Abstract

The need for alternative source of fuel has demanded the cultivation of 3rd generation feedstock which includes microalgae, seaweed and cyanobacteria. These phototrophic organisms are unique in a sense that they utilise natural sources like sunlight, water and CO2 for their growth and metabolism thereby producing diverse products that can be processed to produce biofuel, biochemical, nutraceuticals, feed, biofertilizer and other value added products. But due to low biomass productivity and high harvesting cost, microalgae-based production have not received much attention. Therefore, this review provides the state of the art of the microalgae based biorefinery approach to define an economical and sustainable process. The three major segments that need to be considered for economic microalgae biorefinery is low cost nutrient source, efficient harvesting methods and production of by-products with high market value. This review has outlined the use of various wastewater as nutrient source for simultaneous biomass production and bioremediation. Further, it has highlighted the common harvesting methods used for microalgae and also described various products from both raw biomass and delipidified microalgae residues in order to establish a sustainable, economical microalgae biorefinery with a touch of circular bioeconomy. This review has also discussed various challenges to be considered followed by a techno-economic analysis of the microalgae based biorefinery model.

Keywords: Microalgae, Wastewater, Biorefinery, Delipidified biomass, Circular economy, Zero waste

Introduction

The 3rd generation biofuels obtained from microalgae has garnered interest in the recent times, owing to its advantages over the 1st and 2nd generation of biofuels. The earlier generations of biofuel are derived from agricultural land and forest residues thereby requiring a significant amount of fertiliser, water and large areas of crop land (Ullah et al. 2018). This directly or indirectly impacts food security predominantly in the developing nations (Borse and Sheth 2017). On the other hand, microalgae have various advantages over land- based crops for oil production. The simple structure and high photosynthetic efficiency results in higher oil yield per unit area than other oilseed crops. Also, algal growth is not dependent on arable land and fresh water for its cultivation and can be cultivated on marginal land using marine water or industrial effluent and therefore, does not compete for resources that are associated with conventional agriculture. Microalgae cultivation does not require addition of pesticides or herbicides and its cultivation when coupled with CO2 and nutrient uptake from industrial gases and effluents, respectively, may solve some of the major environmental concerns faced by the world. In addition to solving environmental concerns, several products viz. biofuels, pigments, nutraceuticals, fertilizers and animal feed could be produced from the microalgal biomass (Levasseur et al. 2020).

Biofuels have the capability to eliminate the dependency on fossil fuels as well as economic disturbances caused due to fluctuations in prices of each fossil fuel. Also, biofuels have additional advantage of reducing the green house gases (GHG) thereby improving the air quality. Microalgae are driven by solar energy using CO2 for performing photosynthesis and store energy in the form of lipid, thereby cleaning environment and generate lipid. Microalgae has the potential to convert 183 tons of CO2 which translates into 100 tons of microalgal biomass which is higher as compared to higher plants (Eloka-Eboka et al. 2017). Thus, microalgae when utilised in a holistic manner for the development of biofuels and other value added products has the potential to provide alternative sources of various products, there by maintaining a low inflation rate especially of biofuels while achieving the mandates of a clean and green environment (Milano et al. 2016). Microalgae besides biofuels are a potential source of substrates for a variety of industries including food, feed, fertilizers, nutrition and cosmetics (Mathimani and Pugazhendhi 2019; Kumar et al. 2020).

However, cost of nutrients for microalgal cultivation is a major hindrance in commercialization of microalgae based industries. Here, industrial effluents rich in nutrients for microalgae come to the rescue. Along with its cultivation, microalgae also serve the purpose of bioremediation of industrial effluent and recover clean water thereby reducing the impact of environmental concern of fresh water shortage. Fresh water microalgae sp. such as Chlorella has been reported to accumulate up to 30% lipids when cultivated in wastewater (Chen et al. 2015).

A salient feature of microalgae is its capacity to be productive throughout the year which is not possible with most of the crops. Also, high oil yield per unit area is obtained from microalgae as compared to terrestrial crops without addition of pesticides and herbicides which is in-line with world’s goal of energy independence (Hannon et al. 2010; Benemann and Oswald 1996). However, microalgae production at large scale is significantly expensive as compared to production of conventional crops owing to hefty usage of water and nutrients majorly carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus sources (Dalrymple et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2011a, b; Leite et al. 2013). Since these elements are also required for conventional crop cultivation, its application for microalgae cultivation poses a direct competition and threat for fertilizers (Peccia et al. 2013).

Another critical obstacle in the path of microalgae cultivation at commercial scale is the fresh water usage. Global consumption of fresh water stands at around 4 trillion cubic metres every year (www.theworldcounts.com). Moreover, total N and P concentration can be between 10 and 100 mg/L in municipal effluent and can reach upto 1000 mg/L in industrial effluent (Chen et al. 2015). Release of such high concentrations of N and P in water bodies would lead to damage of aquatic ecosystem due to eutrophication in water bodies. Microalgae have shown potential to competently remove nitrogen, phosphorus and toxic metals from a variety of effluent streams viz. municipal, agricultural and industrial which makes microalgae a potential candidate for biological remediation of wastewater (Cai et al. 2013; Markou and Georgakakis 2011).

Microalgae unlike other feedstocks have an upper hand due to (a) no competition for fresh water and arable land; (b) high growth rate; (c) high oil content (up to 40%) (d) reduces carbon footprint thereby reduces green house gases and prevents global warming (e) provides biological treatment for industrial effluent unlike conventional treatment methods employing harsh chemicals and energy intensive physical treatment; (f) microalgal biomass generated is rich in lipid, protein, starch which has potential application in biofuel, aquafeed and fertiliser industries (Cai et al. 2013).

Many researchers have published reviews based on microalgae derived products, upstream–downstream methods in a microalgae based biorefinery model and bioremediation. This review not only provides a state-of-the-art of the microalgae cultivation and harvesting techniques but also highlighted detailed insights into various products from both raw and delipidified microalgae biomass. Delipidified microalgae products are mostly neglected in published microalgae based reviews. This review has highlighted delipidified microalgae as a major source of microalgae biorefinery product in order to make it a sustainable circular bioeconomy model. It has also emphasised on the bottlenecks of large scale production of microalgae biomass and products and concluded with few solutions. This review has also analysed techno-economics of different microalgae models so as to present a complete picture of microalgae-based industrial scenario and its current status. Techno-economic sustainability analysis highlights the key areas where the improvements are needed to make microalgae model feasible and successful in the long run. This review has further highlighted an in-house case study based on bioconversion of microalgae biomass in order to provide some realistic scenario of microalgae biorefinery.

Integrated microalgae biorefinery

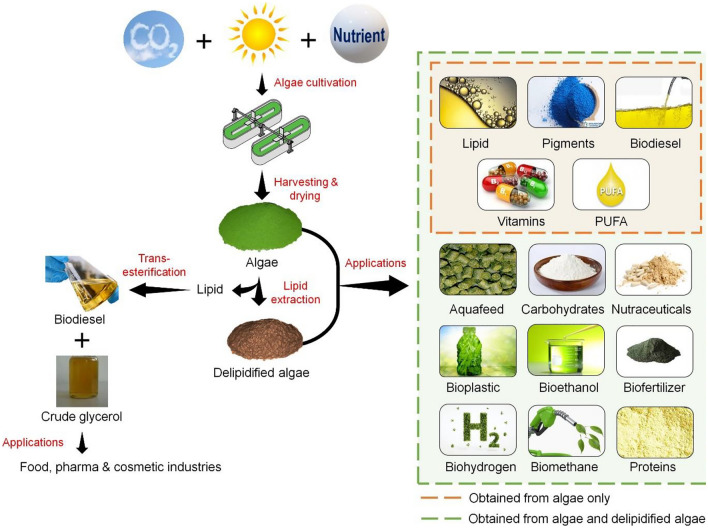

The microalgae biorefinery approach is a continuous process which integrates simultaneous cultivation, extraction and production of energy and other value added products from microalgae biomass (Fig. 1). Microalgae are photosynthetic entities which has the ability to mitigate greenhouse gases like CO2 by utilising it for growth and metabolism thereby combating global warming (Yadav et al. 2019). Although microalgae are freshwater organisms but they have the potential to adapt and grow in marine water and industrial wastewater. This in turn approves the phenomena of conversion of waste to energy and high value products. Microalgae biorefinery has numerous advantages over other biorefineries in a way that multiple products can be targeted ranging from energy to bioactive compounds, modest reactor designs for cultivation, utilisation of natural resources like sunlight, air, wastewater for growth and production, ambient operating conditions. Such diversity is not visible with other biorefineries, for example, lignocellulosic or sugarcane biorefinery which requires complex reactor designs, energy intensive pretreatment process, complex media composition, sterile conditions to avoid contamination and less diversity in products. Moreover, the microalgae residue left over after lipid or protein extraction is still a source of nutrients and can be channelled to produce biofuels and animal feed which makes it a waste-free biorefinery concept. However, the crucial stage in microalgae biorefinery is to minimise loss of product yields at each stage while separation of different fragments. Due to small size and low density of microalgae cultures, loss of biomass is critical at every step. This issue can be solved by employing scalable, low-cost and energy-efficient separation techniques. Microalgae biomass is a great raw material for biorefinery approach as it can yield multiple components suitable for various industries such as food, energy, pharmaceutical and nutraceutical industry thereby providing high flexibility towards changing markets. In this review, we have emphasised on use of wastewater as a source of nutrition for microalgae biomass production and utilising the biomass and lipid extracted biomass as a potential feedstock to produce multiple products thereby establishing an integrated microalgae biorefinery approach.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of various products derived from raw and delipidified microalgae

