Abstract

Background:

Clinical trials for antibiotics designed to treat hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonias (HABP/VABP) are hampered by difficulty making the diagnosis in a way that is acceptable to FDA and consistent with standards of care. We sought to identify risk factors that predispose children to HABP/VABP and to describe the epidemiology of pediatric HABP/VABP to identify laboratory and clinical features to improve pediatric HABP/VABP clinical trial efficiency.

Methods:

We prospectively reviewed the electronic medical records of patients <18 years of age admitted to intensive and intermediate care units (ICUs) if they received qualifying respiratory support or were started on antibiotics for a lower respiratory tract infection or undifferentiated sepsis. Subjects were followed until HABP/VABP was diagnosed or they were discharged from the ICU. Clinical, laboratory and imaging data were abstracted using structured chart review. We calculated the incidence of HABP/VABP and used a stepwise backward selection multivariable model to identify risk factors associated with development of HABP/VABP.

Results:

862 neonates, infants and children were evaluated for development of HABP/VABP. Ten percent (82/800) of those receiving respiratory support and 12% (103/862) overall developed HABP/VABP. Increasing age, shorter height/length, longer ICU length of stay, aspiration risk, blood product transfusion in the prior 7 days and frequent suctioning were associated with increased odds of HABP/VABP. The use of noninvasive ventilation and the use of gastric acid suppression were both associated with decreased odds of HABP/VABP.

Conclusion:

FDA-defined HABP/VABP occurred in 10–12% of pediatric patients admitted to intensive and intermediate care units. Risk factors vary by age group.

Keywords: antibiotic clinical trials, hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia, ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia, children

Summary:

The ability to prospectively identify children with high-risk features should allow for improved enrollment of those eligible for antibiotic trials for the treatment of hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia.

Introduction

Hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonias (HABP/VABP) are associated with significant mortality and morbidity for all age groups.1–3 HABP/VABP develops in the hospital environment, so causative pathogens can include multidrug-resistant organisms that require novel antimicrobials.4,5 Patient enrollment in clinical trials for novel antimicrobials for HABP/VABP is often limited by difficulties in diagnosing HABP/VABP.6

Improvements in early diagnosis are likely to result in more appropriate antibiotic therapy for infants and children with HABP/VABP.8 Earlier diagnosis of potentially eligible subjects would also allow prompt enrollment within 24 hours of starting a non-study antibiotic, which is a key inclusion criteria for HABP/VABP studies designed for regulatory agencies.7

We sought to identify risk factors that predispose children to HABP/VABP and to describe the epidemiology of pediatric HABP/VABP in order to discern features that could be used to facilitate early enrollment in HABP/VABP clinical trials, resulting in improved pediatric HABP/VABP clinical trial inclusion and exclusion criteria, and outcomes assessments.

Methods

In order to address the unmet need for novel antibiotic clinical trials, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the National Institutes of Health and other public and private partners developed the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (CTTI).9–11 This study was designed in cooperation with CTTI as part of the “Prospective Observational Study of the Risk Factors for Hospital-Acquired and Ventilator-Associated Bacterial Pneumonia (HABP/VABP)” protocol, which had two arms:1) adults ≥18 years old; and 2) children <18 years old. A common electronic data collection form was used for both arms. Project management and statistical analyses were performed independently for each arm. The pediatric findings are reported here as a vulnerable population with distinct epidemiologic and therapeutic needs

Study population

Electronic medical records of patients <18 years old who were hospitalized for ≥48 hours or re-admitted <7 days after discharge from an inpatient acute or chronic care facility and admitted to an intensive care unit or intermediate care unit were prospectively identified at 9 children’s hospitals from September 2016 to August 2017. At some of the participating hospitals, children receiving high-risk respiratory support could be cared for in intensive care units or in intermediate care units; for this reason, both unit types were monitored for subjects meeting inclusion criteria and are collectively referred to here as ICUs. Subjects were included if they met a priori high-risk criteria (Table 1), or were started on antibiotic therapy for a lower respiratory tract infection or undifferentiated sepsis.

Table 1.

High-risk and standard-risk enrollment criteria.

| <120 days old |

≥120 days |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk | Standard-risk | High-risk | Standard-risk |

| ≥ 5 days of endotracheal intubation | Antibiotics started for lower respiratory tract infection | ≥ 24 hours of: Mechanical ventilation via endotracheal intubation | Antibiotics started for lower respiratory tract infection |

| Antibiotics started for undifferentiated sepsis | New initiation of mechanical ventilation, CPAP, or BiPAP via tracheostomy | Antibiotics started for undifferentiated sepsis | |

| BiPAP or CPAP for any indication other than sleep apnea | |||

| High-flow supplemental 100% oxygen delivered at ≥ 1.5 LPM | |||

| High-flow supplemental oxygen delivered at ≥ 50% via facemask or tracheostomy collar | |||

| Supplemental oxygen delivered via partial or non-rebreather face mask | |||

CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; BiPAP: bi-level positive airway pressure; LPM: liters per minute

Patients were excluded if they were known to be pregnant, had lung cancer or another cancer with lung metastases, were on comfort measures, or had previously been included and treated for suspected HABP/VABP.

