Abstract

Peptidylarginine deiminases (PAD) enzymes were initially characterized in uteri, but since then little research has examined their function in this tissue. PADs post-translationally convert arginine residues in target proteins to citrulline and are highly expressed in ovine caruncle epithelia and ovine uterine luminal epithelial (OLE)-derived cell line. Progesterone (P4) not only maintains the uterine epithelia but also regulates the expression of endometrial genes that code for proteins that comprise the histotroph and are critical during early pregnancy. Given this, we tested whether P4 stimulates PAD-catalyzed histone citrullination to epigenetically regulate expression of the histotroph gene insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 (IGFBP1) in OLE cells. 100 nM P4 significantly increases IGFBP1 mRNA expression; however, this increase is attenuated by pre-treating OLE cells with 100 nM progesterone receptor antagonist RU486 or 2 µM of a pan-PAD inhibitor. P4 treatment of OLE cells also stimulates citrullination of histone H3 arginine residues 2, 8, and 17 leading to enrichment of the ovine IGFBP1 gene promoter. Since PAD2 nuclear translocation and catalytic activity require calcium, we next investigated whether P4 triggers calcium influx in OLE cells. OLE cells were pre-treated with 10 nM nicardipine, an L-type calcium channel blocker, followed by stimulation with P4. Using fura2-AM imaging, we found that P4 initiates a rapid calcium influx through L-type calcium channels in OLE cells. Furthermore, this influx is necessary for PAD2 nuclear translocation and resulting citrullination of histone H3 arginine residues 2, 8, and 17. Our work suggests that P4 stimulates rapid calcium influx through L-type calcium channels initiating PAD-catalyzed histone citrullination and an increase in IGFBP1 expression.

Introduction

Different species share similar mechanisms for the establishment of pregnancy. Many species’ uterine luminal epithelial cells undergo dramatic reorganization to form glandular epithelia over the course of a female reproductive cycle (Ramathal et al. 2010, Spencer 2014). In sheep, knockout of uterine glands results in pregnancy loss and infertility (Gray et al. 2001, Spencer & Gray 2006, Filant & Spencer 2013). Uterine glandular epithelia secret numerous molecules, collectively known as the histotroph that are critical for the development and survival of the conceptus (Bazer 1975, Kane et al. 1997, Spencer 2014). One such histotroph molecule secreted by uterine epithelia is insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 (IGFBP1). During the secretory phase of the estrous cycle, elevated progesterone (P4) stimulates IGFBP1 gene expression. In several species, including humans and sheep, IGFBP1 is critical for conceptus migration and placentation (Fowler et al. 2000, Simmons et al. 2009).

Some of the original studies investigating the peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD or PADI) enzyme family were conducted using rodent uteri (Takahara et al. 1989, 1992). More recent genome sequencing analysis confirms that PAD expression is higher in uteri than compared to the 50 other tissues examined (Barrett et al. 2009). In the presence of calcium, PADs convert positively charged arginine amino acids in target proteins into neutral citrulline residues, a reaction termed as 'citrullination' or 'deimination'. Early studies discovered that PAD expression in uteri is estrogen-dependent and that levels fluctuate across the estrous cycle (Takahara et al. 1992). In fact, one of the first cDNAs of a PAD enzyme was cloned from rodent uteri; however, since these groundbreaking studies, little work has investigated the functional role of PADs in this tissue (Takahara et al. 1989, 1992, Terakawa et al. 1991). Similar to rodent uteri, PADs are highly expressed in luminal and glandular epithelial cells in caruncle tissue from sheep during early pregnancy. We also found that PADs citrullinate arginine residues 2, 8, and 17 on the histone H3 tail to regulate basal expression of IGFBP1 in an ovine luminal epithelial (OLE) cell line (Young et al. 2017). Given that IGFBP1 expression is critical to maintain early pregnancy and is stimulated by P4, we investigated whether P4 induces histone citrullination to regulate IGFBP1 expression.

Calcium influx and its effect on intracellular signaling are critical for adhesion, decidualization, and placentation (Lee et al. 2009, Kumar et al. 2015, De Clercq & Vriens 2018). It is also established that PAD enzymatic activity and nuclear translocation are calcium-dependent (Arita et al. 2004, Zheng et al. 2019); however, the mechanisms underlying P4-induced calcium influx and the link to PAD function are not clear. With classical steroid receptor signaling, P4 diffuses through the plasma membrane and binds to the nuclear progesterone receptor (nPR). The complex then translocates to the nucleus and binds progesterone response elements (PREs) in promoters to activate gene expression. Currently, there is limited evidence in the literature to suggest that the nPR is directly involved in mediating a rapid calcium influx into cells. Membrane progesterone receptors (mPRs) further complicate our understanding of a P4-induced calcium influx mechanism in uterine epithelial cells. Ovine mPRs bind P4 with high affinity and can modulate intracellular calcium levels (Ashley et al. 2006, 2009, Viero et al. 2006, Dressing et al. 2011). Additionally, unique P4-mediated mechanisms, independent of nPRs and mPRs, have also been discovered that trigger rapid calcium influx such as in human sperm cells and in Xenopus laevis oocytes (Wasserman et al. 1980, Thomas & Meizel 1989). Currently, how P4 induces calcium influx in uterine luminal epithelial cells is unclear.

Herein, our studies show that P4 stimulates citrullination of histone H3 arginine residues 2, 8, and 17 and results in a significant increase in IGFBP1 mRNA in OLE cells. The increase in IGFBP1 mRNA is inhibited by pretreating OLE cells with P4 antagonist RU486 and the pan-PAD inhibitor, BB-Cl-amidine (BB-ClA). We also demonstrate that citrullinated histones are enriched on the ovine IGFBP1 gene promoter following P4 treatment compared to vehicle-treated controls. Interestingly, our results show that P4 initiates a rapid calcium influx through an L-type calcium channel, which is important for PAD2 nuclear translocation and ultimately histone citrullination in OLE cells. Collectively, our work suggests that P4 stimulates rapid calcium influx through L-type calcium channels initiating PAD-catalyzed histone citrullination and increased IGFBP1 expression.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and materials

OLE cells, a generous gift from Dr Greg Johnson, were maintained in high glucose DMEM containing 2 mM glutamine, 100 U penicillin/mL, 100 μg streptomycin/mL and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) as previously described (Young et al. 2017). For all P4 (MiliporeSigma) treatments, OLE cells were incubated overnight in phenol red-free DMEM (Hyclone) with 2.5% FBS (Corning). All cells were grown in 5% CO2 at 37°C in a humidified environment. OLE cells were treated with PAD inhibitor, biphenyl-benzimidazole-Cl-amidine (BB-ClA) which was synthesized and generously provided by Dr Paul R Thompson as previously described (Knight et al. 2015).

Ewe uterine epithelial cells

Primary ewe uterine epithelial cells were collected from dissected uterine horns as previously described (Johnson et al. 1999). Briefly, each uterine horn was washed with PBS and filled with 20 mL of Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) with 2.5 mg/mL pancreatin and 4.8 mg/mL of dispase II (MiliporeSigma). Uterine horns were incubated at 37°C for 1 h and massaged to remove epithelial cell sheets. Cells were then dispersed, plated, and maintained in high glucose DMEM containing 2 mM glutamine, 100 U penicillin/mL, 100 μg streptomycin/mL and 10% FBS (HyClone). All cells were maintained in 5% CO2 at 37°C in a humidified environment. Rambouillet ewes (Ovis aries) were maintained with access to food and water ad libitum. Euthanasia and tissue harvest were performed in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the Report of the AVMA on Euthanasia. The study was approved by the University of Wyoming Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #20190618BC00377-01).

