Abstract

Background

Metformin may improve the prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma, but the existing literature is limited and contradictory.

Methods

This was a Swedish population-based cohort study of diabetes patients who were diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma in 2005–2018 and followed up until December 2019. The data were retrieved from four national health data registries: Prescribed Drug Registry, Cancer Registry, Patient Registry and Cause of Death Registry. Associations between metformin use before the gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis and the risk of disease-specific and all-cause mortality were assessed using multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression. The hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were adjusted for sex, age, calendar year, comorbidity, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or aspirin, and use of statins.

Results

Compared with non-users, metformin users had a decreased risk of disease-specific mortality (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.67–0.93) and all-cause mortality (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.68–0.90). The associations were seemingly stronger among patients of female sex (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.49–0.89), patients with tumour stage III or IV (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.58–0.88), and those with the least comorbidity (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.57–0.89).

Conclusions

Metformin use may improve survival in gastric adenocarcinoma among diabetes patients.

Subject terms: Gastric cancer, Epidemiology, Cancer epidemiology

Background

Gastric cancer is common and carries a poor overall prognosis. In 2018, gastric cancer caused nearly 800,000 deaths (1 of every 12 deaths) globally, making it the 2nd leading cause of cancer-related death.1,2 Adenocarcinoma is the dominating histological type (>95%) of gastric cancer.

Treatment strategies in gastric adenocarcinoma incorporate a multidisciplinary approach where surgical resection (gastrectomy) is the mainstay of treatments with curative intent, while patients with unresectable or metastatic disease are usually treated with chemotherapy and targeted therapy. Despite the efforts to optimise these treatments, the overall survival has not been improved much. In Sweden, the overall 5-year survival rate in gastric adenocarcinoma has been stable at around 18% during the last few decades.3 Novel treatment alternatives that can improve the survival in gastric adenocarcinoma are highly warranted. Recent studies have indicated that use of metformin, a first-line medication for diabetes, may improve the prognosis in cancer of the colon and prostate,4,5 and experimental studies have found that metformin can inhibit the proliferation of gastric cancer cells and suppress metastases.6,7 However, the few studies that have examined how metformin use influences the survival in gastric adenocarcinoma have provided inconsistent findings.8–11

We aimed to help clarify whether metformin use improves the survival in gastric adenocarcinoma among diabetes patients in a large and population-based cohort study.

Methods

Source cohort

The participants were identified from a Swedish nationwide population-based cohort, entitled the Swedish Prescribed Drugs and Health Cohort (SPREDH), which has been presented in detail elsewhere.12 In brief, SPREDH includes 9,091,193 Swedish residents who have been dispensed at least one commonly prescribed medication from 1st July 2005 to 28th February 2020. For each individual included in this cohort, relevant data were retrieved from the following four national health data registries in Sweden: Prescribed Drug Registry, Cancer Registry, Patient Registry and Cause of Death Registry, which are briefly described below. The linkages of individuals’ data between these registries were enabled by the unique personal identity number assigned to each Swedish resident upon birth or immigration.

The Prescribed Drug Registry records dispensing dates and doses of all prescribed and dispensed drugs in Sweden from 1st July 2005 onwards, except for those sold over the counter or used in hospitals. The recorded dispensed drugs account for 84% of the total drug sales in Sweden.13,14

The Cancer Registry collects information about all cancers diagnosed in Sweden from 1958 onwards. The completeness and positive predictive value of the diagnosis gastric adenocarcinoma in the Cancer Registry are 98% and 96%, respectively.15

The Cause of Death Registry contains data on dates and causes of death of all Swedish residents since 1952. The completeness of these data is over 99%.16

The Patient Registry records data on diagnoses and surgical procedures in inpatient care from 1987 onwards and all specialist outpatient care since 2001.17 The positive predictive value of in-hospital diagnoses ranges from 85 to 95%.18

Study design

The cohort of the present study consisted of patients in the SPREDH with both diabetes and gastric adenocarcinoma. The inclusion criteria were gastric adenocarcinoma, diagnosed as the primary malignancy between 1st July 2005 and 31st December 2018, and diabetes, defined by a history of use of any anti-diabetes medication before the gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis. The date and diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma were identified in the Cancer Registry, using the 7th edition of International Classification of Diseases [ICD-7] code 151, combined with the histology code 096 according to the WHO/HS/CANC/24.1 classification. The use of anti-diabetes medication was identified by the dispensed records with Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes A10A and A10B in the Prescribed Drug Registry.