Data collection

Demographic data, comorbidities, reason for admission to the ICU, and ICU type were recorded. Medical records were reviewed on a daily basis for high-risk patients and twice weekly for standard-risk patients for the development of HABP/VABP. If antibiotics were initiated for a lower respiratory tract infection or undifferentiated sepsis, then vital signs in the prior 24 hours and laboratory study results (including microbiology culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing results) were also recorded. Subjects were followed until they met HABP/VABP criteria or were discharged from the ICU. Those who were still admitted to an ICU and had not developed HABP/VABP 8 weeks following the close of enrollment were censored without meeting the HABP/VABP definition by convention.

Definitions

The primary endpoint for the development of HABP/VABP was defined for this study as the FDA definition of HABP/VABP for clinical trials 7:

chest radiograph with a new or progressive infiltrate within 48 hours of meeting the other criteria;

≥1 of: new or worsening cough; dyspnea; tachypnea; increased sputum production; new onset of suctioned respiratory secretions; new requirement for invasive mechanical ventilation; hypoxemia (partial pressure of oxygen <60 mm of mercury measured by arterial blood gas or worsening [decrease >10%] of the ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen [PaO2/FiO2] or pulse oximetry reading of <90% or new supplemental oxygen requirement or greater than 50% increase in supplemental oxygen requirement for patients on chronic supplemental oxygen therapy); need for acute changes (≥20% increase in FiO2 or ≥3 cm H20 increase in positive end-expiratory pressure over the baseline daily minimum) after 2 days of stability in ventilator support;

≥1 sign of systemic inflammation: body temperature ≥38° Celsius or ≤35° Celsius; leukocytosis (total peripheral white blood cell count ≥10,000 cells/mm3); leukopenia, (total peripheral white blood cell count ≤4500 cells/mm3); greater than 15% immature neutrophils (bands) noted on peripheral blood film; elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) (≥5 times the upper limit of normal);

signs/symptoms of pneumonia first noted >48 hours after hospital admission or >48 hours after initiation of mechanical ventilation.

Frequent suctioning was defined as nasal, oropharyngeal, or tracheal suctioning occurring more frequently than every 2 hours. Aspiration risk was defined as having an abnormal swallow evaluation, documented aspiration pneumonitis or pneumonia, or receipt of enteral nutrition. Use of gastric acid suppression was defined as exposure to a proton pump inhibitor or H2 blocker during the current hospitalization.

Statistical analysis

The incidence of HABP/VABP was determined overall, for neonates <28 days old, infants <120 days old, and for children ≥120 days old. Neonates <28 days old were included in both the <28 days group and the <120 days group. For those receiving mechanical ventilation, we calculated the incidence of VABP per 1000 ventilator-days. For all included patients, we calculated the incidence of HABP/VABP per 1000 ICU-days. ICU-days included in the denominator were counted from admission to the ICU until discharge from the ICU or the diagnosis of HABP/VABP. We used a stepwise backward selection multivariable model to identify risk factors associated with HABP/VABP overall and for each age group. Sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values were calculated for leukocytosis and elevated CRP using the HABP/VABP case definition as the reference standard. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value <0.05. Data analysis was conducted using SAS (Cary, NC). The study was approved by each hospital’s Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent.

Results

We included 862 children. The great majority of included subjects, 800/862 (93%), met high-risk criteria due to receiving a qualifying respiratory support modality (Table 2). The median age was 1.2 years (25th, 75th percentiles: 0.2, 7.0) overall with a slight male predominance, 484/862 (56%). ICU-admission diagnosis and comorbidities varied by age group (Table 3). The most common reason for admission to the ICU was acute respiratory distress or failure, 407/862 (47%), followed by planned post-operative admission 112/862 (13%). Underlying respiratory disease was the most common comorbidity, 480/862 (56%). Only 107/862 (12%) had no underlying medical condition.

Table 2.

Demographics

| HABP/VABP N=103 (%) |

No HABP/VABP N=759 (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (minimum, maximum) | 0.8 (0.0, 17.6) | 1.2 (0.0, 17.9) |

| Median height, cm (minimum, maximum) | 66.5 (19.0, 181.0) | 73.7 (18.3, 184.0) |

| Median weight, kg (minimum, maximum) | 7.9 (0.4, 92.4) | 9.5 (0.4, 124.0) |

| High-risk criteria | ||

| Invasive mechanical ventilation >48 hours | 37 (36) | 382 (50) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation >5 days | 21 (20) | 185 (24) |

| New mechanical ventilation, BiPAP or CPAP via tracheostomy | 9 (9) | 56 (7) |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 12 (12) | 108 (14) |

| High-flow oxygen | 6 (6) | 15 (2) |

| Supplemental oxygen via partial or non-rebreather face mask | 1 (1) | 7 (1) |

| None | 21 (20) | 41 (5) |

| Median ICU length of stay at time of screening, days (minimum, maximum) | 5 (1, 163) | 4 (1, 297) |

| Primary ICU admission diagnosis | ||

| Acute respiratory failure or distress | 69 (67) | 338 (45) |

| Congenital heart defect | 4 (4) | 53 (7) |

| Acute renal failure or electrolyte abnormality | 1 (1) | 9 (1) |

| Altered mental status | 2 (2) | 14 (2) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 0 (0) | 10 (1) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1 (1) | 11 (1) |

| Planned post-operative admission | 5 (5) | 107 (14) |

| Severe sepsis/septic shock | 5 (5) | 31 (4) |

| Frequent or refractory seizures | 2 (2) | 36 (5) |

| Trauma | 2 (2) | 30 (13) |

| Other | 12 (12) | 120 (16) |

Table 3.

