Abstract

The world is presently struggling with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). A patient with COVID-19 typically presents with fever, non-productive cough, dyspnea, and myalgia. A 49-year-old female presented with complaints of subacute onset and progressive symmetrical proximal muscle weakness of both upper limbs and lower limbs with no sensory, cranial nerve deficit. She had elevated creatine phosphokinase levels of 906 U/L, an aspartate aminotransferase level of 126 IU/L, a lactate dehydrogenase level of 354 U/L, and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 68 mm/1 hr, and magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis and thigh revealed muscle edema suggestive of myositis. Her reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction result for SARS-CoV-2 was positive. Her evaluation for other causes of myositis was negative. She was managed with intravenous immunoglobulins and supportive care. She showed rapid improvement in symptoms and motor weakness. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of COVID-19 related disabling myositis in India.

Keywords: COVID-19, CPK, IVIG, Myositis, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

The world is presently struggling with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by single-stranded ribonucleic acid–enveloped severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). A patient with COVID-19 typically presents with fever, non-productive cough, dyspnea, and myalgias.1 Myositis due to viral infections is common with influenza A and B infection, Epstein–Barr virus infection, human immunodeficiency virus infection, cytomegalovirus infection, and so on.2 Patients with COVID-19 have shown the involvement of the central nervous system, peripheral nervous system, and skeletal muscles and tend to be older with fewer symptoms of fever/cough.3 There are various case reports of COVID-19 induced myositis and rhabdomyolysis; however, these are considered rare manifestations of COVID-19.2,4 We report a case of a middle-aged female who presented with COVID-19 induced myositis without any respiratory symptoms or signs.

Case report

A 49-year-old female patient with no known prior illness presented with subacute onset, gradually progressive, symmetric proximal muscle weakness of all four limbs of two-week duration. Initially, she noticed difficulty in getting up from the squatting position and picking up objects from overhead shelves. After 2–3 days, she experienced difficulty in getting up from a chair and reaching for objects. It was associated with severe myalgia involving both arms and thighs, and she was ambulant without support. There was no history of thinning of limbs, diurnal variation, difficulty in swallowing, double vision, other cranial nerve deficit, sensory loss, gait imbalance and bowel or bladder symptoms. She denied any history of fever, cough, sore throat, dyspnea, rashes, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, joint pain, and drug intake. She was a vegetarian and denied history of recent travel or contact with COVID-19 positive patients.

The initial examination revealed a temperature of 98.2 F, a pulse of 78/min (regular), a blood pressure of 140/88 mmHg, a respiratory rate of 16/min, a SPO2 of 98% in room air, and pallor. Systemic examination showed Medical Research Council scale grade 3 power at both hip flexors and extensors, grade 4 at both knee flexors and extensors with the hamstring weaker than the quadriceps, grade 3 power at both shoulder joints, and grade 4+ power at biceps and triceps. She had normal power at all other muscle groups and no muscle atrophy, with normal deep tendon reflexes and flexor plantar and sensory and cranial nerve examination. Laboratory investigations inclusive of the etiology of myopathy are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Laboratory parameters.

| Variables | Result |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 9.1 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fl) | 111.2 |

| Packed cell volume (%) | 38.6 |

| Total leukocyte count (cells/μL) | 3500 |

| Differential count (%) | |

| Neutrophils | 54 |

| Lymphocyte | 37 |

| Platelets (cells/μL) | 126000 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.43 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 137 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 3.7 |

| Adjusted calcium (mg/dl) (8.3–10.6) | 8.4 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) (5–40) | 126 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) (16–63) | 62 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) (44–147) | 108 |

| Protein (g/dl) (5.7–8.2) | 5.3 |

| Albumin (g/dl) (4.0–4.7) | 2.9 |

| Prothrombin time (control: 11.5 s) | 12.9 |

| INR | 1.01 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/1hr) | 68 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | Negative |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) (81–234) | 354 |

| Creatine phosphokinase (U/L) (26–192) | 906 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) (23–336) | 145.7 |

| D-Dimer (ng/dl) (0–200) | 200 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/ml) (0–0.5) | 0.08 |

