Abstract

Near-infrared (NIR) emitting probes with very large Stokes’ shifts play a crucial role in bioimaging applications, as the optical signals in this region exhibit high signal to background ratio and allow deeper tissue penetration. Herein we illustrate NIR-emitting probe 2 with very large Stokes’ shifts (Δλ ≈ 260 – 272 nm) by integrating the excited-state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) unit 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzoxazole (HBO) into a pyridinium derived cyanine. The ESIPT not only enhances the Stokes’ shifts but also improves the quantum efficiency of the probe 2 (фfl = 0.27 – 0.40 in DCM). The application of 2 in live cells imaging reveals that compound 2 stains mitochondria in eukaryotic cells, normal human lungs fibroblast (NHLF), Zebrafish’s neuromast hair cells, and support cells, and inner plasma membrane in prokaryotic cells, Escherichia coli (E. coli).

Keywords: near-infrared, ESIPT, fluorescence imaging, mitochondria, neuromast, plasma membrane

Introduction:

Fluorescent imaging plays an essential role in the visualization of the specific organelles, organs, and organisms, as fluorescence imaging can provide excellent spatial and temporal resolution. When coupling with suitable imaging reagents, the technique can be used to selectively display “targeting analytes” in cells, tissues, and even whole organisms.1–7 However, the fluorescence quality is strictly dependent on the photophysical properties of the fluorescent probes used in staining the sample.8 An ideal fluorescence probe should have the ability to target the specific organelles without perturbing their morphology and physiology. For example, mitochondria are the membrane-bound organelles that are considered as the powerhouse of eukaryotic cells and generate entire energy in animal cells in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by utilizing oxygen during oxidative phosphorylation.9–13 Moreover, mitochondria are also responsible for various functions such as cell signaling, cellular differentiation, cell cycle, and cell growth, and cell death and apoptosis.14–16 Therefore, the mitochondrial malfunction is associated with various diseases such as Alzheimer’s diseases, Parkinson’s diseases, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, cardiac myocyte death, and cancers.17–19

Another crucial cellular component is the plasma membrane that forms a boundary to protect the cell from the extracellular environment.20 The dynamic changes in the plasma membrane, due to the exchanging information and substances within a cell and surrounding, is the basic condition for endocytosis, exocytosis, nutrient transport, cell proliferation, and signal transmission, etc.21–22 The morphology of the plasma membrane is the direct indication of the cell status, such as partial swallowing, and rupture of the plasma membrane is the sign of cell apoptosis induced by drugs.22–23 In Prokaryotic cells, such as Escherichia coli (E.coli) (a Gram-negative bacteria), the morphology of the membrane consists of three layers: the outer membrane, the peptidoglycan layer, and the inner membrane. The peptidoglycan layer is occupied by viscous periplasmic space.24 A membrane is a lipid-bilayer that contain integral proteins. The outer membrane is made up of complex lipopolysaccharides, which are different from the inner membrane.25 Therefore, there is great interest in understanding the structure and functions of various cell organelles, such as the inner cytoplasmic membrane in prokaryotes or mitochondria in eukaryotes.

Hearing loss is one of the significant public health problems, and the degeneration of mechanosensory hair cells of the inner ear sensory epithelia is one of the leading causes of hearing loss in humans.26–27 The Zebrafish is emerging as a powerful tool for identifying the vertebrate gene and their functions.27–28 The Zebrafish lateral line has emerged as a powerful tool for drug-screening assays that cause or prevent the hair cells’ death.26 The lateral line consists of numerous mechanosensory organs called neuromast that comprise sensory hair cells and surrounding support cells. Although transgenic methods can be utilized for recognition of neuromasts,26, 29 the fluorescent dyes remains the easiest and the most accessible reagents used to visualize the lateral lines.

Fluorescence probes play a pivotal role in the study of biological cell organelles, as they exhibit high sensitivity and allow real-time observation.30–33 However, most of the fluorescence probes emitting in the visible region have limited application because of high phototoxicity and interference from the background autofluorescence of biological samples.34 Near-infrared (NIR) emitting fluorescence probes are useful for bioimaging applications, as they have a high signal-to-noise ratio, reduced photon scattering, and deeper tissue penetration depth.35–36 Current small-molecule fluorophores for NIR emission include BODIPY, rhodamine, benzofuran, and cyanines.37–38 However, these fluorophores exhibit a small Stokes’ shift (Δλ = 10 −60 nm), which prevents the optimum collection of the fluorescence signal and hamper the bioimaging application.39–41 Therefore, developing NIR emitting fluorescent probes with large Stokes’ shifts is desirable for improved sensitivity in fluorescence imaging. Also, NIR emitting probes with large Stokes’ shifts are useful for single excitation multicolor live-cell imaging, which plays an essential role in biological studies.42

