Abstract

Objective

To assess the relationship between recent changes in Medicaid eligibility and preconception insurance coverage, pregnancy intention, health care use, and risk factors for poor birth outcomes among first‐time parents.

Data Source

This study used individual‐level data from the national Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (2006‐2017), which surveys individuals who recently gave birth in the United States on their experiences before, during, and after pregnancy.

Study Design

Outcomes included preconception insurance status, pregnancy intention, stress from bills, early prenatal care, and diagnoses of high blood pressure and diabetes. Outcomes were regressed on an index measuring Medicaid generosity, which captures the fraction of female‐identifying individuals who would be eligible for Medicaid based on state income eligibility thresholds, in each state and year.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

The sample included all individuals aged 20‐44 with a first live birth in 2009‐2017.

Principal Findings

Among all first‐time parents, a 10‐percentage point (ppt) increase in Medicaid generosity was associated with a 0.7 ppt increase (P = 0.017) in any insurance coverage and a 1.5 ppt increase (P < 0.001) in Medicaid coverage in the month before pregnancy. We also observed significant increases in insurance coverage and early prenatal care and declines in stress from bills and unintended pregnancies among individuals with a high‐school degree or less.

Conclusions

Increasing Medicaid generosity for childless adults has the potential to improve insurance coverage in the critical period before pregnancy and help improve maternal outcomes among first‐time parents.

Keywords: maternal and perinatal care and outcomes, Medicaid, patient protection and affordable care act, preconception care, pregnancy, unplanned, prenatal care, state health policies

What is Known on This Topic

Preconception insurance coverage is critical for increasing access to care prior to pregnancy and reducing poor maternal and infant outcomes.

Recent Medicaid expansions have been associated with increases in insurance coverage for women of reproductive age and increased access to care.

Previous research found Medicaid expansions for childless adults did not find any changes in overall preconception insurance coverage or unintended pregnancies and did not explore the impact on stress.

What this Study Adds

This is the first study to find that recent Medicaid expansions for childless adults were associated with increases in both overall insurance and Medicaid coverage in the month before pregnancy.

Medicaid expansions for childless adults were associated with declines in unintended pregnancies and stress from bills.

These findings suggest that Medicaid expansions for childless adults can reduce risk factors for poor pregnancy outcomes among nulliparous individuals.

1. INTRODUCTION

The United States continues to lag behind all other high‐income countries in rates of maternal morbidity and mortality. Rates of maternal mortality reached 17.4 deaths per 100 000 live births in 2018 and every year an additional 50 000 individuals experience a “near miss” that could have resulted in death. 1 , 2 , 3 These high rates of maternal morbidity and mortality vary greatly by state and are even more prominent among individuals of low socioeconomic status. 4 , 5 With one‐third of deaths attributable to preventable complications arising from pre‐existing, chronic conditions, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and American College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians emphasize the need to address these risk factors before pregnancy to reduce morbidity and mortality. 6 , 7

Health insurance in the preconception period has been emphasized by the CDC as critical for addressing these risk factors and poor outcomes due to its role in increasing access to preconception health care services, particularly among low‐income individuals. 8 Preconception insurance coverage has the potential to increase access to family planning and reduce unintended pregnancies, which are associated with adverse physical and mental health outcomes, including depression. 9 , 10 In addition, insurance coverage is associated with increases in preventive care, which can provide the opportunity for individuals to address modifiable risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes. 11 Identification of these risk factors before conception can improve an individual's health entering into pregnancy and reduce the risk of poor outcomes, including maternal and infant mortality. 12 , 13 , 14 Furthermore, increasing preconception coverage may reduce barriers to early prenatal care, which can lead to earlier identification and management of risk factors during pregnancy and improve outcomes. 6 , 7 , 15 Finally, increasing Medicaid generosity may reduce preconception and prenatal stress, which is associated with lower birth weights and preterm births, by reducing the potential for large medical bills. 16 , 17

Increasing insurance coverage for childless adults through state Medicaid programs may help to increase preconception insurance coverage and improve maternal outcomes. Medicaid is the payer for nearly half of all births and an important source of coverage for low‐income individuals during pregnancy; however, many childless adults enter into pregnancy without coverage or access to health care. 18 , 19 Prior to the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, only five states and the District of Columbia provided comprehensive Medicaid coverage for individuals without dependent children and, in 2009, 23% of all individuals lacked insurance in the month before conception. 18 As of February 2020, a total of 37 states have expanded Medicaid coverage under the ACA to childless adults with incomes up to 138% of the Federal Poverty Limit (FPL). 20 However, the generosity of these Medicaid programs varied significantly across states and over time both before and after the ACA due to different income thresholds and timing of program expansions. 20

Evidence suggests recent Medicaid expansions have been successful at reducing rates of uninsurance and improving access to care among reproductive‐age women. 21 , 22 , 23 Despite the importance of insurance in the critical period before pregnancy, very little is known about the impact of increasing Medicaid eligibility for childless adults on preconception insurance coverage and risk factors for poor maternal outcomes. Two recent studies did not find any changes in preconception insurance coverage and one study found no changes in pregnancy intention; however, these studies did not examine changes among childless adults who would be most impacted by the recent state Medicaid expansion and they also did not incorporate the variation in the size and timing of expansions. 24 , 25 In addition, no studies have evaluated the impact of recent Medicaid expansions on stress. This study uses national survey data to examine the association between changes in Medicaid generosity for childless adults between 2009 and 2017 and preconception insurance coverage, pregnancy intention, stress from bills, early prenatal care, and diagnoses of risk factors among first‐time parents. We hypothesized that increases in Medicaid generosity would be associated with increases in preconception insurance and reductions in risk factors for poor pregnancy outcomes.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data

The primary data source for this study was the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), the largest national survey of individuals who recently gave birth in the United States. State health departments, in collaboration with the CDC, sample individuals with a live birth from birth certificates and administer the survey by mail or telephone two to eight months after delivery. The survey includes questions regarding individual's health behaviors, attitudes, and experiences in the preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum periods. 26 The survey is updated every three to five years and this study included data from Phases 6 (2009‐2011), 7 (2012‐2015), and 8 (2016‐2017). Not all states are included in PRAMS each year, and data from states that do not meet the minimum response rate in a given year are not released by the CDC. This study included a total of 43 states that participated in PRAMS for at least one year between 2009 and 2017 (Appendix S2: Table S1).

