Abstract

Thousands of nuclear and cytosolic proteins are modified with a single β-N-acetylglucosamine on serine and threonine residues in mammals, a modification termed O-GlcNAc. This modification is essential for normal development and plays important roles in virtually all intracellular processes. Additionally, O-GlcNAc is involved in many disease states, including cancer, diabetes, and X-linked intellectual disability. Given the myriad of functions of the O-GlcNAc modification, it is therefore somewhat surprising that O-GlcNAc cycling is mediated by only two enzymes: the O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT), which adds O-GlcNAc, and the O-GlcNAcase (OGA), which removes it. A significant outstanding question in the O-GlcNAc field is how do only two enzymes mediate such an abundant and dynamic modification. In this review, we explore the current understanding of mechanisms for substrate selection for the O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes. These mechanisms include direct substrate interaction with specific domains of OGT or OGA, selection of interactors via partner proteins, posttranslational modification of OGT or OGA, nutrient sensing, and localization alteration. Altogether, current research paints a picture of an exquisitely regulated and complex system by which OGT and OGA select substrates. We also make recommendations for future work, toward the goal of identifying interaction mechanisms for specific substrates that may be able to be exploited for various research and medical treatment goals.

Keywords: O-GlcNAc, OGA, OGT, substrate selection

Introduction

Thousands of proteins are posttranslationally modified with O-GlcNAc, consisting of a single β-N-acetylglucosamine attached to serine or threonine residues. This modification, discovered over 30 years ago (Torres and Hart 1984; Holt and Hart 1986), has since been implicated in nearly every intracellular biological process and many disease states. O-GlcNAc is involved in the regulation of cellular nutrient sensing, transcription, translation, and many other fundamental cellular processes (Hardville and Hart 2014). Furthermore, O-GlcNAc has been shown to play important roles in a myriad of diseases that affect millions worldwide, including many forms of cancer, neurological disorders including Alzheimer’s disease, X-linked intellectual disability, Parkinson’s disease, and diabetes (Vaidyanathan et al. 2014; Pravata et al. 2020). Such a modification with these many substrates and roles must be exquisitely regulated. This leads to one of the great mysteries of this field: How does regulation of the O-GlcNAc modification occur?

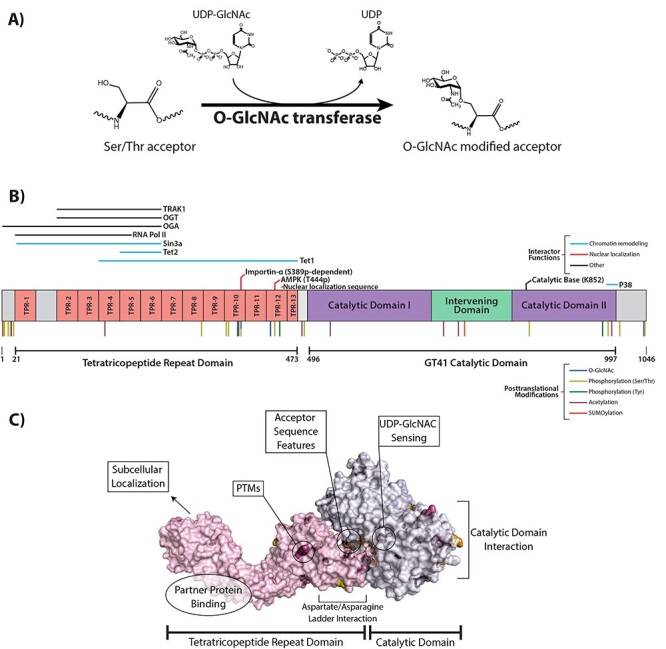

In the mammalian cell, the focus of this review, there are only two enzymes responsible for O-GlcNAc cycling: the O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT), which adds the modification (Figure 1A), and the O-GlcNAcase (OGA), which removes it (Figure 2A). This is in direct contrast to the other highly prevalent intracellular posttranslational modification, phosphorylation, which modifies a similar number of proteins as O-GlcNAc (and in fact often directly competes for O-GlcNAc sites), but is instead mediated by hundreds of protein kinases and dozens of protein phosphatases. In order for OGT and OGA to single-handedly modulate such an abundant and finely-tuned protein modification, the enzymes must exhibit complex mechanisms of substrate selection.

Fig. 1.

The O-GlcNAc transferase. (A) Schematic of the addition of O-GlcNAc to an acceptor substrate by OGT. (B) Linear representation of the structure and domains of OGT. Interacting proteins and their location of interaction are shown above the structure. Known posttranslational modifications are shown below. (C) Possible mechanisms of OGT substrate selection, shown on a surface and cartoon representation of OGT in complex with a substrate peptide. A structure for the N-terminal TPR domain (PDB: 1W3B, Jinek et al. 2004) was aligned with an overlapping structure containing the remaining C-terminal TPR and catalytic domains (PDB: 4GYY, Lazarus et al. 2012) using PyMOL 2.4.1.

Fig. 2.

The O-GlcNAcase. (A) Schematic of the removal of O-GlcNAc from an acceptor substrate by OGA. (B) Linear representation of the structure and domains of OGA. Interacting proteins and their location of interaction are shown above the structure. Known posttranslational modifications are shown below. (C) Possible mechanisms of OGA substrate selection, shown on a surface and cartoon representation of OGA in complex with a substrate O-GlcNAc-modified glycopeptide. A structure of OGA in complex with thiamet-G (PDB: 5UN93) was aligned with a structure of an OGA D175N mutant in complex with a glycopeptide substrate (PDB: 5VVU, Li et al. 2017a) using PyMOL 2.4.1.

Significant work has attempted to define various mechanisms of OGT and OGA substrate interaction, revealing a complex network of both global and specific methods by which O-GlcNAc substrates are selected. In this review, we explore biochemical evidence for various hypotheses that comprise our current understanding of how protein selection for O-GlcNAc modification occurs. We also suggest future avenues for research to continue defining these mechanisms. For the reader interested in information on global cellular processes and disease mechanisms affected by the O-GlcNAc modification, we refer to the excellent review published by the founder of the O-GlcNAc field, Dr. Gerald Hart (Hart 2019).