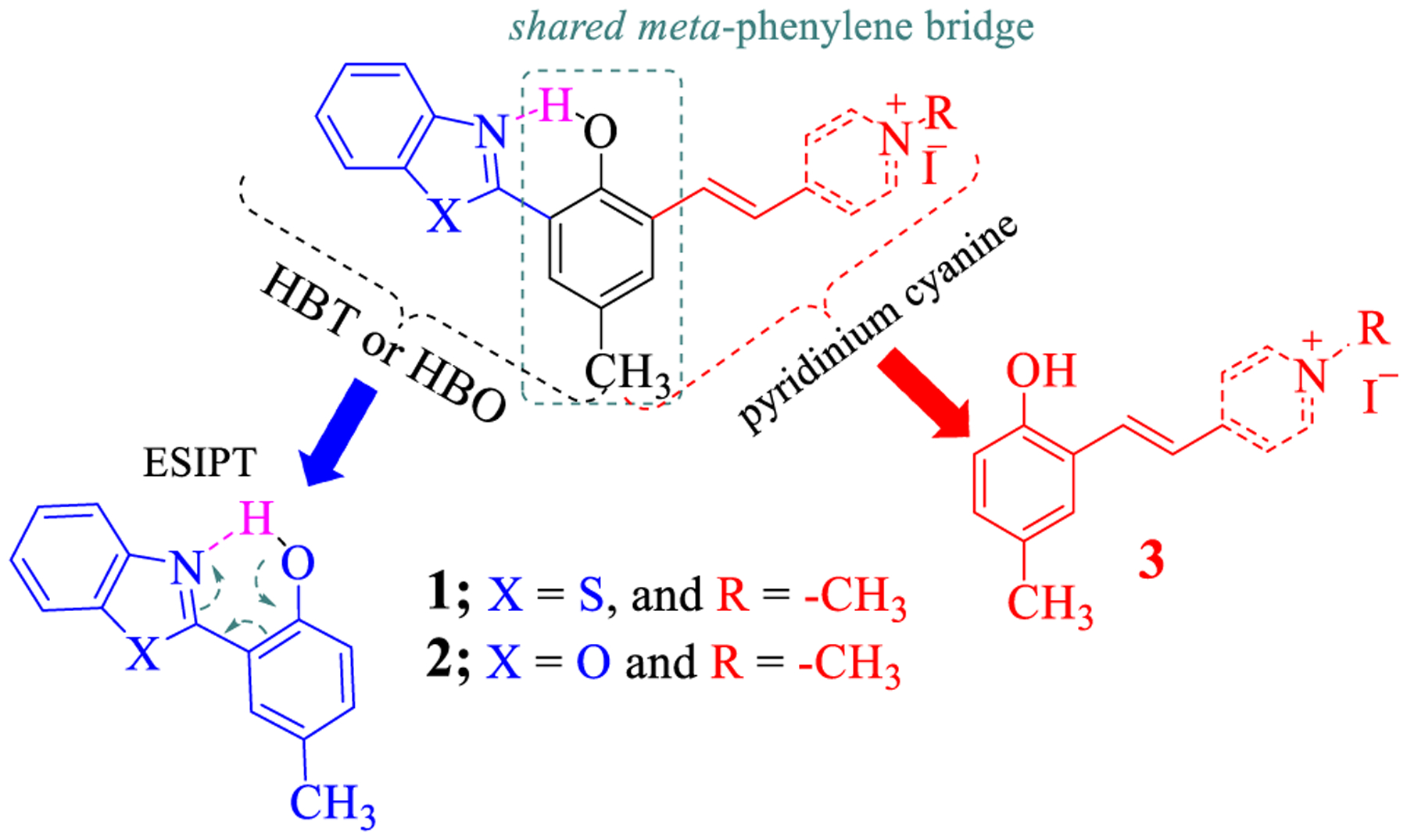

Recently, our group and others have synthesized NIR emitting probes by the integration of excited-state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) group; 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)benzoxazole (HBO) and 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)Benzothiazole (HBT), with hemicyanines via sharing meta-phenylene bridge, which gives NIR emission with very large Stokes’ shifts (Δλ = 234 – 272 nm).43–48 In this report, we present the synthesis of NIR-emitting molecular probe 2 by coupling ESIPT unit HBO with pyridinium styryl group via sharing meta-phenylene bridge for biological applications. Compound 2 exhibited NIR emission with very large Stokes’ shifts (Δλ = 260 – 272 nm), increased photostability, and improved quantum efficiency than its model compound 3 (pyridinium styryl hemicyanine chromophore without ESIPT). The substitution of ESIPT unit also increases the lipophilicity of the compound and hence help in cell penetrations. Thus, compound 2 stained mitochondria in eukaryotic cells (on normal human lungs fibroblast (NHLF)) neuromast hair cells and support cell of Zebrafish in vivo and inner plasma membrane of prokaryotic cells (on Escherichia coli (E.coli)).. Our study also revered that lipophilic dye 2 could be an excellent alternative for the investigation of protein diffusion in prokaryotic cells.

Result and discussion:

Synthesis and characterization of compound 2:

In a 50 mL round-bottomed flask, 120 mg (0.51 mmol) of compound 6 was dissolved in methanol (20 mL), and 0.5 ml of piperidine was added. The mixture was heated to 60°C, and 152 mg (0.60 mmol) of compound 5 were added, and the mixture was stirred at 60°C overnight. The solvent was then dried in a rotary evaporator, and the residual solid was washed with 50 ml ethyl acetate. The residue was filtered and dried to get 216 mg (~85% yield) of compound 2 (Scheme 1). The details for the synthesis of compound 5 can be found in our recent publication.45 The structure of 2 was confirmed by NMR (1H and 13C) (ESI Figure S1 and S2) spectroscopies and mass spectrometry (ESI Figure S3; calc mass: 343.1415). The resonance signal at 11.906 ppm was observed in 1H NMR, indicating that the hydroxyl proton is involved in the intramolecular hydrogen bond (Figures S1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Compound 2 (pyridinium cyanine coupled with HBO).

