Abstract

Introduction

Beginning in 1999, residents in emergency medicine have been expected to demonstrate competence in the six Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Core Competencies. Expectations were further refined and clarified through the introduction of the Milestones in 2013. Emerging research and data from milestone reporting has illustrated the need for modification of the original milestones. Against this backdrop, the ACGME convened a committee to review and revise the original milestones.

Methods

The working group was convened in December 2018 and consisted of representatives from the American Board of Emergency Medicine, American Osteopathic Association, Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine, Association of American Medical Colleges, ACGME‐Emergency Medicine Review Committee, three community members, a resident member, and a public member. This group also included members from both academic and community emergency medicine programs. The group was overseen by the ACGME vice president for milestones development and met in person one time followed by four virtual sessions to revise and draft the Emergency Medicine Milestones and Supplemental Guide as part of the ACGME Milestones 2.0 Project.

Results

Using data from milestones reporting, needs assessment data, stakeholder interviews, and community commentary, the working group engaged in revisions and updates for the Emergency Medicine Milestones and created a supplemental guide to aid programs in the design of programmatic assessment for the milestones.

Conclusion

The Emergency Medicine Milestones 2.0 provide updated specialty‐specific, competency‐based behavioral anchors to guide the assessment of residents, the design of curricula, and the advancement of emergency medicine training programs.

INTRODUCTION

The transition to competency‐based medical education (CBME) in the United States began in 1999 with the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education's (ACGME) introduction of the six core competencies: medical knowledge (MK), patient care (PC), interpersonal and communication skills (ICS), professionalism (PROF), systems‐based practice (SBP), and practice‐based learning and improvement (PBLI). 1 While the identification of the core competencies represented the first step in the transition, in 2013 the Next Accreditation System launched and brought outcomes‐based reporting to the forefront of resident performance evaluation and signaled a transition from a process focus to an outcomes focus. 2 Emergency medicine (EM) was one of the first seven specialties to engage in this transition. 3

Milestones represent discrete accomplishments or behaviors that a physician in training demonstrates as part of the process to become an independent, competent physician. They expand upon the original core competencies by providing detailed behavioral anchors within the competency; identifying specialty‐specific knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs; and providing a progressive framework to achieve the stated competency. 2 The choice of a five‐stage model is consistent with the Dreyfus framework of expertise development, beginning with novice, followed by advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert. 4

Implementation of milestones assessment marked a tremendous step in the uniform evaluation of individual resident progress, regardless of residency. The original EM milestones represented 23 subcompetencies of the six core competencies, with individual milestone statements within each subcompetency. Milestones created a uniform language for which assessment and remediation became more consistent across the specialty.

As the use of the Milestones 1.0 evolved, and assessment instruments developed, it became clear that the milestones would benefit from a reassessment of the subcompetencies as well as the gradations of competency achievement within each subcompetency. The Milestones 2.0 Working Group was assembled for this purpose.

EMERGING CHALLENGES FROM MILESTONES 1.0

Despite the intent to build a common language around physician training and assessment, the acceptance and implementation of the core competencies were hindered by a lack of familiarity with the meaning of these competencies within the context of specialty‐specific training. 5

While milestones were written using behavioral anchors, the assessment of milestones introduced new challenges. At times, assessment was limited by a lack of developmental progression across subcompetency levels. Orphan milestones, or those milestones with no link to prior or following levels, introduced random performance metrics without longitudinal progression. Many milestones also included descriptive adjectives that increased confusion when assessing performance.

The ACGME allowed for program‐level flexibility in the implementation and assessment of the milestones. Unfortunately, milestones were used in unintended ways. At times milestones assessments were substituted in place of prior assessment tools, including global ratings. 6 Using milestones as the basis for end‐of‐shift evaluations led to inflation of scoring. 7 Other challenges emerged as research highlighted the variability in assessment methods when compared to residents' assessed abilities. 8 Another area of concern was related to milestones and level of training. The potential for assigning a resident a straight‐line score for their given year would undermine the validity of the milestones. Fortunately, while some programs fell victim to straight‐line scoring, most avoided this potential assessment error. 9

The transition from medical school to residency presented yet another area of challenge. While the milestones set clear, specialty‐specific expectations, medical students entering residency are expected to meet the Level 1 milestones. Given the structure of undergraduate medical education, there is a gap in teaching and assessing students entering EM related to their ability to achieve the Level 1 subcompetencies. 10

THE PROCESS FOR UPDATING THE MILESTONE

Between the years 2013 and 2014, specialty‐specific milestones were independently developed resulting in inconsistencies in content as well as wide variability among and between medical specialties. This was supported by subsequent milestone research. One study revealed that among the 26 core specialties and the transitional year, PROF was described in 230 different ways, 171 for PBL, 176 for ICS, and 122 for SBP. 11 These differences were raised by focus groups of key stakeholders that included residents, program directors, faculty, designated institutional officials, specialty society meetings, and institution visits. 11 This feedback illustrated how the variability in the interpretation of the subcompetencies created a challenge to sharing assessment tools and collaboration for comprehensive faculty development across the specialties. Realizing that there were unintended consequences of the initial development and implementation of the milestones, the ACGME Department of Research, Milestone Development, and Evaluation developed a process for revisions.