2.2. Sample

The sample for this study included individuals aged 20‐44 who recently gave birth to their first child (“first‐time parents”), since most nulliparous individuals would only be eligible for full‐benefit Medicaid as a childless adult prior to pregnancy. Multiparous individuals were not included since prior to the ACA all states provided Medicaid coverage for parents with a median income limit of 64% of FPL so these individuals were less likely to be impacted by the recent Medicaid expansions. 27 Individuals under the age of 20 years at delivery were excluded to ensure they were not eligible for Medicaid as a child in the preconception period. Individuals without any information on age, education, race/ethnicity, number of previous births, or time since delivery were also excluded (Appendix S2: Table S2).

2.3. Medicaid generosity index

The main independent variable in this study is a “Medicaid generosity index,” which estimates the fraction of female‐identifying individuals without dependent children who would be eligible for Medicaid based on states’ eligibility rules, consistent with multiple previous studies on Medicaid expansions. 28 , 29 , 30 Although recent research on state Medicaid expansions under the ACA has often relied on difference‐in‐difference methods which simply categorize states as either expansion vs. nonexpansion, this method allows us to incorporate the variation in the extent of the expansions and the potential size of the population impacted by the change in the income limit. In addition, this method allows us to examine changes in states that increased eligibility limits multiple times during the study period. Considering the variation in Medicaid generosity both across states and over time is important since, during the study period, five states in our sample provided comprehensive coverage for childless adults before 2010 at varying income levels (Delaware, Hawaii, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont), four states expanded Medicaid between 2010 and 2014 at varying income levels (Colorado, Connecticut, Minnesota, and New Jersey), and one state (Wisconsin) increased eligibility in 2014 but only up to 100% of FPL. 20 Among the remaining states in our sample, 17 states increased eligibility from 0% to 138% of FPL between 2014 and 2016 and 16 states did not expand before 2017 (Appendix S2: Table S3). 31 For example, the index will capture the fact that New Jersey increased eligibility for childless adults from 0% to 23% of FPL in 2011 and then to 138% FPL in 2014 while Connecticut increased from 0% to 56% of FPL in 2010 and then 138% in 2014.

The Medicaid generosity index was calculated using the 2008‐2016 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) of the Current Population Survey (CPS), consistent with previous research. 28 , 29 , 30 The CPS ASEC survey includes detailed information on all individuals in a sampled household, including all sources of income in the past calendar year. Household income, household size, and income as a percent of FPL were calculated for all female‐identifying individuals aged 20‐44 years without dependent children, consistent with Medicaid eligibility rules. State Medicaid income limits were then applied to the entire sample to estimate the fraction that would be eligible for Medicaid as a childless adult in each state and year between 2008 and 2016. The index was constructed using national data pooled from all years instead of using different CPS data in each year to isolate changes in Medicaid income eligibility from changes in state social and economic characteristics. Details on the index are included in the Appendix S2.

2.4. Dependent variables

The study outcomes were selected based on two primary criteria. First, we selected preconception and pregnancy‐related outcomes that were most likely to be impacted by changes in Medicaid eligibility for childless adults. It was hypothesized that increasing Medicaid eligibility would increase preconception insurance coverage, resulting in improved access to low‐cost preconception care, including family planning and preventative services. Therefore, we expected that increases in eligibility would also be associated with declines in unintended pregnancies, earlier initiation of prenatal care, fewer diagnoses of high blood pressure and diabetes, and reductions in stress from bills. Second, we restricted our analysis to outcomes that were collected consistently by PRAMS from the survey or the birth certificate records throughout the study period (ie, all three survey phases). Some outcomes that could plausibly have been affected by preconception insurance status (eg, self‐reported diagnoses of depression and preconception health care visits) were not included because they were not collected consistently throughout the study period.

Measures of preconception insurance coverage were categorized as either Medicaid, private/other, or no insurance in the month before pregnancy and individuals could have both Medicaid and private/other insurance. The outcome capturing stress from bills was defined as any reported problems paying the rent, mortgage, or other bills in the twelve months before delivery. A pregnancy was considered unintended if the individual reported not trying to get pregnant at the time of conception.

Initiation of early prenatal care was defined in two ways. We first created a dummy variable equal to one if the first prenatal care visit was in the first trimester (12 weeks). In addition, due to the high prevalence of first‐trimester prenatal care prior to the ACA, this study analyzed the week of initiation of prenatal care among the subgroup of individuals who initiated prenatal care within the first trimester. 28 Initiation of prenatal care was based on self‐reported visits in PRAMS rather than the birth certificate variables due to changes in the prenatal care variables on the 2003 Revision of the US Standard Certificate of Live Birth, which was adopted by 20 of the 43 PRAMS states throughout the study period. 32 , 33 Diagnoses of high blood pressure and diabetes included diagnoses made both before or during pregnancy that were collected by PRAMS from birth certificates. Additional details on the outcomes are included in Appendix S2: Table S5.

