Abstract

Platinum resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer (OvCa) is rising at an alarming rate, with recurrence of chemo-resistant high grade serous OvCa (HGSC) in roughly 75% of all patients. Additionally, HGSC has an abysmal five-year survival rate, standing at 39% and 17% for FIGO stages III and IV, respectively. Herein we review the crucial cellular interactions between HGSC cells and the cellular and non-cellular components of the unique peritoneal tumor microenvironment (TME). We highlight the role of the extracellular matrix (ECM), ascitic fluid as well as the mesothelial cells, tumor associated macrophages, neutrophils, adipocytes and fibroblasts in platinum-resistance. Moreover, we underscore the importance of other immune-cell players in conferring resistance, including natural killer cells, myeloid-derived suppressive cells (MDSCs) and T-regulatory cells. We show the clinical relevance of the key platinum-resistant markers and their correlation with the major pathways perturbed in OvCa. In parallel, we discuss the effect of immunotherapies in re-sensitizing platinum-resistant patients to platinum-based drugs. Through detailed analysis of platinum-resistance in HGSC, we hope to advance the development of more effective therapy options for this aggressive disease.

Keywords: OvCa, TME, ascitic fluid, cisplatin-resistance

1. Introduction

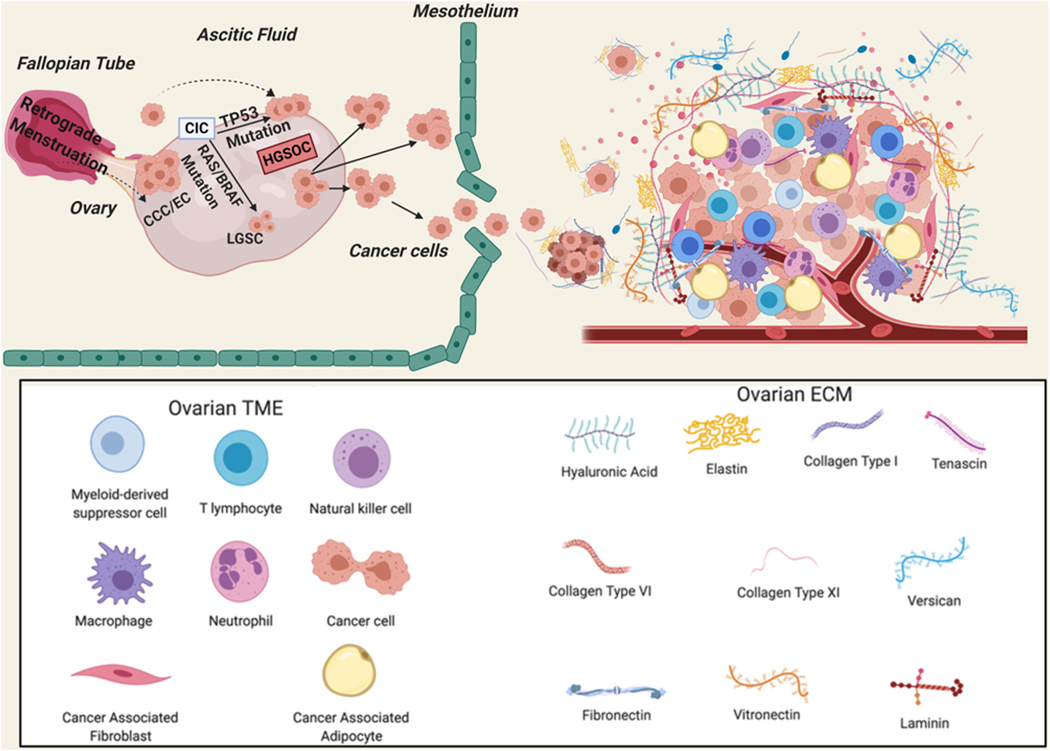

Epithelial ovarian cancer (OvCa) is the most common gynecologic malignancy, with estimated 21,750 new cases and 13,940 deaths in the United States in 2020 [1]. Strikingly, at the time of diagnosis, the 5-year survival rate is approximately 30%, as most patients present with advanced stages (III or IV) [2]. High grade serous cancer (HGSC) is the most common subtype comprising ~ 75% of cases. Standard of care entails initial complete cytoreductive surgery with subsequent treatment with chemotherapeutic agents, typically a platinum and taxane doublet [3, 4]. The most challenging factors contributing to the abysmal outcomes of OvCa patients are suboptimal surgical resection of the widespread tumor in the peritoneal cavity and the progressive rise of platinum resistance in HGSC [3, 4]. While initial response rates are encouraging, nearly 70% of patients with advanced disease relapse within two years with limited treatment options [5]. Moreover, platinum-resistance is also associated with resistance to other non-platinum chemotherapeutic agents, further compounding disease outcome [6]. Patients who initially respond to platinum agents foster tumors with intra-tumoral heterogeneity composed not only of sensitive cells but also intrinsically platinum-resistant cells. In primary platinum-resistance, a subpopulation of sensitive cells undergoes apoptosis following platinum therapy, while the resistant cells survive and expand [7]. However, in acquired resistance, after several treatment rounds of chemotherapy, residual numbers of platinum-sensitive cells can continue to thrive due to phenotypic plasticity. Such cells can either acquire mutations that confer resistance or are outnumbered by inherently resistant cells [8]. Both are attributed to the unique characteristic of OvCa to metastasize mainly in the peritoneal cavity where OvCa cells not only survive as implants on the abdominal organs mainly the mesothelium and omental fat pad, but also as floating single or multi-cellular spheroids, which can subsequently thrive in the complex microenvironmental network composed of stromal and immune cells as well as extracellular matrix (ECM) components [9–11] (Figure 1). Recurrent cases have been divided based on platinum free interval (PFI), or the time between completion of platinum adjuvant treatment and disease recurrence into: 1) intrinsically resistant HGSC tumors with PFI less than 6 months, or 2) acquired resistant HGSC tumors with PFI more than 6 months. While patients with recurrence with PFI greater than 6 months may still fall under the category of “platinum sensitive”, such individuals will most likely become platinum resistant with time and their PFI becomes less than 6 months [12].

Figure 1: Schematic illustration of the cell(s) of origin of ovarian cancer as well as stromal cells, ECM components, and immune Cells Involved in OvCa platinum-resistance.

OvCa cells originate from the ovarian surface epithelium or the surface epithelium of the Fallpian tubes. HGSC: high grade serous ovarian cancer; LGSC: low grade serous cancer; CIC: carcinoma in situ; CCC: clear cell carcinoma; EC: endometroid cancer; ECM: extracellular matrix.

Platinum resistance has been attributed to several factors including reduced platinum uptake into the cell, increased efflux, and intracellular inactivation [13–15] In addition, the perturbed survival signaling pathways in OvCa cells lead to an increase in DNA repair [5] and reactivation of OvCa cells that survived cisplatin therapy including cancer stem cells [15–17].

Platinum-based chemotherapeutics are transported inside the cells by copper transporters 1 and 2 (CTR1 and CTR2), that are encoded by the SLC31A1 and SLC31A2 genes, respectively [18–24]. High expression of SLC31A1 but not SLC31A2 (Figure 2) in patients’ tumors positively correlates with patients’ survival and platinum therapy. On the other hand, cellular efflux of platinum agents is mediated through copper exporters, ATPases A and B that hinder the interaction of platinum agents with nuclear DNA [21]. ATP7A and ATP7B are highly expressed in cisplatin-resistant OvCa cell lines and correlate with platinum resistance in many cancers including OvCa [25–32], with high ATP7A transcripts negatively correlating with patients’ survival and platinum treatment (Figure 2). Furthermore, platinum-resistant tumor cells overexpress cellular scavenger and detoxification enzymes [33, 34] as glutathione (gamma-glutamylcysteinylglycine: GSH), which detoxifies cisplatin and its analogues [35] and GSH-S-transferase Pi (GSTP1) which inactivates cisplatin through conjugation of thiol groups of reduced glutathione to cisplatin, and γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (CGCS). CGCS expression negatively correlated with patients’ survival and platinum therapy (Figure 2) and has been correlated with cisplatin resistance in OvCa cell lines [36, 37]; whereas GSTP1 did not correlate with disease outcome.

Figure 2: Association between cisplatin uptake and export transporters, and catabolic enzyme and patients’ survival.

Kaplan Meier’s curves showing the association between the expression of cisplatin-uptake transporter, SLC31A1, A-E, cisplatin-efflux transporter, ATP7A, B-F, and cisplatin-inactivating enzyme, GCS, C-G, and overall patients survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), respectively in platinum-treated patients with HGSC stages 2+3+4. Tables in D-H indicate the values used in the calculation of OS and PFS, respectively. Significance was deemed at *p<0.05. Graphs were generated from KM Plot (https://www.kmplot.com) [244] with JetSet probe set selected.

Several tumor microenvironmental (TME) factors influence OvCa response to platinum therapy. The unique OvCa TME involves a vast array of interconnected and complex networks of advanced crosstalk between OvCa cells and stromal cells as cancer associated adipocytes, fibroblasts, mesothelial cells, and immune cells including macrophages, neutrophils, natural killer (NK) cells, polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, as well as components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and ascitic fluid, all of which partake not only in propagating cell survival, and invasiveness [38–40], but also play a pivotal role in platinum uptake/export machinery, OvCa survival machinery and oncogenic pathways in tumor cells [36].