The O-GlcNAc transferase

Enzyme features

The O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) is encoded by a single gene found on the X chromosome (Shafi et al. 2000). It consists of two primary domains: the N-terminal tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain and the C-terminal catalytic domain, which contains the glycosyltransferase activity (Figure 1B). The TPR domain consists of individual tetratricopeptide repeats, each 34 amino acids in length. The OGT gene encodes three different isoforms differing only in the length of their TPR domains. The full-length OGT (ncOGT) consists of 13.5 tetratricopeptide repeats (Kreppel et al. 1997; Lubas and Hanover 2000). The mitochondrial OGT (mOGT), localized only to the mitochondria and of debated importance/catalytic activity (Love et al. 2003; Trapannone et al. 2016; Sacoman et al. 2017), has 9.5 TPRs. Finally, short OGT (sOGT) consists of 3.5 TPRs and has very limited research on its role and function (Liu et al. 2019). Since the vast majority of work on OGT substrate selectivity has used the ncOGT, and since ncOGT seems to be responsible for the majority of intracellular O-GlcNAc over the other isoforms, this review will focus on this isoform.

A variety of hypotheses, not mutually exclusive, on how OGT is able to select from among thousands of substrates have arisen over several decades of research. Each of the major hypotheses is discussed below and summarized in Figure 1C.

Substrate selection: consensus sequence

The potential for identifying a consensus sequence that dictates where the O-GlcNAc modification can be made is appealing, considering that much of secretory pathway N-linked glycosylation is dictated by consensus sequence. Characterization done upon the discovery of the OGT enzyme suggested that high enrichment of S/T residues, along with a proline and acidic residues adjacent to the glycosylation site, might be necessary for glycosylation to occur (Haltiwanger et al. 1990). Early characterization identified prevalent “PVST” and “TTA” motifs near the site of glycosylation on O-GlcNAc-modified peptides (Vosseller et al. 2006) somewhat reminiscent of “mucin domains” for O-GalNAc modification in the secretory pathway (Perrine et al. 2009). Later work identified a degenerate consensus sequence, [TS][PT][VT][ST][RLV][ASY] based on structural evidence obtained by crystallizing OGT with synthetic peptides (Pathak et al. 2015). Additional research based on comparative sequence analysis and mutational evidence found that many OGT substrates have positively charged residues (R/K) 7-10 residues upstream of the glycosylation site that contact Asp residues in the TPR domain (Joiner et al. 2019a). Structural work performed later attempted to identify consistent secondary structures of OGT substrates and was unable to identify any consistent pattern to structure, order, or disorder of known OGT substrates (Britto-Borges and Barton 2017).

A few themes can be identified from work attempting to define a consensus sequence, including S/T and acidic residue enrichment near the modification site, and a proline residue being near the glycosylation site. However, current research has been unable to identify one consistent consensus sequence for the O-GlcNAc modification. It is very likely that no universal consensus sequence exists, but rather specific features related to amino acid sequence or structural aspects may make a substrate more likely to be O-GlcNAc modified. These consensus features may play more of a role in determining whether or not a substrate is capable of ever being O-GlcNAc modified, rather than determining the temporal and spatial selection of a specific O-GlcNAc substrate.

Substrate selection: selection by OGT’s catalytic domain

One logical suggestion of how OGT may achieve substrate selectivity is by utilizing its two domains: the TPR domain and the catalytic domain. While the TPR domain remains the more popular choice for substrate selectivity (see below), work has also been done regarding the role of the catalytic domain itself in selecting substrates. It was suggested that OGT had a unique PIP3-binding domain on its C terminus, which was capable of binding phosphoinositides, and that this interaction during insulin signaling caused OGT to modify proteins involved in insulin signaling (Yang et al. 2008). However, this binding activity has not been able to be recapitulated in future work (Lazarus et al. 2011).

One intriguing piece of evidence has found that a specific OGT interactor, p38, interacts exclusively with the catalytic domain of OGT (Cheung and Hart 2008). This interaction was found to have no effect on what proteins OGT interacts with, but induced OGT to O-GlcNAc modify the constitutive interactor neurofilament-H. To our knowledge, this is the only protein interactor that has been shown to interact only with the catalytic domain of OGT without involvement from the TPR domain.

Substrate selection: selection by OGT’s TPR domain

By far the most attractive and most well-studied hypothesis for OGT’s substrate selection mechanism is that the TPR domain of OGT is responsible for substrate binding and selection. TPRs, which occur in a variety of proteins, are known to be involved in protein–protein interaction (D’Andrea and Regan 2003). This hypothesis is particularly appealing because it consists of several layers of potential regulation even beyond simply binding to substrates. The subhypotheses (that are not mutually exclusive!) are discussed below.

Subhypothesis 1: the TPR domain directly modulates substrate interaction

Early characterization of OGT revealed that the TPR domain, despite it lacking any catalytic activity itself, was essential for OGT’s glycosylation activity. The catalytic domain of OGT alone, with no TPRs, has no catalytic activity even toward peptide substrates, and 3 TPRs are required for a peptide substrate to be glycosylated (Kreppel and Hart 1999; Lubas and Hanover 2000). Furthermore, any truncation mutations reduced OGT activity toward protein substrates. Intriguingly, biochemical assays also revealed that the TPR domain, when coexpressed with full-length OGT and a known OGT substrate, is capable of competitively inhibiting substrate glycosylation, indicating that the TPR domain is a major player in substrate interaction (Jinek et al. 2004). This work pointed strongly toward the TPR domain of OGT being responsible for global substrate binding and suggested a role for substrate specificity.

Significant structural work has been done to identify important residues and structural features in the TPR domain involved in OGT substrate selection. We will discuss this work generally here. For the reader desiring a deeper look into specific residues and mutation studies performed, we refer to the excellent review from the group of Dr. Suzanne Walker, who has pioneered much of the structural work on OGT (Joiner et al. 2019b).

