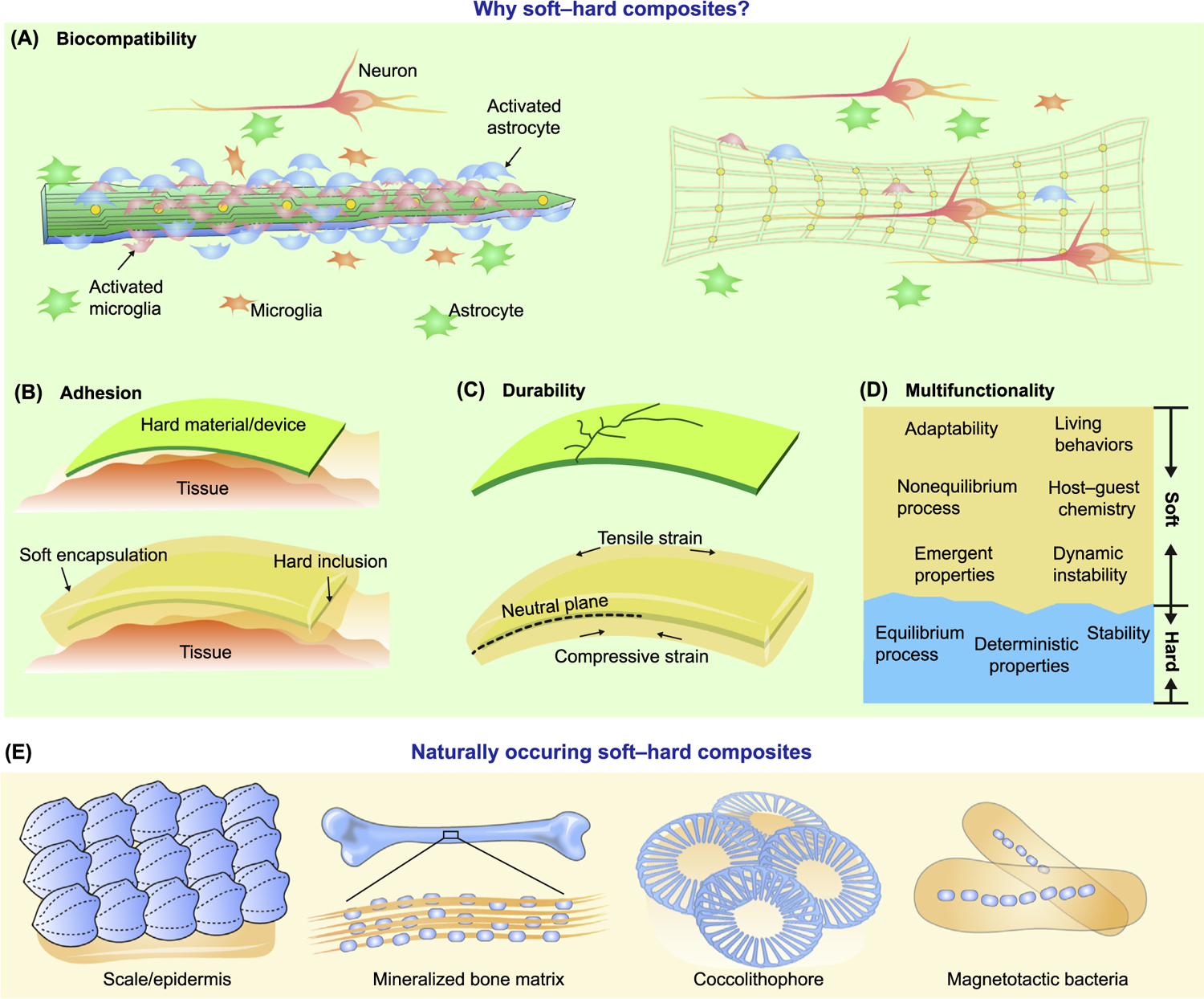

Figure 1. Soft–Hard Composites May Establish Better Biointerfaces and Are Common in Nature.

(A) Rigid devices usually trigger significant inflammatory response upon implantation, activating microglia and astrocytes. Soft–hard composites have lower effective modulus and are more biocompatible. (B) Hard materials/devices do not conform well to the curvilinear tissue surfaces. With either partial (see Figure 1 in Box 1, row 1) or complete coverage by the soft materials, the adhesion at the device/tissue interface gets improved. (C) Hard materials are usually brittle, easily fracture under strain, and display poor impact absorption. Incorporation of soft components alleviate such issues by, for example, producing a neutral stress plane for the hard material. (D) Soft and hard materials have different properties. Integration of both in a composite can yield multiple functions. (E) Diverse naturally occurring soft–hard composites. Solid scales (blue) attached to a soft epidermis layer (orange) form a bendable composite. The mineralized matrix of the bone consists of homogenously distributed soft organic components (mainly type I collagen, orange) and hard inorganic components (mainly hydroxyapatite, blue). A coccolithophore is enclosed in a collection of coccoliths which make up its exoskeleton or coccosphere. Magnetotactic bacteria use specialized organelles called magnetosomes to store magnetic material.