Microalgae biomass production and wastewater treatment

Wastewater as a nutritional source

Wastewater is a rich source of nutrients including minerals, metals and trace elements whose concentration varies with the sources. Improper disposal of wastewater from industries, agriculture, and municipal is a major source of pollution of water and soil. The pollutants in the form of heavy metals and other toxic elements pose a threat to the environment. Moreover, excessive nutrients present in wastewater in the form of nitrogen and phosphorus also results in eutrophication in lakes thereby disturbing the ecosystem. These serious environmental issues caused by wastewater has called for ways for proper utilisation and disposal of wastewater from different sources. Currently, conventional methods of wastewater treatment are widely used in industries to reduce the toxic levels of metals and nutrients prior to discharge or reuse (Gogate et al. 2004; Raza et al. 2018; Varjani et al. 2019). But these methods are not economical and environment friendly as it involves both chemical and physical processes to reduce the toxicity of wastewater. Various biological processes are also opted for wastewater treatment using different microbial flora which has the ability to utilise the nutrients and convert them into energy products like hydrogen, ethanol, biodiesel etc. (Machineni et al. 2019). Microalgae is one such flora which has the ability to utilise the nutrients of wastewater for its growth and metabolism (Table 1). Microalgae require large amounts of nitrogen and phosphorous for its growth and wastewater from various sources are rich in these elements (Li et al. 2019a, b). Therefore, efficient cultivation of microalgae acts as a promising tool for treatment of toxic effluents. Moreover, nitrogen and phosphorus present in wastewater helps to improve both quality and quantity of lipid accumulation in the microalgae cells. This lipids act as a raw material for biodiesel production. Economics of the biorefinery concept of microalga products does not fit well and operational cost is the major challenge. Utilization of wastewater as nutrient source for microalgae biomass production reduces a major part of the production cost, thereby making the biorefinery concept feasible (Nagarajan et al. 2020).

Table 1.

Types of wastewater used as nutritional

source for microalgae biomass production

| Sl. no. | Types of wastewater | Microalgae strain | Biomass productivity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dairy wastewater | Chlorella pyrenoidosa | 24.44 mg/L/day | Brar et al. 2019 |

| 2 | Agricultural wastewater |

Chlorella sp Scenedesmus sp. Rhizoclonium hieroglyphicum |

2.6 g/m2/day 10.7 g/m2/day 17.9 g/m2/day |

Gupta et al. 2019 |

| 3 | Industrial wastewater |

Micractinium sp. ME05 Arthrospira maxima |

320 mg/L/day 150 mg/L/day |

Montalvo et al. 2019 |

| 4 | Municipal wastewater |

Scenedesmus obliquus Scenedesmus dimorphus Chlorella vulgaris |

26 mg/L/day 22.7 g/m2/day 99.21 mg/L/day |

Novoveska et al. 2016 Lage et al. 2018 Xu et al. 2019 |

Nitrogen is used in its organic form as the building block of biological molecules such as proteins and lipids in all living organisms. The metabolic pathway of microalgae can utilise nitrogen in its inorganic form as nitrates, ammonia, nitrogen gas or nitric acid and converts them into its organic form by a process called assimilation (Akgul et al. 2020). Microalgae assimilates nitrate and nitrites which is then reduced to ammonium by biological catalysts nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase. Optimised carbon/nitrogen ratio has demonstrated higher biomass production of 5 g/L with increased lipid content up to 60.34% in microalgae Chlorococcum sp. (Khanra et al. 2020). Microalgae prefers ammonium over other inorganic sources as its assimilation requires less energy and can be incorporated into amino acids within the cells. This further corroborates that wastewater rich in ammonium can serve as a good source of nitrogen and can help in rapid production of microalgae biomass.

Phosphorus is another essential nutrient required for microalgae growth. Wastewater from different sources contains phosphorus as another major element. Phosphorus plays an important role in energy metabolism of microalgae and forms a major part of nucleotides, proteins and lipids (Zhuang et al. 2018). Mostly phosphorus intake occurs in the form of orthophosphate (PO42−) and gets incorporated into the cells to generate ATP (adenosine triphosphate) which acts as a driving force for many cellular reactions (Cai et al. 2013). Phosphorus also acts as a building block of nucleic acids (DNA, RNA) and thus helps in transmission of genetic information between generations. Thus, wastewater containing higher phosphorus can be a potential source of nutrient for microalgae growth.

Carbon is another important nutritional element for efficient growth and photosynthesis of microalgae. Intake of carbon source occurs in microalgae in the form of CO2 or soluble carbonates. CO2 can be easily fixed by microalgae from atmosphere through Calvin-Benson cycle and gets incorporated into the cells in the form of carbohydrates. Industrial gases or flue gas are the major sources of CO2 and thus microalgae act as a promising tool to reduce the CO2 emissions by utilising it for its growth and metabolism. Further, the presence of soluble carbonates (CaCO3, Na2CO3) or bicarbonates in wastewater can also be utilised by microalgal cells for its growth (Cai et al. 2013).

Other nutrients present in wastewater include microelements like iron, calcium and heavy metals. These micronutrients may be toxic to few species of microalgae at higher concentrations but there also exists few strains which are tolerant to heavy metals and other trace elements. Microelements play a major role in lipid accumulation and biomass productivity (Ghafari 2018). Therefore, based on the microalgae species used, the nutrient composition in the wastewater need to be maintained and optimised for efficient growth and production of biomass. In this section we have discussed various sources of wastewater which can be used as a nutritional source for microalgae cultivation. Further, we discuss the criteria for selection of strains capable to grow and utilise specific nutrients present in various wastewater and the preferred methods of cultivation and harvesting microalgae.

Agricultural wastewater

India being an agricultural country, generates large volume of wastewater from agricultural lands and farms. A major part of this stream of wastewater consists of surface runoff from fields which may contain fertilizers, chemicals, animal manure, soil minerals and crop residues. Fertilisers and manure contain nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium as the major elements hence agricultural wastewater contains these nutrients in higher concentration (Wollman et al. 2019). Presence of these elements in agro wastewater supports the growth of microalgae along with removal of toxic molecules (Gupta et al. 2019). Farms with poultry and livestock operations generate wastewater rich in organic content as well as NPK and ammonia. Apart from these beneficial nutrients it also contains many harmful pesticides, chemicals and toxic metals which may inhibit the microalgae growth at higher concentrations. Therefore, agro wastewater may require few pretreatment or purification steps prior to be used as a source of nutrition for microalgae biomass production.

Industrial wastewater

The nutritional composition of industrial wastewater varies based on their product and processing technology. Industrial effluents contain both nutritional and toxic elements in varied concentrations depending on the source of origin. Industries like leather, pharmaceutical, beverage, oil drilling, textile dyeing, detergent and confectionaries contribute much to urban wastewater generation. These wastewater contains potassium, sodium, sulphur and nitrogen as the major elements which could be beneficially sourced towards algae biomass production. Various authors reported efficient phycoremediation strategies for various industrial effluents by using green algae (Saranya et al. 2020; Almeida et al. 2020; Sharma et al. 2020). Leather processing industries are involved in manufacturing of dyes, pigments, binders and also use various chemicals, heavy metals for processing leathers which finally flows into effluents. Physico-chemical characterisation of this effluent revealed the presence of calcium, magnesium, potassium, ammonia, chloride, sulphate and phosphate as major elements. Chlorella vulgaris was used for treatment of leather processing effluent and it grew luxuriantly with a biomass production of 1 g/L dry weight and utilised almost 99% of the phosphates and 71% of the sulphates contained in the effluent. (Sivasubramanium 2016). Chlorella vulgaris resulted in removal of 84.68% and 98% of nitrogen and phosphorus respectively, from MnO2 industry effluent (Li et al. 2019a, b). Similarly, confectionary industry effluents are nutritious source for microalgae growth since it contains enormous amounts of sugars, sweeteners, casein, condensed milk along with food colours, gums, flavours which all together becomes a part of the effluent. Effluent from a confectionary industry located in Chennai, India was used for growing microalgae cells of Chlorella vulgaris which showed high biomass productivity of 1.5 g/L. Another species of microalgae Chlorococcum humicola grew luxuriantly with algal biomass reaching 4.8 g/L. Microalgae grown on confectionery industrial effluent also resulted in increased production of proteins and lipids within the cells, thereby suggesting as an efficient nutrient source for microalgal lipid production.

