Short abstract

In shoulder osteoarthritis, the B2 glenoid presents challenges in treatment because of the excessive retroversion and posterior deficiency of the glenoid. Correction of retroversion and maintenance of a stable joint line with well-fixed implants are essential for the successful treatment of this deformity with arthroplasty. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty offers several key advantages in achieving this goal, including favorable biomechanics, a well-fixed baseplate, and proven success in other applications. Techniques such as eccentric reaming, bone grafting, and baseplate augmentation allow surgeons to tailor treatment to the patient’s altered anatomy. Eccentric reaming is favored for correction of small defects or mild version anomalies. Current trends favor bone grafting for larger corrections, though augmented components have shown early promise with the potential for expanded use. With overall promising results reported in the literature, reverse shoulder arthroplasty is a useful tool for treating older patients with B2 glenoid deformities.

Keywords: Reverse shoulder arthroplasty, B2 glenoid, biconcave glenoid, baseplate augmentation, glenoid bone grafting, eccentric glenoid reaming

Introduction

Asymmetric glenoid erosion is a well-known consequence of shoulder osteoarthritis that must be treated for successful shoulder arthroplasty. Walch et al. described 5 typical glenoid wear patterns in their landmark 1999 study, establishing a basis for modern classification and management. 1 The B2 subtype is characterized by the creation of a biconcave glenoid secondary to static posterior humeral subluxation and eccentric posterior erosion. 1 This type accounted for approximately 15% of the initial study group. 1 More recently, the B3 glenoid has been described as a possible progression of the B2 deformity, marked by severe posterior erosion that creates an excessively retroverted uniconcave glenoid.2,3 While more rare, the B3 glenoid poses similar challenges in operative treatment.

The etiology of the posteriorly eroded glenoid is multifactorial. Underlying skeletal anatomy, including excessive posterior glenoid version and a flat posterior acromial slope, can predict a tendency toward posterior glenoid erosion. 4 Altered glenohumeral biomechanics, whether from rotator cuff insufficiency or advanced osteoarthritis, can contribute to the progression of posterior glenoid wear. 5 Donohue et al. demonstrated an association between fatty infiltration of the rotator cuff and pathologic glenoid retroversion. 6 The degree of posterior glenoid bone loss poses challenges in establishing appropriate glenoid version during arthroplasty. Maintenance of suitable soft-tissue tension, adequate posterior shoulder stability, and well-fixed components in a deficient posterior glenoid also are concerns when considering arthroplasty for these patients.

Appropriate preoperative evaluation of glenoid wear is of paramount importance. Variations in morphology can alter operative plans, particularly when eccentric glenoid wear is encountered. Standard shoulder radiographs provide a starting point for evaluating glenohumeral wear and deformity. In the B2 glenoid, the axillary lateral view can show posterior humeral subluxation and glenoid biconcavity, but this view tends to exaggerate retroversion. 7 In addition, up to one-third of axillary lateral radiographs are unreadable for the purposes of classifying glenoid morphology. 8 Therefore, the workhorse of preoperative imaging is computed tomography (CT). The bony detail of CT scans allows close examination of bone loss, retroversion, and glenohumeral subluxation.7,9,10 Inaccuracies of measurement can occur when using 2-dimensional (2D) CT scans because of scapular rotation and beam alignment. 11 More recently, 3-dimensional (3D) CT scans have been used to further enhance the preoperative understanding of glenohumeral morphology and estimation of the volume of glenoid bone loss.12,13 The 3D CT scans also have the ability to subtract the scapula or humerus to allow more complete appreciation of the anatomy.

Recently, the preoperative 3D modeling software has allowed patient-specific planning to aid in glenoid baseplate placement. Virtual 3D models can be used to study a patient’s anatomy, simulate ideal component positioning, and develop patient-specific instrumentation to improve surgical technique.14–16 Early reports have described lower rates of component malposition and glenoid vault perforation with the use of these technologies.15–17 Drawbacks include prolonged time for creation, both for the 3D models and any patient-specific guides, and increased costs of surgery. 18 Overall, these technologies have shown early promise in aiding surgeons during difficult cases. Further research should investigate long-term outcomes, cost-benefit analysis, and the development of other technologically advanced planning options for RSA.