2.5. Statistical analyses

To examine the relationship between changes in Medicaid generosity and outcomes among first‐time parents, outcomes of interest were regressed on the Medicaid generosity index in each state and year. All individual‐level, linear regressions included state and year fixed effects and controlled for individual characteristics, including age (categorized by PRAMS: 20‐24, 25‐29, 35‐39, and 40‐44 years), race (black, white, Asian, and other), years of education (categorized by PRAMS: 8 or less, 9‐11, 12, 13‐15, or 16 or more years), Hispanic ethnicity, marital status, month of delivery, language of survey (English or other), survey method (telephone or mail), and weeks since delivery. Regressions also included time‐varying, state‐level characteristics, including percent with college degree, median age, median household income, percent unemployed, percent white, percent black, and percent Hispanic, as well as dummy variables for whether a state had a family planning program or a contraceptive mandate in that year.

The Medicaid generosity index and state‐level characteristics were merged to the data using the year before delivery to capture the state's Medicaid generosity and socioeconomic characteristics in the preconception period. The regressions were weighted using individual‐level analysis weights provided by the CDC, which include the sampling weight and adjust for nonresponse and noncoverage. Heteroskedasticity‐robust standard errors were clustered at the state level. Results were similar using the wild cluster bootstrap‐t procedure. 34 The analyses were conducted for all first‐time parents as well as a subgroup of individuals with a high‐school degree or less (12 or fewer years of education) who were more likely to be eligible for Medicaid, consistent with prior research. 15 , 28 , 35 Although the PRAMS survey also includes questions on household size and income, these variables were not used to select individuals who would be eligible for Medicaid due to the high rate of missingness and invalid responses in those variables as well as the lack of relationship variables necessary to calculate income as a percent of FPL consistent with Medicaid eligibility rules. 36

Multiple sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of these results. First, to test whether any of the observed changes in outcomes could have been driven by changes in the overall number of births, state‐level birth rates were regressed on the generosity index in each state and year, similar to the main regression specification. Next, we tested for linear pretrends by interacting years since the start of the study period with an indicator for whether the state expanded Medicaid during the study period. In addition, a placebo test was conducted by running the regressions among individuals with a reported household income of $50 000 or higher. Although we cannot determine individual Medicaid eligibility due to the limitations of the income and dependents variables, we expect that individuals with annual incomes above $50 000 would be less likely to be impacted by Medicaid policy changes. 35 Therefore, we would not expect the generosity index to be associated with changes in the outcomes in this sample. Finally, since not all states are included in PRAMS each year, a dummy variable indicating whether a state was included in that year was regressed on the index to test whether the results were being driven by changes in the sample of states. Details of sensitivity analyses are included in the Appendix S2.

Analyses were conducted using STATA/IC 15.1. Results with P‐values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample

The study sample included a total of 112 392 first‐time parents (weighted N = 5 643 370) who gave birth in 2009‐2017 in 43 states. Details of the sample selection are included in Appendix S2: Table S2. The number of births included in each state and year is detailed in Appendix S2: Table S1.

Among all first‐time parents included in the sample, 62.7% were married, 65.4% were under the age of 30, and 72.8% had more than 12 years of education at the time of delivery (Table 1). In addition, 73.3% of individuals were white and 13.6% were Hispanic.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of first‐time parents

| All | HS or less | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 112 392 | 31 359 |

| Individual characteristics, % (SD) | ||

| Married | 62.7 (48.4) | 35.8 (47.9) |

| Age at delivery (years) | ||

| 20‐24 | 32.0 (46.6) | 59.2 (49.2) |

| 25‐29 | 33.4 (47.2) | 25.2 (43.4) |

| 30‐34 | 24.2 (42.8) | 10.5 (30.7) |

| 35‐39 | 8.6 (28.1) | 4.1 (19.9) |

| 40‐44 | 1.8 (13.4) | 0.9 (9.6) |

| Education (years) | ||

| ≤8 | 1.3 (11.5) | 4.9 (21.6) |

| 9‐11 | 4.7 (21.2) | 17.4 (37.9) |

| 12 | 21.1 (40.8) | 77.7 (41.6) |

| 13‐15 | 29.1 (45.4) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| ≥16 | 43.7 (49.6) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Race | ||

| White | 73.3 (44.3) | 66.8 (47.1) |

| Asian | 6.4 (24.5) | 4.1 (19.8) |

| Black | 12.2 (32.7) | 16.4 (37.0) |

| Other | 8.5 (27.9) | 13.1 (33.7) |

| Hispanic | 13.6 (34.3) | 25.0 (43.3) |

| Completed survey in English | 94.3 (23.1) | 85.6 (35.1) |

| Insurance coverage, % (SD) | ||

| Insurance in month before pregnancy | ||

| None | 18.5 (38.8) | 36.2 (48.1) |

| Medicaid | 9.9 (29.8) | 21.5 (41.1) |

| Private/other | 72.0 (44.9) | 43.1 (49.5) |

| Missing | 1.3 (11.2) | 2.1 (14.4) |

| Stress from bills in year before delivery, % (SD) | ||

| Experienced stress from bills | 15.2 (35.9) | 21.6 (41.1) |

| No stress from bills | 79.5 (40.3) | 72.8 (44.5) |

| Missing | 5.2 (22.2) | 5.6 (23.1) |

| Pregnancy intention, % (SD) | ||

| Unintended pregnancy | 40.0 (49.0) | 54.5 (49.8) |

| Intended pregnancy | 56.4 (49.6) | 41.7 (49.3) |

| Missing | 3.7 (18.8) | 3.8 (19.1) |

| Prenatal care | ||

| No prenatal care, % (SD) | 0.7 (8.3) | 1.2 (11.0) |

| Any prenatal care, % (SD) | 99.3 (8.4) | 98.7 (11.2) |

| Prenatal care in 1st trimester, % (SD) | 88.2 (32.3) | 78.4 (41.2) |

| Week of 1st prenatal care visit in 1st trimester, mean (SD) | 7.2 (2.3) | 7.2 (2.5) |

| Missing, % (SD) | 1.7 (13.1) | 2.7 (16.1) |

Sample restricted to first‐time parents with a live birth between 2009 and 2017. All characteristics estimated using the weights provided by the Center for Disease Control in the PRAMS data.

