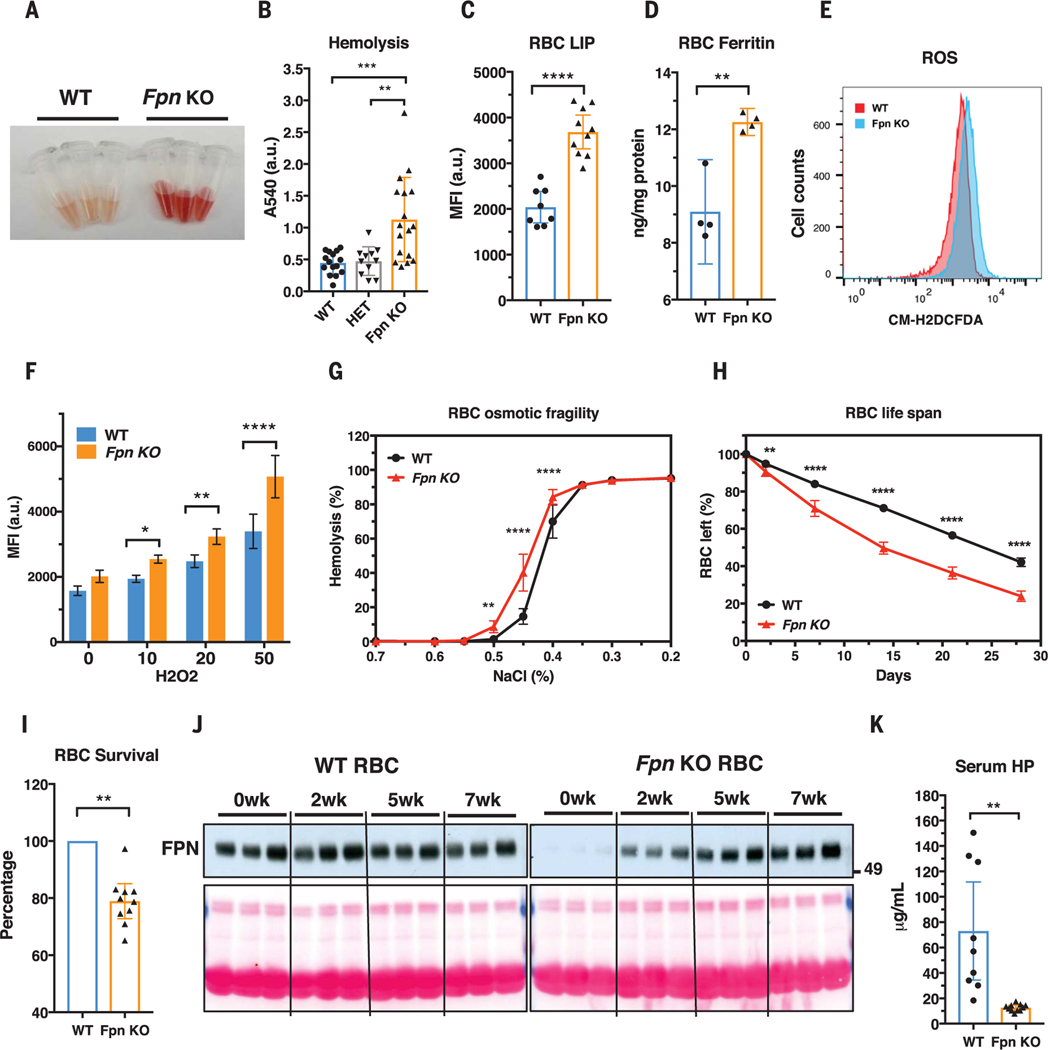

Fig. 2. Fpn knockout in erythroblasts leads to RBC iron overload and intravascular hemolysis.

(A) Plasma of WT and Fpn KO mice after storing blood samples for 20 hours at 4°C showed increased hemolysis of Fpn KO RBCs. (B) Free-hemoglobin levels in plasma of WT, heterozygote (HET), and Fpn KO mice. Significance determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. A540, absorption at 540 nm; a.u., arbitrary units. (C) Labile iron pool (LIP) and (D) ferritin levels were dramatically increased in RBCs of Fpn KO mice. MFI, median fluorescence intensity. (E) Representative flow cytometry of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in RBCs of WT and Fpn KO mice and (F) quantification of ROS levels in RBCs of WT and Fpn KO mice after stimulation by H2O2 at different micromolar concentrations. n = 8. CM-H2DCFCA is a ROS indicator. (G) Osmotic fragility of RBCs, n = 9. (H) RBC life span of Fpn KO mice, n = 9. (I) Survival of ex vivo biotin-labeled WT and Fpn KO RBCs in the same WT mice (fig. S9). (J) Immunoblots showing FPN levels in the aging process of the RBCs of three WT and three Fpn KO mice in vivo. Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin was injected intravenously to label all RBCs, and after 0, 2, 5, and 7 weeks (wk), biotinylated RBCs were purified and FPN levels were then measured with immunoblots in total lysates. Ponceau S staining (bottom) is shown as a loading control. The increase of FPN levels in RBCs of Fpn conditional KO mice indicated that the few FPN-expressing RBCs survived longer than Fpn-null RBCs and were proportionally enriched over time (fig. S10). (K) Serum haptoglobin (HP) was depleted in Fpn KO mice. Data are presented as mean ± 95% CI. Significances for (F) to (H) were determined by two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test; significances for (I) and (K) were determined by Welch’s t test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.