In Fall 2018, the ACGME appointed a working group composed of members representing key EM organizations including the American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM), American Osteopathic Association (AOA), American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC), Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine (CORD), ACGME Recognition and Review Committee (RRC‐EM), and the Emergency Medicine Residents Association (EMRA). In addition, there were three physician community members, one public member, and ACGME executive and support staff. This diverse representation included academic and community sites from urban, suburban, and rural programs. The group convened in person from September 16–17, 2019, to begin the process of milestone review and vision. Additional meetings were scheduled for Spring 2020. Unfortunately, the global SARS‐CoV‐2 (COVID‐19) pandemic delayed further work until a transition to virtual work was complete and the group continued the revisions over multiple video conferences.

Over the course of 1 year, the working group broke down each subcompetency and milestone, reviewed its intent and applicability to current EM training, and revised as necessary. This process started with a brainstorming session where the working group, representing diverse backgrounds from across the country, took time to predict what changes and challenges EM and residency training would face with in the 5 years, and how we could best shape the milestones to support current and future residents.

NEW THINKING ABOUT PC AND MK

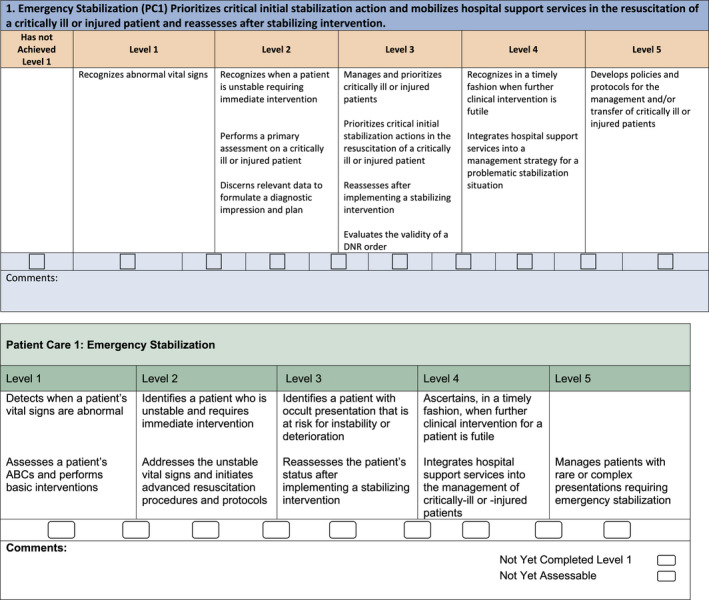

The PC subcompetencies underwent significant revision. Given the progressive nature of competence, all milestones needed to have a link to previous and subsequent milestones. Milestones also needed to progress through at least four levels to be considered and no more than three developmental trajectories were considered for any level. Whenever possible, opaque descriptive adjectives were eliminated in favor of definitive language (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of Milestones 1.0 and 2.0 for patient care—emergency stabilization. In Version 1.0 (top), the levels contained multiple concepts and orphan milestones emerged unrelated to prior levels. In Version 2.0 (bottom), progression across the levels is simplified and relates directly to the prior and following levels

Perhaps the biggest change was the elimination of specific procedural subcompetencies (see Table 1). Version 1.0 contained six subcompetencies related to procedural performance: general approach to procedures (PC9), airway management (PC10), anesthesia and pain management (PC11), goal‐directed ultrasound (PC12), wound management (PC13), and vascular access (PC14). While the milestones within these subcompetencies contained numerous assessable behaviors, they also had many orphan milestones and measurable outcomes did not always correspond with the acquisition of competence. Furthermore, the working group found that focusing on five procedures neglects the fact that EM physicians must obtain competence in a multitude of other procedures. Thus, the decision was made to broaden the scope of the procedural competency on milestones that apply to all potential procedures: anatomy and physiology, indications, risks, benefits, kinesthetic performance, and the management of complications. Programs gain significant autonomy in defining basic versus advanced procedures for their given context. The concept of graduated supervision has been increasingly recognized in procedural assessment and thus was incorporated into the language of this subcompetency. 12

TABLE 1.