2. Oncogenic signaling pathways in OvCa.

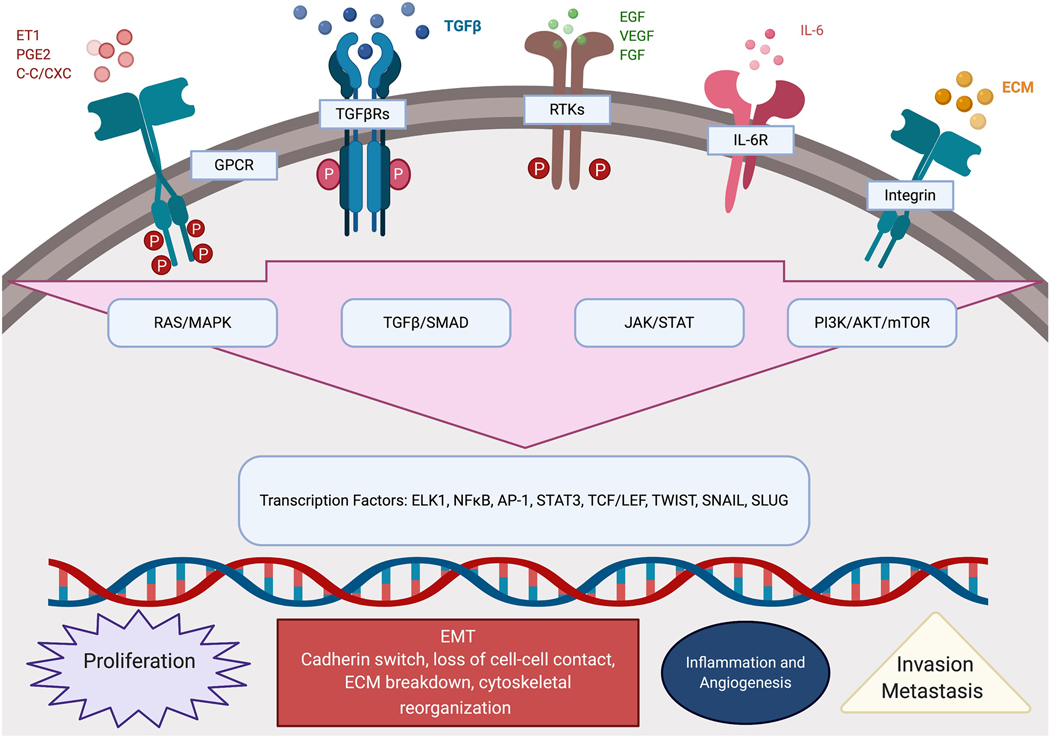

Several genomic and proteomic studies identified the molecular drivers of HGSC and the mechanisms of evolution of platinum-resistance. Integration of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and phosphoproteomics data further highlighted the amplification/ hyperactivation of RAS oncogene/ RAF proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase (RAF1)/mitogen activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)/ extracellular receptor kinases (ERK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K), and receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) pathways that further activate multiple interconnected oncogenic pathways including protein kinase B (AKT)-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), transforming growth factor β (TGFβ)-SMADs, Janus kinases/Signal transducers and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT), and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFkB) pathways [41, 42] (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Schematic illustration of the interconnected activated signaling pathways implicated in disease progression and platinum resistance.

Endothelin-1 (ET1); prostaglandin E2 (PGE2); β/α-chemokine (C-C/CXC); G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR); transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ); transforming growth factor beta Receptor (TGFβR); epidermal growth factor (EGF); vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF); fibroblast growth factor (FGF); receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK); interleukin 6 (IL-6); interleukin 6 receptor (IL-6R); extracellular matrix (ECM); Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase(RAS/MAPK); transforming growth factor beta/suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic (TGFβ/SMAD); Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT); phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR); ETS Like-1 (ELK1) nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB); activator protein 1 (AP-1); signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3); T-cell specific transcription factor/lymphoid enhancer binding Factor (TCF/LEF); twist-related protein 1 (TWIST); zinc finger protein SNAI1 (SNAIL); zinc finger protein SNAI1 (SLUG); epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT).

The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, has been long implicated in OvCa survival, epithelial mesenchymal transition, invasiveness, angiogenesis as well as platinum resistance [43, 44]. In addition to the activating mutations in RAS and RAF oncogenes, The Cancer Genome Atas (TCGA) indicated that extracellular receptor kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1 and ERK2) and mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK) are amplified in 16% and 21% of OvCa cases, respectively [41]. High transcript levels of RAF1, ERK1 and ERK2 significantly correlated with poor platinum-free survival in platinum-treated patients with advanced stage (stage 2+) HGSC (Figure 4). RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway is activated by paracrine or autocrine growth factors activating their cognate RTKs (summarized in [45]). This pathway is also activated by ECM interactions with integrins transducing the ECM-integrin-dependent signal with subsequent activation and autophosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and integrin-like kinase (ILK) [46]. The interactions of ECM molecules as fibronectin and vitronectin with their cognate integrins also activate RTKs-ERK1/2 MAPKs, thus favoring the RTK-induced migration and invasion [46]. Furthermore, ERK/MAPK pathway is activated by GPCRs binding to their agonist ligands as cytokines/chemokines (C-C and C-X-C families) [47], bioactive lipids (lysophosphatidic acid, LPA, and prostaglandins, PGs) [48–55], hormone receptors (summarized in [56]), and neuroendocrine peptide hormones (endothelin, and angiotensin) [57–59]. The activation of G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) induces MAPK activation through activation of PI3K-AKT, RAS/RAF/MEK as well as transactivation of RTKs and other membrane receptors [60]. The cross-talk and activation/transactivation cascades activate a plethora of downstream targets including transcription factors inducing steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1), ETS domain-containing protein (Elk-1), activator protein-1 (AP1, cJun and c-Fos), avian myelocytomatosis virus oncogene cellular homolog (c-Myc), Janus kinases 1–2 (JAK1/2) and signal transducers and activator of transcription (STATs) as well as TGFβ-SMAD pathway [45]. All induce broad spectrum target genes involved in cell proliferation, survival, migration, and invasiveness, angiogenesis, as well as chemoresistance [45]. It is noteworthy that molecular characterization of platinum-resistant HGSC identified that the aforementioned pathways are key pathways implicated in chemo-resistance [43, 61–63]. Of note, the activation of these pathways occurs not only in tumor cells but is also reciprocated by other cellular components of the unique OvCa TME. Most of the downstream targets are secreted in the ascitic fluid instigating autocrine and paracrine activation of the oncogenic signaling pathways in the various cell types with subsequent modulation of their phenotype, creating a vicious circle leading to therapeutic resistance, recurrence, and poor survival [64–66] (Figure 3).

Figure 4: Correlation of RAF1/ ERK1/2 pathway with survival of platinum-treated HGSC patients.

A-C. Kaplan Meier’s curves showing the association between RAF1/MAPK pathway and overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), respectively of platinum-treated patients with HGSC stages 2+3+4. Tables in B-D indicate the values used in the calculation of OS and PFS, respectively. Significance was deemed at *p<0.05. Graphs were generated from KM Plot (https://www.kmplot.com) [244] with JetSet probe set selected.

