Abstract

Hsp110s are unique and essential molecular chaperones in the eukaryotic cytosol. They play important roles in maintaining cellular protein homeostasis. Candida albicans is the most prevalent yeast opportunistic pathogen that causes fungal infections in humans. As the only Hsp110 in Candida albicans, Msi3 is essential for the growth and infection of Candida albicans. In this study, we have expressed and purified Msi3 in nucleotide-free state and carried out biochemical analyses. Sse1 is the major Hsp110 in budding yeast S. cerevisiae and the best characterized Hsp110. Msi3 can substitute Sse1 in complementing the temperature-sensitive phenotype of S. cerevisiae carrying a deletion of SSE1 gene although Msi3 shares only 63.4% sequence identity with Sse1. Consistent with this functional similarity, the purified Msi3 protein shares many similar biochemical activities with Sse1 including binding ATP with high affinity, changing conformation upon ATP binding, stimulating the nucleotide-exchange for Hsp70, preventing protein aggregation, and assisting Hsp70 in refolding denatured luciferase. These biochemical characterizations suggested that Msi3 can be used as a model for studying the molecular mechanisms of Hsp110s.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12192-021-01213-5.

Keywords: Hsp110, Hsp70, Molecular chaperones, Protein folding, Protein homeostasis

Introduction

As one of the leading causes of hospital-acquired infections, the yeast opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans can cause disseminated bloodstream infections with mortality rates above 40% (Costa-de-Oliveira and Rodrigues 2020; Lohse et al. 2018). Although C. albicans is usually a commensal organism for healthy people (Calderone and Fonzi 2001; Odds 1987), it can cause serious infections for critically ill or immunocompromised individuals, such as patients with AIDS, cancers, organ transplants, and implants (Dadar et al. 2018; Kirkpatrick 1994; Sherrington et al. 2018). However, treatment for C. albicans infections is limited to a small number of marginally effective antifungal drugs (Salazar et al. 2020). More importantly, a dramatic rise in resistance to these available antifungal drugs complicates the treatment (Berman and Krysan 2020). New treatment options for treating this pathogen with novel modes of action are urgently needed.

Due to their essential role in maintaining eukaryotic protein homeostasis (proteostasis), 110 kDa heat shock proteins (Hsp110s) play an essential role in the survival and growth of yeast pathogens including C. albicans (Cho et al. 2003; Nagao et al. 2012; Yakubu and Morano 2018). As the only Hsp110 in C. albicans, Msi3 is essential for both the growth and infection of C. albicans (Cho et al. 2003; Nagao et al. 2012; Yakubu and Morano 2018). Hence, Hsp110s represent a promising target for the design of novel and efficient treatments for infections caused by C. albicans. However, finding specific and potent inhibitors for Hsp110s has been limited by a lack of understanding of the molecular mechanism of Hsp110 chaperone activity. So far, only one small molecule inhibitor has been reported for Hsp110s (Gozzi et al. 2020). A better understanding of the molecular mechanism of Hsp110 chaperone activity will yield crucial insights regarding how to target this essential chaperone in order to develop novel and efficient treatments for yeast infections.

Hsp110s are a unique class of molecular chaperones that are ubiquitously present in the cytosol of eukaryotes (Dragovic et al. 2006; Easton et al. 2000; Lee-Yoon et al. 1995; Raviol et al. 2006b; Shaner and Morano 2007; Yakubu and Morano 2018). They play an essential role in maintaining proteostasis. Hsp110s achieve this important role alone or in conjunction with Hsp70s, another essential class of molecular chaperones that play key roles in virtually all known processes in maintaining proteostasis (Balchin et al. 2016; Bukau et al. 2006; Fernandez-Fernandez and Valpuesta 2018; Liu et al. 2020; Mayer and Bukau 2005; Pobre et al. 2019; Young 2010). Thus, Hsp110s are both chaperones by themselves and co-chaperones for Hsp70s. Hsp110s by themselves have potent chaperone activity in preventing aggregation of denatured proteins, even more efficient than Hsp70s (Goeckeler et al. 2002; Mattoo et al. 2013; Oh et al. 1997). However, they lack the hallmark activity of Hsp70s in assisting protein folding directly. A number of studies suggested that Hsp110s participate in almost all the processes that are associated with cytosolic Hsp70s including de novo protein folding and refolding under stress, protein transportation into the endoplasmic reticulum, solubilizing protein aggregates, and protein degradation (Albanese et al. 2006; Easton et al. 2000; Fan et al. 2007; Gao et al. 2015; Goeckeler et al. 2002; Hrizo et al. 2007; Kandasamy and Andreasson 2018; Liu et al. 1999; Mandal et al. 2010; Mattoo et al. 2013; Moran et al. 2013; O'Driscoll et al. 2015; Rampelt et al. 2012; Ravindran et al. 2015; Shaner and Morano 2007; Shaner et al. 2005; Shorter 2011; Torrente and Shorter 2013; Yakubu and Morano 2018; Yam et al. 2005). Besides the unique high activity in preventing protein aggregation, Hsp110s function as the major nucleotide-exchange factors (NEFs) for the cytosolic Hsp70s, facilitating the exchange of ADP for ATP in Hsp70s after ATP hydrolysis (Andreasson et al. 2008a; Bracher and Verghese 2015; Dragovic et al. 2006; Hendrickson and Liu 2008; Raviol et al. 2006b).

Although Hsp110s are crucial for eukaryotic proteostasis, the exact cellular roles of Hsp110s are poorly defined due to a lack of biochemical and structural understanding. Hsp110s share the same domain organization as Hsp70s (Easton et al. 2000; Liu and Hendrickson 2007; Liu et al. 2020; Shaner and Morano 2007). Both have two functional domains: a nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) at N-terminus and a substrate-binding domain (SBD) at the C-terminus. For Hsp70s, each domain has an essential intrinsic activity (Bukau et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2020; Mayer and Bukau 2005; Mayer and Gierasch 2019; Young 2010). The NBD binds ATP or ADP and hydrolyzes bound ATP to ADP. The SBD binds hydrophobic segments of polypeptides in an extended conformation, normally only found in unfolded proteins. Connecting these two functional domains is a short inter-domain linker. Hsp110s are larger in size due to an insertion in SBD and a C-terminal extension. However, both these extra segments are dispensable for function (Liu and Hendrickson 2007; Oh et al. 1999; Shaner et al. 2004). The ATP binding is essential for the chaperone activity and NEF activity of Hsp110s (Andreasson et al. 2008b; Bracher and Verghese 2015; Mattoo et al. 2013; Polier et al. 2008; Shaner et al. 2004; Yakubu and Morano 2018). However, the properties of the two intrinsic activities largely remain a mystery for Hsp110s.