Early structural work on OGT consisted of crystal structures of partial OGTs or OGT homologs. One crystal structure of the TPR domain of OGT revealed that hydrophobic residues in the TPR domain are responsible for dimerization of the TPR domain. This study also identified an “asparagine ladder” similar to that found in another TPR-containing protein, importin-α, which is responsible for peptide binding on that protein (Jinek et al. 2004). This asparagine ladder was studied in further detail years later and found to indeed be necessary for the binding of many substrates, although this interaction is with the peptide backbone rather than R-groups, so it is likely a global interaction mechanism rather than a mechanism of substrate specificity (Levine et al. 2018). Early full-length crystal structures of bacterial homologs of OGT further confirmed an essential role for the TPR domain in OGT substrate binding (Clarke et al. 2008; Martinez-Fleites et al. 2008). The first human OGT crystal structure was completed with 4.5 TPRs, along with a model for the full-length OGT (Lazarus et al. 2011). Intriguingly, this crystal structure identified the existence of a “latch” between TPRs 10 and 11 that allows the TPR domain to be highly mobile and alters the conformation of OGT upon binding a substrate. The authors suggested that positional changes of the TPR domain may play a greater role in OGT substrate selection than direct residue-determined interaction and that these positional changes could be mediated by other factors including adapter proteins (See Subhypothesis 2). It is likely that there is a synergy between this mechanism and direct substrate binding, however, since further work has continued to identify specific residues and regions of the TPR domain that are involved in direct substrate interaction. Recent work has identified an aspartate ladder in the TPR domain of OGT, which, unlike the asparagine ladder, coordinates with Thr side chains on bound substrates, indicating that its role in protein interaction will vary depending on the substrate (Joiner et al. 2019a). Mutational studies of this aspartate ladder revealed that it plays an important role in OGT specificity and selectivity.

While a number of OGT interactors have been generally identified, the most intriguing studies in regard to the question of OGT substrate selectivity are those that perform truncation mutations to identify exact regions of binding. Collectively, these studies paint a very interesting picture of OGT substrates whose binding to OGT is mediated by the TPR domain and whose interaction region is unique to that specific substrate. The majority of proteins that have been studied in this way demonstrate the necessity of the TPR domain, and usually a specific region of the TPR domain, in order to be glycosylated (Figure 1B). For RNA Pol II, the binding region necessary for it to be glycosylated is contained within the N-terminal 5.5 TPRs (Comer and Hart 2001). Another protein, OIP106 (now known as TRAK1 , Cheung et al. 2008) interacts with OGT through TPRs 2-6 (Iyer and Hart 2003). Deletion studies of OGT for the protein Tet1 found that the entire TPR domain, except TPRs 1-3, is required for Tet1 interaction with OGT (Hrit et al. 2018). This suggests that substrates can interact with OGT via several different regions of the TPR domain, with different repeats having varying necessity for interaction to occur. Intriguingly, OGT interacts with OGA through TPRs 1-6 but also requires the N-terminal amino acids prior to the first TPR to interact (Whisenhunt et al. 2006). Furthermore, asparagine residues in TPRs 10, 11, 13, 13.5 and 3-7, but not asparagine residues in TPRs 8-9 and 2, were found to be essential for OGT interaction with and glycosylation of OGA (Kositzke et al. 2021). Collectively, these studies strongly suggest that different proteins interact with OGT via specific regions of the TPR domain unique to that protein. However, a very limited number of interactors have been studied in this way, so it is necessary to do additional truncation mutations with known OGT interactors to determine which proteins use this selection mechanism and where on the OGT protein they interact.

Subhypothesis 2: partner proteins assist in targeting the TPR domain to substrates

While we have clear evidence that the TPR domain directly selects OGT substrates, this mechanism alone is likely insufficient to explain how OGT is able to select from among thousands of individual substrates. Additional modulatory effects must be in play. One answer to this problem is the suggestion that other proteins assist in targeting the TPR domain to specific substrates. Under this hypothesis, a specific protein (called a partner or adapter protein) may bind to the TPR domain of OGT, and it may or may not be functionally O-GlcNAc modified itself. This interaction then induces OGT to interact with a substrate protein that is O-GlcNAc modified to have a functional outcome. Very limited examples in the literature exist of this phenomenon. The most predominant example is OGT’s interaction with mSin3a and HDAC1 (Yang et al. 2002). In the model presented, OGT interacts with mSin3a via TPRs 1-6 and is then recruited to interact with HDAC1, an mSin3A interactor, which is O-GlcNAc modified, that promotes transcriptional silencing. For the protein Tet2, which interacts with OGT via TPRs 5-6 with contributions by TPRs 9-12, its interaction recruits OGT to modify histone proteins (Chen et al. 2013). Additionally, a more global study found that knockdown of the protein MYPT1 caused reduction in O-GlcNAc modification of several proteins (Cheung et al. 2008). This suggests that MYPT1 may be a partner protein for OGT that targets it to other proteins and induces their O-GlcNAc modification. To our knowledge, this observation has not been further studied. Additional research identifying the proteins whose modification by OGT is dependent on MYPT1, as well as the functional outcomes of these proteins losing O-GlcNAc modification, will be helpful in confirming this partner protein hypothesis and enhancing our understanding of how it occurs within the cell.

One other intriguing suggestion of an OGT partner protein comes from a study performed in Escherichia coli (Riu et al. 2008). E. coli has no natural OGT or OGT substrates. The authors of this study found that expressing OGT alongside the partner protein Sp1 induces OGT to glycosylate many bacterial proteins that are not normally substrates and that this is dependent on the TPR domain of OGT. The authors suggest that Sp1 may act as a partner protein that induces a conformational change in the TPR domain, allowing for many substrates to then interact with OGT.

