Abstract

A 65-year-old man with remitted chest pain and no tachypnea was taken urgently to catheterization because of diffuse lung ultrasound B-lines on bedside examination. He was found to have severe left-main disease. This case emphasizes the value of ultrasound to recognize acute cardiogenic interstitial pulmonary edema despite minimal symptoms. (Level of Difficulty: Advanced.)

Key Words: acute coronary syndrome, coronary artery disease, point-of-care ultrasound, pulmonary edema, risk stratification

Abbreviations and Acronyms: CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; LV, left ventricle; POCUS, point of care ultrasound

Graphical abstract

A 65-year-old man with remitted chest pain and no tachypnea was taken urgently to catheterization because of diffuse lung ultrasound B-lines…

A 65-year-old man reported substernal chest pressure while carrying boxes at work. Although he had been told in the past that this discomfort was gastroesophageal reflux, he called 911 because of its persistence for 45 min. Paramedics upon arrival suspected ST-segment changes and administered sublingual nitroglycerin. The discomfort completely resolved.

Learning Objectives

-

•

B-lines can be detected by a brief POCUS lung examination, are a finding of interstitial pulmonary edema, and have been associated with a worse prognosis in acute coronary syndromes.

-

•

Detectable by POCUS, “flash” interstitial pulmonary edema can be an early presentation of life-threatening global LV ischemia and occur with minimal or no symptoms.

Physical Examination

Upon arrival to the emergency department, his blood pressure was 117/84 mm Hg, heart rate was 80 beats/min, respiratory rate was 16/min, and oxygen saturation was 97% on 2 l via nasal cannula. The patient denied chest discomfort or dyspnea, was in no distress, and was lying flat for examination. Neither the ED physician nor cardiologist reported jugular venous distension, murmurs, gallops, or rales.

Past Medical History

The patient reported gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia. He was taking esomeprazole, ranitidine, metoprolol, metformin, and simvastatin. He had never smoked.

Differential Diagnosis

Besides transient cardiac ischemia, the differential diagnosis included esophageal disease, musculoskeletal discomfort, and—unlikely—aortic dissection, pericarditis, or pulmonary embolism.

Investigations

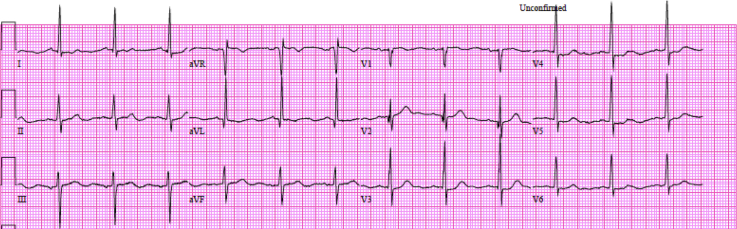

Initial troponin I level was normal, the electrocardiogram (ECG) showed no significant ST-segment changes (Figure 1), and portable chest radiograph (Figure 2) was without infiltrates or effusions.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram

Normal sinus rhythm, left ventricular hypertrophy with septal q waves, but no significant ST-T wave changes.

Figure 2.

Radiographic Findings

(A) Portable chest radiograph has no evidence of infiltrates or interstitial lung disease. (B) Chest computed tomography image shows coronary calcification but no edema or effusions.

