Abstract

The range of general and specific adverse event in total elbow arthroplasty is similar in principle and practice to all other revision prosthetic arthroplasty but with three particular challenges: loss of humeral and ulnar bone stock; insufficiency of the extensor ‘mechanism’; and the management of the ulnar nerve. Total elbow replacement is presently performed for the management of complex non-reconstructable distal humeral fractures in osteoporotic bone, for post-traumatic arthropathy, and for medically managed inflammatory arthritides in which metaphyseal bone architecture is often preserved while the articular surface is degenerate. In all these conditions the patient often presents for revision total elbow arthroplasty with relevant co-morbidities and relevant musculoskeletal dysfunction (for example: ipsilateral shoulder, wrist, thumb or hand dysfunction).

Infection is a universal concern for revision arthroplasty but where the soft tissue ‘envelope’ is compromised and already limited, as in the proximal forearm, it is difficult to eradicate, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

Bone loss compromises subsequent implantation of a revision prosthesis, while failure to restore the working lengths of the humerus and ulna reduces the strength of the flexor and extensor compartment muscles for elbow motion.

Failure to restore the continuity of the triceps aponeurosis - antebrachial fascia and triceps medial head-olecranon components of the extensor ‘mechanism’ also compromises extensor power. Prior triceps-dividing surgical approaches will determine the elasticity, and therefore pliability, of the extensor ‘mechanism’: this will have a role in determining how much gain in length of the humeral side can be safely achieved.

The ulnar nerve, and its management during elbow arthroplasty, is a source of frequent concern, particularly for revision of an elbow arthroplasty undertaken for distal non-reconstructable humeral articular fractures or post-traumatic arthropathy, in which the position of the ulnar nerve is never anatomic. For these reasons revision total elbow replacement (RTER) is challenging: it requires experience with surgical exposures of the elbow including the major nerve trunks, familiarity with the restoration of bone stock, a range of prostheses and techniques for prosthetic implantation, the ability to achieve adequate soft tissue cover and primary closure, and a logical approach to individualised rehabilitation.

Keywords: Revision, Elbow, Replacement, Infection, Bone loss, Triceps

1. Introduction

Adverse events (AE) following RTER are frequent,1 challenging to manage, and commonly result in functional decrements. The volume of RTER performed annually is low compared with all other revision arthroplasties, but as a higher proportion of all total elbow replacement (TER). The principles of surgical management of a patient requiring RTER are the same as those for any other revision arthroplasty: preserve and restore bone; preserve and restore soft tissues; protect nerves and limb perfusion; and consider the future.

The failed TER often presents after a long period of increasingly painful dysfunction, eventually culminating in an irreversible event, most commonly aseptic prosthetic loosening,2 or periprosthetic fracture. Presentation in clinical practice follows a period of decline in function or pain or both to the point where the functional decrement is sufficient that there is a loss of patient activation and independence or self-determination. The aim of the surgeon is to assess the magnitude and rate of functional decrement and match this knowledge with the functional needs as defined by the patient to devise an appropriate treatment for the failed TER. This review aims to describe a practical approach to the clinical assessment, surgical tactics employed in, and rehabilitation of a patient undergoing RTER.

2. Clinical assessment

When faced with a patient with elbow pain post-TER, it is important not only to focus on the elbow replacement but also the regional and systemic problems that could contribute to the symptoms. Table 1 outlines a comprehensive but not exhaustive overview of potential causes of pain in a patient with a failing TER.

Table 1.