Underlying comorbidities for included patients.

| Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity | Overall N=862 (%) |

120 days to 18 years N=616 |

<120 days N=246 |

<28 days N=156 |

| None | 107 (12) | 61 (10) | 46 (19) | 25 (16) |

| Respiratory problem | 480 (56) | 361 (59) | 119 (48) | 75 (48) |

| Neurological problem | 361 (42) | 324 (53) | 37 (15) | 19 (12) |

| Cardiovascular problem | 188 (22) | 105 (17) | 83 (34) | 56 (36) |

| Gastrointestinal problem | 75 (9) | 56 (9) | 19 (8) | 11 (7) |

| Renal problem | 62 (7) | 45 (7) | 17 (7) | 15 (10) |

| Hematology/oncologic problem | 49 (6) | 49 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Prior organ transplant | 21 (2) | 21 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Endocrine/rheumatologic problem | 17 (2) | 17 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

HABP/VABP Incidence

Among the 862 participants, 103 (12%) patients ultimately met the FDA definition of HABP/VABP: 23/156 (15%) neonates, 34/246 (14%) infants, and 69/616 (11%) children. The overall HABP/VABP incidence observed in our cohort was 1.9 HABP/VABP cases per 1000 ICU-days overall (Table 4). HABP/VABP occurred in 10% of patients receiving respiratory support in all age groups: 82/800 overall, 13/132 neonates, 21/206 infants, 61/594 children. For participants supported by mechanical ventilation, the VABP rate was 3.9 cases per 1000 ventilator-days overall. For those who only received non-invasive mechanical ventilation, HABP/VABP occurred in 11/96 (12%). HABP/VABP following non-invasive mechanical ventilation was more common in infants than the other age groups but the numbers were small, 3/9 (33%) vs. 1/5 (20%) in neonates and 11/96 (12%) in children.

Table 4.

Incidence of HABP/VABP.

| Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Overall | ≥120 days | <120 days | <28 days |

| All included subjects* | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.4 |

| Received mechanical ventilation† | 3.9 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 4.1 |

HABP/VABP cases per 1000 days hospitalized in an intermediate or intensive care unit;

HABP/VABP cases per 1000 ventilator-days

Risk Factors Associated with HABP/VABP

On multivariable regression of the overall study population, increasing age, shorter height/length, longer ICU length of stay, aspiration risk, blood product transfusion in the prior 7 days, and frequent suctioning were associated with increased odds of HABP/VABP (Table 5). The use of noninvasive ventilation and gastric acid suppression were associated with decreased odds of HABP/VABP.

Table 5.

Factors associated with HABP/VABP in high-risk patients, adjusted odds ratio* (95% confidence interval)

| Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Overall | 120 days to 18 years | <120 days | <28 days |

| Age | 1.22 (1.08, 1.37) † | 1.17 (1.03, 1.34)† | 1.02 (0.99, 1.04) ‡ | 0.81 (0.66, 1.01)‡ |

| Height, cm | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | ||

| Weight, kg | 0.45 (0.26, 0.79) | 0.43 (0.21, 0.87) | ||

| ICU length of stay, days | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.04) | 1.07 (0.99, 1.15) |

| Aspiration risk | 3.81 (2.17, 6.68) | 4.39 (2.34, 8.23) | ||

| Noninvasive ventilation | 0.55 (0.32, 0.93) | 0.53 (0.28, 0.99) | 0.41 (0.14, 1.21) | 0.31 (0.07, 1.32) |

| Vasopressor/inotropic therapy | 0.67 (0.39, 1.13) | 0.38 (0.11, 1.31) | ||

| Corticosteroid use at current hospitalization | 1.74 (0.87, 3.46) | |||

| Proton pump or H2-blocker therapy | 0.37 (0.22, 0.64) | 0.46 (0.25, 0.84) | 0.24 (0.07, 0.85) | |

| Blood product transfusion in prior 7 days | 1.82 (1.02, 3.24) | 2.96 (0.91, 9.66) | ||

| Frequent suctioning | 3.64 (2.17, 6.12) | 3.47 (1.90, 6.35) | 7.32 (2.10, 25.47) | 5.71 (1.32, 24.7) |