Immunocytochemistry (ICC)

Primary ewe uterine epithelial and OLE cells were plated in MatTek Life Sciences 35 mm glass-bottom dishes (Ashland, MA, USA). After being fixed and permeabilized, cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C (anti-H3Cit 2,8,17 1:150, Abcam ab5103), (anti-PAD2 1:150, Proteintech 12110-1-AP, Rosemont, IL, USA), (anti-PAD4 1:100, MiliporeSigma, P4749). Duplicate dishes were incubated with an equal mass of non-specific rabbit IgG as a negative control. The following morning dishes were washed 3× in PBS before incubation with a fluorophor-conjugated secondary antibody. Cells were imaged using a Zeiss 710 or 980 LSM confocal microscope under a 40× or 63× objective, respectively.

Western blotting

OLE cells were treated with vehicle or 100 nM P4 for 30 or 60 min. For nicardipine studies, OLE cells were pre-treated with 10 nM nicardipine (MiliporeSigma) for 30 min followed by addition of vehicle or 100 nM P4 for an additional 30 (PAD2) or 60 min (H3Cit 2,8,17). OLE nuclear fractionation and histone purification were performed as previously described (Bezy et al. 2007, Shechter et al. 2007, Cherrington et al. 2012, Young et al. 2017). Protein concentration of OLE lysates and purified histones was measured by Pierce 660 nm protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) prior to gel loading to ensure equal protein loading. Sample buffer consisting of 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 60% glycerol, 30 mM DTT, 6% SDS was added to samples to yield a final concentration of 1× and then boiled at 95°C for 5 min. The samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE using 12 or 15% gels (acrylamide:bis-acrylamide ratio of 29:1) and subsequently transferred to Immobilon PVDF membranes (MilliporeSigma). Membranes were blocked in 1× casein (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA) diluted in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies were incubated 1:1000 overnight at 4°C: H3Cit 2,8,17, PAD2, and total histone H3 (Abcam, ab1791). The following morning, membranes were washed in TBS-T, followed by a 2-h incubation at room temperature with 1:10,000 goat anti-rabbit HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs) secondary antibody. All blots were washed for 50 min (5 × 10 min) with TBS-T after secondary antibody incubation and then visualized using SuperSignal West Pico and Femto chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Quantitative densitometry analysis was conducted with Bio-Rad Image Lab software (Hercules, CA, USA). The experiments were repeated at least three independent times and values are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. Means were separated by one-way ANOVA using SNK and * indicates significantly different means P < 0.05.

qPCR

Total RNA was purified from OLE cells following 2 h treatment with vehicle or 1, 10, and 100 nM P4. For PAD inhibitor studies, OLE cells were pre-treated with 100 nM RU486 (MilliporeSigma) for 1 h or 2 µM BB-ClA for 3 h then stimulated with 100 nM P4 for an additional 2 h. Primary ewe uterine epithelial cells were also treated with 100 nM P4 for 2 h. RNA was purified according to the Omega Bio-Tek Total RNA Kit protocol (Omega Bio-Tek, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA). One microgram of resulting RNA was reverse transcribed using iScript RT Supermix for RT-qPCR (Bio-Rad). cDNA was subjected to real-time PCR analysis with SYBR Green (Bio-Rad) using intron spanning primers: IGFBP1 FWD 5′-CAGCAAACAGTGTGAGACTTCG-3′, REV 5′-TCCCACTCCAAGGGTAGACA-3′; GAPDH FWD 5′-CGTTCTCTGCCTTGACTGTG-3′, REV 5′-TGACCCCTTCATTGACCTTC-3′. Data were analyzed using the ΔΔct method in which ct values of target genes were adjusted to the corresponding ct value of the reference gene (GAPDH). The experiment was repeated at least three independent times and values are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. Means were separated using SNK or a one-tailed paired Student’s t-test and * indicates significantly different means (*P < 0.05).

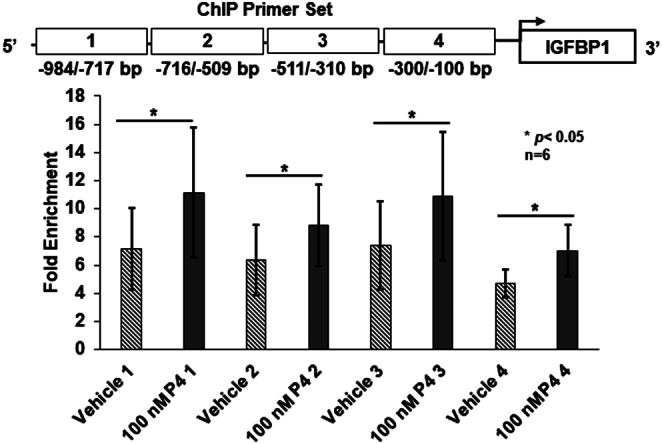

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Following overnight serum starvation, OLE cells were treated with either vehicle or 100 nM P4 for 1 h then cross-linked at room temperature (RT) in 1% formaldehyde for 10 min. ChIP was performed with a SimpleChip® Plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (Cell Signaling Technologies) and optimized for OLE cells. The chromatin was immunoprecipitated using anti-H3Cit 2, 8, 17 (Abcam), while non-specific IgG and total histone H3 are controls. Enriched DNA was then subjected to qPCR using primers that scan approximately 1000 bps upstream of the transcriptional start site of the ovine IGFBP1 gene: 1 (-984/-717 bp) FWD 5′-GAGGCTGAAAGACAGAGGAAAC-3′, REV 5′-CCCAGTTAACAGAGCTTCCA-3′; 2 (−716/−509 bp) FWD 5′-CTTTGGGGGCTATGGTGAGAC-3′, REV 5′-AAGAGGAAGGAGCGCTTTGAA-3′; 3 (−511/−310 bp) FWD 5′-CTTCCCGGGCCTTGATTTC-3′, REV 5′-GTTCAGACCTGGAGCCAAAGT-3′; 4 (−300/−100 bp) FWD 5′-AGGACAAACACAGTCTGAAACG-3′, REV 5′-TGGCCGATGCTCGCTGA-3′. Levels of citrullinated histones associated with the ovine IGFBP1 gene promoter were normalized to IgG using the fold enrichment method and are shown as vehicle compared to P4-treated cells for each of the four primer sets. The ChIP experiments were performed si independent times. Samples were analyzed using a one-tailed paired Student’s t-test in which vehicle was compared to P4-treated cells and * indicates significantly different means (*P < 0.05).