Our current biochemical and structural understanding of Hsp110s is mainly based on studies on Sse1, an Hsp110 from yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Andreasson et al. 2008b; Dragovic et al. 2006; Goeckeler et al. 2008; Goeckeler et al. 2002; Liu and Hendrickson 2007; Mukai et al. 1993; Polier et al. 2008; Raviol et al. 2006b; Sadlish et al. 2008; Schuermann et al. 2008; Shaner et al. 2006; Shaner et al. 2004; Shorter 2011; Xu et al. 2012; Yakubu and Morano 2018). There are two highly conserved and functionally overlapped Hsp110s in S. cerevisiae, Sse1 and Sse2 (Mukai et al. 1993; Trott et al. 2005). Together, these two Hsp110s are essential for yeast viability. Previously, we have solved the first X-ray crystal structure of a full-length Hsp110 using Sse1 (Liu and Hendrickson 2007). In addition, two structural studies on Sse1 in complex with Hsp70s have revealed the molecular mechanism of its nucleotide-exchange activity (Polier et al. 2008; Schuermann et al. 2008). Although the sequence identities between Sse1 and Hsp70s are low, the overall conformation is highly similar (Liu and Hendrickson 2007; Polier et al. 2008; Schuermann et al. 2008), confirming that Hsp110s and Hsp70s are undoubtedly relatives. In all these Sse1 structures, Sse1 is in the ATP-bound conformation. No structure is available for either the ADP-bound or nucleotide-free state although drastic conformational difference between these states and the ATP-bound state has been suggested (Andreasson et al. 2008b; Dragovic et al. 2006; Goeckeler et al. 2008; Kumar et al. 2020; Liu and Hendrickson 2007; Shaner et al. 2004; Xu et al. 2012; Yakubu and Morano 2018).

Msi3, the only and essential Hsp110 in C. albicans, shares 63.4% sequence identity with Sse1. Msi3 has been shown to be able to rescue the temperature-sensitive phenotype of a SSE1 deletion strain, suggesting the functional conservation between Sse1 and Msi3 (Cho et al. 2003). To understand the molecular mechanism of the essential chaperone activity of Msi3, we have expressed and purified Msi3 and carried out biochemical analyses. Consistent with the functional conservation, our results suggested that Msi3 shares a similar biochemical and chaperone activity as Sse1. Thus, like Sse1, Msi3 can also be used as a general model Hsp110 to study the chaperone activity of Hsp110s.

Materials and methods

Yeast growth test and site-directed mutagenesis

The MSI3 ORF was amplified from the genomic DNA of C. albicans and inserted into the pRS313 yeast vector. The endogenous promoter of SSE1 was inserted right in front of the MSI3 ORF. Thus, the resulting pRS313-MSI3 plasmid has the MSI3 gene under the control of the endogenous promoter of SSE1. Mutations in MSI3 were introduced into the pRS313-MSI3 plasmid using the QuikChange Lightning Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Growth tests of MSI3 and mutations in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae were carried out as described before (Liu and Hendrickson 2007). Briefly, the SSE1 deletion strain used was YPL106C BY4742 (MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 trp1Δ1 sse1Δ) (ordered from ATCC). After transforming into this yeast strain, fresh transformants were spotted onto agar plates containing yeast minimum media lacking histidine. Growth tests were carried out with incubation at 41 °C for 3 to 4 days with a control growth done at 30 °C.

Protein expression and purification

To express Msi3 in bacteria for purification, we cloned the MSI3 ORF into the pSMT3 plasmid (Mossessova and Lima 2000), an E. coli expression vector. The pSMT3 plasmid is a generous gift from Dr. Christopher Lima (the Sloan Kettering Institute). The expression of Msi3 was carried out in the Novagen’s Rosetta2(DE3)pLysS strain (MilliporeSigma). After transformation, fresh transformants were inoculated in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium in the presence of kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml) and grew at 37 °C until O.D. 600 reached around 0.6. Then, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM and the culture was shifted to 18 °C for induction. Cells were harvested after induction for 6 h or overnight. The cell pellet was resuspended in Lysis buffer (25 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM TCEP). The suspension was sonicated, clarified by centrifugation, and then loaded onto a 5 ml HisTrap column that had been pre-equilibrated with Lysis buffer. The column was washed extensively with Lysis buffer, Lysis buffer with 200 μM ATP and 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, Lysis buffer with 300 mM NaCl, and Lysis buffer with 30 mM imidazole to remove contaminations especially Hsp70s from E. coli. After eluting with a linear gradient of 30–240 mM imidazole, the fractions containing pure Smt3-Msi3 fusion protein were pooled and dialyzed in Lysis buffer. To remove the Smt3 tag, Ulp1 protease was added to the Smt3-Msi3 fusion protein during dialysis and incubated at room temperature for one overnight. The resulting Msi3 protein was separated from the Smt3 tag with the 6×His tag at the N-terminus on a second HisTrap column. The Msi3 protein was mainly in the flowthrough of this second HisTrap column. The flowthrough of the second HisTrap column was dialyzed in a buffer containing 25 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT to remove any nucleotide bound to Msi3. Msi3 was further purified on a 5 ml HiTrap Q column pre-equilibrated with Q Loading buffer (25 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT) and then was eluted with a linear gradient of 50–600 mM NaCl. The last step of purification was Superdex 200 26/600 using a buffer containing 25 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT. The purified Msi3 protein was concentrated to more than 10 mg/ml and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen before storing in − 80 °C freezer. All the columns are from GE Healthcare Life Sciences.

