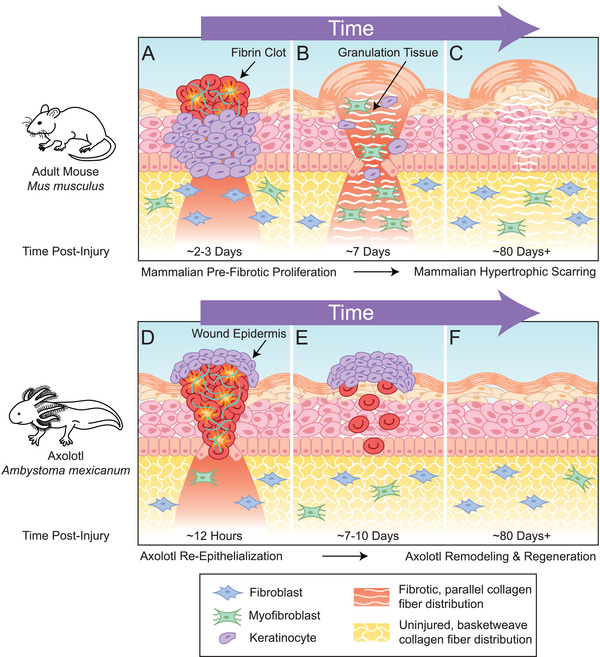

Figure 4.

Differences between regenerative and non‐regenerative species in proliferation and remodeling stages of wound healing. A) Schematic representation of mammalian prefibrotic cellular proliferation in the adult mouse, M. musculus ≈2–3 days postinjury. Keratinocytes (purple) migrate to the area where the fibrin clot is located and begin to proliferate. These keratinocytes aid in breaking down the fibrin clot and make way for a provisional matrix. Fibroblasts (blue) also proliferate and migrate at this stage and the combined proliferative effort begins the formation of granulation tissue. B) Fibroblasts lay down ECM proteins and produce collagen and fibronectin replacing the fibrin clot with granulation tissue. Fibroblasts differentiate into myofibroblasts (green) which connect to the existing ECM and contract. C) The collagen that is deposited in the area takes on a new, parallel pattern that does not resemble the original basketweave pattern of uninjured tissue. The final result is hypertrophic scarring. D) Schematic representation of the amphibian re‐epithelialization and proliferation response in the axolotl, A. mexicanum ≈12 h postinjury. Keratinocytes crawl over the wound and proliferate after the wound has been covered to make a thick epidermis. Fibroblasts also enter the wound area, proliferate, secrete ECM, and some differentiate into myofibroblasts which similarly contract. E) The wound epidermis continues to thicken, and the clot begins to resolve, leaving behind some residual plasma, blood, and inflammatory cells. F) This ECM then undergoes extensive remodeling during regeneration that renders tissue indistinguishable from uninjured tissue including normal, basketweave collagen distribution. Adapted with permission[ 26 ] Copyright 2018, Elsevier.