Abstract

Alcohol use disorders (AUD) increase susceptibility to respiratory infections by 2- to 4-fold in part because of impaired alveolar macrophage (AM) immune function. Alcohol causes AM oxidative stress, diminishing AM phagocytic capacity and clearance of microbes from the alveolar space. Alcohol increases AM NADPH oxidases (Noxes), primary sources of AM oxidative stress, and reduces peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ (PPARγ) expression, a critical regulator of AM immune function. To investigate the underlying mechanisms of these alcohol-induced AM derangements, we hypothesized that alcohol stimulates CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ) to suppress Nox-related microRNAs (miRs), thereby enhancing AM Nox expression, oxidative stress, and phagocytic dysfunction. Furthermore, we postulated that pharmacologic PPARγ activation with pioglitazone would inhibit C/EBPβ and attenuate alcohol-induced AM dysfunction. AM isolated from human AUD subjects or otherwise healthy control subjects were examined. Compared with control AM, alcohol activated AM C/EBPβ, decreased Nox1-related miR-1264 and Nox2-related miR-107, and increased Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 expression and activity. These alcohol-induced AM derangements were abrogated by inhibition of C/EBPβ, overexpression of miR-1264 or miR-107, or pioglitazone treatment. These findings define novel molecular mechanisms of alcohol-induced AM dysfunction mediated by C/EBPβ and Nox-related miRs that are amenable to therapeutic targeting with PPARγ ligands. These results demonstrate that PPARγ ligands provide a novel and rapidly translatable strategy to mitigate susceptibility to respiratory infections and related morbidity in individuals with AUD.

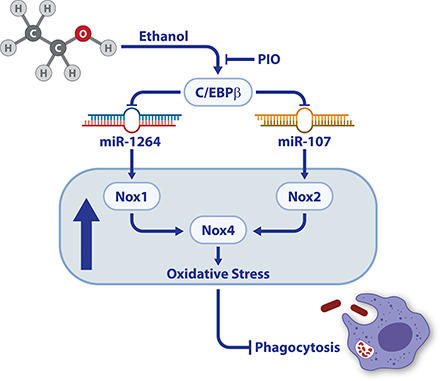

Visual Abstract

Key Points

EtOH activates AM C/EBPβ to suppress miR-1264 and miR-107.

Suppression of miR-1264 and miR-107 increases AM Noxes and oxidative stress.

PIO reverses EtOH-induced AM oxidative stress and phagocytic dysfunction.

Introduction

In 2016, approximately 100.4 million people worldwide had been diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder (AUD) (1). For more than a century, physicians have recognized that alcohol use is associated with lung infections (2). Patients with AUD have higher rates of hospitalizations and longer hospital stays (3, 4) because of increased risk of major complications, such as pneumonia (5), compared with non-AUD patients. Current evidence indicates that AUD increases susceptibility to respiratory infections through suppression of the innate immune system (6).

Excessive alcohol use impairs 1) mucociliary clearance from the upper airway by inhibiting ciliary beat function of airway epithelial cells (7), 2) barrier integrity of the alveolar epithelium by inhibiting tight junction protein expression (8), and 3) alveolar macrophage (AM) phagocytic function by inhibiting glutathione and other antioxidant pathways (9). Alcohol-induced oxidative stress contributes to lung endothelial barrier dysfunction (10) and AM phagocytic dysfunction (11, 12). Because the AM represents the first line of cellular immune defense within the alveolar space, prior studies focused on molecular mechanisms responsible for impaired AM phagocytosis and bacterial clearance and found that NADPH oxidases (Noxes) constitute primary and interrelated sources of alcohol-induced oxidative stress in the AM. Induction of either Nox1 or Nox2 led to increases in Nox4, whereas blocking either Nox1 or Nox2 partially decreased alcohol-induced levels of Nox4, and blocking both Nox1 and Nox2 exhibited a more-effective decrease in alcohol-induced Nox4 expression and activity and partially restored phagocytic function (11). The current study extends those observations by defining molecular mechanisms underlying alcohol-induced AM oxidative stress. MicroRNAs (miRs) provide a common mechanism of posttranscriptional gene regulation. MiRs bind and destabilize the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of their target mRNAs to reduce target protein levels. In the current study, TargetScan and in silico analysis were used to identify putative miRs regulating Nox1 and Nox2.

To further examine mechanisms by which alcohol modulates miR expression, we focused on putative transcription factors predicted to suppress miR promoter activity, reasoning that suppression of Nox-related miRs could account for observed alcohol-induced increases in AM Nox levels. We determined that alcohol downregulated Nox-related miRs in the AM and that these miRs were negatively regulated by the transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBPβ). Members of the CCAAT enhancer binding proteins family are basic leucine zipper transcription factors that regulate cellular differentiation and functions (13). C/EBPβ is a redox-sensitive transcription factor that is upregulated in the liver following chronic ethanol (EtOH) ingestion (14, 15).

Currently, there are no pharmacological strategies to mitigate alcohol-induced lung immune dysfunction. However, we previously demonstrated that lung barrier dysfunction in EtOH-fed mice could be attenuated with rosiglitazone, a synthetic thiazolidinedione ligand of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ (PPARγ) (10). PPARγ, a nuclear hormone receptor, regulates diverse cellular functions including AM differentiation from fetal monocytes within the lung (16). Thiazolidinedione PPARγ ligands, including rosiglitazone and pioglitazone (PIO), are currently used in clinical practice to increase insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes (17).

Chronic alcohol ingestion impairs AM phagocytic function, increasing the risk of sepsis and lung injury. The current studies demonstrate that in AM from human subjects with AUD, C/EBPβ activation reduces miR-1264 and miR-107, increases Nox1 and 2 and oxidative stress, and impairs AM phagocytosis. Furthermore, the PPARγ ligand, PIO, rapidly reverses alcohol-associated derangements in AM signaling, oxidative stress, and phagocytic function. These findings suggest that repurposing existing U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved thiazolidinedione ligands may provide a rapidly translatable and novel therapeutic approach to restoring AM function in AUD subjects. This novel intervention could potentially reduce the well-recognized morbidity and mortality associated with AUD-related lung infection and injury.

Materials and Methods

AM isolation from human subjects

All human subject protocols were reviewed and approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Health Care System Research and Development Committee. Potential subjects for study enrollment were screened using the Short Michigan Alcohol Screening Test and AUD Identification Test. Individuals with a history of AUD (n = 17) were recruited from the Substance Abuse Treatment Program at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Health Care System, and otherwise healthy control subjects (n = 17) were recruited from general Veterans Affairs medical clinics (18). Additional subject inclusion criteria included active alcohol abuse, in which the last alcoholic drink was <8 d prior to bronchoscopy. Subjects were excluded if they primarily abused substances other than alcohol, were undergoing active management of medical problems other than excessive alcohol use, were HIV positive, were >55 y old, or had abnormal chest radiographs. AUD subjects were recruited and matched with healthy controls for age, race, gender, and smoking status.