Historically, the B2 glenoid has created a significant challenge that has compromised the outcomes of arthroplasty. Levine et al. reported 63% satisfaction with hemiarthroplasty (HA) in patients with eccentric posterior glenoid wear. 19 At long-term follow-up 15 years later, the satisfaction rate fell to 12%, with a 31% revision rate. 20 The addition of glenoid reaming to an HA, termed “ream-and-run” technique, was initially thought to have potential in treating B2 glenoid arthritis. Results from a recent study with 2-year follow-up, however, showed only 23% improvement in Simple Shoulder Test scores and a 14% revision rate for patients with biconcave glenoids treated with ream-and-run procedures. 21 Among other problems, unbalanced medialization of the joint line with ream-and-run procedures can lead to soft-tissue laxity and residual posterior instability. 22 Walch et al. demonstrated a 20% glenoid loosening rate and 16% revision rate at 6 years for patients with a biconcave glenoid deformity treated with anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). 23 They also encountered postoperative posterior instability in 5.5% of patients, which correlated to excessive preoperative subluxation of the humeral head. Iannotti and Norris found that preoperative posterior humeral head subluxation predicted unfavorable outcomes, regardless of treatment with HA or TSA. 24 Recently, patient-specific instrumentation has shown promise in managing excessively retroverted glenoids in TSA. 25 Despite this, several features of RSA have made it a promising tool in treating patients with severe glenoid bone loss. The recent association between fatty infiltration of the rotator cuff and pathologic glenoid retroversion makes RSA an ideal surgical solution capable of addressing both issues simultaneously in a way that TSA cannot. 6 Even with a functional rotator cuff, RSA offers several key advantages when dealing with excessive posterior glenoid wear.

Role of Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty

Traditionally, RSA was performed for glenohumeral arthritis in elderly patients with rotator cuff insufficiency. Its use has continually expanded with improved implant design and favorable outcomes. 26 Lessons from revision shoulder arthroplasty have highlighted several benefits of RSA. Its semiconstrained nature confers inherent stability to the construct, while screw fixation of the glenoid baseplate allows easier incorporation of bone graft in cases of bone loss. 27

Klein et al. compared RSA operative techniques and clinical outcomes for normal and abnormal glenoid morphology in 216 patients, 17% of whom demonstrated posterior glenoid erosion with a minimum 2-year follow-up. 28 In their study, patients with eccentric glenoid erosion were more likely to receive intraoperative bone grafting or implantation of a large (36 or 40 mm) glenosphere than patients without glenoid defects. Despite this, the 2 groups had comparable clinical outcomes at 2 years.

Mizuno et al. evaluated the use of RSA for the treatment of osteoarthritis in 27 patients with biconcave glenoid deformity and intact rotator cuff function. 29 Selection criteria included age older than 70 years. They used asymmetric reaming to correct posterior glenoid defects and added bone graft in 37% of patients. Overall, they observed only 1 glenoid component failure in 54 months of follow-up, which presented as early loosening in a shoulder with a 15-mm central post. Most patients (93%) reported that they were “very satisfied” or “satisfied” with their outcomes. Functional outcomes were comparable to those of RSA for cuff tear arthropathy and TSA for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. The authors postulated that the semiconstrained nature of the RSA prevented residual posterior instability of the humerus, avoiding complications seen previously in TSA and HA for similar patients.

At our institution, we reviewed 49 patients with B2 or B3 glenoid deformities treated with primary RSA (unpublished data). The average age of the patients was 72 years, and 86% had an intact rotator cuff. A 36-mm glenosphere was used in all but 1 patient. Bone graft was used at the time of surgery in 92% of patients, including cortical graft (61.2%) and impaction grafting (30.6%) at the discretion of the operating surgeon. Metallic glenoid augmentation was used in 2 patients (4.1%). Minimum 2-year clinical and radiographic follow-up data were available for 25 patients with an average American Shoulder Elbow Surgeons shoulder score of 83.7 and Visual Analog Scale score of 0.9. Average range of motion at 2 years included forward elevation to 161°, external rotation to 40°, and internal rotation to 55°. To date, no mechanical failures have occurred and no reoperations have been required in this cohort. Our experience supports the data reported in the literature, including a general preference toward bone grafting, overall favorable 2-year outcomes, and a low revision rate at short-term follow-up after RSA for B2 deformities.

Traditionally, the role of RSA in cases of severe glenoid bone loss has been limited to elderly, low-demand patients.22,30,31 The semiconstrained nature of RSA components, while offering beneficial stability, also raises questions regarding implant longevity. 31 With limited follow-up available, several studies have focused on the incidence and implications of scapular notching to evaluate early implant performance.32–36 Despite these concerns, the benefits of stout glenoid baseplate fixation, easier bone grafting, and altered shoulder biomechanics have popularized RSA in treating elderly patients with substantial glenoid deformity.

Technical Considerations

While RSA technique often is patient-specific, several common challenges exist when managing a B2 glenoid deformity. Common pitfalls include excessive joint line medialization, inadequate glenoid baseplate fixation, and glenoid baseplate malposition. An overmedialized joint line with uncorrected glenoid bone loss alters soft-tissue tensioning across the glenohumeral joint, potentially compromising the strength and range of motion after RSA. It also can lead to inferomedial impingement that could cause inferior scapular notching, an osteolytic reaction that can compromise clinical outcomes.36,37 Notching can be minimalized by placing the baseplate inferiorly with an inferior tilt of 10° to 15°. 37 Judicious and minimalistic reaming, bone grafting, and attention to soft-tissue tension during surgery can mitigate the risk of overmedialization. With severe bone loss, the glenosphere may be upsized and/or lateralized to achieve appropriate balance.