Optical properties:

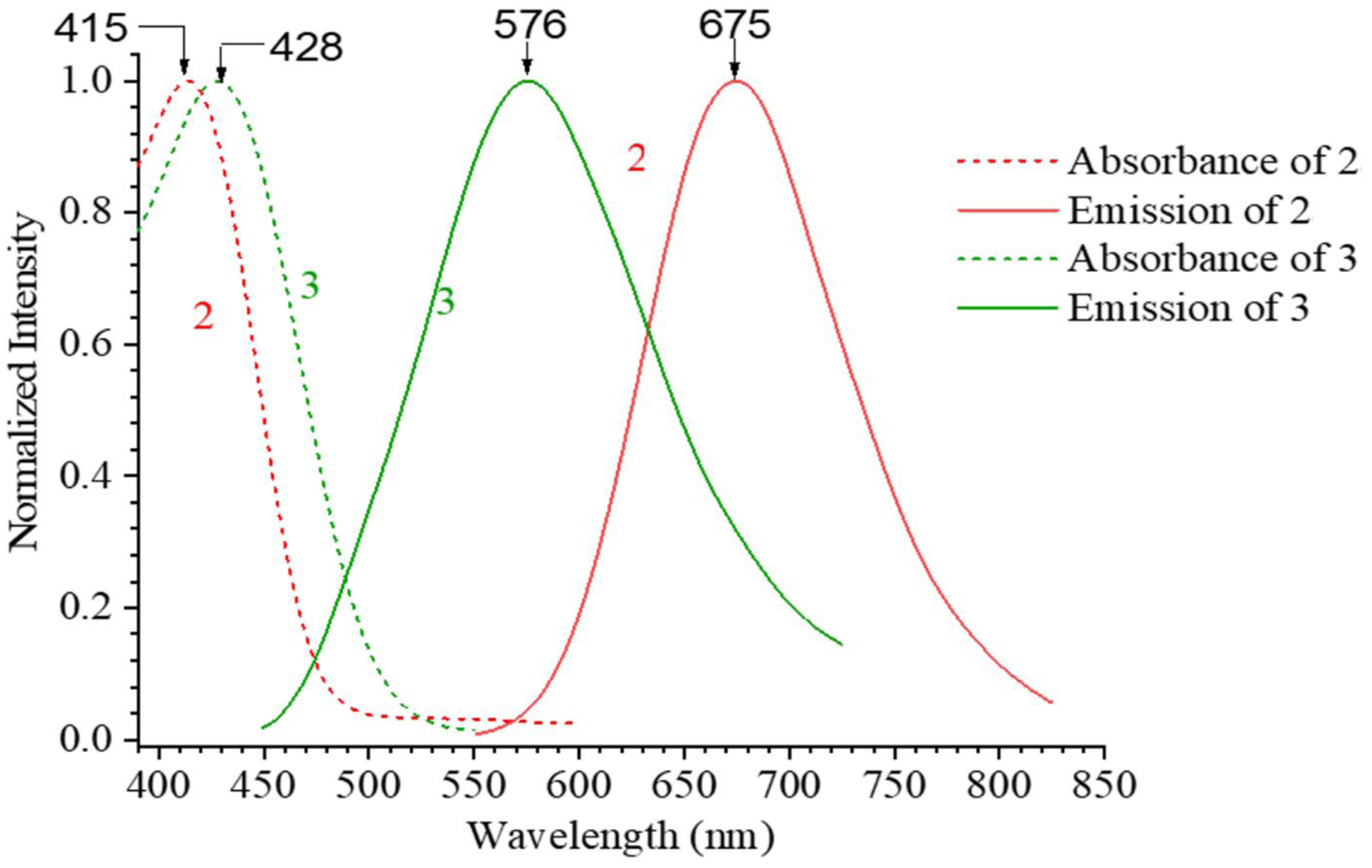

Compound 2 exhibited UV-absorption (λmax) at 415 nm (ε = 25809 M−1cm−1). The emission was observed at λem ≈ 675 nm for 2 in DCM, respectively, with a large Stokes’ Shifts (Δλ ≈ 260) (Figure 2). As a consequence of excited-state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT), the emission spectra of 2 were well separated from its absorption, leaving an optical window between 490 nm – 580 nm. This was in sharp contrast to compound 3, whose emission had a small Stokes’ shift. The emission wavelength of 2 was slightly affected by the polarity of solvents, with λem varying from 675 to 715 nm (ESI Figures S6). It should be noted that the π-conjugation length of 2 could be estimated by pyridinium styryl hemicyanine 3 (Figure 1), as they exhibited nearly identical λmax. However, the presence of an HBO unit enabled the ESIPT emission, which was responsible for the observed large Stokes shift.

Figure 2.

Photophysical properties of compounds 2 and 3 in DCM. Compound 3 shows normal emission, and 2 shows ESIPT emission.

Figure 1.

Structure of NIR emitting ESIPT probe.

Fluorescence quantum yield of 2 (фfl ≈0.05 to 0.27) was measured in different solvents with varying polarity (Table 1), which are significantly higher than that of 3 (фfl ≈0.003 to 0.10)44. The results further illustrated the impact of the ESIPT unit.

Table 1:

Optical properties of compounds 2 and 3 in different solvents.

| Solvents | Compound 2 | Compound 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abs. (λAbs) | Fl. Em. (λem) | Q.Y. (фfl) | Abs. (λAbs) | Fl. Em. (λem) | Q.Y. (фfl) | |

| DCM | 415 | 674 | 0.27 | 428 | 576 | 0.08 |

| DMF | 392 | 695 | 0.21 | 389 | 577 | 0.01 |

| DMSO | 392 | 695 | 0.27 | 398 | 588 | 0.02 |

| EtOH | 391 | 694 | 0.25 | |||

| MeCN | 386 | 683 | 0.28 | 389 | 557 | 0.100 |

| MeOH | 394 | 693 | 0.14 | 398 | 570 | 0.02 |

| THF | 394 | 690 | 0.15 | |||

| Water | 384 | 672 | 0.05 | 398 | 575 | 0.003 |

Low-Temperature Fluorescence:

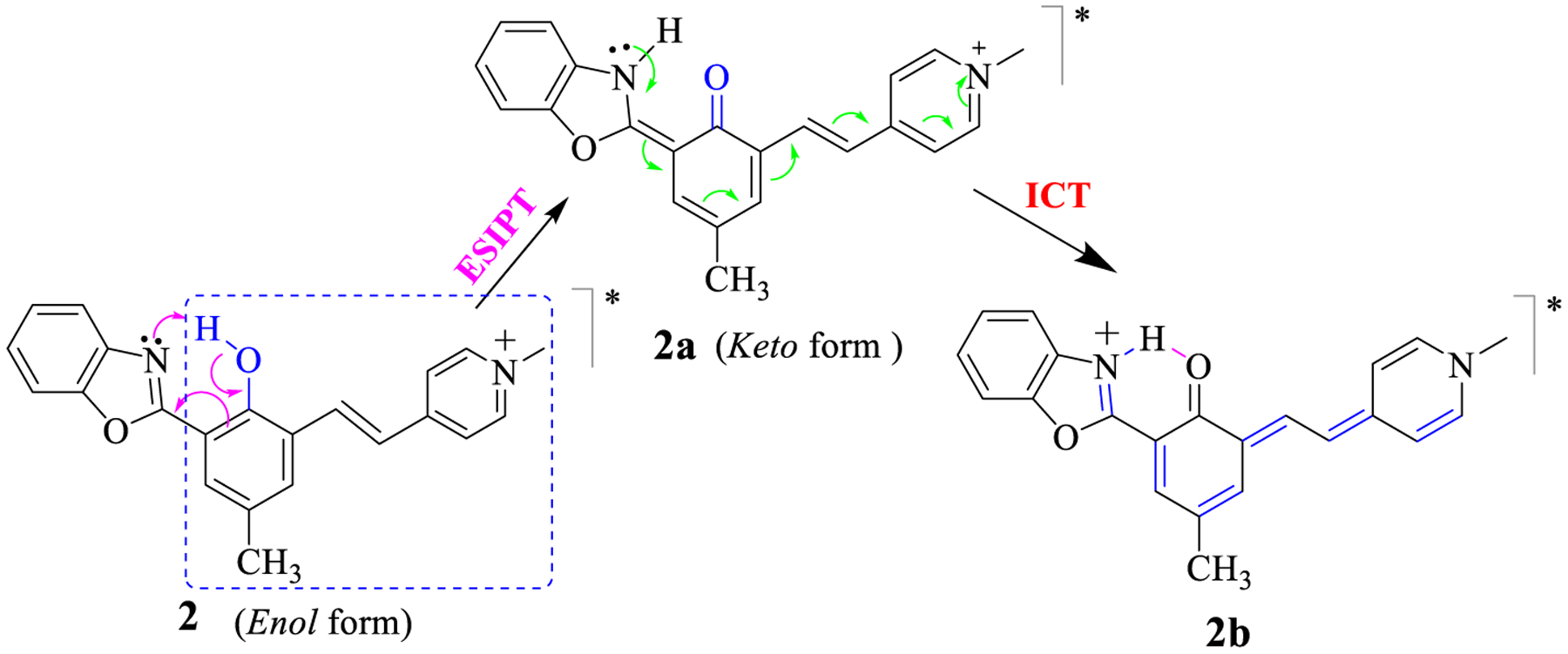

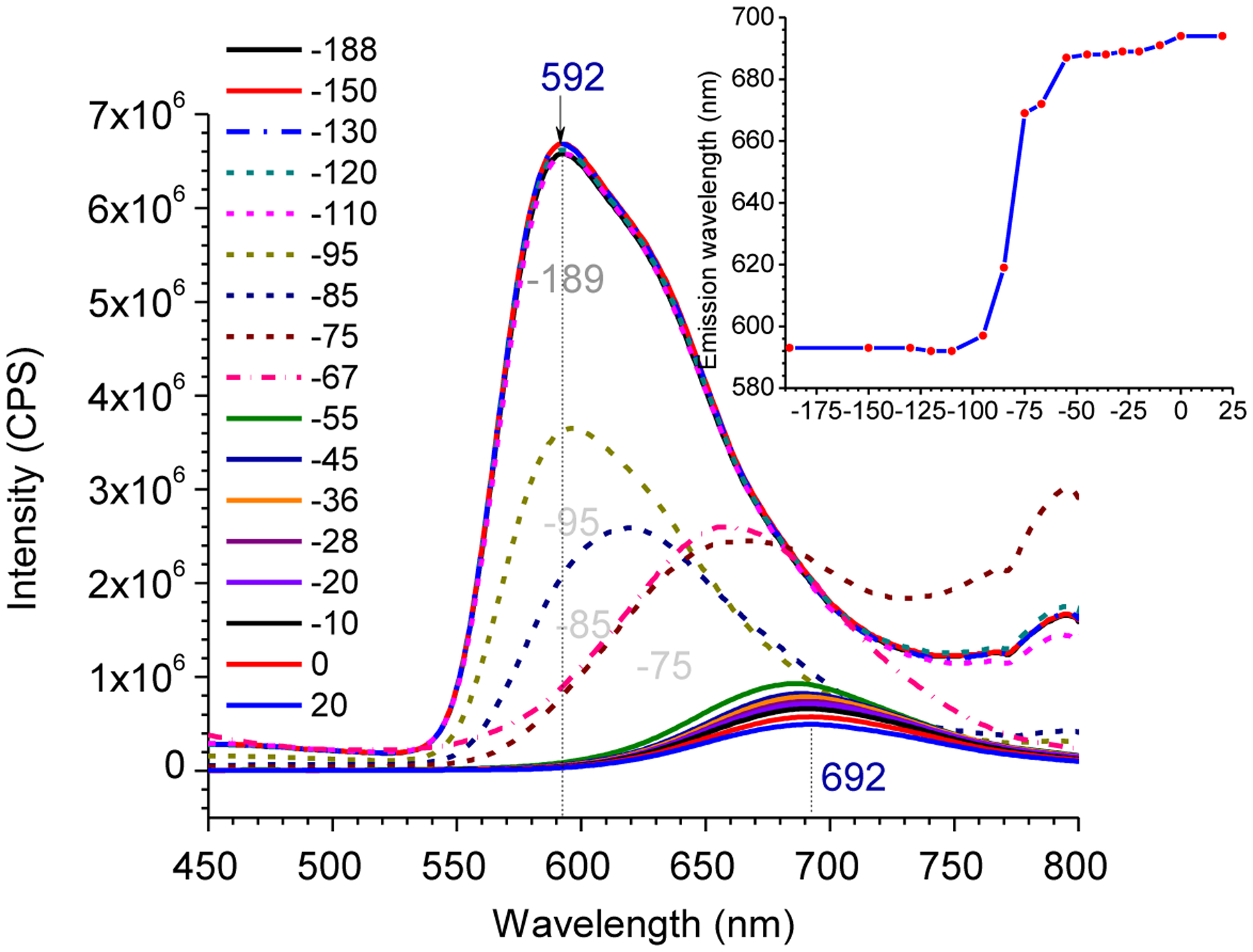

The observed large Stokes’ shifts of compound 2 could be associated with the ESIPT in structure 2, which led to its keto structure 2a. After undergoing ICT, 2a was transformed into 2b (Scheme 2). Low-temperature fluorescence spectra of 2 were acquired in order to shed some light on the photophysical process associated with the ESIPT and ICT. A dilute solution of 2 in ethanol was quickly cooled in liquid nitrogen in a quartz Dewar, and fluorescence spectra were acquired at different temperatures by gradually increasing the temperature over 2–3 hrs. At room temperature, the emission was observed at 692nm, which was blue-shifted to 592 nm at −189°C. When the temperature was gradually increased after cooling to −189°C, the spectral redshift was observed within a small range of temperatures from −110°C to −75°C (Figure 3), it was assumed ICT was not occurring when compound 2 was in the frozen solvent matrix that prevents the bond rotation and reorganization. However, ESIPT was not expected to shift the spectra at low temperature.49 Therefore, the large spectral shift (Δλem ≈ 100 nm) was attributed to the ICT within keto- tautomer 2b formed from 2 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Structures of the enol and keto tautomers of 2 that undergo ESIPT and ICT. The dotted squire is the effective chromophore of compound 2.

Figure 3.

Low-temperature fluorescence of compound 2a in EtOH

Cell imaging study by using compound 2:

The attractive photophysical properties such as high fluorescence quantum yield, NIR emission with large Stokes’ Shifts, and low toxicity of compound 2 (IC50 = 66.45 μM) (ESI Figure S7) encouraged us to investigate its possible applications. Therefore, compound 2 was used to stain normal human lungs fibroblast (NHLF) cells and E. coli bacterial cells. The confocal fluorescence microscopic imaging of NHLF cells revealed strong non-uniform fluorescence signals from the perinuclear region (Figure 4 second column, ESI Figure S11). Co-staining of 2 with MitoTracker red confirmed that 2 exhibited good selectivity to stain mitochondria (Figure 4 third column, ESI Figure S12) with the Pearson’s colocalization coefficients of 0.92.

Figure 4.