Individuals were excluded if they had any cancer (except for non-melanoma skin cancer), gestational diabetes, or polycystic ovarian syndrome (another indication for metformin) diagnosed before the cohort entry, or died on the same day as the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma. Previous cancer diagnoses were retrieved from the Cancer Registry with ICD-7 codes 140-209 (excluding 191, non-melanoma skin cancer). Diagnoses of gestational diabetes and polycystic ovarian syndrome were identified in the Patient Registry by the Swedish version of ICD-10 codes O24.4 and O24.9 for gestational diabetes, and the Swedish version of ICD-9 code 256E and the Swedish version of ICD-10 code E28.2 for polycystic ovarian syndrome. Dates of death were retrieved from the Cause of Death Registry. All patients were followed up from the date of gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis until the first occurrence of death or end of the study period (31st December 2019).

Exposure

The exposure was metformin use within two years before the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma. Use of metformin was defined by the ATC codes A10BA02, A10BD02, A10BD03, A10BD05, A10BD07, A10BD08, A10BD10, A10BD11, A10BD13, A10BD14, A10BD15, A10BD16, A10BD17, A10BD18, A10BD20, or A10BD22 in the Prescribed Drug Registry.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was mortality due to gastric adenocarcinoma (disease-specific mortality), represented by gastric cancer as the main or contributing cause of death in the Cause of Death Registry and identified by the ICD-10 code C16. The secondary outcome was mortality from any cause (all-cause mortality).

Covariates

Six potential confounders were considered: sex (male or female), age at gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis (continuous), calendar year of gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis (2005–2009, 2010–2014, or 2015–2018), comorbidity (Charlson Comorbidity Index 0, 1, or ≥2, excluding gastric adenocarcinoma and diabetes), use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or aspirin (yes or no), and use of statins (yes or no). Comorbidity was defined by the well-validated Charlson Comorbidity Index which systematically accounts for the number and seriousness of certain groups of co-existing diseases.19 The diagnoses of these co-existing diseases were retrieved from the Patient Registry within 3 years before the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma. Use of NSAIDs, aspirin, and statins may reduce the mortality in cancer patients.20–22 The use of these medications was defined as at least two dispensed records within 2 years before the gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis, and was retrieved from the Prescribed Drug Registry by the relevant ATC codes (M01A, N02BA, B01AC06, C10BX01, C10BX02, C10BX04, C10BX05, C10BX06, C10BX08, C10BX12, C07FX02, C07FX03, or C07FX04 for NSAIDs or aspirin; and C10AA or C10B for statins).

Sex, age, tumour stage, gastrectomy, and anatomical sub-locations of the gastric adenocarcinoma were considered potential effect modifiers. Tumour stage data were retrieved from the Cancer Registry using the 6th edition of the Union of International Cancer Control TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, and were categorised as stage Tis to II or III to IV. Dates and procedure codes of gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma were retrieved from the Patient Registry, identified by the Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee Classification of Surgical Procedures codes JDC and JDD. Patients with the tumour sub-location in the gastric cardia were identified by the ICD-7 code 151.1 in the Cancer Registry, while all other patients were considered having gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma.

Statistical analysis

Main analyses

Survival curves were depicted using Kaplan–Meier plots comparing users with non-users of metformin. The log-rank test was used to evaluate possible differences between the curves. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for mortality outcomes comparing metformin users with non-users. Two models were applied, a crude model without any adjustment and a multivariable model with adjustment for the six potential confounders presented above.

Stratified analyses

Stratified analyses were conducted using Cox regression for both disease-specific and all-cause mortality in order to test if any association was different in subgroups of patients. The analyses were stratified by sex (male or female), age (above or below the median), anatomical tumour sub-location (non-cardia or cardia), tumour stage (Tis to II or III to IV), and gastrectomy (yes or no). In the analyses of the gastrectomy group, the person-years at risk of mortality were counted from the date of gastrectomy instead of the date of gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis.

