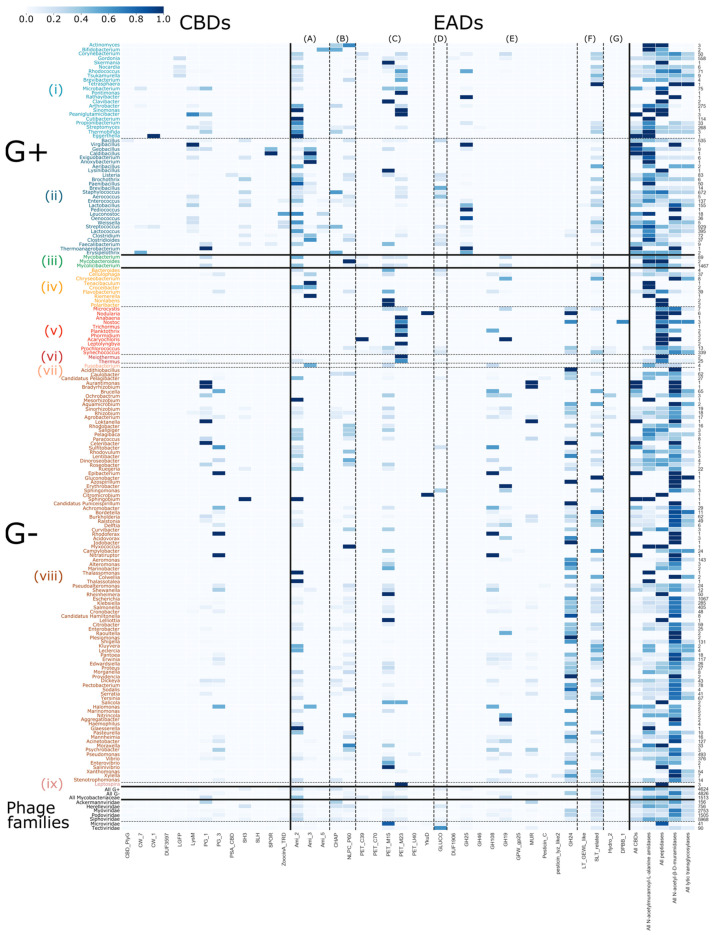

Figure 4.

Distribution of EADs and CBDs across bacterial genera. The color bar on the right denotes the probability that a domain occurs in a phage lytic protein, given its bacterial host (dark blue = 1; white = 0). The examined host phyla from top to bottom, separated by dashed and full lines, are: (i) Actinobacteria without Mycobacteriaceae (family), (ii) Firmicutes, (iii) Mycobacteriaceae (family), (iv) Bacteroidetes, (v) Cyanobacteria, (vi) Deinococcus-Thermus, (vii) Fusobacteria, (viii) Proteobacteria and (ix) Spirochaetes. The enzymatic domains from left to right, separated by dashed lines, are: (A) N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidases, (B) domains with mixed N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidases and peptidase activity, (C) peptidase domains, (D) N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase domains, (E) N-acetyl-β-D-muramidase domains, (F) domains with N-acetyl-β-D-muramidase and lytic transglycosylase activity and (G) lytic transglycosylase domains. On the bottom, probabilities are grouped given the host Gram-types as well as the phage families and on the right, the overall probability of domains of a given activity are set out for each bacterial host. The column of the right shows the number of proteins in PhaLP that target each host genus. Due to the sparsity in occurrence of the miscellaneous domains, only CBDs and EADs were examined in this figure. Figures S2–S4 illustrate the inverse relation, and the distributions including miscellaneous domains, respectively. Due to their size, these figures are best viewed digitally.