All enrolled subjects provided informed consent as previously reported (18). Following consent, fiberoptic bronchoscopy was performed in control and AUD subjects using standard clinical protocols for conscious sedation and topical anesthesia. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed in the right middle lobe where 180 ml of sterile saline was suffused in six 30-ml aliquots and withdrawn by suction. Human AMs (hAM) were isolated from the collected BAL fluid (10, 11, 18). hAM purity was determined to be ∼90% as measured by Diff-Quik (Dade Behring) staining and cell counting (19). hAM were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and cultured for 24 h prior to PIO treatment. hAM were treated with 10 μM PIO (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI) or an equivalent volume of vehicle for 24 h ex vivo. We have previously shown that ex vivo treatment with PPARγ ligands improved alcohol-mediated decreases in PPARγ expression in hAMs (20).

MH-S cells

The mouse AM cell line, MH-S (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), was used to study the effects of EtOH in vitro. MH-S cells were cultured for 24 h in RPMI 1640 media containing 10% FBS plus 1% penicillin/streptomycin, followed by treatment ± 0.08% EtOH for 3 d ± 10 μM PIO during the last 24 h of EtOH exposure (10). EtOH stimulated cells were incubated in a modular chamber (Billups-Rothenberg, Del Mar, CA) to prevent alcohol evaporation.

Transient transfections

Primary isolated hAM (1 × 106 cells) were resuspended in 100 μl of Amaxa Human Macrophage Nucleofector Kit solution (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), or MH-S cells (1 × 106 cells) were resuspended in 100 μl of Amaxa Mouse Macrophage Nucleofector Kit solution (Lonza) containing 50 nM control (scrambled oligonucleotides for miR-1264 [miR-1264-Scr] or miR-107 [miR-107-Scr]); combined miR-1264-Scr + miR-107-Scr, miRNA mimics for miR-1264 (miR-1264-M) or miR-107 (miR-107-M), or combined miR-1264-M + miR-107-M; or 20 nM C/EBPβ-Scr or siC/EBPβ, followed by nucleofection according to the manufacturer’s protocol using program Y-001. Transfected hAM were then cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and transfected MH-S cells were then cultured in RPMI 1640 media containing 10% FBS plus 1% penicillin/streptomycin for 24 h.

miR and RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

The species conserved database, TargetScan 5.1, and in silico analysis of the 3′ UTR of Nox1 and Nox2 were used to identify binding sites for miR-1264 and miR-1982 on the Nox1 3′ UTR and miR-103 and miR-107 on the Nox2 3′ UTR. mirVana miRNA isolation kits (Ambion-Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) were used to isolate miRs from hAM, MH-S cells, or mouse AM (1 × 106 cells each). miR levels were measured and quantified using methods previously described (21) and specific miR primers: miR-1264-5p (forward) 5′-AGGTCCTCAATAAGTATTTGTT-3′ and (reverse) 5′-AACAAATACTTATTGAGGACCT-3′, miR-1982-5p (forward) 5′-TTGGGAGGGTCCTGGGGAGG-3′ and (reverse) 5′-CCTCCCCAGGACCCTCCCAA-3′, miR-103-5p (forward) 5′-GGCTTCTTTACAGTGCTGCCTTG-3′ and (reverse) 5′-CAAGGCAGCACTGTAAAGAAGCC-3′, and miR-107-5p (forward) 5′-AGCTTCTTTACAGTGTTGCCTTG-3′ and (reverse) 5′-CAAGGCAACACTGTAAAGAAGCT-3′. Values for each target are expressed relative to miRNA levels of ribosomal 5U in the same sample.

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to extract total RNA from hAM (1 × 106 cells). mRNA levels of Noxes were measured and quantified using specific mRNA primers described previously (11, 22). mRNA levels of C/EBPβ were determined and quantified by quantitative RT-PCR and using specific mRNA primers: human C/EBPβ (forward) 5′-GACAAGCACAGCGACGAGTA-3′ and (reverse) 5′-AGCTGCTCCACCTTCTTCTG-3′ and mouse C/EBPβ (forward) 5′-CAAGCTGAGCGACGAGTACA-3′ and (reverse) 5′-AGCTGCTCCACCTTCTTCTG-3′. Values for each target are expressed relative to mRNA levels of 9s in the same sample.

Confocal and fluorescent immunomicroscopy

For localization of C/EBPβ, fluorescence of tetramethyl rhodamine (TRITC)–labeled C/EBPβ was confirmed with confocal microscopy at 50% of the cell depth in cells costained with the nuclear indicator DAPI (300 nM for 10 min), as previously described (9). Protein levels of Noxes were assessed by fluorescent immunomicroscopy (23), and C/EBPβ were assessed by confocal immunomicroscopy (12). Quantitating protein targets with these immunostaining methods correlated well with Western blotting of the same targets in MH-S cells, as previously reported (11). In brief, hAM cell pellets were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, cultured for 24 h, and fixed to chamber slides with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells (1.2 × 105) were then incubated with primary Abs (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for Nox1 (1:100), Nox2 (1:100), Nox4 (1:100), and C/EBPβ (1:50), followed by incubation with fluorescent TRITC-labeled secondary Abs. Confocal and fluorescent microscopy images were obtained with FluoView analysis (Olympus, Melville, NY) following staining. Fluorescence units of other TRITC-target stained cells were normalized to DAPI nuclear stain in the same cells and were expressed as fold change of mean relative fluorescent units (RFU) per cell ± SEM, relative to untreated control samples. Cell treatments did not significantly alter DAPI staining, and small within-group differences in DAPI staining were normalized as reported (20). RFU were measured in at least 10 cells per field for which there were 10 fields per experimental condition. Microscope gain and γ settings were consistent for each field and experimental condition.

Cellular reactive oxygen species production

Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production was assessed in hAM (1.2 × 105 cells) by incubating cultured cells with 5 μM 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, Invitrogen) in RPMI 1640 at 37°C for 30 min in the dark (11, 12). Fluorescence was measured using FluoView (Olympus) via quantitative digital analysis as previously reported (20). ROS production values are expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to average control values.

Amplex Red assay (Invitrogen) was used to measure hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) released into media collected from hAM (1.2 × 105 cells). Briefly, hAM cells were incubated with 500 μl of Amplex Red (20 μM) and HRP (0.1 U/ml) at 37°C for 30 min in the dark (11, 12). Fluorescence of reaction mixtures was measured in duplicate (excitation 540 nm, emission 590 nm), and H2O2 concentrations were calculated using standard curves as previously described (20). H2O2 concentrations were normalized to cellular protein concentrations (determined using bicinchoninic acid assay) and are expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to average control values.