The full-length Ssa1 protein was expressed and purified from yeast Pichia pastoris strain GS115 as described previously with modifications (Wegele et al. 2003). The P. pastoris strain expressing Ssa1 was a generous gift from Dr. Johannes Buchner (Technical University of Munich). Briefly, after breaking open yeast with Avestin Emulsiflex, the cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 rpm, and then, the supernatant was applied onto a HiTrap Q column. The fractions containing Ssa1 were further subjected to ammonium sulfate precipitation. The pellets from ammonium sulfate precipitation were dissolved in solubilization buffer (25 mM Hepes-KOH, pH7.5, 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4, and 1 mM DTT) and then further purified on a butyl-Sepharose column. After dialyzed in Binding buffer (25 mM Hepes, pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, and 1 mM DTT), the Ssa1 Proteins were mixed directly with a 3 ml ATP agarose resins (Sigma). The resins were washed extensively with Binding buffer and then the bound Ssa1 protein was eluted with 5 mM ATP in Binding buffer. The Ssa1 protein was concentrated to > 10 mg/ml and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

The firefly luciferase was cloned, expressed, and purified in a similar way as that of Msi3 except that the last sizing column was not used.

Fluorescence polarization assay for ATP binding

To determine the binding affinity of Msi3 for ATP, fluorescence polarization (FP) measurements were performed using a fluorescence-labeled ATP, N6-(6-amino)hexyl-ATP-5-FAM (ATP-FAM) (Jena Bioscience, Jena, Germany). Serial dilutions of Sse1 or Msi3 proteins were prepared and incubated with ATP-FAM (a final concentration of 20 nM) in buffer A (25 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 150 mM KCl, 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT) for 1 h at room temperature to allow binding to reach equilibrium. Then, FP measurements were carried out on a Beacon 2000 instrument (Invitrogen). FP values were expressed in millipolarization (mP) units. Binding data analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software and fitted to a one-site binding equation to calculate dissociation constants (Kd). All the biochemical assays were repeated at least three times with more than two independent protein purifications.

Limited proteolysis analysis for ATP-induced conformational changes

The assay was carried out as described previously for the Sse1 protein with some modifications (Liu and Hendrickson 2007). Briefly, Msi3 proteins were diluted to 1 mg/ml using buffer A. An equal volume of trypsin (20 μg/ml) or proteinase K (20 μg/ml) was mixed with the Msi3 protein in the presence of 2 mM ATP or 2 mM ADP or in the absence of any nucleotide. The reaction was incubated at 25 °C for 30 min. PMSF was added to a final concentration of 1 mM to stop the digest reactions. The Ssa1 alone reactions were performed in an almost identical way as that of Msi3. For the reactions with both Msi3 and Ssa1, Msi3 and Ssa1 were mixed at 1:1 molar ratio and incubated on ice for 30 min in the presence of 2 mM ATP or 2 mM ADP or in the absence of nucleotide. Then, the digests with either trypsin or proteinase K were carried in the same way as Msi3 alone. After adding SDS sample buffer, each reaction was loaded on to 15% SDS-PAGE gels and visualized with Coomassie staining.

Preventing aggregation assay

To analyze the holdase activity, purified firefly luciferase was used as a model substrate. The aggregation of firefly luciferase in the presence of Msi3 was monitored using UV absorbance at 320 nm during the incubation at 42 °C in buffer B (25 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 150 mM KCl, 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, and 2 mM DTT). The final concentration of luciferase was kept at 750 nM for all the reactions. A serial of ratios of Msi3 to firefly luciferase were tested. Luciferase alone was used as a control. For the reactions with ATP, ATP was included at a final concentration of 3 mM.

The NEF activity assay

The NEF activity was measured using the aforementioned ATP-FAM. First, a complex of Ssa1 and ATP-FAM was formed by incubating 1 μM Ssa1 with 20 nM ATP-FAM in buffer A for 1 h on ice. Then, this complex was rapidly mixed with 1 μM Msi3 protein in the presence or absence of 50 μM of ATP at 25 °C, and the decreases in fluorescent polarization over time were recorded on a Beacon 2000 instrument (Invitrogen). Fifty micromolars ATP alone was used as a control.

Luciferase refolding assay using Ssa1 and Ydj1

The assay was performed similarly as previous publications with modifications (Dragovic et al. 2006; Polier et al. 2008). Briefly, purified firefly luciferase was diluted with buffer B to a final concentration of 110 nM in the presence of 30 μM Ssa1. Luciferase was denatured by incubating at 42 °C for 15 min. Refolding reactions were carried out by diluting the denatured luciferase into a reaction mixture containing 30 μM Ssa1, 4 μM Ydj1, and Msi3 in buffer B. After incubating at room temperature for 15 and 30 min, luciferase activities were measured in a luminometer (Berthold LB9507) by mixing 2 μl of refolding reactions with 50 μl of luciferase substrate (Promega). Various concentrations of Msi3 were tested. Relative luciferase activities were calculated by setting the activity of the unheated luciferase as 100%.