Achieving excellent glenoid baseplate fixation, particularly in the central axis, is of extreme importance in establishing foundational stability in cases of glenoid bone loss. 28 Eccentric placement of glenoid components or altered screw trajectory to maximize bony purchase may be required in cases of distorted glenoid geometry. Klein et al. described an alternative “spine centerline” for placement of the central glenoid baseplate screw, passing through the center of the glenoid surface and into the axis of the scapular spine in patients with altered glenoid geometry. 28 If bone graft is required, sufficient screw length to engage native bone is necessary. Loss of graft fixation or inadequate graft incorporation can destabilize the entire glenoid component. Finally, inappropriate correction of glenoid version during RSA can lead to anterior component dislocation, particularly when the glenoid component is placed in more than 10° of retroversion. 38 Errors in glenoid component position or fixation may be more difficult to appreciate when glenoid anatomy is substantially altered.

Techniques for dealing with posterior glenoid bone loss and glenoid retroversion in RSA have evolved from solutions to the same problems in anatomic TSA. These include eccentric reaming, glenoid bone grafting, and augmented baseplate components.22,28,29,31,32,39–47 Such strategies can be used alone or in combination to combat posterior glenoid bone loss.

Eccentric Glenoid Reaming

Eccentric reaming refers to a technique whereby preferential reaming of the anterior “high-side” balances out a posteriorly eroded glenoid. 39 It is the simplest and most common way to correct small variations in version and to accommodate eccentric glenoid wear. By reaming the asymmetric glenoid to a flat surface, the implant is supported entirely by native bone without the need for grafting or augmentation. 46 The technique is simple and cost-efficient in the operating room, requiring only slight modification of a pivotal surgical step. Its effectiveness is limited, as the degree of posterior bone loss requires a proportionately large amount of anterior glenoid to be removed, thereby compromising overall remaining native glenoid bone stock. 39 A maximum of 15° to 18° of retroversion and 5 to 8 mm of posterior glenoid loss can be corrected in TSA due to limitations from peg perforation.22,37,39 No studies to date have reported on maximal limits specific to RSA. Unique to RSA, it is essential to maintain sufficient glenoid bone for baseplate fixation when eccentrically reaming.

While the volume of remaining bone can play a role in limiting eccentric reaming, the quality of bone also must be considered. In the B2 glenoid, the posteriorly subluxed humeral head articulates with the posterior glenoid. As a result, the posteroinferior quadrant contains substantially denser subchondral bone than the anterior glenoid hemisphere in accordance with Wolff’s law. 48 The net result of asymmetric reaming, therefore, creates a glenoid with a weak cancellous base anteriorly and a dense subarticular base posteriorly. Such variations after reaming can lead to unequal support of the glenoid baseplate, with the theoretical potential for catastrophic mechanical failure before complete osseointegration is achieved. 48

Small posterior glenoid defects with minimal retroversion, therefore, can be safely corrected by eccentric reaming. More pronounced defects or significant retroversion require the addition of bone graft or metal augments to maintain the joint line and ensure appropriate fixation.

Glenoid Bone Grafting

The use of bone grafting in B2 glenoids allows correction of glenoid version without excessive reaming, which effectively preserves glenoid bone stock. Grafting often follows a minimal amount of eccentric reaming, and the graft material is placed within the defect in conjunction with the baseplate. Rates of glenoid bone grafting in RSA are widely variable, ranging from 9% to 38%.41,49 Higher rates of grafting should be expected when treating patients with significant glenoid asymmetry. As a whole, bone grafting for glenoid defects in RSA has led to excellent clinical outcomes at short- and mid-term follow-up.42–45,50,51 While technically demanding in TSA, glenoid bone grafting in RSA is made easier by the more robust glenoid baseplate fixation with a either a long central peg or central screw along with multiple locking screws in the periphery. In addition, problems with graft incorporation seen in TSA may be alleviated by altered joint forces after RSA, where axial compression encourages incorporation.35,52

From a technical standpoint, the bone graft should be incorporated to a thickness that restores glenoid bone stock to that of the native joint. Both cortical structural and impaction cancellous techniques are reasonable (Figures 1 and 2). Excessive medialization can result in poor soft-tissue tension, prosthetic impingement, and instability after RSA. 34 It also can lead to inferior scapular notching, which can compromise implant longevity. Fixation of the graft to the native glenoid is achieved in conjunction with fixation of the glenoid baseplate. If using a central peg device, it should traverse the graft and gain purchase in at least 10 mm of native glenoid bone. 45 The ideal number and position of peripheral screws with glenoid grafting are not known and likely are patient-specific. Some surgeons advocate the use of 2 screws (superior and inferior) with a 4-hole baseplate to mitigate the risk of graft fracture, while others advocate 4-screw fixation for added stability when graft size permits.34,45,53