Substrate selection: OGT subcellular localization is altered to affect substrate access and selection

OGT typically localizes primarily to the nucleus with some presence in the cytoplasm (Kreppel et al. 1997). It has been suggested that OGT substrate selection is influenced by its subcellular localization, which has been documented to be affected by a variety of factors. OGT contains a nuclear localization sequence, originally thought to be between the TPR and catalytic domains (Lubas et al. 1997), and later found to be three consecutive amino acids contained in the 12th TPR (Seo et al. 2016). Importin-α interacts with this “DFP” motif and induces OGT’s nuclear transport. This research also suggested that this interaction is dependent on OGT being O-GlcNAc modified at S389, which may reveal the DFP motif and allow importin-α interaction and nuclear transport. To our knowledge, no follow-up research has been performed following this finding, but it suggests that other interactions or posttranslational modifications may influence OGT localization. Further studies exploring localization, O-GlcNAc modification, and importin-α interaction may reveal if this nuclear localization mechanism is used to modulate OGT localization and substrate access.

Additionally, partner proteins (described above) may play a role in OGT subcellular localization, thus affecting its substrate access and selection. One such example was described above, in that mSin3a promotes OGT localization at gene promoters. This has also been observed with OGT’s interaction with both Tet2 and Tet3, where in both cases OGT interacts with the Tet protein and is recruited to chromatin to modulate transcription (Chen et al. 2013; Ito et al. 2013). Intriguingly, both Tet proteins are O-GlcNAc modified, but this does not seem to have any effect on their function. Finally, during DNA damage, OGT O-GlcNAc modifies the protein H2AX and is then recruited to the site of DNA damage where it is thought to restrain the DNA damage signaling to prevent its expansion (Chen and Yu 2016).

This hypothesis may also have some overlap with the contribution of posttranslational modification to OGT selection and localization (discussed further below). During cytokinesis, Chk1 phosphorylates OGT, inducing it to localize to the midbody, where O-GlcNAc vimentin and may contribute to the completion of cytokinesis in conjunction with vimentin phosphorylation (Li et al. 2017c).

Substrate selection: post-translational modifications

It has been suggested that OGT may be regulated by posttranslational modifications. OGT is known to be extensively posttranslationally modified with a variety of modifications, including O-GlcNAc, phosphorylation and acetylation (Hornbeck et al. 2015). However, very limited work has been done at this time exploring how posttranslational modification of OGT affects its substrate specificity. One published work demonstrates that OGT is phosphorylated by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) at T444, and this phosphorylation induces OGT nuclear localization (Bullen et al. 2014). Furthermore, mutation of the phosphorylated residue causes changes in the profile of global O-GlcNAc modifications, indicating that the phosphorylation modification induces alterations in OGT substrate selectivity. Additionally, one study focusing on the short isoform of OGT (sOGT) found that six O-GlcNAc sites on OGT induce alterations in sOGT substrate binding and global O-GlcNAc modifications, indicating that these sites play a role in substrate specificity for this isoform (Liu et al. 2019). Other posttranslational modifications on OGT exist (Figure 1B), and additional work is needed in this area to identify how OGT posttranslational modifications affect its activity in various cellular contexts.

Substrate selection: UDP-GlcNAc sensing

One final possible avenue for the modulation of OGT substrate selectivity is related to its nutrient sensing. It has been well-documented that O-GlcNAc levels are responsive to glucose levels in the cell given that synthesis of the donor molecule for O-GlcNAc, UDP-GlcNAc, is dependent on the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, which branches from glycolysis (Walgren et al. 2003; Marshall et al. 2004). It has also been documented in vitro that OGT is inhibited by excess amounts of free UDP, suggesting a possible feedback mechanism (Lazarus et al. 2011). Early work in an in vitro peptide glycosylation assay showed that O-GlcNAc modification of OGT substrate peptides was affected by UDP-GlcNAc levels (Kreppel and Hart 1999). However, the connection between UDP-GlcNAc levels correlating with O-GlcNAc levels and how OGT substrate selectivity is altered by UDP-GlcNAc levels has not been explored to our knowledge. Global analysis of OGT interactors under various glucose status and UDP-GlcNAc levels would help uncover whether or not UDP-GlcNAc levels play a role in OGT substrate selectivity, and if so, by what mechanisms this occurs.

Summary of possible OGT substrate selection mechanisms

The nature of OGT as the sole enzyme modifying thousands of proteins with O-GlcNAc demands that the regulation of its substrate selection be elegant and complex. Many different possible mechanisms of substrate selection have been studied for a limited number of substrates. It is essential to note that the reality of OGT substrate selection is likely an intricate combination of those described above. The substrate selection mechanism is likely to be unique for each protein or protein class and exists as a combination of global interaction mechanisms, global cellular effects (from nutrient status), specific pathways designated for that protein (involving partner proteins and OGT posttranslational modifications), and interaction features unique to that interactor (specific amino acid interactions). In order to better understand OGT substrate selection, a combination of targeted research, like studies described above, and global assays must be performed.

To the end of understanding OGT interaction on a global scale, a limited number of attempts to define the OGT interactome have been performed. Most have focused on the full-length OGT interactome, which is helpful to define what proteins interact with OGT, but cannot determine domain effects on protein–protein interaction. These include Co-IP and microarray interactomes (Deng et al. 2014; Gao et al. 2018). One OGT TPR interactome, which identified 115 OGT-TPR–interacting proteins, has been recently defined by our group demonstrating that the TPR domain of OGT can select for substrates/partners (Stephen et al. 2020).

The O-GlcNAcase

Enzyme features

The OGA is responsible for the removal of the O-GlcNAc modification added by OGT (Figure 2A). Like OGT, it is the only mammalian OGA but exists on somatic chromosome 10 (Gao et al. 2001). Also similar to OGT, it consists of two distinct domains connected by a stalk domain. The N-terminal domain is the catalytic domain containing the OGA activity, and the C-terminal domain is termed the HAT-like, or histone acetyltransferase-like, domain (Figure 2B). Early characterization of the OGA domains suggested that this C-terminal domain contained histone acetyltransferase activity (Toleman et al. 2004), but this was disproven in later studies and the function of this domain is currently unknown (Butkinaree et al. 2008; Rao et al. 2013; He et al. 2014). OGA also exists as two distinct isoforms, one being the full-length OGA and a shorter isoform nvOGA, or “nuclear variant” OGA, so termed because the full-length OGA localizes primarily to the cytoplasm and nucleolus (Gao et al. 2001; Wells et al. 2002; Zeidan et al. 2010), whereas the shorter variant localizes more dominantly to the nucleus (Comtesse et al. 2001). Like OGT, the vast majority of work on OGA has focused on the full-length isoform, and so this review will focus on this isoform as well.