Results

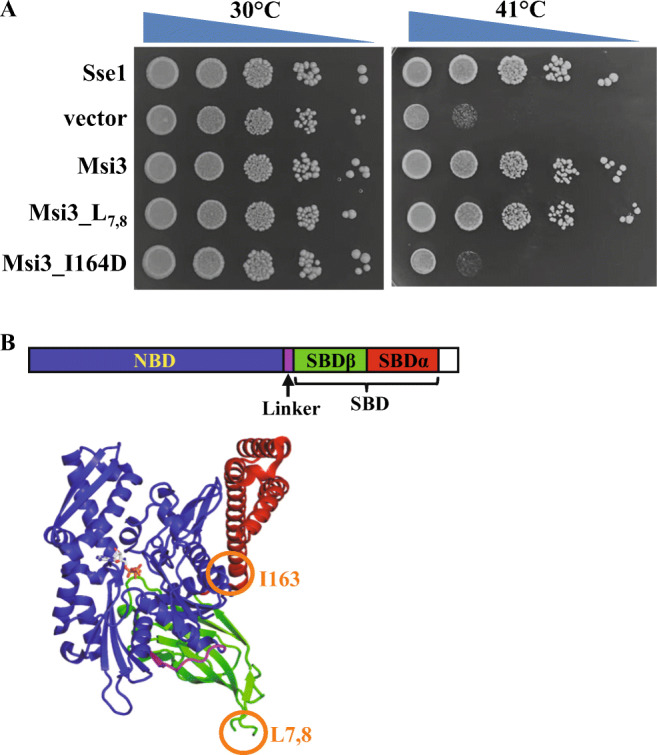

Msi3, the essential Hsp110 in Candida albicans, is functionally similar as Sse1

To characterize the molecular mechanism of Msi3, we first reproduced the previously published result that Msi3 can functionally substitute Sse1 using our yeast strain carrying a SSE1 deletion, YPL106C BY4742. We have cloned the MSI3 ORF from the genomic DNA of C. albicans (a generous gift from Dr. Ronda J. Rolfes, Department of Biology, Georgetown University) and replaced the SSE1 ORF using MSI3 on the pRS313 plasmid. Thus, the MSI3 ORF is under the control of the endogenous promoter of SSE1. Consistent with the previously published results (Cho et al. 2003), at 41 °C, the stress temperature, yeast carrying MSI3 grew almost like that carrying SSE1 although the colonies were slightly smaller for MSI3 than those of SSE1 (Fig. 1A). Previously, we have published the first crystal structure of Sse1 in complex with ATP and this structure revealed that Ile163, a residue on the NBD, mediates an essential contact between NBD-SBD to maintain the ATP-bound conformation (Fig. 1B) (Liu and Hendrickson 2007). Mutating Ile163 to Asp abolishes the chaperone activity of Sse1. To further test the functional conservation between Msi3 and Sse1, we made the analogous mutation in Msi3, I164D (Supplementary Figure 1). As shown in Fig. 1A, I164D completely abolished the growth of yeast at 41 °C. Moreover, previous studies suggested that the Hsp110-specific insertion in the SBD is not essential for the chaperone activity of Sse1 (Liu and Hendrickson 2007; Oh et al. 1999; Shaner et al. 2004). In the Sse1 structure, this insertion forms L7,8, a loop between two β strands (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Figure 1). We deleted the analogous loop in Msi3 and named it Msi3_ L7,8. Consistent with the Sse1 results, yeast carrying Msi3_ L7,8 grew as well as the wild-type Msi3 (Fig. 1A). Thus, these mutational analyses further supported the functional conservation between Msi3 and Sse1.

Fig. 1.

Msi3 is functionally similar as Sse1. A Growth test on Msi3 and mutations. Serial dilutions of yeast were dropped on plates and incubated at 41 °C and 30 °C (control). B Domain organization (upper panel) and structure (bottom panel) of Sse1. The position of Ile164 and L7,8 are highlighted with orange circles

Expression and purification of the nucleotide-free Msi3 protein

To characterize the biochemical properties of Msi3, we have cloned it into the pSMT3 vector (Mossessova and Lima 2000), an E. coli expression vector. Our induction tests demonstrated that Msi3 expressed well in the Novagen’s Rosetta2(DE3)pLysS strain (MilliporeSigma) (Supplementary Figure 2A). Using the pSMT3 vector, Msi3 was expressed as a fusion protein with Smt3 at the N-terminus. At the extreme N-terminus is a 6xHis tag. The majority of the Smt3-Msi3 fusion protein was soluble and bound to Ni column efficiently (Supplementary Figure 2B). To get rid of Hsp70s from E. coli, we washed the column with a buffer containing ATP (lane W1 in Supplementary Figure 2B). After purified on a Ni column, the fusion protein was digested with the Ulp1 protease to remove the Smt3 tag (Supplementary Figure 2C). Then, the Smt3 tag was removed using a second Ni column (Supplementary Figure 2D). The resulting Msi3 protein was dialyzed extensively using a buffer containing EDTA to remove ATP. The Msi3 protein was further purified on a HiTrapQ column and Superdex 200 16/600 column (Supplementary Figure 2E and F). On the Superdex column, Msi3 formed primarily one peak. The resulting Msi3 protein is of high purity.

Msi3 binds ATP and changes conformation upon ATP binding

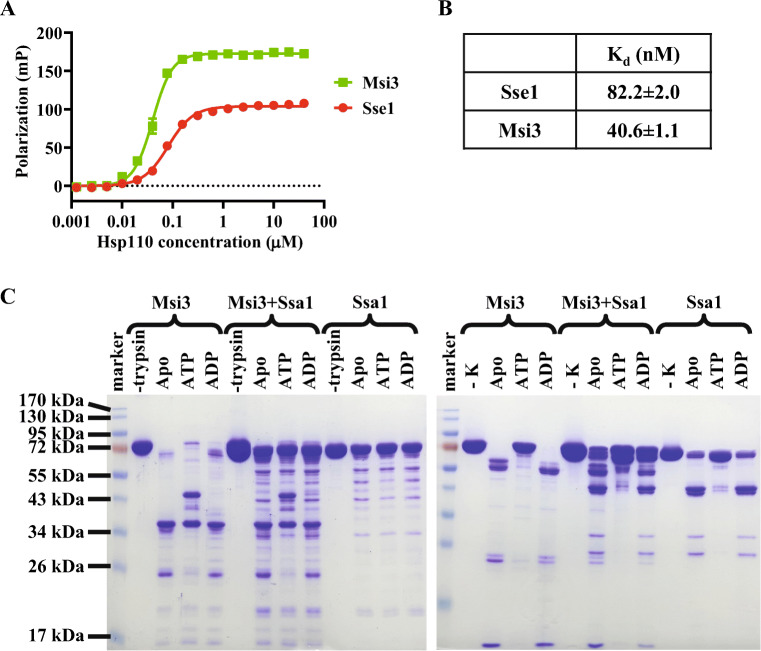

Sse1 binds ATP and ATP binding changes the conformation of Sse1 (Andreasson et al. 2008b; Garcia et al. 2017; Liu and Hendrickson 2007; Raviol et al. 2006a; Shaner et al. 2004). Thus, we first tested whether Msi3 binds ATP. To test ATP binding, we used N6-(6-amino)hexyl-ATP-5-FAM (ATP-FAM), a fluorescently labeled ATP. Consistent with previously published results (Garcia et al. 2017), Sse1 binds ATP-FAM with a high affinity using a fluorescence polarization assay (Fig. 2 A and B). When we tested Msi3, a similar high affinity for ATP-FAM was observed although the absolute values of fluorescence polarization for Msi3 are higher than those of Sse1. The higher polarization values suggest that Msi3 may have a different oligomerization state from Sse1 since the absolute values of fluorescence polarization are related to the molecular weight of the Hsp110 proteins.

Fig. 2.