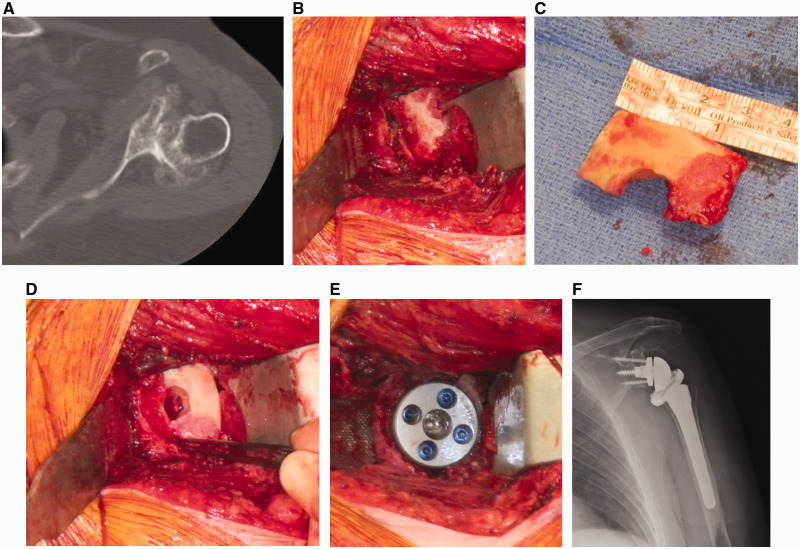

Figure 1.

A and B, Structural cortical bone grafting for posterior glenoid erosion can be accomplished by first creating a step cut in the glenoid surface with a bur. The graft can be fashioned from the humeral head and then placed in the defect. C and D, The humerus can then be prepared in standard fashion. E and F, After baseplate impaction, the peripheral locking screws in the baseplate provide fixation of the graft to the native glenoid.

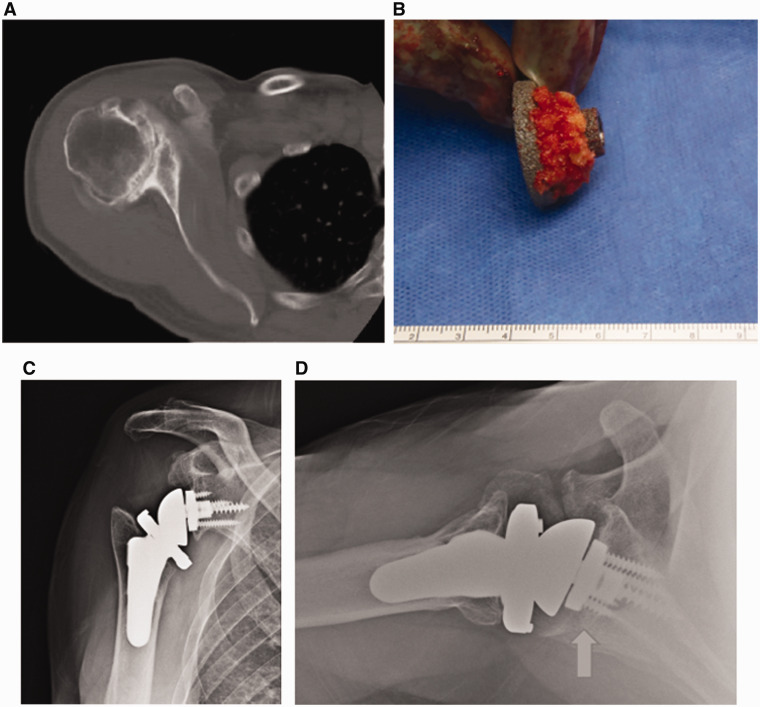

Figure 2.

Impaction grafting can be done by morcellising the humeral head and packing it onto the posterior aspect of the baseplate (B). To optimize fixation, at least 50% of the baseplate should be supported on native bone, with the remainder supported through the bone graft (arrow). Postoperative radiographs demonstrate satisfactory healing of the graft (C and D).