Causes of pain in a failing TER: the articulation/implants may only be a part of a wider problem.

| systemic problem | regional problem | local/associated problem | infection | arthroplasty diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve | Nerve | Elbow joint | Systemic | What sort of elbow are we dealing with? |

| diabetes mellitus | spinal nerve/root | ulno-trochlear replacement implant failure/loosening | immunosuppression | ? Contracture/stiffness and contracture of juxta articular shunt muscle and ulnar nerve neuropathy |

| neuro-degenerative | peripheral nerve | radio-capitellar joint -replaced/not replaced. | ? Infection with tricep and collateral insufficiency in an unlinked replacement | |

| neuro-inflammatory | dysautonomia | proximal radio-ulnar joint | ? Systemic diabetic cheiralgia paresthetica with ulnar nerve entrapment | |

| CRPS | impingement of prosthesis | ? Unstable elbow with mechanical problem: bushing wear/collateral ligament insufficiency and loosening | ||

| instability | ||||

| impingement/longitudinal insufficiency | ||||

| Muscle | Muscle | Extra-articular | Extra-fascial | |

| polymyalgia | compartment syndrome | Tricep insufficiency | contamination | |

| immune disease | focal ischaemia | Juxtaartciular shunt muscle insufficiency (anconeus, common flexor/extensor tendon, tricep/, brachialis, brachioradialis) insufficiency | inoculation | |

| myopathy | Stiffness/Heterotopic ossification | haematogenous | ||

| statins | Enthesopathies | |||

| thyroid disorder | ||||

| osteomalacia | ||||

| genetic | ||||

| Bone | Bone | Articular | Intra-fascial | |

| osteoporosis | focal osteoporosis | Synovitis | contamination | |

| osteomalacia | focal osteonecrosis | Inflammatory | inoculation | |

| osteonecrosis | Idiopathic (contracted) | haematogenous | ||

| Collagen disorder | Articular | Articular | ||

| Vasculitis | Poly-debris or metal synovitis | contamination | ||

| inflammatory | inoculation | |||

| idiopathic (contracted) | haematogenous | |||

| Synovitis | Nerve | |||

| inflammatory arthritis | Ulnar nerve neuropathy | |||

| Radial nerve neuropathy |

The assessment of a painful TER and the work-up for revision surgery should follow a systematic outside-in approach (Table 2).

Table 2.

The clinical assessment of a failing TER includes an evaluation of the actual and potential (after explantation) concerns about the integument, subfascial soft tissues, the implants, and bone stock.

| Observation | Clinical exam | Simple Tests | Special tests | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin and superficial fascial compartment | Infection | Look/feel | Microbiological assessment: | |

| Tethering (risk to skin flap perfusion) | Serology: CRP, ESR, WCC and differential | |||

| Dehiscence (risk to skin flap healing) | Biopsy, aspiration | |||

| Atrophy of skin (need for additional skin restoration tactic) | IgE | |||

| Existing skin blood supply/healing potential (dysautonomic signs) | ||||

| Olecranon pressure ridge/olecranon bursitis (previous olecranon bursal infection) | ||||

| Cutaneous protective sensation, 2-point discrimination (especially over olecranon) | Feel | Sensory mapping | ||

| Subfascial compartment (anterior) | Continuity of biceps tendon | Look/feel/move | USS | MARS MRI |

| Major nerve trunks | Ulnar, MCNA, MCNF, Median, LCNF, Radial, PIN, SRN, PCNF | Look/feel/move | Sensorimotor mapping | EMG, NCS, USS (with Doppler mode), |

| MR angiogram | ||||

| Specific Ulnar nerve | Prior ulnar nerve surgery: anatomical location | Look/feel/move (instability of nerve trunk) | EMG, NCS, USS (with Doppler mode) | |

| Muscular compartments | Bulk, tone and activity | Look/move | USS | MARS MRI |

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| Specific Triceps ‘mechanism’ | What was the primary triceps mechanism management | Look/feel/move | USS | MARS MRI |

| Implants | Malalignment/instability | Look/feel/move – squeaking of implant | XR Orthogonal views | EUA ± arthrogram |

| Loosening | Feel/move | CT ± arthrogram ± biopsy | ||

| Bone: | bone loss (potential/actual) loosening | Feel/move | XR Orthogonal views | CT ± arthrogram ± biopsy |

|

|

3-D CT (custom planning) | ||

|

|

|||

|

Fracture: classification; relevance to future implantation strategy | Look/feel | ||

| Heterotopic ossification | Feel/move | |||

3. Integument, including (protective) sensory innervation

The skin around the previous incision and planned incision should be carefully examined to assess the vascularity of the skin, the skin tension over the olecranon ridge, the healing potential of the skin edges (particularly if multiple incisions have been used previously) and any diminution of cutaneous protective sensation.

