Abstract

Background

Quality care is essential for improving maternal and newborn health. Low- and middle-income Pacific Island nations face challenges in delivering quality maternal and newborn care. The aim of this review was to identify all published studies of interventions which sought to improve the quality of maternal and newborn care in Pacific low-and middle-income countries.

Methods

A scoping review framework was used. Databases and grey literature were searched for studies published between January 2000 and July 2019 which described actions to improve the quality of maternal and newborn care in Pacific low- and middle-income countries. Interventions were categorised using a four-level health system framework and the WHO quality of maternal and newborn care standards. An expert advisory group of Pacific Islander clinicians and researchers provided guidance throughout the review process.

Results

2010 citations were identified and 32 studies included. Most interventions focused on the clinical service or organisational level, such as healthcare worker training, audit processes and improvements to infrastructure. Few addressed patient experiences or system-wide improvements. Enablers to improving quality care included community engagement, collaborative partnerships, adequate staff education and training and alignment with local priorities.

Conclusions

There are several quality improvement initiatives in low- and middle-income Pacific Island nations, most at the point of health service delivery. To effectively strengthen quality maternal and newborn care in this region, efforts must broaden to improve health system leadership, deliver sustaining education programs and encompass learnings from women and their communities.

Keywords: Quality care, Quality improvement, Maternal health, Neonatal health, Pacific, LMIC, Scoping review

Summary.

Improving outcomes and healthcare experiences for mothers and newborns in the Pacific requires a whole of health system approach to embrace comprehensive, effective and sustainable ways to improve health care quality. A number of quality improvement initiatives exist in low- and middle-income Pacific Island nations, most of which focus on the point of health service delivery. To effectively strengthen the quality of maternal and newborn care in this region, these efforts must be broadened to encompass learnings from women and their communities, sustaining education programs and improving health system leadership. There is a need for more initiatives at either end of health service delivery - the health system and end user – in addition to initiatives which value the importance of the healthcare experience for women and babies.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Global maternal and newborn mortality remain unacceptably high in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), including most countries in the Pacific region [1]. The majority of maternal and newborn deaths occur at birth or within the first 24 h of life and in LMICs [1]. Pacific Island LMICs experience a significant burden of preventable maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality, and face considerable challenges in optimising the quality of care for mothers and babies [2]. With skilled birth attendance (SBA) rates over 80% across most Pacific Island Nations - with the exception of Papua New Guinea (PNG) at 40% – the Pacific is an example of how relatively high healthcare provider coverage alone does not necessarily equate to better maternal and newborn health [3,4].

It is increasingly recognised that in order to effectively improve health outcomes for mothers and babies, health systems need to focus on achieving quality care [5,6]. Quality care is health care which is safe, effective, timely, efficient, equitable and people-centred [7]. It is estimated that improvements in the quality of facility care, including preconception, antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care, for mothers and babies could prevent approximately 113,000 maternal deaths, 531,000 stillbirths and 1.3 million neonatal deaths each year [8] .The Sustainable Development Goals, particularly in relation to Good Health and Wellbeing (Goal 3) and Gender Equality (Goal 5), will not be achieved unless health systems recognise quality care as a fundamental tenet and basic obligation of every health system [5]. In 2016, the World Health Organization published a set of standards to provide facilities with a framework for improving the quality of care for mothers and newborns [9].

Many small island nations in the Pacific are characterised by over-strained and under-resourced health systems, health workforce shortages, high aid dependency, infrastructure limitations and challenging geography across land and sea [10,11]. These are all barriers to achieving quality maternal and newborn care across the Pacific. Gaps exist in available reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health services, including low antenatal care attendance and high unmet family planning needs. High rates of preterm birth, sexual reproductive tract infections, teenage pregnancy and gender-based violence are further challenges [12,13]. This situation leads to increased maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality and impacts on efforts to improve quality of care [14]. Pacific Island nations are also especially susceptible to the social, economic and health impacts of climate change [15,16].

Despite a 25-year commitment to ‘Healthy Islands’ driven by the World Health Organization (WHO), health systems in the Pacific struggle to provide equitable coverage with quality care [17,18]. There is a particular lack of evidence regarding the actions taken by LMICs in the Pacific region to achieve quality maternal and newborn care. To our knowledge, no previous scoping reviews have systematically examined quality improvement (QI) efforts implemented in Pacific LMICs. The aim of this scoping review was to collate, analyse and categorise health system QI efforts that aimed to improve the quality of maternal and newborn care in LMICs in the Pacific region, and summarise major findings from these studies.

2. Methods

A scoping review approach was chosen to due to the broad nature of quality maternal and newborn care interventions and the need to identify and map the existing literature [19,20]. The scoping review framework by Levac et al. [21] informed the review process. The PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [22] and the Joanna Briggs Institute Methodology for Scoping Reviews were also referred to for methodological considerations [19].

An expert advisory group of six leading maternal and child health clinicians and researchers across the Pacific region was established to provide advice and guidance throughout the scoping review process. Members of the advisory group were from Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, PNG and Solomon Islands. The group provided input and feedback regarding the appropriateness of the research question, inclusion and exclusion criteria, suitability of the data extraction tool and synthesis and interpretation of the research findings.

Eligible publications were those describing a QI intervention aimed at improving maternal and newborn care. A QI intervention was deemed to be any activity undertaken to improve the quality of maternal and newborn care at a health system, service delivery or end-user level. Publications had to be based in one or more of the 16 Pacific LMICs (as defined by the World Bank in 2019 [23]) – PNG, Palau, Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, Fiji, Kiribati, Samoa, Tokelau, American Samoa, Cook Islands, Niue and Tonga. Multiple study designs were eligible as long as primary data were available, including: randomised controlled trials and non-randomised controlled trials, controlled before-after studies, interrupted time series studies and repeated measured studies; before-after studies; retrospective and prospective cohort studies; other quasi-experimental designs; program evaluations; protocols and qualitative studies. Case reports and other project reports were also included.

Publications in a language other than English and prior to the year 2000 – to ensure findings are relevant to current policy and practice - were excluded [23]. Commentaries, letters to the editor and editorials were also excluded.

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

Four databases were searched for primary studies based on the criteria presented above: MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE (OVID), Maternity and Infant Care (OVID), and the WHO Global Health Library (GHL). In the WHO GHL database, the West Pacific Index Medicus (WPIM/WPRO) was specifically included. The search strategy and key search terms used are outlined in Appendix 1.

Table A1.

Search strategy.

| Concept A | Pregnancy and childbirth | |

|---|---|---|

| MEDLINE | Subject headings (MeSH) | pregnancy/ or pregnant women/ or gravidity/ or parturition/ or prenatal care/ or postpartum period/ or postnatal care/ or pregnancy outcome/ or labour or labor, obstetric/ or delivery, obstetric/ or obstetrics/ or infant care/ or perinatal care/ or maternal health services/ or maternal-child health services/ or womens health services/ or infant mortality/ or maternal mortality/ or maternal death/ or child health services/ or pregnancy complications/ or reproductive health services/ |

| EMBASE | Subject headings | pregnancy/ or birth/ or prenatal Care/ or childbirth/ or natural childbirth/ or obstetric delivery/ or puerperium/ or postnatal care/ or newborn care/ or child health care/ or newborn/ or labour/ or labour management/ or vaginal delivery/ or child health/ or perinatal care/ or perinatal period/ or maternal care/ or maternal health care/ or pregnant woman/ |

