95% CI = 1.36–3.38). However, anxiety was not significantly associated with chronic diarrhea or constipation.

Among the psychological factors predicting disordered bowel habits, resilience and moderate and severe depression were significant predictors of chronic diarrhea, but not anxiety. Furthermore, only mild depression was an independent predictor of chronic constipation.

Keywords: bowel habits, chronic constipation, chronic diarrhea, psychology

1. Introduction

Functional bowel disorders are most commonly present with chronic diarrhea or constipation.[1] Chronic diarrhea is commonly defined as either functional diarrhea (loose or watery stools more than 25% of the defecation without predominant abdominal pain or bloating) or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with diarrhea (predominant abdominal pain and loose or watery stools).[2] Chronic constipation is also defined as either functional constipation (lumpy or hard stools more than 25% of the defecation without predominant abdominal pain or bloating) or IBS with constipation (predominant abdominal pain and lumpy or hard stools).[2] Chronic diarrhea and constipation are highly prevalent in the general population[1,3,4] and adolescents[5,6] and are commonly associated with reduced symptom-related quality of life, high medical healthcare utilization, and increased economic burden.[7]

Functional bowel disorders are developed not only in the gut but also in the gut-brain complex interactions among various factors, including gut dysbiosis or altered gut-brain signaling and regulation.[8] Based on this mechanism, two experimental studies suggested that anxiety and depression might result in the development of diarrhea and constipation because it is associated with increased and decreased bowel motility, respectively.[9,10] Although this hypothesis appears to be a plausible background, there are several conflicting data on the relationship between anxiety or depression and bowel habits. Two meta-analyses showed that anxiety and depression levels were higher in IBS patients than in healthy individuals, regardless of the IBS subtype.[11,12] In addition, two US studies found depression to be an independent factor for chronic diarrhea and constipation: individuals with more severe depression predicted a higher likelihood of diarrhea, and those with only mild depression predicted a higher likelihood of constipation.[3,13] However, these studies had no available data about rates or severity of anxiety, and the authors were unable to compare the outcomes for the bowel habits in individuals with depression and anxiety, which is also significantly associated with disordered bowel habits.[13]

In a systemic review, children with a history of adverse childhood experiences appear to be associated with a potential vulnerability to developing gastrointestinal comorbidities later in life.[14] Many individuals with adverse childhood experiences have been coping positively and have received less emotional distress because they are resilient.[14,15] Recently, one study found that lower resilience was associated with worse IBS symptom severity.[16] In addition, resilience might be influenced by neuroticism, psychological sensitivity to stress, and negative emotionality[17–19] and negatively associated with lifetime suicidal ideation.[20] However, there are no data on the relationship between resilience and disordered bowel habits after adjusting for various confounding factors such as demographic, lifestyle, dietary, and various psychological factors.

To date, there are no data to evaluate the prevalence of chronic diarrhea and constipation in individuals with depression and anxiety in Korean adolescents. Furthermore, no study has evaluated the psychological factors (depression, anxiety, resilience, personality traits, perceived stress, and suicidal ideation) associated with chronic diarrhea and constipation. Therefore, the current study is aimed to investigate the relationships between depression and bowel habits as well as anxiety and bowel habits in Korean high school students. It also investigated the significant psychological factors predicting chronic diarrhea and constipation, adjusting for co-variables.

2. Methods

2.1. Study subjects

A total of 985 high school students were recruited (16 to 18 years old) in Chungcheongnam-do, Korea. All participants provided written informed consent. Out of 985 participants, 166 were excluded for the following reasons: 141 failed to complete the bowel health and psychological questionnaires; 14 had chronic medical disease including 9 with asthma, 1 moyamoya disease, 1 congenital heart disease, 1 nephrotic syndrome, 1 epilepsy, and 1 ulcerative colitis; 7 took drugs for chronic diarrhea or constipation; and 4 took psychiatric medications. Therefore, 819 participants were finally included in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dankook University (IRB no. DKU 2021-01-017).

2.2. Bowel health questionnaires

The bowel health questionnaire in this study was used to identify subjects with chronic diarrhea or constipation. Participants were shown a card with colored pictures and descriptions of the 7 Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS type 1–type 7) and were asked, “Please look at this card and tell me the number that corresponds with your usual or most common stool type. ” Chronic constipation is defined as a usual or most common stool type of BSFS type 1 (separate hard lumps, like nuts) or type 2 (sausage-like but lumpy), and chronic diarrhea is defined as a usual or most common stool type of BSFS type 6 (fluffy pieces with ragged edges, a mushy stool) or type 7 (watery, no solid pieces).[3,4,13,21] The remaining subjects were classified as having normal bowel habits.