Phagocytosis

pHrodo Staphylococcus aureus BioParticles conjugate (Invitrogen) was used to determine in vitro phagocytic capacity (19) of hAM, MH-S cells, or mouse AM (1.2 × 105 cells each). As reported (20), hAM were incubated with 1 × 106 particles of pH-sensitive pHrodo S. aureus BioParticles conjugate for 2 h, followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. Phagocytosis of bacteria was analyzed using an Olympus confocal microscope, and cells from 10 fields per experimental condition were assessed using quantitative digital fluorescence imaging software (Olympus FluoView 300, Version 4.3). To measure S. aureus internalization, argon/krypton laser confocal microscopy was performed at 50% of cell depth using identical background and gain settings. All cells with internalized bacteria were considered positive for phagocytosis. Phagocytic index (calculated as the percentage of cells positive for phagocytosis multiplied by the RFU of S. aureus per cell) was used to quantify phagocytosis and is expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to average control values.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Because all studies were conducted with more than two groups, statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests to detect differences between individual groups (GraphPad Prism version 5, San Diego, CA). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

miR mimics reverse alcohol-induced alterations in Nox expression, oxidative stress, and phagocytic dysfunction in hAM in vitro

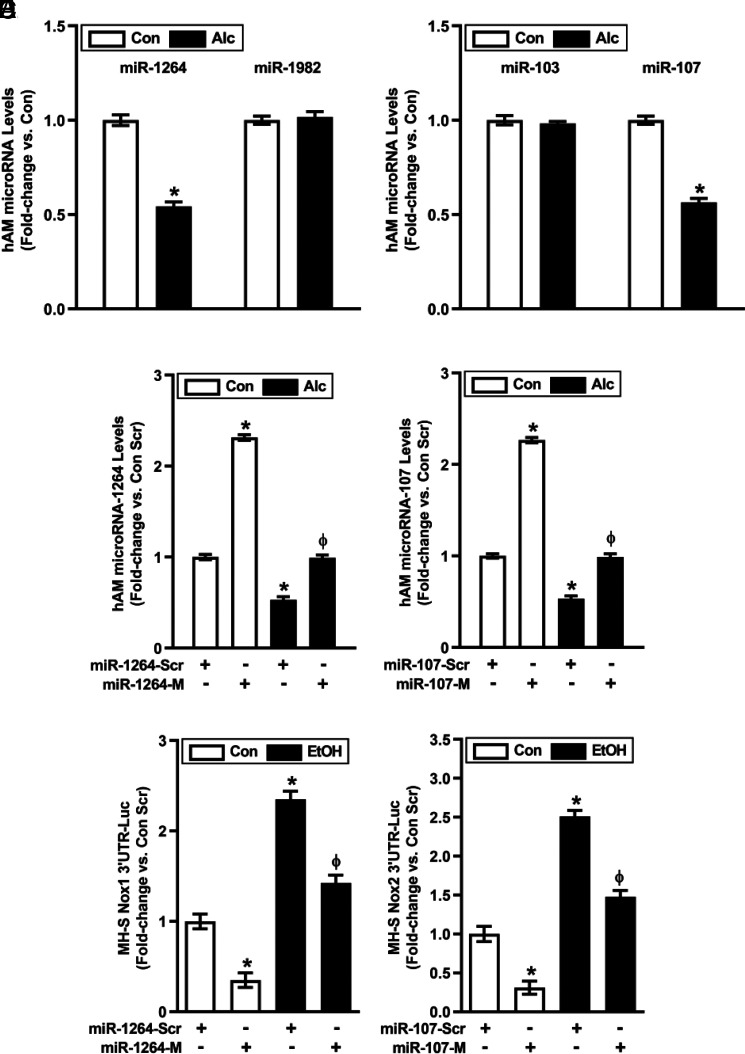

To investigate the molecular mechanisms responsible for alcohol-induced increases in AM Nox1 and Nox2 (11), we used in silico analysis to identify Nox1-related miR-1264 and miR-1982 as well as Nox2-related miR-103 and miR-107 expression for further examination. Compared with controls, levels of miR-1264 and miR-107 were decreased in hAM from AUD subjects (Fig. 1A, 1B), whereas levels of miR-1982 and miR-103 were unchanged and were therefore not examined further. Transfecting hAM with mimics of miR-1264 and/or miR-107 (Fig. 1C, 1D) restored levels of their respective miRs in hAM from AUD subjects. To confirm that these miR mimics directly regulated AM Nox1 and 2, MH-S mouse AM cells were cotransfected with Nox1 or Nox2 3′ UTR luciferase reporter constructs and miR-1264 or miR-107 mimics, respectively. As expected, alcohol reduced Nox-1 and Nox-2 MH-S 3′ UTR luciferase activity, and these reductions were reversed by treatment with mimics of miR-1264 (Fig. 1E) or miR-107 (Fig. 1F), respectively. These findings support direct regulation of Nox-1 by miR-1264 and Nox-2 by miR-107.

FIGURE 1.

Transfection with miR-1264 mimic and miR-107 mimic increases miR-1264 and miR-107 levels, respectively, in hAM. hAM were collected from control subjects (Con; n = 17) and from subjects with an AUD (Alc; n = 17). (A and B) miRNA levels of Nox1-related miR-1264 and miR-1982 (A) or Nox2-related miR-103 and miR-107 (B) were measured in hAM by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR; in duplicate), normalized to 5U ribosomal mRNA, and expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to control. (C and D) hAM were transiently transfected with 50 nM miR-1264 mimic (miR-1264-M), miR-107 mimic (miR-107-M), or scrambled miR mimics (miR-Scr) for 24 h. miR-1264 (C) or miR-107 (D) levels were measured in hAM (n = 17 per group) by qRT-PCR (in duplicate), normalized to 5U ribosomal mRNA, and expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to control. (E and F) MH-S cells were transiently cotransfected with either scrambled (Scr) or miR-1264 or miR-107 mimics along with Nox1 (E) or Nox2 (F) 3' UTR luciferase reporter constructs for 24 h. MH-S cells were then treated with either Con or EtOH (0.08%) conditions for 3 d (n = 6 per group). MH-S luciferase activity was measured in duplicate, normalized to protein concentrations, and expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to control (n = 6 per group). *p < 0.05 versus Con or Con Scr, Φp < 0.05 versus Alc Scr or EtOH Scr.