| MEDLINE, EMBASE | Text words | (maternal health or newborn health).mp. or (maternal adj2 child health).mp. or (maternity care).mp. or ((newborn* or infan*) adj2 (care)).tw. or (intrapartum or intra partum or delivery or birth or labour or obstetric care or caesarean or vaginal delivery).mp. or (pregnan* or matern* or gestation* or antenatal or prenatal or perinatal or peri natal or peri-natal or postnatal or post-natal or postpartum or post partum or post-partum or natal or gravidit* or gravida* or multigravid* or primigravid* or parturition or nullip* or multip*).mp. or (expectant adj (mother* or wom#n or female* or girl*)).mp. |

| Concept B | Pacific Island Nations | |

| MEDLINE | Subject headings (MeSH) | exp pacific islands/ or exp melanesia/ or exp micronesia/ |

| EMBASE | Subject headings | exp pacific ocean/ |

| MEDLINE, EMBASE | Text words | (American Samoa* or Cook Island* or Federated States Micronesia* or Fiji* or Kiribati* or Marshall Islands* or Nauru* or Niue* or Palau* or Papua New Guinea* or PNG* or Samoa* or Solomon Island* or Tokelau* or Tonga* or Tuvalu* or Vanuatu*).mp. or (melanesia* or micronesia* or polynesia*).mp. or (Pago Pago* or Rarotonga* or Avarua* or Palikir* or Suva* or Tarawa* or Majuro* or Yaren* or Alofi* or Ngerulmud* or Port Moresby or Apia or Honiara or Atafu* or Nuku*alofa or Port Vila*).mp. |

| Concept C | Quality care | |

| MEDLINE | Subject headings (MeSH) |

Quality of Health Care/ or Quality Improvement/ or Quality Indicators, Health Care/ or Clinical Audit/ or Medical Audit/ or Near Miss, Healthcare/ or Quality indicator, Healthcare/ or Delivery of Health Care/ or Health Services Accessibility/ or Attitude of health personnel/ or Health knowledge, attitudes, practice/ or Health Resources/ or Health Workforce/ or Health Services/ or Patient satisfaction/ |

| EMBASE | Subject headings | Health care quality/ Benchmarking/ Clinical effectiveness/ Clinical indicator/ Health care survey/ Medical error/ Patient attitude/ Patient satisfaction/ Practice gap/ Practice guideline/ Program evaluation/ Public health systems research/ |

| MEDLINE, EMBASE | Text words | Quality.tw. (Quality of care).tw. (Program evaluation or benchmarking or clinical audit or medical audit or nursing audit or near miss or close call*or quality improvement or quality indicator* or standard* of care).mp. (health facilit* or health workforce or health service* or birthing cent* or health personnel or health services administrat*).mp. (health care quality or health care access or health care evaluation).mp. |

Reference lists of key included items were hand-searched to identify other relevant articles. Grey literature was obtained from direct searches using key phrases ‘quality improvement’ and ‘maternal and newborn care’ and reviewing published reports. Websites searched included key non-government organisations (NGOs) and international organisations providing maternal and newborn services in the Pacific, including UNFPA, WHO, UNICEF, USAID, NZAID, AUSAID, Population Services International, and Pacific Open Learning Health Network. Websites of national Ministries of Health for all included countries were also searched directly for eligible documents.

All citations were imported into Endnote and duplicates removed. Remaining citations were imported into Covidence [24] for initial screening and full text review independently by two reviewers (AW and NS). Disagreements were resolved through discussion or involvement of a third reviewer (CH). Data extraction was performed on included studies using Microsoft Excel (AW and GH). The methodological quality of each study was assessed by two investigators (AW and GH) using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [25] where applicable. Where scores differed, discrepancies were discussed and resolved. The MMAT allows for simultaneous quality appraisal of multiple study types including qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies and hence was appropriate for this review [26]. Not all eligible studies and reports provided sufficient information to fully appraise quality using the MMAT. Quality scores were not used to include or exclude studies, but instead used to describe the quality of available evidence, as part of the mapping component of a scoping review. A four-level health system framework [27] and the eight domains from the WHO standards for Improving Quality of Maternal and Newborn Care in Health Facilities (2016) [9] were used to categorise identified interventions. A descriptive numerical summary and thematic analysis were undertaken to collate and summarise the data [21].

3. Results

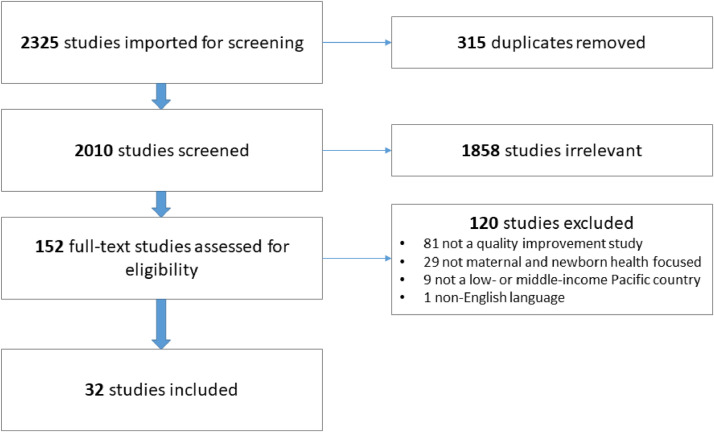

The search was conducted between 28 and 30 July 2019. Collectively, the searches yielded a total of 2325 records (7 from grey literature), 315 of which were duplicates (Fig. 1). Of the remaining 2010 unique citations screened, 1858 did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. A further 120 citations were excluded at full text review, as they either did not describe actions to improve the quality of maternal and newborn care (N=110), were not based in an included country (N=9) or published in a language other than English (N=1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram.

In total, 32 studies were included (Fig. 1). Table 1 presents a descriptive summary of the included studies. Of these, most (63%) were from PNG, 19% described initiatives that spanned several Pacific nations, 12% from Fiji and the rest from Samoa and the Solomon Islands. Fourteen papers (44%) were program evaluations, 7 (50%) of these used mixed methods approaches. Eight of the papers (25%) were descriptive studies, of which over 50% used qualitative methods. Two brief reports, one before and after study, one protocol and one case series were also included. The remaining five papers were regional strategy reports, action plans and progress reviews. No randomised trials were identified. Of all the research study papers reviewed (23 of the 32 included papers), mixed research methods were the most common (11, 48%) followed by qualitative (7, 30%) and quantitative approaches (5, 22%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Authors | Year | Country | Description of project/aim | Study design | Methods | Major findings | Strengths | Limitations | MMAT scorea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashwell and Barclay [28] | 2009a | Papua New Guinea (PNG) | Women and Children's Health Project – aimed at increasing quality and coverage of rural health services to reduce maternal and infant mortality. Involved community development and health promotion. | Program evaluation | Mixed methods. Precede-Proceed model. Interviews and Focus Group Discussions. National, provincial and district level data. |

Donor-defined objectives and contractual obligations limit project activity and outcomes. Increased interactions between community and maternal child health services. Healthcare workers, community health organisations and district/provincial health administrators not adequately engaged in planning process. Raising awareness of maternal child health issues is not enough, need to provide community leaders with tools/process to address issues. Healthcare workers expected to mobile community without support or consideration of capacity to do this. Insufficient technical advice and local leadership. Project ‘scope’ modified and expanded with inclusion of foreign technical advisor but ongoing lack of local involvement/leadership. Project lacked alignment with existing health system levels. Lack of involvement of National Department of Health from the outset therefore impact on national policies and programs was limited. |