Textile industry effluents are highly alkaline and contain various dyes and chemicals like sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride, sulphate, phosphates etc. Sivasubramanium, 2016 utilised wastewater from two textile dyeing industries located in Chennai and Ahmedabad for growing microalgae species such as Chlorococcum humicola, Chroococcus turgidus and Desmococcus olivaceous. These cells grew well in the effluent utilising 89% of iron, calcium, magnesium and 46% of phosphate from the raw effluent thereby producing 0.75 g/L of algal biomass. Among all strains used, Chlorococcum humicola grew very well in the textile effluents. FAME analysis of oil extracted from this algal biomasss supports the existence of saturated fatty acids Heneicosanoic acid methyl ester (C21:0) and Arachidic acide methyl ester (C20:0) as major components, indicating that it is highly suitable for biodiesel production.

Dairy industrial wastewater generated from various processing streams is high in contaminants and also in nutrients whose improper discharge without treatment may not only lead to pollution but also may cause serious environmental issues like eutrophication of water bodies. India is the largest producer of milk in the world with 187.7 million tons of milk produced during 2018–2019. It is estimated that processing of each litre of milk generated about 1–1.5 L of dairy effluent which amounts to 300–450 lakh litres of effluent per day generated due to cleaning of containers and other processing activities. Effluents from dairy industries are a rich source of protein, phosphorus, nitrogen and high in organic matter with COD ranging from 1000 to 7000 mg/L. Dairy wastewater can thus serve as nutrient source for microalgae growth thereby leading to bioremediation of wastewater. Treatment of dairy wastewater using microalgae will not only generate clean water but also produce algae biomass which acts as a sustainable feedstock for production of third generation biofuels and value added products. Recently, several authors have evaluated various microalgae strains for dairy wastewater treatment (Hena et al. 2015; Lu et al. 2015; Qin et al. 2016). Huo et al. (2012) cultivated Chlorella zongfingensis strain in dairy wastewater which resulted in 97.5 and 51.7% removal of total nitrogen and total phosphorus in 5 days. Similarly, Ding et al. (2014) reported removal of 89% COD, 91% phosphorus and 99% nitrogen from dairy effluent by microalgae cultivation. Cultivation of Chlorella sp. in raw dairy wastewater resulted in maximum biomass productivity of 110 mg/L/day in outdoor pilot-scale plant (Lu et al. 2015). Lipids extracted from it is highly rich in C16/C18 fatty acids showing high potential for production of biodiesel. Kumar and co-authors have evaluated both indoor and outdoor cultivation of microalga Ascochloris sp. ADW007 in dairy wastewater for simultaneous removal of nutrients along with lipids and high biomass productivity (Kumar et al. 2018a, b).

Municipal wastewater

Municipal wastewater (MW) which mainly originates from public usage have different characteristics as compared to other industrial wastewater and is a major source of pollution of water bodies. Most of the MW originates from public homes, hospitals, corporates and other community places and contains toxic chemical contaminants along with sewage matter. It is characterised by low COD and imbalanced nitrogen-phosphorus ratio as compared to other industrial effluent and hence considered as a weak medium for the cultivation of microalgae. Currently used biological methods for MW treatment includes trickling filters, aerated lagoons, activated sludge system and anaerobic processes can effectively remove biodegradable organic pollutants but removal of inorganic nutrients such as phosphorous, nitrogen is usually inadequate. Presence of nitrogen as ammonia and nitrate salts and phosphorus as phosphates in MW can act as nutrient source for microalgal blooms which can be further channelled to produce biofuel, lipids and other biobased products. The major challenge with microalgae-based MW treatment is the presence of excessive solid matter in the form of sewage or human waste which may help in the proliferation of other microbes like bacteria and protozoa and may also contain pathogenic microbes. Protozoa act as predators for microalgae and thus may inhibit its growth in municipal wastewater. This problem can be resolved by pre-treatment of MW prior to microalgae cultivation like filtration, heat shock and UV treatment (Cho et al. 2011). Cho et al. suggested that filtration of MW through 0.2 µm membrane prior to microalgae cultivation resulted in maximum biomass (0.67 g/L) and lipid productivity (22.9 mg fatty acids/L/day) with simultaneous removal of 92% total nitrogen and 86% of total phosphates.

Various other researchers have also studied microalgae cultivation for nitrogen and phosphorus removal in municipal wastewater (Aketo et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2019).

Criteria for strain selection

Microalgae differ significantly based on the cellular contents, growth behaviour and metabolic pathways for target products. Therefore, it is very important to select the right strain that best fit the process and products targeted for the biorefinery concept. The strain to be used in a biorefinery concept acts as a cell factory capable of producing various products through different metabolic pathways within a single cell. Growth rate, oil productivity, optimal growth conditions and scale-up potential are few specific parameters to be considered for selection of microalgal strain (Leu and Boussiba 2014). Further, tolerance to environmental stress conditions such as pH, temperature, oxygen and toxic chemicals such as heavy metals are the most important characteristics to be considered for microalgae cultivation in wastewater (Chisti 2007). In the following section, microalgal strains which have the ability to grow under harsh operational conditions with high lipid productivity and also produce generous amounts of proteins and pigments, would be focussed.

Lipid producing strains

With a view to develop a microalgal biorefinery with biodiesel as the main product, the most important criteria to be considered for selection of microalgae strains is high lipid content. Lipids are accumulated in the form of droplets within the microalgae cells and its production is affected by various environmental factors such a light, pH, CO2, salinity, nutrient and metal stress, availability of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. Literature provides numerous reports supporting increased lipid accumulation under abiotic stress conditions such as deprivation of nitrogen or phosphorus, high intensity of light, increased CO2. Lipid production ability of microalgae is determined by few quantitative parameters viz., lipid productivity, lipid yield, lipid content and biomass productivity. Heterptrophic Chlorella protothecoides has been reported to be one of the highest lipid and biomass producer with lipid productivity of 1.2–3.7 g/L/day and biomass productivity of 2.2–7.4 g/L/day. On the other hand, mixotrophic Chlorella vulgaris is reported with a lipid productivity of 22.0–54.0 mg/L/day when grown in sunlight with glucose and glycerol as carbon sources (Chen et al. 2011). Several studies have also reported algal biomass and lipid production by using dairy, domestic and urban effluents, although the production varied with different species and source of wastewater. Cultivation of Botryococcus braunii in domestic wastewater resulted in biomass productivity of 0.28 g/L/day and lipid content reached upto 25% of dry weight. On the other hand, the same species cultivated in synthetic medium resulted in reduction of biomass productivity (0.22 g/L/day) and increased in lipid content upto 47% of dry weight. Use of urban wastewater for cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris showed higher lipid productivity (14.31 mg/L/day) as compared to synthetic medium (Singh et al. 2017). Dairy wastewater serves as one of the best nutrient source for microalgal growth with biomass productivity of 0.11 g/L/day in Chlorella sp. and 0.207 g/L/day in Ascochloris sp. (Lu et al. 2015; Kumar et al. 2019). The lipid content in Ascochloris sp. grown in raw dairy wastewater reached upto 34.98% of dry weight. The lipid molecules produced by these species are tri-acyl glycerol (TAG) which acts as an excellent feedstock for biodiesel production.

However, few species of microalgae produce long chain poly unsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) which include omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. These fatty acids have essential nutritional benefits on human health and is produced by many species such as Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Nannochloropsis sp., Parietochloris incise and Thalassiosira sp. (Leu and Boussiba 2014). Other high value fatty acids such as eicosapentaenoic (EPA), γ-linolenic, docosahexaenoic acids (DHA) and arachidonic are also produced by few microalgae strains which can be extracted and used as pure nutritional supplements (Brennan and Owende 2010; Yen et al. 2013; Cuellar-Bermudez et al. 2015).

Carbohydrate producing strains

Carbohydrates accumulated in microalgal cells can be either used for bioethanol production or directly as food supplements or in cosmetic and textile industries as thickening agents, emulsifiers and stabilisers. Porphyridium cruentum is widely used as a commercial strain in cosmetic industry as it hoards large amount of extracellular carbohydrates (Leu and Boussiba 2014). These polysaccharides are also used as antioxidant, antitumor, anticoagulant, antiinflammatory, antiviral, and immunomodulating agents (Yen et al. 2013; Grimm et al. 2015; Rodriguez- Zavala et al. 2010).