2.3. Anxiety and depression questionnaires

Anxiety and depression screeners were used to identify individuals with anxiety and depression. The anxiety screener consisted of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 Scale (GAD-7), which is a 7-item validated, publicly available anxiety questionnaire.[22] The GAD-7 assesses symptoms of anxiety, worry, fear, and irritability on a 4-point scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”) over the past two weeks, with scores ranging from 0 to 21.[22] The validated severity of anxiety cutoff scores were classified as follows: a total score of 0–4 was identified as no anxiety, 5–9 as mild anxiety, 10–14 as moderate anxiety, and 15–21 as severe anxiety.[22]

The depression screener consisted of the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Scale (PHQ-9), which is a 9-item validated and available depression questionnaire.[23] The PHQ-9 asks about symptoms of depression on a 4-point scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”) over the past two weeks, with scores ranging from 0 to 27.[23] The validated severity of depression cutoff scores were classified as follows: a total score of 0–4 indicates no depression; 5–9, mild depression; 10–14, moderate depression; and 15–27, severe depression.[23]

2.4. Other psychological questionnaires

2.4.1. Resilience questionnaires

To assess resilience, we applied as the ability the Conner-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)[24] and Brief Resilience Scale (BRS).[25] The CD-RISC contains validated and available 25-items on a 5-point scale from 0 (“not true at all”) to 4 (“true nearly all of the time”) over the past month with scores ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting greater resilience.[24]

In addition, to assess “the ability to bounce back”, the BRS is composed of 6-items, which were 1, 3, 5 as positive questions and 2, 4, 6 as negative questions, on a 5-point scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”) over the past month with scores ranging from 6 to 30; higher scores reflect “greater bounce back” resilience.[25]

2.4.2. Mini-international personality item pool (IPIP)[26]

The mini-IPIP was applied to evaluate personality traits, including extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and intellect/imagination. This is composed of 20 items, with scores ranging from 10 to 50.

2.4.3. Perceived stress score (PSS)[27]

We used PSS questionnaires to assess perceived stress over the past month with severity of chronic disease. This is composed of 10 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 40.

2.4.4. Scale for suicidal ideation (SSI)[28]

The SSI questionnaire was used to assess the presence of a suicidal ideation. This is composed of 19 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 38.

2.5. Co-variables

Information on age (16, 17, and 18 years), gender, and underlying chronic disease was self-reported. The body mass index was calculated using the subjects’ weight and height. The questionnaire on dietary habits was developed by including nine questions that were considered to affect chronic diarrhea and constipation.[29,30] Questions for dietary habits asked about regular diets and frequency of grains, fat, protein, liquid, fiber, dairy food, sweet food, and salty food intake.[29,30] For example, grains intake was divided into three categories: rarely consume (less than once a day), sometimes consume (once a day or more, but less than twice a day), and often consume (third time a day or more). The lifestyle questionnaire asked about vigorous physical activity per day. Vigorous physical activity was defined as vigorous-intensity activity that causes substantial increases in breathing or heart rate, such as hard exercise or lifting heavy loads for at least 10 min continuously.[21]

2.6. Statistical analysis

We first categorized subjects based on their bowel habits (BSFS types 1 and 2 for chronic constipation, BSFS types 3–5 for normal bowel habits, and BSFS types 6 and 7 for chronic diarrhea).[3,4,13] Differences between the subgroup's proportion of disordered bowel habits (i.e., chronic diarrhea and chronic constipation) were calculated and tested using t-tests, Chi-square analysis, and linear-by-linear association analysis. Logistic regression analyses were also performed to identify the factors associated with chronic diarrhea or constipation. Variables were included in log-binomial models, which provided mutually adjusted estimates of the risk ratios (RRs) of co-variables for chronic diarrhea or constipation. Both unadjusted and adjusted RRs were determined. All confidence intervals (CIs) were reported as 95%. P values of ≤.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant differences. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (version 24.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

A total of 819 participants completed the bowel health and psychological questionnaires. Among them, 124 (15.1%) and 123 (15.0%) had chronic diarrhea and constipation, respectively. In addition, there were 435 (53.1%) and 322 (39.3%) participants with depression and anxiety, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subjects characteristics.

| Variables | People with normal bowel habits | People with disordered bowel habits | P value |

| No. | 572 | 247 | |

| Age, years | .621 | ||

| 16 year | 87 (15.2) | 33 (13.4) | |

| 17 year | 277 (48.4) | 116 (47.0) | |

| 18 year | 208 (36.4) | 98 (39.7) | |

| Gender | .039 | ||

| Male | 319 (55.8) | 118 (47.8) | |

| Female | 253 (44.2) | 129 (52.2) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.2 ± 3.9 | 22.0 ± 3.3 | .666 |