Abbreviations: HS, high school; SD, standard deviation.

Source: Authors’ analysis of PRAMS data pooled from Phase 6 (2009‐2011), Phase 7 (2012‐2015), and Phase 8 (2016‐2017).

A total of 31 359 (weighted N = 1 533 828) first‐time parents were included in subgroup of individuals with a high‐school degree or less. The individuals in this subgroup were less likely to be married (35.8%) and white (66.8%) and more likely to be under the age of 30 (84.4%) and Hispanic (25.0%), compared with all first‐time parents.

3.2. Regression results

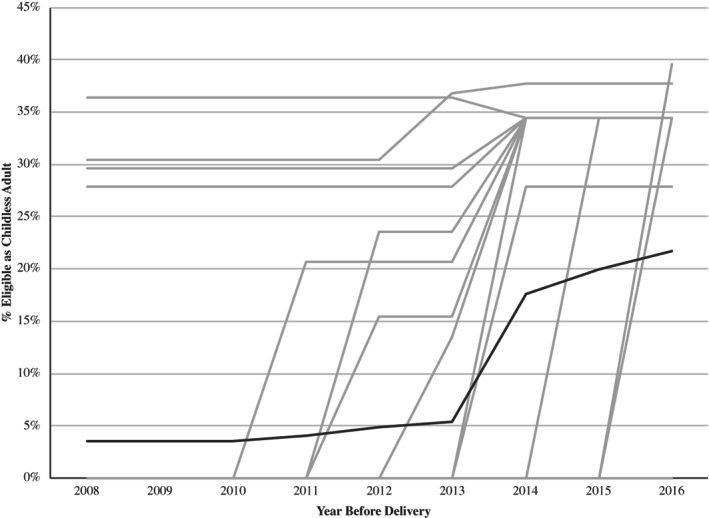

The Medicaid generosity index increased from 3.5% to 21.7% on average over the study period among all states included in PRAMS (Figure 1). However, changes in generosity varied across states; during the study period, changes in the Medicaid generosity index ranged from −1.9 to 39.6 ppts (Appendix S2: Table S4).

FIGURE 1.

Average generosity index for all states in PRAMS. Note: Figure includes the Medicaid generosity index for first‐time mothers for all 43 states included in Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring Survey (PRAMS) data at any time during the study period (2009‐2017). Individual states are shown in light gray and the average across all 43 PRAMS states is shown in dark gray

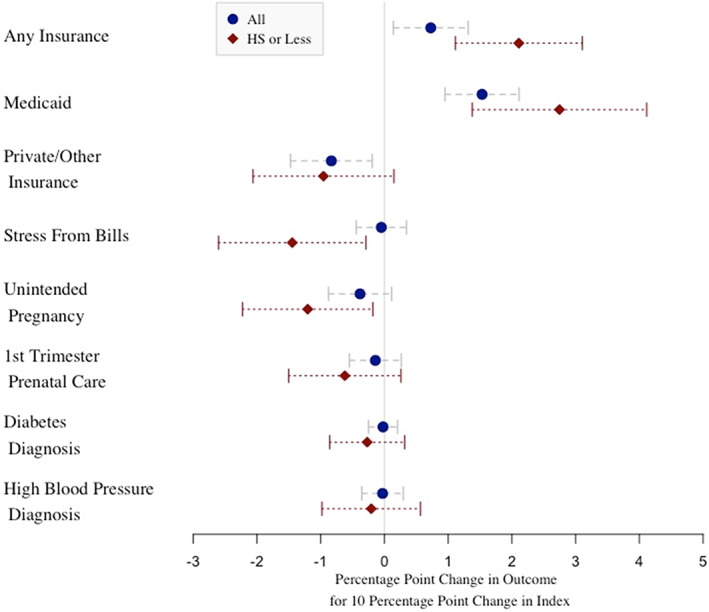

In the full sample, higher levels of Medicaid generosity were associated with higher rates of any preconception insurance, primarily due to higher rates of Medicaid coverage (Figure 2, Table 2). A 10‐ppt increase in Medicaid generosity was associated with a 0.7‐ppt (P =0.017) increase in any type of insurance, a 1.5‐ppt (P <.001) increase in Medicaid coverage, and a 0.8‐ppt decline (P =0.012) in private/other coverage. Gains in preconception insurance coverage were even greater among the subsample of individuals with a high‐school degree or less, where a 10‐ppt increase in generosity was associated with a 2.1‐ppt (P <0.001) increase in any insurance and a 2.7‐ppt (P <0.001) increase in Medicaid coverage.

FIGURE 2.

Regression results for first‐time mothers. Note: Figure includes regression coefficient and 95% confidence interval from the regressions estimated in Table 2. For results for week of initiation of prenatal care in 1st trimester, see Table 2. Regressions were estimated among all first‐time parents and first‐time parents with a high‐school degree or less

TABLE 2.