Comparatively much less work has been done characterizing OGA’s mechanisms of substrate selection. What is currently known is discussed below.

Mechanisms of substrate selection

Whether or not the OGA enzyme exhibits substrate selectivity is somewhat a subject of debate. One study suggested that OGA does not significantly recognize protein structure or sequence and rather only recognizes the sugar moiety, based on biochemical data showing that the kinetic parameters for OGA are largely unaltered by different substrates, unlike OGT (Shen et al. 2012). However, later structural studies of OGA contest this claim. One structural and biochemical study performed mutations in the stalk domain of a bacterial homolog of OGA (Schimpl et al. 2010). The authors found that these mutations affected substrate sugar cleavage and did so uniquely for each substrate tested. This suggests that the stalk domain may play a role in substrate recognition and selection. Structural modeling data on human OGA further suggested that when dimerized, the stalk domain contributes to substrate interactions specifically by interacting with hydrophobic side chains of substrates (Elsen et al. 2017). Two concurrently published human OGA structures similarly identified this groove in the dimer as of potential importance to OGA substrate binding (Li et al. 2017a; Roth et al. 2017). An additional human OGA structure found that while most OGA substrates bind to the catalytic cleft in a similar conformation, additional residues outside of the catalytic pocket may allow for substrate selectivity (Li et al. 2017b). What remains unclear from this data is whether these substrate interaction mechanisms are simply mechanisms by which OGA binds to all substrates or if they also contribute to selection. It is also important to note that two of these structural studies were performed on truncation mutations of OGA lacking the HAT-like domain, and the third was performed on both domains of OGA but crystallized separately and modeled together. It is possible that the HAT-like domain also contributes to OGA substrate selection, but little is known on its potential roles in this area.

An intriguing potential mechanism for substrate recognition for OGA lies in a unique cleavage event identified early on in OGA characterization. OGA is cleaved between its two domains by the apoptosis-executor protease caspase-3, and this cleavage surprisingly has no effect on its catalytic activity (Wells et al. 2002). A later study showed that this cleavage occurs during apoptosis and results in the N- and C-terminal fragments continuing to associate, thus retaining catalytic activity (Butkinaree et al. 2008). The authors of this study suggest that the cleavage event may have an effect on OGA substrate binding and selectivity. However, additional research is necessary to determine if and to what extent caspase-3 cleavage might alter OGA substrate selectivity.

Some specific interactors of OGA have been identified that may offer insights into mechanisms of substrate selection (Figure 2B). In one structural study mentioned previously, several OGA mutations in the stalk domain eliminate OGA catalytic activity toward the glycoprotein substrates TAB1, FOXO and CREB (Schimpl et al. 2010). Additionally, different mutations in some cases have different effects on OGA activity for specific substrates, suggesting a possible differential binding mechanism for this region of OGA. Further specific substrate studies corroborate the importance of the stalk domain for OGA substrate binding. The HAT domain of OGA was found to be dispensable for its interaction with OGT, suggesting that interaction is mediated by the catalytic and/or stalk domains (Kositzke et al. 2021). One study found that OGA interacts with several substrates via amino acids 336-548 (Whisenhunt et al. 2006). These amino acids are located between the catalytic domain and stalk domain, as defined by one of the manuscripts first defining the structural characteristics of human OGA (Li et al. 2017a). These amino acids were identified as essential for OGA to interact with OGT, and the chromatin remodelers HDAC, NCor and SMRT (Whisenhunt et al. 2006). This manuscript also intriguingly identified that OGA interacts with the corepressor Sin3A, but that this interaction requires OGT to also be present. This points to a potential “partner protein”–like mechanism for OGA as well as OGT.

Another recent manuscript that identified global OGA interactors supports this hypothesis as well (Groves et al. 2017). This manuscript used the BioID approach (Roux et al. 2012) to identify OGA interactors under oxidative stress conditions and found several intriguing results with implications for our understanding of OGA substrate selection. First, the authors found that inhibiting OGA did not significantly alter the profile of proteins that were labeled as interactors with biotin. This strongly supports the notion of partner proteins for OGA, that is, proteins that interact with OGA and are not necessarily substrates themselves, but may affect OGA’s activity through a myriad of mechanisms. The authors also identified the protein FAS as an OGA interactor and found that under oxidative stress, FAS interaction with OGA reduces its global activity. A similar phenomenon was observed when OGT interacts with OGA in T cell viral infection, where the OGT interaction reduces OGA activity (Groussaud et al. 2017). This points to a potential unique mechanism for OGA regulation in which partner proteins may affect its activity globally to the end of increasing overall O-GlcNAc levels.

It is also possible that, like OGT, OGA substrate selectivity is regulated by altered localization. However, little work has been done in this area. As mentioned previously, OGA is known to localize to the cytoplasm and nucleolus (Gao et al. 2001; Wells et al. 2002; Zeidan et al. 2010), and one study demonstrated increased nucleolar localization under nucleolar stress (Zeidan et al. 2010). Additional studies are necessary to determine how OGA localization changes due to cellular state and what factors drive these localization changes. Additionally, OGA is posttranslationally modified (Figure 2B), but any role that these posttranslational modifications may play in substrate selection has yet to be elucidated. Possible mechanisms of substrate selection are summarized in Figure 2C.

Current understandings and recommendations for future study

Multiple studies have focused on the O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes since their discovery several decades ago. Much of this work has focused on the functional outcomes and disease roles that these enzymes and the modification play. However, one fundamental question still remains unanswered: How are only two enzymes capable of modulating such an abundant and finely-tuned protein modification with so many diverse roles? Most of the work in this area has focused on the transferase, OGT. Many probable and mutually inclusive hypotheses exist to explain how OGT can select substrates. Most evidence points strongly toward a significant role for the TPR domain of OGT in substrate selection, via a variety of mechanisms including direct substrate selection and/or partner protein interactions. However, other mechanisms have been identified and may play varying roles, including posttranslational modification of OGT, alterations in OGT localization and OGT nutrient sensing. OGA, to the contrary, has had comparatively much less research performed to identify how it selects substrates. Some evidence exists for selection via structural features of the OGA enzyme, and a few potential “partner proteins” have been identified. It is also possible that OGA regulation occurs uniquely on a more global scale; e.g. interacting proteins like those described above dampen its activity globally when necessary. However, many mysteries still exist regarding OGA substrate selection. One such large gap in knowledge is the function of the HAT-like domain.