| Physical activity | .006 | ||

| 6–7 day/week | 79 (13.8) | 21 (8.5) | |

| 2–5 day/week | 250 (43.7) | 99 (40.1) | |

| 0–1 day/week | 243 (42.5) | 127 (51.4) | |

| Regular mealtime | .093 | ||

| Regular | 167 (29.2) | 64 (25.9) | |

| Sometimes regular | 239 (41.8) | 95 (38.5) | |

| Irregular | 166 (29.0) | 88 (35.6) | |

| Grain intake | .051 | ||

| Often consume | 261 (45.6) | 98 (39.7) | |

| Sometimes consume | 256 (44.8) | 115 (46.6) | |

| Rarely consume | 55 (9.6) | 34 (13.8) | |

| Fat intake | .607 | ||

| Often consume | 155 (27.1) | 77 (31.2) | |

| Sometimes consume | 267 (46.7) | 103 (41.7) | |

| Rarely consume | 150 (26.2) | 67 (27.1) | |

| Protein intake | .016 | ||

| Often consume | 179 (31.3) | 67 (27.1) | |

| Sometimes consume | 214 (37.4) | 76 (30.8) | |

| Rarely consume | 179 (31.3) | 104 (42.1) | |

| Liquid intake | .954 | ||

| Often consume | 167 (29.2) | 77 (31.2) | |

| Sometimes consume | 314 (54.9) | 127 (51.4) | |

| Rarely consume | 91 (15.9) | 43 (17.4) | |

| Fiber intake | .153 | ||

| Often consume | 188 (32.9) | 73 (29.6) | |

| Sometimes consume | 234 (40.9) | 96 (38.9) | |

| Rarely consume | 150 (26.2) | 78 (31.6) | |

| Dairy food intake | .374 | ||

| Often consume | 240 (42.0) | 98 (39.7) | |

| Sometimes consume | 260 (45.5) | 112 (45.3) | |

| Rarely consume | 72 (12.6) | 37 (15.0) | |

| Sweet food intake | .346 | ||

| Often consume | 92 (16.1) | 46 (18.6) | |

| Sometimes consume | 233 (40.7) | 101 (40.9) | |

| Rarely consume | 247 (43.2) | 100 (40.5) | |

| Salty food intake | .027 | ||

| Often consume | 184 (32.2) | 64 (25.9) | |

| Sometimes consume | 268 (46.9) | 116 (47.0) | |

| Rarely consume | 120 (21.0) | 67 (27.1) | |

| Resilience (BRS) | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.7 | <.001 |

| Resilience (CD-RISC) | 61.4 ± 15.9 | 53.7 ± 17.7 | <.001 |

| Personality traits (Mini-IPIP) | |||

| Extraversion | 13.4 ± 3.4 | 12.5 ± 3.5 | .001 |

| Agreeableness | 14.4 ± 3.0 | 14.2 ± 3.0 | .521 |

| Conscientiousness | 12.6 ± 2.9 | 11.9 ± 3.0 | .001 |

| Neuroticism | 11.8 ± 3.0 | 12.8 ± 2.8 | <.001 |

| Intellect/Imagination | 14.3 ± 3.0 | 13.9 ± 3.0 | .079 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 5.25 ± 5.1 | 8.7 ± 6.0 | <.001 |

| 0–4 (Non-depressed) | 315 (55.1) | 69 (27.9) | |

| 5–27 (Depressed) | 257 (44.9) | 178 (72.1) | |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | 3.9 ± 5.0 | 6.5 ± 5.6 | <.001 |

| 0–4 (Non-anxious) | 389 (68.0) | 108 (43.7) | |

| 5–21 (Anxious) | 183 (32.0) | 139 (56.3) | |

| Perceived stress score | 15.9 ± 6.3 | 16.7 ± 6.3 | .092 |

| Scale for suicidal ideation | 4.7 ± 6.4 | 7.5 ± 8.1 | <.001 |

| Disordered bowel habits | |||

| Constipation (BSFS 1 or 2) | 123 (49.8) | ||

| Diarrhea (BSFS 6 or 7) | 124 (50.2) | ||

BRS = Brief Resilience Scale; BSFS = Bristol Stool Form Scale; CD-RISC = Conner-Davidson Resilience Scale; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 Scale; Mini-IPIP = Mini-International Personality Item Pool; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Scale.

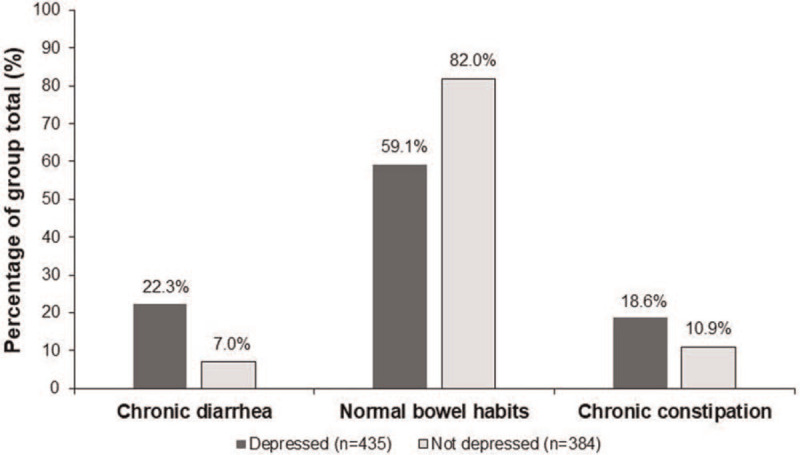

In this study, 40.9% (178/435) of individuals with depression and 17.9% (69/384) of individuals with no depression reported disordered bowel habits (P < .001). Chronic diarrhea was more common in individuals with depression (22.3%, 97/435) than in individuals with no depression (7.0%, 27/384) (P < .001). In addition, chronic constipation was more prevalent in individuals with depression (18.6%, 81/435) than in individuals with no depression (10.9%, 42/384) (P = .002) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Proportions of individuals with and with no depression with chronic diarrhea, normal bowel habits, and chronic constipation.