Allograft or autograft can be used to augment posterior glenoid defects, though autograft seems to be preferred in the reported literature. Boileau et al. described a technique of using autologous cancellous humeral autograft termed bony increased-offset RSA (BIO-RSA). 34 The humeral head autograft is placed between the glenoid baseplate and reamed glenoid vault, then fixed with a 25-mm central peg and 4 peripheral screws. By establishing the center of rotation at the bone–prosthesis interface, maximal baseplate fixation and minimal scapular notching are achieved. In effect, the BIO-RSA technique achieves the benefits of a lateralized implant but does so using bone to lateralize the construct rather than the metal glenosphere. 34 Trapezoidal graft can be used for simultaneous correction of version and bone loss in angled BIO-RSA. 35 When applied to 21 patients with type B2 and C deformities, angled BIO-RSA achieved an average of 10.4° of retroversion correction (–21 to –10.6). The authors noted 94% incorporation of the graft by CT and radiographs at 2 years. They also reported a 25% scapular notching rate and had 2 patients with clinically significant baseplate loosening.

Ernstbrunner et al. reported the use of bone graft in primary RSA in 41 patients over a 7-year period. 54 They used autograft in 95% of shoulders and treated posterior glenoid defects in 29% of patients. They reported overall positive results, with a patient satisfaction rate of 93% and improved shoulder scores, pain levels, and range of motion at 2 years. Preoperative predictors of worse outcomes included severe glenoid erosion and increased body mass index. Despite noting relatively high rates of periprosthetic glenoid lucency (18%), incomplete graft incorporation (22%), and scapular notching (30%), none of their patients required revision surgery.

Allograft is less commonly used in primary RSA, with its main applications in revision cases where local autograft options are limited. There are few studies comparing the outcomes of glenoid autograft and allograft use in RSA.44,45 Jones et al. reviewed 44 patients who required structural glenoid bone grafting during RSA, with successful grafting using humeral head autograft (29 patients), iliac crest autograft (1 patient), and femoral head allograft (14 patients). 44 They found no significant difference in incorporation, glenoid component loosening, or infection rates between the 2 groups at 2-year follow-up. They did, however, identify a trend toward increased radiographic graft incorporation of autograft (86%) over allograft (67%). Lopiz et al. reviewed 23 RSA patients who required bone grafting and found no significant difference in autograft (100%) and allograft (92%) incorporation rates at 2 years. 45

Concerns about glenoid bone grafting include graft resorption and incorporation failure, in which the loss of structural support at the graft site could lead to baseplate failure and declining function. Graft resorption can be difficult to identify even on CT scan, with large gaps correctly identified only 46% of the time in a recent cadaver study. 55 In addition, the accentuated deltoid destabilizing force inherent to RSA function could impart stress at the bone–implant interface, resulting in failure of bone grafting. 54 Further research is needed to determine long-term implant survival in the setting of glenoid bone graft, though the early results are promising.

In general, the ease of use, favorable outcomes, and low cost make glenoid bone grafting an attractive option in managing B2 glenoids with RSA. Grafting allows substantial correction of retroversion and bone loss without requiring excessive reaming or modified implants. Specifically, humeral head autograft has been well reported in the literature and seems to be the current preferred technique for dealing with bone loss in RSA patients.

Glenoid Baseplate Augmentation

Metal-augmented total shoulder components were developed to deal with various challenges in shoulder arthroplasty, including posterior glenoid bone loss. Introduced in 2011 for RSA, metal-augmented components help preserve remaining glenoid bone stock and minimize the amount of reaming required.33,40 Several potential negative features of bone grafting are avoided, including limited availability in the revision setting, fixation failure, and postoperative resorption. Augmented baseplates have variable degrees of correction available, allowing the surgeon to tailor the type of implant to the glenoid defect. Correction can be achieved via monoblock or modular components 56 (Figure 3). Augmentation is most common in the posterior and superior quadrants of the baseplate or some combination of the 2.32,40 One drawback of augmented glenoid baseplate use is potential peg or screw perforation through the deficient glenoid in an effort to capture sufficient native bone with the fixation construct, though the impact on glenoid failure rates is undetermined. Higher implant cost, limited implant availability on short notice in some areas, and failure at articulations of modular components are other potential disadvantages of augmented components.

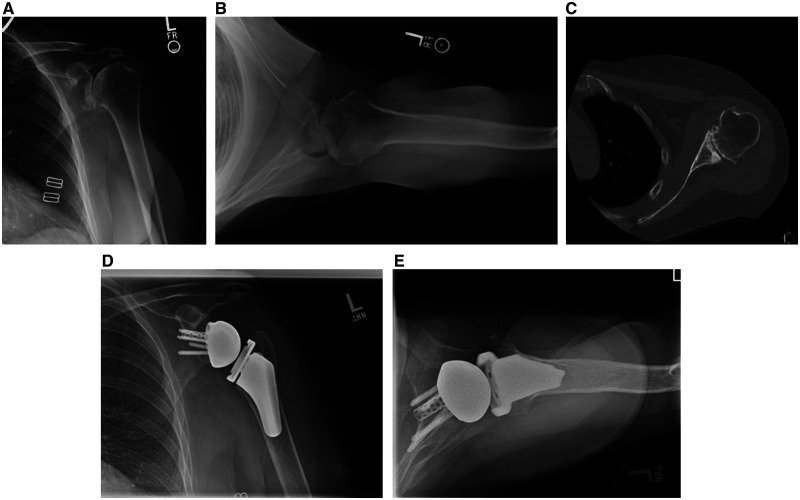

Figure 3.