Pigment producing strains

Pigments derived from microalgae include chlorophyll, phycobiliproteins and carotenoids which are high value products with enormous demand in pharma and food markets. Chlorophyll is the most common and widely available microalgae pigment which has found its way in various medical treatments such as ulcer treatment, anaemia treatment by increasing the haemoglobin level in blood and also used as chelating agent in ointments (Harun et al. 2010). Pigment pheophorbide A, derived from chlorophyll is being used for cancer treatment in humans like uterine sarcoma (Yen et al. 2013). The red carotenoid astaxanthin, derived from Haematococcus pluvialis, is known for its antioxidant properties and is currently marketed as a nutraceutical with a market potential of $200 million (Koller et al. 2014). Phycobiliproteins are well known for its high fluorescence and nonspecific binding properties due to which it finds wide application in biotechnology research as detection tools (Yen et al. 2013; Cuellar-Bermudez et al. 2015). R-phycoerythrin is a negatively charged highly fluorescent red protein which has wide applicability in fluorescence-based assays and currently marketed by Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. for $105.50/mg (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. 2009, 2015; Cuellar-Bermudez et al. 2015).

Microalgae cultivation and harvesting

In comparison to other energy crops, microalgae can grow much rapidly due to higher photosynthetic efficiency. Microalgae cultivation has numerous advantages over other oil- producing crops viz., (i) Suitable candidate for industrial raw material as it can accumulate various bioactive compounds, (ii) Cultivable in non-arable land. No requirement of fertile land, pesticides, freshwater, (iii) Cultivable in wastewater. No nutrients or fertiliser required, (iv) Mitigation of greenhouse gases. Utilises CO2 for photosynthesis, (v) Higher photosynthesis rate hence grows rapidly with short life cycle.

In spite of these benefits, microalgae have not gained much attention as a raw material for production of fuel and other high value compounds. This is mainly due to low biomass productivity and additional operating costs for harvesting techniques. These problems can be compensated by increasing the growth rate or production capacity along with economical harvesting techniques. An ideal microalgae cultivation system must satisfy the following factors (i) adequate light intensity (ii) simple operating system (iii) minimal contamination (iv) cheap cultivation configuration with high production efficiency (v) efficient vertical use of land. Microalgae cultivation system can be classified as open system and closed system. Open system includes raceway ponds and V-ponds whereas closed systems includes photobioreactors (tubular and flat plate). Table 2 provides a comparative comparison of all types of cultivation systems.

Table 2.

Comparison of various microalgae cultivation and harvesting methods

| Sl. no. | Process | Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Microalgae cultivation | Raceway ponds | Relatively cheap, easy to clean, utilise non agriculture land, low energy inputs, easy maintenance | Poor biomass productivity, large area of land required, limited to a few strains of algae, poor mixing, cultures are easily contaminated |

| V-shaped ponds | Easy to construct, easy to operate, cheap, low production cost for algae biomass | Poor light utilisation through cell, evaporative losses, require a large area, poor diffusion of CO2 from the atmosphere | ||

| Flat plate photobioreactor | High biomass productivity, easy to sterilise, low oxygen build-up, good light path, large illumination surface area, suitable for outdoor cultures |

Difficult to scale-up, difficult for temperature control, small degree of hydrodynamic stress, some degree of wall growth |

||

| Column photobioreactor | Compact, high mass transfer, low energy consumption, good mixing with low shear stress, easy to sterilise, reduced photo-inhibition and photo-oxidation | Small illumination area, expensive compared to open ponds, shear stress | ||

| Tubular photobioreactor | Large illumination surface area, suitable for outdoor cultures, relatively cheap, good biomass productivities | Some degree of wall growth fouling, requires large land space, gradients of pH, accumulation of dissolved oxygen and CO2 along the tubes | ||

| 2 | Harvesting | Flocculation | Wide range of flocculants available, price varies although can be low cost | Removal of flocculants, chemical contamination and toxicity |

| Filtration | Wide variety of filter and membrane types available | Highly dependent on algal species, best suited to large algal cells, clogging or fouling an issue | ||

| Centrifugation | Can handle most algal types with rapid efficient cell harvesting | High capital and operational costs | ||

| Flotation | Can be more rapid than sedimentation, possibility to combine with gaseous transfer | Algal species specific, high capital and operational cost |

Open systems

Raceway ponds are one of the most common and oldest method of cultivation for large scale production of microalgae biomass. It is generally oval-shaped closed loop structure made of concrete or plastic. CO2 is spurged from bottom to achieve proper mixing and high rate of photosynthesis (Fig. 2a). The system also contains paddlewheels at regular intervals to prevent sedimentation of biomass. This system is widely preferred because of low maintenance, low energy input and low cost of construction. Average investment cost for construction of open raceway systems ranges from 0.13 to 0.37 million euros/ha at 100 ha scale which is equivalent to 1.1 to 3.2 crores INR/ha (Chisti 2012; Norsker et al. 2011). The capacity of these reactors at industrial scale ranges from 1000 to 5000 m2 and maximum biomass productivity of 40 g/m2/day has been reported which is equivalent to 150 ton/ha2/year (Lundquist et al. 2010). Although biomass productivity varies with strain, type of water, salinity, pH and climatic conditions. For example, microalagal strain Tetraselmis suecica reported biomass productivity of up to 9 g/m2/day whereas cultivation of Nannochloropsis sp. resulted in biomass productivity of 15 g/m2/day (Chiaramonti et al. 2013).

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of standard open photobioreactors used for microalgae cultivation a Open Raceway Pond b V-shaped Pond

V-shaped pond is another open system used for microalgae cultivation which is economical and efficient as compared to open raceway ponds. It is in the shape of an inverted pyramid providing maximum surface area to the microalgae cells for efficient light absorption. Kumar et al. 2020 designed a high volume V-shape pond (HVVP) with a capacity of 3000 L which was concluded as one of the most economical system for microalgae cultivation (Fig. 2b). This type of reactor was advantageous due to low cost of fabrication consisting of structures made of mild steel (MS) and polyvinyl sheets. Due to conical shape it also occupies less land surface reducing the total operational cost of cultivation.

Closed systems

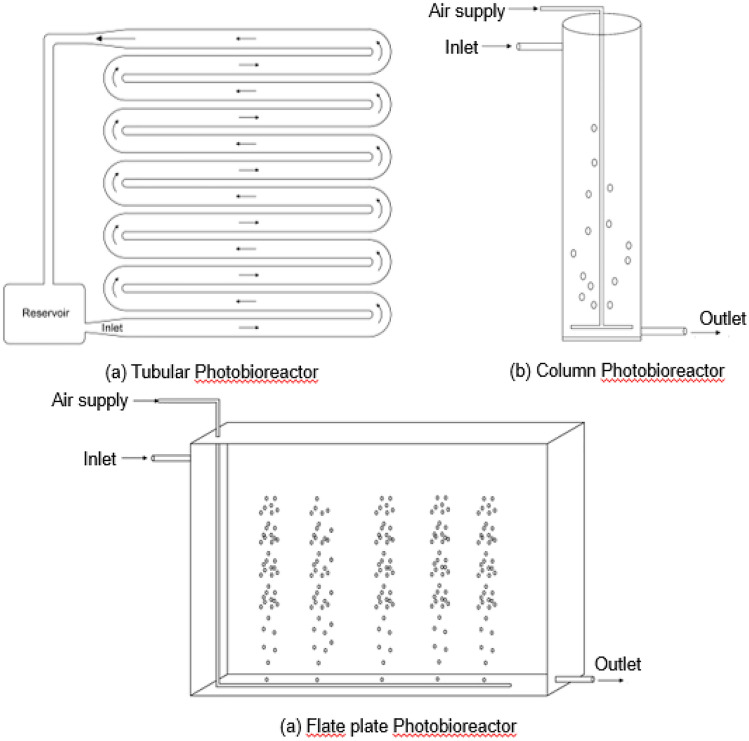

Closed systems of microalgae cultivation includes photobioreactors (PBRs) in the form of tubular, column or flat plate reactors. These are enclosed systems with no direct exchange of material between culture and environment. As compared to open systems, PBRs are compact reactors with highly controlled growth conditions which reduces contamination and also enhance biomass productivity.