Confocal fluorescence images of Normal Human Lungs Fibroblast (NHLF) cells costained with compound 2 (1 μM) and MitoTracker Red (200 nM) (Top row) acquired at 60 × magnification of the oil-drop objective lens. The bottom row is four times digitally enhanced images of a portion enclosed in a white box of the top row The compound 2 was excited at 405 nm laser with emission filters of 700–720 nm, and the Mitotracker Red was excited at 561 nm laser with the emission bandpass filters of 595/50 nm.

Compound 2 was further used to stain the prokaryotic cells, E. coli, in order to discover its broader applications. Thus E. coli cells were incubated with 2 at 37°C for 15 minutes and the images were recorded on a confocal fluorescence microscope. Interestingly, the bright fluorescence signals were observed from the peripheral region of the E. coli cells indicating that it stained the membrane of the bacterial cells (Figure 5A, and ESI Figures S10 and S11A).). It should be noted that the cytoplasmic membrane of gram-negative bacteria, E. coli bacteria, possesses outer and inner membranes. In order to further identify the location of the fluorescent dye, the E. coli (DGC-102) cells were plasmolyzed by using a hypertonic NaCl solution (Figure 5A – 5C) and 0.6 M sucrose solution (Figure 5D – 5G). Thus, the cells were treated with 2, and 0.4 M NaCl solution and/ or 0.6 M sucrose solution were added to induce osmotic shock.50 Addition of the hypertonic NaCl/sucrose solutions would induce water efflux through a semipermeable membrane, causing the shrinkage of the inner membrane of cells.51 The plasmolyzed bays were observed upon the addition of the NaCl solution and/or sucrose solution (Figure 5 B, C, and D ESI Figure S11B – S11D), indicating that the dye selectively stained the inner cytoplasmic membrane. This study implies that different membrane properties, including lipid and protein diffusion, could be investigated using membrane targeting compound 2.52

Figure 5.

E. coli cells labeled and plasmolyzed. (A) Healthy cell stained with compound 2 without using NaCl solution, (B & C) plasmolyzed Cells with 0.4M NaCl solution, which showed dark plasmolyzed bays in the region of plasmolysis shown with the arrows, and (D-G) fluorescence images of plasmolyzed cells with 0.6M sucrose solution along with bright fields. Some cells have multiple bays indicating more than one plasmolyzed area (B & F). The original images were acquired under 100x magnification of the oil-drop objective lens. The compound 2 was excited at 405 nm laser with emission filters of 700–720 nm.