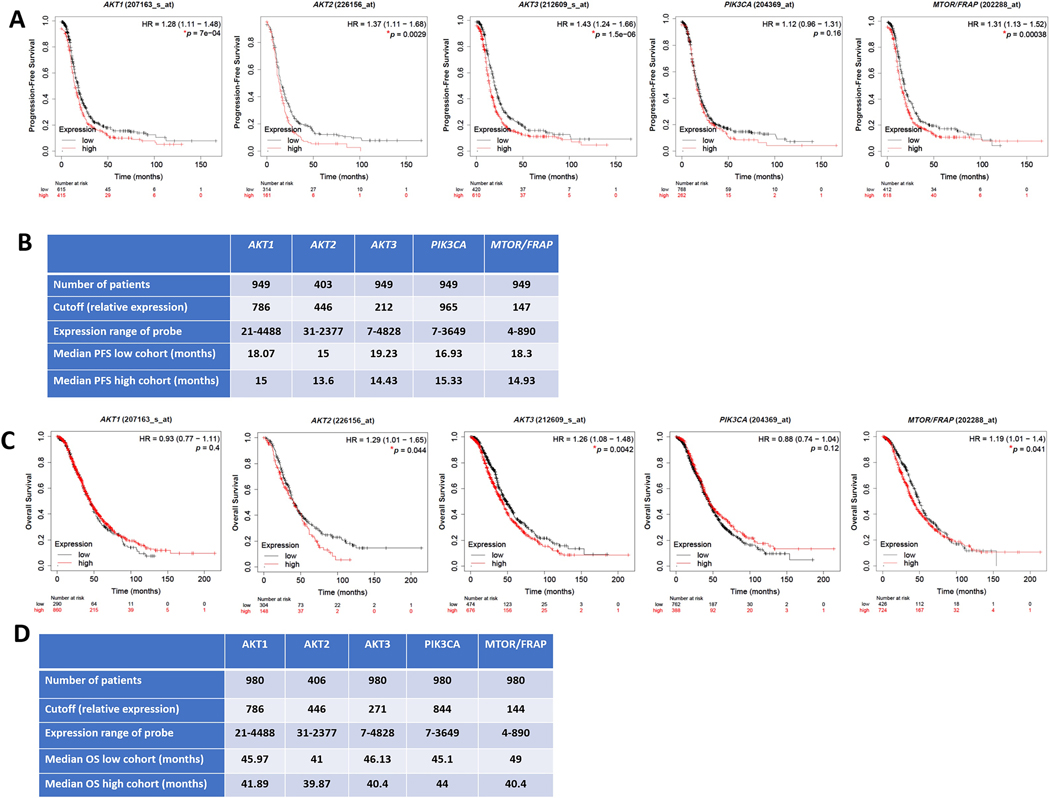

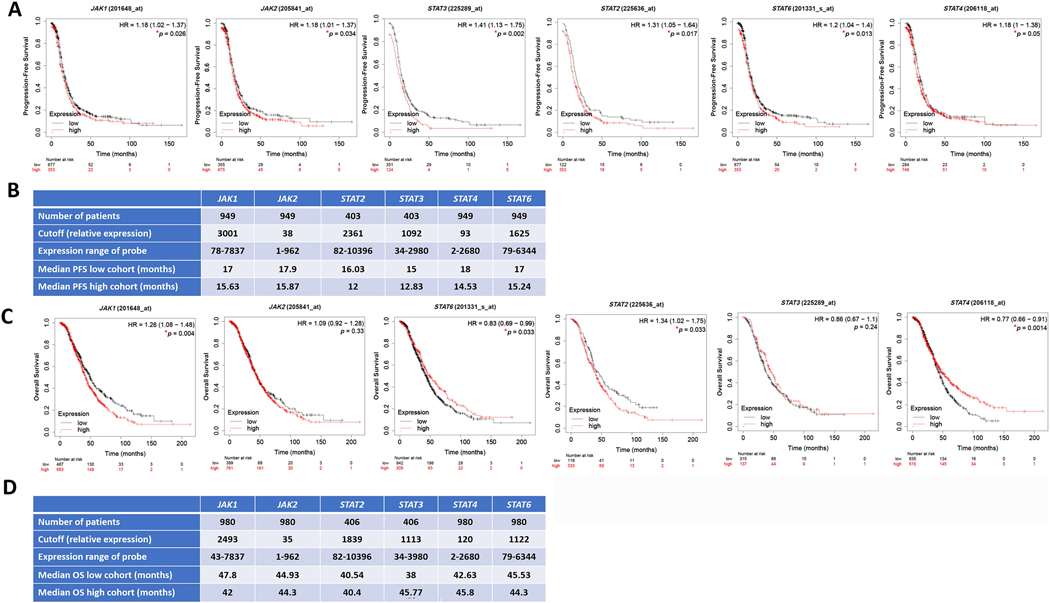

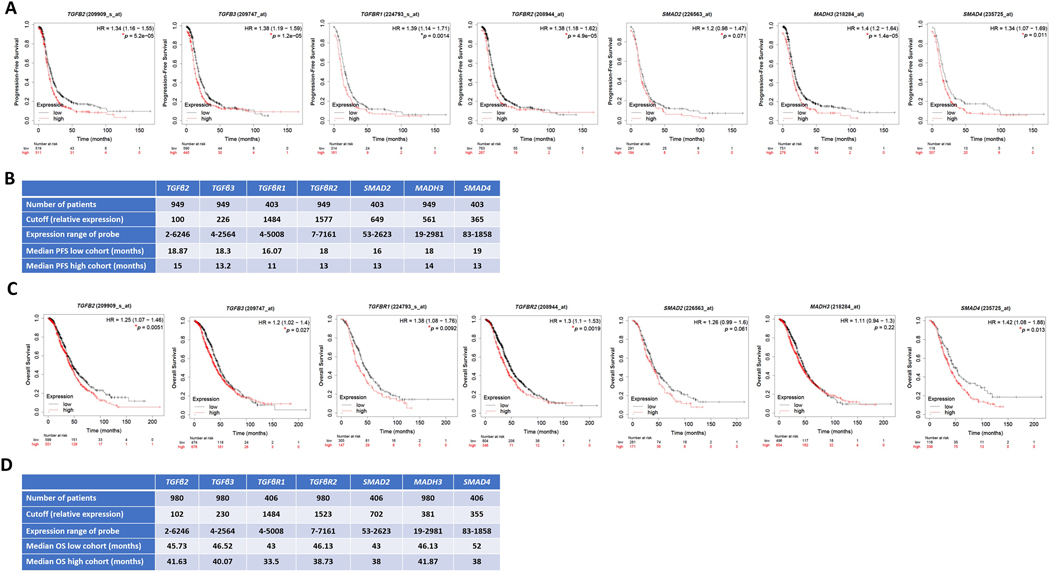

Importantly, analysis of tumors of platinum-treated patients with HGSC using KM-plot (https://kmplot.com) [67] that included OvCa transcriptomic datasets Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [68] revealed that in platinum-treated patients, high transcript levels of key regulators in MAPK pathway (RAF1, MAPK1/ERK2 and MAPK3/ERK1) correlate with poorer survival in cisplatin-treated patients with HGSC (Figure 4). Similarly, high transcripts of key regulators in the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway (AKT1, AKT2, AKT3, and MTOR) correlated with poorer survival in platinum-treated patients (Figure 5). In further support of this, high levels of key regulators were identified in the JAK/STAT pathway (Figure 6). Consistently, high transcripts of key regulators in the TGFβ-SMAD pathway (TGFβ2, TGFβ3, TGFβR1/2, and SMAD2–4) correlated with poorer survival outcomes (Figure 7).

Figure 5: Correlation of PI3K/AKT/MTOR pathway with survival of platinum-treated HGSC patients.

Kaplan Meier’s curves showing the association between PI3K/AKT/MTOR pathway and overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), respectively of platinum-treated patients with HGSC stages 2+3+4. Tables in B-D indicate the values used in the calculation of OS and PFS, respectively. Significance was deemed at *p<0.05. Graphs were generated from KM Plot (https://www.kmplot.com) [244] with JetSet probe set selected.

Figure 6: Correlation of JAK/STAT pathway with survival of platinum-treated HGSC patients.

Kaplan Meier’s curves showing the association between JAK/STAT pathway and overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), respectively of platinum-treated patients with HGSC stages 2+3+4. Tables in B-D indicate the values used in the calculation of OS and PFS, respectively. Significance was deemed at *p<0.05. Graphs were generated from KM Plot (https://www.kmplot.com) [244] with JetSet probe set selected.

Figure 7: Correlation of TGFβ/TGFβRs/SMAD pathway with survival of platinum-treated HGSC patients.

Kaplan Meier’s curves showing the association between TGFβ/TGFβRs/SMAD pathway and overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), respectively of platinum-treated patients with HGSC stages 2+3+4. Tables in B-D indicate the values used in the calculation of OS and PFS, respectively. Significance was deemed at *p<0.05. Graphs were generated from KM Plot (https://www.kmplot.com) [244] with JetSet probe set selected.

3. The Ovarian Cancer Tumor Microenvironment

OvCa is unique from other epithelial malignancies in that it metastasizes mainly within the peritoneal cavity [39]. Once tumor cells detach from the ovary or Fallopian tube surface epithelium, their primary sites of origin, they adhere to the mesothelial layer of the peritoneal covering of the abdominal organs, and invade through the sub-mesothelial layer to form metastatic implants in the omentum [69, 70] (Figure 1). Importantly, OvCa cells have the unique ability to survive as floaters in the nutrient-, and growth factor-rich ascitic fluid either as single cells or multi-cellular spheroids [39]. In addition, the OvCa TME is composed of ECM (ECM), mesothelial cells, endothelial cells, bone marrow derived cells, adipose cells, immune and inflammatory cells, as well as fibroblasts and myofibroblasts [71–74]. Signaling molecules secreted from multi-stromal cells in the TME lead to the persistent activation of the aforementioned signaling pathways and consequently promote tumor progression [54, 72, 75–79] (Figure 1).

4. Extracellular Matrix-Dependent Platinum Resistance

The normal ovarian and peritoneal ECM consist of an intricate network of macromolecules composed of proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), hyaluronan, collagens, fibronectin, vitronectin, elastin, laminins, and several other glycoproteins [80–83]. The main role of the ECM is maintaining the structural integrity of tissues; however, it is also involved in the regulation of cell migration, growth, protein synthesis, and secretion [80, 84]. In the OvCa TME, the activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) and macrophages is associated with excessive ECM remodeling with upregulation of ECM proteins; subsequent crosslinking and degrading enzymes lead to ECM stiffness which promote cancer cell adhesion, migration and invasiveness as well as angiogenesis. Nevertheless, ECM molecules are also implicated in the initiation and regulation of cell signaling through their interaction with numerous cell surface molecules including integrins, intracellular and vascular cell adhesion molecules (ICAM and VCAM), discoidin domain proteins, and syndecans [80, 85]. Excessive ECM remodeling results in chemoresistance, particularly platinum resistance, through activation and transactivation of integrin-, growth factor-, and cytokine-mediated signaling pathways that are involved in tumor growth, and survival [80, 86, 87] (Figure 3). In support of this, inhibition of ECM-integrin signaling via focal adhesion kinase (FAK) inhibition mitigated platinum resistance and induced apoptosis signifying the crucial role of ECM-cell interaction in OvCa cells’ response to platinum agents [88]. Consistently, growing OvCa cells on collagen type I decreased their response to cisplatin, an effect that was mitigated by inhibition of integrin-linked kinase (ILK) which re-sensitized cells on collagen to cisplatin [89].

Proteomic profiling of chemo-resistant OvCa patients’ samples revealed significant upregulation of ECM proteins including decorin, versican, basigin (CD147), fibulin-1, ECM protein 1, biglycan, fibronectin, dermatopontin, alpha smooth muscle actin, and an epidermal growth factor (EGF)-containing fibulin-like ECM protein 1 [90], all of which were also found to be upregulated in cisplatin-resistant OvCa cell lines [91]. In addition, COL6A3 transcript was not only highly upregulated in cisplatin-resistant cells, but its protein was also overexpressed in the peri-tumoral stroma of OvCa specimens and positively correlated with tumor grade. In vitro studies revealed that growing OvCa cells on COL6A3 conferred cisplatin-resistance [89, 91].

Carboplatin significantly increased expression of hyaluronic acid synthases (HAS2, HAS3) and hyaluronic acid (HA) secretion in the conditioned media of OvCa cell lines [92]. OvCa patients exhibited significantly higher serum HA levels after platinum-therapy compared with their pre-treatment levels. In addition, high serum pre-chemotherapy HA levels significantly predicted poor survival [92]. The expression of ABC drug transporters ABCB3, ABCC1, ABCC2, and ABCC3 was only significantly increased by HA for OvCa cells that expressed the HA- receptor CD44 [92]. The latter has been shown to co-localize with ABCC2 and ABCB1 in OvCa tissues, suggesting a functional link between HA-CD44 expression and chemoresistance [93]. For the expression of ABC transporters in OvCa cells, treatment with HA oligomers that made resistant SKOV3 cells more sensitive to carboplatin [92].

5. Mesothelial cells

The mesothelium serves as the initial barrier meeting metastatic OvCa cells. The recruitment of OvCa cells to mesothelial cells is initially caused by cancer cell and mesothelial cell secreted factors (secretomes). The expression of several pro-inflammatory mediators are induced when these secretomes precondition the mesothelial cell niche, with inflammatory chemokines and cytokines, bioactive lipids (e.g. LPA), ECM/integrins, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1), and CD44/HA (VCAM1) [54, 77, 94]. The complex bidirectional crosstalk between OvCa and mesothelial cells promotes OvCa cell adhesion and invasion, with an ensuing rise in proteases such as matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) as well as urokinase type plasminogen activator (uPA) and its receptor (uPAR) [49, 50, 54, 77, 94, 95], followed by mesothelial cell clearance as OvCa cells invade the sub-mesothelial space [11].