Sensitivity analyses

The risk of disease-specific mortality was also tested using seven sensitivity analyses:

(1) A competing-risks model accounting for death due to other causes, according to the method developed by Fine and Gray;23

(2) Excluding patients who entered the cohort before 1st July 2007, because their observation period of metformin use was shorter than two years;

(3) Excluding patients with metformin monotherapy, because their diabetes might be milder compared with patients using several or other anti-diabetes drugs;24

(4) Further adjusting for insulin use (yes or no) in addition to the main multivariable model presented above, where insulin use was served as a proxy of diabetes severity. The use of insulin was defined as any dispensed record of insulin within two years before the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma as identified by the ATC code A10A in the Prescribed Drug Registry.

(5) Counting death from oesophageal cancer together with death from gastric cancer in the analysis of disease-specific mortality, because there could be misclassification of gastric and oesophageal cancer. Oesophageal cancer was identified by the ICD-10 code C15 in the Cause of Death Registry.

(6) and (7) To assess the validity of the findings for metformin, the main analyses were repeated for use of insulin (yes or no) and sulfonylurea (yes or no) in relation to the disease-specific mortality among metformin non-users. The use of insulin or sulfonylureas (ATC code A10BB) was defined as at least one dispensed record of the medication within two years before the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma.

Analyses of dosage of metformin

Analyses of dosage of metformin use in relation to the risk of disease-specific mortality were performed among metformin users diagnosed after July 1st 2007, the date that the Prescribe Drug Registry was established for 2 years. These participants were categorised into four equal-sized groups (quartiles) according to the total defined daily dose (DDD) of metformin intake within 2 years before the cancer diagnosis (<225 DDD, 225–450 DDD, 450–700 DDD, and >700 DDD). P-value for trend was computed by treating the total DDD as a continuous variable based on the median values of each category.

General

The analyses followed a pre-defined study protocol. The proportional hazard assumption for the Cox regression analyses was tested by evaluating whether the scaled Schoenfeld residuals were constant over time, and this assumption was met for all analyses. The collinearity among variables in the multivariable model was tested with calculation of uncentered variance inflation factors, and none of them were above 10.25 All analyses were performed using the statistical software Stata (Release 13, StataCorp, College Station, Texas). A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients

The study included 1140 diabetes patients who developed gastric adenocarcinoma. Among these, 777 (68.2%) were metformin users and 363 (31.8%) did not use metformin. Compared with non-users, metformin users were more often male, younger, and diagnosed in a later calendar period, and more likely to undergo gastrectomy, while they were less likely to have comorbidities and be insulin users (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1140 diabetes patients with gastric adenocarcinoma in Sweden in 2005–2018.

| All patients number (%) | Metformin users number (%) | Metformin non-users number (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1140 (100) | 777 (68.2) | 363 (31.8) |

| Person-years | 1972 (100) | 1483 (75.2) | 489 (24.8) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 807 (70.8) | 561 (72.2) | 246 (67.8) |

| Female | 333 (29.2) | 216 (27.8) | 117 (32.2) |

| Median age (interquartile range) | 73 (66–80) | 72 (65–78) | 75 (68–82) |

| Calendar year of diagnosis | |||

| 2005 (July)-2009 | 327 (28.7) | 194 (25.0) | 133 (36.6) |

| 2010–2014 | 429 (37.6) | 307 (39.5) | 122 (33.6) |

| 2015–2018 | 384 (33.7) | 276 (35.5) | 108 (29.8) |

| Tumour stage | |||

| Tis-II | 291 (25.5) | 211 (27.2) | 80 (22.0) |

| III–IV | 638 (56.0) | 450 (57.9) | 188 (51.8) |

| Unspecified | 211 (18.5) | 116 (14.9) | 95 (26.2) |

| Gastrectomy | |||

| Yes | 297 (26.1) | 221 (28.4) | 76 (20.9) |

| No | 843 (74.0) | 556 (71.6) | 287 (79.1) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||

| 0 | 667 (58.5) | 495 (63.7) | 172 (47.4) |

| 1 | 280 (24.6) | 184 (23.7) | 96 (26.4) |

| ≥2 | 193 (16.9) | 98 (12.6) | 95 (26.2) |

| Insulin use | |||

| Yes | 489 (42.9) | 248 (31.9) | 241 (66.4) |

| No | 651 (57.1) | 529 (68.1) | 122 (33.6) |

| Years of follow-up, median (interquartile range) | 0.72 (0.24–1.96) | 0.86 (0.28–2.23) | 0.46 (0.14–1.38) |