4. Nerves

The major nerve trunks and their cutaneous branches should be examined for any evidence of iatropathic injury (with corresponding cutaneous dysaesthesia and neuroma, or distal motor deficit), extrinsic compression or traction neuropathy (even after anterior transposition), and intrinsic vasculopathic neuropathy (if the nerve has been previously mobilised intra-epineurally). The ulnar nerve should specifically be checked for the method of prior anterior transposition, signs of degeneration and regeneration (Tinel's sign), and any instability (recurrent motion-related subluxation).

5. Musculature

The juxta-articular muscles arranged collaterally around the elbow are stabilisers of the elbow (albeit less important in linked TER) while also performing an important load-sharing function. The shunt muscles of the anterior and posterior compartments (brachialis inserted on coronoid process, and triceps medial head inserted on olecranon) should also be examined with especial note taken of the management of the triceps anatomy during the primary TER. Infection, and staged surgical debridements or washouts may devitalise the local soft tissue and bony attachments of the extensor mechanism.3

6. Bone-implant

Malalignment of the elbow replacement is difficult to assess, but important to verify. Plain orthogonal radiographs are the basic investigation of choice. The triceps-on approach had been suggested to be causally related to malrotation of the ulnar component due to difficult access to the ulnar medullary cavity. Ulnar component malrotation may be a cause of torsional loosening of the humeral component in linked prostheses. In patients with long standing cubitus varus or angular deformity following previous trauma or trauma surgery, the asymmetric contracture of the medial soft tissues, and particularly the medial aspect of the triceps, will tend to angle the elbow arthroplasty in the same direction (and therefore lead to malrotation of one or both components) unless there is adequate soft tissue release or even rerouting of the medial triceps to centralise the pull over the ulna.4

Rheumatoid patients often have reduced bone density5 and the peri-articular bone quality in the failing TER is compounded by stress shielding or osteolysis and aseptic loosening. Auto- or allograft bone graft, allograft-prothesis composites6 or megaprostheses7,8 may be required in the presence of massive bone loss. If the dominant primary stability of the revision implant will be gained in a region distal to the isthmus, and fixation in the medullary cavity (which tends to expand towards the metaphyseal region) is required, then the revision implant may need to be longer than the standard recommendation of at least two cortical diameter widths.

7. Infection

Infection remains the greatest challenge of any revision arthroplasty. Basic serological tests (CRP, ESR, and WCC differential counts) are standard while more sophisticated microbiological tests become relevant as the complexity of the infection and its relationship to both the implants and the bones increases: the advice of clinical musculoskeletal microbiologists in the context of a multidisciplinary environment is valuable.

Revision TER is therefore a multifactorial problem. The combination of clinical examination and radiological investigation provides information about the state of the soft tissues, bone, and implants. Using an aide-memoire helps to avoid omissions of assessment. The interplay between these variables can be conceptualised and depicted in a 3-dimensional model (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The relationship between (1) the actual or predicted bone quality and extent after explantation, (2) the implant and implantation quality, and (3) the actual or predicted quality of the soft tissues after explantation is depicted. Each factor exists along a spectrum of quality ranging from ‘good’ (in which few or no special reconstructive surgical tactics are needed) to ‘poor’ (in which the most innovative and challenging surgical tactics might be required for an optimal outcome). A patient might exhibit different quality achievements for each factor, and so may be defined as a point in the x,y,z coordinate system at a distance from the ideal ‘normal’ (0,0,0). The surgical tactic for each factor is then guided by the requirement to end up as close to the ideal ‘normal’ as possible. In the figure, the patient from the case illustration is represented by a point, whose coordinates are x,y,z. This implies that there are x amounts of soft tissue problems actual/predicted; there is y amount of implant-related problems actual/predicted; and there are z amount of bone loss actual/predicted. To return this patient from the present condition (x,y,z) to normal (0,0,0) the surgeon has to define the surgical tactics needed to assess and reconstruct soft tissues (x), predict and overcome explantation and implantation difficulties (y), and assess and restore bone loss (z), and understand how each of these factors impact on the others. This in turn defines the surgical skill-set required, the inventory of implants and options needed, the employment of unusual surgical techniques or technologies, and the probable level of outcome that can be achieved. Such an analysis can help to guide where, how, and by whom R-TER might be undertaken.