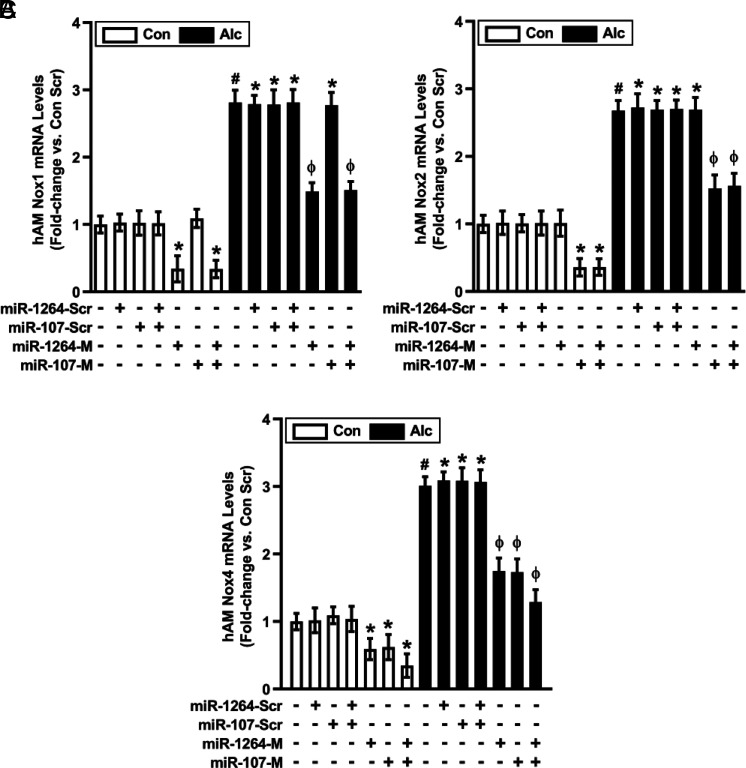

As expected, treatment with miR-1264 mimic or combined treatment with miR-1264 + miR-107 mimics downregulated basal and alcohol-induced Nox1 mRNA levels (Fig. 2A). Similarly, miR-107 mimic or combined miR-1264 + miR-107 mimics downregulated basal and alcohol-induced Nox2 mRNA levels (Fig. 2B). Consistent with previous evidence that Nox1 and Nox2 contribute to alcohol-induced increases in AM Nox4 expression (11), miR-1264 mimic, miR-107 mimic, or combined miR-1264 + miR-107 mimics downregulated basal and alcohol-induced Nox4 mRNA levels (Fig. 2C). In addition to reducing Nox1, 2, and 4 mRNA levels, miR mimics induced concomitant decreases in Nox1, 2, and 4 protein levels (Fig. 3A–C). The Nox isoform specificity of miR mimics is supported by evidence that miR-107 mimic did not alter basal or alcohol-induced Nox1 expression levels (Fig. 2A, 3A), and miR-1264 mimic did not alter basal or alcohol-induced Nox2 expression levels (Fig. 2B, 3B).

FIGURE 2.

Alcohol-induced mRNA expression of Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 in hAM are modulated by miR-1264 and miR-107. hAM were collected from control subjects (Con; n = 17) and from subjects with an AUD (Alc; n = 17). hAM were transiently transfected with 50 nM miR-1264 mimic (miR-1264-M), miR-107 mimic (miR-107-M), combined miR-1264-M + miR-107-M, or scrambled miR mimics (miR-Scr) for 24 h. mRNA levels of Nox1 (A), Nox2 (B), and Nox4 (C) were measured in hAM by quantitative RT-PCR (in duplicate), normalized to 9s mRNA, and expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to control. *p < 0.05 versus Con Scr, #p < 0.05 versus Con, Φp < 0.05 versus Alc Scr. Scr, scrambled.

FIGURE 3.

Alcohol-induced protein expression of Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 in hAM is modulated by miR-1264 and miR-107. hAM were collected from control subjects (Con; n = 17) and from subjects with an AUD (Alc; n = 17). hAM were transiently transfected with 50 nM miR-1264 mimic (miR-1264-M), miR-107 mimic (miR-107-M), combined miR-1264-M + miR-107-M, or scrambled miR mimics (miR-Scr) for 24 h. Protein expression of Nox1 (A), Nox2 (B), and Nox4 (C) was determined in hAM (10 fields per condition) using fluorescence microscopy. Fluorescence was normalized to DAPI nuclear stain and expressed as mean RFU per cell ± SEM, relative to control. *p < 0.05 versus Con Scr, #p < 0.05 versus Con, Φp < 0.05 versus Alc Scr. Scr, scrambled.