ATP binds Msi3 with a high affinity and induces conformational changes in Msi3. A The ATP binding to Msi3 and Sse1 proteins determined using fluorescence polarization assay. ATP-FAM, a fluorescence-labeled ATP, was incubated with a serial dilution of the Hsp110 proteins. Fluorescence polarization was measured after binding reached equilibrium. B Dissociation constants (Kd) calculated from A. C The ATP-induced conformational changes in Msi3 revealed by limited protease digest using trypsin (left gel) or proteinase K (right gel). Msi3 proteins were treated with a low concentration of either trypsin or proteinase K (K) in the absence of nucleotide (Apo) or the presence of indicated nucleotides. The effect of forming complex with Ssa1 was tested in the presence of equal molar of Ssa1 (Msi3+Ssa1). Ssa1 protein alone (Ssa1) was used as controls. The Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels were used to visualize the digestion profiles

Next, we tested whether ATP binding induces conformational changes in Msi3 like Sse1. To do this, we carried out the limited proteolysis assay using trypsin and proteinase K. Together with a number of previous studies, our published limited trypsin digest analysis has revealed that Sse1 has two overall conformational states: the ATP-bound and ADP-bound/nucleotide-free (apo) states (Andreasson et al. 2008b; Kumar et al. 2020; Liu and Hendrickson 2007; Raviol et al. 2006a; Shaner et al. 2004). The ATP-bound state is more resistant to trypsin digest than the ADP-bound/apo state, consistent with the extensive NBD-SBD interfaces observed in the crystal structures of the ATP-bound Sse1 (Liu and Hendrickson 2007; Polier et al. 2008; Schuermann et al. 2008). In contrast, the ADP-bound/apo state has a reduced trypsin resistance, suggesting limited contacts between the NBD and SBD in this state. As shown in Fig. 2C, Msi3 is more resistant to both trypsin and proteinase K digests in the presence of ATP than either in the absence of nucleotide or when ADP was added. Due to the differences in cleavage specificity between trypsin and proteinase K, the digest patterns of Msi3 using these two proteases were different. Regardless of the different digest patterns, the susceptibility to trypsin and proteinase K digest in the absence of added nucleotide suggested that the purified Msi3 was mainly in the apo state, i.e., free of bound nucleotide. Besides a significant amount of intact protein, two major tryptic bands were observed in the presence of ATP: around 43 and 36 kDa (Fig. 2C, left panel). In contrast, in the absence of nucleotide or the presence of ADP, only one major tryptic band was observed around 36 kDa. These tryptic patterns of Msi3 were almost identical to those published for Sse1 (Liu and Hendrickson 2007). For Sse1, the corresponding bands were about 43 and 30 kDa, and were identified as the NBD and SBD, respectively. Due to the high sequence identity between Msi3 and Sse1 (Supplementary Figure 1), the corresponding tryptic bands at 43 and 36 kDa observed for Msi3 most likely also represent the NBD and SBD, respectively. Thus, in the presence of ATP, only the inter-domain linker is accessible for the trypsin digest whereas the NBD and SBD are not. In contrast, in the apo and ADP-bound states, the NBD became susceptible for the trypsin digest. Taken together, like Sse1, there are two overall conformational states for Msi3 depending on nucleotides and ATP most likely induces close NBD-SBD contacts in Msi3.

Msi3 has holdase activity

Several Hsp110s studied so far including Sse1 have shown a high chaperone activity in preventing protein aggregation, i.e. a holdase activity (Goeckeler et al. 2002; Mattoo et al. 2013; Muralidharan et al. 2012; Oh et al. 1997; Xu et al. 2012). We tested whether Msi3 has this chaperone activity using firefly luciferase as a model substrate. When heated at 42 °C, firefly luciferase denatures and aggregates. The luciferase aggregates scatter light due to their large sizes, which results in an increased apparent absorbance at wavelength 320 nm. As shown in Fig. 3A and Supplementary Figure 3A, Msi3 successfully prevented the aggregation of luciferase caused by 42 °C incubation in a concentration-dependent manner, supporting a holdase activity for Msi3. Furthermore, this holdase activity of Msi3 depends on ATP. In the absence of ATP, the aggregation levels of firefly luciferase when incubated with Msi3 were either comparable to or higher than that of firefly luciferase itself (Fig. 3B). ATP showed little influence on the aggregation of firefly luciferase alone as the aggregation levels in the presence of and in the absence of ATP were similar (Supplementary Figure 3B). The increased aggregation in the presence of Msi3 and in the absence of ATP was most likely due to the aggregation of Msi3 in the absence of ATP (Supplementary Figure 3C).

Fig. 3.

Msi3 prevents firefly luciferase from aggregation in an ATP-dependent manner. The aggregation of firefly luciferase in the presence of ATP (A) and absence of ATP (B). Firefly luciferase was incubated with Msi3 at 42 °C, and the aggregation was measured using absorbance at 320 nm (O.D. 320). The ratios of luciferase over the Msi3 chaperone were listed on the right for each panel

Msi3 functionally interacts with Ssa1, a classic Hsp70 in yeast

Sse1 has been shown to interact with Ssa1 in the presence of ATP and function as a NEF for Ssa1 (Bracher and Verghese 2015; Dragovic et al. 2006; Raviol et al. 2006b; Shaner et al. 2005; Yakubu and Morano 2018; Yam et al. 2005). Since Msi3 can functionally substitute Sse1 in supporting yeast growth, we hypothesized that Msi3 can interact with Ssa1 like Sse1. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed whether Msi3 has a NEF activity on Ssa1. First, we formed a Ssa1-ATP complex using ATP-FAM. This complex has a high polarization reading due to the large size of Ssa1. When regular ATP was added to this complex, ATP-FAM was slowly replaced by the regular ATP, which resulted in reduced polarization values over the time of incubation (Fig. 4A). Adding Sse1 in the absence of ATP has little effect on this complex. In contrast, adding Sse1 together with ATP drastically sped up the decrease of polarization (Fig. 4A), consistent with the published NEF activity of Sse1 (Dragovic et al. 2006; Raviol et al. 2006b). When Msi3 was tested in place of Sse1, a similar NEF activity was observed although slightly weaker than that of Sse1 at the same concentration (Fig. 4B). The slightly weaker NEF activity of Msi3 is consistent with the somewhat smaller colonies in our growth test described above (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 4.

