Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to screen for a one year Brazilian elderly women who were physically active before of COVID-19 pandemic-induced lockdown and to assess the consequences of physical inactivity on body weight and muscle function loss.

Measurements

A cohort study of one-year was conducted with twenty-nine physically active elderly (65.5±5.6y) women. Pre-assessment was took in December 2019 and post (a year later) was performed in January 2021, during the lockdown induced by COVID-19 pandemic. Body mass (kg) was obtained using the digital scale. Handgrip strength (HGS) of the non-dominant hand was determined using an electronic dynamometer. Muscle function loss was assessed using the SARC-F questionnaire.

Results

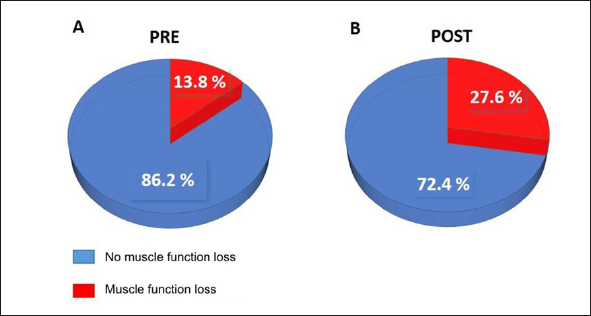

After one year, body weight (p=0.002) and BMI (p=0.001) increased significantly, with an average percentage of change in body mass of +3.0±5.2%. Consequently, there was a change in classification of BMI pre- and post-one year (malnutrition: 17.2% to 17.2%, normal weight: 41.4% to 37.9%, and overweight: 41.4% to 44.9%). Additionally, was found increased muscle function loss (SARC-F≥4) of 13.8% to 27.6% of elderly women.

Conclusion

In Brazilian physically active elderly women, we found that the physical inactivity imposed by during the lockdown increased the body mass and muscle function loss.

Key words: Muscle function loss, SARC-F, elderly, COVID-19, lockdown

Introduction

Sarcopenia aging is associated with decreased muscle function, mass and strength, which increase the risk of sarcopenia, resulting in worse of quality of life (1). Sarcopenia can be exacerbated by decreased physical activity. Thus, resistance training has been stimulated, to improve clinical and functional capacity and reduce mortality from inactivity in elderly populations (2). However, after confirmation in March 2020 by the World Health Organization on pandemic triggered by the Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, (COVID-19), social isolation measures were adopted and physical activities carried out in collective environments were prohibited (3).

Likewise, physical inactivity has been identified as a strong modifiable risk factor for COVID-19, since inactive patients had a greater chance of hospitalization when compared to those engaged in physical activity program (4). In addition, COVID-19 has more severe clinical consequences in the elderly. So, when hospitalization is necessary, there is a greater risk of developing sarcopenia (5). Thus, thinking about the sedentary behaviour for elderly people during the lockdown in COVID-19 pandemic, we hypothesised that elderly had increased risk for sarcopenia muscle function loss and gain of body weight. Thus, this study aimed to screen for a one year Brazilian elderly women who were physically active before of COVID-19 pandemic-induced lockdown and to assess the consequences of physical inactivity on body weight and muscle function loss.

Methods

A cohort study of one-year was conducted with twenty-nine physically active elderly women in Goiânia, Brazil. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee (under the number 3.712.465). Pre-assessment was took in December 2019 and post (a year later) was performed in January 2021, during the lockdown induced by COVID-19 pandemic.

Body mass (kg) was obtained using the digital scale (Toledo®, Brazil) and the height measured with a portable stadiometer (Sanny®, Brazil) for later calculation of the body mass index (BMI). Handgrip strength (HGS) of the non-dominant hand was determined using an electronic dynamometer (Camry, EH101, China) and the highest value obtained between three attempts was recorded. Blood pressure was measured with the OMRON-HEM 705 CP semiautomatic device and classified according to the Brazilian Guideline for Hypertension (6). SARC-F questionnaire was applied to asses the muscle function loss (if SARC-F ≥4) (7). Continuous variables were described as mean and standard deviation and categorical as a percentage. The paired t test was applied to assess differences pre- and post-one year of lockdown. The Medcalc®, Belgium software was used for the analyzes and p <0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

The mean age and body weight of the participants at the beginning of the study were 65.5±5.6y and 63.1±2.6kg (Table 1). The mean HGS was 21.2±4.9 kg (17.2% with low muscle strength) and 48.3% were normotensive (≤120×80 mmHg), 41.4% prehypertensive (≥121×81 and ≤139×89 mmHg), and 10.3% with hypertension (≥140×90 mmHg).