| Invasive monitoring | 0.17 (0.01, 2.05) | |||

Stepwise multivariable logistic regression beginning with the variables: age; sex; height; weight; hospital admission type (emergent surgical, elective surgical or non-operative); admission source; hospital length of stay at screening; ICU length of stay at screening; primary ICU admission diagnosis; aspiration risk; medical comorbidities; type of ventilation; duration of ventilation; receipt of enteral nutrition; inotropic therapy; chemotherapy during current admission; biologic agents during current admission; corticosteroids during current admission; acid suppression therapy; blood product transfusion in the last 7 days; systemic antibiotics within the last 90 days; frequent oral, nasotracheal or tracheal suctioning; massive volume resuscitation; and invasive monitoring. Each factor is adjusted for all other factors;

years,

days

By age group, factors associated with HABP/VABP on multivariable analysis differed. Presence of an aspiration risk factor increased the odds of protocol-defined HABP/VABP (odds ratio [OR]=4.39; 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.34, 8.23), for children, but did not contribute to the model at all for infants or neonates. Use of gastric acid suppression reduced the odds of HABP/VABP for children (OR=0.46; 95% CI 0.25, 0.84) and for infants (OR=0.24; 95% CI 0.07, 0.85), but not for neonates.

Leukocytosis and CRP had poor sensitivity overall (Table 6). The specificity and negative predictive values were much better than sensitivity among all age groups. Test characteristics of procalcitonin were not able to be assessed because only 3 patients had this test performed.

Table 6.

Test characteristics of leukocytosis and elevation of C-reactive protein for the diagnosis of HABP/VABP.

| Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test characteristic | Overall (%) | 120 days to 18 years (%) | <120 days (%) | <28 days (%) |

| Leukocytosis* | ||||

| Sensitivity | 64 | 52 | 88 | 91 |

| Specificity | 91 | 92 | 89 | 88 |

| Positive predictive value | 32 | 27 | 40 | 42 |

| Negative predictive value | 98 | 97 | 99 | 99 |

| Elevated C-reactive protein† | ||||

| Sensitivity | 40 | 42 | 38 | 27 |

| Specificity | 96 | 95 | 97 | 97 |

| Positive predictive value | 36 | 32 | 50 | 43 |

| Negative predictive value | 96 | 97 | 95 | 94 |

peripheral white blood cell count ≥10,000 cells/mm3;

≥5 times the upper limit of normal

HABP/VABP Microbiology

Most patients who were started on antibiotics for suspected HABP/VABP or undifferentiated sepsis did not have lower respiratory tract cultures obtained prior to antibiotics being started. Nevertheless, for those patients who were ultimately diagnosed with HABP/VABP, most had a positive culture from the lower respiratory tract, sputum or blood culture, 73/103 (71%), possibly representing the pathogen responsible for the pulmonary deterioration, but also perhaps representing a colonizer in children with an alternative cause of deterioration. Staphylococcus aureus was the most common pathogen identified among pediatric patients diagnosed with HABP/VABP who had a positive culture, 33/73 (45%) (Table 7). Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia were also common, 27/73 (37%) and 12/73 (16%), respectively. For infants and neonates, Staphylococcus aureus remained the predominant pathogen; Stenotrophomonas maltophilia was only identified in 1 infant (4%) and in no neonates. Resistance to broad-spectrum antibiotics was uncommon overall, but 33% of Acinetobacter species, 29% of Enterobacter species (including 1 [14%] isolate resistant to carbapenems), and 7% of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates (including 2 [7%] resistant to carbapenems) were resistant to cefepime. Among Staphylococcus aureus isolates, only 16% were resistant to methicillin (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA]) but 18% were resistant to clindamycin. Five of the 9 (55%) centers had at least 1 case of HABP/VABP due to MRSA.

Table 7.

Organisms among infants and children with HABP/VABP who had a positive lower respiratory tract, sputum or blood culture.

| Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Overall N=73 (%) |

120 days to 18 years N=50 (%) |

<120 days N=23 (%) |

<28 days N=14 (%) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 33 (45) | 19 (38) | 14 (61) | 8 (57) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 27 (37) | 22 (44) | 5 (22) | 1 (7) |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 12 (16) | 11 (22) | 1 (4) | 0 |

| Serratia species | 9 (12) | 7 (14) | 2 (9) | 0 |

| Klebsiella species | 8 (11) | 4 (8) | 4 (17) | 3 (21) |

| Acinetobacter species | 7 (10) | 5 (10) | 2 (9) | 1 (7) |

| Enterobacter species | 7 (10) | 5 (10) | 2 (9) | 2 (14) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 4 (6) | 1 (2) | 3 (13) | 2 (14) |

| Escherichia coli | 4 (6) | 1 (2) | 3 (13) | 3 (21) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 4 (6) | 4 (8) | 0 | 0 |

| Other organism | 28 (38) | 20 (40) | 8 (35) | 5 (36) |

Discussion

HABP/VABP as defined by the FDA was common in this cohort of infants and children, occurring in 10% of patients receiving respiratory support. Risk factors associated with HABP/VABP varied by patient age.