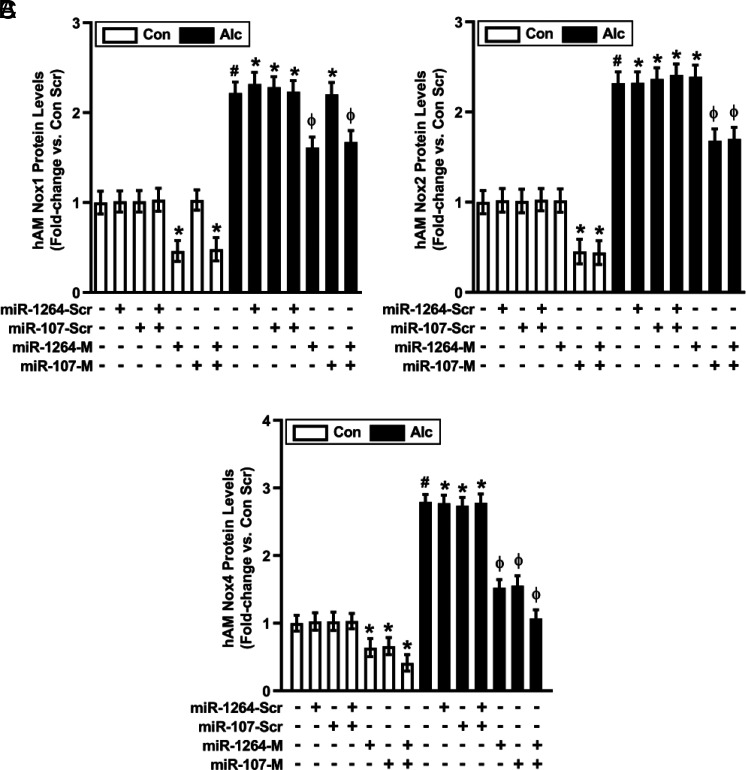

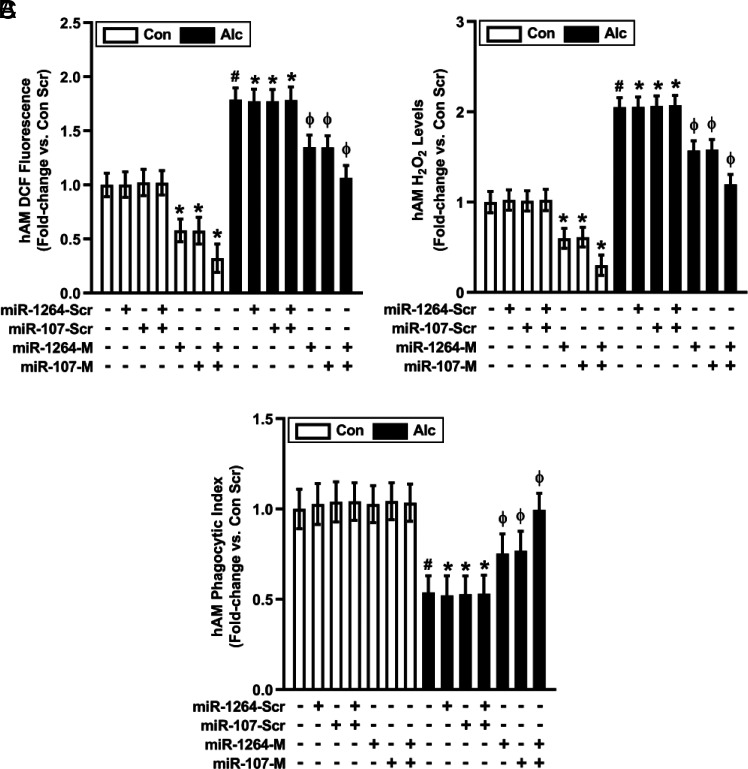

In addition to regulating Nox expression, the roles of miR-1264 and miR-107 in alcohol-induced AM oxidative stress and phagocytic dysfunction were examined. Compared with hAM transfected with scrambled mimics, miR-1264 mimic or miR-107 mimic decreased basal and partially reversed alcohol-mediated alterations in ROS production (Fig. 4A), H2O2 levels (Fig. 4B), and phagocytic index (Fig. 4C). Combined miR-1264 + miR-107 mimics additively effected these alterations in ROS production, H2O2 levels, and phagocytic index (Fig. 4A–C), consistent with contributions of multiple Nox isoforms to alcohol-induced AM oxidative stress and phagocytic dysfunction (11).

FIGURE 4.

Restoring levels of miR-1264 and miR-107 reverses alcohol-induced oxidative stress and phagocytic dysfunction in hAM. hAM collected from control subjects (Con; n = 17) and from subjects with an AUD (Alc; n = 17) were transiently transfected with 50 nM miR-1264 mimic (miR-1264-M), miR-107 mimic (miR-107-M), combined miR-1264-M + miR-107-M, or scrambled miR mimics (miR-Scr) for 24 h. ROS production was measured by DCFH-DA fluorescence assay (A), and H2O2 generation was measured by Amplex Red assay (B) in hAM (in duplicate). hAM phagocytic function was assessed by phagocytosis assay (10 fields per condition), and phagocytic index (C) was calculated from the percentage of phagocytic cells multiplied by the RFU of S. aureus per cell. All values are expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to control. *p < 0.05 versus Con Scr, #p < 0.05 versus Con, Φp < 0.05 versus Alc Scr. Scr, scrambled.

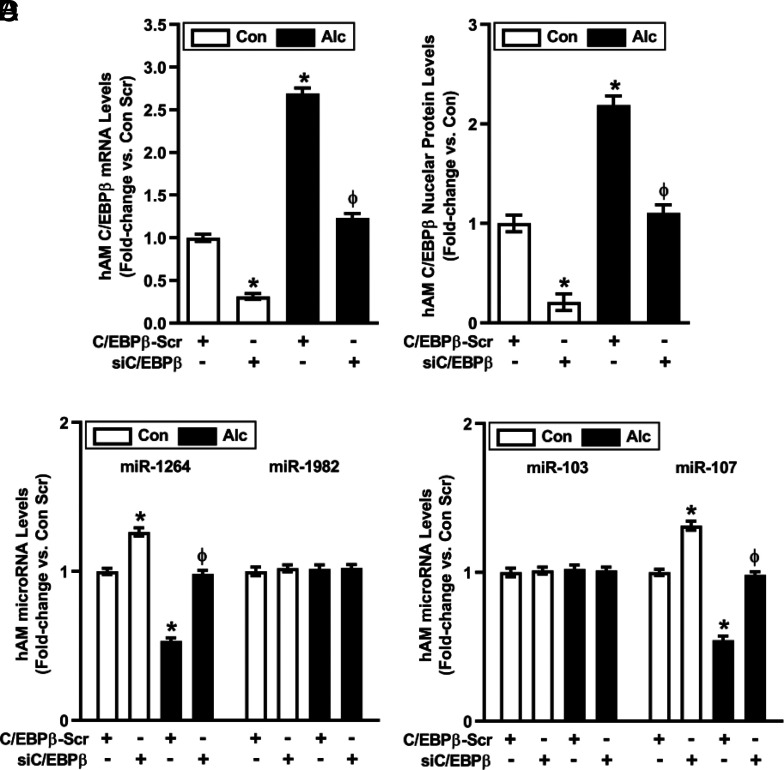

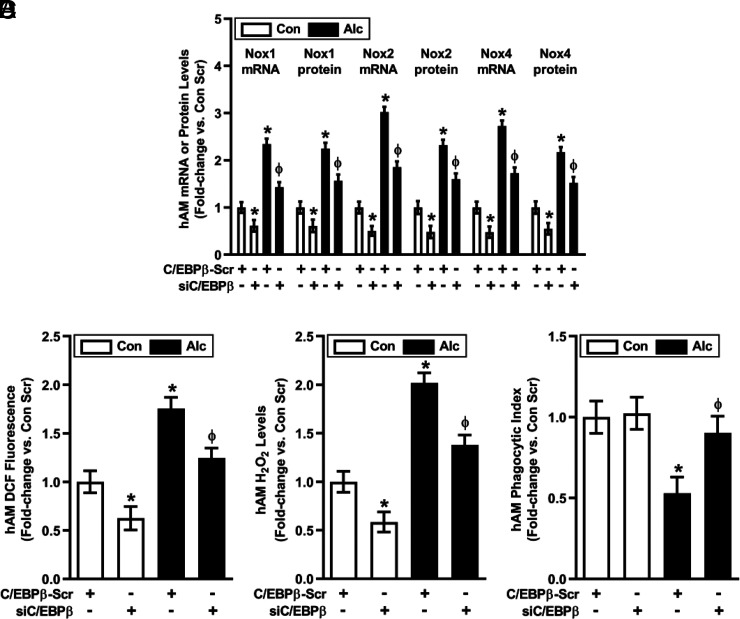

Silencing C/EBPβ reverses alcohol-induced alterations in hAM miRs, Nox expression, oxidative stress, and phagocytic function

The transcription factor, C/EBPβ, regulates miR expression and innate immune responses to microbial infections (24), and in silico promoter analysis suggested that C/EBPβ might also regulate miR-1264 and miR-107. Consistent with this postulate, alcohol increased hAM mRNA and nuclear protein levels of C/EBPβ more than 2-fold (Fig. 5), suggesting alcohol-induced transcriptional upregulation and activation of C/EBPβ. Transiently transfecting hAM with siC/EBPβ attenuated alterations in basal and alcohol-induced C/EBPβ mRNA (Fig. 5A) and cytosolic and nuclear protein (Fig. 5B) levels; Nox1-related miR-1264 levels (Fig. 5C); Nox2-related miR-107 levels (Fig. 5D); Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 6A); ROS production (Fig. 6B); H2O2 levels (Fig. 6C); and phagocytic index (Fig. 6D).