Msi3 facilitated the nucleotide exchange for Ssa1. The NEF activity of Msi3 was compared with that of Sse1. A complex of Ssa1 and ATP-FAM was formed first. Then, Sse1 (A) or Msi3 (B) was added in combination with ATP or buffer to the pre-formed complex of Ssa1 and ATP-FAM. The release of bound ATP-FAM from Ssa1 was recorded over time. Buffer and ATP alone were used as controls

In addition, to test the effect of forming complex with Ssa1 on the conformation of Msi3, we carried out the limited proteolysis analysis on Msi3 in the presence of Ssa1 using trypsin and proteinase K as described above. As shown in Fig. 2C, addition of Ssa1 has little influence on the digest profiles of Msi3 after treating with either trypsin or proteinase K. Consistent with previous studies (Fung et al. 1996), ATP also induces conformational changes in Ssa1. Thus, when forming a complex with Ssa1, Msi3 most likely remains the same conformation as by itself. This is consistent with the observation that the Sse1 structure in the complex with Hsp70s is virtually identical to the Sse1 structure alone (Liu and Hendrickson 2007; Polier et al. 2008; Schuermann et al. 2008).

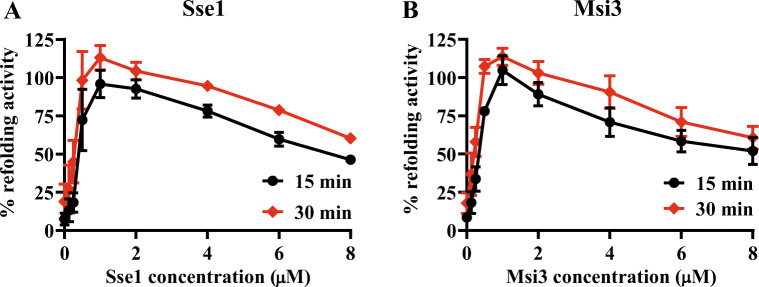

Msi3 facilitates Ssa1 in protein folding

Sse1 has been shown to assist Ssa1 in protein folding (Dragovic et al. 2006; Raviol et al. 2006b). To test whether Msi3 can substitute Sse1 in assisting Ssa1 in protein folding, we carried out a refolding assay using the heat-denatured firefly luciferase. In this assay, firefly luciferase was first denatured by incubating at 42 °C. Then, Ssa1, Ydj1, and Sse1/Msi3 were added to facilitate the refolding of the denatured luciferase. As shown in Fig. 5, Ssa1 and Ydj1 together can lead to 10–20% recovery of luciferase activity. Adding either Sse1 or Msi3 drastically increased luciferase activity to about 100%. Thus, Msi3 shares a similar activity as Sse1 in facilitating the refolding activity of the Ssa1-Ydj1 chaperone machinery.

Fig. 5.

Msi3 facilitates Ssa1 in protein folding. A, B Refolding of heat-denatured firefly luciferase by the Ssa1-Ydj1-Sse1 (A) and Ssa1-Ydj1-Msi3 (B) chaperone machinery

Discussion

In this study, we have expressed, purified, and carried out biochemical analyses on Msi3, the only Hsp110 in the pathogenic yeast C. albicans. As shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5, our biochemical data support that Msi3 shares almost identical biochemical properties as Sse1, an extensively studied model for Hsp110s. Thus, Msi3 can also be used as a model to study the biochemical, structural, and functional properties of Hsp110s in order to understand the molecular mechanism of Hsp110 chaperone activity. In our hands, Msi3 has a higher and more consistent expression than Sse1 in the E.coli expression system, which provides an attractive advantage for biochemical and structural analysis. In fact, we have obtained crystals of Msi3 and currently are in the process of optimizing the conditions for diffraction analysis. To express Sse1 and Msi3 in E. coli for purification, we have tried both BL21 and Rosetta strains, two commonly used strains for protein expression. Msi3 constantly showed high expression in Rosetta whereas little expression was detected in BL21 (Supplementary Figure 2A for Rosetta and data not shown for BL21). However, Sse1 only showed modest expression in BL21 and little expression in Rosetta. This expression advantage of Msi3 is especially useful for characterizing mutant proteins for dissecting the molecular mechanism of Hsp110s. Mutant proteins normally have lower expression than the wild-type proteins, which presents challenges for purification and biochemical analysis. For example, we had difficulties in expressing and purifying the Sse1 protein carrying the I163D mutation to get sufficient purity and amount. In contrast, we have successfully purified the Msi3 protein carrying the analogous I164D mutation. This allowed us to biochemically characterize this mutation (manuscript in preparation).

Importantly, Msi3 is indispensable for the infection of C. albicans (Cho et al. 2003; Nagao et al. 2012; Yakubu and Morano 2018). Some of the biochemical properties of Msi3 characterized in this study may be used to develop sensitive assays to screen for small molecule modulators targeting Msi3’s chaperone activity, such as the ATP binding (Fig. 2), preventing aggregation of luciferase (Fig. 3), NEF (Fig. 4), and refolding of heat-denatured luciferase (Fig. 5). Thus, these biochemical properties of Msi3 provide a solid groundwork for screening specific inhibitors for Msi3. These small molecule inhibitors could potentially yield novel and effective therapeutics for treating fatal C. albicans infections.

In addition, Msi3 can substitute Sse1 in supporting the growth of the SSE1 deletion strains of S. cerevisiae at elevated temperatures such as 41 °C in this study (Fig. 1A) (Cho et al. 2003). Consistent with this in vivo function, our biochemical analyses showed that Msi3 is able to facilitate the nucleotide-exchange for Ssa1 (Fig. 4) and assist Ssa1 in refolding the heat-denatured luciferase (Fig. 5) although maybe at a slightly lower level than that of Sse1. Thus, we can use this S. cerevisiae strain carrying MSI3 and deletion of SSE1 to characterize both the in vivo function of Msi3 mutants and the functional effect of the small molecule inhibitors of Msi3 instead of using C. albicans. Msi3 share 63.4% sequence identity with Sse1, and 59.5% with Sse2. Sse1 and Sse2 share 75.6% sequence identity. However, the presence of Sse2 is not able to rescue the temperature sensitive phenotype of the SSE1 deletion strains (Mukai et al. 1993). Since Msi3 can substitute Sse1 in supporting growth, it is possible that Msi3 may share more functional conservation with Sse1 than Sse2 although Sse2 shares higher sequence identity with Sse1 than Msi3 does.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 477 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Ronda J. Rolfes (Department of Biology, Georgetown University) for providing the genomic DNA of C. albicans. We thank Ms. Baoxiu Zhang for technical support and Mr. Liqing Hu and Justin Kidd for discussion.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH (R01GM098592 and R21AI140006 to Q.L.), and VETAR Award from VCU (to Q.L.).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ying Wang, Hongtao Li and Cancan Sun contributed equally to this work.