National, provincial and district level data included. | Model failed to sufficiently describe barriers to improving quality care. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 2 |

| Ashwell and Barclay [49] | 2009b | PNG | Women and Children's Health Project – aimed at increasing quality and coverage of rural health services to reduce maternal and infant mortality. Involved community development and health promotion. | Program evaluation | Mixed methods. Qualitative interviews, Focus Group Discussions, site visits, opportunistic observations of behaviours, health record audits. |

In villages where volunteers and staff had been trained - new health knowledge led to changes in lifestyle practices, improved physical health and social and emotional wellbeing. Factors influencing success were motivated community members who acted as a catalyst for change, empowered leadership through governance structures, effective visual tools, village health volunteers linking community and rural health workers. Factors limiting success were poor understanding of community development, limited information sharing, ‘top down’ approach to community development and weak community leadership. |

Large sample size, several different communities involved, follow up post project implementation sufficient to assess sustainability of project outcomes, broad spectrum of stakeholder perspectives included. | Limited quantitative data to support qualitative findings, unclear outcome measures, limited interviews with community members. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 2 |

| Bettiol [39] | 2004 | PNG | Village Birth Attendant (VBA) program trains women in small, rural PNG villages to be village birth attendants. | Program evaluation | Qualitative. Semi-structured interviews with VBAs. |

VBAs have many roles – maternal and child health patrols, antenatal checks and referrals, health promotion. VBAs were motivated to help mothers in community They faced difficulties managing obstetric complications i.e. breech, post-partum haemorrhage and logistical issues i.e. transport access. |

Methods well described and outcome data provided regarding VBA perspectives. | Perspectives and experiences from mothers who received care from village birth attendants not included. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 |

| Choy and Duke [40] | 2000 | PNG | Village community health worker and child health nurses training in maternal and child health for women from remote villages coordinated by Save the Children with Goroka Base Village hospital. | Program evaluation | Quantitative, community level data. | 30 Village community health workers and 25 child health nurses trained. Improvement in village child health worker knowledge including how to recognise a sick child, immunisation requirements, measure growth and infant and young child feeding recommendations. |

Strong rationale for program and data provided to highlight need, clear acknowledgement of limitations of the program. | Methods used to assess knowledge of health care workers unclear. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | N/A |

| Datta et al. [30] | 2013 | PNG | Development of National Action Plan for Elimination of Maternal and Neonatal tetanus in PNG. | Program evaluation | Quantitative descriptive (case study series). | Three cases of neonatal tetanus recorded in PNG in 2011 – 2 survived, 1 died. Al involved village births with untrained attendants, unhygienic cord care and no maternal tetanus vaccinations. National action plan involved national supplementary immunisation rollout – targeting women of child-bearing age (77% of eligible women reach in first round), training for midwives and CHWs around hygienic birth practices and antenatal care services. |

Sufficient data supplied to support case series reports, clear rationale for action plan, action plan appears appropriate for targeted outcomes. | Authors, funders and consultation process for development and implementation of action plan unclear. Limited data on measures of success, unclear methods for evaluation of vaccine program. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | N/A |

| Dawson [41] | 2016 | PNG | Maternal and Child Health Initiative – eight clinical midwifery facilitators placed in four midwifery training schools across PNG to train and mentor midwifery educators. | Program evaluation (first 2 years) | Mixed methods – focus group discussions, semi-structured interviews, regular site visits, meeting minutes, surveys, feedback surveys and assessment pieces. | Increased quantity and quality of midwifery graduates (enrolment numbers, knowledge, clinical skills, compassion towards patients). Increased capacity of midwifery educators and clinicians (Improved student academic results, improved clinical education experiences for students, better maternal and newborn outcomes i.e. neonatal sepsis rates decreased). Accreditation of midwifery curricula in all midwifery schools. Increased networking and collaboration between schools. |

Excellent methodology, study design and research questions. Mixed-methods approach and purposive sampling provided breadth and depth of insight. Involvement of a diverse stakeholders, monitoring and evaluation framework were underpinned by program logic model, substantial evaluation period (2 years). | Women's perspectives not included. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | N/A |

| Duke [32] | 2017 | PNG | Implementation of oxygen delivery systems. | Project protocol | Description of quality improvement (QI) project protocol. | Requires holistic systems approach. Expensive and time-consuming. Needs adequate community engagement. Limited by infrastructure issues (transport and terrain). Requires staff training. |

Study sites selected with key stakeholder consultation, clear research questions and outcome measures, metrics suitable for assessing outcome measures, comprehensive evaluation plan, comprehensive discussion about considerations for conducting implementation study. | Women and their families’ perspectives not included. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | N/A |

| Field [31] | 2018a | PNG | Community Mine Continuation Agreement Middle and South Fly Health Program aimed at improving health service delivery in remote PNG. | Program evaluation | Mixed methods – pre/post analysis of health service delivery indicators, semi-structured interviews with health workers and assessment of health facility equipment and infrastructure. | Rate of outpatients, outreach clinics, immunisation coverage, antenatal care coverage, all significantly improved with the program except family planning coverage (which improved but not significantly) and supervised births (which decreased despite health worker perceptions). Proportion of facilities with standard equipment, transport and lighting increased. Health worker training, especially obstetric training, was most commonly cited by health workers as leading to improved services. Main barriers included a lack of basic supplies, lack of supervision, lack of community support and cultural barriers that prevented people from accessing services. |

Program logic model created, comprehensive mixed methods study designed to triangulate results, appropriate measures taken to ensure accuracy of data when missing/unclear. | No information regarding whether health workers declined to be interviewed, women and their families’ perspectives not included. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 |

| Field [29] | 2018b | PNG | Rural Primary Health Services Delivery project – review development of national policies and standards, establishment of partnerships at provincial level with state and non-state partners in health; health worker training, infrastructure development through construction of two community health posts in each district and community-level health promotion activities to improve demand for services. | Program evaluation | Mixed methods (contextual analysis) – sequential explanatory design involving analysis of baseline quantitative indicator performance, followed up by semi-structured interviews with provincial health administrators. | Less than half of all included districts met the 2013 national target for each performance indicator (outreach clinics, measles vaccination coverage, supervised births). Large variation in performance indicators between and within project districts. Provincial Health Administrators perceived high performance to be influenced by accessibility of health facilities by road in urban areas, competent staff and health services operated by churches or private companies. Inadequate numbers of staff, poorly skilled staff, funding delays and challenging geography were major contributors noted for poor performance. |

Presentation of data by district rather than province enabled comparisons between districts within a province. Sequential explanatory approach strengthened quantitative data. | Data sourced from National Health Information System - issues with quality and completeness noted. Limited description of project. Only baseline data from first year of evaluation presented. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 |

| Gardiner [37] | 2016 | Fiji | IMproving Perinatal mortality Review and Outcomes Via Education (IMPROVE) programme – series of workshops designed to improve maternity providers knowledge of and confidence in the management of perinatal deaths. | Program evaluation | Mixed methods – pre/post program questionnaire. Knowledge, confidence and satisfaction post program. Open-ended questions to identify what aspects of the program participants found most and least useful and suggestions for improvement. | Proportion of Australian and international participants who were knowledgeable and confident regarding management of perinatal deaths increased from pre- to post- workshop for all items and stations (p<0.001). High degree of satisfaction (>90%) for the workshops both in Australia and internationally. In the international workshops, participants expressed a desire for more hands-on activities and slight adaptation of the program to align with local investigation and classification practices. Participants from middle-income countries felt that the material was relevant to their workplace and their goals for healthcare provision. |