Tubular PBR consist of long transparent glass or plastic tubes arranged vertically or horizontally through which culture is circulated continuously for maximum exposure to light (Fig. 3a). This system has constraints like O2 accumulation, sedimentation of culture and poor mass transfer which reduces its efficiency.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of standard closed photobioreactors (PBR) used for microalgae cultivation a Tubular PBR b Column PBR c Flate plate PBR

Vertical column PBR consist of a single cylindrical column made of plastic equipped with a spurger which pumps air for proper mixing and CO2 transfer into the culture (Fig. 3b). This system provides best gas–liquid mass transfer and simple operation with low energy demand. However, it is not a preferred system for large scale production due to inadequate light exposure to microalgae cells due to the cylindrical shape and difficulties in cleaning the reactor.

Flat plate PBR is a modified version of column PBR which is redesigned to minimise the constrains of column PBR. The rectangular shape of this reactor provides largest surface area for adequate light capture and low O2 accumulation thereby increasing rate of photosynthesis (Fig. 3c). Various innovative design has been implemented to further improve its efficiency for commercial usage.

Algenol Biotech LLC has developed a pilot scale facility using polyethylene bags as flat plate reactors across 36 acres with a productivity of 8000 gallons of ethanol/acre/year (Algenol Biotech LLC 2011). Another company named Joule Unlimited Inc. have reported production of 25,000 gal/acre/year of ethanol and 15,000 gal/acre/year of biodiesel using pilot plant of flat plate PBR (Lane 2015).

Two stage hybrid system is an advanced form of microalgae cultivation where two types of separate reactors are combined for high biomass productivity and maximum lipid accumulation. The hybrid system integrates airlift tubular photobioreactors for continuous growth of microalgae cells and open raceway ponds which promotes high lipid accumulation under nutrient deficient conditions. This type of cultivation not only results in high productivity but also reduces contamination issues. Narala and co-authors have studied and compared hybrid system with open raceway and tubular PBR and found it to be more superior in terms of high lipid production (Narala et al. 2016). Moreover, a life cycle assessment of a hybrid cultivation system using Chlorella vugaris showed 38% savings in fossil-energy requirements and 42% savings in global warming potential (Adesanya et al. 2014).

Microalgae harvesting

Harvesting techniques are used to separate microalgae biomass from culture media to facilitate extraction of energy and other value added products from biomass. Harvesting step accounts for 30% of total production cost due to energy demand and manpower requirement. Various harvesting methods have been implemented for concentration of microalgae biomass such as filtration, flocculation and centrifugation.

Filtration is the simplest method of harvesting which utilise a semipermeable membrane with varied pore size that percolates water or culture medium thereby retaining microalgae biomass. This system requires no power input and can be used for large scale but it encounters problems like clogging and fouling which demands frequent change of filter membranes. This adds up to the processing cost. Use of cheap filter membranes can help to overcome this problem.

Centrifugation is the most efficient and rapid method of harvesting as it removes water completely from biomass within fraction of time. But it is highly energy intensive and requires high power input which adds up to the production cost.

Flocculation is another method for harvesting microalgae cells which uses flocculating agents to aggregate the cells together to form floc. Chemical flocculants such as iron and aluminum salts remove the surface charge of cells and results in precipitation of algal biomass. Flocculants like iron chloride and aluminum sulphate can flocculate 95% of microalgae biomass (Chatsungnoen et al. 2019). But these chemicals are toxic to nature and the removal process further ads to the cost of production. An alternative to this is the use of organic flocculants such as chitosan, acrylic acid which are eco-friendly and safer to use. Chitosan has been reported to aggregate 90% of microalgae biomass at much lower dose as compared to chemical flocculants.

Although centrifugation and filtration are currently used methods to harvest microalgae at industrial scale, but recently flocculation have received much attention as researchers have found many opportunities to advance this method of harvesting. Use of magnetic nanoparticles as flocculant has an advantage over conventional methods in terms of separation time and harvesting efficiency (Khanra et al. 2020; Matter et al. 2019). Iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles when used to harvest microalgae cultures of B. braunii, with a dose of 55.9 mg cell/mg particles resulted in 98% harvesting efficiency in 1 min. Similarly, iron oxide embedded carbon microparticle was used at a dose of 25 g/L, 99% harvesting efficiency was obtained in 1 min (Matter et al. 2019). Another approach was claimed by Origin Oil Inc. where electromagnetic pulse is used to induce sedimentation of microalgae cells by neutralising the surface charges.

Recently, research has also been focussed towards more advanced form of flocculation techniques by genetic modification. Genetically engineered yeast has been applied as flocculants which has the ability to express extracellular proteins called flocculins on the cell surface which attach to the microalgae cells promoting aggregation (Matter et al. 2019). Similarly, ligand-receptor mechanisms have been explored to enable fast and targeted aggregation, where microbes expressing an antibody could be mixed with cells expressing the specific antigen thereby inducing flocculation.

Multi-product biorefinery approach

Although significant research is going on in the area of algal bioenergy, but due to higher energy requirement and time consuming processes of cell culturing, harvesting and conversion the algal biofuel is unable to compete in open market (Grima et al. 2003). A microalgal biorefinery concept combining all stages of algal cultivation with conversion of lipid to biofuel and other allied products is an attractive approach to make algal products commercially viable. Advanced bioreactor design and development of new technologies for harvesting, dewatering and oil extraction can make the algal bioenergy feasible and competent in market. Microalgae is a rich source of proteins, carbohydrates and lipids and hence can act as a feedstock for production of diverse products which includes biofuels (biodiesel, biohydrogen, biomethane, bioethanol) and value added products such as protein, pigment, antioxidants (Table 3).

Table 3.

List of microalgae derived products and co-products

| Sl. no. | Products | Co-products | Strain | Yield | Productivity | Applications/advantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Biofuel | Biodiesel |

Chlorella pyrenoidosa Botryococcus sp. |

95.1% 88% |

1.44 g/g/h 0.22 g/g/h |

Biodiesel is better than diesel fuel in terms of sulphur content, flash point, aromatic content, and bio-degradability Biodiesel is an environmentally friendly alternative liquid fuel that can be used in any diesel engine without modification Job creation for the local population, provision of modern energy carriers to rural communities |

Sivaramakrishnan and Incharoensakdi (2017) |

| Bioethanol |

Chlamydomonas sp. KNM0029C Scenedesmus raciborskii WZKMT |

0.22 g/g biomass 79.38 g/L |

0.22 g/g/day 0.66 g/L/h |

Biomethanol as a renewable fuel. Bioethanol fuel reduces lead, sulphur, CO, and particulate emissions 20% blending of bioethanol with gasoline is acceptable |

Alam et al. (2019) |

||

| Biohydrogen |

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides Botryococcus braunii Chlorella vulgaris/ Spirulina |

40% v/v 45% v/v 64% v/v 70–75% v/v |

Cleanest biofuel, only water as by-product High energy content as compared to gasoline |

Hemschemeier et al. (2008) | |||

| 2 | Lipids | Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) |

Cocculinella minutissima Monodus subterraneus Phaeodactylum tricornutum |

36.7 mg/L 96.3 mg/L 43.4 mg/L |

EPA is most commonly used for heart disease, preventing adverse events after a heart attack, de-pression, and menopause | McKinlay et al. (2010) | |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) |

B. carterae Crypthecodinium cohnii Nannochloropsis oculata |

8.6 mg/L 19.5 mg/L 2.6 mg/L |

Reduce inflammation and your risk of chronic diseases, such as heart disease DHA supports brain function and eye health |

||||

| 3 | Pigments | Lutein |

Haematococcus pluvialis Chlorella sorokiniana MB-1 |

7.15 mg/g dry weight 5.21 mg/g |

10.83 mg/g/h 5.78 mg/L/day |

Lutein is another promising candidate in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and nutraceutical formulations. It can filter blue light (high-energy photons) from the visible light spectrum and can scavenge free radicals generated from biochemical reactions after lipid peroxidation |

Molino et al. (2018); Chen et al. (2016) |

| β-carotene |

Dunaliella salina Nannochloropsis gaditana |

32 mg/L 100.1 |

4.57 mg/L/day |

β-carotene can stimulate the immune system, supplement for diseases including cancer, coronary heart diseases, premature ageing, and arthritis β-carotene prevents cataracts, night blindness, and skin diseases Used as food colourants to improve the appearance of margarine, cheese, fruit juices, baked goods, dairy products Prevention of oxidation of low density protein that can be applied to prevent arteriosclerosis, coronary heart disease, and ischemic brain development |

Xi et al. (2020) | ||

| Astaxanthin | Haematococcus pluvialis | 18.5 mg/g dry weight | 13.9 mg/g/h |

Dietary administration of astaxanthin has proven to inhibit carcinogenesis in the mouse urinary bladder, rat oral cavity, and rat colon Astaxanthin has the ability to induce xenobiotic metabolising enzymes in rat liver Antioxidant property Protection against excessive sunlight Used in the respiratory mechanism of protoplasm |