Platinum-resistant OvCa cells display increased adhesion and growth on the mesothelium and altered cell-cell junction, leading to enhanced OvCa cell dissemination and aggressiveness. These platinum resistant OvCa cells also exhibit decreased levels of DNA platination with more efficient repair of damaged DNA [96]. Mechanistic studies revealed that co-culture of OvCa and mesothelial cells induced platinum-resistance in OvCa cells through TGF-β1 and fibulin 1/AKT signaling pathways [97].

6. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)

Cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are induced in the TME by inflammation and hypoxia, to possess characteristics of both myofibroblasts and secretory phenotypes further contributing to a pro-tumorigenic TME [98–100]. The origin of CAFs in the OvCa milieu is still debatable as they may arise from resident fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells or de-differentiated adipocytes [100]. Importantly, CAF number positively correlates with a more advanced stage of OvCa, greater incidence of metastases in lymph nodes, and enhanced lymphatic volume [99]. The activation of CAF phenotype can be triggered by OvCa cells’ secreted factors including MMPs, reactive oxygen species (ROS), inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and TGFβ1 [98]. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)-induced CAF activation upregulates transforming growth factor α (TGFα) through a pro-inflammatory process involving NFκB. CAF-derived TGFα then activates epidermal growth factor (EGFR) instigating cancer cell growth [101]. Importantly, molecular crosstalk between CAFs and OvCa cells in the TME involves signaling from the TGFβ/TGFβ receptors (TGFβRs)/SMAD pathway in CAFs with subsequent upregulation and secretion of ECM molecules promoting tumor migration and invasion [65, 102]. The latter was mediated through the NFkB and JNK/STAT signaling pathways in OvCa cells further fostering a pro-inflammatory TME and OvCa aggressiveness [65]. CAFs were shown to induce EMT and chemo-resistance by secreting IL-6, resulting in pro-inflammatory transcription factors JAK/STAT, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (cEBPβ) and NFκB [81, 103, 104].

7. Cancer-Associate Adipoctes (CAAs)

OvCa cells shed in the peritoneal cavity hav a specific propensity to metastasize into the omentum, the fat pad that drapes the abdominal organs, as well as adipose tissue on the mesentery, around liver and kidney [105]. Adipocytes are the most important and abundant cellular component of omental and peritoneal adipose tissue [106]. Adipocytes in the vicinity of cancer cells are termed “cancer associated adipocytes, CAA” as they exhibit an inflammatory phenotype releasing cytokines/chemokines “adipokines” which contribute to OvCa cell metastatic colonization [105, 107, 108]. Metastasized OvCa cells resulted in an elevated expression of genes encoding fatty acid transport proteins such as CD36 and fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4), CD31, CD34, as well as vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1–2 (VEGFR1–2) [109, 110]. In return, OvCa through inflammatory secretome, fuel adipocyte metabolism by causing hydrolysis of triglycerides stored in adipocyte lipid droplets into free fatty acids (FFA) and glycerol which can in turn be used as energy for OvCa cells via β-oxidation to support the rapidly proliferating and invasive OvCa cells [70, 105, 107, 111–115].

The uptake of FFA released from CAA by OvCa cells has been shown to be mediated by FABP4 [105, 107]. This was supported by the delayed omental and peritoneal metastasis of OvCa in Fabp4-knockout mouse model as well as therapeutic delivery of small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting FABP4 [105, 116]. High FABP4 levels in human primary tumors are correlated with increased incidence of relapse after primary debulking surgery of HGSC, implicating FABP4 as a prognostic biomarker for OvCa recurrence [117]. Lipids transferred from adipocytes to OvCa cells were shown to augment FFA β-oxidation (FAO) in tumor cells [105, 109].

Importantly CAAs play an essential role in resistance of OvCa cells to platinum-chemotherapy through the secreted adipokines which activate the major oncogenic signaling pathways implicated in OvCa (Figure 3). Comprehensive lipidomic analysis also identified arachidonic acid (AA) as a strong chemo-protective lipid mediator in OvCa that not only exerts a direct activation of pro-survival oncogenic pathways but also through inhibition of cisplatin-induced apoptosis [114]. Another study by Zhu et al., reported that deletion of the transcription factor, NK2 Homeobox 8 (NKX2–8), a homeobox-containing developmental regulator, correlated with relapse-free survival of OvCa patients [118]. This study reported that genetic ablation of NKX2–8 activated the FAO pathway, resulting in platinum resistance and a higher recurrence rate of epithelial OvCa. FAO inhibitor perhexiline re-sensitized NKX2–8-depleted OvCa cells to cisplatin-chemotherapy, highlighting the key importance of NKX2–8 loss in reprogramming of FA metabolism–induced chemoresistance and potentially indicating a new treatment strategy for NKX2–8-deleted OvCa cells [118]. In another seminal study, adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSC) decreased the sensitivity of OvCa to cisplatin and inhibited cisplatin-mediated apoptosis [119].

In addition to increased FAO, OvCa exhibit significantly high expression of fatty acid synthase (FASN) which significantly correlated with tumor grade, stage, and poor prognosis [120]. Inhibition of FASN in platinum-resistant OvCa cells mitigated platinum resistance [121].

8. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)

During OvCa progression, macrophages are recruited to the peritoneal cavity, where they exhibit an extensive crosstalk with OvCa cells and are henceforth named “tumor-associated macrophages” (TAMs) [122, 123]. Within the peritoneum, macrophages are heavily populated in milky spots, the clusters of immune cell aggregates, embedded between adipocytes just under the mesothelial cell layer where they dictate OvCa tropism to the omentum [108, 124]. Traditionally, macrophages have been classified into either an M1 or M2 subtype where M1 macrophages are activated by the T helper cell type 1 (Th1) cytokine interferon-γ, lipopolysaccharides, and toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands. M1 macrophages foster adaptive immune responses via the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, and TNF-α. Phenotypically, M1 macrophages, express CD68, CD80, and CD86. Conversely, M2 macrophages are stimulated by T helper cell type 2 (Th2) cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-13, and secrete IL-10, TGF-β, and chemokines, all of which play a role in tissue remodeling, inflammation, and cancer progression. M2 macrophages express the markers CD163, CXC3R1, CD204, and CD206 [122, 125]. CD163 correlated with high levels of IL-6, and IL-10 in ascitic fluid, and poor prognosis in OvCa patients [126]. OvCa tissues exhibited significant increase in the numbers of CD68+ and CD206+ TAMS, and of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) expression, compared to benign ovarian tissues [127]. Comprehensive genome-wide expression profile of TAMs in patients with HGSC showed that TAMs exhibit an M1/M2 hybrid phenotype as they expressed both M2 markers, such as IL-10 and CD163, and M1 markers as CD86 and TNF-α [126]. Peritoneal M2 macrophages activate STAT3 signaling in OvCa cells which enhances the OvCa-TAM crosstalk and drives spheroid formation in the malignant ascitic fluid of aggressive OvCa [128–130]. M2 macrophages also secrete EGF and hence activate EGF/EGFR pathway with subsequent activation of VEGF-C/VEGFR3 signaling and integrin/ICAM-1 expression in the intraperitoneal TME, leading to OvCa cell proliferation, invasion, and widespread peritoneal dissemination [122, 131]. In addition, VEGF, TGF-β, MMPs, and adrenomedullin (ADM) secreted by TAMs enhance angiogenesis, vasculogenesis and vascular permeability [122, 126, 132–134]. In OvCa xenograft model, depletion of peritoneal macrophages but not neutrophils and NK cells significantly suppressed peritoneal metastasis of OvCa; further supporting the importance of TAMs in the initial phases of migration and homing. The pro-metastatic effect of peritoneal macrophages was mediated through VEGF production in the intraperitoneal milieu along with a plethora of soluble signaling molecules, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TGF-β, CCL18, CCL22, stromal-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α), VEGF, MMP-9, and heparin-binding-EGF (HB-EGF) [135–138]. Another unique feature of TAMs is the upregulation of genes linked to ECM remodeling and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) [132], all are mediated downstream of TAM-produced TGF-β, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), EGF as well as matrix degrading enzymes as MMPs, and uPA [139, 140].

Several studies have indicated that platinum-resistance are instigated by a plethora of TAM-associated cytokines [141–143]. Therefore, therapeutic altering TAM activity by targeting colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF-1R) signaling effectively enhanced platinum-induced anticancer activity, which was stimulated by an intra-tumoral type I interferon (IFN) response [141]. Cisplatin-resistance is associated with increased levels of IL-6 and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), two inflammatory mediators known to skew differentiation of monocytes to tumor-promoting IL-10-producing M2 macrophages [144]. These effects were mitigated by inhibition of the NFkB, cyclooxygenase (COX)-inhibitor, indomethacin, as well as functional blocking of interleukin-6 receptor (IL-6R) by tocilizumab [144] (Tables 1 and 2). Another study reported that transcription factor GATA3 mediated TAM polarization leading to release of exosomes that induced OvCa proliferation, migration, and cisplatin chemoresistance, suggesting that targeting of GATA3 may reverse platinum resistance [145]. Accordingly, classically activated macrophages promoted OvCa migration by augmenting Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20 (CCL20) production, and activation of its receptor, CCR6, on OvCa cells, leading to upregulated EMT machinery, invasiveness and metastasis [146]. Inhibition of CCL20 in cisplatin-treated macrophages and/or genetic inactivation of CCR6 in OvCa cells suppressed OvCa migration induced by cisplatin-polarized TAMs that leads to platinum- resistance in OvCa [146].