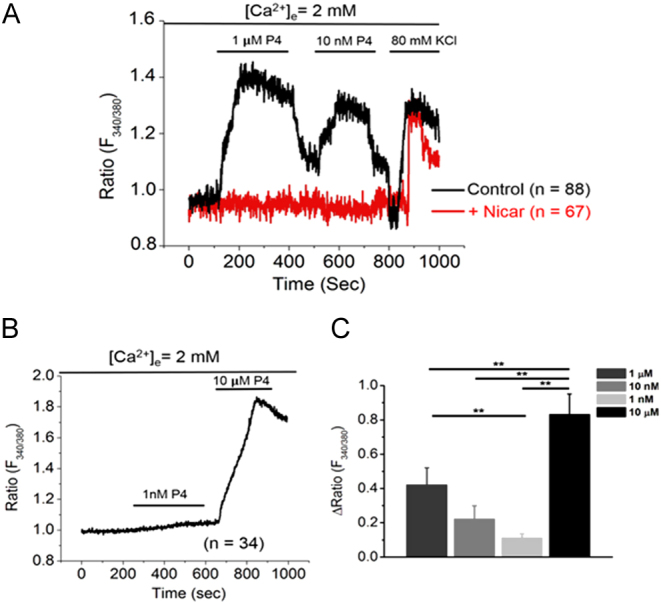

Intracellular Ca2+ imaging

OLE cells were grown on 25 mm circular coverslips and incubated with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fura-2AM (2 μM) for 1 h at RT in normal extracellular solution (NES) (137 NaCl mM, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES and pH adjusted to 7.4 by NaOH). Coverslips were washed and incubated with NES for 30 min at RT in the dark. The coverslips were placed in a stainless-steel holder (bath volume ∼0.8 mL) and imaged using a Leica DMI300 B inverted microscope coupled to a TILL Polychrome V digital imaging system (Toptica Photonics, Farmington, NY, USA). Cells were treated with flow-through of 1 µM P4 for 100–400 seconds, 10 nM for 500–700 s, and 80 mM KCl at 800 s. In parallel, a second coverslip of cells was pretreated with 10 nM nicardipine for 30 min followed by the same treatment paradigm described previously. Results present the ratio (R/R0) of fluorescence intensities at the excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm. Ca2+ imaging data were analyzed using Origin 2020 Software (Origin Lab, Northampton, MA, USA), and data for all figures are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Student’s t-test and ** represents statistical significance (**P < 0.01).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated independently at least three times and resulting values are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was determined using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software). Means were separated using SNK or Student’s t-test and * indicate significantly different means (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01).

Results

Progesterone stimulates IGFBP1 mRNA expression in OLE and ovine primary uterine epithelial cells

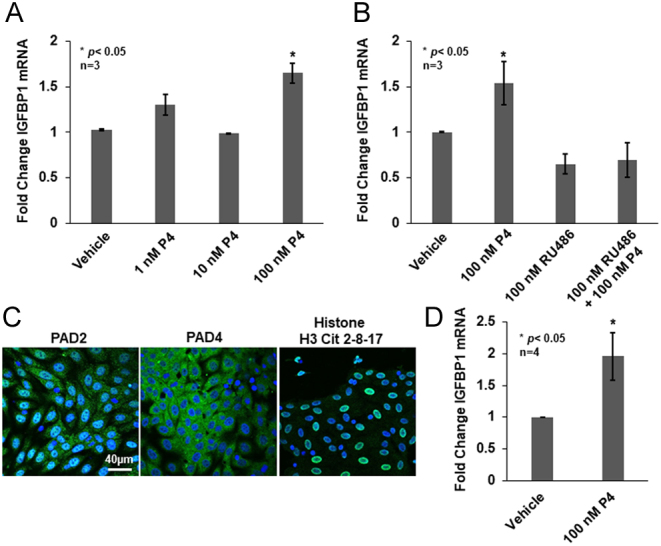

We previously found that PADs regulate basal IGFBP1 mRNA expression in OLE cells (Young et al. 2017). Since P4 stimulates IGFBP1 expression in other models, we first tested if this also occurs in OLE cells. OLE cells were serum-starved overnight then treated with vehicle or 1, 10, and 100 nM P4 for 2 h. RNA was purified, reverse transcribed, and the resulting cDNA was analyzed by qPCR using primers specific for IGFBP1 with GAPDH serving as an endogenous control. Our results show a significant 1.6-fold increase in IGFBP1 mRNA following 2 h of 100 nM P4 treatment compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 1A). Following the same paradigm, we next investigated whether the P4-induced increase in IGFBP1 mRNA expression is mediated by a PR. OLE cells were pre-treated with 100 nM RU486 for 1 h then stimulated with 100 nM P4 for an additional 2 h. While P4 alone stimulates an increase in expression, pre-treatment with a RU486 significantly reduces IGFBP1 mRNA levels indicating a PR-mediated mechanism (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Progesterone stimulates IGFBP1 mRNA expression in OLE and ovine uterine primary epithelial cells. (A) OLE cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or with 1, 10, and 100 nM P4 for 2 h. Total RNA was purified, reverse transcribed, and the resulting cDNA examined by qPCR with intron spanning primers for IGFBP1 and GAPDH as the reference gene control. All values are expressed as means ± s.e.m. Means were separated using Student–Newman–Keuls (SNK) (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (B) OLE cells were treated with vehicle (Etoh) or 100 nM RU486 for 1 h followed by 100 nM P4 for an additional 2 h. Total RNA was purified, reverse transcribed, and the resulting cDNA examined by qPCR with intron spanning primers for IGFBP1 and GAPDH as the reference gene control. All values are expressed as means ± s.e.m. Means were separated using SNK (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (C) Ewe primary uterine epithelial cells were grown on glass bottom dishes overnight then fixed, permeabilized, and examined by immunocytochemistry using anti-PAD2, anti-PAD4, and anti-histone H3Cit 2, 8, 17 antibodies (green) and stained with DAPI (blue). Cells were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope using a 40× objective and scale bar is 40 µm. (D) Ewe primary uterine epithelial cells were grown overnight then the following morning treated with vehicle or 100 nM P4 for 2 h. Total RNA was purified from primary cells and reverse transcribed to cDNA. The cDNA was examined by qPCR with intron spanning primers for IGFBP1 and GAPDH as the reference gene control. All values are expressed as means ± s.e.m. Means were separated using a one-tailed paired t-test with * indicating significant differences (n = 4, *P < 0.05).

In OLE cells, 100 nM P4 stimulates a significant increase in expression of IGFBP1, thus, we next validated this dose using ewe primary uterine luminal epithelial cells (Johnson et al. 1999). First, we confirmed that PAD2, PAD4, and citrullinated histones are present in dispersed ewe primary uterine luminal epithelial cells. Cells were grown overnight, fixed, and examined by immunocytochemistry (ICC) using anti-PAD2, anti-PAD4, and anti-histone H3Cit 2,8,17 antibodies. Cells were imaged using confocal laser scanning microscopy with a 40× objective. Both PAD2 and PAD4 staining is observed in the primary cells; however, PAD2 appears to have stronger nuclear localization compared to PAD4 (Fig. 1C). Imaging studies also detected strong histone H3Cit 2,8,17 staining in the nuclei of ewe primary uterine luminal epithelial cells. This PAD expression and citrullinated histone profile were also observed in our previous studies examining the OLE cell line and ewe caruncle histological tissue sections (Young et al. 2017). Lastly, we treated ewe primary uterine luminal epithelial cells with 100 nM P4 for 2 h and then quantified IGFBP1 mRNA expression. Our results show a significant two-fold increase in IGFBP1 mRNA following 100 nM P4 treatment recapitulating our OLE studies suggesting that this dose elicits a similar response in ewe primary uterine luminal epithelial cells (Fig. 1D).