Risk of mortality

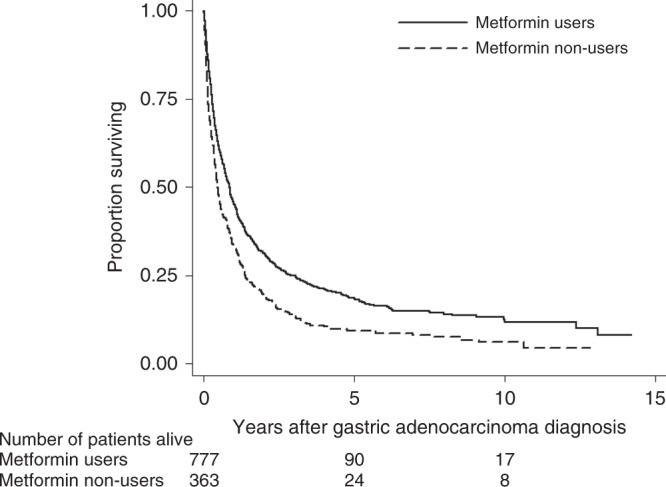

The 5-year overall survival rate was 18.3% in metformin users and 9.4% in non-users. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed better survival in metformin users than that in non-users (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with gastric adenocarcinoma and diabetes by metformin use.

P < 0.001 (log-rank test).

The main analyses showed that compared with non-users of metformin, metformin users had a decreased risk of both disease-specific mortality (adjusted HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.67–0.93) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.68–0.90) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of mortality after gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis in relation to metformin use among diabetes patients.

| Disease-specific mortality | All-cause mortality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of deaths | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | Number of deaths | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | |

| All participants | ||||||

| No metformin | 242 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 330 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 451 | 0.69 (0.59–0.81) | 0.79 (0.67–0.93) | 632 | 0.70 (0.61–0.80) | 0.78 (0.68–0.90) |

| Men | ||||||

| No metformin | 155 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 220 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00(Reference) |

| Metformin | 312 | 0.75 (0.62–0.92) | 0.85 (0.69–1.03) | 460 | 0.77 (0.66– 0.91) | 0.84 (0.71–0.99) |

| Women | ||||||

| No metformin | 87 | 1.00(Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 110 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 139 | 0.59 (0.45–0.77) | 0.66 (0.49–0.89) | 172 | 0.57 (0.45–0.72) | 0.62 (0.48–0.81) |

| Age < 73 years | ||||||

| No metformin | 80 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 116 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 218 | 0.78 (0.60–1.00) | 0.83 (0.64–1.09) | 316 | 0.76 (0.62–0.95) | 0.80 (0.64–1.00) |

| Age ≥ 73 years | ||||||

| No metformin | 162 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 214 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 233 | 0.71 (0.58–0.87) | 0.80 (0.64–0.99) | 316 | 0.72 (0.61–0.86) | 0.83 (0.69–0.99) |

| Gastric cardia adenocarcinoma | ||||||

| No metformin | 58 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 108 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 127 | 0.70 (0.51–0.96) | 0.82 (0.60–1.14) | 236 | 0.67 (0.53–0.84) | 0.75 (0.59–0.95) |

| Gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma | ||||||

| No metformin | 185 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 223 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 324 | 0.71 (0.59–0.85) | 0.79 (0.65–0.95) | 396 | 0.72 (0.61–0.85) | 0.80 (0.67–0.95) |

| Tumour stage Tis-II | ||||||

| No metformin | 37 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 59 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 78 | 0.73 (0.49–1.08) | 0.87 (0.57–1.31) | 131 | 0.76 (0.56–1.04) | 0.89 (0.64–1.23) |