Similarly, 43.2% (139/322) of individuals with anxiety and 21.7% (108/497) of individuals with no anxiety reported disordered bowel habits (P < .001). Chronic diarrhea was more prevalent in individuals with anxiety (24.5%, 79/322) than in individuals with no anxiety (9.1%, 45/497) (P < .001). In addition, chronic constipation was more common in individuals with anxiety (18.6%, 60/322) than in individuals with no anxiety (12.7%, 63/497) (P = .021) (Figure S1, Supplemental Digital Content).

3.1. Predicting factors for chronic diarrhea

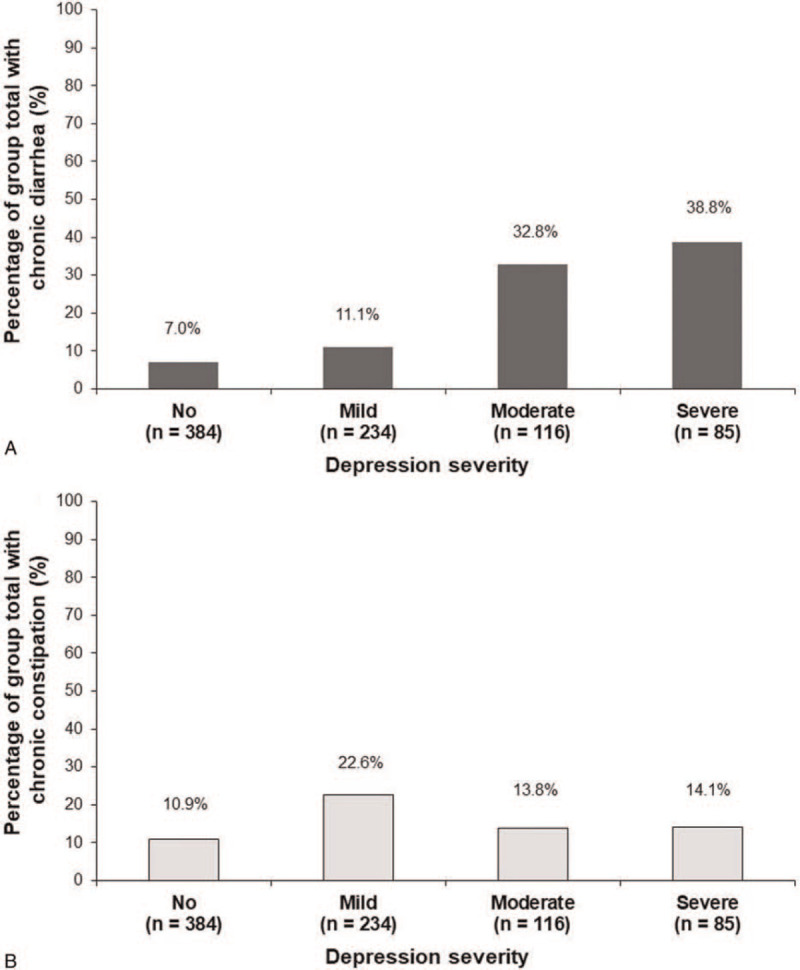

Figure 2A and Figure S2A, Supplemental Digital Content show the proportion of chronic diarrhea according to the severity of depression and anxiety, respectively. According to the severity of depression, the proportions of subjects with chronic diarrhea were 11.1%, 32.8%, and 38.8% in the mild, moderate, and severe depression groups, respectively (P < .001) (Fig. 2A). In addition, the proportions of subjects with chronic diarrhea were 17.4%, 34.8%, and 30.9% in the mild, moderate, and severe anxiety groups, respectively (P < .001) (Figure S2A, Supplemental Digital Content).

Figure 2.

Proportions of population with chronic diarrhea (A) and chronic constipation (B) according to the severity of depression.