A patient with a B2 glenoid wear pattern treated with reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. A–C, The glenoid is asymmetrically reamed to prepare for an augmented baseplate . D and E, Postoperative radiographs show satisfactory correction with the augmented component (arrow).

The literature reporting glenoid baseplate augmentation for RSA is evolving, with no long-term outcomes studies to date; however, the results are optimistic. Jones et al. reviewed 80 patients who had RSA with either glenoid bone graft or an augmented baseplate to accommodate a large defect. 33 Their cohort included 24 posteriorly augmented baseplates in patients with an average age of 72 years. At more than 2 years of follow-up, the authors noted similar improvements in pain, motion, and functional scores between the 2 groups. The augmented glenoid group had no significant complications, while the bone graft group had a 14.6% complication rate including 2 patients with glenoid loosening. In addition, there was a lower rate of scapular notching in the augment cohort (10%) than in the bone graft cohort (18.5%). The authors speculated that this could be related to the difficulty in fashioning the bone graft to the asymmetric glenoid with standard implants.

Michael et al. reported the use of augmented glenoid baseplates in 139 RSA patients. 40 They noted an 8% complication rate in the posterior augment cohort but no episodes of glenoid baseplate failure. The complications included an intraoperative tuberosity fracture, 2 traumatic humeral fractures, and a superficial infection treated with oral antibiotics. After experiences with augmented TSA and RSA in glenoid bone deficiency, they favored RSA for the correction of large deformities of more than 20° in elderly patients.

Wright et al. compared the outcomes after posterior and superior augmentation in RSA without reaming or bone grafting. 32 They noted better outcomes and a lower rate of scapular notching (6.3%) in the posteriorly augmented group than in the superiorly augmented group (14.3%). They postulated that the posterior augment prevented posterior contact of the humeral component with the glenoid to minimize notching.

Advances in computing and materials technology have led to the detailed, efficient production of custom baseplates. These implants have been used in TSA for a variety of glenoid bone defects with promising early success.56–59 The customization allows optimization of implant size, screw position, and porous coating. In addition, patient-specific instrumentation can be used to aid in implantation of the custom components. 57 Because of very high implant costs, these components generally are reserved for only the most severely worn glenoids, typically those with erosion past the coracoid base.

As a whole, glenoid augmentation in RSA has shown promise in managing the retroverted, posteriorly deficient B2 glenoid. Despite this, the current literature is sparse and lacks high-powered studies to better delineate its benefits and drawbacks. As with bone grafting, long-term studies assessing implant performance and longevity are needed to determine the optimal treatment strategy.

Conclusion

RSA has several features that make it a useful treatment for patients with a B2 glenoid. Its semiconstrained nature and robust baseplate fixation offer construct stability while preserving motion. Techniques such as eccentric reaming, bone grafting, and baseplate augmentation allow correction of glenoid retroversion and bone loss with promising early results. Further research should focus on improving techniques, determining implant longevity, and measuring long-term outcomes in these patients.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Thomas W. Throckmorton reports IP royalties from Exactech and Zimmer Biomet.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was not required for this review. Patient consent was not required for this review.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Thomas W. Throckmorton https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9346-0919