References

- Albanese V, Yam AY, Baughman J, Parnot C, Frydman J. Systems analyses reveal two chaperone networks with distinct functions in eukaryotic cells. Cell. 2006;124:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson C, Fiaux J, Rampelt H, Druffel-Augustin S, Bukau B. Insights into the structural dynamics of the Hsp110-Hsp70 interaction reveal the mechanism for nucleotide exchange activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16519–16524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804187105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson C, Fiaux J, Rampelt H, Mayer MP, Bukau B. Hsp110 is a nucleotide-activated exchange factor for Hsp70. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8877–8884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balchin D, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU. In vivo aspects of protein folding and quality control. Science. 2016;353:aac4354. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman J, Krysan DJ. Drug resistance and tolerance in fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18:319–331. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0322-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher A, Verghese J. The nucleotide exchange factors of Hsp70 molecular chaperones. Front Mol Biosci. 2015;2:10. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2015.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B, Weissman J, Horwich A. Molecular chaperones and protein quality control. Cell. 2006;125:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderone RA, Fonzi WA. Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:327–335. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho T, Toyoda M, Sudoh M, Nakashima Y, Calderone RA, Kaminishi H. Isolation and sequencing of the Candida albicans MSI3, a putative novel member of the HSP70 family. Yeast. 2003;20:149–156. doi: 10.1002/yea.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-de-Oliveira S, Rodrigues AG (2020) Candida albicans Antifungal Resistance and Tolerance in Bloodstream Infections: The Triad Yeast-Host-Antifungal. Microorganisms 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dadar M, Tiwari R, Karthik K, Chakraborty S, Shahali Y, Dhama K. Candida albicans - Biology, molecular characterization, pathogenicity, and advances in diagnosis and control - An update. Microb Pathog. 2018;117:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragovic Z, Broadley SA, Shomura Y, Bracher A, Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones of the Hsp110 family act as nucleotide exchange factors of Hsp70s. EMBO J. 2006;25:2519–2528. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton DP, Kaneko Y, Subjeck JR. The hsp110 and Grp1 70 stress proteins: newly recognized relatives of the Hsp70s. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2000;5:276–290. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2000)005<0276:THAGSP>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Q, Park KW, Du Z, Morano KA, Li L. The role of Sse1 in the de novo formation and variant determination of the [PSI+] prion. Genetics. 2007;177:1583–1593. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.077982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Fernandez MR, Valpuesta JM (2018) Hsp70 chaperone: a master player in protein homeostasis. F1000Res 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fung KL, Hilgenberg L, Wang NM, Chirico WJ. Conformations of the nucleotide and polypeptide binding domains of a cytosolic Hsp70 molecular chaperone are coupled. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21559–21565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Carroni M, Nussbaum-Krammer C, Mogk A, Nillegoda NB, Szlachcic A, Guilbride DL, Saibil HR, Mayer MP, Bukau B. Human Hsp70 Disaggregase Reverses Parkinson's-Linked alpha-Synuclein Amyloid Fibrils. Mol Cell. 2015;59:781–793. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia VM, Nillegoda NB, Bukau B, Morano KA. Substrate binding by the yeast Hsp110 nucleotide exchange factor and molecular chaperone Sse1 is not obligate for its biological activities. Mol Biol Cell. 2017;28:2066–2075. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e17-01-0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeckeler JL, Stephens A, Lee P, Caplan AJ, Brodsky JL. Overexpression of yeast Hsp110 homolog Sse1p suppresses ydj1-151 thermosensitivity and restores Hsp90-dependent activity. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2760–2770. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-04-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeckeler JL, Petruso AP, Aguirre J, Clement CC, Chiosis G, Brodsky JL. The yeast Hsp110, Sse1p, exhibits high-affinity peptide binding. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2393–2396. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozzi GJ, Gonzalez D, Boudesco C, Dias AMM, Gotthard G, Uyanik B, Dondaine L, Marcion G, Hermetet F, Denis C, Hardy L, Suzanne P, Douhard R, Jego G, Dubrez L, Demidov ON, Neiers F, Briand L, Sopková-de Oliveira Santos J, Voisin-Chiret AS, Garrido C. Selecting the first chemical molecule inhibitor of HSP110 for colorectal cancer therapy. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:117–129. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0343-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson WA, Liu Q. Exchange we can believe in. Structure. 2008;16:1153–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrizo SL, Gusarova V, Habiel DM, Goeckeler JL, Fisher EA, Brodsky JL. The Hsp110 molecular chaperone stabilizes apolipoprotein B from endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32665–32675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705216200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandasamy G, Andreasson C (2018) Hsp70-Hsp110 chaperones deliver ubiquitin-dependent and -independent substrates to the 26S proteasome for proteolysis in yeast. J Cell Sci 131 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick CH. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S14–S17. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(08)81260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Peter JJ, Sagar A, Ray A, Jha MP, Rebeaud ME, Tiwari S, Goloubinoff P, Ashish F, Mapa K. Interdomain communication suppressing high intrinsic ATPase activity of Sse1 is essential for its co-disaggregase activity with Ssa1. FEBS J. 2020;287:671–694. doi: 10.1111/febs.15045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Yoon D, Easton D, Murawski M, Burd R, Subjeck JR. Identification of a major subfamily of large hsp70-like proteins through the cloning of the mammalian 110-kDa heat shock protein. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15725–15733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Hendrickson WA. Insights into Hsp70 chaperone activity from a crystal structure of the yeast Hsp110 Sse1. Cell. 2007;131:106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XD, Morano KA, Thiele DJ. The yeast Hsp110 family member, Sse1, is an Hsp90 cochaperone. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26654–26660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Liang C, Zhou L. Structural and functional analysis of the Hsp70/Hsp40 chaperone system. Protein Sci. 2020;29:378–390. doi: 10.1002/pro.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse MB, Gulati M, Johnson AD, Nobile CJ. Development and regulation of single- and multi-species Candida albicans biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:19–31. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal AK, Gibney PA, Nillegoda NB, Theodoraki MA, Caplan AJ, Morano KA. Hsp110 chaperones control client fate determination in the hsp70-Hsp90 chaperone system. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1439–1448. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e09-09-0779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattoo RU, Sharma SK, Priya S, Finka A, Goloubinoff P. Hsp110 is a bona fide chaperone using ATP to unfold stable misfolded polypeptides and reciprocally collaborate with Hsp70 to solubilize protein aggregates. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:21399–21411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.479253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer MP, Bukau B. Hsp70 chaperones: cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:670–684. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4464-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer MP, Gierasch LM. Recent advances in the structural and mechanistic aspects of Hsp70 molecular chaperones. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:2085–2097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV118.002810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran C, Kinsella GK, Zhang ZR, Perrett S, Jones GW. Mutational analysis of Sse1 (Hsp110) suggests an integral role for this chaperone in yeast prion propagation in vivo. G3 (Bethesda) 2013;3:1409–1418. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.007112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossessova E, Lima CD. Ulp1-SUMO crystal structure and genetic analysis reveal conserved interactions and a regulatory element essential for cell growth in yeast. Mol Cell. 2000;5:865–876. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai H, Kuno T, Tanaka H, Hirata D, Miyakawa T, Tanaka C. Isolation and characterization of SSE1 and SSE2, new members of the yeast HSP70 multigene family. Gene. 1993;132:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90514-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan V, Oksman A, Pal P, Lindquist S, Goldberg DE. Plasmodium falciparum heat shock protein 110 stabilizes the asparagine repeat-rich parasite proteome during malarial fevers. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1310. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao J, Cho T, Uno J, Ueno K, Imayoshi R, Nakayama H, Chibana H, Kaminishi H. Candida albicans Msi3p, a homolog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sse1p of the Hsp70 family, is involved in cell growth and fluconazole tolerance. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012;12:728–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2012.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odds FC. Candida infections: an overview. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1987;15:1–5. doi: 10.3109/10408418709104444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Driscoll J, Clare D, Saibil H. Prion aggregate structure in yeast cells is determined by the Hsp104-Hsp110 disaggregase machinery. J Cell Biol. 2015;211:145–158. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201505104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh HJ, Chen X, Subjeck JR. Hsp110 protects heat-denatured proteins and confers cellular thermoresistance. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31636–31640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh HJ, Easton D, Murawski M, Kaneko Y, Subjeck JR. The chaperoning activity of hsp110. Identification of functional domains by use of targeted deletions. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15712–15718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pobre KFR, Poet GJ, Hendershot LM. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone BiP is a master regulator of ER functions: Getting by with a little help from ERdj friends. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:2098–2108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV118.002804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polier S, Dragovic Z, Hartl FU, Bracher A. Structural basis for the cooperation of Hsp70 and Hsp110 chaperones in protein folding. Cell. 2008;133:1068–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampelt H, Kirstein-Miles J, Nillegoda NB, Chi K, Scholz SR, Morimoto RI, Bukau B. Metazoan Hsp70 machines use Hsp110 to power protein disaggregation. EMBO J. 2012;31:4221–4235. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran MS, Bagchi P, Inoue T, Tsai B. A Non-enveloped Virus Hijacks Host Disaggregation Machinery to Translocate across the Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005086. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raviol H, Bukau B, Mayer MP. Human and yeast Hsp110 chaperones exhibit functional differences. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raviol H, Sadlish H, Rodriguez F, Mayer MP, Bukau B. Chaperone network in the yeast cytosol: Hsp110 is revealed as an Hsp70 nucleotide exchange factor. EMBO J. 2006;25:2510–2518. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadlish H, Rampelt H, Shorter J, Wegrzyn RD, Andreasson C, Lindquist S, Bukau B. Hsp110 chaperones regulate prion formation and propagation in S. cerevisiae by two discrete activities. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar SB, Simoes RS, Pedro NA, Pinheiro MJ, Carvalho M, Mira NP (2020) An Overview on Conventional and Non-Conventional Therapeutic Approaches for the Treatment of Candidiasis and Underlying Resistance Mechanisms in Clinical Strains. J Fungi (Basel) 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schuermann JP, Jiang J, Cuellar J, Llorca O, Wang L, Gimenez LE, Jin S, Taylor AB, Demeler B, Morano KA, Hart PJ, Valpuesta JM, Lafer EM, Sousa R. Structure of the Hsp110:Hsc70 nucleotide exchange machine. Mol Cell. 2008;31:232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner L, Morano KA. All in the family: atypical Hsp70 chaperones are conserved modulators of Hsp70 activity. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2007;12:1–8. doi: 10.1379/CSC-245R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner L, Trott A, Goeckeler JL, Brodsky JL, Morano KA. The function of the yeast molecular chaperone Sse1 is mechanistically distinct from the closely related hsp70 family. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21992–22001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313739200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner L, Wegele H, Buchner J, Morano KA. The yeast Hsp110 Sse1 functionally interacts with the Hsp70 chaperones Ssa and Ssb. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41262–41269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503614200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner L, Sousa R, Morano KA. Characterization of Hsp70 binding and nucleotide exchange by the yeast Hsp110 chaperone Sse1. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15075–15084. doi: 10.1021/bi061279k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington SL, Kumwenda P, Kousser C, Hall RA. Host Sensing by Pathogenic Fungi. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2018;102:159–221. doi: 10.1016/bs.aambs.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorter J. The mammalian disaggregase machinery: Hsp110 synergizes with Hsp70 and Hsp40 to catalyze protein disaggregation and reactivation in a cell-free system. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrente MP, Shorter J. The metazoan protein disaggregase and amyloid depolymerase system: Hsp110, Hsp70, Hsp40, and small heat shock proteins. Prion. 2013;7:457–463. doi: 10.4161/pri.27531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott A, Shaner L, Morano KA. The molecular chaperone Sse1 and the growth control protein kinase Sch9 collaborate to regulate protein kinase A activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2005;170:1009–1021. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.043109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegele H, Haslbeck M, Buchner J. Recombinant expression and purification of Ssa1p (Hsp70) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae using Pichia pastoris. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2003;786:109–115. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Sarbeng EB, Vorvis C, Kumar DP, Zhou L, Liu Q. The unique peptide substrate binding properties of 110 KDA heatshock protein (HSP110) determines its distinct chaperone activity. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:5661–5672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.275057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakubu UM, Morano KA. Roles of the nucleotide exchange factor and chaperone Hsp110 in cellular proteostasis and diseases of protein misfolding. Biol Chem. 2018;399:1215–1221. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2018-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam AY, Albanese V, Lin HT, Frydman J. Hsp110 cooperates with different cytosolic HSP70 systems in a pathway for de novo folding. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41252–41261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JC. Mechanisms of the Hsp70 chaperone system. Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;88:291–300. doi: 10.1139/O09-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 477 kb)