8. Working diagnosis and further investigation

Clinical examination, basic imaging (orthogonal radiographs) and initial serological tests provide the basis for a preliminary working diagnosis. The presentation can be broadly categorised into three: the TER may be stiff (reduced active range of motion), weak (reduced active power of motion) or unstable (prosthetic loosening or dissociation, or both). A combination of any or all of these conditions may be present, with or without infection. A simple algorithm outlining the further investigation of these specific conditions is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The investigation of the three basic presentations or conditions of the failing TER.

| Following an assessment by history, examination, and orthogonal X-rays | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pain & dysfunction (definitely) from the arthroplasty | source of pain remains uncertain | |||

| Diagnostic local anaesthetic injection (US guidance): interrogate triceps tendon structure/ulnar nerve/intrinsic prosthetic instability (±stress radiograph ± EUA ± nerve conduction study/electromyography) | ||||

| from joint cavity |

not from joint cavity |

from both |

||

| The condition at presentation is predominantly: | ||||

| stiff |

weak |

unstable |

||

| If infection is suspected | If no infection suspected or additional cause for stiffness sought | Triceps mechanism insufficiency/neuropathy | Bone loss (humerus) – disturbance of length-tension relationship in triceps/biceps mechanisms | bone deficiency; ligament insufficiency; bushing wear/failure of linking mechanism |

| EUA | EUA | USS + LA (+steroid to cubital tunnel) +/− MARS MRI (peri-articular soft tissue) | CT | EUA + stress XR |

| Aspiration/arthroscopy + biopsy | CT | CT (±3D-CT ± arthroCT) + US ± MARS MRI (for peri-articular soft tissue) | ||

| PET CT/SPECT | ||||

NOTE: ulnar neuropathy may promote stiffness.

If it can be certain that the pain and dysfunction originate from the implant and/or implant-bone interface, then the further investigation is determined by one or more of the three working diagnoses. Examination under anaesthesia with fluoroscopy and joint aspiration aid the diagnosis of the cause(s) of stiffness due to infection, implant impingement9,10 implant malrotation or heterotopic ossification. Nerve conduction studies and ultrasonography (US, with Doppler augmentation) of the ulnar nerve distinguish the cause(s) of intrinsic neuropathy and extrinsic nerve compression. Imaging of the triceps mechanism and assessment of loss of bone length or subduction of a loose implant aids the assessment of the weak failing TER. A painful TER which presents with instability from a failing linking mechanism, or insufficient collateral ligaments in an unlinked implant, can be assessed with stress radiographs.11 Computerised tomography (CT) is essential to assess bone loss and implant alignment (and prepare for a bespoke implant solution if required). In all scenarios, infection needs to be considered and investigated.

A periprosthetic elbow joint infection is suspected in patients if there are signs of fever, persistent or increasing local pain, local swelling, erythema, wound dehiscence/blister with sinus or fistula formation, or radiolucent lines on radiographs depicting the bone-cement-implant interface. Several attempts to identify the infecting microorganism may be necessary to guide antimicrobial treatment and management of the implants. Investigation by US with guided aspiration and CT may help locate the infection to the extracapsular compartment (skin and subcutaneous tissues, including triceps), intracapsular compartment, or to the intraosseous compartment (osteomyelitis).

9. Summary

The clinical examination coupled with the information gathered from further investigations outlined above generates a complete working diagnosis leading to a logical and complete treatment plan. This can be thought of as a series of decision points, leading to a surgical tactic for each point:

-

1.

