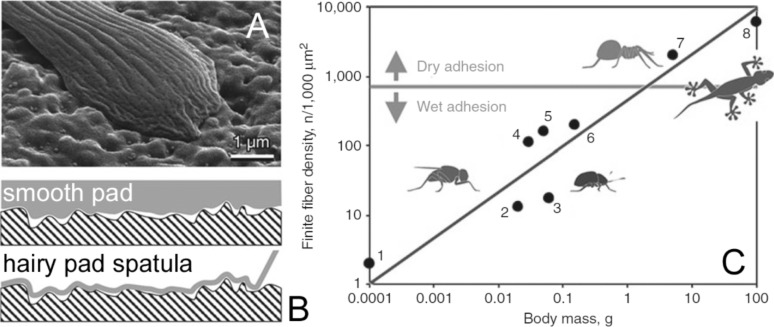

Figure 6.

Compliancy of adhesive structures to the substrate (A,B) and contact splitting (C). (A) Contact of a spatula of the beetle Gastrophysa viridula with a surface with microscale roughness. (B) Soft smooth pad requires additional load to form an adhesive contact (B, upper image), whereas the adhesion interaction pulls the elastic thin film of the spatula into a complete contact with the rough substrate surface (Figure 6A and 6B are from [241] and were adapted by permission from Springer Nature from “Biological fibrillar adhesives: functional principles and biomimetic applications. In: Handbook of Adhesion Technology” by S. N. Gorb, Copyright 2011 Springer Nature. This content is not subject to CC BY 4.0). (C) Dependence of the contact density of terminal contacts on the body mass in fibrillar pad systems in representatives of diverse animal groups: 1, 2, 4, 5, flies; 3 beetle; 6 bug; 7 spider; 8 Gekkonid lizard (Figure 6C is from [247] and was adapted by permission from Springer Nature from “Biological Micro– and Nanotribology: Nature’s Solutions” by M. Scherge and S. N. Gorb, Copyright 2001 Springer Nature. This content is not subject to CC BY 4.0). The systems, situated above the solid horizontal line, preferably rely on van der Waals forces (dry adhesion), whereas the rest rely mostly on capillary and viscous forces (wet adhesion).