Table 1.

Impact of the pandemic COVID-19 on anthropometry and muscle function loss in elderly women

| Variables | Pre (ME ± SD) | Post (ME ± SD) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) | 63.1 ± 12.6 | 65.0 ± 13.4 | 0.002* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.3 ± 4.9 | 27.2 ± 5.1 | 0.001* |

| SARC-F | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 2.0 ± 1.7 | 0.0004* |

ME: mean; SD: standard deviation; *p<0.05 was considered as significant.

After one year, body weight (p=0.002) and BMI (p=0.001) increased significantly (Table 1), with an average percentage of change in body mass of +3.0±5.2%. Consequently, there was a change in classification of BMI pre- and post-one year (malnutrition: 17.2% to 17.2%, normal weight: 41.4% to 37.9%, and overweight: 41.4% to 44.9%). Additionally, was found increased muscle function loss (SARC-F≥4) of 13.8% to 27.6% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of muscle function loss in elderly women before the pandemic and one year after

Discussion

This study found that after one year of lockdown due to the pandemic COVID-19, physically active elderly women increased body mass and the Muscle function loss. How overweight and Muscle function loss aggravates the hospitalization for COVID-19 (5), the adoption of preventive strategies against sarcopenia, such as an adequate dietary protein consumption and resistance training are even more important (1). Previous studies strengthens the need for additional motivation for individuals to remain active, even with quarantine, with activities kept within their own home (4,8).

The increase in body mass observed in our study was possibly due to consequence in reduction of energy expenditure induced by the lockdown. In agreement with our data, Visser, Shaap and Wijnhoven (8) in a longitudinal study performed in Netherland, also found body mass gain during quarantine, with a greater impact in elderly people. In addition, they found an association between physical inactivity and a increased risk of overfeeding and alcohol consumption. Di Renzo et al., (9) in Italian subjects, justified that the perception of body mass gain may be due to increased feeling of hunger and the consequent change in eating habits verified during the lockdown period. These results highlights the demand to maintain a healthy lifestyle in order to prevent the adiposity, which is an aggravating factor in respiratory failure in patients with COVID-19 (9).

As limitations, our study had a small sample size, and did not assess the food intake, and lifestyle habits. On the other hand, it was the first study to measure the impact of lockdown on the screening of muscle function loss in Brazilian elderly women during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, providing important insights to maintain physical activity during the pandemic. In conclusion, we found that the physical inactivity imposed during the lockdown increased the body mass and the muscle function loss in physically active elderly women. Thus, we highlights the importance to use the SARC-F questionnaire during the COVID-19 pandemic to screening the muscle function loss.

Ethical standards: All authors declare: 1. That this manuscript is not published elsewhere; 2. Any conflicts of interest; 3. They meet criteria for authorship and ensure appropriate acknowledgments made in the manuscript; 4. Appropriate funding statements in the manuscript; 5. They will inform the journal if any subsequent errors are found in the manuscript.

Conflict of interests: All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age and Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cadore E. Strength and Endurance Training Prescription in Healthy and Frail Elderly. Aging Dis. 2014;5(3):183–195. doi: 10.14336/AD.2014.0500183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, et al. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. The Lancet. Lancet Publishing Group. 2021;395(10223):470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sallis R, Young DR, Tartof SY, et al. Physical inactivity is associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes: a study in 48 440 adult patients. Br J Sports Med. 2021;0:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-104080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wierdsma NJ, Kruizenga HM, Konings LA, et al. Poor nutritional status, risk of sarcopenia and nutrition related complaints are prevalent in COVID-19 patients during and after hospital admission. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021;0(0):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malachias MVB, Gomes MAM, Nobre F, et al. 7th Brazilian Guideline of Arterial Hypertension: Chapter 2 — Diagnosis and classification. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016;107(3):7–13. doi: 10.5935/abc.20160152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. SARC-F: A simple questionnaire to rapidly diagnose sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):531–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visser M, Schaap LA, Wijnhoven HAH. Self-reported impact of the covid-19 pandemic on nutrition and physical activity behaviour in dutch older adults living independently. Nutrients. 2020;12(12):1–11. doi: 10.3390/nu12123708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Pivari F, et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):229. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]