Soft tissue (skin and musculotendinous envelope): sufficient/not sufficient

-

2.

Bone after explantation: sufficient/not sufficient

-

3.

Implant: secure/not secure in bone

-

4.

Neurovascular condition: compromised/not compromised

-

5.

Infection: present/not present

10. Surgical management strategies

Treatment strategies are derived from the decision points described above adopting the ‘outside-in’ sequence.

11. Tourniquet, patient position

We prefer not to use a tourniquet since extensile exposure of the posterior compartment including exposure of the radial nerve is often required and the procedure duration is highly likely to exceed the safe duration of compression of the limb. The lateral decubitus position is optimal: this permits free mobility of the entire upper extremity, and access to the ipsilateral latissimus dorsi and posterior iliac crest for soft tissue and bone harvesting if indicated.

12. Skin

Attention is paid to retention of skin and cutaneous sensibility and planning the replacement of skin cover with local rotational skin flaps, local muscle flaps with skin grafting (using anconeus12 or brachioradialis13), or with pedicled or free myocutaneous flaps (eg. the latissimus dorsi).

13. Triceps

The overall functional outcome of the RTER will be determined by preservation and restoration of the continuity of the triceps mechanism with the olecranon and antebrachial fascia, and restoration of the length-tension relationship with the overall length of the arm. The triceps muscle and its distal attachments are elevated in continuity with the antebrachial fascia and mobilised sufficiently to permit reflection of the medial and lateral heads to the lateral side in continuity with the anconeus. The long head of triceps is mobilised to the medial side and can function to protect the ulnar nerve during further humeral dissection. This technique provides an interneural and intervascular approach to the dorsal aspect of the humerus and can be extended in an extensile fashion proximally as far as the axillary nerve, and distally to the wrist as the Boyd-Thompson approach. When the triceps is significantly attenuated, local augmentation or reconstruction using an anconeus flap or Achilles’ tendon allograft can be considered.14 Advancement V–Y plasty is not advocated since this devascularises the distal muscle and tendon and may be associated with failure to heal.

14. Ulnar nerve

We advocate dissecting the medial border of the triceps muscle and medial intermuscular septum proximally outside the region of surgical scarring to identify the ulnar nerve passing through the septum. The medial intermuscular septum should be released to improve the mobility of the nerve. The nerve is elevated with the more deeply placed vena nervora pedicles intact as far as possible, in order to optimise nerve perfusion. There is no consensus on what comprises best management of the ulnar nerve.7 Anterior transposition with external neurolysis may be necessary to mobilise the nerve to permit release of contractures for better alignment of the implants, particularly if the patient was symptomatic of the nerve pre-operatively.

15. Explantation and bone loss

The type of prosthesis implanted during the previous surgery and the security of implantation should be clear prior to revision. The bone stock remaining after extraction of the implant and removal of cement if present will determine if a standard prosthesis can be re-implanted. Periarticular bone loss with poor or insufficient ligament tissues may also preclude the use of an unlinked implant in the revision.15 Uncoupling of a constrained elbow arthroplasty helps to improve the access to both medullary canals. An elective osteotomy with cement extraction instruments (including flexible reamers with fluoroscopic control) can contribute to bone preservation.16 Ultrasonic cement removal tools are known to cause thermal injury to nerves and should be used with caution or avoided if possible.17 Cement removal can itself lead to cortical perforation and possible cement extravasation on final cementing: flexible endoscopy or a fine light source can be used to assess the integrity of the cortical wall as well as view any remaining cement.