Univariate analyses showed that resilience (BRS and CD-RISC), personality traits (extraversion, conscientiousness, and neuroticism), depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation were significantly associated with chronic diarrhea (Table 2). In multivariate analyses after adjusting for co-variables, resilience (CD-RISC; adjusted RR = 0.98, adjusted 95% CI = 0.97–0.99), moderate (adjusted RR = 6.77, adjusted 95% CI = 3.55–12.91), and severe depression (adjusted RR = 7.42, adjusted 95% CI = 3.61–15.27) independently predicted chronic diarrhea among the psychological factors (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses predicting chronic diarrhea.

| Univariate analyses | Multivariate analyses | ||||

| Variables | Unadjusted RR | Unadjusted 95% CI | Adjusted RR∗ | Adjusted 95% CI | Adjusted P value |

| Age, years | |||||

| 16 year | — | — | — | — | — |

| 17 year | 1.51 | 0.80–2.86 | 1.89 | 0.92–3.89 | .083 |

| 18 year | 1.61 | 0.84–3.08 | 1.93 | 0.92–4.02 | .081 |

| Female gender | 1.22 | 0.83–1.78 | 0.86 | 0.54–1.39 | .548 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1.01 | 0.96–1.06 | 1.01 | 0.96–1.07 | .686 |

| Vigorous physical activity | 0.52 | 0.26–1.06 | 0.66 | 0.30–1.46 | .306 |

| Regular mealtime | 1.58 | 0.99–2.50 | 1.40 | 0.82–2.39 | .213 |

| Frequent grain intake | 1.23 | 0.84–1.82 | 0.83 | 0.51–1.35 | .448 |

| Frequent fat intake | 0.80 | 0.53–1.21 | 0.75 | 0.46–1.22 | .246 |

| Frequent protein intake | 1.28 | 0.83–1.97 | 0.99 | 0.60–1.67 | .990 |

| Frequent liquid intake | 1.09 | 0.71–1.67 | 1.12 | 0.65–1.94 | .676 |

| Frequent fiber intake | 1.35 | 0.88–2.07 | 1.26 | 0.75–2.11 | .390 |

| Frequent dairy food intake | 1.13 | 0.77–1.68 | 1.08 | 0.65–1.79 | .772 |

| Frequent sweet food intake | 0.82 | 0.50–1.33 | 0.85 | 0.47–1.54 | .596 |

| Frequent salty food intake | 1.36 | 0.88–2.11 | 1.13 | 0.67–1.92 | .643 |

| Resilience (BRS) | 0.42 | 0.31–0.56 | 0.90 | 0.58–1.41 | .644 |

| Resilience (CD-RISC) | 0.96 | 0.95–0.97 | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | .003 |

| Personality traits (Mini-IPIP) | |||||

| Extraversion | 0.92 | 0.87–0.97 | 0.99 | 0.92–1.07 | .896 |

| Agreeableness | 0.95 | 0.89–1.01 | 1.01 | 0.93–1.10 | .756 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.87 | 0.82–0.93 | 0.96 | 0.88–1.04 | .273 |

| Neuroticism | 1.14 | 1.06–1.22 | 0.99 | 0.91–1.09 | .862 |

| Intellect/Imagination | 0.95 | 0.89–1.01 | 1.00 | 0.93–1.08 | .969 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | |||||

| No (0–4) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Mild (5–9) | 1.65 | 0.94–2.91 | 1.60 | 0.88–2.91 | .124 |

| Moderate (10–14) | 6.44 | 3.71–11.17 | 6.77 | 3.55–12.91 | <.001 |

| Severe (15–27) | 8.39 | 4.67–15.08 | 7.42 | 3.61–15.27 | <.001 |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | |||||

| No (0–4) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Mild (5–9) | 2.12 | 1.29–3.47 | 1.07 | 0.55–2.09 | .841 |

| Moderate (10–14) | 5.37 | 3.15–9.15 | 1.31 | 0.57–3.04 | .529 |

| Severe (15–21) | 4.49 | 2.35–8.60 | 0.71 | 0.25–2.02 | .522 |

| Perceived stress score | 1.03 | 0.99–1.06 | 0.96 | 0.93–1.00 | .060 |

| Scale for suicidal ideation | 1.07 | 1.04–1.09 | 0.99 | 0.95–1.02 | .405 |

BRS = Brief Resilience Scale; BSFS = Bristol Stool Form Scale; CD-RISC = Conner–Davidson Resilience Scale; CI = confidence interval; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 Scale; Mini-IPIP = Mini-International Personality Item Pool; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Scale; RR = risk ratio.

Multivariate analyses adjusting for the following variables: age, gender, body mass index, vigorous physical activity, regular mealtime, frequent grain intake, frequent fat intake, frequent protein intake, frequent liquid intake, frequent fiber intake, frequent dairy food intake, frequent sweet food intake, frequent salty food intake, resilience (BRS), resilience (CD-RISC), personality traits (mini-IPIP), depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7), perceived stress score, and scale for suicidal ideation.

3.2. Predicting factors for chronic constipation

Figure 2B and Figure S2B, Supplemental Digital Content show the proportion of chronic constipation according to the severity of depression and anxiety, respectively. According to the severity of depression, the proportions of subjects with chronic constipation were 22.6%, 13.8%, and 14.1% in the mild, moderate, and severe depression groups, respectively (P = .224) (Fig. 2B). In addition, the proportions of subjects with chronic constipation were 22.5%, 14.6%, and 12.7% in the mild, moderate, and severe anxiety groups, respectively (P = .368) (Figure S2B, Supplemental Digital Content).