| Tumour stage III–IV | ||||||

| No metformin | 141 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 181 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 303 | 0.66 (0.54– 0.80) | 0.71 (0.58–0.88) | 400 | 0.66 (0.55–0.79) | 0.71 (0.59–0.85) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index 0 | ||||||

| No metformin | 116 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 155 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 275 | 0.66 (0.53–0.82) | 0.71 (0.57–0.89) | 387 | 0.68 (0.57–0.82) | 0.70 (0.58–0.85) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index 1 | ||||||

| No metformin | 62 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 85 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 109 | 0.82 (0.60–1.12) | 0.91 (0.66–1.27) | 155 | 0.84 (0.64–1.09) | 0.90 (0.68–1.19) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥ 2 | ||||||

| No metformin | 64 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 90 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 67 | 0.78 (0.56–1.11) | 0.85 (0.59–1.22) | 90 | 0.74 (0.55–0.99) | 0.81 (0.59–1.11) |

| No gastrectomy | ||||||

| No metformin | 202 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 271 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 347 | 0.71 (0.60–0.84) | 0.82 (0.68–0.99) | 494 | 0.73 (0.63–0.85) | 0.81 (0.69–0.95) |

| Gastrectomyb | ||||||

| No metformin | 40 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 59 | 1.0 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin | 104 | 0.81 (0.56–1.16) | 0.87 (0.60–1.27) | 138 | 0.73 (0.54–0.99) | 0.79 (0.58–1.08) |

aAdjusted for sex, age, calendar year of gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or aspirin, use of statins, and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

bPatients who underwent gastrectomy were followed up from the date of surgery.

The results of the stratified analyses are shown in Table 2. The risk estimates were similar for disease-specific and all-cause mortality in most stratified analyses. The decreased risk of mortality seemed more pronounced in women (disease-specific HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.49–0.89), and in patients with more advanced tumour stage (disease-specific HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.58–0.88) and less comorbidity (disease-specific HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.57–0.89 for Charlson Comorbidity Index 0).

When applying the competing-risks model, the decreased risk of disease-specific mortality in metformin users was attenuated (adjusted sub-HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.73–1.02). The adjusted sub-HR of mortality due to other causes than gastric adenocarcinoma was 0.92 (95% CI 0.71–1.20) comparing metformin users with non-users. The cumulative mortality curves depicted by the competing-risks model showed that metformin users had a decreased risk of mortality in both gastric adenocarcinoma and other causes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Cumulative mortality curves comparing metformin-users with non-users by competting-risks model.

Cumulative disease-specific and other-cause mortality in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma and diabetes by metformin use, estimated by competing risks regression.

The results of four sensitivity analyses are shown in Table 3. The sensitivity analyses excluding patients diagnosed before 1st July 2007, excluding patients with metformin monotherapy, further adjusting for insulin use, and adjusting for potential outcome misclassification yielded similar risk estimates as those of the main analyses. Besides, use of insulin (adjusted HR 1.14, 95% CI 0.86–1.50) or sulfonylureas (adjusted HR 1.07, 95% CI 0.80–1.43) did not influence the disease-specific mortality among metformin non-users.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analyses of hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of mortality after gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis in relation to metformin use among diabetes patients.

| Disease-specific mortality | ||

|---|---|---|

| Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | |

| Excluding patients entered before 30th June 2017 | ||

| Non-users (Number of deaths = 196) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin users (Number of deaths = 394) | 0.70 (0.59–0.84) | 0.80 (0.67–0.96) |

| Excluding patients with metformin monotherapy | ||

| Non-users (Number of deaths = 186) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin users (Number of deaths = 226) | 0.69 (0.56–0.83) | 0.78 (0.64–0.96) |

| Adjusting for insulin use | ||

| Non-users | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin users | 0.69 (0.59–0.81) | 0.82 (0.69–0.97) |

| Adjusting for potential outcome misclassification | ||

| Non-users (Number of deaths = 272) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Metformin users (Number of deaths = 542) | 0.74 (0.64–0.85) | 0.82 (0.71–0.96) |

aAdjusted for sex, age, calendar year of gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or aspirin, use of statins, and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

No clear association was found between the dosage of metformin use and the risk of disease-specific mortality (Table 4).

Table 4.