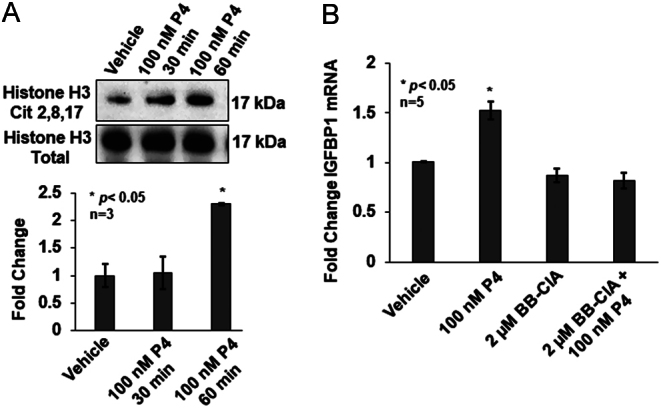

Progesterone stimulates PAD-catalyzed citrullination to regulate IGFBP1 mRNA expression

We next investigated whether the P4-induced increase in IGFBP1 mRNA expression is mediated by PAD-catalyzed citrullination. To test this possibility, OLE cells were treated with vehicle or 100 nM P4 for 30 and 60 min. Following treatment, histones were isolated and equal concentrations were examined by Western blot. Membranes were probed with an anti-histone H3Cit 2,8,17 antibody and total histone H3 as the loading control. A representative Western blot illustrates that 60 min of 100 nM P4 treatment increases histone citrullination as compared to 60 min vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 2A). Quantification of multiple blots shows that P4 significantly increases histone H3 citrullination of arginine residues 2, 8, and 17 by greater than two-fold following 60 min of treatment as compared to vehicle alone (n = 3, *P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that 100 nM P4 rapidly stimulates PAD-catalyzed histone citrullination in OLE cells.

Figure 2.

Progesterone stimulates PAD-catalyzed citrullination to regulate IGFBP1 mRNA expression. (A) OLE cells were stimulated with vehicle (DMSO) or 100 nM progesterone for 30 or 60 min. After cell lysis, histones were purified and equal amounts examined by Western blot. Membranes were probed with an anti-histone H3Cit 2, 8, 17 antibody or anti-total histone H3 as a loading control. The top panel shows a representative Western blot, while the bottom graph represents the quantification of multiple Western blots using BioRad Image Lab 4.0. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. and separated using SNK (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (B) OLE cells were pretreated with vehicle (DMSO) or 2 μM BB-ClA for 3 h followed by stimulation with 100 nM P4 for 2 h. Total RNA was purified, reverse transcribed, and then cDNA was examined by qPCR with intron spanning primers for IGFBP1 and GAPDH as the reference gene control. All values are expressed as means ± s.e.m. Means were separated using SNK (n = 5, *P < 0.05).

These findings led us to hypothesize that P4 induces PAD-catalyzed citrullination to stimulate IGFBP1 gene expression. To test this, we examined the expression of IGFBP1 mRNA in OLE cells following pre-treatment with DMSO or 2 μM BB-ClA for 3 h as previously described (Young et al. 2017) then treated for an additional 2 h with 100 nM P4 or vehicle. After treatment, RNA was purified, reverse transcribed, and resulting cDNA was analyzed by qPCR using primers specific for IGFBP1 with GAPDH serving as an endogenous control. Our results show a significant 1.5-fold increase in IGFBP1 mRNA following 2 h of P4 treatment; however, there is no P4-induced increase in IGFBP1 mRNA expression when cells are pre-treated with BB-ClA (n = 5, *P < 0.05) (Fig. 2B). This result suggests that P4 stimulates PAD-catalyzed citrullination to regulate IGFBP1 mRNA expression in OLE cells.

Progesterone increases citrullinated histone H3 residues 2, 8, and 17 associated with the ovine IGFBP1 gene promoter

Since PAD inhibition blocks P4-induced IGFBP1 mRNA expression, we investigated if citrullinated histones are directly associated with the ovine IGFBP1 gene promoter. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed using OLE cells that were treated with either vehicle or 100 nM P4 for 60 min. Post-treatment, OLE chromatin was immunoprecipitated with the anti-histone H3Cit 2,8,17 antibody and analyzed by qPCR using four sets of primers that scan approximately 200 bps. The four primer sets cover approximately 1000 bp upstream of the ovine IGFBP1 gene transcriptional start site. Our ChIP results show that P4 treatment significantly increases enrichment of citrullinated histone H3 residues directly associated with the IGFBP1 gene promoter in all primer sets as compared to vehicle-treated cells (n = 6, *P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). These results are the first to find that P4 significantly increases histone citrullination at the ovine IGFBP1 gene promoter.

Figure 3.

Progesterone increases citrullinated histone H3 residues 2, 8, and 17 associated with the ovine IGFBP1 gene promoter. OLE cells were treated with vehicle or 100 nM P4 for 60 min. Cross-linked histone-DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated with an anti-histone H3Cit 2,8,17 antibody, anti-histone H3 antibody (positive control), or nonspecific IgG (negative control). After reversing cross-links, DNA was purified and examined by qPCR with primers that scanned the proximal ovine IGFBP1 gene promoter. Results were analyzed using the fold enrichment method, all values are means ± s.e.m., and means were separated using a one-tailed paired t-test (n = 6, *P < 0.05).

Progesterone rapidly stimulates an increase in intracellular calcium via L-type calcium channels in OLE cells

Our previous work in the gonadotropin-derived LβT2 cell line discovered that activation of L-type calcium channels is necessary for PAD2 nuclear translocation (Khan et al. 2016). This led us to hypothesize that P4 induces a rapid calcium influx via L-type calcium channels in OLE cells. OLE cells were loaded with 2 μM fluorescent calcium indicator Fura-2AM for 1 h at room temperature, then mounted in a flow cell with normal extracellular saline (NES) buffer. Cells were treated by flow-through of 1 µM P4 from 100 to 400 s, 10 nM P4 from 500 to 700 s, and 80 mM KCl at 800 s (n = 88 cells quantified) (Fig. 4A, black trace). Between each treatment, cells were washed for 100 s with NES to flush the previous treatment. KCl was given as a positive control as it induces massive calcium influx in live cells. In parallel, a second coverslip of cells was pretreated with 10 nM of the L-type calcium channel blocker nicardipine for 30 min followed by the same treatments described previously (n = 67 cells quantified) (Fig. 4A, red trace) (Kasai et al. 1995). An additional coverslip of cells was treated with 1 nM P4 for 100–400 s and then with 1 µM P4 for 400–700 s (n = 34 cells quantified) (Fig. 4B). Our results show a P4 dose-dependent increase in the 340/380 fluorescence ratio in OLE cells indicating a rapid calcium influx following treatment (Fig. 4C). Moreover, when the OLE cells are pretreated with nicardipine, the 340/380 fluorescence ratio does not increase following P4 treatment, indicating that extracellular calcium influx occurs via L-type calcium channels.

Figure 4.