While one of the aims of revision is to preserve bone stock, augmentation and reconstruction of weakened or deficient bone using morsellised or bulk allograft, or allograft-prosthesis composite constructs may be required. A mega-prosthesis may be required in the presence of non-reconstructible bone loss. To preserve bone stock, cement-in-cement reconstruction can be a viable option in cases of well cemented implant with no infection.18

16. Infection

A well-cemented and secure implant can be left in situ in the presence of infection after debridement (the DAIR principle19, 20, 21), when the infection is caused by a monocultured organism sensitive to simple antibiotic suppression in a healthy patient. The polymeric bushings should be revised. Radical debridement should be carried out to remove any devitalised tissue, cement debris and the fibro-granulomatous endosteal sheath. A two (or more)-stage revision strategy is an effective way of eradicating infection, but may not be optimal in an individual case given the increased risk of nosocomial infection, repeated bone debridement leading to further bone loss, and repeated scarring of the triceps, all of which may promote decrements in elbow function. Sufficient numbers of soft tissue and bone samples should be taken for microbiology in the case of suspected infection: five samples are recommended.

17. Case illustration

The following case illustrates many of the principle involved in RTER.

A 53-year-old scientist with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis on immunotherapy presented with painful unreliable, weak upper extremities. The analysis of the presentation follows the methodical approach outlined in Table 2.

18. Skin condition

There were multiple dorsal scars of the previous total elbow replacements. There was no skin tethering on the potential incision site or external signs of infection. The posterolateral and posteromedial synovia were mildly thickened on palpation.

19. Nerve & muscle condition and relevant function

Ulnar nerve function was grossly intact. The elbow extension and flexion were graded as MRC 3 (gravity ‘eliminated’) and MRC 4 respectively. Supination was blocked at 50% (MRC grade 4 power) and no pronation was available. Glenohumeral joint movements were limited to forward flexion to chest level (60 degrees) with no abduction. The shoulder external rotation was limited to minus 30°.

20. Bone and implant condition

Orthogonal radiographs showedvarus remodelling of the proximal humerus with likely rotator cuff insufficiency and glenoid medialisation (Fig. 2). There was medullary expansion proximally and cortical thinning distal to the prosthetic tip with cortical remodelling in the humerus. In addition, there were medial and lateral condylar fractures (Fig. 2) and posterior distal cortex breaching (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Overall, the humerus showed long term sclerotic changes indicating chronicity of bone remodelling but with imminent periprosthetic bone failure being highly likely.

Fig. 2.

Postero-anterior plain radiograph of the upper limb, showing the shoulder deformities as described, distal humeral condylar fractures, and the humeral implant loosening. The radial head has been excised and the radius has migrated proximally (after distal radio-ulnar dissociation following the Darach procedure).

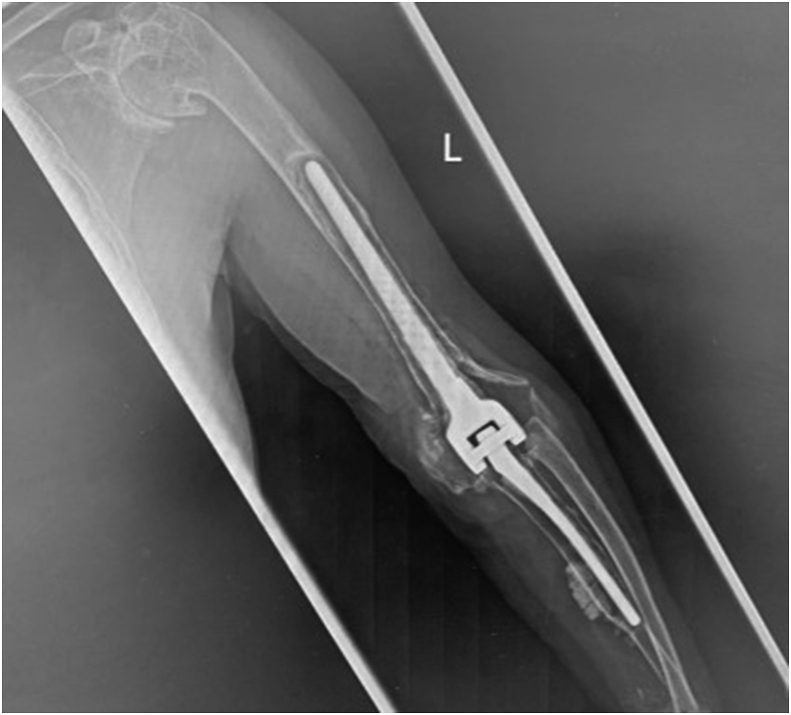

Fig. 3.