Dosage of metformin and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of disease-specific mortality in gastric adenocarcinoma.

| Dosagea | Number of deaths | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| <225 DDD | 101 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 225–450 DDD | 113 | 1.06 (0.81–1.38) | 1.06 (0.81–1.39) |

| 450–700 DDD | 90 | 0.91 (0.68–1.21) | 0.93 (0.69–1.23) |

| >700 DDD | 90 | 0.91 (0.69–1.21) | 0.97 (0.72–1.29) |

| P for trend | 0.338 | 0.598 |

aDefined by total defined daily dose (DDD) used in the two years before the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma.

bAdjusted for sex, age, calendar year of gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or aspirin, use of statins, and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Discussion

This study found that diabetes patients who used metformin before the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma had a decreased risk of disease-specific and all-cause mortality compared with non-users of metformin. The associations were corroborated in several sensitivity analyses and were seemingly stronger among patients of female sex, more advanced tumour stage, and less comorbidity, while the associations were not influenced by the dosage of metformin use.

Among strengths of this study are the population-based design, large sample size, high-quality data for the exposures, outcomes and covariates, adjustment for confounders, and complete follow-up. The inclusion of only diabetes patients counteracted confounding by diabetes, as diabetes might increase the risk of mortality among patients with gastric adenocarcinoma.26 Additionally, confounding by severity and duration of diabetes was evaluated by sensitivity analyses excluding the mildest diabetes patients and adjusting for insulin use, and the unchanged associations indicated the robustness of the main findings. Lastly, the lack of influence of insulin or sulfonylurea on the prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma strengthened the validity of the results. There were also weaknesses. First, some potential confounders, e.g. socioeconomic status and lifestyle factors, were not possible to adjust for. However, these variables are not strong predictors of mortality in gastric adenocarcinoma and should thus have limited influence on the disease-specific mortality. Second, we were unable to assess the influence of some prognostic clinical variables, e.g. perioperative chemotherapy, resection margins and lymph nodes yield, because these data were not available in the registries. However, it is unlikely that these factors could influence the use of metformin before gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosis, and should thus not confound the associations. Third, despite the relatively large sample size, some of the subgroup analyses had low statistical power. Yet, the point estimates were all in the same direction, indicating consistency of the findings.

Only six previous studies have examined metformin use in relation to survival in gastric cancer.8–11 Three studies from East Asia investigating diabetes patients who underwent gastrectomy for gastric cancer showed that postoperative metformin use was associated with better survival.8,27,28 A study from Belgium including 371 patients with diabetes and gastric cancer suggested a decreased all-cause mortality, but not disease-specific mortality, associated with use of metformin.9 The other two studies, one from China of 543 patients and one from Lithuania of 555 patients, found no association between metformin use and survival in gastric cancer.10,11 The discrepancies between these results may reflect differences in study populations, exposure assessments, adjustment for confounders, or be due to chance. The present study including 1140 patients was larger than any of the previous studies.

In a Korean study, a dose-response association between cumulative metformin use and mortality of gastric cancer was suggested in general population.29 The lack of dose-response association in the present study may be due to a threshold effect of metformin, or that the 2-year exposure period was too short to reflect any linear association. Lack of dose-response association was also found in two other studies, which is consistent with our results.27,28

Several potential mechanisms could explain the survival benefit in metformin users with gastric adenocarcinoma found in the present study. First, metformin can activate AMP-activated protein kinase and regulate its downstream signalling pathways, resulting in decreased proliferation, migration and invasion, and increased apoptosis in gastric cancer cells.30 Second, metformin may influence gastric cancer stem cells, leading to inhibition of tumour growth and prevention of tumour recurrence.30 Third, metformin may indirectly affect gastric cancer cells by decreasing blood glucose and insulin levels.31 Fourth, metformin may have a synergistic effect together with chemotherapy on gastric cancer cells.32,33 The latter mechanism may explain the better survival associated with metformin use among patients with more advanced tumour stage and those who did not undergo gastrectomy, because most of these patients were likely to have received chemotherapy. The reason why women appeared to benefit more from metformin use than men is unclear, but such sex difference has been reported also in patients with colorectal cancer.34 Speculatively, sex hormonal factors may be involved.