Progesterone stimulates a rapid increase in intracellular calcium via L-type calcium channels in OLE cells. OLE cells were plated on 25 mm circular coverslips and incubated overnight. The following morning, cells were incubated with 2 μM Fura-2AM for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then mounted in a flow cell with normal extracellular saline (NES) buffer. (A) Cells were treated with flow through of 1 µM P4 for 100–400 s, 10 nM P4 for 500–700 s, and with 80 mM KCl at 800 s with NES washes in between each treatment (n = 88 cells quantified). In parallel, another coverslip of cells was pretreated with 10 nM nicardipine for 30 min and then subjected to the same P4 treatment protocol (n = 67 cells quantified). (B) Cells were treated with 1 nM P4 for 100–400 s and with 10 µM P4 for 600–800 s followed by a wash at 1000 s (n = 34 cells quantified). (C) The bar graph represents the analysis of the mean change in 340/380 ratio for all P4 treatments: 1 µM (n = 88), 10 nM (n = 88), 1 nM (n = 34), 10 µM (n = 34). Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Student’s t-test. Data are expressed as mean + s.e.m. and ** represents statistical significance (P < 0.01). Analyzed data were plotted using Microcal Origin 2020 software.

PAD2 nuclear translocation and histone citrullination are dependent on progesterone-induced activation of L-type calcium channels in OLE cells

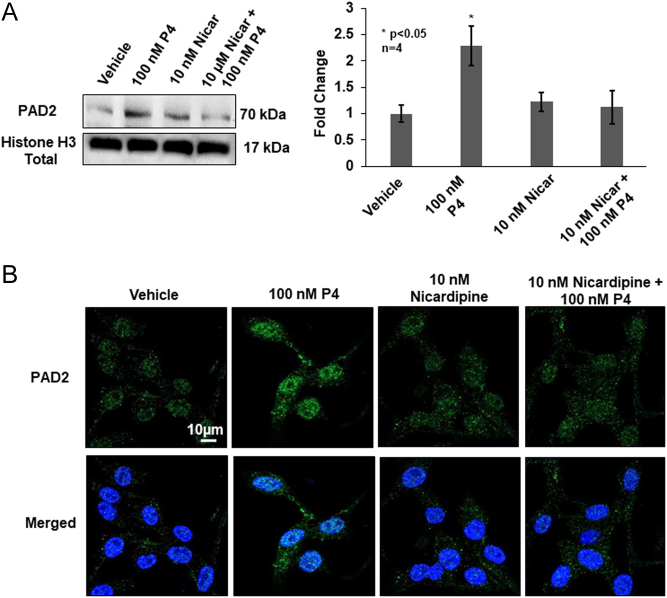

PAD2 nuclear translocation and catalytic activity are both calcium-dependent (Arita et al. 2004, Mondal & Thompson 2019, Zheng et al. 2019). Thus, we hypothesized that P4-induced calcium influx through L-type calcium channels is necessary for PAD2 nuclear translocation and subsequent histone citrullination. To test this hypothesis, OLE cells were pretreated with DMSO or 10 nM nicardipine for 30 min followed by stimulation with 100 nM P4 or vehicle for an additional 30 min. Following treatment, chromatin-associated proteins were isolated and equal concentrations were examined by Western blot using an anti-PAD2 antibody. A representative Western blot shows that 30 min of P4 treatment increases PAD2 nuclear translocation as compared to vehicle-treated controls; however, pretreatment with nicardipine attenuates PAD2 nuclear localization (Fig. 5A). Quantification of multiple blots (n = 4, *P < 0.05) supports that P4-induced PAD2 nuclear translocation is significantly blunted by blocking calcium influx through L-type calcium channels in OLE cells. These results were corroborated by performing immunocytochemistry on OLE cells treated as described previously. 100 nM P4 treatment of OLE cells for 30 min results in an increase in PAD2 staining in the nucleus, but this is blunted by the pretreatment with 10 nM nicardipine (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Progesterone stimulates calcium influx via L-type calcium channels to mediate PAD2 nuclear translocation. (A) OLE cells were pre-treated with vehicle (DMSO) or 10 nM nicardipine for 30 min then stimulated with vehicle (DMSO) or 100 nM P4 for an additional 30 min. Following cell lysis, chromatin-associated nuclear proteins were isolated and equal amounts were examined by Western blot. Membranes were probed with an anti-PAD2 antibody or anti-total histone H3 as a loading control. The left panel shows a representative Western blot, while the graph on the right illustrates the quantification of multiple Western blots using BioRad Image Lab 4.0. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. and separated using SNK (n = 4, *P < 0.05). (B) OLE cells were grown on glass bottom dishes overnight then fixed, permeabilized, and examined by immunocytochemistry using an anti-PAD2 antibody (green) and stained with DAPI (blue). Cells were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 980 confocal microscope using a 63× objective and scale bar is 10 µm.

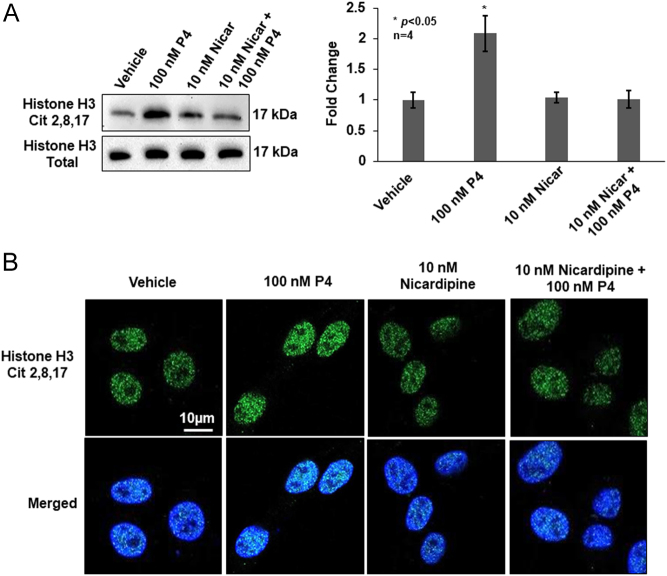

Once PAD2 translocates to the nucleus, a corresponding increase in histone citrullination should occur. We tested this idea by pretreating OLE cells for 30 min with 10 nM nicardipine then stimulating them with 100 nM P4 for 60 min when histone H3Cit 2,8,17 levels are maximal (Fig. 2A). After purification, equal concentrations of histones were examined by Western blot, and membranes were probed with the anti-histone H3Cit 2,8,17 antibody and total histone H3 antibody as a loading control. A representative Western blot indicates that 60 min of P4 treatment increases histone citrullination as compared to vehicle-treated controls; however, pre-treatment with nicardipine attenuates this increase (Fig. 6B). Quantification of multiple blots (n = 4, *P < 0.05) indicates that P4-induced histone citrullination is significantly blunted by blocking calcium influx through L-type calcium channels. This finding was corroborated by performing immunocytochemistry on OLE cells treated as described previously. Treatment of OLE cells for 60 min with 100 nM P4 results in an increase in H3Cit 2,8,17 staining in the nucleus, but this is blunted by the pretreatment with 10 nM nicardipine (Fig. 6B). Taken together, our results suggest that P4 stimulates a rapid calcium influx through L-type calcium channels that are important for PAD2 nuclear translocation and histone citrullination.

Figure 6.

Progesterone stimulates calcium influx via L-type calcium channels resulting in increased histone H3 citrullination. (A) OLE cells were pretreated with vehicle (DMSO) or 10 nM nicardipine for 30 min then stimulated with vehicle (DMSO) or 100 nM P4 for an additional 60 min. Following cell lysis, chromatin-associated nuclear proteins were isolated and equal amounts were examined by Western blot. Membranes were probed with an anti-Histone H3Cit 2,8,17 antibody or anti-total histone H3 as a loading control. The top left panel shows a representative Western blot, while the graph to the right illustrates the quantification of multiple Western blots using BioRad Image Lab 4.0. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. and separated using SNK (n = 4, *P < 0.05). (B) OLE cells were grown on glass bottom dishes overnight then fixed, permeabilized, and examined by immunocytochemistry using an anti-Histone H3Cit 2,8,17 antibody (green) and stained with DAPI (blue). Cells were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 980 confocal microscope using a 63X objective and scale bar is 10 µm.