Univariate analyses revealed that resilience (BRS), personality traits (neuroticism), mild depression, and mild anxiety were significantly associated with chronic constipation (Table 3). However, only mild depression (adjusted RR = 2.14, adjusted 95% CI = 1.36–3.38) was an independent predictor for chronic constipation in the multivariate analyses (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses predicting chronic constipation.

| Univariate analyses | Multivariate analyses | ||||

| Variables | Unadjusted RR | Unadjusted 95% CI | Adjusted RR∗ | Adjusted 95% CI | Adjusted P value |

| Age, years | |||||

| 16 year | — | — | — | — | — |

| 17 year | 0.81 | 0.47–1.42 | 0.76 | 0.42–1.37 | .355 |

| 18 year | 0.93 | 0.53–1.65 | 0.91 | 0.49–1.67 | .753 |

| Female gender | 1.39 | 0.95–2.05 | 1.27 | 0.81–1.97 | .294 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.98 | 0.93–1.03 | 0.99 | 0.94–1.06 | .943 |

| Vigorous physical activity | 0.75 | 0.40–1.41 | 0.97 | 0.49–1.92 | .932 |

| Regular mealtime | 0.86 | 0.57–1.30 | 0.74 | 0.46–1.18 | .204 |

| Frequent grain intake | 1.21 | 0.82–1.79 | 1.27 | 0.80–2.02 | .314 |

| Frequent fat intake | 0.91 | 0.60–1.38 | 0.90 | 0.57–1.44 | .670 |

| Frequent protein intake | 1.09 | 0.72–1.67 | 1.02 | 0.64–1.65 | .927 |

| Frequent liquid intake | 0.79 | 0.53–1.19 | 0.69 | 0.42–1.14 | .147 |

| Frequent fiber intake | 0.97 | 0.64–1.45 | 0.85 | 0.53–1.36 | .491 |

| Frequent dairy food intake | 1.03 | 0.70–1.52 | 1.07 | 0.66–1.74 | .781 |

| Frequent sweet food intake | 0.92 | 0.56–1.52 | 1.06 | 0.61–1.86 | .836 |

| Frequent salty food intake | 1.22 | 0.79–1.87 | 1.39 | 0.85–2.28 | .189 |

| Resilience (BRS) | 0.73 | 0.55–0.98 | 0.80 | 0.51–1.23 | .304 |

| Resilience (CD-RISC) | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | .846 |

| Personality traits (Mini-IPIP) | |||||

| Extraversion | 0.97 | 0.92–1.02 | 0.93 | 0.86–1.00 | .059 |

| Agreeableness | 1.03 | 0.97–1.10 | 1.08 | 0.99–1.17 | .099 |

| Conscientiousness | 1.00 | 0.94–1.07 | 1.05 | 0.97–1.13 | .225 |

| Neuroticism | 1.08 | 1.01–1.15 | 1.07 | 0.99–1.15 | .075 |

| Intellect/Imagination | 0.98 | 0.92–1.05 | 1.01 | 0.94–1.09 | .811 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | |||||

| No (0–4) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Mild (5–9) | 2.38 | 1.53–3.71 | 2.14 | 1.36–3.38 | .001 |

| Moderate (10–14) | 1.30 | 0.70–2.42 | 1.11 | 0.58–2.10 | .759 |

| Severe (15–27) | 1.34 | 0.67–2.67 | 0.96 | 0.45–2.05 | .908 |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | |||||

| No (0–4) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Mild (5–9) | 2.00 | 1.29–3.10 | 1.56 | 0.89–2.72 | .123 |

| Moderate (10–14) | 1.18 | 0.62–2.25 | 0.88 | 0.36–2.14 | .775 |

| Severe (15–21) | 1.01 | 0.44–2.32 | 0.58 | 0.17–1.92 | .371 |

| Perceived stress score | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | .535 |

| Scale for suicidal ideation | 1.02 | 0.99–1.04 | 1.00 | 0.97–1.04 | .888 |

BRS = Brief Resilience Scale; BSFS = Bristol Stool Form Scale; CD-RISC = Conner–Davidson Resilience Scale; CI = confidence interval; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 Scale; Mini-IPIP = Mini-International Personality Item Pool; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Scale; RR = risk ratio.

Multivariate analyses adjusting for the following variables: age, gender, body mass index, vigorous physical activity, regular mealtime, frequent grain intake, frequent fat intake, frequent protein intake, frequent liquid intake, frequent fiber intake, frequent dairy food intake, frequent sweet food intake, frequent salty food intake, resilience (BRS), resilience (CD-RISC), personality traits (mini-IPIP), depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7), perceived stress score, and scale for suicidal ideation.