| Serum vitamin B12 (pg/ml) (211–911) | 140 |

| Serum folic acid (ng/ml) (2.6–12.2) | 10.16 |

| Total 25-hydroxy vitamin D (ng/ml) (<10 deficient) | 9.37 |

| Parathyroid stimulating hormone | Not performed |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Negative |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) | Negative |

| Anti–hepatitis C virus | Negative |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (mcIU/ml) (0.4–4.2) | 2.69 |

| Antinuclear antibody (ANA) by immunofluorescence | Negative |

| ANA profile by immunoblot | Negative |

| Cytoplasmic antineutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA) | Negative |

| Perinuclear ANCA | Negative |

| Acetylcholine receptor–binding antibodies (nMol/L) (0–0.4) | <0.01 |

| Myositis panel | Negative |

| Borrelia burgdorferi IgM/IgG | Negative |

| Tumor markers | Negative |

| Peripheral blood smear | Hypersegmented neutrophils and macrocytic anemia |

International normalized ratio (INR).

She was managed with 2 g/kg of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) divided over 5 days and supportive care. She showed rapid improvement in symptoms within 24 h, with regaining of motor power to grade 4+ in both upper and lower limbs, with resolution of myalgias and tenderness. She could get up from the squatting position and was able to carry out daily activities. Investigations showed the following: a reduction in the creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level, 54 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level, 60 IU/L; and a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 258 U/L. Her reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) result for SARS-CoV-2 after 10 days was negative and was discharged on vitamin B12 and vitamin D3 supplements. A follow-up after 14 days of discharge revealed grade 5 power in all muscle groups, with resolution of symptoms. She has been advised to do a follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of both thighs after 3 months.

Discussion

The patient was diagnosed to have COVID-19 induced myositis after ruling out common and rare causes of myositis. The basis of diagnosis was subacute onset of symmetrical proximal muscle weakness; MRI evidence of muscle edema; elevated CPK, LDH, and AST levels; positive RT-PCR results for COVID-19; and rapid improvement with treatment. Electromyography and muscle biopsy were not performed because of active COVID-19. We considered vitamin D3 deficiency a differential diagnosis of myopathy. Myopathy associated with vitamin D3 deficiency presents with long duration of muscle aches, bony pains, malabsorption, and recovery time of weeks to months after treatment.5 Vitamin B12 deficiency was an unlikely etiology as it presents with subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord, neuropathy, dementia, or neuropsychiatric abnormalities.6 Vitamin B12 and vitamin D3 supplements were given after the resolution of symptoms and normalization of CPK levels, which negates the possibility of them as a cause.

Myalgias without any motor weakness are frequent manifestations of various viral illnesses and COVID-19.7 A study in China showed the prevalence of myalgias (14.9%) and elevated CPK levels (13.7%) in patients with COVID-19.1

In the literature search, we could find two case reports on COVID-19 induced myositis along with MRI evidence of myositis.8,9 There were few case reports on on COVID-19 related myositis with rhabdomyolysis, and these patients had elevated CPK levels but without MRI-proven myositis.2,4 A retrospective case series from China revealed various neurological manifestations (36.4%) in patients with COVID-19, with 10.7% patients showing skeletal muscle injury.3 Patients with neurological manifestations had a more severe illness and fewer symptoms of fever and cough.3