Table 1:

Markers of Cisplatin-resistance in pre-clinical and clinical models of OvCa

| Biomarker of Resistance | Cellular Mechanism | Source | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cycloxegenase-2 (COX-2) ↑ | Increases proliferation and inhibits apoptosis | Cell line | [229] |

| IL-6/IL-6R/sIL6R↑ | Proliferation, invasiveness, angiogenesis, and immune suppression | Cell line, ascites, tumors, plasma | [97, 216, 230, 231] |

| CCL2/MCP-1↑ | Proliferation, invasiveness, angiogenesis, macrophage recruitment (TAM phenotype), adhesion, immune suppression | Cell line, ascites, tumors, plasma | [46, 47, 139, 197, 232–234] |

| IL-8↑ | Proliferation, invasiveness, angiogenesis, macrophage recruitment (TAM phenotype), adhesion, immune suppression | Cell line, ascites, tumors, plasma | [88, 98, 209, 213, 230, 235, 236] |

| Insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF1R) ↑ | Inhibits apoptosis | Cell line | [237, 238] |

| Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (PI3K) ↑ | Inhibits apoptosis, proliferation, invasiveness | Cell line | [239, 240] |

| Isoform 1 of collagen XII alpha-1 chain (COL12A1) ↓ | Increases tumor angiogenesis and invasion | Cell line | [241, 242] |

| Collagen VI↑ | Survival, invasiveness and resistance | Cell lines, tumor tissue | [84, 205] |

| Pro-alpha1(XI) chain (COL11A1) ↑ | Increases invasion | Cell line | [241, 242] |

| Fibronectin (FN)↑ | Survival, invasiveness and resistance | Cell line, tumor tissues | [7, 62, 201, 243] |

| Periostin↑ | Survival, and cisplatin resistance | Cell line, tumor tissues | [243] |

| Vitronectin (VN)↑ | Survival, adhesion, metastasis, cisplatinresistance | Cell line, ascites, tumor tissues | [244] |

| Versican↑ | Survival, adhesion, invasion, inflammation, | Cell line, ascites, tumor tissues | [83] |

| Colony-stimulating-factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) ↑ | Inhibits apoptosis | Cell line | [245] |

| Leptin (LEP) ↑ | Inhibits apoptosis | Cell line | [246, 247] |

| Forkhead box M1 (FOXM1) ↑ | Increases cell-cycle progression, metastasis, and angiogenesis | Cell line | [224, 248] |

| Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFβ1) | Promotes EMT, angiogenesis, metastasis, and immunesuppression | Cell line, tissues, ascites | [248] |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) ↑ | Increases tumor angiogenesis | Cell lines, tissues, ascites | [249] |

| Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) ↑ | Increases inflammation, immune-suppression. | Cell lines, tissues, ascites | [250] |

| Mesothelium vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) ↑ | Regulates CD44 and multiple drug resistant gene ABCG2 | Cell line | [251] |

Table 2:

Clinical Trials targeting tumor microenvironment in advanced stage OvCa

| Drug | Target | Clinical Trial | NCT Trial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aflibercept (VEGF trap) | VEGF | Phase 2 |

NCT00327171

NCT00327444 NCT00396591 |

| Bevacizumab + paclitaxel and carboplatin | VEGF-A | Phase 3 | NCT01239732 |

| Bevacizumab + Carboplatin | VEGF-A | Phase 2 |

NCT00937560

NCT00744718 |

| Nintedanib + Bevacizumab | VEGFR1/2/3, FGFR1/2/3 and PDGFRα/β | Phase 1 | NCT02835833 |

| INCB062079 | FGFR4 | Phase 1 | NCT03144661 |

| Sorafinib + paclitaxel and carboplatin | Multi-targeted RTKi | Phase 2 | NCT00390611 |

| Sunitinib (SU11248) | Multi-targeted RTKi | Phase 2 |

NCT00543049

NCT00768144 NCT00453310 |

| AZD9150, a STAT3 Antisense Oligonucleotide | STAT3 | Phase 2 | NCT02417753 |

| Ruxolitinib Phosphate, Paclitaxel, and Carboplatin | JAK1/2 | Phase 1/2 | NCT02713386 |

| Tocilizumab and IFN-α2b+ Carboplatin and Caelyx or doxorubicin | IL-6R | Phase 1 | NCT01637532 |

| Siltuximab (CNTO 328) | IL-6R | Phase 2 | NCT00841191 |

| Plerixafor | CXCR4 | Phase 1 |

NCT02179970

NCT03277209 |

| PD 0360324+ cyclophosphamide | M-CSF | Phase 2 | NCT02948101 |

| Celecoxib + cyclophosphamide | COX-1 and COX-2 | Phase 2 | NCT00538031 |

| Ketorolac | COX-1 and COX-2/GTPase inhibition | Phase 0 | NCT02470299 |

| INCAGN01876 + Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | TNFα, PD-1 and CTLA-4. | Phase 1/2 | NCT03126110 |

| MK-3475 (pembrolizumab) + Gemcitabine and cisplatin | PD-1 | Phase 2 | NCT02608684 |

| Oregovomab and Nivolumab | CA-125 and PD-1 | Phase 1/2 | NCT03100006 |

| Durvalumab (MEDI4736 + motolimod) + pegylated liposomal doxorubicin | PD-L1 and TLL8 | Phase1/2 | NCT02431559 |

| Autologous Monocytes + Sylatron (PegIFNα)+ Actimmune (IFNγ-1b) | Immunotherapy | Phase 1 | NCT02948426 |

| Vigil bi-shRNA furin and GMCSF (FANG) Augmented Autologous Tumor Cell Immunotherapy | TGFβ1/TGFβ2+ Immune stimulation | Phase 2 | NCT02346747 |

| Vigil (Adjuvant FANG) | TGFβ1/TGFβ2 + Immune stimulation |

Phase 2 | NCT01309230 |

| Atezolizumab and Vigil | PDL1 and TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 | Phase 2 | NCT03073525 |

| Dalantercept | ALK1 (Activin, TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 receptor) | Phase 2 | NCT01720173 |

| NK immunotherapy | Combination of Cryosurgery and NK Immunotherapy | Phase 2 | NCT02849353 |

| Therapeutic autologous Antigen-specific CD4+ lymphocytes | Immunotherapy | Phase 1 | NCT00101257 |

9. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs)

Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) are CD33+CD66b+ myeloid derived cells high levels of plasticity, thus can be divided into either antitumor (N1) or protumor (N2) subtypes [147, 148]. Chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 regulate neutrophil chemotaxis towards the TME in response to granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-monocyte colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL5, CXCL8, and migration inhibitory protein 1 α (MIP1α) [149, 150].

Several studies showed that during early stages of tumor progression, neutrophils were an anti-tumorigenic, while during aggressive stages of tumor development, neutrophils tended to curtail adaptive anti-tumor immunity and assume a more pro-tumorigenic role depending on microenvironmental cues [148, 151]. For example, TGF-β favored neutrophil polarization towards an N1 phenotype [147, 152]. Phenotypically N1 PMNs have upregulated NADPH oxidase activity, leading to increased ROS, causing cancer cell death [153]. Such PMNs can also indirectly increase CD8+ T cell recruitment through CXCL9 and CXCL10, leading to an immune onslaught against tumor cells [154]. In contrast, N2 PMNs enhance tumor cell survival and metastasis, not only by repressing CD8+ T-lymphocyte and NK antitumor activities [155], but also by secreting enzymes, which remodel ECM and promote angiogenesis [42]. In support of this, co-culture of SKOV3 cells with either PMNs or their lysates led to a more pro-migratory SKOV3 phenotype. Furthermore, in biopsies from HGSC patients, PMN and ZEB1-positive cancer cells clustered predominantly in regions depleted of E-cadherin [156]. Comprehensive meta-analysis of patients’ specimens demonstrated that an increased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) correlated with platinum resistance and poorer patient survival [157]. Similarly, a retrospective study by Miao et al., reported that patients with lower neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) or platelet/lymphocyte ratio (PLR) exhibited a longer progression-free survival and overall survival, suggesting that the prognostic utility of NLR and PLR in predicting platinum resistance and overall survival [158].

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)

MDSCs are cells of myeloid origin that exist in a steady immature state and contribute to immunosuppression in the OvCa TME. Immature myeloid cells consist of CD33+ dendritic cell, macrophage, and granulocyte precursors that can be divided into monocytic or granulocytic origins [159]. While MDSCs originate in the bone marrow and continue to differentiate into mature cellular types leading to immunosuppression. Cells of monocytic origin, also called agranulocytes include macrophages, while those of granulocytic origin are characterized by the presence of granules in their cytoplasm and include polymorphonuclear leukocytes [160]. Chemokine receptor CXCR4, and prostaglandins E2 (PGE2), are involved in recruiting MDSCs to the ascitic fluid rich peritoneum [52, 53, 161–163]. COX2/PGE2 signaling contributes to the activation of immunosuppressive molecules such as indoleamine dioxygenases (IDO), arginase-1 (ARG-1), IL-10, and nitric oxide synthase-2 (NOS-2) that suppress various T-cell functions [52, 162, 164, 165]. Consistently, depletion of MDSCs by anti-granulocyte receptor (anti-GR1) increased the survival of ID8 tumor-bearing mice. Additionally, MDSCs activated by ID8- conditioned medium or ascites of ID8 tumor-bearing mice demonstrated T-cell suppressive behavior in vitro [166].

Clinical data of recurrent or advanced stage OvCa patients treated with platinum-based agents revealed that tumor G-CSF expression was significantly linked to enhanced MDSC activity, contributed to platinum resistance and decreased overall survival [167, 168]. Depletion of MDSC re-sensitized resistant tumor cells to cisplatin. Hence, the combination of MDSC-inhibiting agents with platinum agents may serve as important strategy to treat G-CSF-producing OvCa [167].