4. Discussion and conclusions

This is the first study to investigate the relationships between various psychological factors (depression, anxiety, resilience, personality traits, perceived stress, and suicidal ideation) and bowel habits (diarrhea, constipation and normal) in Korean high school students. After adjusting for co-variables including demographic, dietary, lifestyle, and psychological factors, depression remained positively associated with chronic diarrhea and constipation. Furthermore, resilience was negatively associated with chronic diarrhea.

Our findings showed that the severity of depression and anxiety were significantly associated with chronic diarrhea, with more severe depression and anxiety predicting a higher likelihood of chronic diarrhea (P < .001 and < .001, respectively). However, both the severity of depression and anxiety were not significantly correlated with chronic constipation (P = .224 and = .368, respectively). Our findings are in contrast to previous experimental studies in which depression was associated with slower bowel transit; however, these studies had limitations, including small sample sizes and high potential for selection bias.[9,10] Therefore, our findings are consistent with the previous US representative population-based studies that severity of depression was associated with chronic diarrhea, but not constipation.[3,13]

No prior study has evaluated the relationships between other psychological factors (resilience, personality traits, perceived stress, and suicidal ideation) in addition to depression, anxiety, and bowel habits when balancing for co-variables. In our adjusted analyses, chronic diarrhea remained significantly associated with moderate depression (adjusted RR = 6.77, adjusted 95% CI = 3.55–12.91), severe depression (adjusted RR = 7.42, adjusted 95% CI = 3.61–15.27) and resilience (CD-RISC; adjusted RR = 0.98, adjusted 95% CI = 0.97–0.99). However, we also found that anxiety was not significantly associated with chronic diarrhea after adjusting for co-variables. These findings suggest that the higher prevalence of chronic diarrhea observed in individuals with depression in unadjusted analyses is attributable to depression itself, with other psychological factors of resilience in individuals with depression likely contributing as well. Furthermore, only mild depression (adjusted RR = 2.14, adjusted 95% CI = 1.36–3.38) was significantly correlated with chronic constipation in adjusted analyses as in the previous results.[3,13] The relationship between depression and disordered bowel habits is unique from other psychological characteristics because of the significant interplay between the gastrointestinal and central nervous system, also known as the gut-brain axis.[8] In other words, it is possible that activation of stress pathways may lead to dysfunction in the gut-brain axis, making individuals with depression more susceptible to chronic diarrhea or constipation.[31–34] Given the significant overlap between mood and disordered bowel habits, clinicians should be prepared to screen for concerns regarding depression and refer to appropriate health psychology services. Appropriate psychogastroenterological interventions (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy or gut-focused hypnotherapy) that are distinct from traditional psychotherapy might be helpful to individuals with depression with disordered bowel habits.[35,36]

Resilience is defined as a recovery and positive adaptation against emotional and environmental stressors and plays a role in individuals with vulnerability.[16,24,25,37] Our study used validated CD-RISC[24] and BRS[25] to evaluate resilience, and they were significantly associated with disordered bowel habits, as in a previous study.[16] However, only CD-RISC was negatively associated with chronic diarrhea in the adjusted analyses, but not with chronic constipation. These findings suggest that resilience might be a treatment target in individuals with depression with chronic diarrhea, apart from therapeutic interventions for depression itself. Therefore, resilience training programs that reduce mindfulness-based stress might be an effective treatment option for improving resilience.[38,39]

There were several limitations to the current study. First, the current study was cross-sectional in nature, and neither causation nor temporal relationships between variables could be determined. Second, there is an inherent risk of recall bias because it is based on self-reported data. Third, bowel habits were only assessed using the most common stool form without evaluating the endoscopic examinations, and they were not evaluated using other gastrointestinal symptoms including abdominal pain and other measurements of stool frequency. In addition, “chronicity” based on the wording of “usual or most common” BSFS stool form was approximated. Thus, it was not possible to discriminate individuals who met the Rome criteria for IBS from functional diarrhea or constipation and directly compare to those of studies that used other gastrointestinal symptoms and measurements of stool frequency. Finally, self-reported dietary intake (e.g., grain, fat food, dairy food, etc) was not sufficient to determine the exact daily consumption, and we could not quantitatively analyze dietary factors.

In conclusion, the current study investigated the relationships between various psychological factors (depression, anxiety, resilience, personality traits, perceived stress, and suicidal ideation) and bowel habits in adolescents. We found that chronic diarrhea and constipation were more common in individuals with depression than in individuals with no depression. Among the psychological factors predicting disordered bowel habits, moderate and severe depression and resilience were independent predictors for chronic diarrhea, but not anxiety. Furthermore, only mild depression was an independent predictor of chronic constipation. In the future, a large cohort study will be needed to identify the causation and temporal relationships between psychological factors and bowel habits.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Ji Young Kim, Myung Ho Lim.

Data curation: Ji Young Kim.

Formal analysis: Ji Young Kim.

Funding acquisition: Myung Ho Lim.

Investigation: Ji Young Kim.

Methodology: Ji Young Kim, Myung Ho Lim.