Research into OGT’s substrate selection mechanism has reached a point where highly targeted studies are possible and will be beneficial. Several global interactor lists have been identified, and many specific interacting substrates have been studied as well. The next logical step is to focus on specific interactors and identify several characteristics.

1) By what mechanism does the interactor bind OGT? What domain is responsible for the interaction? Do posttranslational modifications on OGT or the interactor play a role? Is the interactor O-GlcNAc modified?

2) How does the interaction affect OGT? Is localization altered? Does the interaction induce interaction with other substrates?

3) Under what conditions does the interaction occur? What is the functional outcome of the interaction?

One challenge that will come with validating and identifying individual interactions is that by nature many OGT interactions are transient, making them difficult to identify. A combination of biochemical techniques, including truncation mutations and in vitro binding assays to determine binding regions, and in cellulo methods like Förster resonance energy transfer (Brzostowski et al. 2009) and bimolecular fluorescence complementation (Kerppola 2008) will be useful in determining where and when interactions occur in cells. Methods used to determine functional outcomes will vary with the interactor, but since OGT interacts with many proteins involved in well-studied systems (e.g. transcription, chromatin regulation, heat shock), many assays are available for this purpose.

In order to understand how OGA selects its substrates, more preliminary work is needed. Truncation studies, like those performed for OGT, to determine what regions of OGA are responsible for its interaction with known substrates will be useful. With currently available proteomic and proximity labeling technology, it may also be extremely useful to use these approaches to identify interactors of the various domains of OGA. This approach can be used to distinguish between proteins that interact with the catalytic domain, the stalk domain, or the HAT-like domain. Structural studies focusing on the HAT-like domain may also be of use to determine if this domain plays a role in substrate selection and, if not, what function, if any, it serves. Once a more unified theory of OGA substrate interaction is identified, studies for individual interactors like described above for OGT can take place. It may also be useful to determine OGA’s interaction with OGT substrates concurrently, if the cycling of the O-GlcNAc modification on a given substrate is of particular interest.

The O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes present a fascinating story of an essential protein modification that plays a role in nearly every biological process within the cell but is regulated by only two enzymes. Uncovering the complicated and elegant mechanisms for how this regulation occurs is essential to understand how these enzymes and the resulting modification interplay with multiple biological processes related to diseases that affect millions of people worldwide.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all authors of the works cited here. Although we have attempted to be thorough in our review of the literature, with thousands of papers published in the O-GlcNAc field, we may have missed a few relevant manuscripts. Any exclusion is unintentional.

Contributor Information

Hannah M Stephen, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, University of Georgia, Athens 30602, GA, USA.

Trevor M Adams, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, University of Georgia, Athens 30602, GA, USA.

Lance Wells, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, University of Georgia, Athens 30602, GA, USA.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