Large sample size, delivery of program to a variety of relevant health professions. Inclusion of open-ended questions to enhance assessment of program and improve future delivery. | Long term follow-up of knowledge and confidence would be useful, no assessment of clinical outcomes. | 5 |

| Gupta [44] | 2017 | PNG | Spacim Pikinini - Implant outreach program coordinated by non-government organisations (NGOs), community leaders and health authorities. Local health workers trained in contraception counselling and implant insertion and removal techniques. | Program evaluation | Quantitative descriptive – cross sectional survey of women in two rural provinces who received a contraceptive implant 12 months prior. | 860 women who had had a contraceptive implant inserted 12 months prior were surveyed. 97% still had the device in situ, 95% were very happy with it, 76% reported no side effects. Irregular bleeding was the most reported side effect (20.6% of women) but only 7% said the bleeding was bothersome. A desire to have more children was the most common reason for removal of the implant. 92% of women indicated they would use the implant again in future. Around 50% of women acknowledged they had been discouraged from using the device by church members and/or fellow villagers but this was not a reported reason for removal. Documented failure rates were 0.8%. |

Large sample size. Comprehensive outline of project and methods. Included direct patient perspective. | Potential for over- and under-measurement of implant failure. Reliability of the data affected by recall bias given retrospective study. Only two rural provinces included, findings not generalisable to all of PNG. In addition, may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 |

| Kamblijambi [43] | 2017 | PNG | To examine a PNG University's Bachelor of Clinical Maternal and Child Health programme in respect to macro and micro knowledge and skill transferability to all stakeholders. | Program evaluation | Qualitative – curriculum analysis, interviews with graduates, focus groups with Village Birth Attendants (VBA) and Village Community Health Workers (VCHWs), face-to-face interviews with postnatal women (recipients of targeted VBA education). | Insufficient resources and program too short to meet objectives. Interviewees reported feeling well equipped with core theory and clinical knowledge but often felt unable to implement the knowledge gained in their work environment. Group learning considered particularly useful. Rural community placements had a positive influence on attitudes, behaviour and clinical practice of participants. Working in partnership with the community considered valuable. Participants considered assessment practices to be poor and would have preferred assessments that enabled knowledge retention and enhanced clinical skills acquisition and improvement. Participants felt the program had enhanced their career prospects. |

Inclusion of wide range of stakeholders. Content validity of interview guide was ensured through revision and conduction of a pilot study. Purposive sampling employed to ensure diversity of participant location and experience. |

Only phases 1 and 2 reported. No reporting of outcome measures related to morbidity, mortality or health practice implementation. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 |

| Kirby [48] | 2013 | PNG | Mother Baby Bundle Gift Program aims to encourage mothers to birth in health facilities. Program consists of mother and baby support packages, staff incentives, staff emergency obstetric and newborn care training and emergency supplies. Installation of waiting houses, solar lighting and water supplies are also included in the program. | Brief report | Data source not clear – analysis of outcome data for mothers and newborns. | Three health facilities included. Implementation of the Baby Bundle Gift Program resulted in 55-143% increase in supervised deliveries across all three facilities. No increase in complications. 2 maternal deaths over 10-month study period. |

Informed by survey of women in the village - prospective program recipient involvement in project design. Simple, relatively cheap intervention with impact. Comprehensive description of QI activity. | Intervention multi-pronged but results presented in a way which attributed all outcomes to the mother baby gift program. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 4 |

| Kirby [33] | 2015 | PNG | To identify causes of maternal mortality and identify appropriate and sustainable solutions in Milne Bay province. Also to review whether the Mother Baby Bundle Gift Program can prevent maternal deaths. |

Descriptive study | Mixed methods - Surveys and interviews with a focus on reviewing maternal deaths. Health care workers and family members asked to identify causes of maternal mortality and classification of factors according to a three-phases-of-delay model. |

31 maternal deaths identified from maternal mortality survey. 20 cases (65%) related to haemorrhage: postpartum haemorrhage (11), retained placenta (6) and antepartum haemorrhage (3). Other causes included sepsis, ectopic pregnancy, eclampsia, cerebrovascular accident, pneumonia and tuberculosis. Phase one delays (deciding to seek care) responsible for 80% of cases. MBG program was associated with increases in the number of supervised health centre births across all health centres. 3 maternal deaths in the village and 3 maternal deaths at health centres over the study period. |

All major health centres in the region included. Intervention targeted towards specific barriers to appropriate perinatal care in the region. | Short term follow-up. Intervention multi-pronged but results presented in a way which attributed all outcomes to the mother baby gift program. Value of program beyond individual province not discussed. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 |

| Mannering [73] | 2013 | Samoa | To evaluate the POINTS* education program to improve neonatal care from the perspective of neonatal nurses. *POINTS – pain management, optimal oxygenation, infection prevention, nutritional and temperature management, and supportive care. |

Brief report | Reports from neonatal nurses involved in the program. | Increase in neonatal nurse neonate. ‘5 moments of hand hygiene’ prominently displayed and promoted throughout unit. Increase in pain relief measures practised Improved developmental support for premature babies. Increased enthusiasm for neonatal education. Increased profile of neonatal nursing. |

Clear description of programme and outcomes. | Evaluation findings not included in the report, anecdotal reports of improvement only. Data collection processes unclear. | N/A |

| Moores [42] | 2016 | PNG | To explore the impact of strengthening midwifery education in PNG. | Descriptive study | Mixed methods - surveys, focus groups and interviews were via telephone phone or in person. | 89.3% of respondents were working as midwives, with an additional 3% working as midwifery or nursing educators. Graduates located in 21 of the 22 provinces of PNG, predominantly in urban areas with 41% working in rural areas. Most graduates felt that the theoretical, clinical and rural practice components of their education course had prepared them for their current clinical practice. |

|||

| Many felt they had improved basic midwifery skills and emergency obstetric skills, however some felt there were inadequate opportunities to acquire the necessary skills to feel competent and confident. Graduates exhibited increased skills acquisition and confidence, leadership in maternal and newborn care services and a marked improvement in the provision of respectful care to women. |

Large sample size. Almost all provinces included. Appropriate use of quantitative data to support qualitative findings. | Graduates working in remote areas not included. Limited outcome data (e.g. number of women giving birth at facilities, morbidity, mortality) and patient perspectives. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 | ||||||

| Narayan [34] | 2009 | Fiji | A report reviewing ten cases of neonatal Enterobacter aerogenes infections in a Fijian NICU and the measures implemented to prevent transmission and stop the outbreak. | Case series and description of QI activity | Examination of medical records, medical and microbiological tests, description of QI activity. | 10 of the 18 infants admitted to the unit in May 2007 developed septicaemia with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacter organisms. Three infants died. Infants ranged in age from 4 hours to 19 days. The most common reason for admission to the NICU was respiratory distress with premature birth. A communally used bag containing normal saline was deemed to be the source in all 10 cases. Three major issues were identified as contributing to the outbreak: poor adherence of physicians and nurses to hand hygiene protocol; prolonged use of normal saline and dextrose 10% bags and for multiple patients; infrequent disinfection of the IV rubber ports on fluid bags and lines before withdrawal and injection. Infection control measures introduced including simple hand hygiene, use of single-use vials of IV fluid bags and strict aseptic technique for injections - no new cases were identified after the implementation of these control measures. |

Identified contributing factors to outbreak and designed infection control measures targeted specifically towards the outbreak. Clear description of protocol. Ongoing monitoring of infection control compliance. |

Follow up period not specified. Sustainability of the program not discussed. Issues within one hospital may not reflect wider health system issues related to infection prevention and control. Fiji-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | N/A |

| O'Keefe [38] | 2011 | PNG | To evaluate the effectiveness of the East Sepik Women and Children's Village Health Volunteers program. | Before and after study | Quantitative – review of medical and health records. | In East Sepik province, the proportion of women receiving their first antenatal care visit from a village health volunteer increased from 6% in 2007 to 15% in 2010. Proportion of women whose childbirth was attended by a village health volunteer increased from 8% to 13.2%. Reported health facility coverage of women attending a health facility for childbirth decreased from 28% in 2007 to 22% in 2010. |