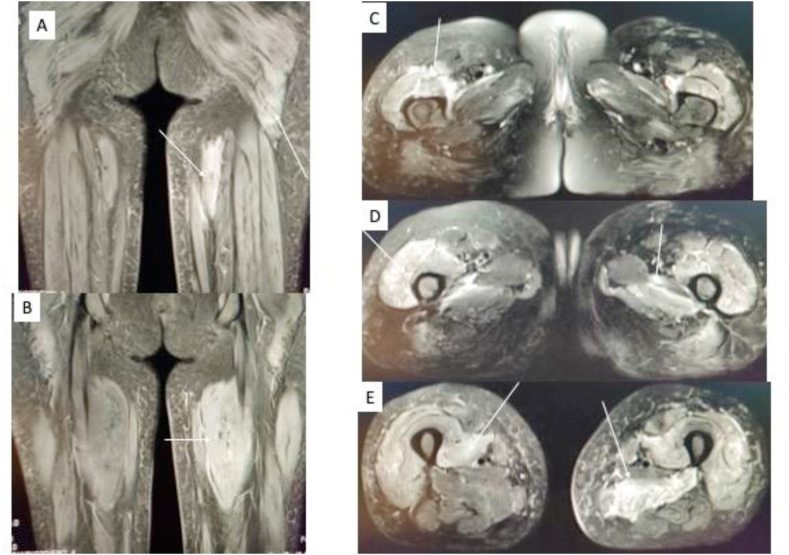

Atraumatic disorders of skeletal muscles incorporate various patterns and differential diagnosis based on MRI: pattern 1 abnormal anatomy; pattern 2 edema/inflammation; pattern 3 intramuscular mass; and pattern 4 muscle atrophy. Our patient had pattern 2 on MRI (Fig. 1), with common differentials of autoimmune, infection, drug-induced, paraneoplastic, and radiation exposure.10

Fig. 1.

MRI of the pelvis and both thighs: coronal STIR (A and B) and axial T2 FS (C, D, and E) images showing multifocal muscle edema (arrows) in the muscles of the pelvis, around the hip joint, and in multiple compartments of both thighs. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; short tau inversion recovery (STIR); stands for T2 fat suppressed (T2 FS).

As the disease is evolving, not much is known about COVID-19 induced myositis. Like any other viral myositis, it can be due to either direct viral invasion of myocytes or immunological mechanisms.11,12 Immune-mediated myositis can be due to the deposition of virus–antibody complexes on myocytes, muscle damage by circulating viral toxins, molecular mimicry between virus antigen and muscle protein, expression of muscle antigen on the cell membrane induced by the virus, and damage caused by a cytokine storm.11,12,2

In conclusion, this case highlights the importance of COVID-19 as a differential diagnosis of myositis more so when the patient presents without any respiratory symptoms or signs. The pathogenesis of myositis is likely to be immune mediated as the patient showed rapid improvement with IVIGs. Clinicians while treating COVID-19 should be aware of this complication, which is fairly simple to treat. We suggest IVIGs as a treatment option for a patient with COVID-19 who develops disabling myositis. Timely recognition and early treatment with IVIGs can prevent further complications of rhabdomyolysis.

Disclosure of competing interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gefen A.M., Palumbo N., Nathan S.K. Pediatric COVID-19-associated rhabdomyolysis: a case report. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00467-020-04617-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mao L., Jin H., Wang M. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:683–690. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Q., Shan K.S., Minalyan A., O'Sullivan C., Nace T. A rare presentation of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) induced viral myositis with subsequent rhabdomyolysis. Cureus. 2020;12 doi: 10.7759/cureus.8074. e8074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziambaras K., Dagogo-Jack S. Reversible muscle weakness in patients with vitamin D deficiency. West J Med. 1997;167:435–439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ralapanawa D.M., Jayawickreme K.P., Ekanayake E.M., Jayalath W.A. B 12 Deficiency with neurological manifestations in the absence of anaemia. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:458. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1437-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beydon M., Chevalier K., Al Tabaa O. Myositis as a manifestation of SARS-CoV-2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H., Charmchi Z., Seidman R.J., Anziska Y., Velayudhan V., Perk J. COVID-19 associated myositis with severe proximal and bulbar weakness. Muscle Nerve. 2020;6 doi: 10.1002/mus.27003. E 60-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smitaman E., Flores D.V., Mejía Gómez C., Pathria M.N. MR imaging of atraumatic muscle disorders. Radiographics. 2018;38(2):500–522. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017170112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crum-Cianflone N.F. Bacterial, fungal, parasitic, and viral myositis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:473–494. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naylor C.D., Jevnikar A.M., Witt N.J. Sporadic viral myositis in two adults. CMAJ: Can Med Assoc J. 1987;137:819. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]