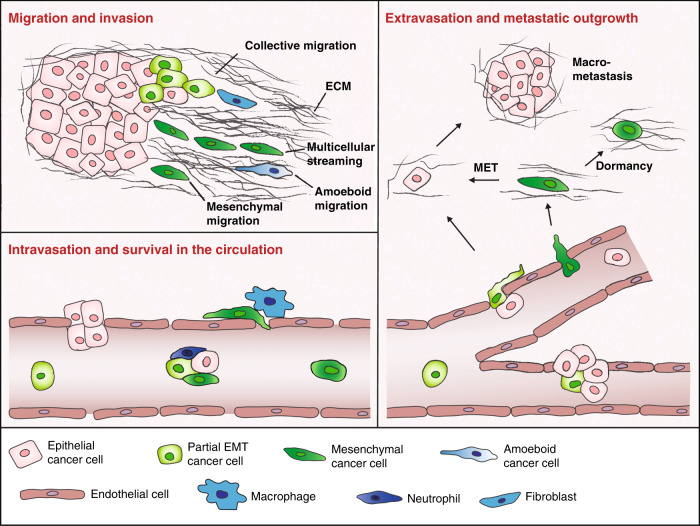

Fig. 2. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal plasticity during the metastatic process.

Cancer cells can invade the surrounding tissue as single cells by epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) followed by protease-independent amoeboid migration, or by EMT and protease-dependent mesenchymal migration. Cells in a hybrid EMT state can migrate as cohesive groups that are often led by a mesenchymal cell (a cancer cell or fibroblast), while mesenchymal cancer cells migrate as single cells or as multicellular streams. Cancer cells can actively intravasate or be passively shed into the circulation. Perivascular macrophages can aid cancer cells in the intravasation process. Circulating tumour cells (CTCs) are found in various stages of EMT as single cells or in clusters with epithelial, hybrid EMT and mesenchymal cancer cells as well as stromal cells, such as neutrophils. Successful metastatic outgrowth requires an epithelial phenotype, which most likely arises from invasive mesenchymal cancer cells undergoing mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), while tumour dormancy might be associated with a mesenchymal phenotype. Note that the molecular details of the differential regulation of the distinct modes of cancer cell migration and invasion, the intravasation process, the decision to circulate either as single cancer cell or to form CTC clusters, and CTC extravasation, tumour dormancy and metastatic outgrowth, are still widely unknown and remain to be explored.