FIGURE 5.

Alcohol-induced alterations in hAM miR levels are mediated by C/EBPβ. hAM collected from control subjects (Con; n = 17) and subjects with an AUD (Alc; n = 17) were transiently transfected with 20 nM control C/EBPβ scrambled silencing RNA (siRNA) (C/EBPβ-Scr) or C/EBPβ siRNA for 24 h. (A) mRNA levels of C/EBPβ were measured in hAM by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR; in duplicate), normalized to 9s mRNA, and expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to control. (B) Nuclear protein expression of C/EBPβ was determined in hAM (10 fields per condition) using confocal fluorescence microscopy. Fluorescence was normalized to DAPI nuclear stain and expressed as mean RFU per cell ± SEM, relative to control. miR levels of Nox1-related miR-1264 (C) and Nox2-related miR-107 (D) were measured in hAM by qRT-PCR (in duplicate), normalized to 5U ribosomal mRNA. All values are expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to control. *p < 0.05 versus Con Scr, Φp < 0.05 versus Alc Scr. Scr, scrambled.

FIGURE 6.

Alcohol-induced alterations in hAM phenotype are mediated by C/EBPβ. hAM collected from control subjects (Con; n = 17) and from subjects with an AUD (Alc; n = 17) were transiently transfected with 20 nM control C/EBPβ scrambled silencing RNA (siRNA) (C/EBPβ-Scr) or C/EBPβ siRNA for 24 h. (A) mRNA levels of Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 were measured in hAM by quantitative RT-PCR (in duplicate), normalized to 9s mRNA, and expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to control. Protein expression of Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 was determined in hAM (10 fields per condition) using fluorescence microscopy. Fluorescence was normalized to DAPI nuclear stain and expressed as mean RFU per cell ± SEM, relative to control. ROS production was measured by DCFH-DA fluorescence assay (B), and H2O2 generation was measured by Amplex Red assay (C) in hAM (in duplicate). hAM phagocytic function was assessed by phagocytosis assay (10 fields per condition), and phagocytic index (D) was calculated from the percentage of phagocytic cells multiplied by the RFU of S. aureus per cell. All values are expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to control. *p < 0.05 versus Con Scr, Φp < 0.05 versus Alc Scr. Scr, scrambled.

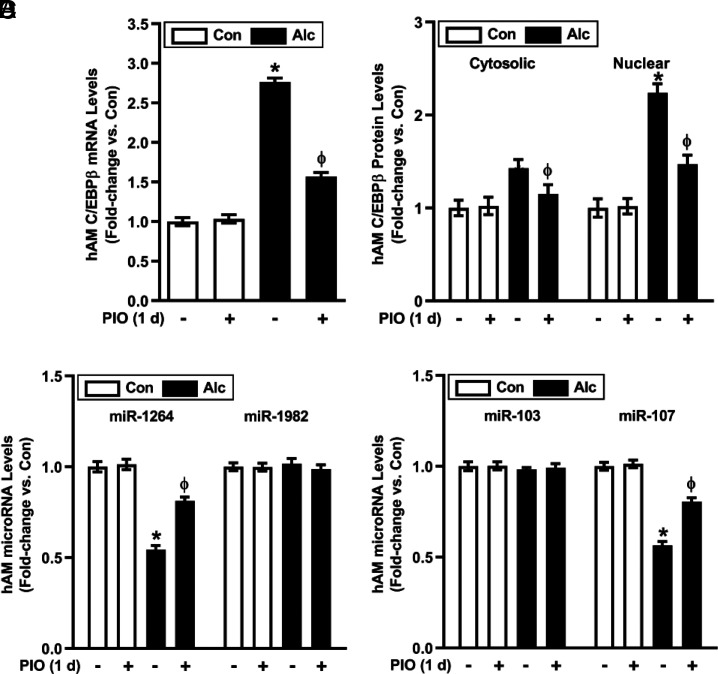

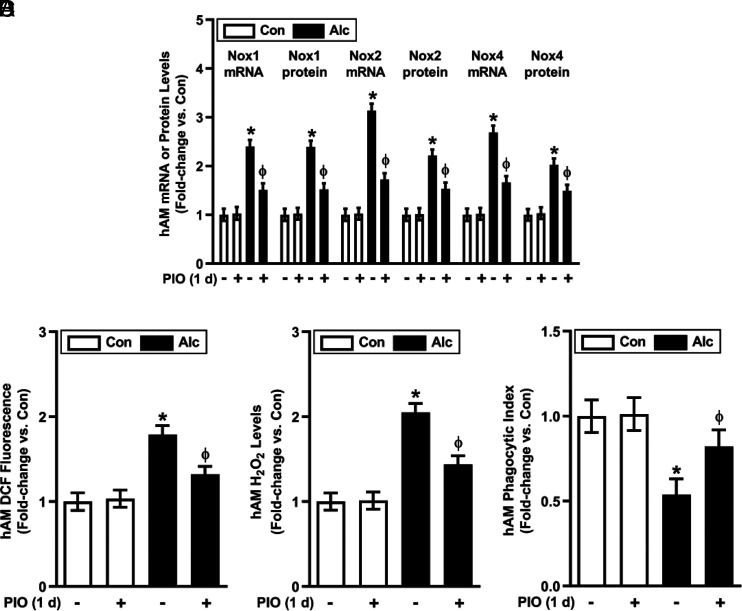

PIO reverses alcohol-mediated alterations in hAM C/EBPβ, miRNA, Nox expression, oxidative stress, and phagocytic dysfunction in AM

Because pharmacological activation of the PPARγ receptor can mitigate oxidative stress in the lung (10), we sought to determine if the PPARγ ligand, PIO, could reverse alcohol-induced derangements in hAM gene expression and function. C/EBPβ mRNA and protein (cytosolic and nuclear) were upregulated in hAM from AUD subjects (Fig. 7A, 7B). Although alcohol increased C/EBPβ in cytosolic fractions, more robust increases in nuclear C/EBPβ protein (Fig. 7B) indicate C/EBPβ transcriptional upregulation, nuclear translocation, and activation. PIO partially attenuated EtOH-induced increases in C/EBPβ and decreases in miR-1264 and miR-107 levels in hAM ex vivo (Fig. 7A–D). Similarly, treatment with PIO ex vivo for 24 h attenuated alcohol-induced derangements in Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 8A); ROS production (Fig. 8B); H2O2 levels (Fig. 8C); and phagocytic index (Fig. 8D). These results provide novel evidence that short-term treatment with PIO attenuates alcohol-induced derangements in AM gene expression, oxidative stress, and phagocytic function.