Regression results among first‐time parents

| Any insurance preconception | Medicaid preconception | Private/other insurance preconception | Stress from bills | Unintended pregnancy | Week of prenatal care in 1st trimester | First ‐trimester prenatal care | High blood pressure | Diabetes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All first‐time mothers | |||||||||

| Index 10ppt, estimate (CI) | 0.007 (0.001, 0.013)* | 0.015 (0.009, 0.021)* | −0.008 (−0.015, −0.002)* | 0.000 (−0.004, 0.003) | −0.004 (−0.009, 0.001) | −0.007 (−0.039, 0.025) | −0.001 (−0.006, 0.003) | 0.000 (−0.004, 0.003) | 0.000 (−0.003, 0.002) |

| P‐value | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.801 | 0.125 | 0.643 | 0.480 | 0.850 | 0.840 |

| Observations | 110 999 | 110 999 | 110 999 | 104 479 | 106 535 | 97 039 | 110 315 | 111 963 | 111 981 |

| Mean | 0.81 | 0.10 | 0.73 | 0.16 | 0.41 | 7.17 | 0.88 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| High school or less | |||||||||

| Index 10ppt, estimate (CI) | 0.021 (0.011, 0.031)* | 0.027 (0.014, 0.041)* | −0.010 (−0.021, 0.001) | −0.014 (−0.026, −0.003)* | −0.012 (−0.022, −0.002)* | −0.053 (−0.100, −0.007)* | −0.006 (−0.015, 0.003) | −0.002 (−0.010, 0.006) | −0.003 (−0.009, 0.003) |

| P‐value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.088 | 0.015 | 0.022 | 0.026 | 0.161 | 0.589 | 0.357 |

| Observations | 30 727 | 30 727 | 30 727 | 29 182 | 29 775 | 24 141 | 30 438 | 31 243 | 31 250 |

| Mean | 0.63 | 0.22 | 0.44 | 0.23 | 0.57 | 7.19 | 0.78 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

Sample restricted to first‐time parents aged 20‐44 years with a live birth between 2009 and 2017. Linear regressions controlled for individual‐level characteristics (age, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, month of delivery, survey language, survey method, and time since delivery) and state‐level characteristics (education, unemployment, median age, race, ethnicity, family planning programs, and contraceptive mandate). All regressions were estimated using the weights provided by the Center for Disease Control in the PRAMS data.

Abbreviations: CI, 95% confidence interval; ppt, percentage points.

P‐value < 0.05.

Source: Authors’ analysis of PRAMS data pooled from Phase 6 (2009‐2011), Phase 7 (2012‐2015), and Phase 8 (2016‐2017).

In addition to increases in preconception insurance coverage, higher levels of Medicaid generosity were also associated with reductions in unintended pregnancies. Among individuals with a high‐school degree or less, a 10‐ppt increase in Medicaid generosity was associated with a 1.2‐ppt decline in the proportion of pregnancies that were unintended (P =0.022). While point estimates suggest a negative association for the full sample, no statistically significant effects were found (coefficient: −0.004; P =0.125).

In addition, higher levels of Medicaid generosity were associated with declines in the proportion of first‐time parents reporting stress from bills in the year before delivery. Among individuals with a high‐school degree or less, a 10‐ppt increase in Medicaid generosity was associated with a 1.4‐ppt decline in stress due to bills (P =0.015). However, results were not statistically significant for the full sample.

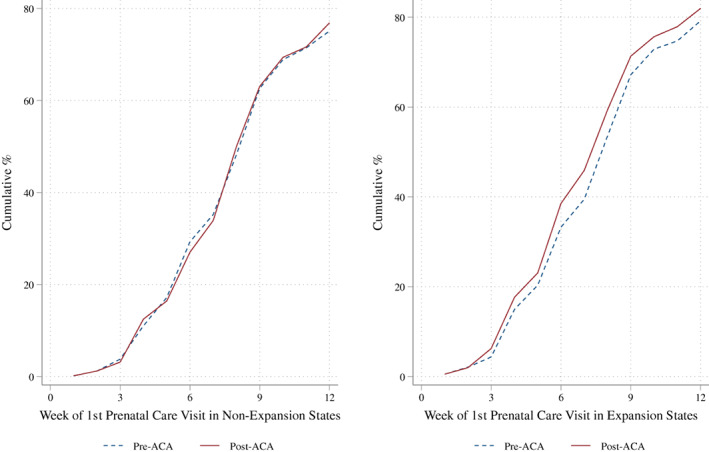

No statistically significant association was found between the Medicaid generosity index and initiation of prenatal care within the first trimester. However, among individuals with a high‐school degree or less, a 10‐ppt increase in Medicaid generosity was associated with initiating prenatal care 0.053 weeks earlier in the first trimester (P =0.026) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Week of first prenatal care visit in first trimester among individuals with a high‐school degree or less. Note: Figure includes the cumulative percent of first‐time parents with a high‐school degree or less who reported initiating prenatal care by week of pregnancy. Expansion states include those states that covered childless adults by 2014 or earlier. Nonexpansion states include states that did not provide any coverage for childless adults during the study period. Pre‐ACA includes births with a preconception period (one year prior to date of delivery) prior to 2014 and post‐ACA includes births with a preconception period after 2014

Finally, there was no significant association between Medicaid generosity and a diagnosis of either high blood pressure or diabetes before or during pregnancy.

3.3. Sensitivity analyses

In the sensitivity analyses, we found no significant association between the Medicaid generosity index and overall birth rates. In addition, we did not find any evidence of pretrends among most of our outcomes and there was no evidence of changes in outcomes in the placebo tests among individuals with higher incomes. Finally, the Medicaid generosity index was not associated with the inclusion of states in each year. Results from the sensitivity analyses are included in Appendix S2.

4. DISCUSSION

Using a national sample of first‐time parents who gave birth between 2009 and 2017, this study found that higher levels of Medicaid generosity were associated with significant, yet modest, increases in insurance coverage in the critical period before pregnancy. These increases in preconception insurance coverage were larger among individuals with a high‐school degree or less, the subsample most likely to be eligible for Medicaid. 35 Among this vulnerable group, we also found that increases in Medicaid generosity for childless adults were associated with declines in unintended pregnancies, reductions in stress from bills, and modestly earlier initiation of prenatal care; however, there were no changes in diagnoses of diabetes or high blood pressure.