10. Natural killer (NK) cells

Natural killer cells (NK) are highly cytolytic lymphocytes of the innate immune system which express CD56 and CD16 and mainly utilize perforins and granzymes to penetrate the membranes of target cells causing an apoptotic cascade [169]. The involvement of NK cells in OvCa is multifaceted as they can exert pro-tumor or anti-tumor effects [170–172]. NK cells have been shown to destroy OvCa directly through the activation of CD16, NKG2D, and NKp30 cytotoxicity receptors, thus reducing metastasis with better overall survival. NK cells exert anti-tumorigenic effects by indirectly augmenting the efficacy of antitumor T cell and dendritic cell responses through the release of CCL3 and CCL4 [173]. In tumors co-infiltrated with NK and cytotoxic T cells, NK cells strongly correlated with improved patient survival [171]. However, in the OvCa peritoneal milieu, a plethora of immunosuppressive factors that inhibit NK cells are secreted factors from the growing tumor, TAMs, myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC) and Treg myeloid cells in the tumors and ascitic fluid [174]. For example, experimental models showed that macrophages overexpressing MIF in OvCa and ascitic fluid downregulate transcription of the NK activating receptor NKG2D and increases expression of the inhibitory checkpoint, B7-H6; both are associated with poor prognosis in OvCa [173, 175]. Similarly, TGF-β overexpression suppresses CD16-triggered NK cell IFN-γ production, downregulates the activating receptors 2B4, CD16, activating natural killer receptor p30 (NKp30), DNAX accessory molecule-1 (DNAM1), andupregulates the inhibitory checkpoint receptor programmed death-1 (PD-1) [174]. In addition to cytokine mediated suppression, CA-125, an antigen overexpressed in 80% of OvCa is secreted in ascitic fluid andcan directly protect tumor cells from NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity irrespective of their receptor repertoire [176]. Of note, while NK cells serve an essential role as anti-neoplastic and immunosurveillance cells, a subset of NK cells has been shown to propagate the neovascularization of tumorous tissue [177, 178]. These NK cells function in a manner resembling NK cells homing in the uterine wall or decidua. It has been found that NK cells in the decidua obtain a CD56brightCD16- phenotype allowing for increased release of pro-angiogenic cytokines including VEGF, PlGF, and CXCL8 (summarized in [179]). While some studies shown that this pro-angiogenic subtype of NK cells could be found in other solid tumors and malignant pleural effusions [180, 181], their presence and impact in OvCa is still unknown.

Cisplatin-resistant OvCa cells were more resistant to NK cell cytotoxicity with significant overexpression of programmed death protein ligand 1 (PD-L1) compared to their parental cells [73, 182]. Paradoxically, the expression of PD-1 in NK cells was induced after co-culture with cisplatin-resistant OvCa cells. Neutralizing antibodies to PD-1 or PD-L1 increased sensitivity of cisplatin-resistant cells to NK cell cytotoxicity and increased the sensitivity of cisplatin-resistant cells to NK cell cytotoxicity [182]. Interestingly, oxaliplatin, but not cisplatin treatment, sensitized OvCa cells to NK cell-mediated cytolysis through dual effect activating NK cells and increasing pro-apoptotic and cell death response in OvCa cells, suggesting an advantage in combining oxaliplatin and NK cell-based therapy for the treatment of platinum resistant OvCa cells [183].

11. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)

TILs include two main classes: T-cells and regulatory T cells (T-regs). TILs leave the intravascular compartment and localize inside either tumor stroma (stromal TILs) or tumor cell islets (intraepithelial TILs). Intraepithelial TILs are important in regulating nearly all solid tumors’ growth, including OvCa (summarized in [184]). As antigen presenting DCs process tumor antigens, antigens come to the attention of intraepithelial TILs via T cell receptor (TCR)-mediated recognition [184]. CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes inhibit cancer development by recognizing antigens, either upregulated expression of self-antigens or cancer-associated antigens [184]. When activated CD8+ cytotoxic T cells recognize tumor antigens by TCR/MHC engagement, they can abolish malignant cells directly via methods that include FasL/Fas binding and perforin/granzyme secretion. Cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells, along with CD4+ helper T cells, can also secrete chemokines/cytokines that marshal the forces of additional immune cells (summarized in [185]). The tumors of OvCa patients can be histologically categorized as inflamed/hot, non-inflamed/cold, and immune-excluded [186]. Hot tumors are characterized by a high density of intraepithelial CD8+ TILs [187], and such patients may be responsive to immunotherapies acting on T cell checkpoints. Cold tumors are characterized by the absence of intraepithelial TILs, and for these patients, T cell priming fails, necessitating therapies that instead distribute autologous/allogenic effector cells into tumors [186]. Immune-excluded tumors are characterized by the presence of inhibitory cells such as Tregs, MDSCs, and/or TAMs in the TME that retain stromal CD8+ TILs and prevent them from entering the tumor islets [186]. Strategies such as radiation therapy, TME remodeling molecules, epigenetic modulators, and T cell trafficking modulators can benefit these patients, where the strategy is to increase the immune effector cell infiltration of tumors [186]. Patient survival has been positively correlated with the presence of intra-epithelial TILs in clinical studies of OvCa, with survival being more persistently and substantially associated with intraepithelial CD8+ TILs versus CD3+ TILs [188–191].

Wang and colleagues reported that platinum-induced DNA damage activated costimulatory signaling pathways leading to CTL-dependent tumor death [192]. Effector CD8+ T cells T-cell-derived IFNγ altered glutathione and cystine metabolism in CAFs, decreasing CAF-secreted glutathione through upregulation of glutamyl-transferases while transcriptionally repressing cystine and glutamate antiporters and increasing nuclear accumulation of platinum in OvCa cells. Hence, the presence of stromal CAFs and CD8+ T cells is negatively and positively associated with OvCa patient survival, respectively [192]. In accord with this, Beyranvand et al., reported that platinum augments tumor cell death after CD80/86-mediated CTLs activation [193]. Intriguingly, in OvCa patients, while carboplatin did not affect CD8+ T-cell circulating populations, it increased their capacity to produce IFNγ [194].

12. Regulatory T cells (Tregs)

Activated T-cells can be suppressed in function by Tregs, a subset of CD4+ T-cells. Tregs can be split into inherent Tregs which are intrinsically generated by the thymus with a phenotype of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ and Tregs that are adaptive and have variable CD25 expression, such as Th1 and Th3 Tregs. OvCa patients express subtypes of Tregs with downregulated CD28 expression and upregulated cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) expression [195]. Interestingly, it was found that OvCa patients’ peripheral blood has elevated Treg numbers due to the presence of tumors. Furthermore, tumors demonstrated the ability to recruit and stimulate Treg tumor infiltration and localization [195].

The mechanism involved in T cell mediated cell death involves several key steps including: 1) TCR/MHC engagement, 2) activation of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells 3) perforin/granzyme secretion as well as activation of death Fas ligand (FasL/CD95L) [196]. Due to the complex interactions contributing to the inflammatory OvCa TME, the function of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is diminished by TAMs, Tregs, and MDSCs and is highly impacted by several soluble inhibitory factors including adenosine, arginase (Arg)1, IDO-1, IL-6, IL-10, and TGFβ activity [197, 198]. T cell functions are regulated via MHC molecule downregulation, as well as that of co-stimulatory ligands. T cell functions are also regulated via upregulation of inhibitory receptors, including cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4, CD152) and programmed cell death protein ligand 1 (PD-L1) on tumor cells [199]. Poor patient survival correlated better with elevated programmed death 1 (PD-1/CD279) expression on OvCa cells than with decreased levels of CD8+ TILs, implying that the expression of PD-L1 inhibits T-cell infiltration and fosters an immunosuppressive TME [200]. In further support of these findings, standard of care therapy had a synergistic effect with CTLA-4 and/or single or dual blockade of PD-1 in several OvCa models [189, 199, 201].

Several meta-analysis studies have assessed the role of key players in the OvCa peritoneal TME, namely TAMs, TILs and PMNs on OvCa patient survival outcomes. For example, nine studies encompassing 794 patients indicated that an elevated M1/M2 ratio in cancerous tissue was linked with better overall survival (OS) (HR=0.449, 95% CI=0.283–0.712, p=0.001). Moreover, higher intra-islet M1/M2 TAMs ratio correlated positively with OS (HR=0.510, 95% CI=0.264–0.986, p=0.045), while there was no relation between OS and CD68+ TAMs (HR=0.99, 95% CI=0.88–1.11, p=0.859), CD163+ TAMs (HR=1.04, 95% CI=0.92–1.16, p=0.544) or the ratio of CD163+/CD68+ TAMs (HR=1.628, 95% CI=0.529–5.008, p=0.395). Interestingly, the same study demonstrated that lower progression-free survival (PFS) was linked with an increase in CD163+ TAMs (HR=2.157, 95% CI=1.406–3.312, p=0.000) and a heightened CD163+/CD68+ TAMs ratio (HR=3.223, 95% CI=1.805–5.755, p=0.000). Moreover, a greater M1/M2 TAMs ratio correlated with higher PFS (HR=0.490, 95% CI=0.270–0.890, p=0.019). Hence, it was shown that an increase in CD163+ TAMs correlated with poorer prognosis in OvCa patients, while high M1/M2 ratio in cancerous tissue correlated with a better patient outcome [202]. With regards to neutrophils, analysis of 12 studies including 4046 patients demonstrated that a lowered neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio strongly associated with better patient outcome (hazard ratio = 1.409, 95% confidence intervals =1.112–1.786, p= 0.005) and progression-free survival (hazard ratio = 1.523, 95% CI = 1.187–1.955, p= 0.001) [203]. Furthermore, the influence of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, or TILs was evaluated in ten studies including a total of 1815 patients and showed that a decrease in intraepithelial TILs strongly associated with a poorer prognosis in OvCa patients (pooled HR: 2.24, 95% CI=1.71–2.91) [204]. Therefore, components of the TME can be used as predictors of overall survival and progression-free survival for patients with OvCa.

13. Ascitic Fluid

Malignant ascites, caused by exudation of tumor microvascular fluid and lymphatic fluid, and characterized by the abnormal accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity, is an important component of OvCa progression [51, 205]. More than one third of OvCa patients present with ascites at diagnosis, and its presence significantly correlates with both peritoneal dissemination and poor prognosis [205]. The accumulation of ascitic fluid is mainly due to overexpression and increased secretion of VEGF not only from tumor cells but also from the cancer associated mesothelial cells, macrophages, adipocytes, fibroblasts and endothelial cells that acquire pro-inflammatory, secretory cancer associated phenotype instigated by tumor cells. VEGF, initially described as vascular permeability factor [206, 207], stimulates vascular permeability through disruption of endothelial cell-cell junctions and induce hyperpermeability and degradation of endothelial membrane with leakage of macromolecules from the intravascular compartment to the peritoneal space. VEGF along with other angiogenic factors including basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), angiogenin, transforming growth factors (TGFα and β), IL-6 and IL-8 stimulate endothelial cell proliferation and migration in the peritoneal TME leading to neovascularization and angiogenesis [208–210].

Malignant ascites contains a complex amalgamation of players, including immune cells, stromal cells and CAFs, mesothelial and epithelial cells and detached tumor cells. Noncellular components also make up malignant ascites, containing growth factors, proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, bioactive lipids, small molecular metabolites, peptide hormones, cell-free DNAs, RNAs, exosomes, micro-vesicles as well as ECM proteins and proteinases. Indeed, all these components of malignant ascites confer platinum-resistance in HGSC [40, 205, 211–216].