Large sample size, data cleaning performed before analysis in attempt to ensure accuracy, highlights contribution of village health worker to maternal and newborn care. | Potentially inaccurate population estimates – based on census data collected 9 years prior. Quantitative data only – limited ability to explain causes behind increased proportion of births attended. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 |

| Olita'a [74] | 2019 | PNG | To evaluate the safety and effectiveness of a protocol based on giving minimal or no antibiotics to well term babies born after premature rupture of membranes and its effect on neonatal sepsis at Port Moresby General Hospital in PNG. | Descriptive study (case report) | Quantitative. Data collected from medical records, clinical assessment and information provided by healthcare staff. | 133 babies born to mothers who had premature rupture of membranes were assessed at 7 days. Signs of sepsis occurred in 10 babies (7.5%; 95% CI 4.4% to 13.2%) in the first week. An additional four (3%) had any sign of sepsis between 8 and 28 days. There was one case of bacteraemia and no deaths. 37 were lost to follow-up, but hospital records did not identify any subsequent admissions for infection. Sepsis rates documented were found to be comparable with other studies in low-income countries. |

Used definition of neonatal sepsis in line with WHO recommendations (ie including clincial features). Use of different management protocol depending on mother's intrapartum antibiotic status. | No background information provided on previous sepsis rates in neonates. Study conducted in peri-urban setting with health centre and hospital access, limited generalisability across PNG. In addition, PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 3 |

| Raman [35] | 2015 | Fiji | Development and evaluation of a perinatal mortality audit system in 3 hospitals in Fiji. | Program evaluation | Mixed methods – perinatal audit data and key informant interviews. | 141 stillbirths and neonatal deaths were analysed from 2 hospitals (57 from hospital A and 84 from hospital B; forms from hospital C excluded because incomplete/illegible). 28 (49%) stillbirths were recorded in hospital A compared with 53 (63%) in hospital B. 82% of stillbirths from hospital A were due to a delay in receiving care. |

|||

| Factors that led to delays in receiving appropriate healthcare included patient; sociocultural and family; resource; social and human infrastructure; health system; care; and process factors. Substantial health system factors contributing to preventable deaths were identified, and included inadequate staffing, problems with medical equipment, and lack of clinical skills. Leadership, teamwork, communication, and having a standardised process were associated with increased uptake of perinatal mortality audit system. |

Perinatal mortality audit datasheet refined for use in Fiji. Mixed methods design - investigation of factors affecting success of perinatal mortality audit. Exploration of factors that led to delays in accessing appropriate health care. |

Most results derived from Hospital A (tertiary hospital, which could bias results). Incomplete data from Hospitals A and B. Fiji-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 | ||||||

| Rumsey [46] | 2016 | Cook Islands, Kiribati, PNG, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Vanuatu, Fiji, Nauru, Samoa, Tokelau, Tuvalu, Niue | To describe the experiences of 34 nursing and midwifery leaders in the South Pacific region who undertook the Australian Award Fellowship (AAF) program. | Descriptive study | Qualitative – semi-structured interviews (individually or in pairs). | Thirty-four nurses and midwives from 12 countries participated. Four main themes were identified: having a country-wide objective, learning how to be a leader, negotiating barriers and having effective mentorship. Participants had a good understanding of their country's needs and objectives for improvement of their health care and workforce and described positive learning experiences from involvement in the AAF program. Participants deemed their mentorship from country leaders highly valuable in relation to completing their projects, networking and role modelling. |

Inclusion of participants from multiple years of the program and a variety of countries. | Limited outcome data to determine if program translated into improved care. | 5 |

| Sa'avu [57] | 2014 | PNG | To understand the quality of care provided for care in five rural district hospitals in the highlands of PNG. | Descriptive study and protocol development | Quantitative (baseline assessment of quality of care provided) – structured survey forms, medical and admissions records, oxygen/electricity records. | Many district hospitals are run by under-resourced NGOs. Most hospitals had general wards in which both adults and children were managed together. Paediatric case numbers ranged between 232 and 840 patients per year with overall case-fatality rates (CFR) of 3–6% and up to 15% among sick neonates. Pneumonia accounts for 28–37% of admissions with a CFR of up to 8%. |

|||

| There were no supervisory visits by paediatricians, and little or no continuing professional development of staff. Essential drugs were mostly available, but basic equipment for the care of sick neonates was often absent or incomplete. Infection control measures were inadequate in most hospitals. Cylinders were the major source of oxygen for the district hospitals, and logistical problems and large indirect costs meant that oxygen was under-utilised. Multiple electricity interruptions, but hospitals had back-up generators to enable the use of oxygen concentrators. After 6 months in each of the five hospitals, high-dependency care areas were planned, oxygen concentrators installed, staff trained in their use, and a plan was set out for improving neonatal care. |

Detailed data obtained from reliable sources. Included plan for future QI improvement. | Unclear study design. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 4 | ||||||

| Sandakabatu [36] | 2018 | Solomon Islands | To evaluate a new child mortality review process introduced at the National Referral Hospital, Honiara, Solomon Islands. | Program evaluation | Mixed methods – audit data from clinical records and observations of audit meetings. | 33 child mortality review meetings were conducted over 6 months, reviewing 66 neonatal and child deaths. Areas for improvement included use of systematic classification of causes of death, inclusion of social risk factors and community problems in the modifiable factors and more follow-up with implementation of action plans. To avoid preventable deaths, greater emphasis needed with communication, clinical assessment and treatment, availability of laboratory tests, antenatal clinic attendance and equipment for high dependency neonatal and paediatric care. Causes of deaths were classified, although there was a need among health workers to clarify what constitutes an immediate and underlying cause of death, as there was overlap. Classification of modifiable factors was performed, but it was identified that there was a lack of consideration for social risks and community-based factors. |

Sufficient study duration to assess change over time. Suggestions to improve the audit process offered. | Mortality cases often discussed many weeks/months after event, potentially affecting recall. Solomon Islands-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 |

| Thiessen [47] | 2018 | PNG | To evaluate facilitators and barriers to effectiveness of a Public Private Partnership (PPP) funded Reproductive Health Training Unit (RHTU) in PNG. | Descriptive study | Qualitative – interviews with key stakeholders. | Features of the PPP that enabled the RHTU to be more effective included understanding and agreeing with national plan for PPPs and maternal child health, strong champions & strong relationships with decision making bodies and creating autonomy and branding. Features of the PPP that created barriers to the effectiveness of the RHTU included lack of governance leading to confused decision making and roles & responsibilities, differing institutions, cultures and ownership struggles, lack of capacity within institutes especially National Department of Health. |

Large number of stakeholders interviewed (85) from range of disciplines, participants interviewed at multiple timepoints to track changes in perception over time. | Evaluation unable to determine if partnership improved maternal and newborn health outcomes. Community perspectives not included. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 |

| Tynan [45] | 2018 | PNG | To examine healthcare worker perceptions of health system factors impacting on the performance of Prevention of Parent to Child (PPTCT) programmes. | Descriptive study | Qualitative – semi-structured interviews with healthcare workers involved in the program. | Sixteen interviews undertaken with healthcare workers involved in the PPTCT program. Major factors reported as barriers for implementing a successful PPTCT programme included broken equipment; problems with supply and access to HIV test kits, ART and HIV prophylaxis for children; significant shortage of appropriately trained and supported health care workers; and the absence of leadership and coordination of this complex, multi-staged national programme from central government. The need for women and children to engage with the health system over an extended period and often at different services with different health care workers was highlighted. Challenges were specifically faced in accomplishing initial diagnosis of the expectant mother and delivering postnatal and paediatric follow‐up services. A few participants also identified several weaknesses with health information systems including timely access to data and ineffective reporting for monitoring and evaluation. |