Insurance coverage in the preconception period is a recommended approach to ensuring access to health care services and addressing modifiable risk factors in the critical preconception and early prenatal period. 6 , 7 Our results are consistent with recent studies demonstrating that Medicaid expansions for childless adults increased rates of preconception Medicaid coverage. 24 , 25 However, our study builds on this evidence by incorporating additional years of data, focusing on childless adults who were most likely to benefit from the expansions, and considering the variation in both the timing and size of the Medicaid expansion. In contrast to the recent research, we find that Medicaid generosity is also associated with increases in preconception insurance overall.

Our results for childless adults are also consistent in magnitude with prior research which found that increasing Medicaid eligibility for parents prior to 2012 was associated with increases in both Medicaid and overall preconception insurance coverage among multiparous individuals. 28 However, our study found smaller increases in coverage compared with recent research on Medicaid expansions among women of reproductive age. 22 , 37 In our study, an increase from 0% to 138% of FPL translates to a 34‐ppt increase in the generosity index, which is associated with only a 9.2‐ppt increase in Medicaid coverage among individuals with a high‐school degree or less. Our smaller increase in coverage is likely due the fact that we did not limit our sample to individuals in poverty who would be more likely to be eligible for Medicaid. In addition, while our study found that gains in insurance coverage were driven by increases in Medicaid, it is important to note that half of the increase in Medicaid was offset by declines in private/other insurance. This is consistent with there being some “crowd out” associated with Medicaid expansions, as individuals substitute Medicaid in place of other types of coverage. 38 This shift toward Medicaid from private/other insurance in the preconception period may be beneficial for first‐time parents due to the lower cost sharing and more comprehensive benefit packages in Medicaid, which could reduce barriers to care. 38

This study also found that higher levels of Medicaid generosity were associated with declines in the proportion of pregnancies that were unintended among individuals with a high‐school degree or less. These findings are consistent with prior evidence that increases in insurance coverage are associated with improvements in access to health care services, including family planning and contraceptives. 39 , 40 , 41 With a total of 251 963 births to first‐time parents with a high‐school degree or less, the average 18‐ppt increase in Medicaid generosity translates to an estimated 5503 fewer unintended births in the 43 PRAMS states in 2017. This reduction in the share of pregnancies that were unintended has important implications for maternal outcomes; individuals with unintended pregnancies are more likely to access prenatal care later, smoke and drink during pregnancy, and report postpartum depression. 42 Despite the reduction in unintended pregnancies, we found that Medicaid generosity was not associated with any significant changes in the overall birth rate, consistent with prior research. 43 A small decline in the birth rate from a 1.2‐ppt decline in unintended births is within the 95% confidence interval and, thus, it is possible that either the change in birth rates was too small to detect or there was no change in births and individuals were less likely to report a pregnancy as unintended.

Our finding that Medicaid expansions for childless adults are not associated with increases in the initiation of prenatal care within the first trimester is consistent with recent literature. 15 However, prenatal care within the first trimester is already high at 88%. 15 We do find that Medicaid expansions were associated with a very small but significant shift toward initiating care earlier in the first trimester among individuals with a high‐school degree or less. This very modest shift toward earlier prenatal care is consistent with guidelines that recommend initiation of prenatal care in the first eight to ten weeks of pregnancy, since a visit at twelve weeks is often too late to initiate effective interventions to prevent poor pregnancy outcomes. 42 However, a 34‐ppt increase in the Medicaid generosity index corresponds to a 1.4 day shift to earlier prenatal care, which is likely not clinically significant. Although these findings suggest that increasing Medicaid generosity may increase individuals’ connections with the health care system and enable them to enter into care sooner, there are other individual and structural factors, such as knowledge of prenatal care and clinic location, that must be also addressed in order to improve access to early prenatal care. 44

Despite the increases in preconception insurance coverage and shift to earlier prenatal care, we did not find any significant changes in diagnoses of diabetes or high blood pressure. Increasing insurance coverage and access to care just before and early in pregnancy may be too late to address risk factors for these conditions, including obesity. 12 , 13 However, increasing access to preconception and prenatal care may help individuals better control these conditions and prevent poor pregnancy outcomes. 12 , 13 , 45

Finally, this study found reductions in stress from bills before and during pregnancy among individuals with a high‐school degree or less. While prior research has found that Medicaid expansions have been associated with reductions in problems paying bills and improvements in households’ financial health, this is the first study to find that increasing Medicaid generosity is associated with improvements in finances for new mothers. 16 , 46 This reduction in stress from bills in before and during pregnancy is particularly important due to the association between stress and poor pregnancy outcomes as well as later life outcomes for children. 17 , 47 , 48

This study has several limitations. First, most of our study outcomes are from self‐reported survey data, which provide richer information on pregnancy than birth certificates or administrative claims data but may introduce bias for some variables. While studies comparing PRAMS with birth certificates have found responses for source of payment for delivery were highly reliable, less is known about the reliability of questions such as pregnancy intention, which may be impacted by recall and social desirability biases. 49 However, research has found little evidence that pregnancy intention is impacted by recall bias. 50 In addition, in the free text for “other” types of insurance, some individuals reported the name of Medicaid managed care plans, which may increase the proportion of individuals who report private/other insurance relative to Medicaid. Therefore, we combine all types of coverage to analyze the proportion of individuals with any insurance. This study was also unable to analyze the important outcome of preconception health care use because these questions were not asked consistently across all three survey phases.