Comparison of subcompetencies in Milestones 1.0 and 2.0

| Milestones 1.0 | Milestones 2.0 |

|---|---|

|

PC1: Emergency Stabilization PC2: Performance of Focused History and Physical Exam PC3: Diagnostic Studies PC4: Diagnosis PC5: Pharmacotherapy PC6: Observation and Reassessment PC7: Disposition PC8: Multi‐tasking (Task‐switching) |

PC1: Emergency Stabilization PC2: Performance of a Focused History and Physical Exam PC3: Diagnostic Studies PC4: Diagnosis PC5: Pharmacotherapy PC6: Reassessment and Disposition PC7: Multitasking (Task‐Switching) |

|

PC9: General Approach to Procedures PC10: Airway Management PC11: Anesthesia and Acute Pain Management PC12: Other Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures: Goal‐directed Focused Ultrasound (Diagnostic/Procedural) PC13: Other Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures: Wound Management PC14: Other Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures: Vascular Access |

PC8: General Approach to Procedures |

| MK: Medical Knowledge |

MK1: Scientific Knowledge MK2: Treatment and Clinical Reasoning |

|

SBP1: Patient Safety SBP2: Systems‐based Management SBP3: Technology |

SBP1: Patient Safety SBP2: Quality Improvement SBP3: System Navigation for Patient‐Centered Care SBP4: Physician Role in Health Care Systems |

| PBLI: Practice‐based Performance Improvement |

PBLI1: Evidence‐Based and Informed Practice PBLI2: Reflective Practice and Commitment to Personal Growth |

|

PROF1: Professional values PROF2: Accountability |

PROF1: Professional Behavior and Ethical Principles PROF2: Accountability/Conscientiousness PROF3: Self‐awareness and Well‐being |

|

ICS1: Patient centered communication ICS2: Team Management |

ICS1: Patient‐ and Family‐centered Communication ICS2: Interprofessional and Team Communication ICS3: Communication within Health Care Systems |

MK was another competency that underwent significant revisions. In version 1.0, this subcompetency predominately focused on a resident's ability to pass examinations and rotation evaluations. As with the procedural milestones, MK 2.0 attempts to expand our thinking and to consider how we will assess scientific knowledge and decision‐making.

THE HARMONIZED MILESTONES

It was recognized that while MK and PC must be tailored to each specialty, there was an opportunity to create a standardized approach to the milestones in the other four competencies, because they have shared goals across all specialties. These came to be known as the harmonized milestones. To create the harmonized milestones, the ACGME formed four working groups composed of representatives from all specialties, including program directors, content experts, and interprofessional team members. These working groups created two to three subcompetencies for PROF, ICS, PBLI, and SBP that were germane to all specialties and subspecialties. Feedback and suggestions for these subcompetencies were given by the Milestones 2.0 Summit participants in 2016 and subsequent editing by working groups ensued. Further revisions were made following a public review and comment period in 2017. 11 The harmonized milestones were further modified to tailor the sub‐competencies for each specialty by the specialty‐specific Milestones 2.0 workgroups. Key stakeholder EM organizations designated representatives to participate in the EM Milestones 2.0 workgroup.

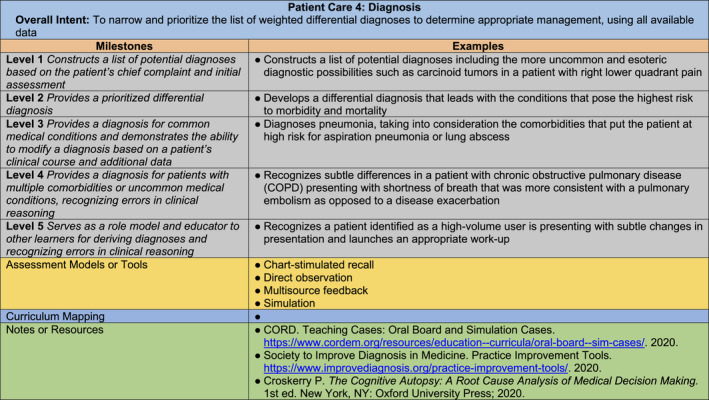

SUPPLEMENTAL GUIDE

The supplemental guide was created as a tool for residency program leadership and clinical competency committees (CCCs) to use in conjunction with the milestones. The supplemental guide includes the intent, examples, resources, and assessment models and tools for each subcompetency (Figure 2). The inclusion of these elements in the supplemental guide allowed the milestone subcompetencies to be streamlined.

FIGURE 2.

Example from The Emergency Medicine Supplemental Guide for Patient Care 4

After the EM Milestones 2.0 workgroup modified the PC and MK milestones and adapted the harmonized milestones to fit our specialty, they crafted the content for the supplemental guide. The goal of the examples was to assist residency leadership in interpreting the subcompetencies and provide a framework in which they may be applied. These examples were tailored to include clinical or “real‐world” scenarios germane to EM. Resources and evaluation tools were included to support the intent of the subcompetencies and provide qualitative measures that residency programs may use for qualitative assessment.