Sound methodological rigour. Classification of results according to the framework of the building blocks of a health system developed by WHO. | Patient perspectives limited. Inclusion of 2 provinces with high burden of HIV, may not reflect issues affecting provinces with lower burdens or different barriers to care. PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 |

| Usher [54] | 2003 | Fiji | To conduct an impact evaluation of the Nurse Practitioner role in Fiji. Nurse Practitioners must hold midwifery and public health qualifications, have approximately 15 years of service and have successfully completed a 14-month course run by the Fiji School of Nursing. | Descriptive study | Qualitative – semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions. | 18 nurse practitioners and 54 stakeholder interviews and three community focus group (22 community members) were conducted. Villagers who currently have access to the service provided by these NPs find the role to be extremely beneficial to the health of their community. They, and key stakeholders, expressed a high degree of satisfaction with the role. Issues raised related to the practice of using nurse practitioners to replace medical officer positions at hospitals, lack of formal career path and lack of involvement in decisions about placement in remote areas. |

Inclusion of community and all key stakeholder perspectives. Good rationale for and rigorous methodology. Clear description of Nurse Practitioner role. | Lack of qualitative data (interview or focus group quotes) to support findings. Implications of study may be overstated given lack of data provided. Ethics approval authority not specified. Fiji-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 4 |

| West [55] | 2017 | PNG | To determine how the PNG Maternal and Child Health Initiative approach contributed to strengthening midwifery education in PNG. | Program evaluation | Qualitative – semi-structured interviews. | 26 midwifery educators were interviewed. Individual and relationship factors perceived as enabling improved midwifery teaching and learning were knowing your own capabilities; being able to build relationships; and being motivated to improve the health status of women. Four themes identified as constraining midwifery educators were lacking a mutual understanding of capacity building; not feeling adequately prepared to work together; not feeling culturally competent and lack of a supportive environment. |

Criterion sampling used to ensure diversity of participant perspectives. Data collection and analysis underpinned by a theoretical framework. Strong use of quotes to support findings. | PNG-specific may not be generalisable to the Pacific region. | 5 |

| WHO [50] | 2005 | Regional (including PNG)) | WHO regional 'Making pregnancy safer' strategy. | Strategy review | - | Strategy contains 4 strategic areas with 12 component strategies. Pacific relevant ones selected below: Service capacity increased at the community and referral levels in all priority countries. Development of guidelines and services protocols around Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Birth attendants trained in Solomon Islands. Midwives trained in Vanuatu. Training curriculum on Pregnancy, childbirth, postnatal and newborn care (PCPNC) prepared for 10 Pacific island countries. |

|||

| Training on PCPNC conducted in 10 Pacific Is countries. Information systems strengthened to monitor the progress of achieving quality of care. Maternal child health surveillance system software has been developed and tested in Solomon Islands. Training conducted for 6 island countries. Pilot test of reproductive health surveillance system conducted in 2003 in Solomon Islands. Training on information systems conducted in Kiribati. Family planning promoted to reduce unwanted pregnancy: 10 Pacific Island countries have revised the service protocol of family planning to improve the quality of service. Seminars on STIs and HIV/AIDs conducted in Tuvalu. Partnerships strengthened for Making Pregnancy Safer programmes in the priority countries UNICEF, UNFPA, IPPF, PATH and the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) were actively involved in the development and finalisation of the Regional Framework for Accelerated Action for Sexual and Reproductive Health of Young People. |

Regional strategy, promoting partnerships and collaborations between agencies, scaling up known effective interventions. | One size fits all approach may not be appropriate for all countries in the region. | N/A | ||||||

| WHO [51] | 2009 | Regional | Meeting Report -Situation of Maternal and Newborn Health in the Pacific. | Strategy review | Meeting with key stakeholders to review current situation and progress made in Pacific Island countries and country inputs required for strategy document. | Country inputs to strategy documents to: reflect Pacific perspectives, strengthen newborn care in ‘Making Pregnancy Safer framework’, check data for accuracy and cite sources, review technical terms, improve access and availability of services, identify minimum competencies for skill birth attendants, ensure coherence and coordination among reproductive health and other health programs, identify role of men, gender based violence, improving emergency care, costing for countries to have evidence on how much maternal and newborn health interventions and programmes cost, improve monitoring and evaluation. | Regional strategy with emphasis on pacific solutions. | Costing of initiatives/framework and/or potential funding support not included. | N/A |

| WHO [52] | 2013 | Regional | Draft action plan for Healthy Newborns in the Western Pacific 2014-2018. | Draft action plan | Consultation meeting - held in Philippines. Plenary and small group discussions on the regional action plan. 5 small groups reviewed sections of the plan. Country teams reviewed implementation of Early Essential Newborn Care and identified key actions to move forward. | Ensure consistent adoption and implementation of EENC. Improve political and social support to ensure an enabling environment for EENC. Ensure availability, access, use of SBAs and essential MN commodities in a safe environment. Engage and mobilise families and communities to increase demand. Improve the availability and quality of perinatal information. |

Regional strategy, focus on implementation, use of group work. | Limited number of Pacific countries participated in consultation meeting. | N/A |

| WHO [75] | 2014 | Regional | Final Action Plan for Healthy Newborn Infants in WPRO (2014-2020). | Action plan | Consultation meeting - held in Philippines. Plenary and small group discussions on the regional action plan. 5 small groups reviewed sections of the plan. Country teams reviewed implementation of Early Essential Newborn Care and identified key actions to move forward. | Five strategic actions support full implementation of Early Essential Newborn Care (EENC): 1. Ensure consistent adoption and implementation of EENC. 2. Improve political and social support to ensure an enabling environment for EENC. 3. Ensure availability, access and use of SBAs and essential maternal and newborn commodities in a safe environment. 4. Engage and mobilise families and communities to increase demand. 5. Improve the quality and availability of perinatal information. |

Regional strategy, developed in collaboration, upstream/downstream initiatives included. | Only 2 Pacific countries included. | N/A |

| WHO [53] | 2016 | Regional (PNG, Solomon Islands) | First biennial progress report - Action Plan for Healthy Newborn Infants in the Western Pacific Region (2014-2020). To review progress of action plan for healthy newborn infants in Western Pacific Regional Area. | Progress report | Independent review group. | Report recommendations for next phase: 1. Plan and secure long-term funding. 2. Build consensus and create demand. 3. Further scale up coaching of the basic EENC package to 28,000 health facilities in the region. 4. Strengthen monitoring and evaluation for EENC. 5. Develop, test and introduce new methods and guidelines in collaboration with WHO and other partners. |

Coaching approach - emphasis on changing health worker practice, emphasis on quality of care during labour and childbirth. | Only 2 Pacific countries included. | N/A |

The Mixed Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT) assesses the quality of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. It focuses on methodological criteria. It is a 1–5 scale and includes five core quality criteria for each of the following five categories of study designs: (a) qualitative, (b) randomised controlled, (c) nonrandomised, (d) quantitative descriptive, and (e) mixed methods. N/A represents not assessable rather than not applicable.