In addition, the PRAMS data do not include all states, and not all states are included in every year. If inclusion in the data was associated with changes in Medicaid eligibility, then this could potentially bias the results. However, in the sensitivity analyses there was no significant association between the generosity index and the inclusion of the state in the data (Appendix S2: Table S8). The lack of data from all states may also limit the generalizability of the results. PRAMS does not include several large states such as California and multiple states in the South. However, PRAMS is representative of over 80% of all live births. 51

Finally, while the use of the generosity index improves upon prior literature, which often either does not take into account the variation in the size and timing of expansions or drops states from the sample, the index may not capture all relevant time‐varying policy changes. During the study period, many aspects of the health care system were changing which may bias the results; however, in the placebo tests among individuals with higher incomes who were less likely to be impacted by changes in Medicaid eligibility, the results were not significant (Appendix S2: Table S9). In addition, the Medicaid generosity index only captures the fraction of individuals who are expected to be eligible for Medicaid and does not reflect changes in the uptake of Medicaid. Additional research is needed to understand Medicaid uptake in the preconception period. Furthermore, there were small changes in Medicaid eligibility limits for pregnant individuals during our study period. However, many of our outcomes occur prior to conception and should not be impacted by changes in eligibility limits for pregnant individuals.

This study finds that increases in Medicaid generosity both before and after the ACA were associated with increases in insurance coverage and earlier initiation of prenatal care, as well as reductions in unintended pregnancies and stress from bills. Despite the gains in insurance coverage observed in this study, 14.3% of all first‐time parents who gave birth in 2017 still reported having no insurance in the month before conception and rates were twice as high among individuals with a high‐school degree or less. In addition, 42.2% of births to first‐time parents in 2017 were unintended. Increasing Medicaid generosity in the remaining states that do not provide coverage for childless adults may offer benefits for low‐income individuals and potentially help address the high rates of poor maternal outcomes.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

Appendix S2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This article was conceived and drafted while Caroline Geiger was a PhD candidate at Harvard University, and the findings and views in this article do not reflect the official views or policy of Genentech, Inc. Dr Sommers is currently on leave from Harvard and serving in the US Department of Health and Human Services. However, this article was conceived and drafted while Dr Sommers was employed at the Harvard School of Public Health, and the findings and views in this article do not reflect the official views or policy of the Department of Health and Human Services. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE1745303. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Geiger CK, Sommers BD, Hawkins SS, Cohen JL. Medicaid expansions, preconception insurance, and unintended pregnancy among new parents. Health Serv Res. 2021;56:691–701. 10.1111/1475-6773.13662

REFERENCES

- 1. Kassebaum NJ, Barber RM, Dandona L, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775‐1812. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31470-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hoyert DL, Miniño AM. National Vital Statistics Reports Volume 69, Number 2 January, 2020 Maternal Mortality in the United States: Vol 69. 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/severematernalmorbidity.html. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- 4. Milder S, Kenealy J, Honors MA, Eckstein T. Abstract P318: wide state‐by‐state variation in maternal mortality and chronic diseases that contribute to pregnancy complications. Circulation. 2017;135:AP318. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Admon LK, Winkelman TNA, Moniz MH, Davis MM, Heisler M, Dalton VK. Disparities in chronic conditions among women hospitalized for delivery in the United States, 2005–2014. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(6):1319‐1326. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Society for Reproductive Medicine; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Gynecologic Practice . Prepregnancy counseling. Fertil Steril 2019;111(1):32‐42. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Center for Disease Control and Prevention . Preventing Pregnancy‐Related Deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal‐mortality/preventing‐pregnancy‐related‐deaths.html. Accessed February 25, 2020.

- 8. Floyd RL, Johnson KA, Owens JR, Verbiest S, Moore CA, Boyle C. A national action plan for promoting preconception health and health care in the United States (2012–2014). J Women's Heal. 2013;22(10):797‐802. 10.1089/jwh.2013.4505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aztlan‐James EA, McLemore M, Taylor D. Multiple unintended pregnancies in U.S. women: a systematic review. Womens Heal Issues. 2017;27(4):407‐413. 10.1016/j.whi.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann. 2008;39(1):18‐38. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00148.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sommers BD, Gawande AA, Baicker K. Health insurance coverage and health — What the recent evidence tells us. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(6):586‐593. 10.1056/NEJMsb1706645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology . Preeclampsia and High Blood Pressure During Pregnancy. https://www.acog.org/patient‐resources/faqs/pregnancy/preeclampsia‐and‐high‐blood‐pressure‐during‐pregnancy. Accessed July 24, 2020.