The W.M. Keck foundation (to L.W. Co-PI); an NICHD National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant R21HD097652 to L.W); an NICHD (grant F30 HD098828 to H.S.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Britto-Borges T, Barton GJ. 2017. A study of the structural properties of sites modified by the O -linked 6-N- acetylglucosamine transferase. PLoS One. 12:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzostowski JA, Meckel T, Hong J, Chen A, Jin T. 2009. Imaging protein-protein interactions by Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET) microscopy in live cells. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 56:19.5.1–19.5.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullen JW, Balsbaugh JL, Chanda D, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Neumann D, Hart GW. 2014. Cross-talk between two essential nutrient-sensitive enzymes O-GlcNAc Transferase (OGT) and amp-activated protein kinase (AMPK). J Biol Chem. 289:10592–10606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butkinaree C, Cheung WD, Park S, Park K, Barber M, Hart GW. 2008. Characterization of B-N-acetylglucosaminidase cleavage by caspase-3 during apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 283:23557–23566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Chen Y, Bian C, Fujiki R, Xiaochun Y. 2013. Tet2 promotes histone O-GlcNAcylation during gene transcription. Nature. 493:561–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Yu X. 2016. OGT restrains the expansion of DNA damage signaling. Nucleic Acids Res. 44:9266–9278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung WD, Hart GW. 2008. AMP-activated protein kinase and p38 MAPK activate O-GlcNAcylation of neuronal proteins during glucose deprivation. J Biol Chem. 283:13009–13020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung WD, Sakabe K, Housley MP, Dias WB, Hart GW. 2008. O-linked β-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase substrate specificity is regulated by myosin phosphatase targeting and other interacting proteins. J Biol Chem. 283:33935–33941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AJ, Hurtado-Guerrero R, Pathak S, Schüttelkopf AW, Borodkin V, Shepherd SM, Ibrahim AFM, Van Aalten DMF. 2008. Structural insights into mechanism and specificity of O-GlcNAc transferase. EMBO J. 27:2780–2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer FI, Hart GW. 2001. Reciprocity between O-GlcNAc and O-phosphate on the carboxyl terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Biochemistry. 40:7845–7852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comtesse N, Maldener E, Meese E. 2001. Identification of a nuclear variant of MGEA5, a cytoplasmic hyaluronidase and a β-A-acetylglucosaminidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 283:634–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea LD, Regan L. 2003. TPR proteins: The versatile helix. Trends Biochem Sci. 28:655–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng RP, He X, Guo SJ, Liu WF, Tao Y, Tao SC. 2014. Global identification of O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) interactors by a human proteome microarray and the construction of an OGT interactome. Proteomics. 14:1020–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsen NL, Patel SB, Ford RE, Hall DL, Hess F, Kandula H, Kornienko M, Reid J, Selnick H, Shipman JM et al. 2017. Insights into activity and inhibition from the crystal structure of human O-GlcNAcase. Nat Chem Biol. 13:613–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Yang Y, Qiu R, Zhang K, Teng X, Liu R, Wang Y. 2018. Proteomic analysis of the OGT interactome: Novel links to epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of cervical cancer. Carcinogenesis. 39:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Wells L, Comer FI, Parker GJ, Hart GW. 2001. Dynamic O-glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins: Cloning and characterization of a neutral, cytosolic β-N-acetylglucosaminidase from human brain. J Biol Chem. 276:9838–9845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groussaud D, Khair M, Tollenaere AI, Waast L, Kuo MS, Mangeney M, Martella C, Fardini Y, Coste S, Souidi M et al. 2017. Hijacking of the O-GlcNAcZYME complex by the HTLV-1 tax oncoprotein facilitates viral transcription. PLoS Pathog. 13:1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves JA, Maduka AO, O’Meally RN, Cole RN, Zachara NE. 2017. Fatty acid synthase inhibits the O-GlcNAcase during oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 292:6493–6511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltiwanger RS, Holt GD, Hart GW. 1990. Enzymatic addition of O-GlcNAc to nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. J Biol Chem. 265:2563–2568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardville S, Hart G. 2014. Nutrient regulation of Signaling, transcription, and cell physiology by O-GlcNAcylation. Cell Metab. 20:208–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart GW. 2019. Nutrient regulation of signaling and transcription. J Biol Chem. 294:2211–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Roth C, Turkenburg JP, Davies GJ. 2014. Three-dimensional structure of a Streptomyces sviceus GNAT acetyltransferase with similarity to the C-terminal domain of the human GH84 O-GlcNAcase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 70:186–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt GD, Hart GW. 1986. The subcellular distribution of terminal N-acetylglucosamine moieties. Localization of a novel protein-saccharidie linkage, O-linked GlcNAc. J Biol Chem. 261:8049–8057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbeck PV, Zhang B, Murray B, Kornhauser JM, Latham V, Skrzypek E. 2015. PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: Mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res. 43:D512–D520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrit J, Goodrich L, Li C, Wang BA, Nie J, Cui X, Martin EA, Simental E, Fernandez J, Liu MY et al. 2018. OGT binds a conserved C-terminal domain of TET1 to regulate TET1 activity and function in development. Elife. 7:1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito R, Katsura S, Shimada H, Tsuchiya H, Hada M, Okumura T, Sugawara A, Yokoyama A. 2013. TET3-OGT interaction increases the stability and the presence of OGT in chromatin. Genes Cells. 19:52–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer SPN, Hart GW. 2003. Roles of the Tetratricopeptide repeat domain in O-GlcNAc Transferase targeting and protein substrate specificity. J Biol Chem. 278:24608–24616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M, Rehwinkel J, Lazarus BD, Izaurralde E, Hanover JA, Conti E. 2004. The superhelical TPR-repeat domain of O-linked GlcNAc transferase exhibits structural similarities to importin alpha. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 11:1001–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner CM, Levine ZG, Aonbangkhen C, Woo CM, Walker S. 2019a. Aspartate residues far from the active site drive O-GlcNAc transferase substrate selection. J Am Chem Soc. 141:12974–12978. jacs.9b06061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner CM, Li H, Jiang J, Walker S. 2019b. Structural characterization of the O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes: Insights into substrate recognition and catalytic mechanisms. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 56:97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerppola TK. 2008. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analysis as a probe of protein interactions in living cells. Annu Rev Biophys. 37:465–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kositzke A, Fan D, Wang A, Li H, Worth M, Jiang J. 2021. Elucidating the protein substrate recognition of O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) toward O-GlcNAcase (OGA) using a GlcNAc electrophilic probe. Int J Biol Macromol. 169:51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreppel LK, Blomberg MA, Hart GW. 1997. Dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. J Biol Chem. 272:9308–9315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreppel LK, Hart GW. 1999. Regulation of a cytosolic and nuclear O-GlcNAc Transferase. J Biol Chem. 274:32015–32022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus MB, Nam Y, Jiang J, Sliz P, Walker S. 2011. Structure of human O-GlcNAc transferase and its complex with a peptide substrate. Nature. 