Molino et al. (2018) | ||

| Xanthophyll |

Scenedesmu almeriensis Synechococcus sp. Chlorella vulgaris Nannochloropsis gaditana |

20.0 mg/L 1510 mg/L 80 mg/L 25 mg/L |

Macias-Sanchez et al. (2005); Macias-Sanchez et al. (2010) | ||||

| Chlorophyll | Spirulina platensis | 0.9 mg/L |

Chlorophyll is an essential compound not only used as an additive in pharmaceutical but also used in cosmetic product Chlorophyll a has been extensively used as a colouring agent because of its stability Chlorophyll compounds usually have medicinal application because of their wound-healing and anti-inflammatory properties |

Chauhan and Pathak (2010) | |||

| 4 | Proteins | Phycobiliproteins | Anabaena NCCU-9 | 124.9 mg/g |

Phycobiliproteins are used in fluorescent labelling, flow cytometry, fluorescent microscopy, and fluorescent immunohistochemistry Used as natural dye in food and cosmectics, with phycocyanin in particular used as a blue pigment used in products such as chewing gum, popsicles, confectionary, soft drinks, dairy products, and wasabi, as well as cosmetic products, such as lipstick and eyeliner Nutraceutical applications such as anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-viral, anti-tumour, neuroprotective, and hepatoprotective activities Used as animal feed |

Hemlata and Fatma, (2009); Silveira et al. (2007); Chaneva et al. (2007) | |

| Phycocyanin |

Spirulina platensis Arthronema africanum |

0.0036 mg/L 0.23 mg/L |

0.0009 mg/L/h | ||||

| 5 | Vitamins | Thiamine | Tetraselmis suecica | 493–750 mg |

Used as food supplements Used as drug supplements to treat diseases including malnutrition |

Safafar et al. (2015) | |

| Riboflavin | Dunaliella tertiolecta | 31.2 mg | |||||

| a-tocopherol | Chlorella stigmatophora | 669 µg/g |

Products from microalgae

Microalgae acts as a cell factory producing diverse products ranging from lipids to small bioactive compounds. Microalgal lipids such as triglyceride, glycolipids, phospholipids act as precursors of biodiesel, omega-3, decosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentanoic acid (EPA), respectively. Microalgae are rich sources of food and neutraceutical products to fight against malnutrition around the globe. The microalgal bioactive compounds have wide applicability in pharmaceutical industries for synthesis of anticarcinogenic molecules, antioxidants and antihypertensive agents (Krishna 2019). Microalgae can be utilised to extract essential amino acids, proteins, pro-vitamins and vitamins.

Lipids

Extraction of lipids: Microalgal lipid extraction methods can be categorised as chemical and mechanical methods. Chemical process of lipid extraction includes organic solvents (chloroform, methanol, hexane), supercritical CO2 and ionic solvent extraction. On the other hand, mechanical methods of extraction involves the application of microwave, ultrasonic waves, bead beating and oil expeller (Halim et al. 2011).

-

(A)Chemical methods for lipid extraction

- Solvent extraction method: The microalgal lipid can be extracted using polar and non-polar solvents. The principle behind the solvent extraction of lipid is based on the concept of basic chemistry “like dissolves like”. The non-polar solvents are combined with polar solvents to maximise the lipid yield. The most commonly used method for lipid extraction is the Bligh and Dyer (1959) method which is a modification of Folch method (Bligh and Dyer 1959). This method utilised a mixture of chloroform and methanol in a ratio of 1:1 or 1:2 (v/v) to extract lipids from homogenised microalgae biomass. The lipids get accumulated in the upper chloroform phase while proteins are precipitated at the interphase of the two solvents. The chloroform is recovered using fractional distillation which can be reused for the next batch. Another approach for solvent based lipid extraction is the soxhlet extraction using single or a mixture of solvents like hexane, ethyl acetate, ethyl lactate, 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF), cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) in a soxhlet apparatus (Mahmood et al. 2017). The authors in this study reported that lipid extraction by renewable bio-based solvents was more efficient as compared to petroleum derived solvents like hexane. The solvent polarity plays a key role in the lipid extraction process. The combination of polar and non- polar solvents improves the efficiency of lipid extraction as the polar solvents can penetrate cell wall and making intracellular non polar lipids available to the non-polar solvents (Li et al. 2014).

- Supercritical CO2 extraction: The super critical solvent extraction generally uses CO2 as solvent under varied extraction pressure and temperature and yields solvent free crude lipid (Taher et al. 2014). Tang et al. (2011) reported yield of 33.9% of lipids extracted from Schizochytrium limacinum using supercritical CO2 and under the optimum conditions of temperature 40 °C and pressure 35 MPa. Optimization of the parameters of supercritical CO2 extraction process is essential as it affects the yield of lipid extraction which varies among different microalgae strains.

- Ionic solvent extraction: Ionic liquids (ILs) are salt solutions containing an organic cation and an inorganic anion which are liquid at temperature range of 0–140 °C. ILs are non-flammable and have no detectable vapour pressure which makes them pollution free (Kumar et al. 2017). The ionic solvent/liquid extractions are favourable method for the extraction of microalgal lipid because of their non-volatility and thermal stability. Ionic liquid-methanol mixture shows the higher extraction efficiency. The dipolarity of the ionic liquid impacts the extraction yield and serves as green solvent for the lipid extraction from microalgal lipid (Kim et al. 2012). Salvo et al. (2011) has reported a single step process of lipid extraction using IL 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium which lyse the microalgal cells forming an upper hydrophobic lipid phase. Hydrogen bond acidity and polarity of ILs are the key parameters that need to be considered for efficient lipid extraction from microalgae (Kim et al. 2012). The solvent free method such as supercritical CO2 extraction might be clean and promising approach for more yield of lipid but remain at the laboratory scale. The solvent extraction methods are used commercially with comparatively higher yield of lipid than mechanical methods (Kumar et al. 2015).

-

(B)Mechanical methods of lipid extraction

- Bead Milling: This method utilised small glass beads with agitation to disrupt the cell microalgae cell membranes. The friction and collision generated between the beads shear the outer membrane of microalgae cells thereby extracting intracellular lipids and other compounds. The efficiency of this method depends on bead size, biomass concentration, temperature, agitation speed and time (Roux et al. 2017). Bead milling is considered as the most efficient membrane disruption technique but it is highly energy intensive and hence challenging to scale up (Dong et al. 2016).

- Ultrasound assisted extraction: This method utilised ultrasonic waves ranging from 20 to 50 kHz, which damage the cells and allows mass transfer to the external system, supporting extraction of lipids. Mostly horn and bath sonicators are used to disrupt cells by ultrasound. Ultrasound waves can disrupt cell structure by two mechanisms viz., cavitation and acoustic streaming. Cavitation is the growth and collapse of microbubbles caused by alternate cycle of high and low pressure during sonication of liquid cultures while acoustic streaming accelerates proper mixing (Khanal et al. 2007). Localised heat shocks are generated by transient cavitation which creates pressure on cells to rupture the outer membrane (Brujan et al. 2001). The process of ultra-sound assisted lipid extraction proves to be less time consuming and generates relatively low temperatures as compared to microwave or autoclave assisted extraction processes, thereby preventing thermal denaturation of bioactive molecules (Kumar et al. 2015).

- Microwave assisted extraction: Microwave assisted extraction of lipids was first reported in 1980s from seed, soil and food (Ganzler et al. 1986) and was found to be more efficient and economical than other conventional methods. Microwaves are electromagnetic radiation of frequency from 0.3 to 300 GHz which can generate intracellular heat and pressure resulting in formation of water vapour within the cells. This in turn results in electroporation effect which breaks cell membrane rendering efficient extraction of intracellular compounds from microalgae cells (Amarni et al. 2010). The microwave assisted heating uses a non-contact heat source, which can penetrate into the biomaterials, interact with polar molecules like water in the biomass, and heat the whole sample uniformly. The co-solvent system of ethanol and chloroform can be used for the extraction of lipids mediated by microwave.

Biodiesel

Microalgae is categorised as 3rd generation feedstock for biodiesel production. As compared to other energy crops, microalgae have higher growth rate, high lipid content and can be cultivated in non-arable land. These advantages have attracted microalgae as the most potential feedstock for biodiesel in recent times. The methods of conversion of lipid or oil into biodiesel can be categorised as esterification, transesterification and interesterification (Sandoval et al. 2017).

Esterification: Non-edible oils, waste cooking oil and animal fats are some of the biodiesel feedstock which contain high free fatty acid (FFA) content. FFA content can be quantified by titration based methods where oils are hydrolyzed by solvents (ethanol/diethyl ether) and titrated against alcoholic KOH solution. The value is expressed as % fatty acids or as acid number (mg KOH/g). Individual FFA can also be determined by gas or liquid chromatography after its conversion to methyl esters. These FFA can be converted to esters by esterification reaction in the presence of methanol and strong acid catalyst as shown below. The esters thus formed can be subsequently used to produce biodiesel (fatty acid methyl ester) by alkaline transesterification process (Mathimani et al. 2015).