- 13.American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(2):e49‐e64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14. American Academy of Family Physicians . Preconception care (position paper). Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(6):508‐510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clapp MA, James KE, Kaimal AJ. Preconception Insurance and Initiation of Prenatal Care. J Perinatol. 2019;39(2):300‐306. 10.1038/s41372-018-0292-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brevoort KP, Grodzicki D, Hackmann MB. Medicaid and financial health. NBER Working Paper 24002. 2017. 10.2139/ssrn.3063326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Strutz KL, Hogan VK, Siega‐Riz AM, Suchindran CM, Halpern CT, Hussey JM. Preconception stress, birth weight, and birth weight disparities among US women. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):e125‐e132. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. D'Angelo DV, Le B, O'Neil ME, et al. Patterns of health insurance coverage around the time of pregnancy among women with live‐born infants‐‐pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 29 states, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2015;64(4):1‐19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hillemeier MM, Weisman CS, Chase GA, Dyer AM, Shaffer ML. Women's preconceptional health and use of health services: Implications for preconception care. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(1 P1):54‐75. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00741.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaiser Family Foundation . Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision. https://www.kff.org/health‐reform/state‐indicator/state‐activity‐around‐expanding‐medicaid‐under‐the‐affordable‐care‐act/. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- 21. Daw JR, Sommers BD. The affordable care act and access to care for reproductive‐aged and pregnant women in the United States, 2010–2016. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(4):565‐571. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnston EM, Strahan AE, Joski P, Dunlop AL, Adams EK. Impacts of the affordable care act's medicaid expansion on women of reproductive age: differences by parental status and state policies. Womens Heal Issues. 2018;28(2):122‐129. 10.1016/j.whi.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McMorrow S, Kenney G. Despite progress under the ACA, many new mothers lack insurance coverage. Health Aff. 2018;19. 10.1377/hblog20180917.317923. Accessed November 1, 2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Clapp MA, James KE, Kaimal AJ, Daw JR. Preconception coverage before and after the affordable care act medicaid expansions. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(6):1394‐1400. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Myerson BR, Crawford S, Wherry LR. Medicaid expansion increased preconception health counseling, folic acid intake, and postpartum contraception. Health Aff. 2020;39(11):1883‐1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shulman HB, D'Angelo DV, Harrison L, Smith RA, Warner L. The pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS): overview of design and methodology. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1305‐1313. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaiser Family Foundation . Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Parents, 2002‐2020. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state‐indicator/medicaid‐income‐eligibility‐limits‐for‐parents/. Accessed January 1, 2021.

- 28. Wherry LR. State Medicaid expansions for parents led to increased coverage and prenatal care utilization among pregnant mothers. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(5):3569‐3591. 10.1111/1475-6773.12820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cutler DM, Gruber J. Does public insurance crowd out private insurance? Q J Econ. 1996;111(2):391‐430. 10.2307/2946683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Currie J, Gruber J. Saving babies: the efficacy and cost of recent changes in the Medicaid eligibility of pregnant women. J Polit Econ. 1996;104(6):1263‐1296. 10.1086/262059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sommers BD, Arntson E, Kenney GM, Epstein AM. Lessons from early Medicaid expansions under health reform: interviews with Medicaid officials. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2013;3:4. 10.5600/mmrr.003.04.a02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. NVSS ‐ Revisions of the U.S. Standard Certificates and Reports. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/revisions‐of‐the‐us‐standard‐certificates‐and‐reports.htm. Accessed July 6, 2020.

- 33. National Center for Health Statistics . User Guide to the 2011 Natality Public Use File. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Colin Cameron A, Gelbach JB, Miller DL. Bootstrap‐based improvements for inference with clustered errors. Rev Econ Stat. 2008;90(3):414‐427. 10.1162/rest.90.3.414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaiser Family Foundation . Medicaid's Role for Women. https://www.kff.org/womens‐health‐policy/fact‐sheet/medicaids‐role‐for‐women/. Published 2019. Accessed February 25, 2020.

- 36. Berkeley Labor Center U . Modified Adjusted Gross Income under the Affordable Care Act. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Margerison CE, MacCallum CL, Chen J, Zamani‐Hank Y, Kaestner R. Impacts of Medicaid Expansion on health among women of reproductive age. Am J Prev Med. 2019;58(1):1‐11. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guth M, Garfield R, Rudowitz R. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: updated findings from a literature review. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/the‐effects‐of‐medicaid‐expansion‐under‐the‐aca‐updated‐findings‐from‐a‐literature‐review/. Accessed April 21, 2021.

- 39. Sommers BD, Chua KP, Kenney GM, Long SK, McMorrow S. California's early coverage expansion under the affordable care act: A county‐level analysis. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(3):825‐845. 10.1111/1475-6773.12397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moniz MH, Kirch MA, Solway E, et al. Association of access to family planning services with Medicaid expansion among female enrollees in Michigan. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4):e181627. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ghosh A, Simon K, Sommers BD. The effect of state Medicaid expansions on prescription drug use: evidence from the affordable care act. Natl Bur Econ Res Work Pap Ser. 2017;No. 23044. 10.3386/w23044 [DOI]

- 42. Kilpatrick SJ, Papile L‐A, Macones GA, et al. Guidelines for Perinatal Care. Am Acad Pediatrics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Palmer M. Does publicly subsidized health insurance affect the birth rate? South Econ J. 2020;87(1):70‐121. 10.1002/soej.12436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Phillippi JC. Women's perceptions of access to prenatal care in the United States: a literature review. J Midwifery Women's Heal. 2009;54(3):219‐225. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bartha JL, Martinez‐Del‐Fresno P, Comino‐Delgado R. Early diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus and prevention of diabetes‐related complications. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;109(1):41‐44. 10.1016/S0301-2115(02)00480-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McMorrow S, Kenney GM, Long SK, Goin DE. Medicaid expansions from 1997 to 2009 increased coverage and improved access and mental health outcomes for low‐income parents. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(4):1347‐1367. 10.1111/1475-6773.12432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dunkel Schetter C, Tanner L. Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: implications for <others, children, research, and practice. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(2):141‐148. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wadhwa PD, Entringer S, Buss C, Lu MC. The contribution of maternal stress to preterm birth: issues and considerations. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38(3):351‐384. 10.1016/j.clp.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ahluwalia IB, Helms K, Morrow B. Assessing the validity and reliability of three indicators self‐reported on the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system survey. Public Health Rep. 2013;128(6):527‐536. 10.1177/003335491312800612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kost K, Lindberg L. Recall Bias in Women's and Men's Reports of Pregnancy Intentions in the National Survey of Family Growth. In: 2016 Annual Meeting. PAA; 2016.

- 51. Center for Disease Control and Prevention . Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System. https://www.cdc.gov/prams/index.htm. Accessed July 17, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Appendix S2