Discussion

In women, pregnancy loss or miscarriage occurs in approximately 20% of all pregnancies with the majority occurring before the 12th week of gestation (Dante et al. 2013). Embryo loss in early pregnancy is also an important consideration in agricultural animals (Diskin et al. 2006, Dixon et al. 2007, Kwak-Kim et al. 2010). The uterine milk or histotroph, which is comprised of numerous molecules secreted by uterine glandular epithelial cells, is essential to nourish the early embryo, facilitate placental development, and for blastocyst survival and growth (Spencer et al. 2004). In particular, IGFBP1 facilitates migration and attachment of the trophectoderm in multiple species (Gleeson et al. 2001, Brooks et al. 2014). Our previous work shows that basal IGFBP1 expression in OLE cells is regulated by histone citrullination (Young et al. 2017). Since P4 is known to stimulate IGFBP1 expression, herein we investigated the mechanism by which P4 activates PAD-catalyzed histone citrullination to regulate IGFBP1 expression.

For these studies, we used OLE cells that were originally isolated from uterine epithelium collected on the 5th day of the ewe estrous cycle (Johnson et al. 1999). Our previous studies found that OLE cells express PAD enzymes and contain citrullinated histones (Young et al. 2017). We chose to examine mRNA expression after 2 h of P4 treatment since IGFBP1 can be rapidly and dynamically regulated (Tazuke et al. 1998, Fowler et al. 2000). IGFBP1 mRNA expression in OLE cells was first examined following treatment with increasing concentrations of P4. 100 nM P4 stimulates a significant increase in IGFBP1 mRNA expression in OLE cells and in ewe primary uterine epithelial cells. Although this is higher than found in ewe serum, this concentration has been used to treat OLE cells and in other model systems (Banu et al. 2010, Goddard et al. 2014, Kavlashvili et al. 2016).

Work from our lab found that gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) induces calcium influx through L-type calcium channels resulting in PAD2 nuclear translocation in gonadotropin-derived LβT2 cells (Edwards et al. 2016, Khan et al. 2016). PAD2 does not contain a classical nuclear localization sequence, but Zheng et al. found that PAD2 nuclear translocation is a calcium-dependent process (Zheng et al. 2019). The binding of calcium to PAD2 weakens its interaction with annexin 5, a phospholipid-binding protein, allowing increased association with RanGDP which facilitates nuclear translocation (Zheng et al. 2019). Based on these findings, we tested whether P4 stimulates a rapid calcium influx via activation of L-type calcium channels in OLE cells thereby stimulating PAD2 nuclear translocation. Our calcium imaging data clearly shows that P4 stimulates rapid calcium influx via L-type calcium channels. However, we cannot rule out the contribution of intracellular calcium mobilization on PAD2 translocation, a possibility that will require further investigation. Collectively, our results suggest that P4 initiates a rapid calcium influx in OLE cells, which causes PAD2 nuclear translocation which ultimately results in increased histone citrullination.

Once in the OLE nucleus, PADs citrullinated histone H3 arginine residues 2, 8, and 17 with maximal levels occurring after 60 min of P4 treatment. PADs hydrolyze the positive guanidinium group of arginine residues on histones converting arginine to neutral citrulline, which modifies chromatin structure to alter gene expression (Hagiwara et al. 2002, Wang et al. 2009, Tanikawa et al. 2012). Pretreating OLE cells with 2 µM BB-ClA, which binds covalently to the PAD enzyme active site, blunts the P4-induced increase in IGFBP1 mRNA (Horibata et al. 2015, Knight et al. 2015). Although P4 stimulates the expression of critical endometrial genes that code for proteins that comprise the histotroph such as IGFBP1, the underlying epigenetic mechanisms remain poorly characterized (Spencer et al. 2016). Our ChIP results indicate that the proximal promoter region of the ovine IGFBP1 gene is enriched with citrullinated histones following P4 treatment compared to vehicle-treated controls. In addition to histone citrullination regulating expression, Tamura et al. found an increase in acetylation of histone H3 lysine 27 associated with the IGFBP1 gene promoter during decidualization (Tamura et al. 2018). In women, the IGFBP1 gene promoter contains a progesterone response element (PRE) (Gao et al. 1999); yet, to the best of our knowledge, the ovine IGFBP1 gene does not contain a PRE. Sequence analysis of the ovine IGFBP1 gene promoter region shows putative binding sites for the forkhead winged-helix (FOX) family of transcription factors. In human endometrial cells, FOXO1A interacts with the nPR to induce expression of the IGFBP1 gene (Kim et al. 2005). Our results suggest that nPRs may be interacting with a number of transcription factors such as FOXO1A that bind at multiple sites across the proximal ovine IGFBP1 gene promoter. Clearly, additional studies are necessary to determine how the ovine IGFBP1 gene is regulated by P4 in the absence of a PRE.

In uterine tissue, L-type calcium channels are present in the myometrium and mediate the calcium influx required for parturition (Collins et al. 2000). In human endometrial cells, channel blockers reduce intracellular calcium levels resulting in changes in the expression of decidualization and glandular maturation genes. Specifically, blocking calcium influx in human endometrial cells results in a decrease in IGFBP1 levels supporting the idea that a calcium-dependent mechanism regulates IGFBP1 expression (Kusama et al. 2015). Yet, our results pose an interesting mechanistic question regarding how P4 activates L-type calcium channels in OLE cells irrespective of P4’s role in stimulating IGFBP1 gene expression. In the gonadotropin-derived αT3-1 cell line, GnRH treatment, acting through the GnRH receptor (GnRHR), requires protein kinase C and the cytoskeletal filament actin to activate L-type calcium channels. This activation generates localized subplasma membrane sites of calcium influx, termed 'calcium sparklets' (Dang et al. 2014). A similar high calcium microdomain localized close to intracellular ion channels has been hypothesized to mediate the calcium environment necessary for full PAD catalytic activation. It is currently unclear if the rapid calcium influx in OLE cells following P4 stimulation is mediated by the nuclear or membrane receptor or perhaps a combination of both. Although P4 is well-documented to increase intracellular calcium rapidly in several cell types, the roles of nuclear and membrane PRs are still unresolved (Wasserman et al. 1980, Thomas & Meizel 1989). For example, the nPR can interact with intracellular signaling machinery to mediate non-genomic effects of P4, while other studies have shown mPRs can alter calcium signaling (Ashley et al. 2006, Boonyaratanakornkit & Edwards 2007, Lee et al. 2010, Singh et al. 2013). Further studies are clearly necessary to determine the mechanism by which P4 activates L-type channels to regulate calcium influx in OLE cells.