The proinflammatory, growth factor rich TME in the ascitic fluid upregulates integrins, cell adhesion and ECM molecules in OvCa cells; these lead to the survival of OvCa cells as single and multicellular spheroids floating in the ascitic fluid and on the other hand, stimulate OvCa adhesion and invasion of the mesothelium and sub-mesothelial adipose tissues[9, 11, 69, 217–219]. Ascitic fluid OvCa spheroids express low levels of E-cadherin, but express epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) and cytokeratin and exhibit adhesive invasive and chemo-resistant phenotypes. They also exhibit traits of cancer stem cells (CSC) with respect to chemoresistance and self-renewal abilities. These cells also express genes responsible for tumorigenesis and metastasis as bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 4 (BMP-2 and 4), TGF-β, EGFR, and integrin α2 β1 [220–222]

In addition to OvCa cells, ascitic fluid also contains TAMs, MDSCs NK, and T-lymphocytes in significantly higher concentrations than matching blood samples from the same patients [223, 224]. However, pro-inflammatory factors and metabolites support the immune-suppressive functions Tregs and MDSCs and further inhibit the functions of dendritic cells, NK, CD4+ and cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells cells, thus protecting OvCa cells from immune surveillance and hence are associated with platinum-resistance [223–225]. Profiling ascites of platinum-resistant HGSC patients, Gong and colleagues [226, 227] reported that reduced numbers of CD3+/CD56+ NK or NK-like T cells significantly correlated with increased platinum resistance further implying that lack of NK cells impairs the immune surveillance in TME of malignant ascites, and hence impairs cancer cell detection, recognition and killing.

Noncellular components of the ascitic fluid include a plethora of proteins, cytokines and chemokines that are mainly mitogenic, angiogenic and pro-inflammatory as VEGF, bFGF, EGF, TGFα, TGFβ, angiogenin and angiopoietin-2, GRO (chemokine ligand 1), cell surface glycoprotein ICAM-1 (CD53), interleukins IL-6, IL-6R, IL-8, IL-10, leptin, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1/CCL2), macrophage migration inhibition factor (MIF), nucleosome assembly protein 2 (NAP-2), osteprotegerin (OPG), RANTES (CCL5), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 2 (TIMP-2) and urokinase receptor (UPAR) [228, 229]. These proteins confer vascular permeability, alterations in patient hemodynamics, and promote higher levels of tumor growth factors – altogether, these players promote HGSC growth, survival, metastasis and significantly correlated with platinum-resistance and shorter progression free survival (PFS). In addition, these factors maintain an immunosuppressive TME impeding the function of dendritic, NK and cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, and thus impairing opportunities for immune-therapy [228, 229]. In addition, CD95 ligand (aka Fas ligand) has been shown to be constitutively released by ascites-derived OvCa cells. For OvCa patients containing elevated levels of IL-1, this resulting induction of apoptosis in immune cells expressing CD95 ascites was correlated with increased overall survival [223, 224].

Clinical studies implicated the importance of IL-6 and its interactions with other cytokines in promoting platinum resistance in HGSC patients. Retrospective analysis of 70 HGSC patients who received platinum-based chemotherapy showed ascites with high levels of both IL-6 and TNF-α [230]. Stratification of patients by high TNF-α and high IL-6 levels identified a specific subgroup of patients with shorter PFS and high risk for rapid disease relapse suggesting the prognostic utility of IL-6 and TNF-α as predictive biomarkers of platinum-resistance [231]. IL-6 and cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 2 (cIAP-2) mRNA and protein levels significantly increased in the ascites of HGSC patients treated with platinum chemotherapy [232]. In vitro studies showed that blocking IL-6 and or cIAP-2 re-sensitized OvCa cells to cisplatin [232]. Ascites derived from platinum-resistant HGSC was rich in oxidative stress markers such as 8-isoprostanes as well as inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 [233]. The total antioxidant capacity (TAC) in ascites was higher in platinum-resistance patients than plasma suggesting local production by the TME impeded sensitivity to platinum chemotherapy [233].

14. Targeting the TME:

Multiple approaches have been designed to target the OvCa TME. One of the first FDA-approved approaches is targeting anti-VEGFRs by bevacizumab as a standard of care in advanced HGSC (https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-bevacizumab-combination-chemotherapy-ovarian-cancer). Another approach is targeting VEGF itself through interfering with VEGF binding to its receptors (VEGF trap Aflibercept) that is currently in clinical trials (Table 2). Other approaches currently in clinical trials aim at targeting the amplified, hyperactivated receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) either targeting a specific receptor by a specific inhibitor like bevacizumab, or multi-target RTK inhibitor as single agents or in combination with standard of care platinum or taxanes (Table 2).

Monoclonal antibodies, which can target key cytokines or chemokines have also been important tools for OvCa treatment. For example, IL-6 is highly enriched in the malignant OvCa ascitic fluid and has been shown to upregulate the invasive properties of OvCa cells [195]. The increased levels of IL-6 likely drive the IL-6R/STAT3/miR-204 feedback loop leading to cisplatin resistance of OvCa [227]. Hence, targeting IL-6 or IL6R with neutralizing antibodies may increase sensitivity of OvCa cells to cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity (Table 2). Immunotherapy with specific antibodies targeting cytokines and receptors as CXCR4, M-CSF and TNFα are also in clinical trials (Table 2). Targeting inflammation with COX inhibitors or JAK/STAT neutralizing antibodies or antisense oligonucleotides that are both upstream/downstream of cytokine/chemokine signaling that are implicated in resistance and immunosuppression that significantly contribute to the poor outcome of OvCa.

Several arms of immunotherapy were also able to reverse platinum resistance or re-sensitize OvCa cells to platinum-based drugs [234]. One arm is Adoptive Cell Therapy (ACT) which involves three fundamental steps: 1) isolation of patient’s T cells from a tumor or peripheral blood, 2) expansion of T cells ex vivo, hindered from the effects of the immunosuppressive TME, and 3) reintroduction of T cells into the patient along with recombinant IL-2 (rIL-2) after chemotherapy [235]. This process is designed to augment antitumoral activity of autologous lymphocytes [235].

Another promising arm of immunotherapy in OvCa is the use of chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), in which receptor proteins that have been engineered to provide immune cells with the ability to target a specific protein on targeted tumor cells [236, 237]. While CAR therapy has been typically discussed in the context of T cells, they can also be extended to NK or dendritic cells. One study demonstrated that cisplatin treatment along with NK92 cells, virally transduced with a third-generation anti-CD133-CAR, produced a powerful anti-tumorigenic effect against OCSCs [238].

15. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and platinum-resistance

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as anti-PD-1 and anti-PDL1- are currently in trials to reduce Treg infiltration and stimulate the generation of CD8+ TILs [239, 240]. Oxaliplatin treatment was shown to sensitize OvCa cells to NK cell-induced cytolysis by producing type I IFN and chemokines. This event led to an upregulation of the expression of MHC class I-related chains A/B, UL16-binding protein (ULBP)-3, CD155, and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-R1/R2 [73]. Additionally, anti-VEGF treatment suppressed PD-L1 expression and EMT by suppressing the phosphorylation of STAT3 in cisplatin resistant OvCa cells, and thus, led to the inhibition of OvCa progression. In particular, anti-VEGF and anti-PD-L1 agents acted synergistically to reduce in vivo OvCa growth which may be attributed to the increased immunotherapy efficacy by the anti-EMT effect of the anti-VEGF treatment [241]. NK cells derived from ascitic fluid from OvCa patients also express high levels of PD-1, and hence, allow for the use of anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies to harness the cytotoxic potential of NK cells against OvCa cells [242]. Unfortunately, in OvCa, defects in NK-cell structure, such as mutated receptor or ligand expression, can serve as methods of immune escape [38].

Finally, the link between TGF-β signaling and OvCa progression, cisplatin resistance and poor survival is multifaceted. TGF-β not only promotes tumor growth, invasiveness and dissemination but it plays a substantial role in immunosuppression through inhibition of the functions of NK cells, CD+ and CD8+ lymphocytes and augments the functions of CAFs, MDSCs, and Tregs (summarized in [243]). Thus, multiple therapies aimed at inhibiting TGF-β signaling and its impact on the TME are underway either targeting TGF-β itself and/or its receptors in combinatorial therapy with standard of care platinum or immune modulators and immune-therapeutics (Table 2).