We found that increasing age was associated with slightly increased adjusted odds of HAPB/VABP for children. Conversely, for infants and neonates, increasing weight reduced the odds of HABP/VABP. It is possible that much of the reduction in HABP/VABP risk was attributable to increases in the diameter of the bronchi leading to improvements in pulmonary clearance as the infants and neonates grew.12 Chest wall strength may also be improved with somatic growth leading to improved lung recruitment.13

Although comorbidities were not associated with HABP/VABP on the multivariable analysis, respiratory problems and neurologic problems were more common among children who developed HABP/VABP than among those who did not. Neurologic diseases are often associated with depressed respiratory effort and abnormal or absent gag reflex which may lead to increased risks of HABP/VABP.14 In our multivariable model, aspiration risk increased the odds of HABP/VABP nearly 4-fold. Aspiration risk is quite common among children with neurologic impairment and serves as a possible link between neurologic disease and pneumonia.15

In our cohort, blood product transfusion in the prior 7 days increased the odds of HABP/VABP. The underlying mechanism is unknown, but increased risk of HABP/VABP following transfusion has been described in adults following cardiac surgery16 and liberal transfusion strategies have been associated with an increased risk of nosocomial infection, including HABP/VABP.17 It is possible that the transfusion itself confers an increased risk or that transfusion serves as a surrogate for underlying degree of illness or another factor that increases HABP/VABP risk. We were not able to evaluate this finding further due to the observational nature of our study but additional investigation into this association in children appears warranted.

Prior studies have found the incidence of pediatric HABP/VABP to be as low as 2%.18,19 Other studies of young infants have reported incidence proportions of 12–13%.2,20 This may be due to a number of factors: 1) HABP/VABP diagnosis can be difficult to make; 2) surveillance techniques that rely on a positive culture may miss cases because cultures are either not obtained or are obtained after antibiotics have been administered21; and 3) some centers may be hesitant to document the HABP/VABP diagnosis in the medical chart due to financial and other penalties associated with hospital-acquired infections, despite an infection being present and being treated.

Since one goal of this study was to estimate the proportion of children receiving respiratory support who would ultimately become eligible to participate in a clinical trial of antibiotics for HABP/VABP, we used the FDA-definition of the condition with clarification of clinical symptoms using the CDC PNU1 and PNU2 definitions7,22; however, many different definitions for HABP and VABP have been used.23–25 The variation in definitions has limited the ability of HABP/VABP research to be combined to generate more generalizable findings and has prevented the development of pediatric-specific prevention and treatment guidelines.18 Furthermore, definition variations make it difficult to understand the scope of the problem since different definitions often do not identify the same patients within a cohort of at-risk children: one study of 127 children found a similar incidence of VABP when the PNU criteria were used (11%) vs. the adult ventilator associated event-VABP (10%), but that many children were in only one group and not the other.26 Additionally, they found that children with VABP defined by the new adult definition had increased mortality, but not children with VABP defined by PNU criteria.26 Although leukocytosis and elevated CRP are often used to support a diagnosis of HABP/VABP, the current study showed a lack sensitivity but good negative predictive value. Accordingly, normal white blood cell counts and CRP can reasonably be used to shift the focus away from HABP/VABP as a cause of symptoms. In our study, patients could meet the FDA definition of HABP/VABP by having a peripheral white blood cell count >10,000 cells/mL combined with respiratory symptoms. Most studies of pediatric infections have defined leukocytosis as a white blood cell count >15,000 cells/mL.27 However, a white blood cell count >10,000 cells/mL has been shown to have a negative predictive value of 99.7% for the diagnosis of pneumococcal bacteremia so this cutpoint may have some utility in ruling out bacterial disease in children.28 The low cutpoint was used in our study because of the common data collection form across the pediatric and adult arms of the study. This demonstrates some of difficulties inherent in trying to adapt adult studies for efficient data-collection in children: not all data elements and definitions used for adults, particularly with respect to congenital anatomic, metabolic or genetic abnormalities, are applicable to pediatric populations.

The national adult HABP/VABP guidelines recommend that definitive HABP/VABP therapy be tailored to culture results.29 However, in our cohort, only 33% of patients had lower respiratory tract cultures obtained. The optimal method for obtaining cultures has not been well defined for infants and children, with little data to demonstrate that a positive respiratory tract culture is proof of HABP/VABP. The CDC recommends obtaining quantitative cultures from the lower respiratory tract;22 however, tracheal aspirates are the most common specimen type collected in infants and children and most laboratories do not quantitate this type of culture.30 Tracheal aspirates have poor specificity, cannot differentiate between colonization and infection, and demonstrate bacterial growth nearly universally if the endotracheal tube has been in place >10 days.31 Without adequate culture results to make an accurate diagnosis and guide therapy, unnecessarily broad antibiotics may be used, especially if the adult guidelines for empirical therapy are applied. For infants, cultures were obtained infrequently, and these patients have a microbial epidemiology that is quite distinct from older patients. Improved methods of obtaining cultures from the lower respiratory tract in infants and children and guidance on interpreting their results are needed in order to improve the diagnosis and treatment of HABP/VABP.