FIGURE 7.

PIO reverses alcohol-mediated pathways that upregulate Nox isoform expression in hAM. hAM were collected from control subjects (Con; n = 17) and from subjects with an AUD (Alc; n = 17). hAM were then treated ± PIO (10 μM) ex vivo for 1 d. (A) mRNA levels of C/EBPβ were measured in hAM by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR; in duplicate), normalized to 9s mRNA, and expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to control. (B) Cytosolic and nuclear protein expression of C/EBPβ was determined in hAM (10 fields per condition) using confocal fluorescence microscopy. Fluorescence was normalized to DAPI nuclear stain and expressed as mean RFU per cell ± SEM, relative to control. miR levels of Nox1-related miR-1264 and miR-1982 (C), and Nox2-related miR-103 and miR-107 (D) were measured in hAM by qRT-PCR (in duplicate), normalized to 5U ribosomal mRNA, and expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to control. *p < 0.05 versus Con, Φp < 0.05 versus Alc.

FIGURE 8.

PIO reverses alcohol-induced derangements that cause phagocytic dysfunction in hAM. hAM were collected from control subjects (Con; n = 17) and from subjects with an AUD (Alc; n = 17). hAM were then treated ± PIO (10 μM) ex vivo for 1 d. (A) mRNA levels of Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 were measured in hAM by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR; in duplicate), normalized to 9s mRNA. Protein expression of Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 were determined in hAM (10 fields per condition) using fluorescence microscopy. Fluorescence was normalized to DAPI nuclear stain and expressed as mean RFU per cell. (B) hAM ROS production was measured by DCFH-DA fluorescence assay and expressed as mean RFU per cell. (C) H2O2 generation was measured by Amplex Red assay (in duplicate) and normalized to protein concentration in the same sample. (D) hAM phagocytic ability was assessed by phagocytosis assay (10 fields per condition). Phagocytic index was calculated from the percentage of cells positive for bacterial uptake multiplied by the RFU of S. aureus per cell. All values are expressed as mean ± SEM, relative to control. *p < 0.05 versus Con, Φp < 0.05 versus Alc.

Discussion

Individuals with a history of AUD have increased susceptibility to respiratory infections because of functional immunosuppression of the AM. Our goal has been to clarify how alcohol perturbs AM function in hopes that new therapeutic targets could be identified to inform novel therapeutic strategies. Although excessive oxidative stress mediated by Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 upregulation causes alcohol-induced AM phagocytic dysfunction (11), the molecular mechanisms underlying these events remained to be defined. Our previous studies demonstrated that EtOH increases ROS and H2O2 via upregulation of Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 in AM but decreases their phagocytic function (11). Treatment with the antioxidant glutathione restored Klebsiella pneumoniae clearance in BAL fluid and AM (12). The current study focuses on C/EBPβ and Nox-related miRs as novel mechanisms of AM immune regulation. We hypothesized that alcohol-induced reductions in AM PPARγ contribute to increased C/EBPβ, leading to suppression of Nox-related miRs and Nox upregulation, oxidative stress, and AM phagocytic dysfunction. In contrast, PPARγ activation with PIO reversed these alcohol-induced AM derangements, providing, to our knowledge, the first description of a potential therapeutic intervention to reduce alcohol-associated AM dysfunction and respiratory infections.

Whereas the current studies focus on derangements in hAM isolated from AUD subjects and their modulation by ex vivo treatment with PIO, we have observed virtually identical derangements in gene expression and function in AM isolated from a mouse model of chronic alcohol ingestion (20) and in MH-S cells treated with alcohol in vitro (data not shown). Collectively, these observations provide compelling evidence that alcohol is the proximal stimulus for these alterations. The preponderance of evidence in this report indicates that C/EBPβ directly affects miR-1264 and miR-107 to regulate Nox1 and Nox2, respectively, and that PIO modulates these pathways through C/EBPβ. It is important to recognize that other reactive species or signaling molecules could also contribute to these molecular events. However, consistent alcohol-induced alterations in C/EBPβ, downstream miRs, and AM derangements along with their attenuation with PIO emphasize these molecular targets as critical for effects of alcohol on the AM. The consistency of our observations across models and species, despite variations in the duration of alcohol exposure, provides reassurance that the pathways examined are of fundamental importance in the pathobiology of alcohol-induced derangements in AM function.

We previously reported that ex vivo treatment with the PPARγ ligand, rosiglitazone, for 24 h increased hAM PPARγ levels that had been depleted by chronic alcohol consumption (20). Current evidence that PIO reversed alcohol-induced AM derangements suggests that beneficial effects of these drugs on the alcoholic AM phenotype are attributable to the thiazolidinedione class of PPARγ ligands. However, prior studies of diabetic patients treated with thiazolidinediones described increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients treated with rosiglitazone, whereas PIO reduced cardiovascular risk, suggesting that agents within this same class may nonetheless exert unique pharmacological features and effects (17). Based on concerns regarding rosiglitazone safety, the current study used PIO to demonstrate that AUD-induced AM derangements can be rapidly reversed in 24 h. These studies suggest that pharmacological ligand activation of residual PPARγ within the AM can rapidly and beneficially impact AUD hAM gene expression and function. Although thiazolidinediones also exert pleiotropic cellular effects in pulmonary and extrapulmonary compartments, reversal AUD-related derangements in hAM with PIO ex vivo suggests that systemic effects of thiazolidinediones are not required for these beneficial effects. We have observed that in vivo treatment with oral PIO also reverses this AM phenotype in a mouse chronic alcohol ingestion model (data not shown), suggesting that clinically achievable PIO concentrations in the airway are adequate for therapeutic purposes.