Transesterification: This is the most commonly and widely used process for biodiesel production. Transesterification reaction basically converts high molecular weight triglycerides into three molecules of esters and glycerol in the presence of excess alcohol and catalyst (acid or base). It is a series of reaction where one ester is transformed into another by the interchange of the alkoxy moiety. This reaction is reversible; hence addition of excess alcohol is required to shift the reaction equilibrium towards product side. Due to low cost and higher reactivity, methanol is preferred for this reaction but other alcohols such as ethanol, propanol, amyl alcohol, butanol also shows good reactivity. Microalgae lipids consist of triglyceride chains which undergoes transesterification reaction in three steps, yielding di-glyceride in first step, followed by formation of mono-glyceride in second step and subsequently forming fatty acid methyl ester as the final product and glycerol as the byproduct in third step (Thao et al. 2013; El-Sheekh et al. 2016).The overall reaction can be represented as:

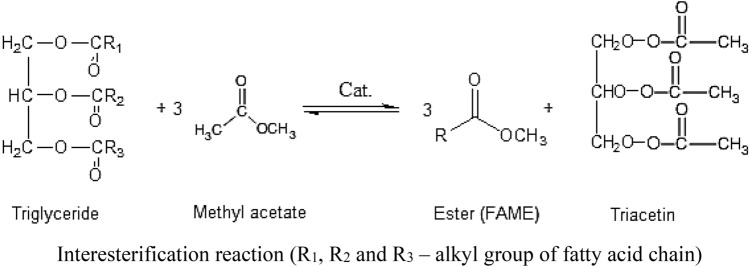

Interesterification: Interesterification is an alternative route of biodiesel production which occurs in the presence of simple esters such as methyl acetate instead of methanol. Fatty acid methyl ester (biodiesel) is the main product of this reaction along with the by-product triacetin. Triacetin acts as a blending agent in fuel with several other applications which increases its market value as compared to glycerol. Investigators found that 20% blending of triacetin to biodiesel is favourable for present IC engines. This makes overall interesterification process economically attractive and viable as compared to transesterification process. The overall interesterification reaction can be represented as:

The conversion of lipids to the biodiesel is affected by the reaction parameter such as alcohol: lipid ratio, reaction time and temperature, stirring and catalyst conversion. Increase in the alcohol volume enhances the yield of the biodiesel. Similarly, the reaction temperature and time remains directly proportional to the biodiesel yield. The catalyst such as strong acid (H2SO4) drives the reaction forward and increase the rate of reaction (Thao et al. 2013; Cao et al. 2013). The choice of catalyst is based on the free fatty acid (FFA) content of the lipid. The recovery of biodiesel is an important step after the transesterification. The biodiesel produced can be dissolved in hexane whereas glycerol is miscible in water, thus the addition of hexane and water to the reaction mixture forms two layers. Upper layer contains biodiesel dissolved in hexane; whereas, excess alcohol, glycerol and other impurities gets separated with water at bottom layer. Repeated water wash is given to biodiesel till its pH becomes neutral to remove catalyst molecules from the biodiesel (Mathimani et al. 2015, El-Shimi et al. 2013). The addition of hexane along with the reaction mixture significantly increases the yield of biodiesel as post transesterification the biodiesel synthesised gets dissolved in hexane and facilitates the recovery of biodiesel (Sánchez et al. 2012; Dianursanti et al. 2015).

Transesterification of triglycerides in the presence of methanol and catalyst results in the production of biodiesel and glycerol as the byproduct. Glycerol forms the major byproduct of biodiesel industries which remains in its crude form. Pure glycerol has intensive applications in food, pharma, cosmetic and polymer industries but industrial crude glycerol contains many contaminants and requires multiple purification steps to make it suitable to be used in product based industries. Bioconversion of this waste glycerol to numerous value-added products can be a possible source of additional revenue and financial viability and sustainability for biodiesel industry.

Pigments and vitamins

Microalgae are rich source of nutrition and can be considered as bio-based crop for future (Draaisma et al. 2013). Microalgae derived pigments have wide applications in various industries including pharmaceutical, cosmetic, food and nutraceutical. These photosynthetic pigments can be categorised into three major classes viz., chlorophylls, phycobilins and carotenoids (xanthophylls and carotenes). Chlorophylls and carotenoids are hydrophilic while phycobilins are hydrophobic and are fat-soluble. Various environmental factors effect production efficiencies of microalgae pigments such as light, temperature, salinity, pH, metal stress, nutrient supplement and limitation (Verma et al. 2009). Various spectral portions of light such as blue-red, red-far red, blue-green, green–red and blue red act as photo-morphogenic signals and directly effects pigment composition in microalgae (Kagawa et al. 2007). Light intensity stimulates pigment accumulation in microalgae. Cyanobacteria prefers low light intensities and hence favours the production of phycobiliproteins (Pagels et al. 2019) whereas Spirulina produces higher phycoerythrin and phycocyanin under higher light intensity (135 mmolphotons/m2/sec) (Madhyastha et al. 2007). Similarly, carotenoids such as β-carotene and astaxanthin content in Dunaliella salina and Haematococcus pluvialis respectively, is highly enhanced by increasing the light intensity (Pisal et al. 2005). This was interpreted by various authors that intense illumination results in excess photo oxidation leading to oxidative stress thereby generating oxygen radicals which in turn increase the production of pigments (Salguero et al. 2003).

Microalgae like Haematococcus pluvialis, Chlorella vulgaris, Dunaliella salina and the Spirulina platensis are being cultivated for vitamin extraction. Microalgae pigments like carotenoids, chlorophyll and phycobilliproteins can be used as precursors of vitamins (Paolicelli et al. 2011). Spirulina sp. is rich in carotenoid pigments which act as precursors for vitamin A and can be extracted with the help of organic solvents after saponification of algal biomas with ethanolic KOH (Mathimani et al. 2018). Provitamin such as alpha tocopherol, phylloquinone, gamma-tocopherol, retinol, canthaxanthin, phytofluene and lutein can be extracted from Tetradesmus obliquus by supercritical fluid extraction with the use of CO2. Edelmann et al. (2019) extracted riboflavin, niacin, folate and vitamin B12 form commercial microalgae powder. Riboflavin and niacin were extracted with acid water, whereas, folate and vitamin B12 were extracted with extraction buffer. Although algae being major reservoir of vitamins and pro-vitamins more than 90% of commercialised β-carotene is produced through chemical synthesis. Vitamins and pigments are high value products which can add surplus revenue to the biorefinery concept. Therefore, detailed evaluation of the factors, extraction procedures and reactor configuration is very much essential for commercial production of microalgae pigments and vitamins within a biorefinery approach.

Proteins

Microalgae also serve as the source of essential amino acids for human nutrition and can benefit in fighting malnutrition and other health issues (Edelmann et al. 2019; Raja et al. 2007). Proteins from microalgae are extracted through enzymatic hydrolysis and chemical extractions. Some new techniques assisted by microwave and ultrasound pulsed electric fields are also applied for extraction of proteins (Christaki et al. 2011). The algal protein extracted chemically with acid or alkali treatment is precipitated by centrifugation or by three phase partitioning (TPP). Few process utilised a combination of two–three methods such as acid–base treatment followed by ultrasound. (Kadam et al. 2017). Ultrasound mediated protein extraction generates cavitation at liquid solid interface which exerts pressure on the microalgae cells and force them to break out. The extraction with deionized water allow cell lysis by osmotic shock and eases the protein extraction from the algal cell, whereas, the enzymatic extraction uses polysaccharidase to extract the proteins from algal cells. The protein extraction from algal species is greatly affected by pH of extraction medium. The isoelectric point of proteins (> 6) enhances the protein solubility and stability subsequently enhancing crude protein yield from microalgae (Soto-sierra et al. 2018). The low cost feasible technique for efficient protein extraction can be mediated by simple stirring or ultrasonication followed by three phase partitioning (Chia et al. 2019). The protein extraction from microalgal cells is also affected by the pretreatment method applied for rupturing of cells via autoclave, sonication and high pressure homogenization (Parimi et al. 2015).