Our study had several important strengths. First, we included infants and children from 9 hospitals, whereas most prior studies of HABP/VABP in children are limited to single centers. Second, medical records were reviewed daily for children receiving respiratory support. Daily surveillance of patient data has been shown to result in greater identification of nosocomial infections compared to twice weekly surveillance.32 Finally, we included infants and children prospectively and applied FDA and CDC PNU1 and PNU2 criteria as diagnostic criteria rather than relying on diagnoses recorded in the medical record.7,22

Our study also had several limitations. First, this was an observational study and diagnostic and treatment recommendations were not provided to the participating sites or to the treating clinicians. Second, we did not assess whether sites had a HABP/VABP prevention bundle program implemented nor if they were adherent to the bundle requirements. We did attempt to obtain information on some important prevention measures that are common components of HABP/VABP-prevention bundles: use of acid-suppressing medication and use of frequent suctioning. We did not evaluate for the use of oral hygiene measures or head-of-bed elevation. Third, we attempted to define the outcome of HABP/VABP by using the rigorous FDA and CDC definitions; however, these may not be the best diagnostic criteria to use for children. New criteria have been adopted by the CDC for use in adults which do not require radiography changes for diagnosis.33 We were unable to quantify how many children would have met the alternate definition for possible VABP had we applied this definition to our study population. Fourth, we report only positive cultures, most often “tracheal aspirates” (not quantitative cultures); therefore, our data may overestimate the rate of bacterial pneumonia. Fifth, viral pneumonias are much more common in children than adults, including nosocomial pneumonia.34 Nevertheless, we did not collect data on viral infections; an unknown proportion of children who had respiratory deterioration in our study and were considered to have HABP/VABP may have had primary infection or co-infection with viral pathogens. Lastly, not all pediatric comorbidities were represented on the adult-based data collection forms. Sites were instructed to select the comorbidity that most closely approximated each patient’s underlying conditions. In order to improve consistency among sites, sites were asked to code neonatal respiratory distress syndrome and meconium aspiration syndrome as “ARDS”; grade 3 and 4 intraventricular hemorrhage as “cerebrovascular accident”, cardiac contusion as “heart failure”, viral bronchiolitis as “bronchitis” and cerebral palsy as “impaired mobility” and/or “dementia/cognitive impairment” as relevant to the patient.

In summary, HABP/VABP occurred in 10% of hospitalized infants and children receiving respiratory support. Increasing age, shorter height/length, longer ICU length of stay, aspiration risk, blood product transfusion in the prior 7 days, and frequent suctioning were associated with increased odds of HABP/VABP. The use of noninvasive ventilation and proton pump inhibitors or H2-blockers were associated with decreased odds of HABP/VABP. Lower respiratory tract cultures were infrequently obtained, but when collected, demonstrated Staphylococcus aureus as the most common pathogen. Increased attention to patients with high-risk features could allow for improved identification of subjects eligible for HABP/VABP antibiotic trial enrollment. Additional studies to assess risk factors for pediatric HABP/VABP that address pediatric comorbid conditions and include a complete assessment of potential bacterial or viral pathogens by culture, polymerase chain reaction, or next generation sequencing are needed.