In order to establish that metformin use improves the survival in gastric adenocarcinoma, further research is needed. Two previous studies from East Asia showed a stronger association between metformin use and prognosis of gastric cancer than that found in the present study.8,27 Whether this is due to chance or differences between populations is not clear. Besides, the present study was limited to diabetes patients, and whether the observed survival benefit of metformin use could be generalised to non-diabetes patients is unclear. A phase-II randomised controlled trial has been initiated to test the combined effect of using metformin and vitamin C on the prognosis in several cancers, including gastric cancer (https://clinicaltrials.gov). But this trial is small, and taking the limited evidence published so far and the low cost-effectiveness of randomised clinical trials into account, well-designed cohort studies from different populations seem more feasible at the present stage to investigate the possible therapeutic role of metformin in gastric adenocarcinoma.

In conclusion, this population-based and nationwide Swedish cohort study, indicates that metformin use among diabetes patients decreases the risk of disease-specific and all-cause mortality in gastric adenocarcinoma. This finding highlights the need for research examining the potential role of metformin as an adjuvant therapeutic agent against this cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All listed authors designed the study. J.L. and S.X. collected the data for the study. J.Z and G.S. analysed the data. J.Z. interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. All listed authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the article, including the authorship list. J.L. is the guarantor of this work. Both J.L. and the corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the “Declaration of Helsinki”, and was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (2018/271-32). No individual informed consent was needed according to the Swedish regulation.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Data availability

All the data were retrieved from the Swedish Prescribed Drugs and Health Cohort. The original data are available from the registries listed above, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and therefore are not publicly available. Data may however be available through applications to these registries or reasonable request to the corresponding author (S.X.). The codes for the data analysis are archived by the first author (J.Z.).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding information