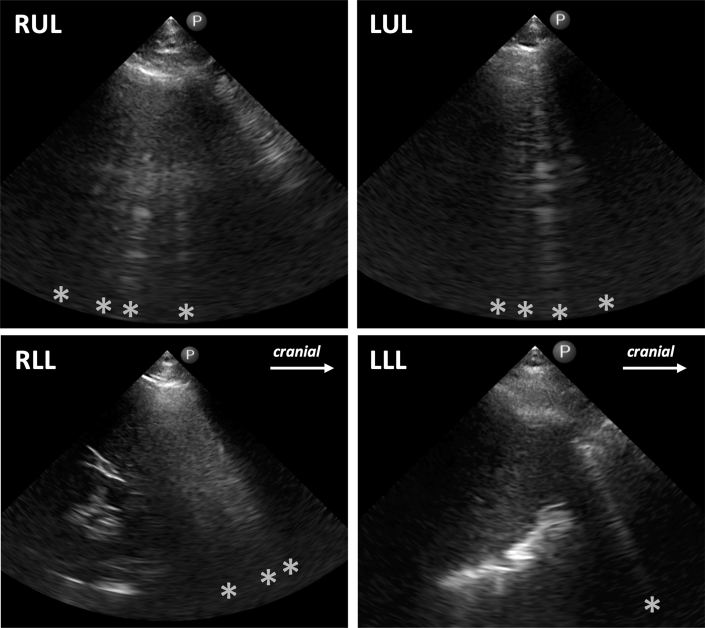

Using a cardiac ultrasound transducer (Lumify, S4-1 MHz, Philips Healthcare, Andover, Massachusetts), a 4-view point of care ultrasound (POCUS) lung examination (1) demonstrated multiple B-lines in all zones (Figure 3). An evidence-based POCUS cardiac examination (2) showed preserved left-ventricular (LV) function and a small left atrium and inferior vena cava. The patient was suspected of having flash pulmonary edema, based upon the diffuse B-lines.

Figure 3.

Ultrasound

Right upper lobe (RUL) longitudinal imaging in the third intercostal space, midclavicular line, shows 4 B-lines (∗) consistent with edema; left upper lobe (LUL) similarly shows 4 B-lines (∗); right lower lobe (RLL), coronal plane, posterior axillary line shows 3 fused B-lines (∗) partly obscuring the liver and no pleural effusion; left lower lobe (LLL) shows a single B-line (∗) and no effusion.

Management

He was given nitrates and intravenous heparin and underwent a stat limited echo en route to urgent coronary angiography. Echo data demonstrated LV ejection fraction of 55%, mild anteroseptal and inferolateral wall motion abnormalities, no significant valve disease, and normal dynamics of the right heart and inferior vena cava. Coronary angiography demonstrated critical left main coronary stenosis, occluded proximal circumflex and mid-left anterior descending arteries, a 90% posterior descending artery stenosis, and collateralization from the right coronary artery (Figure 4). Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure measured 25 mm Hg. The patient received an intra-aortic balloon pump and surgical consultation. Preoperative computed tomography (CT) scanning showed no underlying pulmonary interstitial disease or ground-glass infiltrates. He underwent successful 3-vessel bypass surgery.

Figure 4.

Coronary Angiography

(A) Left coronary artery shows severe left main lesion, occluded circumflex, and mid-left anterior descending arteries, (B) Right coronary artery shows 90% stenosis in the posterior descending artery and right-to-left collaterals.

Discussion

Acute pulmonary edema is a medical emergency in which immediate recognition can be life saving (3). Global LV ischemia can result in the rapid accumulation of fluid within the pulmonary interstitium and alveoli in so-called flash pulmonary edema. Alveolar flooding typically results in severe hypoxemia, dyspnea, cardiac crackles, and wheezing, with chest radiography noting central “batwing” infiltrates and CT demonstrating ground-glass infiltrates. Lung ultrasound has shown increased sensitivity for edema (4). With the cardiac transducer placed in the intercostal spaces in a patient with lung edema or fibrosis, abnormal vertical lines, so-called B-lines, can be seen originating from the bright horizontal pleural line in the near field and extending to the bottom of the screen. B-lines, formerly referred to as “comets” or “comet-tail artifacts,” represent a ring-down artifact caused by reverberation of the ultrasound beam within water-filled or fibrotic regions near the pleural surface, have prognostic value in hospitalized patients undergoing echocardiography (1,5,6), and have been formalized in evidence-based recommendations (7). POCUS techniques for B-lines are easy to learn and have been applied using a variety of echo platforms. Although studies have related the number of B-lines with congestive heart failure decompensation (8), few have described B-lines in flash pulmonary edema with clinical symptomatology.