Supplementary Material

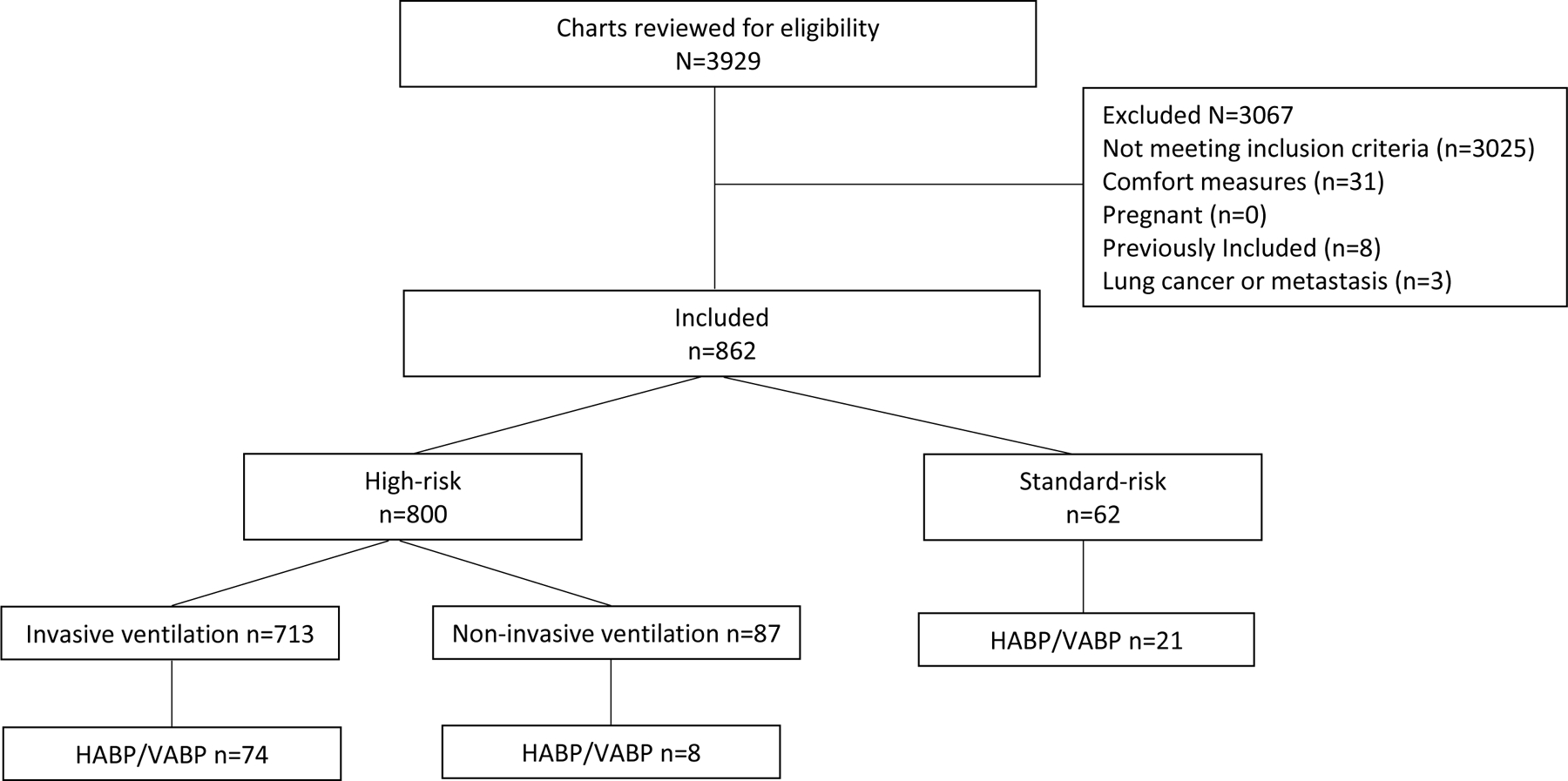

FIGURE 1.:

Study population. This figure displays the study population, including exclusions.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded under NICHD contract HHSN2752010000031 Task Order#42 for the Pediatric Trials Network (PI Benjamin) and with partial funding through FDA grant R18FD005292 – Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative. Views expressed in written materials or publications and by speakers and moderators do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services or does any mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organization imply endorsement by the United States Government.

The PTN Steering Committee Members: Daniel K. Benjamin Jr., Christoph P Hornik, Kanecia O. Zimmerman, Phyllis Kennel, and Rose Beci, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC; Chi Dang Hornik, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC; Gregory L. Kearns, Scottsdale, AZ; Matthew Laughon, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC; Ian M. Paul, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA; Janice Sullivan, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY; Kelly Wade, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA ; Paula Delmore, Wichita Medical Research and Education Foundation, Wichita, KS

PTN Publications Committee: Chaired by Thomas Green, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: Perdita Taylor-Zapata, June Lee

Study Site Coordinators and PTN Study Team: Patricia Carper, Amyee McMonagle, Amy Shelly, and Jennifer Stokes, Penn State Milton S Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA; Deana Rich, Lincoln Smith, Courtney Merritt , Erin Sullivan, and Nastassya West, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA; Sara Hingtgen, Shannon Skochko, and Michael Farrell, Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, CA; Noreen Jeffrey and Samar Musa, UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; Ofelia Vargas-Shiraishi, Nick Anas, and Cathy Flores, Children’s Hospital of Orange County, Orange, CA; Michelle Kroeger and Kristen Buschle, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Cincinnati, OH; Elizabeth Lang, Mattel Children’s Hospital UCLA, Los Angeles ,CA; Lora Hindenburg, Inova Children’s Hospital, Falls Church, VA; Nicole Maslanka and Travis Stewart, Atlanta Institute for Medical Research, Decatur, GA; Study operation team at Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC: Beth Evans (Lead Clinical Research Associate [CRA]), Elizabeth Mocka and Anastasia Ngugi (CRAs), Owen Townes (Clinical Data Specialist), Jackie Huvane (Data Manager), Sara Calvert (Project Leader, CTTI), Peidi Gu (Project Leader, Adult Arm), Ivra Bunn (Clinical Trials Specialist)

References

- 1.Melsen WG, Rovers MM, Groenwold RH, et al. Attributable mortality of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised prevention studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13(8):665–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thatrimontrichai A, Rujeerapaiboon N, Janjindamai W, et al. Outcomes and risk factors of ventilator-associated pneumonia in neonates. World J Pediatr 2017;13(4):328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gautam A, Ganu SS, Tegg OJ, Andresen DN, Wilkins BH, Schell DN. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in a tertiary paediatric intensive care unit: a 1-year prospective observational study. Crit Care Resusc 2012;14(4):283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maruyama T, Fujisawa T, Ishida T, et al. A Therapeutic Strategy for All Pneumonia Patients: A 3-Year Prospective Multicenter- Cohort Study Using Risk Factors for Multidrug Resistant Pathogens To Select Initial Empiric Therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidd JM, Kuti JL, Nicolau DP. Novel pharmacotherapy for the treatment of hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by resistant gram-negative bacteria. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2018;19(4):397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barriere SL. Challenges in the design and conduct of clinical trials for hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia: an industry perspective. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51 Suppl 1:S4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Administration FaD. Draft guidance for industry: hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia: developing drugs for treatment In:2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley JS. Considerations unique to pediatrics for clinical trial design in hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51 Suppl 1:S136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative https://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/. Accessed 9/18/2018.