Lateral plain radiograph of the elbow, showing the potential humeral perforation, implant loosening, distal humeral posterior cortical breach, and olecranon dissociation.

Fig. 4.

Lateral plain radiograph of the elbow, showing the ulnar perforation, implant loosening, deep flexor compartment cement mass, dissociative longitudinal failure of the proximal ulna, absent proximal radioulnar joint, distal humeral posterior cortical breach, and olecranon dissociation.

The olecranon was fractured and displaced with loss of bone volume consistent with the elbow extension weakness and lag. The mid shaft ventral cortex of the ulna was penetrated with complete failure of the proximal ventral cortex and proximal migration of the coronoid.

A custom-made implant (Lima Promade, Udine, Italy) was planned to liberate the adjacent shoulder joint and restore the overall reaching function of the upper limb. Specific elements of the surface of the implants were roughened with trabecular titanium for improved bone apposition, integration and healing. Autogenous bone graft was impacted to fill the irregular voids. The diaphysis of the humerus was protected with an intramedullary stem bridging between the shoulder and elbow joints to avoid a central stress riser and preserve muscular attachments to the humerus (Fig. 5). The distal part of the ulnar implant was tapered to fit the narrow distal ulna medullary canal (Fig. 6). Distal cement fixation was planned to optimise rotational stability in order to facilitate proximal bone on-growth.

Fig. 5.

Anteroposterior view of the shoulder and lateral view of the (flexed) elbow at the third week postoperatively.

Fig. 6.

Lateral radiograph of the elbow showing the reconstruction of the proximal ulna using a segment of the greater tuberosity of the humerus, the distal cementation for rotational control of the implant, and the ‘fit-fill’ principle of the proximal design.

21. Postoperative aftercare

The postoperative aftercare in complex revision depends on the strength of the reconstructed extensor mechanism and the initial stability of the bone-implant construct. Immediate postoperative management is determined by the needs of skin wound healing, reduction in distal limb oedema, maintenance of hand function, and protection of the ulnar nerve. Flexion and pronosupination are encouraged with gravity eliminated, limiting flexion according to the security of the triceps construct (with the overall flexion limit determined at skin closure). Circumferential bandaging should be used with great care if at all, to avoid this becoming a tourniquet and promoting distal oedema and pain. Isometric activation of the shunt muscles (including biceps and triceps) will help to increase the stability of the joint and, promote restoration of the neural feedback mechanisms of motor control.22 These concepts can be built into the mid-term rehabilitation (between skin healing and triceps healing: 3 weeks to 3 months), using functional rehabilitation in short lever arm activities rather than formal physiotherapy-based strengthening. Here, the concept that the shoulder and elbow are the ‘servants of the hand’ may have a role: rehabilitation is driven by hand competencies, and the elbow and shoulder ‘simply’ follow the hand in its tasks. Once implant-bone stability has been achieved (the absence of symptoms of failure of osseo-integration, and not usually earlier than 3 months after surgery) weight-bearing and load-sharing in long lever arm activities can be introduced, according to the patients' goals and needs.

High impacts and forces should generally be avoided. However, the recommendation of avoiding more than 2 kg of compression or distraction load has not been supported by biomechanical studies. Up to 40% of patients with elbow replacement perform activities which are “excessively demanding” for TER despite receiving relevant advice.23

22. Conclusion

The longevity of TER will continue to improve with evolving designs and improved understanding of the biomechanics of the elbow. Meanwhile R-TER still poses a significant challenge as the failed TER often presents with multiple issues as discussed. The multifactorial nature of the failing TER requires careful appreciation of the patient, their environment and functional goals, and a methodical approach to the structural assessment adhering to simple principles.