In summary, the current findings are the first (to our knowledge) to demonstrate the role of C/EBPβ in the regulation of miR-1264 and miR-107 in alcohol-exposed AM. Our data demonstrate that alcohol increases the levels and activation of C/EBPβ, resulting in decreases in miR-1264 and miR-107. Reductions in these miRNAs lead to increased levels and activity of Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 in alcohol-exposed AM, contributing to oxidative stress, phagocytic dysfunction, and the abnormal alcoholic AM phenotype. The importance of these novel alcohol-induced pathways is supported by evidence that PIO, an existing pharmacological tool, rapidly reverses the alcoholic AM phenotype and restores phagocytic function. These results suggest a rapidly translatable strategy to mitigate adverse pulmonary effects of AUD. These foundational studies informed an ongoing clinical trial examining the effects of short-term (14 d) oral PIO on AM function in AUD subjects (A Study of Pleiotropic Pioglitazone Effects on the Alcoholic Lung: APPEAL Study, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03060772). This trial and related studies will determine if acute pharmacological interventions that reverse alcohol-induced pathobiological signaling can benefit individuals with AUD presenting for medical care by lessening risk of infection and lung injury.

Acknowledgments

The visual abstract was created using BioRender.com.

This work was supported in part by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants K99AA021803, R00AA021803, and R01AA026086 (to S.M.Y.), R01AA012197 (to L.A.S.B.), and 2P50AA013757 (to L.A.S.B. and C.M.H.), U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (Clinical Science Research and Development) Career Development Award 1IK2CX000643 (to A.J.M.), and Veterans Affairs Basic Laboratory Research and Development Merit Review Award Program (1I01BX004263 to C.M.H.). The contents of this report do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Government.

- AM

- alveolar macrophage

- AUD

- alcohol use disorder

- BAL

- bronchoalveolar lavage

- C/EBPβ

- CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β

- DCFH-DA

- 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- EtOH

- ethanol

- hAM

- human AM

- H2O2

- hydrogen peroxide

- miR

- microRNA

- Nox

- NADPH oxidase

- PIO

- pioglitazone

- PPARγ

- peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ

- RFU

- relative fluorescent unit

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- TRITC

- tetramethyl rhodamine

- UTR

- untranslated region

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. GBD 2016 Alcohol and Drug Use Collaborators . 2018. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry 5: 987–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Osler W. 1892. The Principles and Practice of Medicine: Designed for the Use of Practitioners and Students of Medicine. D. Appleton and Company, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Wit M., Best A. M., Gennings C., Burnham E. L., Moss M.. 2007. Alcohol use disorders increase the risk for mechanical ventilation in medical patients. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 31: 1224–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smothers B. A., Yahr H. T.. 2005. Alcohol use disorder and illicit drug use in admissions to general hospitals in the United States. Am. J. Addict. 14: 256–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Spies C. D., Neuner B., Neumann T., Blum S., Müller C., Rommelspacher H., Rieger A., Sanft C., Specht M., Hannemann L., et al. 1996. Intercurrent complications in chronic alcoholic men admitted to the intensive care unit following trauma. Intensive Care Med. 22: 286–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yeligar S. M., Chen M. M., Kovacs E. J., Sisson J. H., Burnham E. L., Brown L. A.. 2016. Alcohol and lung injury and immunity. Alcohol 55: 51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Price M. E., Pavlik J. A., Sisson J. H., Wyatt T. A.. 2015. Inhibition of protein phosphatase 1 reverses alcohol-induced ciliary dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 308: L577–L585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schlingmann B., Overgaard C. E., Molina S. A., Lynn K. S., Mitchell L. A., Dorsainvil White S., Mattheyses A. L., Guidot D. M., Capaldo C. T., Koval M.. 2016. Regulation of claudin/zonula occludens-1 complexes by hetero-claudin interactions. Nat. Commun. 7: 12276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown L. A., Ping X. D., Harris F. L., Gauthier T. W.. 2007. Glutathione availability modulates alveolar macrophage function in the chronic ethanol-fed rat. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 292: L824–L832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wagner M. C., Yeligar S. M., Brown L. A., Michael Hart C.. 2012. PPARγ ligands regulate NADPH oxidase, eNOS, and barrier function in the lung following chronic alcohol ingestion. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 36: 197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yeligar S. M., Harris F. L., Hart C. M., Brown L. A.. 2012. Ethanol induces oxidative stress in alveolar macrophages via upregulation of NADPH oxidases. J. Immunol. 188: 3648–3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yeligar S. M., Harris F. L., Hart C. M., Brown L. A.. 2014. Glutathione attenuates ethanol-induced alveolar macrophage oxidative stress and dysfunction by downregulating NADPH oxidases. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 306: L429–L441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lekstrom-Himes J., Xanthopoulos K. G.. 1998. Biological role of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family of transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 28545–28548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen Y. H., Yang C. M., Chang S. P., Hu M. L.. 2009. C/EBP beta and C/EBP delta expression is elevated in the early phase of ethanol-induced hepatosteatosis in mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 30: 1138–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. He L., Ronis M. J., Badger T. M.. 2002. Ethanol induction of class I alcohol dehydrogenase expression in the rat occurs through alterations in CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins beta and gamma. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 43572–43577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schneider C., Nobs S. P., Kurrer M., Rehrauer H., Thiele C., Kopf M.. 2014. Induction of the nuclear receptor PPAR-γ by the cytokine GM-CSF is critical for the differentiation of fetal monocytes into alveolar macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 15: 1026–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soccio R. E., Chen E. R., Lazar M. A.. 2014. Thiazolidinediones and the promise of insulin sensitization in type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 20: 573–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mehta A. J., Yeligar S. M., Elon L., Brown L. A., Guidot D. M.. 2013. Alcoholism causes alveolar macrophage zinc deficiency and immune dysfunction. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 188: 716–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brown S. D., Gauthier T. W., Brown L. A.. 2009. Impaired terminal differentiation of pulmonary macrophages in a Guinea pig model of chronic ethanol ingestion. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 33: 1782–1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yeligar S. M., Mehta A. J., Harris F. L., Brown L. A., Hart C. M.. 2016. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ regulates chronic alcohol-induced alveolar macrophage dysfunction. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 55: 35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yeligar S., Tsukamoto H., Kalra V. K.. 2009. Ethanol-induced expression of ET-1 and ET-BR in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and human endothelial cells involves hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and microrNA-199. J. Immunol. 183: 5232–5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown S. D., Brown L. A. S.. 2012. Ethanol (EtOH)-induced TGF-β1 and reactive oxygen species production are necessary for EtOH-induced alveolar macrophage dysfunction and induction of alternative activation. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 36: 1952–1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liang Y., Harris F. L., Brown L. A.. 2014. Alcohol induced mitochondrial oxidative stress and alveolar macrophage dysfunction. BioMed Res. Int. 2014: 371593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O’Hara S. P., Splinter P. L., Gajdos G. B., Trussoni C. E., Fernandez-Zapico M. E., Chen X. M., LaRusso N. F.. 2010. NFkappaB p50-CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPbeta)-mediated transcriptional repression of microRNA let-7i following microbial infection. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 216–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]