We report an unusual case of acute LV ischemia resulting in B-lines without dyspnea. Presenting with <1 h of chest discomfort that the patient attributed to reflux disease and no significant findings in troponin level, ST-segment, and chest radiograph, the patient demonstrated bilateral, diffuse B-lines, quickly recognized during initial examination. At the time, the patient denied dyspnea and was in no respiratory distress. Our case shows that the enhanced sensitivity of ultrasound B-lines to detect an asymptomatic stage of interstitial edema can be life saving, perhaps allowing a novel care pathway to pre-empt the development of flash alveolar edema and its dramatic, life-threatening presentation. In addition, the lung ultrasound findings helped to narrow the differential diagnosis, as B-lines would have been atypical for gastroesophageal reflux disease, musculoskeletal pain, aortic dissection, or pulmonary embolism: diagnostic considerations that would have been erroneous and would have resulted in delays.

Association with current guidelines, position papers, and current practice

Adding to previous studies that have consistently shown the prognostic value of B-line detection in clinical presentations of dyspnea, chest pain, congestive heart failure, or acute coronary syndromes during inpatient echocardiography (1,5,6), the case presented uniquely demonstrates a “working method” of using a pocket-sized device to detect evanescent B-lines during initial physical examination. Furthermore, the ultrasound findings illustrate the physiological possibility that an early phase of pulmonary edema can exist involving primarily the interstitium that perhaps occurs before alveolar edema and pleural effusions and without severe LV systolic dysfunction or elevation of central venous pressures. The case demonstrates that a patient with a benign clinical assessment at the point of initial contact can have a malignant sign of interstitial pulmonary edema demonstrated by ultrasound.

Pocket-sized devices promote convenient ultrasound application as ultrasound stethoscopes, leveraging short boot-up times and maneuverability in the limited time and space of a patient’s bedside evaluation. Despite the undisputed value of traditional cardiopulmonary physical examination, learning to detect the simple, more accurate POCUS equivalents of those signs (9) has had only lukewarm adoption by practicing cardiologists, despite diagnostic value in acute cardiac presentations (5, 6, 7,10).

Follow-up

In postoperative office follow-up, the patient had recovered uneventfully and demonstrated a normal lung ultrasound examination, with resolution of his B-lines.

Conclusions

When applied even in the absence of symptoms, a simple 4-view lung ultrasound examination may have had life-saving implications in risk stratification of acute ischemia. Emergency department physicians, cardiologists, and hospitalists should be aware of ultrasound lung B-lines in the commonplace evaluation of apparently stable patients with transient chest pain.

Footnotes

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Case Reportsauthor instructions page.

References

- 1.Garibyan V.N., Amundson S.A., Shaw D.J. Lung ultrasound findings detected during inpatient echocardiography are common and associated with short- and long-term mortality. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37:1641–1648. doi: 10.1002/jum.14511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimura B.J., Shaw D.J., Amundson S.A., Phan J.N., Blanchard D.G., DeMaria A.N. Cardiac limited ultrasound exam techniques to augment the bedside cardiac physical. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:1683–1690. doi: 10.7863/ultra.15.14.09002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ware L.B., Matthay M.D. Acute pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2788–2796. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp052699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Picano E., Scali M.C., Ciampi Q., Lichtenstein D.A. Lung ultrasound for the cardiologist. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2018;11:1692–1705. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frassi F., Gargani L., Tesorio P. Prognostic value of extravascular lung water assessed with ultrasound lung comets by chest sonography with dyspnea and/or chest pain. J Cardiac Fail. 2007;13:830–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedetti G., Gargani L., Sicari R. Comparison of prognostic value of echographic (corrected) risk score with the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) and Global Registry in Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) risk scores in acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1709–1716. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volpicelli G., Elbarbary M., Blaivas M. International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:577–591. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Picano E., Frassi F., Agricola E. Ultrasound lung comets: a clinically useful sign of extravascular lung water. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura B.J. Point-of-care cardiac ultrasound techniques in the physical examination: better at the bedside. Heart. 2017;103:987–994. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al Deeb M., Barbic S., Featherstone R. Point-of-care ultrasonography for the diagnosis of acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema in patients presenting with acute dyspnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:843–852. doi: 10.1111/acem.12435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]