Other products

Microalgae biomass has also been explored extensively for production of various other biobased products that can add value to the algae biorefinery model. Microalgae biomass are rich in various biomolecules such as proteins, vitamins, lipid, minerals and pigments which can provide essential nutritional value to animal or aqua feed. It therefore acts as a potential alternative which has the ability to replace fish oil or feed thus driving towards sustainable aquaculture. Apart from providing nutrition, microalgae biomass also acts as immunostimulant thereby improvising immunity of aquatic animals (Shah et al. 2018; Charoonnart et al. 2018). Several authors have studied the application of various microalgae strains in aquaculture such as Chlorella vulgaris, Arthrospira platensis, Ascochloris spp., Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Pakravan et al. 2017; Sharma et al. 2019; Sorensen et al. 2016).

Microalgae based biofertilizer is another product that could be channelized in the microalgae biorefinery approach to validate zero waste circular bioeconomy concept. Apart from the key bioactive compounds microalgae biomass contains high NPK content making it suitable as organic manure or biofertilizer with a potential to replace the current chemical fertilizers. Recently, Khan and co-authors have studied biofertilizer potential of Chlorella minutissima and concluded to contain 1.15% P, 5.87% N and 0.28% K which is better than available organic fertilizers (Khan et al. 2018). Moreover, application of algal biomass as manure to soils would not result in volatilization of nitrogen as ammonium or loss due to leaching, as only 5% of algal nitrogen is available as mineral N (Khan et al. 2018). Other key products that has been explored by various authors are bioethanol, biohydrogen, DHA which has been detailed in Table 3.

Products from delipidified microalgae residue

Lipid extraction from microalgae biomass is an intensive process which generates surplus amounts of residual biomass which is termed as delipidified microalgal residue (DMR). Although lipid is completely extracted from these residues but it still acts as a rich source of carbohydrates, proteins, minerals and other essential elements that could be precisely utilised for development of sustainable algal bio refinery. High market price of biodiesel could be counterpoised by adding revenue from other co-products produced from by-products of the process such as DMR. Effective use of DMR for energy recovery and other value added compounds would justify the sustainability of microalgal biorefinery approach. DMR has been reported to be an excellent feedstock for production of biofuels such as biohydrogen, biomethane and bioethanol. It is also a promising raw material for biopolymer production. In this section, we have reviewed the potential of DMR to energetic and other value added compounds considering their potential to improve the economics of the microalgal biorefinery from wastewater.

Biohydrogen

After lipid recovery, DMR is still a rich source of carbohydrates and proteins which acts as organic substrate for various hydrogen producing microbes. DMRs undergo harsh oil extraction process and hence are expected to be directly converted to hydrogen or other fuels. But recent studies have showed that DMRs require pretreatment to make the cellular carbon accessible to microbial flora for production of H2 or methane. Studies also proved that pretreatment procedures like chemical, mechanical and thermochemical are beneficial for improved H2 production from DMRs. Yang et al. (2011a, b) investigated various pretreatment methods on DMR of Scenedesmus and concluded that thermo-alkaline pretreatment at 100 °C and 8 g/L NaOH resulted in a threefold increase in the yield of H2 to 45.54 mL/g-volatile solid (VS). Pretreatment resulted in improved solubilisation of carbohydrates and proteins ranging from 38 to 49% and 28 to 58% respectively. Subhash and Mohan (2014) have reported biohydrogen production from DMB of mixed microalgae using acidogenic consortia of bacteria. They have utilised untreated and acid treated (extract, slurry and solid) DMR to achieve specific hydrogen yields of 4.9, 3.3, 3.0 and 2.4 mol/kg COD of DMR extract, slurry, solid and untreated DMB, respectively. Maurya et al. (2016) have reviewed the entire process and reported various strategies to valorize de-oiled algal biomass in order to shape a sustainable algal biorefinery.

Biomethane

Biomethane is a major component of biogas which is produced by anaerobic digestion of organic wastes. The efficiency of biogas production from organic waste depends on the C/N ratio of the feedstock. DMR has high C/N ratio which makes it suitable for growth of methanogenic microbes for production of high methane content biogas. Numerous studies have been reported on biomethane production from microalgal biomass including deoiled biomass (Bohutskyi et al. 2015; Cheng et al. 2016a, b; Quinn et al. 2014; Kinnunen et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2014). These authors have optimised various process parameters for methane production from deoiled biomass of different algal strains such as Nannochloropsis salina, Auxenochlorella protothecoides, Chlorella variabilis, Chlorella sorokiniana. These studies resulted in enhanced biomethane production with a yield ranging from 140 to 380 ml CH4/g-volatile solids. Biomethane has a high calorific value and can add value to the biorefinery process. Biogas containing 70% methane could be directly used for cooking, thermal and lightning purposes. This makes it a promising value added product of microalgae biorefinery.

Bioethanol

Recently, bioethanol has gained enormous exposure due to attractive government policies demanding for blending of ethanol with gasoline ranging from 15% (E15) to 85% (E85). Although a variety of feedstocks are available but majority of current bioethanol supplies are from corn and sugarcane which are food crops and hence they are termed as first generation biofuels. Bioethanol production from food crops is not favourable since this may result in food shortages and price hikes, particularly in a developing nation like India. This has paved the way towards search for alternate sources as feedstock in order to reduce the operational cost. Reports on bioethanol production from algal biomass are available and delipdified biomass which is a byproduct of algal industries acts a potential source for bioethanol production. After lipid extraction, the left over biomass is rich in complex sugars in the form of carbohydrates which can be hydrolyzed to simple sugars by saccharification. The sugar hydrolyzates are fermented with the most commonly used yeast strain Saccharomyces cerevisiae to produce ethanol (Alam et al. 2019; Kim et al. 2020a, b). Enzymatic hydrolysis of raw or pretreated DMR has resulted in sugar yields ranging from 37 to 43% (w/w) (Pancha et al. 2016). Bioethanol yield from DMR after saccharification and fermentation has been reported by various researchers which range from 0.14 to 0.26 g/g DMR (Cheng et al. 2016a, b; Mirsiaghi et al. 2015; Goo et al. 2013; Lam et al. 2014).

Biopolymer

Delipidified biomass acts as an excellent source for biopolymers such as polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB), polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) which has attracted a great deal of attention due to their biodegradability, chemical-diversity, biocompatibility and their production from renewable carbon resources. Kumar et al. (2020) reported production of 0.43 g PHB/g dry cell weight. The current methods for commercial production of PHA/PHB utilise pure strains, defined medium under aseptic conditions which adds to the overall cost of the process thereby increasing the market price. The production cost can be reduced by utilising feedstock which are cheaper and renewable. DMR contains surplus amounts of complex polysaccharides like cellulose, starch and other nutrients. Studies are reported on application of pretreatment methods (physical, chemical, thermal and enzymatic) that breaks the complex molecules into simple easy to hydrolyze sugars. These simple molecules can be utilised by pure or mixed microbial cultures for production of biopolymers. Pure cultures belonging to species Pseudomonas, Acaligenes, Azotobacter, Bacillus and Cupriavidus necator has the ability to convert organic sugars to PHA/PHB and accumulate intracellularly. Mixed cultures obtained from activated sludge, wastewater streams, household garbage, municipal solid waste etc. acts as a good source of inoculum and substrate for accumulation of intracellular biopolymers (Salehizadeh et al. 2004). Various reports have been reported for production of biopolymers (PHA/PHB) by using DMR derived sugars (Kumar et al. 2018a, b; Chandra et al. 2019). Apart from bacterial species, few microalgae and cyanobacteria species also have the ability to accumulate PHA/PHBs intracellularly such as Chlorella fritschii, Scenedesmus almeriensis Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Neochloris oleobundans and Calothrix scytonemicola. Another approach of bioplastic production is by blending raw or deoiled microalgae biomass with other bio or petroleum based polymers or additives (Cinar 2020).

Other products

Delipidified algae biomass are the left over residue generated after extensive solvent treatment of raw algae biomass to extract lipid. The utilisation of deoiled biomass is essential in order to successfully implement the zero waste biorefinery approach. After the lipid is extracted algae biomass still contains some amount of polysaccharides, proteins and other essential elements which defines its potential to be used in aqua and animal feed. Reports suggest that deoiled biomass of Haematococcus pluvialis when fed to shrimps showed high growth rate and low feed conversion ratio as compared to the control (Ju et al. 2012). In another study, Patterson and et al. replaced 10% of fish meal with defatted algae biomass based on Navicula sp. and Nannochloropsis salina and observed no significant reduction in growth rate of Red drum fish as compared to control diet (Patterson et al. 2013, Shah et al. 2018). Another possible utilisation of defatted algae biomass is its application as biofertilizer. It has been used as a replacement of chemical fertilizer for the growth of Zea mays L and also reported to improve the organic carbon of barren soil (Maurya et al. 2016). Apart from this, delipidified biomass can be converted to syngas, bio-oil and bio-char through thermochemical conversion process such as gasification and pyrolysis (Bui et al. 2016).

Challenges and recent developments