3.1. Quality appraisal of included papers

Twenty-one of the 32 included papers (66%) were appraised for quality using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Table 1). Of these, 15 studies were of high quality, achieving the maximum score of five. Four studies were moderate quality and two studies were poor quality. The remaining reports, strategy or policy documents did not provide sufficient information to permit a complete MMAT appraisal to be done.

3.2. Overview of quality improvement interventions

A wide variety of QI interventions were identified. Several studies centred around community development and health promotion initiatives, such as promoting contraceptive use and immunisation [28], [29], [30]. Other interventions aimed to improve infrastructure, resources and equipment, such as: building staff houses and community health posts, renovations to existing health facilities, and increasing availability of various essential medical supplies, equipment and oxygen provision [31,32]. Several service-specific interventions aimed to improve morbidity and mortality audit systems [30,33–36], management of perinatal deaths and bereavement care [35,37], and antimicrobial prescribing practices [38].

There was an emphasis on education and training at the clinical service level, with many interventions focused on improving clinical skills in antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care for village health volunteers or traditional birth attendants, community health volunteers or workers and midwives [28–30,38–40]. Another example was training for Village Birth Attendants to conduct health promotion in addition to upskilling in referral processes [38,39]. There were several initiatives which aimed to strengthen tertiary education, such as, midwifery [41,42] and maternal and child health programs [43].

Other interventions included a contraceptive implant outreach service [44], prevention of parent to child HIV transmission programs [45], development of maternal and newborn health action plans [31], reviews of national clinical policies and standards [29], midwifery leadership programs [46] and the formation of Public Private Partnerships at regional and national levels [31,47].

3.3. Categorisation of interventions according to the four-level health system framework

Using the four level health system framework [27], most interventions operated at the care team level (frontline care providers) [30,39,40] or the organisation level (infrastructure and resources) [29,31,32,48]. Some focused on the wider health system environment including strengthening relationships between community-based services and broader health promotion [28,49], development of action, strategy and annual activity plans [29,50–53] and strengthening the education sector [41,54–56]. A leadership program for nursing and midwifery leaders [46] was considered to operate at both the care team and organisation level. Regional strategies and action plans generally encompassed a whole of health system approach [50,51].

Only one intervention was identified that targeted the patient level. This was an incentive program to encourage mothers to give birth in health facilities by providing a mother-baby support gift [48,33]. This program also acted at the care team level, with staff incentives and upskilling in emergency obstetric and newborn care.

3.4. Categorisation of interventions according to WHO quality maternal and newborn care standards

Interventions were categorised according to the eight domains of the WHO Standards for Improving Quality of Maternal and Newborn Care in Health Facilities (Table 2). Most interventions focused on domain 1, the provision of evidence-based routine care and management of complications, and domain 7, the availability of competent and motivated staff. Several interventions also addressed domain 8, which focuses on the physical environment of the health facility including water, sanitation, electricity, medicines and equipment required for maternal and newborn care. Some interventions covered health information systems and referral processes (domains 2 and 3, respectively). Very few interventions addressed domains 4, 5 and 6, which all relate to the experience of care and include communication with women and their families, promotion of respectful and dignified care and the provision of emotional support.

Table 2.

Alignment of quality improvement interventions with WHO Standards for Improving Quality of Maternal and Newborn Care in Health Facilities.a

| WHO standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision of care domains |

Experience of care domains |

Both experience and provision of care domains |

||||||||

| Author(s) | Year | Intervention described | 1. Routine, evidence-based care and management of complications during labour, childbirth and the early postnatal period, according to WHO guidelines | 2. The health information system enables use of data to ensure early, appropriate action to improve the care of every woman and newborn | 3. Every woman and newborn with condition(s) that cannot be dealt with effectively with the available resources is appropriately referred | 4. Communication with women and their families is effective and responds to their needs and preferences | 5. Women and newborns receive care with respect and preservation of their dignity | 6. Every woman and her family are provided with emotional support that is sensitive to their needs and strengthens the woman's capability | 7. For every woman and newborn, competent, motivated staff are consistently available to provide routine care and manage complications | 8. The health facility has an appropriate physical environment, with adequate water, sanitation and energy supplies, medicines, supplies and equipment for routine maternal and newborn care and management of complications |

| Ashwell and Barclay | 2009a | Broad description of intervention: improved access to health services, in-service training for staff, community development, health promotion interventions, sanitation, hygiene, housing, behaviour and attitude changes regard health and survival of women and children. | ● | |||||||

| Ashwell and Barclay | 2009b | In-service training for district health workers, improvements to cold chain vaccine supply system, behaviour and attitude changes in relation to sanitation hygiene and housing, strengthening and expansion of existing health volunteer programs. | ● | |||||||

| Bettiol | 2004 | Village Birth Attendant training program – 3 week course in basic midwifery skills and attendance in antenatal clinic. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Choy and Duke | 2000 | Women from remote villages trained to become Village Child Health Workers – one-month course included 10 basic lessons for child health, when to refer. Integrated into postgraduate nursing degree - child nursing students were the teachers. | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Datta et al. | 2013 | Development of natonal action plan for elimination of maternal and neonatal tetnaus in PNG (immunisation program, training of midwives, community health workers, improved antenatal care. | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Dawson | 2016 | Integration of Clinical Midwifery Facilitators into four training schools to mentor PNG midwifery educators. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Duke | 2017 | Implementation of oxygen delivery systems for paediatric use in PNG. | ● | ● | ||||||

| Field | 2018a | Public private partnership for improving rural health service delivery (including development of annual activity plan, building staff houses, provision of boats to health facilities, health facility rennovations, workforce training, supplementary medical supplies, village health volunteer program, outreach clinics including antenatal care and family planning services). | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Field | 2018b | Development of national policies and standards, establishment of partnerships at provincial level with state and non-state partners in health, health worker training, infrastructure development, community level health promotion activities). | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Gardiner | 2016 | Program to improve maternity care providers knowledge and confidence in managing perinatal deaths. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Gupta | 2017 | Contraceptive implant outrach program. | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Kamblijambi | 2017 | Evaluation of a bachelor of clinical maternal and child health with a double major in midwifery and child health. | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Kirby | 2013 | Mother Baby Gift program, staff incentives, emergency obstetric staff training, emergency obstetric kits, water and solar lighting installation, construction of waiting houses for expectant mothers, emergency food fund for mothers. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Kirby | 2015 | Offering women ‘mother baby gifts’ at the time of birth as incentives to birth in a facility. | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Mannering | 2013 | Education package to reduce infant mortality rate and improve ealth of neonates. | ● | ● | ||||||

| Moores | 2016 | Midwifery education initiative to improve standard of clinical teaching and practice in PNG – curriculum review, provision of teaching and clinical simulation resources, appointment of clinical midwifery facilitators. | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Narayan | 2009 | Improved infection control practices in a neonatal intensive care unit. | ● | ● | ||||||

| O'Keefe | 2011 | Village Health Volunteer Program – training in antenatal care, birth attendants. | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Olita'a | 2019 | A protocol for minimal or no antibiotics in term babies born after premature rupture of membranes (PROM). | ● | |||||||

| Raman | 2015 | Revision and trial of a pre-existing perinatal mortality audit datasheet. | ● | ● | ||||||

| Rumsey | 2016 | Mentorship program for upcoming nursing and midwifery leaders. | ● | |||||||

| Sa'avu | 2014 | Improvements to neonatal care including staff training, oxygen and pulse oximeter installation. | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Sandakabatu | 2018 | Revised neonatal and child death audit process. | ● | ● | ||||||

| Thiessen | 2018 | Private public partnership involving the establishment of a reproductive training unit to conduct training for reproductive health workers in essential and emergency obstetric care. | ● | ● | ||||||

| Tynan | 2018 | Prevention of parent to child HIV program including antenatal care; HIV counselling and testing; provision of ART; supervised birth; infant prophylaxis; education on infant feeding practices; infant follow‐up including HIV testing; family planning; linkages to long‐term HIV care; and treatment. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Usher | 2003 | Establishment of nurse practitioner program. | ● | ● | ||||||

| West | 2017 | Clinical mentoring, supervision and teaching program for midwifery educators. | ● | ● | ||||||

| WHO | 2005 | WHO regional strategy – making pregnancy safer. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| WHO | 2009 | WHO meeting report – situation of maternal and newborn health in the Pacific. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| WHO | 2013 | WHO draft action plan for healthy newborns in Western Pacific. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| WHO | 2014 | WHO final action plan for healthy newborn infants in Western Pacific. | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| WHO | 2016 | WHO first biennial progress report – action plan for healthy newborn infants in Western Pacific. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

Alignment was determined by examining which domains initiatives addressed.

