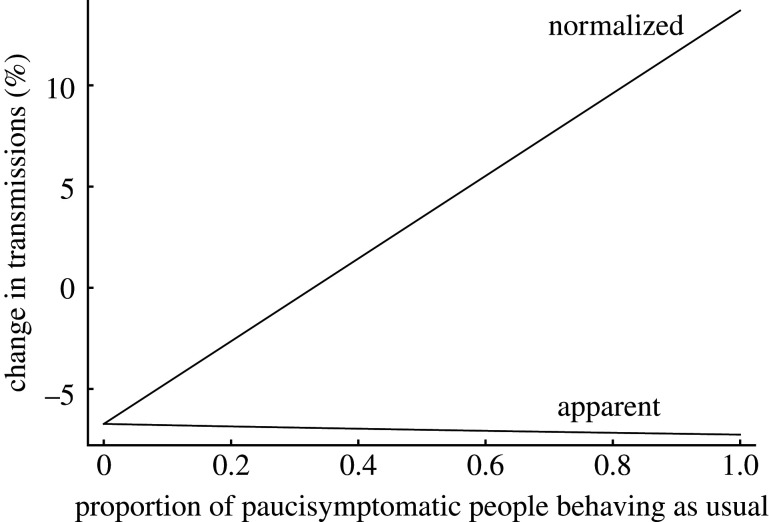

Figure 1.

Behaviour changes in people with minor symptoms may negate the effect of screening. Model output where the proportion of those developing minor symptoms (paucisymptomatic people) behaving as usual, rather than isolating, is varied from 0 to 1, with parameters otherwise as in our realistic scenario. There are two ways of viewing the effect of screening. Firstly, one can just consider the effect of screening and isolation itself, so that as fewer people isolate before being screened, there are more transmissions to interrupt and so screening appears to stop more transmissions (‘apparent’ change in transmissions line, with number of transmissions in absence of screening as denominator, showing estimated change in transmissions varying from −6.7% when all paucisymptomatic people isolate, to −7.3% when all paucisymptomatic people behave as usual). Secondly, one can consider changes in behaviour also to be part of the impact of screening: in this case, the effect is the change in transmissions caused by an increase in the proportion of paucisymptomatic people behaving as usual from a fixed proportion (which we define to be zero, i.e. all paucisymptomatic people isolating) and then screening and isolation of those not already isolating (‘normalized’ change in transmissions line, with number of transmissions in the absence of screening when all paucisymptomatic people isolate as denominator, showing estimated change in transmissions varying from −6.7% when all paucisymptomatic people continue to isolate, to +13.7% when all paucisymptomatic people behave as usual). The combined effect is at best a reduced effectiveness in screening, and at worst an increase in the number of transmissions. (Note that the figure can be redrawn with the ‘normalized’ line representing the change from a different fixed proportion of paucisymptomatic people behaving as usual prior to the introduction of screening, but that as long as screening causes the proportion to increase, the overall result will still hold.)