References

- 1.Geurts E.J., Viveen J., van Riet R.P., Kodde I.F., Eygendaal D. Outcomes after revision total elbow arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019 Feb;28(2):381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung E.V., O'Driscoll S.W. Total elbow prosthesis loosening caused by ulnar component pistoning. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007 Jun;89(6):1269–1274. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Regal S., Evans P.J. Coronoid impingement causing early failure of total elbow arthroplasty. Journal of Hand Surgery Global Online. 2020;2(5):312–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsg.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duquin T.R., Jacobson J.A., Schleck C.D., Larson D.R., Sanchez-Sotelo J., Morrey B.F. Triceps insufficiency after the treatment of deep infection following total elbow replacement. Bone Joint Lett J. 2014 Jan;96-B(1):82–87. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B1.31127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee B.P., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Polyethylene wear after total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005 May;87(5):1080–1087. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franck H., Gottwalt J. Peripheral bone density in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2009 Oct;28(10):1141–1145. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amirfeyz R., Stanley D. Allograft-prosthesis composite reconstruction for the management of failed elbow replacement with massive structural bone loss: a medium-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011 Oct;93(10):1382–1388. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B10.26729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amin A., Suresh S., Sanghrajka A. Custom-made endoprosthetic reconstruction of the distal humerus for non-tumorous pathology. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:446–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henrichs M.P., Liem D., Gosheger G. Megaprosthetic replacement of the distal humerus: still a challenge in limb salvage. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019 May;28(5):908–914. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung E.V., O'Driscoll S.W. Total elbow prosthesis loosening caused by ulnar component pistoning. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007 Jun;89(6):1269–1274. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regal S., Evans P.J. Coronoid impingement causing early failure of total elbow arthroplasty. Journal of Hand Surgery Global Online. 2020;2(5):312–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsg.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kho J.Y., Adams B.D., O'Rourke H. Outcome of semi-constrained total elbow arthroplasty in posttraumatic conditions with analysis of bushing wear on stress radiographs. Iowa Orthop J. 2015;35:124–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleager K.E., Cheung E.V. The "anconeus slide": rotation flap for management of posterior wound complications about the elbow. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011 Dec;20(8):1310–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zampeli F., Spyridonos S., Fandridis E. Brachioradialis muscle flap for posterior elbow defects: a simple and effective solution for the upper limb surgeon. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019 Aug;28(8):1476–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez-Sotelo J., Morrey B.F. Surgical techniques for reconstruction of chronic insufficiency of the triceps. Rotation flap using anconeus and tendo achillis allograft. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002 Nov;84(8):1116–1120. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b8.12902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sneftrup S.B., Jensen S.L., Johannsen H.V., Søjbjerg J.O. Revision of failed total elbow arthroplasty with use of a linked implant. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006 Jan;88(1):78–83. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B1.16446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reilly P., Rees J., Carr A.J. An aid to removal of cement during revision elbow replacement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006 Mar;88(2):231. doi: 10.1308/003588406X98531h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg S.H., Cohen M.S., Young M., Bradnock B. Thermal tissue damage caused by ultrasonic cement removal from the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005 Mar;87(3):583–591. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malone A.A., Sanchez J.S., Adams R., Morrey B. Revision of total elbow replacement by exchange cementing. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012 Jan;94(1):80–85. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B1.26004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spormann C., Achermann Y., Simmen B.R. Treatment strategies for periprosthetic infections after primary elbow arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012 Aug;21(8):992–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Streubel P.N., Simone J.P., Morrey B.F., Sanchez-Sotelo J., Morrey M.E. Infection in total elbow arthroplasty with stable components: outcomes of a staged surgical protocol with retention of the components. Bone Joint Lett J. 2016 Jul;98-B(7):976–983. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.98B7.36397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michielsen M.E., Selles R.W., van der Geest J.N. Motor recovery and cortical reorganization after mirror therapy in chronic stroke patients: a phase II randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabilitation Neural Repair. 2011;6(3):223–233. doi: 10.1177/1545968310385127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barlow J.D., Morrey B.F., O'Driscoll S.W., Steinmann S.P., Sanchez-Sotelo J. Activities after total elbow arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013 Jun;22(6):787–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]