This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (grant number 180684 to J.L. and 190043 to S.X.); and the Swedish Research Council (grant number 2019-00209 to J.L.). J.Z. receives a scholarship from China Scholarship Council (student number 201700260292). The founding resources were not involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation of the results; nor in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzmaurice C, Akinyemiju TF, Al Lami FH, Alam T, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Allen C, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1553–1568. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asplund J, Kauppila JH, Mattsson F, Lagergren J. Survival trends in gastric adenocarcinoma: a population-based study in sweden. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018;25:2693–2702. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6627-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joo MK, Park JJ, Chun HJ. Additional benefits of routine drugs on gastrointestinal cancer: statins, metformin, and proton pump inhibitors. Dig. Dis. 2018;36:1–14. doi: 10.1159/000480149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coyle C, Cafferty FH, Vale C, Langley RE. Metformin as an adjuvant treatment for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2016;27:2184–2195. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valaee S, Yaghoobi MM, Shamsara M. Metformin inhibits gastric cancer cells metastatic traits through suppression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in a glucose-independent manner. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0174486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu C-C, Chiang J-H, Tsai F-J, Hsu Y-M, Juan Y-N, Yang J-S, et al. Metformin triggers the intrinsic apoptotic response in human AGS gastric adenocarcinoma cells by activating AMPK and suppressing mTOR/AKT signaling. Int J. Oncol. 2019;54:1271–1281. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2019.4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee CK, Jung M, Jung I, Heo SJ, Jeong YH, An JY, et al. Cumulative metformin use and its impact on survival in gastric cancer patients after gastrectomy. Ann. Surg. 2016;263:96–102. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lacroix O, Couttenier A, Vaes E, Cardwell CR, De Schutter H, Robert A. Impact of metformin on gastric adenocarcinoma survival: A Belgian population based study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;53:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dulskas A, Patasius A, Linkeviciute-Ulinskiene D, Zabuliene L, Smailyte G. A cohort study of antihyperglycemic medication exposure and survival in patients with gastric cancer. Aging. 2019;11:7197–7205. doi: 10.18632/aging.102245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baglia ML, Cui Y, Zheng T, Yang G, Li H, You M, et al. Diabetes medication use in association with survival among patients of breast, colorectal, lung, or gastric cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2019;51:538–546. doi: 10.4143/crt.2017.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie S-H, Santoni G, Mattsson F, Ness-Jensen E, Lagergren J. Cohort profile: the Swedish Prescribed Drugs and Health Cohort (SPREDH) BMJ Open. 2019;9:e023155. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallerstedt SM, Wettermark B, Hoffmann M. The First Decade with the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register - A Systematic Review of the Output in the Scientific Literature. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016;119:464–469. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, Leimanis A, Otterblad Olausson P, Bergman U, et al. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register-opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2007;16:726–735. doi: 10.1002/pds.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekstrom AM, Signorello LB, Hansson LE, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Nyren O. Evaluating gastric cancer misclassification: a potential explanation for the rise in cardia cancer incidence. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999;91:786–790. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.9.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooke HL, Talback M, Hornblad J, Johansson LA, Ludvigsson JF, Druid H, et al. The Swedish cause of death register. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2017;32:765–773. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0316-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakobsson GL, Sternegard E, Olen O, Myrelid P, Ljung R, Strid H, et al. Validating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the Swedish National Patient Register and the Swedish Quality Register for IBD (SWIBREG) Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2017;52:216–221. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1246605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG, Bojesen SE. Statin use and reduced cancer-related mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1792–1802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frouws MA, Bastiaannet E, Langley RE, Chia WK, van Herk-Sukel MP, Lemmens VE, et al. Effect of low-dose aspirin use on survival of patients with gastrointestinal malignancies; an observational study. Br. J. Cancer. 2017;116:405–413. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hua X, Phipps AI, Burnett-Hartman AN, Adams SV, Hardikar S, Cohen SA, et al. Timing of Aspirin and Other Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Use Among Patients With Colorectal Cancer in Relation to Tumor Markers and Survival. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:2806–2813. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ekström N, Schiöler L, Svensson AM, Eeg-Olofsson K, Miao Jonasson J, Zethelius B, et al. Effectiveness and safety of metformin in 51 675 patients with type 2 diabetes and different levels of renal function: a cohort study from the Swedish National Diabetes Register. BMJ open. 2012;2:e001076. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craney TA, Surles JG. Model-Dependent Variance Inflation Factor Cutoff Values. Qual. Eng. 2002;14:391–403. doi: 10.1081/QEN-120001878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng J, Xie SH, Santoni G, Lagergren J. Population-based cohort study of diabetes mellitus and mortality in gastric adenocarcinoma. Br. J. Surg. 2018;105:1799–1806. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung, W. S., Le, P. H., Kuo, C. J., Chen, T. H., Kuo, C. F., Chiou, M. J. et al. Impact of metformin use on survival in patients with gastric cancer and diabetes mellitus following gastrectomy. Cancers10.3390/cancers12082013 LID - 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Seo, H. S., Jung, Y. J., Kim, J. H., Lee, H. H. & Park, C. H. The effect of metformin on prognosis in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Clin. Oncol.42, 909–917 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Cho, M. H., Yoo, T. G., Jeong, S. M. & Shin, D. W. Association of aspirin, metformin, and statin use with gastric cancer incidence and mortality: a nationwide cohort study. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila).10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-20-0123 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Courtois S, Lehours P, Bessede E. The therapeutic potential of metformin in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22:653–662. doi: 10.1007/s10120-019-00952-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daugan M, Dufay Wojcicki A, d’Hayer B, Boudy V. Metformin: an anti-diabetic drug to fight cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2016;113:675–685. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu G, Fang W, Xia T, Chen Y, Gao Y, Jiao X, et al. Metformin potentiates rapamycin and cisplatin in gastric cancer in mice. Oncotarget. 2015;6:12748–12762. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu X. Effect of metformin combined with chemotherapeutic agents on gastric cancer cell line AGS. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017;30:1833–1836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park JW, Lee JH, Park YH, Park SJ, Cheon JH, Kim WH, et al. Sex-dependent difference in the effect of metformin on colorectal cancer-specific mortality of diabetic colorectal cancer patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017;23:5196–5205. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i28.5196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data were retrieved from the Swedish Prescribed Drugs and Health Cohort. The original data are available from the registries listed above, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and therefore are not publicly available. Data may however be available through applications to these registries or reasonable request to the corresponding author (S.X.). The codes for the data analysis are archived by the first author (J.Z.).