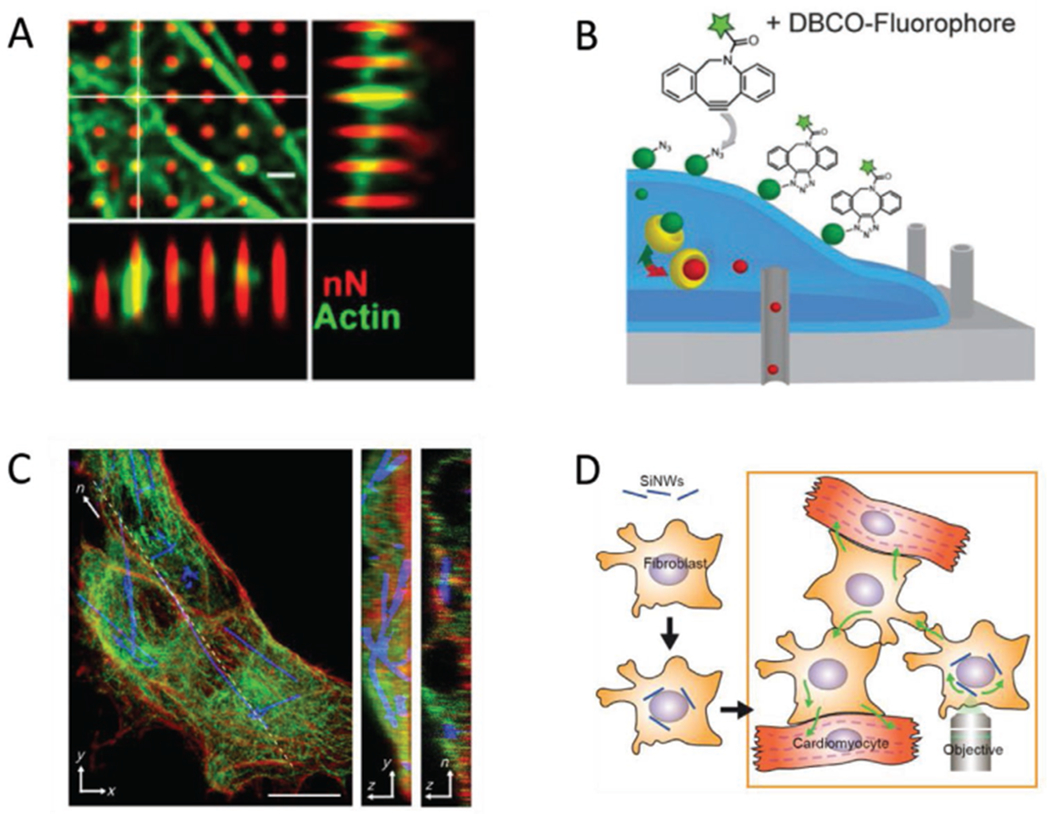

Figure 2.

Selected examples of intracellular nano-biointerfaces. A) Human mesenchymal stem cells grown on porous silicon nanoneedles. The cytoskeletal protein actin (green) can accumulate around nanoneedles (red). Scale bar = 10 μm. Adapted with permission.[112] Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. B) Diagram of nanostraws being used to deliver markers of protein glycosylation. The nanostraws (gray cylinders) can access the intracellular space, so that an azidosugar cargo (red spheres) can enter the cell. In the instance pictured, the azidosugar is subsequently converted to sialic acid groups (green spheres) and transported to the cell surface, where they can be fluorescently labeled. Adapted with permission.[52] Copyright 2017, John Wiley and Sons. C) Silicon nanowires spontaneously internalized by human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Actin (red) and tubulin (green) indicate the cytoskeletal architecture of the cell, showing that nanowires (blue) incorporate well with the cytoskeleton. Scale bar = 10 μm. Reproduced with permission.[40] Copyright 2016, American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). D) Diagram of how hybridized cells can be employed to access cells that do not normally internalize nanowires. In this instance, cardiomyocytes do not internalize the cells, but they can interface with cardiac myofibroblasts, which do. The myofibroblast-nanowire hybrids can then be stimulated such that the resultant effects are transmitted to the myocytes. Adapted with permission.[54] Copyright 2019, National Academy of Sciences.