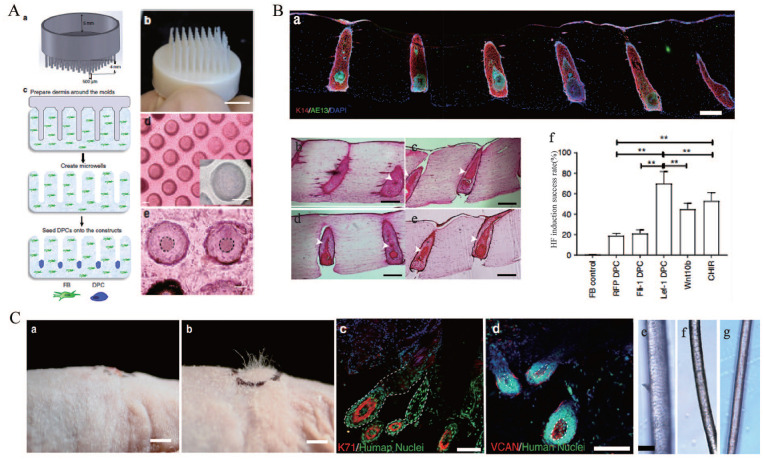

Figure 8.

(A) Patterning of collagen type-1 gel using 3D-printed molds allows for physiological arrangement of cells in the hair follicle. Hair follicle molds were designed (a) and 3D-printed (b), (c) the collagen gel containing dermal fibroblasts could solidify around the HF-like extensions to create an array of microwells in which the DPCs formed spontaneous aggregates, (d) top view of HSCs containing DPCs which settled down into the microwells (lower panel: higher magnification of the microwells), and (e) DPCs formed spontaneous aggregates at the center of the microwells (dashed line circles the aggregates). Scale bars for (d) and (e) are 100 μm. (B) (a) Low magnification image demonstrating expression of AE13 in HSCs generated using Lef-1-transfected DPCs and the high efficiency in HF lineage differentiation, histological H&E staining of the constructs generated by empty vector-transfected DPCs (b), lef-1-transfected DPCs (c), Wnt10b-treated DPCs (d), and CHIR99021-treated DPCs (e) (arrows showing differentiated KC morphology), (f) success rate, defined as the ratio of the HFUs exhibiting hair follicle differentiation to the total number of HFUs, for HSCs with DPCs at different treatment conditions compared to FB control. Scale bars are 300 μm. (C) (a) (as a control), (b) engraftment of high follicle-density HSCs onto immune-deficient nude mice led to hair growth in the grafts after 4–6 weeks (b), (c and d) human-specific nuclear staining (green) indicated that the de novo hair follicles marked with K71 (c) and DPCs marked with VCAN (d) are comprised of human cells. Bright-field microscopy of unpigmented terminal human hair (e), engineered human hair in the grafts (f), and unpigmented human vellus hair (g) showed morphological similarities between human hair and engineered hair. Scale bars for (a, b), (c−d), and (e−g) are 2 mm, 200 μm, and 50 μm respectively.

Source: Adapted with permission from Abaci et al. 193