In summary, our work shows that P4 initiates a rapid calcium influx through L-type calcium channels that stimulate PAD2 nuclear translocation and histone citrullination to help regulate IGFBP1 expression. These studies demonstrate that PADs play an important role in epigenetic gene regulation in uterine luminal epithelium and further, our knowledge of transcriptional regulation of the important histotroph gene IGFBP1. Understanding the epigenetic mechanisms regulating histotroph genes like IGFBP1 may lead to future fertility therapeutics to prevent recurrent pregnancy loss in multiple species.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under the Award Number P20GM103432 (B D C), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Childhood Health and Disease R21HD090541 (B D C and A M N), NIH NIGMS P20-121310-03 (B T), and in part by R35 GM118112 (P R T). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author contribution statement

Conceptualization was done by C H Y, A M N, B T and B D C; methodology was given by C H Y, B T and B D C; validation was done by C H Y and A M; formal analysis was done by C H Y, B S, A M and S B D; investigation was carried out by C H Y and B D C; resources were provided by V V N and P R T; data curatio was done by B D C; writing – original draft preparation was done by C H Y; writing – review and editing was done by C H Y and B D C; visualization was done by C Y H, B S, S B D and B D C; supervision and project administration were done by B D C; funding acquisition was done by B D C and P R T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Arita K, Hashimoto H, Shimizu T, Nakashima K, Yamada M, Sato M.2004. Structural basis for Ca(2+)-induced activation of human PAD4. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology 11 777–7. ( 10.1038/nsmb799) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley RL, Clay CM, Farmerie TA, Niswender GD, Nett TM.2006. Cloning and characterization of an ovine intracellular seven transmembrane receptor for progesterone that mediates calcium mobilization. Endocrinology 147 4151–415. ( 10.1210/en.2006-0002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley RL, Arreguin-Arevalo JA, Nett TM.2009. Binding characteristics of the ovine membrane progesterone receptor alpha and expression of the receptor during the estrous cycle. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 7 42. ( 10.1186/1477-7827-7-42) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banu SK, Lee J, Stephen SD, Nithy TK, Arosh JA.2010. Interferon tau regulates PGF2alpha release from the ovine endometrial epithelial cells via activation of novel JAK/EGFR/ERK/EGR-1 pathways. Molecular Endocrinology 24 2315–23. ( 10.1210/me.2010-0205) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T, Troup DB, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Rudnev D, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Soboleva A, Tomashevsky M, Marshall KA. et al. 2009. NCBI GEO: archive for high-throughput functional genomic data. Nucleic Acids Research 37 D885–D8. ( 10.1093/nar/gkn764) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazer FW.1975. Uterine protein secretions: relationship to development of the conceptus. Journal of Animal Science 41 1376–13. ( 10.2527/jas1975.4151376x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezy O, Vernochet C, Gesta S, Farmer SR, Kahn CR.2007. TRB3 blocks adipocyte differentiation through the inhibition of C/EBPbeta transcriptional activity. Molecular and Cellular Biology 27 6818–68. ( 10.1128/MCB.00375-07) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonyaratanakornkit V, Edwards DP. 2007. Receptor mechanisms mediating non-genomic actions of sex steroids. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 25 139–1. ( 10.1055/s-2007-973427) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks K, Burns G, Spencer TE.2014. Conceptus elongation in ruminants: roles of progesterone, prostaglandin, interferon tau and cortisol. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 5 53. ( 10.1186/2049-1891-5-53) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrington BD, Zhang X, McElwee JL, Morency E, Anguish LJ, Coonrod SA.2012. Potential role for PAD2 in gene regulation in breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE 7 e41242. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0041242) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PL, Moore JJ, Lundgren DW, Choobineh E, Chang SM, Chang AS.2000. Gestational changes in uterine L-type calcium channel function and expression in guinea pig. Biology of Reproduction 63 1262–12. ( 10.1095/biolreprod63.5.1262) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang AK, Murtazina DA, Magee C, Navratil AM, Clay CM, Amberg GC.2014. GnRH evokes localized subplasmalemmal calcium signaling in gonadotropes. Molecular Endocrinology 28 2049–20. ( 10.1210/me.2014-1208) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dante G, Vaccaro V, Facchinetti F.2013. Use of progestagens during early pregnancy. Facts, Views and Vision in ObGyn 5 66–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq K, Vriens J. 2018. Establishing life is a calcium-dependent TRiP: transient receptor potential channels in reproduction. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta: Molecular Cell Research 1865 1815–1829. ( 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.08.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diskin MG, Murphy JJ, Sreenan JM.2006. Embryo survival in dairy cows managed under pastoral conditions. Animal Reproduction Science 96 297–311. ( 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2006.08.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon AB, Knights M, Winkler JL, Marsh DJ, Pate JL, Wilson ME, Dailey RA, Seidel G, Inskeep EK.2007. Patterns of late embryonic and fetal mortality and association with several factors in sheep. Journal of Animal Science 85 1274–12. ( 10.2527/jas.2006-129) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressing GE, Goldberg JE, Charles NJ, Schwertfeger KL, Lange CA.2011. Membrane progesterone receptor expression in mammalian tissues: a review of regulation and physiological implications. Steroids 76 11–1. ( 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.09.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards BS, Dang AK, Murtazina DA, Dozier MG, Whitesell JD, Khan SA, Cherrington BD, Amberg GC, Clay CM, Navratil AM.2016. Dynamin is required for GnRH signaling to L-type calcium channels and activation of ERK. Endocrinology 157 831–8. ( 10.1210/en.2015-1575) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filant J, Spencer TE. 2013. Endometrial glands are essential for blastocyst implantation and decidualization in the mouse uterus. Biology of Reproduction 88 93. ( 10.1095/biolreprod.113.107631) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler DJ, Nicolaides KH, Miell JP.2000. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1): a multifunctional role in the human female reproductive tract. Human Reproduction Update 6 495–504. ( 10.1093/humupd/6.5.495) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Mazella J, Suwanichkul A, Powell DR, Tseng L.1999. Activation of the insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 promoter by progesterone receptor in decidualized human endometrial stromal cells. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 153 11–1. ( 10.1016/s0303-7207(9900096-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson LM, Chakraborty C, McKinnon T, Lala PK.2001. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 stimulates human trophoblast migration by signaling through alpha 5 beta 1 integrin via mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 86 2484–24. ( 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7532) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard LM, Murphy TJ, Org T, Enciso JM, Hashimoto-Partyka MK, Warren CM, Domigan CK, McDonald AI, He H, Sanchez LA. et al. 2014. Progesterone receptor in the vascular endothelium triggers physiological uterine permeability preimplantation. Cell 156 549–5. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.025) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CA, Taylor KM, Ramsey WS, Hill JR, Bazer FW, Bartol FF, Spencer TE.2001. Endometrial glands are required for preimplantation conceptus elongation and survival. Biology of Reproduction 64 1608–16. ( 10.1095/biolreprod64.6.1608) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara T, Nakashima K, Hirano H, Senshu T, Yamada M.2002. Deimination of arginine residues in nucleophosmin/B23 and histones in HL-60 granulocytes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 290 979–9. ( 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6303) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horibata S, Vo TV, Subramanian V, Thompson PR, Coonrod SA.2015. Utilization of the soft agar colony formation assay to identify inhibitors of tumorigenicity in breast cancer cells. Journal of Visualized Experiments 99 e52727. ( 10.3791/52727) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Newton GR, Bazer FW, Spencer TE.1999. Development and characterization of immortalized ovine endometrial cell lines. Biology of Reproduction 61 1324–13. ( 10.1095/biolreprod61.5.1324) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MT, Morgan PM, Coonan C.1997. Peptide growth factors and preimplantation development. Human Reproduction Update 3 137–1. ( 10.1093/humupd/3.2.137) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai Y, Tsutsumi O, Taketani Y, Endo M, Iino M.1995. Stretch-induced enhancement of contractions in uterine smooth muscle of rats. Journal of Physiology 486 373–3. ( 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020819) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavlashvili T, Jia Y, Dai D, Meng X, Thiel KW, Leslie KK, Yang S.2016. Inverse relationship between progesterone receptor and Myc in endometrial cancer. PLoS ONE 11 e0148912. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0148912) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SA, Edwards BS, Muth A, Thompson PR, Cherrington BD, Navratil AM.2016. GnRH stimulates peptidylarginine deiminase catalyzed histone citrullination in gonadotrope cells. Molecular Endocrinology 30 1081–1091. ( 10.1210/me.2016-1085) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Buzzio OL, Li S, Lu Z.2005. Role of FOXO1A in the regulation of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 in human endometrial cells: interaction with progesterone receptor. Biology of Reproduction 73 833–83. ( 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043182) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JS, Subramanian V, O'Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Smith CK, Hodgin JB, Thompson PR, Kaplan MJ.2015. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition disrupts NET formation and protects against kidney, skin and vascular disease in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 74 2199–2. ( 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205365) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Kumari S, Majhi RK, Swain N, Yadav M, Goswami C.2015. Regulation of TRP channels by steroids: implications in physiology and diseases. General and Comparative Endocrinology 220 23–32. ( 10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.10.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusama K, Yoshie M, Tamura K, Imakawa K, Isaka K, Tachikawa E.2015. Regulatory action of calcium ion on cyclic AMP-enhanced expression of implantation-related factors in human endometrial cells. PLoS ONE 10 e0132017. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0132017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak-Kim J, Park JC, Ahn HK, Kim JW, Gilman-Sachs A.2010. Immunological modes of pregnancy loss. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 63 611–6. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00847.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BM, Lee GS, Jung EM, Choi KC, Jeung EB.2009. Uterine and placental expression of TRPV6 gene is regulated via progesterone receptor- or estrogen receptor-mediated pathways during pregnancy in rodents. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 7 49. ( 10.1186/1477-7827-7-49) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KL, Dai Q, Hansen EL, Saner CN, Price TM.2010. Modulation of ATP-induced calcium signaling by progesterone in T47D-Y breast cancer cells. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 319 109–1. ( 10.1016/j.mce.2010.01.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal S, Thompson PR. 2019. Protein arginine deiminases (PADs): biochemistry and chemical biology of protein citrullination. Accounts of Chemical Research 52 818–832. ( 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramathal CY, Bagchi IC, Taylor RN, Bagchi MK.2010. Endometrial decidualization: of mice and men. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 28 17–26. ( 10.1055/s-0029-1242989) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechter D, Dormann HL, Allis CD, Hake SB.2007. Extraction, purification and analysis of histones. Nature Protocols 2 1445–14. ( 10.1038/nprot.2007.202) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons RM, Erikson DW, Kim J, Burghardt RC, Bazer FW, Johnson GA, Spencer TE.2009. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 in the ruminant uterus: potential endometrial marker and regulator of conceptus elongation. Endocrinology 150 4295–4. ( 10.1210/en.2009-0060) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Su C, Ng S.2013. Non-genomic mechanisms of progesterone action in the brain. Frontiers in Neuroscience 7 159. ( 10.3389/fnins.2013.00159) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE.2014. Biological roles of uterine glands in pregnancy. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 32 346–3. ( 10.1055/s-0034-1376354) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Gray CA. 2006. Sheep uterine gland knockout (UGKO) model. Methods in Molecular Medicine 121 85–94. ( 10.1385/1-59259-983-4:083) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Bazer FW.2004. Progesterone and placental hormone actions on the uterus: insights from domestic animals. Biology of Reproduction 71 2–10. ( 10.1095/biolreprod.103.024133) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Forde N, Lonergan P.2016. The role of progesterone and conceptus-derived factors in uterine biology during early pregnancy in ruminants. Journal of Dairy Science 99 5941–5950. ( 10.3168/jds.2015-10070) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahara H, Tsuchida M, Kusubata M, Akutsu K, Tagami S, Sugawara K.1989. Peptidylarginine deiminase of the mouse. Distribution, properties, and immunocytochemical localization. Journal of Biological Chemistry 264 13361–1336. ( 10.1016/S0021-9258(1851637-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahara H, Kusubata M, Tsuchida M, Kohsaka T, Tagami S, Sugawara K.1992. Expression of peptidylarginine deiminase in the uterine epithelial cells of mouse is dependent on estrogen. Journal of Biological Chemistry 267 520–52. ( 10.1016/S0021-9258(1848526-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura I, Jozaki K, Sato S, Shirafuta Y, Shinagawa M, Maekawa R, Taketani T, Asada H, Tamura H, Sugino N.2018. The distal upstream region of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 enhances its expression in endometrial stromal cells during decidualization. Journal of Biological Chemistry 293 5270–5280. ( 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000234) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanikawa C, Espinosa M, Suzuki A, Masuda K, Yamamoto K, Tsuchiya E, Ueda K, Daigo Y, Nakamura Y, Matsuda K.2012. Regulation of histone modification and chromatin structure by the p53–PADI4 pathway. Nature Communications 3 676. ( 10.1038/ncomms1676) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazuke SI, Mazure NM, Sugawara J, Carland G, Faessen GH, Suen LF, Irwin JC, Powell DR, Giaccia AJ, Giudice LC.1998. Hypoxia stimulates insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 (IGFBP-1) gene expression in HepG2 cells: a possible model for IGFBP-1 expression in fetal hypoxia. PNAS 95 10188–101. ( 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10188) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terakawa H, Takahara H, Sugawara K.1991. Three types of mouse peptidylarginine deiminase: characterization and tissue distribution. Journal of Biochemistry 110 661–66. ( 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123636) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Meizel S. 1989. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis in human sperm stimulated with follicular fluid or progesterone is dependent upon Ca2+ influx. Biochemical Journal 264 539–5. ( 10.1042/bj2640539) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viero C, Mechaly I, Aptel H, Puech S, Valmier J, Bancel F, Dayanithi G.2006. Rapid inhibition of Ca2+ influx by neurosteroids in murine embryonic sensory neurones. Cell Calcium 40 383–3. ( 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li M, Stadler S, Correll S, Li P, Wang D, Hayama R, Leonelli L, Han H, Grigoryev SA. et al. 2009. Histone hypercitrullination mediates chromatin decondensation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Journal of Cell Biology 184 205–2. ( 10.1083/jcb.200806072) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman WJ, Pinto LH, O'Connor CM, Smith LD.1980. Progesterone induces a rapid increase in [Ca2+]in of Xenopus laevis oocytes. PNAS 77 1534–153. ( 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1534) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young CH, Rothfuss HM, Gard PF, Muth A, Thompson PR, Ashley RL, Cherrington BD.2017. Citrullination regulates the expression of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 (IGFBP1) in ovine uterine luminal epithelial cells. Reproduction 153 1–10. ( 10.1530/REP-16-0494) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Nagar M, Maurais AJ, Slade DJ, Parelkar SS, Coonrod SA, Weerapana E, Thompson PR.2019. Calcium regulates the nuclear localization of protein arginine deiminase 2. Biochemistry 58 3042–3056. ( 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00225) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a