Project administration: Myung Ho Lim.

Supervision: Myung Ho Lim.

Validation: Ji Young Kim.

Visualization: Ji Young Kim.

Writing – original draft: Ji Young Kim.

Writing – review & editing: Myung Ho Lim.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BRS = Brief Resilience Scale, BSFS = Bristol Stool Form Scale, CD-RISC = Conner-Davidson Resilience Scale, CI = confidence interval, GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 Scale, IBS = irritable bowel syndrome, IPIP = International Personality Item Pool, PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Scale, PSS = Perceived Stress Score, RR = risk ratio, SSI = Scale for Suicide Ideation.

How to cite this article: Kim JY, Lim MH. Psychological factors to predict chronic diarrhea and constipation in Korean high school students. Medicine. 2021;100:27(e26442).

This study was conducted using the research fund of Dankook University in 2020.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

References

- [1].Palsson OS, Whitehead W, Törnblom H, Sperber AD. Prevalence of Rome IV functional bowel disorders among adults in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Gastroenterology 2020;158:1262–73e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Singh P, Mitsuhashi S, Ballou S, et al. Demographic and dietary associations of chronic diarrhea in a representative sample of adults in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sommers T, Mitsuhashi S, Singh P, et al. Prevalence of chronic constipation and chronic diarrhea in diabetic individuals in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Scarpato E, Kolacek S, Jojkic-Pavkov D, et al. Prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in children and adolescents in the Mediterranean region of Europe. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:870–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yamamoto R, Kaneita Y, Osaki Y, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome among Japanese adolescents: a nationally representative survey. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;30:1354–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology 2012;143:1179–87.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gorard DA, Gomborone JE, Libby GW, Farthing MJ. Intestinal transit in anxiety and depression. Gut 1996;39:551–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bennett EJ, Evans P, Scott AM, et al. Psychological and sex features of delayed gut transit in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut 2000;46:83–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fond G, Loundou A, Hamdani N, et al. Anxiety and depression comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014;264:651–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lee C, Doo E, Choi JM, et al. The increased level of depression and anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome patients compared with healthy controls: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;23:349–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ballou S, Katon J, Singh P, et al. Chronic diarrhea and constipation are more common in depressed individuals. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:2696–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chitkara DK, van Tilburg MA, Blois-Martin N, Whitehead WE. Early life risk factors that contribute to irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:765–74. quiz 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Anda RF, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Giles WH. Adverse childhood experiences and prescription drug use in a cohort study of adult HMO patients. BMC Public Health 2008;8:198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Park SH, Naliboff BD, Shih W, et al. Resilience is decreased in irritable bowel syndrome and associated with symptoms and cortisol response. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Campbell-Sills L, Cohan SL, Stein MB. Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behav Res Ther 2006;44:585–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gupta A, Love A, Kilpatrick LA, et al. Morphological brain measures of cortico-limbic inhibition related to resilience. J Neurosci Res 2017;95:1760–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mincic AM. Neuroanatomical correlates of negative emotionality-related traits: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia 2015;77:97–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brailovskaia J, Forkmann T, Glaesmer H, et al. Positive mental health moderates the association between suicide ideation and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord 2019;245:246–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Markland AD, Palsson O, Goode PS, et al. Association of low dietary intake of fiber and liquids with constipation: evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:796–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety 2003;18:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med 2008;15:194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Donnellan MB, Oswald FL, Baird BM, Lucas RE. The mini-IPIP scales: tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychol Assess 2006;18:192–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the scale for suicide ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979;47:343–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Song SW, Park SJ, Kim SH, Kang SG. Relationship between irritable bowel syndrome, worry and stress in adolescent girls. J Korean Med Sci 2012;27:1398–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Son YJ, Jun EY, Park JH. Prevalence and risk factors of irritable bowel syndrome in Korean adolescent girls: a school-based study. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mayer EA, Naliboff BD, Chang L, Coutinho SV. V. Stress and irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2001;280:G519–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tache Y, Martinez V, Million M, Wang L. Stress and the gastrointestinal tract III. Stress-related alterations of gut motor function: role of brain corticotropin-releasing factor receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2001;280:G173–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Monnikes H, Tebbe JJ, Hildebrandt M, et al. Role of stress in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Evidence for stress-induced alterations in gastrointestinal motility and sensitivity. Dig Dis 2001;19:201–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tache Y, Kiank C, Stengel A. A role for corticotropin-releasing factor in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2009;11:270–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Krasner SS, Katz LA, Gudleski GD, Blanchard EB. How does cognitive behavior therapy for irritable bowel syndrome work? A mediational analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterology 2007;133:433–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1350–65. quiz 66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:598–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Steinhardt M, Dolbier C. Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. J Am Coll Health 2008;56:445–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Joyce S, Shand F, Tighe J, Laurent SJ, Bryant RA, Harvey SB. Road to resilience: a systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. BMJ Open 2018;8:e017858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.