16. Conclusion:

Targeting the TME can achieve significant anti-tumor responses to standard of care cisplatin in OvCa and improve disease outcome. Several studies and clinical trials are underway to improve the effectiveness of different combinatorial regiments with platinumtherapeutics for advanced recurrent or refractory OvCa.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, and Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin, 2020. 70(1): p. 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid BM, Permuth JB, and Sellers TA, Epidemiology of ovarian cancer: a review. Cancer Biol Med, 2017. 14(1): p. 9–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Della Pepa C, et al. , Ovarian cancer standard of care: are there real alternatives? Chin J Cancer, 2015. 34(1): p. 17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goff BA, Advanced ovarian cancer: what should be the standard of care? J Gynecol Oncol, 2013. 24(1): p. 83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.da Costa A and Baiocchi G, Genomic profiling of platinum-resistant ovarian cancer: The road into druggable targets. Semin Cancer Biol, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pokhriyal R, et al. , Chemotherapy Resistance in Advanced Ovarian Cancer Patients. Biomark Cancer, 2019. 11: p. 1179299X19860815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis A, Tinker AV, and Friedlander M, “Platinum resistant” ovarian cancer: what is it, who to treat and how to measure benefit? Gynecol Oncol, 2014. 133(3): p. 624–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slaughter K, et al. , Primary and acquired platinum-resistance among women with high grade serous ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol, 2016. 142(2): p. 225–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenny HA, et al. , Mesothelial cells promote early ovarian cancer metastasis through fibronectin secretion. J Clin Invest, 2014. 124(10): p. 4614–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenny HA, et al. , The initial steps of ovarian cancer cell metastasis are mediated by MMP-2 cleavage of vitronectin and fibronectin. J Clin Invest, 2008. 118(4): p. 1367–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lengyel E, Ovarian cancer development and metastasis. Am J Pathol, 2010. 177(3): p. 1053–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Binju M, et al. , Mechanisms underlying acquired platinum resistance in high grade serous ovarian cancer - a mini review. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj, 2019. 1863(2): p. 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMullen M, Madariaga A, and Lheureux S, New approaches for targeting platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Semin Cancer Biol, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galluzzi L, et al. , Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance. Oncogene, 2012. 31(15): p. 1869–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Page C, et al. , Lessons learned from understanding chemotherapy resistance in epithelial tubo-ovarian carcinoma from BRCA1and BRCA2mutation carriers. Semin Cancer Biol, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agarwal R and Kaye SB, Ovarian cancer: strategies for overcoming resistance to chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer, 2003. 3(7): p. 502–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin Y, et al. , Increasing sensitivity to DNA damage is a potential driver for human ovarian cancer. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(31): p. 49710–49721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amable L, Cisplatin resistance and opportunities for precision medicine. Pharmacol Res, 2016. 106: p. 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen F, et al. , New horizons in tumor microenvironment biology: challenges and opportunities. BMC Med, 2015. 13: p. 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen SJ, et al. , Desferal regulates hCtr1 and transferrin receptor expression through Sp1 and exhibits synergistic cytotoxicity with platinum drugs in oxaliplatin-resistant human cervical cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(31): p. 49310–49321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai YH, et al. , Modulating Chemosensitivity of Tumors to Platinum-Based Antitumor Drugs by Transcriptional Regulation of Copper Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci, 2018. 19(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohrvik H, et al. , Cathepsin Protease Controls Copper and Cisplatin Accumulation via Cleavage of the Ctr1 Metal-binding Ectodomain. J Biol Chem, 2016. 291(27): p. 13905–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YY, et al. , Prognostic value of the copper transporters, CTR1 and CTR2, in patients with ovarian carcinoma receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol, 2011. 122(2): p. 361–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida H, et al. , Association of copper transporter expression with platinum resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res, 2013. 33(4): p. 1409–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang T, et al. , Expression of the copper transporters hCtr1, ATP7A and ATP7B is associated with the response to chemotherapy and survival time in patients with resected non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett, 2015. 10(4): p. 2584–2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samimi G, et al. , Increase in expression of the copper transporter ATP7A during platinum drug-based treatment is associated with poor survival in ovarian cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res, 2003. 9(16 Pt 1): p. 5853–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyashita H, et al. , Expression of copper-transporting P-type adenosine triphosphatase (ATP7B) as a chemoresistance marker in human oral squamous cell carcinoma treated with cisplatin. Oral Oncol, 2003. 39(2): p. 157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higashimoto M, et al. , Expression of copper-transporting P-type adenosine triphosphatase in human esophageal carcinoma. Int J Mol Med, 2003. 11(3): p. 337–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakayama K, et al. , Prognostic value of the Cu-transporting ATPase in ovarian carcinoma patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res, 2004. 10(8): p. 2804–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petruzzelli R and Polishchuk RS, Activity and Trafficking of Copper-Transporting ATPases in Tumor Development and Defense against Platinum-Based Drugs. Cells, 2019. 8(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samimi G, et al. , Modulation of the cellular pharmacology of cisplatin and its analogs by the copper exporters ATP7A and ATP7B. Mol Pharmacol, 2004. 66(1): p. 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mangala LS, et al. , Therapeutic Targeting of ATP7B in Ovarian Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res, 2009. 15(11): p. 3770–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou J, et al. , The Drug-Resistance Mechanisms of Five Platinum-Based Antitumor Agents. Front Pharmacol, 2020. 11: p. 343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basu A and Krishnamurthy S, Cellular responses to Cisplatin-induced DNA damage. J Nucleic Acids, 2010. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dasari S and Tchounwou PB, Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol, 2014. 740: p. 364–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelland L, The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer, 2007. 7(8): p. 573–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li M, et al. , Integrated analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression reveals specific signaling pathways associated with platinum resistance in ovarian cancer. BMC Med Genomics, 2009. 2: p. 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Worzfeld T, et al. , The Unique Molecular and Cellular Microenvironment of Ovarian Cancer. Front Oncol, 2017. 7: p. 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeung T-L, et al. , Cellular and molecular processes in ovarian cancer metastasis. A Review in the Theme: Cell and Molecular Processes in Cancer Metastasis. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology, 2015. 309(7): p. C444–C456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thibault B, et al. , Ovarian cancer microenvironment: implications for cancer dissemination and chemoresistance acquisition. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2014. 33(1): p. 17–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N., Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature, 2011. 474(7353): p. 609–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang H, et al. , Integrated Proteogenomic Characterization of Human High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cell, 2016. 166(3): p. 755–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helleman J, et al. , Molecular profiling of platinum resistant ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer, 2006. 118(8): p. 1963–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patch AM, et al. , Corrigendum: Whole-genome characterization of chemoresistant ovarian cancer. Nature, 2015. 527(7578): p. 398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salaroglio IC, et al. , ERK is a Pivotal Player of Chemo-Immune-Resistance in Cancer. International journal of molecular sciences, 2019. 20(10): p. 2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seguin L, et al. , Integrins and cancer: regulators of cancer stemness, metastasis, and drug resistance. Trends in cell biology, 2015. 25(4): p. 234–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Do HTT, Lee CH, and Cho J, Chemokines and their Receptors: Multifaceted Roles in Cancer Progression and Potential Value as Cancer Prognostic Markers. Cancers, 2020. 12(2): p. 287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baudhuin LM, et al. , Akt activation induced by lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine-1-phosphate requires both mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and is cell-line specific. Mol Pharmacol, 2002. 62(3): p. 660–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lizalek J, et al. , Lysophosphatidic Acid Stimulates Urokinase Receptor (uPAR/CD87) in Ovarian Epithelial Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res, 2015. 35(10): p. 5263–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ray U, Roy SS, and Chowdhury SR, Lysophosphatidic Acid Promotes Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Ovarian Cancer Cells by Repressing SIRT1. Cell Physiol Biochem, 2017. 41(2): p. 795–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ren J, et al. , Lysophosphatidic acid is constitutively produced by human peritoneal mesothelial cells and enhances adhesion, migration, and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res, 2006. 66(6): p. 3006–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Obermajer N, et al. , Positive feedback between PGE2 and COX2 redirects the differentiation of human dendritic cells toward stable myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Blood, 2011. 118(20): p. 5498–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Obermajer N, et al. , PGE(2)-induced CXCL12 production and CXCR4 expression controls the accumulation of human MDSCs in ovarian cancer environment. Cancer Res, 2011. 71(24): p. 7463–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Said N, et al. , Normalization of the ovarian cancer microenvironment by SPARC. Mol Cancer Res, 2007. 5(10): p. 1015–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Said NA, et al. , SPARC ameliorates ovarian cancer-associated inflammation. Neoplasia, 2008. 10(10): p. 1092–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Q, et al. , The Role of Endocrine G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Ovarian Cancer Progression. Frontiers in endocrinology, 2017. 8: p. 66–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosano L, et al. , Acquisition of chemoresistance and EMT phenotype is linked with activation of the endothelin A receptor pathway in ovarian carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res, 2011. 17(8): p. 2350–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosano L and Bagnato A, Disrupting the endothelin and Wnt relationship to overcome chemoresistance. Mol Cell Oncol, 2015. 2(3): p. e995025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ino K, et al. , Role of the Renin-Angiotensin System in Gynecologic Cancers. Current Cancer Drug Targets, 2011. 11(4): p. 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cattaneo F, et al. , Cell-surface receptors transactivation mediated by g protein-coupled receptors. International journal of molecular sciences, 2014. 15(11): p. 19700–19728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Helleman J, et al. , Integrated genomics of chemotherapy resistant ovarian cancer: a role for extracellular matrix, TGFbeta and regulating microRNAs. Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 2010. 42(1): p. 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jazaeri AA, et al. , Gene expression profiles associated with response to chemotherapy in epithelial ovarian cancers. Clin Cancer Res, 2005. 11(17): p. 6300–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Godwin P, et al. , Targeting nuclear factor-kappa B to overcome resistance to chemotherapy. Frontiers in oncology, 2013. 3: p. 120–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jinawath N, et al. , Oncoproteomic analysis reveals co-upregulation of RELA and STAT5 in carboplatin resistant ovarian carcinoma. PLoS One, 2010. 5(6): p. e11198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yeung TL, et al. , TGF-beta modulates ovarian cancer invasion by upregulating CAF-derived versican in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res, 2013. 73(16): p. 5016–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qiu L, et al. , Novel oncogenic and chemoresistance-inducing functions of resistin in ovarian cancer cells require miRNAs-mediated induction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 12522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gyorffy B, Lanczky A, and Szallasi Z, Implementing an online tool for genome-wide validation of survival-associated biomarkers in ovarian-cancer using microarray data from 1287 patients. Endocr Relat Cancer, 2012. 19(2): p. 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pénzváltó Z, et al. , MEK1 is associated with carboplatin resistance and is a prognostic biomarker in epithelial ovarian cancer. BMC cancer, 2014. 14: p. 837–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iwanicki MP, et al. , Ovarian cancer spheroids use myosin-generated force to clear the mesothelium. Cancer Discov, 2011. 1(2): p. 144–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lengyel E, et al. , Cancer as a Matter of Fat: The Crosstalk between Adipose Tissue and Tumors. Trends Cancer, 2018. 4(5): p. 374–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang L, et al. , Cancer-associated fibroblasts enhance metastatic potential of lung cancer cells through IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(44): p. 76116–76128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo Q, et al. , Targeted therapy clinical trials in ovarian cancer: improved outcomes by gene mutation screening. Anticancer Drugs, 2020. 31(2): p. 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Siew YY, et al. , Oxaliplatin regulates expression of stress ligands in ovarian cancer cells and modulates their susceptibility to natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Int Immunol, 2015. 27(12): p. 621–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yahaya MAF, et al. , Tumour-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) in Colon Cancer and How to Reeducate Them. J Immunol Res, 2019. 2019: p. 2368249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]