The workgroup created a second draft after the examples were reviewed and edited during two additional meetings. This draft was submitted for public comment and further modified prior to the final product in Fall 2020.

Residency programs and CCC members will need to review the new milestones and determine if the current assessment tools and modalities are appropriate for use or require modification moving forward. Once the means of assessment are determined, programs are encouraged to create their own shared mental model pertaining to the new milestones. This may be done by having the CCC review the subcompetencies and determine expectations for each level based on the training processes that are specific to their programs. Because patient populations, resources, and faculty vary from program to program, having a shared mental model will facilitate discussion of a resident's progression throughout their training. An editable version of the supplemental guide is available to serve as a jumping‐off point for this process to assist with this exercise.

GOING FORWARD

EM continues to grow as a specialty. As medical education evolves to focus on the linkage between preventative, chronic, and acute care, EM sits at a unique intersection between all specialties. 13 The language within the milestones reflects the specialty's ability to bridge this linkage while providing a logical approach to the development of competent physicians.

Milestones 2.0 represents the gradual evolution in our thinking about competence in EM physicians. When the working group first convened, we were challenged to consider the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed for graduates in 2025. Many of these considerations found their way into the revised milestones. Now that the milestones and supplemental guide have been published, the challenging work begins. Assessment of residents remains a perennial struggle in medical education. We have attempted to provide a framework for the creation of a shared mental model with the publication of the supplemental guide. Standardizing the language of SBP, PBLI, PROF, and ICS offers the possibility of interspecialty collaboration to develop new tools and collaborate on the continuous assessment of residents.

The ACGME has committed to a continual review and revision of the milestones to ensure their relevance. The process was quite different for this second version, which leaves us to imagine what might come next. Will the milestones lead to a review of the six core competencies? Will milestones be the tool that moves graduate medical education to a fully competency‐based system? Likely not, but perhaps they can be the inspiration for confronting a big, hairy, audacious goal in EM residency training, the move to make training fully competency‐based within the decade.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

LE is employed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the review and revision of the milestones over the course of multiple meetings and work periods in between. The authors are listed in the order of their contribution to the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Sydney Mclean and Braden Harsy for their continual support of the workgroup. The authors also thank their colleagues on the Milestone 2.0 workgroup who willingly gave their support and expertise to this project.

Cooney RR, Murano T, Ring H, Starr R, Beeson MS, Edgar L. The Emergency Medicine Milestones 2.0: Setting the stage for 2025 and beyond. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5:e10640. 10.1002/aet2.10640

Supervising Editor: Susan E. Farrell, MD.

Funding information

The ACGME provided financial support including travel expenses and meeting space to all members of the workgroup.

REFERENCES

- 1. Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project: retrospective and prospective. Med Teach. 2007;29(7):648‐654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beeson MS, Carter WA, Christopher TA, et al. The development of the emergency medicine milestones. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(7):724‐729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Swing SR, Beeson MS, Carraccio C, et al. Educational milestone development in the first 7 specialties to enter the next accreditation system. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):98‐106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Batalden P, Leach D, Swing S, Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education. Health Aff. 2002;21(5):103‐111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Edgar L, Roberts S, Holmboe E. Milestones 2.0: a step forward. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(3):367‐369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carter WA. Milestone myths and misperceptions. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1):18‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dehon E, Jones J, Puskarich M, Sandifer JP, Sikes K. Use of emergency medicine milestones as items on end‐of‐shift evaluations results in overestimates of residents' proficiency level. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(2):192‐196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hauff SR, Hopson LR, Losman E, et al. Programmatic assessment of level 1 milestones in incoming interns. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(6):694‐698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beeson MS, Hamstra SJ, Barton MA, et al. Straight line scoring by clinical competency committees using emergency medicine milestones. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(6):716‐720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Santen SA, Rademacher N, Heron SL, Khandelwal S, Hauff S, Hopson L. How competent are emergency medicine interns for level 1 milestones: who is responsible? Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(7):736‐739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Edgar L, Roberts S, Yaghmour NA, et al. Competency crosswalk: a multispecialty review of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Milestones across four competency domains. Acad Med. 2018;93(7):1035‐1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gofton WT, Dudek NL, Wood TJ, Balaa F, Hamstra SJ. The Ottawa Surgical Competency Operating Room Evaluation (O‐SCORE): a tool to assess surgical competence. Acad Med. 2012;87(10):1401‐1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sklar DP, Handel DA, Hoekstra J, Baren JM, Zink B, Hedges JR. The future of emergency medicine: an evolutionary perspective. Acad Med. 2010;85(3):490‐495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]