Stability of Dye:

Rapid photobleaching of a dye is a common problem for fluorescence dyes since long-term live-cell imaging requires excitation with laser for an extended time in the microscope. Therefore, photostability is a significant parameter in real-time live-cell imaging. In order to evaluate how fast or slow the fluorophore is bleached, photobleaching behavior (photostability) of compound 2 was examined by illuminating the bacterial (E. coli) cells stained with dye 2 with a high-intensity laser beam over 60 minutes with continuous scanning. Since the scanned sample area contained about 40 bacteria, each of the individual cells was irradiated for about 1.5 minutes in average. The compound 2 exhibited relatively constant stability for about 60 minutes for individual cells when analyzed in real-time cell imaging (Figure 6A and 6B). The relative photostability of compound 1 was also compared with compound 2 (Figure 6C and ESI Figure S16). It was observed that compound 1 initially had brighter emission than compound 2; however, the intensity of the cell imaging stained with compound 1 dropped significantly than compound 2 over time with continuous laser scanning. This implies that the presence of HBO in compound 2 makes it more photostable than the HBT in compound 1.

Figure 6.

A) Confocal fluorescence images of E. coli cells taken within 1 hour period to observe the relative intensity of compound 2, B) The plot of the relative intensity measured over 90 minutes for compound 2 vs time, and C) Comparison of relative intensities between compound 1 and 2. The images of cells in “A” were acquired under 100x magnification of the oil-drop objective lens. The compound was excited at 405 nm laser with emission filters of 700–720 nm.

Fluorescence imaging of Zebrafish using compound 2 in vivo:

Our previous work shows that compound 1 was useful for the developmental study of the neuromast hair cells and supporting cells of Zebrafish.26 Encouraged by its low toxicity and improved photostability, we decided to explore the further use of 2 for zebrafish imaging. Thus, the zebrafish embryos of 36 – 96 hours of post-fertilization (hpf) were incubated with 2 for 30 minutes at room temperature, and confocal fluorescence microscopic imaging was acquired. The microscopic imaging revealed that strong fluorescence signals were observed from the head region around the eyes and along the lateral lines of the body from head to tail of the embryos.(48 – 96 hpf) (Figure 7 for 72 hpf). The structure in the digitally enhanced image (Figure 7 bottom row and Figure S17) also revealed that the compound 2 selectively labeled the neuromast hair cells and support cells. Staining neuromast hair cells and support cells by compound 2 were also confirmed by colocalizing with commercially available neuromast selective dye 4-(4- Diethylaminostyryl)-1-methyl pyridinium iodide (4-Di-2-ASPI) (Figure 7, D – F).

Figure 7.

Confocal fluorescence microscopic imaging of 72 hpf zebrafish stained with compound 2 and commercial dye 4-Di-2-ASPI, A) 4-Di-2-ASPI, B) Compound 2, C) merged A and B under 10x magnification and D – F) High magnification (digitally enhanced) images of the spots in head and tail regions shown with yellow arrows in A – C respectively. The excitation wavelength for compound 2 was 405 nm with the emission filters of 700–720 nm, and the excitation/emission wavelength for 4-Di-2-ASPI was 488/561 nm, respectively.

Conclusion:

NIR emitting probe 2 was synthesized by integrating the ESIPT unit with a pyridinium styryl-derived cyanine unit, which exhibited very large Stokes’ shifts (Δλ ≈ 260 nm). The dye showed high quantum efficiency (фfl = 0.27 in DCM), increased photostability, and high biocompatibility (IC50 = 66.45 μM). The lipophilic cationic probe 2 exhibited excellent selectivity to mitochondria in eukaryotic cells and Zebrafish’s neuromast hair cells and support cells. The selectivity towards mitochondria could be assumed to be due to the presence of a positive charge in the molecule, which could have been attracted by the negative potential gradient (coulombic attraction) in the mitochondria. In addition, probe 2 also exhibited excellent selectivity to the inner plasma membrane of prokaryotic cells, as shown in E. coli (a Gram-negative bacteria). Since the prokaryotic bacterial cells, E. coli, do not have membrane-bound mitochondria, the lipophilicity of probe 2 could have been driving the dye into the inner plasma membrane of the E. coli cells.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A highly fluorescent NIR-emitting probe with large Stokes shift.

Fluorescent probes for confocal microscopy imaging in live cells.

A highly selective probe with bright red emission for neuromast imaging.

Acknowledgment:

We thank the support from NIH (Grant no. 1R15GM126438-01A1). Y. P. also acknowledges partial support from Coleman Endowment from The University of Akron. We also thank Jason O’Neil for acquiring mass spectra for related compounds, and Yonghao Li of University of Akron for verification of some synthesis process.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Reference:

- 1.Ke C-S; Fang C-C; Yan J-Y; Tseng P-J; Pyle JR; Chen C-P; Lin S-Y; Chen J; Zhang X; Chan Y-H, Molecular Engineering and Design of Semiconducting Polymer Dots with Narrow-Band, Near-Infrared Emission for in Vivo Biological Imaging. ACS Nano 2017, 11 (3), 3166–3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L; Frei MS; Salim A; Johnsson K, Small-Molecule Fluorescent Probes for Live-Cell Super-Resolution Microscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2019, 141 (7), 2770–2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun W; Guo S; Hu C; Fan J; Peng X, Recent Development of Chemosensors Based on Cyanine Platforms. Chemical Reviews 2016, 116 (14), 7768–7817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sedgwick AC; Wu L; Han H-H; Bull SD; He X-P; James TD; Sessler JL; Tang BZ; Tian H; Yoon J, Excited-state intramolecular proton-transfer (ESIPT) based fluorescence sensors and imaging agents. Chemical Society Reviews 2018, 47 (23), 8842–8880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagaya T; Nakamura YA; Choyke PL; Kobayashi H, Fluorescence-Guided Surgery. Frontiers in Oncology 2017, 7 (314). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren H; Huo F; Wu X; Liu X; Yin C, An ESIPT-induced NIR fluorescent probe to visualize mitochondrial sulfur dioxide during oxidative stress in vivo. Chemical Communications 2021, 57 (5), 655–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang X; Wang Y; Liu R; Zhang Y; Tang J; Yang E.-b.; Zhang D; Zhao Y; Ye Y, A novel ICT-based two photon and NIR fluorescent probe for labile Fe2+ detection and cell imaging in living cells. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2019, 288, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gong Y-J; Zhang X-B; Mao G-J; Su L; Meng H-M; Tan W; Feng S; Zhang G, A unique approach toward near-infrared fluorescent probes for bioimaging with remarkably enhanced contrast. Chemical Science 2016, 7 (3), 2275–2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu Z; Xu L, Fluorescent probes for the selective detection of chemical species inside mitochondria. Chemical Communications 2016, 52 (6), 1094–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abeywickrama CS; Baumann HJ; Alexander N; Shriver LP; Konopka M; Pang Y, NIR-emitting benzothiazolium cyanines with an enhanced stokes shift for mitochondria imaging in live cells. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry 2018, 16 (18), 3382–3388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahal D; McDonald L; Pokhrel S; Paruchuri S; Konopka M; Pang Y, A NIR-emitting cyanine with large Stokes shifts for live cell imaging: large impact of the phenol group on emission. Chemical Communications 2019, 55 (88), 13223–13226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song X; Bai S; He N; Wang R; Xing Y; Lv C; Yu F, Real-Time Evaluation of Hydrogen Peroxide Injuries in Pulmonary Fibrosis Mice Models with a Mitochondria-Targeted Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probe. ACS Sensors 2021, 6 (3), 1228–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo X; Wang R; Lv C; Chen G; You J; Yu F, Detection of Selenocysteine with a Ratiometric near-Infrared Fluorescent Probe in Cells and in Mice Thyroid Diseases Model. Analytical Chemistry 2020, 92 (1), 1589–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Z; Zhang D; He X; Huang Y; Shao H, Transport of Calcium Ions into Mitochondria. Curr Genomics 2016, 17 (3), 215–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McBride HM; Neuspiel M; Wasiak S, Mitochondria: More Than Just a Powerhouse. Current Biology 2006, 16 (14), R551–R560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y; Zhou J; Wang L; Hu X; Liu X; Liu M; Cao Z; Shangguan D; Tan W, A Cyanine Dye to Probe Mitophagy: Simultaneous Detection of Mitochondria and Autolysosomes in Live Cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016, 138 (38), 12368–12374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu B; Shah M; Zhang G; Liu Q; Pang Y, Biocompatible Flavone-Based Fluorogenic Probes for Quick Wash-Free Mitochondrial Imaging in Living Cells. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2014, 6 (23), 21638–21644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long L; Huang M; Wang N; Wu Y; Wang K; Gong A; Zhang Z; Sessler JL, A Mitochondria-Specific Fluorescent Probe for Visualizing Endogenous Hydrogen Cyanide Fluctuations in Neurons. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2018, 140 (5), 1870–1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang X; Han X; Zhang Y; Liu J; Tang J; Zhang D; Zhao Y; Ye Y, Imaging Hg2+-Induced Oxidative Stress by NIR Molecular Probe with “Dual-Key-and-Lock” Strategy. Analytical Chemistry 2020, 92 (17), 12002–12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C; Jin S; Yang K; Xue X; Li Z; Jiang Y; Chen W-Q; Dai L; Zou G; Liang X-J, Cell Membrane Tracker Based on Restriction of Intramolecular Rotation. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2014, 6 (12), 8971–8975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koivusalo M; Welch C; Hayashi H; Scott CC; Kim M; Alexander T; Touret N; Hahn KM; Grinstein S, Amiloride inhibits macropinocytosis by lowering submembranous pH and preventing Rac1 and Cdc42 signaling. Journal of Cell Biology 2010, 188 (4), 547–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X; Wang C; Jin L; Han Z; Xiao Y, Photostable Bipolar Fluorescent Probe for Video Tracking Plasma Membranes Related Cellular Processes. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2014, 6 (15), 12372–12379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fadeel B; Xue D, The ins and outs of phospholipid asymmetry in the plasma membrane: roles in health and disease. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 2009, 44 (5), 264–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruiz N; Kahne D; Silhavy TJ, Advances in understanding bacterial outer-membrane biogenesis. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2006, 4, 57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bos MP; Tefsen B; Geurtsen J; Tommassen J, Identification of an outer membrane protein required for the transport of lipopolysaccharide to the bacterial cell surface. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101 (25), 9417–9422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald L; Dahal D; Konopka M; Liu Q; Pang Y, An NIR emitting styryl dye with large Stokes shift to enable co-staining study on zebrafish neuromast hair cells. Bioorganic Chemistry 2019, 89, 103040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris JA; Cheng AG; Cunningham LL; MacDonald G; Raible DW; Rubel EW, Neomycin-Induced Hair Cell Death and Rapid Regeneration in the Lateral Line of Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 2003, 4 (2), 219–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin X; Chen Y; Qin W; Zhang C; Wang S; Liu K; Kong F, Rational design of a unique palladium coordination polymer with distinctive fluorescence and its application for CO sensing in living Zebrafish. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 419, 129538. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haehnel-Taguchi M; Akanyeti O; Liao JC, Behavior, Electrophysiology, and Robotics Experiments to Study Lateral Line Sensing in Fishes. Integr Comp Biol 2018, 58 (5), 874–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang W; Kwok RTK; Chen Y; Chen S; Zhao E; Yu CYY; Lam JWY; Zheng Q; Tang BZ, Real-time monitoring of the mitophagy process by a photostable fluorescent mitochondrion-specific bioprobe with AIE characteristics. Chemical Communications 2015, 51 (43), 9022–9025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyrychenko A, Using fluorescence for studies of biological membranes: a review. Methods and Applications in Fluorescence 2015, 3 (4), 042003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin X; Qin W; Chen Y; Bao L; Li N; Wang S; Liu K; Kong F; Yi T, Construction of a multi-signal near-infrared fluorescent probe for sensing of hypochlorite concentration fluctuation in living animals. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2020, 324, 128732. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin X; Chen Y; Bao L; Wang S; Liu K; Qin W.-d.; Kong F, A two-photon near-infrared fluorescent probe for imaging endogenous hypochlorite in cells, tissue and living mouse. Dyes and Pigments 2020, 174, 108113. [Google Scholar]