3.5. Enablers and barriers to quality improvement interventions

Several enablers and barriers to effective QI maternal and newborn health interventions were identified across the four health system levels. At the environment level, enablers included strong relationships with decision making bodies and interventions which aligned with national policies and priorities [47]. Interventions that had little to no involvement with national health departments were less likely to influence national policies and programs [28,47]. Restrictive donor-defined objectives, contractual obligations [28], and funding delays [31] were also described as limiting intervention effectiveness. For example, a community-based health project in PNG identified the lack of engagement with lower-level stakeholders as a barrier to overall success [28].

Several interventions noted the importance of solid community engagement and leadership. This included good communication and working relationships with the community [54] and involvement of key community figures who could act as catalysts for change [32,49]. For example, a women and child health project implemented across 93 communities in PNG found that the most successful project communities were the ones with motivated leaders with vision, commitment and community respect [49]. Conversely, “top down” approaches that failed to engage meaningfully with district or provincial level health administrators, community health organisations or healthcare workers were less likely to be effective [49]. Lack of governance was found to result in confused decision making, unclear roles and responsibilities, and ownership struggles [47].

QI interventions were rarely led by governments alone; most were a collaborative effort between NGOs, aid organisations, local health facilities, state/provincial departments or national governments. At the organisation level, one PNG study which aimed to assess the quality and coverage of rural health services found higher performance among health services operated by churches or private companies [29]. A collaborative partnership approach with government and non-government actors was frequently identified as critical to the success of programs. In addition to strong governance structures [49], leadership, teamwork, clear communication, standardised processes [35,36], and strong information systems were also found to be important [45]. Several studies noted the importance of strong coordination at multiple levels of the health system [29,32,47,49]. A few studies described public-private partnerships [31,47], which were considered to be most successful when they were collaborative, involved multi-pronged activities and targeted several levels of the health system [29,31]. The Community Mine Continuation Agreement Middle (CMCA) and South Fly Health Program (the Health Program) [31] is an example of a Public Private Partnership which improved maternal and newborn health service delivery in remote PNG; particularly through an emphasis on partnerships, collaboration and support for the fundamental enablers of primary health care at the community level. This included improved health facility infrastructure, equipment, medical supplies, transport availability and health worker training.

Hospital capacity limitations (for example adults and newborns managed in general wards together) [57], infrastructure and utilities issues [32,54,57], and poor infection control measures [34,57] were each barriers to implementation of effective QI interventions. It was notable that some QI activities were introduced in facilities that were not equipped with sufficient supplies [31,35,45] (such as basic equipment for care of sick neonates absent or faulty) [57]. Ensuring adequate equipment, resources and utilities [31,36], and using simple measures and protocols (such as hand hygiene, single-use vials of IV fluid bags and strict aseptic techniques) [34] were necessary to create a supportive environment for a QI intervention. Many organisations were found to provide inadequate education and training opportunities for staff which was compounded by insufficient resources, programs that were too short to meet their objectives, limited opportunities for staff to implement knowledge and skills gained in their work environment [42,43], and a lack of career pathways [54]. Programs which targeted health care leaders were strengthened by the inclusion of leadership training and local mentors – interviews with thirty four nurses and midwives across 12 Pacific countries highlighted this finding [46].

Successful interventions at the care team level included several education and training programs. Key enabling elements included motivated participants [55], rural placements [43], and relationship building and networking opportunities [55]. Well-adapted learning tools [49], practical skills-based learning approaches [37] and group learning [43] were examples of effective teaching and training tools. The inclusion of leadership skills in addition to theoretical and clinical knowledge [42] was noted to be important. Ineffective interventions at the care team level was related to inadequate and poorly skilled staff [35,45] and poor adherence to protocols [34]. The single intervention at the patient level (mother-baby gift project) demonstrated the importance of incorporating sociocultural values in addition to incentives to encourage birthing in healthcare facilities [48].

4. Discussion

This is the first comprehensive review of interventions undertaken in Pacific LMICs to improve the quality of maternal and newborn care. Thirty-two papers were identified, most of which described interventions specific to health care teams and health services rather than the patient or the wider health system. Many interventions involved education and training of healthcare volunteers and workers, and projects to improve maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality review processes. There was a lack of interventions that aimed to improve the healthcare experience for women and newborns.

Over half of all papers described interventions in PNG. PNG is the largest and most populated country in the Pacific [58] and has some of the highest maternal and neonatal mortality indicators in the region [59] which may result in focused efforts in this country. PNG is likely to also have the greatest research capacity in the Pacific with a dedicated national medical research institute [60].

Mixed methods approaches were used by the majority of papers, which is in keeping with recommendations for health systems research [61]. The impact of health system interventions on health outcomes are difficult to assess and evaluate through quantitative measures alone and a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods provides a stronger and richer assessment of the effectiveness of quality of care interventions [61,62]. There was a paucity of well-controlled studies with capacity to demonstrate impact at scale, which is consistent with another review of maternal and newborn interviews in LMICs [63]. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [25] proved helpful in assessing credibility of the papers evaluated, the majority scoring five out of five points, reflecting the high quality of most of the studies included. However, several studies rated poorly. Studies were not excluded based on their quality score as the aim of a scoping review is to map and describe the evidence, however their methodological limitations highlight the need for better application of rigorous health service research methods.

Very few papers that presented intervention evaluations explored patient and community perspectives or patient-centred outcomes. Patient and community views are essential to shaping effective maternal and child health interventions. Community buy in with local leadership is paramount for sustainability and it is important to have community involvement in the governance of maternal and child health programs [28,63]. The predominance of interventions targeting the care team and health service is consistent with a previous review of maternal and newborn health initiatives in non-Pacific countries, which also identified an emphasis on health workforce interventions and service delivery [63]. The high number of education and training interventions for healthcare workers and volunteers highlights the centrality of healthcare workers in health system QI. Indeed, without a health workforce there is no health system. However, the workforce needs to be enabled, equipped and supported to deliver quality care; and effective coverage requires services to be accessible, acceptable and of high quality [14]. In the Pacific and indeed across many LMICs, health care workers receive insufficient training and professional development opportunities to keep their skills and practice up to date [64]. Temporary clinical skill development programs for discrete groups of healthcare workers provides limited benefits to a healthcare service. More important is ensuring the workplace and its health system values and commits to a sustainable education program [65]. Further, improving healthcare worker education at universities and training colleges can have widespread benefits, particularly where leadership and management skills are included in addition to clinical skills training [66]. Effective mentorship (particularly from local mentors), role modelling and networking opportunities are important in developing health leaders, as was noted in several studies [46,54].