References

- 1.Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A.Khoury A. Morphologic study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999; 14:756–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bercik MJ, Kruse K, II, Yalizis M.Gauci MO, Chaoui J, Walch G. A modification to the Walch classification of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis using three-dimensional imaging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016; 25:1601–1606. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan K, Knowles NK, Chaoui Jet al. Characterization of the Walch B3 glenoid in primary osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017; 26:909–914. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer DC, Riedo S, Eckers F.Carpeggiani G, Jentzsch T, Gerber C. Small anteroposterior inclination of the acromion is a predictor for posterior glenohumeral erosion (B2 or C). J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019; 28:22–27. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2018.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sears BW, Johnston PS, Ramsey ML.Williams GR. Glenoid bone loss in primary total shoulder arthroplasty: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012; 20:604–613. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-20-09-604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donohue KW, Ricchetti ET, Ho JC.Iannotti JP. The association between rotator cuff muscle fatty infiltration and glenoid morphology in glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018; 100:381–387. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.00232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nyffeler RW, Jost B, Pfirrmann CW.Gerber C. Measurement of glenoid version: conventional radiographs versus computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003; 12:493–496. doi:10.1016/S1058274603001812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulligan RP, Feldman JJ, Bonnaig Net al. Comparison of axillary lateral radiography with computed tomography in the preoperative characterization of glenohumeral wear patterns and the effects of body mass index on quality of imaging. Curr Orthop Pract. 2019; 30:471–476. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rouleau DM, Kidder JF, Pons-Villanueva J.Dynamidis S, Defranco M, Walch G. Glenoid version: how to measure it? Validity of different methods in two-dimensional computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010; 19:1230–1237. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman RJ, Hawthorne KB, Genez BM. The use of computerized tomography in the measurement of glenoid version. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992; 74:1032–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bokor DJ, O'Sullivan MD, Hazan GJ. Variability of measurement of glenoid version on computed tomography scan. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999; 8:595–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scalise JJ, Codsi MJ, Bryan J.Brems JJ, Iannotti JP. The influence of three-dimensional computed tomography images of the shoulder in preoperative planning for total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008; 90:2438–2445. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.01341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scalise JJ, Bryan J, Polster J.Brems JJ, Iannotti JP. Quantitative analysis of glenoid bone loss in osteoarthritis using three-dimensional computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008; 17:328–335 doi:10.1016/j.jse.2007.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verborgt O, De Smedt T, Vanhees M.Clockaerts S, Parizel PM, Van Glabbeek F. Accuracy of placement of the glenoid component in reversed shoulder arthroplasty with and without navigation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011; 20:21–26. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berhouet J, Gulotta LV, Dines DMet al. Preoperative planning for accurate glenoid component positioning in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017; 103:407–413. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2016.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Throckmorton TW, Gulotta LV, Bonnarens FOet al. Patient-specific targeting guides compared with traditional instrumentation for glenoid component placement in shoulder arthroplasty: a multi-surgeon study in 70 arthritic cadaver specimens. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015; 24:965–971. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dallalana RJ, McMahon RA, East B.Geraghty L. Accuracy of patient-specific instrumentation in anatomic and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2016; 10:59–66.doi:10.4103/0973-6042.180717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walch G, Vezeridis PS, Boileau P.Deransart P, Chaoui J. Three-dimensional planning and use of patient-specific guides improve glenoid component position: an in vitro study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015; 24:302–309. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine WN, Djurasovic M, Glasson JM.Pollock RG, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis: results correlated to degree of glenoid wear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997; 6:449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine WN, Fischer CR, Nguyen D.Flatow EL, Ahmad CS, Bigliani LU. Long-term follow-up of shoulder hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012; 94:e164. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilmer BB, Comstock BA, Jette JL.Warme WJ, Jackins SE, Matsen FA. The prognosis for improvement in comfort and function after the ream-and-run arthroplasty for glenohumeral arthritis: an analysis of 176 consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012; 94:e102. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendel MD, Werner BC, Camp CLet al. Management of the biconcave (B2) glenoid in shoulder arthroplasty: technical considerations. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2016; 45:220–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walch G, Moraga C, Young A.Castellanos-Rosas J. Results of anatomic nonconstrained prosthesis in primary osteoarthritis with biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012; 21:1526–1533. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003; 85-A:251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendel MD, Bryan JA, Barsoum WKet al. Comparison of patient-specific instruments with standard surgical instruments in determining glenoid component position: a randomized prospective clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012; 94:2167–2175. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.01209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frankle M, Siegal S, Pupello Det al. The reverse shoulder prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. A minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005; 87:1697–1705. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.02813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denard PJ, Walch G. Current concepts in the surgical management of primary glenohumeral arthritis with a biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013; 22:1589–1598. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein SM, Dunning P, Mulieri P.Pupello D, Downes K, Frankle MA. Effects of acquired glenoid bone defects on surgical technique and clinical outcomes in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010; 92:1144–1154. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mizuno N, Denard PJ, Raiss P.Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis in patients with a biconcave glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013; 95:1297–1304. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donohue KW, Ricchetti ET, Iannotti JP. Surgical management of the biconcave (B2) glenoid. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2016; 9:30–39. doi:10.1007/s12178-016-9315-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu JE, Ricchetti ET, Huffman GR.Iannotti JP, Glaser DL. Addressing glenoid bone deficiency and asymmetric posterior erosion in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013; 22:1298–1308. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright TW, Roche CP, Wright L.Flurin PH, Crosby LA, Zuckerman JD. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty augments for glenoid wear: comparison of posterior augments to superior augments. Bull Hosp Jt Dis (2013). 2015; 73(suppl 1):S124–S128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones RB, Wright TW, Roche CP. Bone grafting the glenoid versus use of augmented glenoid baseplates with reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Bull Hosp Jt Dis (2013). 2015; 73(suppl 1):S129–S135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boileau P, Moineau G, Roussanne Y.O'Shea K. Bony increased-offset reversed shoulder arthroplasty: minimizing scapular impingement while maximizing glenoid fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011; 469:2558–2567. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1775-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boileau P, Morin-Salvo N, Gauci MOet al. Angled BIO-RSA (bony-increased offset-reverse shoulder arthroplasty): a solution for the management of glenoid bone loss and erosion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017; 26:2133–2142. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerber C, Pennington SD, Nyffeler RW. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009; 17:284–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Throckmorton TW. Shoulder and elbow arthroplasty. In: Canale ST, Azar FM, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc., 2017: 570–597. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Favre P, Sussmann PS, Gerber C. The effect of component positioning on intrinsic stability of the reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010; 19:550–556. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilot GJ. Addressing glenoid erosion in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Bull Hosp Jt Dis (2013). 2013; 71(suppl 2):S51–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michael RJ, Schoch BS, King JJ.Wright TW. Managing glenoid bone deficiency-the augment experience in anatomic and reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2018; 47 doi:10.12788/ajo.2018.0014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta A, Thussbas C, Koch M.Seebauer L. Management of glenoid bone defects with reverse shoulder arthroplasty-surgical technique and clinical outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018; 27:853–862. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lorenzetti A, Streit JJ, Cabezas AFet al. Bone graft augmentation for severe glenoid bone loss in primary reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: outcomes and evaluation of host bone contact by 2D-3D image registration. JB JS Open Access. 2017; 2:e0015. doi:10.2106/JBJS.OA.17.00015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neyton L, Boileau P, Nove-Josserand L.Edwards TB, Walch G. Glenoid bone grafting with a reverse design prosthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007; 16:S71–S78. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2006.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones RB, Wright TW, Zuckerman JD. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with structural bone grafting of large glenoid defects. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016; 25:1425–1432. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lopiz Y, Garcia-Fernandez C, Arriaza A.Rizo B, Marcelo H, Marco F. Midterm outcomes of bone grafting in glenoid defects treated with reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017; 26:1581–1588. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McFarland EG, Huri G, Hyun YS.Petersen SA, Srikumaran U. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty without bone-grafting for severe glenoid bone loss in patients with osteoarthritis and intact rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016; 98:1801–1807. doi:10.2106/JBJS.15.01181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clavert P, Millett PJ, Warner JJ. Glenoid resurfacing: what are the limits to asymmetric reaming for posterior erosion? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007; 16:843–848. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2007.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knowles NK, Athwal GS, Keener JD.Ferreira LM. Regional bone density variations in osteoarthritic glenoids: a comparison of symmetric to asymmetric (type B2) erosion patterns. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015; 24:425–432. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frankle MA, Teramoto A, Luo ZP.Levy JC, Pupello D. Glenoid morphology in reverse shoulder arthroplasty: classification and surgical implications. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009; 18:874–885. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahylis JM, Puzzitiello RN, Ho JC.Amini MH, Iannotti JP, Ricchetti ET. Comparison of radiographic and clinical outcomes of revision reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with structural versus nonstructural bone graft. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019; 28:e1–e9. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2018.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scalise JJ, Iannotti JP. Bone grafting severe glenoid defects in revision shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008; 466:139–145. doi:10.1007/s11999-007-0065-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boileau P, Watkinson DJ, Hatzidakis AM.Hovorka I. Grammont reverse prosthesis: design, rationale, and biomechanics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005; 14:147S–161S. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bateman E, Donald SM. Reconstruction of massive uncontained glenoid defects using a combined autograft-allograft construct with reverse shoulder arthroplasty: preliminary results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012; 21:925–934. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ernstbrunner L, Werthel JD, Wagner E.Hatta T, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Glenoid bone grafting in primary reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017; 26:1441–1447. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferreira LM, Knowles NK, Richmond DN.Athwal GS. Effectiveness of CT for the detection of glenoid bone graft resorption following reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015; 101:427–430. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2015.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghoraishian M, Abboud JA, Romeo AA.Williams GR, Namdari S. Augmented glenoid implants in anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty: review of available implants and current literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019; 28:387–395. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2018.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Debeer P, Berghs B, Pouliart N.Van den Bogaert G, Verhaegen F, Nijs S. Treatment of severe glenoid deficiencies in reverse shoulder arthroplasty: the glenius glenoid reconstruction system experience. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019; 28:1601--1608. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2018.11.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chammaa R, Uri O, Lambert S. Primary shoulder arthroplasty using a custom-made hip-inspired implant for the treatment of advanced glenohumeral arthritis in the presence of severe glenoid bone loss. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017; 26:101–107. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gunther SB, Lynch TL. Total shoulder replacement surgery with custom glenoid implants for severe bone deficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012; 21:675–684. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]