- 34.He S; Song J; Qu J; Cheng Z, Crucial breakthrough of second near-infrared biological window fluorophores: design and synthesis toward multimodal imaging and theranostics. Chemical Society Reviews 2018, 47 (12), 4258–4278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo Z; Park S; Yoon J; Shin I, Recent progress in the development of near-infrared fluorescent probes for bioimaging applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2014, 43 (1), 16–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altınoǧlu EI; Russin TJ; Kaiser JM; Barth BM; Eklund PC; Kester M; Adair JH, Near-Infrared Emitting Fluorophore-Doped Calcium Phosphate Nanoparticles for In Vivo Imaging of Human Breast Cancer. ACS Nano 2008, 2 (10), 2075–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang S; Wu T; Fan J; Li Z; Jiang N; Wang J; Dou B; Sun S; Song F; Peng X, A BODIPY-based fluorescent dye for mitochondria in living cells, with low cytotoxicity and high photostability. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry 2013, 11 (4), 555–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang X; Sun Q; Huang Z; Huang L; Xiao Y, Immobilizable fluorescent probes for monitoring the mitochondria microenvironment: a next step from the classic. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2019, 7 (17), 2749–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dahal D; McDonald L; Pokhrel S; Paruchuri S; Konopka M; Pang Y, A NIR-Emitting Cyanine with Large Stokes Shifts for Live Cell Imaging: Large Impact of Phenol Group on Emission. Chemical Communications 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu W; Ma H; Hou B; Zhao H; Ji Y; Jiang R; Hu X; Lu X; Zhang L; Tang Y; Fan Q; Huang W, Engineering Lysosome-Targeting BODIPY Nanoparticles for Photoacoustic Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy under Near-Infrared Light. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2016, 8 (19), 12039–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang B; Cui X; Zhang Z; Chai X; Ding H; Wu Q; Guo Z; Wang T, A six-membered-ring incorporated Si-rhodamine for imaging of copper(ii) in lysosomes. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry 2016, 14 (28), 6720–6728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piatkevich Kiryl D.; English Brian P.; Malashkevich Vladimir N.; Xiao H; Almo Steven C.; Singer Robert H.; Verkhusha Vladislav V., Photoswitchable Red Fluorescent Protein with a Large Stokes Shift. Chemistry & Biology 2014, 21 (10), 1402–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dahal D; McDonald L; Bi X; Abeywickrama C; Gombedza F; Konopka M; Paruchuri S; Pang Y, An NIR-emitting lysosome-targeting probe with large Stokes shift via coupling cyanine and excited-state intramolecular proton transfer. Chemical Communications 2017, 53 (26), 3697–3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dahal D; Ojha KR; Alexander N; Konopka M; Pang Y, An NIR-emitting ESIPT dye with large stokes shift for plasma membrane of prokaryotic (E. coli) cells. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2018, 259, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dahal D; Pokhrel S; McDonald L; Bertman K; Paruchuri S; Konopka M; Pang Y, NIR-Emitting Hemicyanines with Large Stokes’ Shifts for Live Cell Imaging: from Lysosome to Mitochondria Selectivity by Substituent Effect. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2019, 2 (9), 4037–4043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo Y; Dahal D; Kuang Z; Wang X; Song H; Guo Q; Pang Y; Xia A, Ultrafast excited state intramolecular proton/charge transfers in novel NIR-emitting molecules. AIP Advances 2019, 9 (1), 015229. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang L; He P; Yan X; Sun J; Zhong K; Hou S; Bian Y, A mitochondria-targetable fluorescent probe for ratiometric detection of SO2 derivatives and its application in live cell imaging. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2017, 247, 421–427. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu P; Gao T; Liu M; Zhang H; Zeng W, A novel excited-state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) dye with unique near-IR keto emission and its application in detection of hydrogen sulfide. Analyst 2015, 140 (6), 1814–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Das K; Sarkar N; Ghosh AK; Majumdar D; Nath DN; Bhattacharyya K, Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Transfer in 2-(2-Hydroxyphenyl)benzimidazole and -benzoxazole: Effect of Rotamerism and Hydrogen Bonding. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 1994, 98 (37), 9126–9132. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scheie PO, Plasmolysis of Escherichia coli B/r with Sucrose. Journal of Bacteriology 1969, 98 (2), 335–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pilizota T; Shaevitz Joshua W., Plasmolysis and Cell Shape Depend on Solute Outer-Membrane Permeability during Hyperosmotic Shock in E. coli. Biophysical Journal 2013, 104 (12), 2733–2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nenninger A; Mastroianni G; Robson A; Lenn T; Xue Q; Leake MC; Mullineaux CW, Independent mobility of proteins and lipids in the plasma membrane of Escherichia coli. Molecular Microbiology 2014, 92 (5), 1142–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.