- 10.Knirsch C, Alemayehu D, Botgros R, et al. Improving Conduct and Feasibility of Clinical Trials to Evaluate Antibacterial Drugs to Treat Hospital-Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia and Ventilator-Associated Bacterial Pneumonia: Recommendations of the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative Antibacterial Drug Development Project Team. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63 Suppl 2:S29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noel GJ, Nambiar S, Bradley J, Program CTTIsPADD. Advancing Pediatric Antibacterial Drug Development: A Critical Need to Reinvent our Approach. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2019;8(1):60–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hislop AA, Haworth SG. Airway size and structure in the normal fetal and infant lung and the effect of premature delivery and artificial ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;140(6):1717–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gappa M, Pillow JJ, Allen J, Mayer O, Stocks J. Lung function tests in neonates and infants with chronic lung disease: lung and chest-wall mechanics. Pediatr Pulmonol 2006;41(4):291–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gulati IK, Shubert TR, Sitaram S, Wei L, Jadcherla SR. Effects of birth asphyxia on the modulation of pharyngeal provocation-induced adaptive reflexes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015;309(8):G662–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagos-Guimarães HN, Teive HA, Celli A, et al. Aspiration Pneumonia in Children with Cerebral Palsy after Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Study. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2016;20(2):132–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horvath KA, Acker MA, Chang H, et al. Blood transfusion and infection after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;95(6):2194–2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rohde JM, Dimcheff DE, Blumberg N, et al. Health care-associated infection after red blood cell transfusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2014;311(13):1317–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beardsley AL, Nitu ME, Cox EG, Benneyworth BD. An Evaluation of Various Ventilator-Associated Infection Criteria in a PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016;17(1):73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cirulis MM, Hamele MT, Stockmann CR, Bennett TD, Bratton SL. Comparison of the New Adult Ventilator-Associated Event Criteria to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Pediatric Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia Definition (PNU2) in a Population of Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury Patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016;17(2):157–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar S, Shankar B, Arya S, Deb M, Chellani H. Healthcare associated infections in neonatal intensive care unit and its correlation with environmental surveillance. J Infect Public Health 2018;11(2):275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Llitjos JF, Amara M, Benzarti A, Lacave G, Bedos JP, Pangon B. Prior antimicrobial therapy duration influences causative pathogens identification in ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Crit Care 2018;43:375–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prevention CfDCa. Pneumonia (Ventilator-associated [VAP] and non-ventilator-associated Pneumonia [PNEU]) Event In:2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bechard LJ, Duggan C, Touger-Decker R, et al. Nutritional Status Based on Body Mass Index Is Associated With Morbidity and Mortality in Mechanically Ventilated Critically Ill Children in the PICU. Crit Care Med 2016;44(8):1530–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narayanan A, Dixon G, Chalkley S, Ray S, Brierley J. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in children: comparing the plethora of surveillance definitions. J Hosp Infect 2016;94(2):163–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cocoros NM, Priebe GP, Logan LK, et al. A Pediatric Approach to Ventilator-Associated Events Surveillance. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2017;38(3):327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iosifidis E, Chochliourou E, Violaki A, et al. Evaluation of the New Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Ventilator-Associated Event Module and Criteria in Critically Ill Children in Greece. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016;37(10):1162–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yo CH, Hsieh PS, Lee SH, et al. Comparison of the test characteristics of procalcitonin to C-reactive protein and leukocytosis for the detection of serious bacterial infections in children presenting with fever without source: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60(5):591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mintegi S, Benito J, Sanchez J, Azkunaga B, Iturralde I, Garcia S. Predictors of occult bacteremia in young febrile children in the era of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugated vaccine. Eur J Emerg Med 2009;16(4):199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63(5):e61–e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venkatachalam V, Hendley JO, Willson DF. The diagnostic dilemma of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2011;12(3):286–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willson DF, Conaway M, Kelly R, Hendley JO. The lack of specificity of tracheal aspirates in the diagnosis of pulmonary infection in intubated children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014;15(4):299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ford-Jones EL, Mindorff CM, Langley JM, et al. Epidemiologic study of 4684 hospital-acquired infections in pediatric patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1989;8(10):668–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prevention CfDCa. Device-associated module ventilator-associated event (VAE) In:2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chow EJ, Mermel LA. Hospital-Acquired Respiratory Viral Infections: Incidence, Morbidity, and Mortality in Pediatric and Adult Patients. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017;4(1):ofx006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.