469:564–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus MB, Jiang J, Gloster TM, Zandberg WF, Whitworth GE, Vocaldo DJ, Walker S. 2012. Structural snapshots of the reaction coordinate for O-GlcNAc transferase. Nat Chem Biol. 8:966–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine Z, Fan C, Melicher MS, Orman M, Benjamin T, Walker S. 2018. O-GlcNAc transferase recognizes protein substrates using an asparagine ladder in the TPR superhelix. J Am Chem Soc. 140:3510–3513 jacs.7b13546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Li H, Lu L, Jiang J. 2017a. Structures of human O-GlcNAcase and its complexes reveal a new substrate recognition mode. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 24:362–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Li H, Hu CW, Jiang J. 2017b. Structural insights into the substrate binding adaptability and specificity of human O-GlcNAcase. Nat Commun. 8:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Li X, Nai S, Geng Q, Liao J, Xu X, Li J. 2017c. Checkpoint kinase 1-induced phosphorylation of O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase regulates the intermediate filament network during cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 292:jbc.M117.811646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Li L, Ma C, Shi Y, Liu C, Xiao Z, Zhang Y, Tian F, Gao Y, Zhang J et al. 2019. O-GlcNAcylation of Thr12/Ser56 in short form O-GlcNAc transferase (sOGT) regulates its substrate selectivity. J Biol Chem. 294:16620–16633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love DC, Kochran J, Cathey RL, Shin SH, Hanover JA. 2003. Mitochondrial and nucleocytoplasmic targeting of O-linked GlcNAc transferase. J Cell Sci. 116:647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubas WA, Hanover JA. 2000. Functional expression of O -linked GlcNAc Transferase. J Biol Chem. 275:10983–10988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubas WA, Frank DW, Hanover JA, Krause M. 1997. O -linked GlcNAc Transferase is a conserved Nucleocytoplasmic protein containing Tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem. 272:9316–9324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S, Nadeau O, Yamasaki K. 2004. Dynamic actions of glucose and glucosamine on hexosamine biosynthesis in isolated adipocytes: Differential effects on glucosamine 6-phosphate, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine, and ATP levels. J Biol Chem. 279:35313–35319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Fleites C, Macauley MS, He Y, Shen DL, Vocadlo DJ, Davies GJ. 2008. Structure of an O-GlcNAc transferase homolog provides insight into intracellular glycosylation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 15:764–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak S, Alonso J, Schimpl M, Rafie K, Blair DE, Borodkin VS, Schüttelkopf AW, Albarbarawi O, van Aalten DMF. 2015. The active site of O-GlcNAc transferase imposes constraints on substrate sequence. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 22:744–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrine C, Ju T, Cummings RD, Gerken TA. 2009. Systematic determination of the peptide acceptor preferences for the human UDP-gal:Glycoprotein-α-GalNAc β3 galactosyltranferase (T-synthase). Glycobiology. 19:321–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pravata VM, Omelková M, Stavridis MP, Desbiens CM, Stephen HM, Lefeber DJ, Gecz J, Gundogdu M, Õunap K, Joss S et al. 2020. An intellectual disability syndrome with single-nucleotide variants in O-GlcNAc transferase. Eur J Hum Genet. 28:706–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao FV, Schüttelkopf AW, Dorfmueller HC, Ferenbach AT, Navratilova I, van Aalten DMF. 2013. Structure of a bacterial putative acetyltransferase defines the fold of the human O-GlcNAcase C-terminal domain. Open Biol. 3:130021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riu IH, Shin IS, Il DS. 2008. Sp1 modulates ncOGT activity to alter target recognition and enhanced thermotolerance in E. coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 372:203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth C, Chan S, Offen WA, Hemsworth GR, Willems LI, King DT, Varghese V, Britton R, Vocadlo DJ, Davies GJ. 2017. Structural and functional insight into human O-GlcNAcase. Nat Chem Biol. 13:610–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux KJ, Kim DI, Raida M, Burke B. 2012. A promiscuous biotin ligase fusion protein identifies proximal and interacting proteins in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 196:801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacoman JL, Dagda RY, Burnham-Marusich AR, Dagda RK, Berninsone PM. 2017. Mitochondrial O-GlcNAc Transferase (mOGT) regulates mitochondrial structure, function, and survival in HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 292:4499–4518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimpl M, Schüttelkopf AW, Borodkin VS, Van Aalten DMF. 2010. Human OGA binds substrates in a conserved peptide recognition groove. Biochem J. 432:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo HG, Kim HB, Kang MJ, Ryum JH, Yi EC, Cho JW. 2016. Identification of the nuclear localisation signal of O-GlcNAc transferase and its nuclear import regulation. Sci Rep. 6:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafi R, Iyer SPN, Ellies LG, O’Donnell N, Marek KW, Chui D, Hart GW, Marth JD. 2000. The O-GlcNAc transferase gene resides on the X chromosome and is essential for embryonic stem cell viability and mouse ontogeny. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 97:5735–5739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen DL, Gloster TM, Yuzwa SA, Vocadlo DJ. 2012. Insights into O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) processing and dynamics through kinetic analysis of O-GlcNAc transferase and O-GlcNAcase activity on protein substrates. J Biol Chem. 287:15395–15408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen HM, Praissman JL, Wells L. 2020. Generation of an Interactome for the Tetratricopeptide repeat domain of O-GlcNAc Transferase indicates a role for the enzyme in intellectual disability. J Proteome Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toleman C, Paterson AJ, Whisenhunt TR, Kudlow JE. 2004. Characterization of the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) domain of a bifunctional protein with activable O-GlcNAcase and HAT activities. J Biol Chem. 279:53665–53673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres CR, Hart GW. 1984. Topography and polypeptide distribution of terminal N-acetylglucosamine residues on the surfaces of intact lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 259:3308–3317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapannone R, Mariappa D, Ferenbach AT, van Aalten DMF. 2016. Nucleocytoplasmic human O-GlcNAc transferase is sufficient for O-GlcNAcylation of mitochondrial proteins. Biochem J. 473:1693–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidyanathan K, Durning S, Wells L. 2014. Functional O-GlcNAc modifications: Implications in molecular regulation and pathophysiology. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 49:140–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosseller K, Trinidad JC, Chalkley RJ, Specht CG, Thalhammer A, Lynn AJ, Snedecor JO, Guan S, Medzihradszky KF, Maltby DA et al. 2006. O-linked N-acetylglucosamine proteomics of postsynaptic density preparation using lectin weak affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 5:923–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walgren JLE, Vincent TS, Schey KL, Buse MG. 2003. High glucose and insulin promote O-GlcNAc modification of proteins, including α-tubulin. American J Physiol Endocrinol Metabol. 284:424–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells L, Gao Y, Mahoney JA, Vosseller K, Chen C, Rosen A, Hart GW, Wells L, Gao Y, Mahoney JA et al. 2002. Dynamic O-glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins: Further characterization of the Nucleocytoplasmic B-N-Acetylglucosaminidase, O-GlcNAcase. J Biol Chem. 277:1755–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisenhunt TR, Yang X, Bowe DB, Paterson AJ, Van Tine BA, Kudlow JE. 2006. Disrupting the enzyme complex regulating O-GlcNAcylation blocks signaling and development. Glycobiology. 16:551–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Zhang F, Kudlow JE. 2002. Recruitment of O -GlcNAc Transferase to promoters by Corepressor mSin3A: Coupling protein O-GlcNAcylation to transcriptional repression. Cell. 110:69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Ongusaha PP, Miles PD, Havstad JC, Zhang F, So WV, Kudlow JE, Michell RH, Olefsky JM, Field SJ et al. 2008. Phosphoinositide signalling links O-GlcNAc transferase to insulin resistance. Nature. 451:964–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan Q, Wang Z, De MA, Hart GW. 2010. O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes associate with the translational machinery and modify Core ribosomal proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 21:1922–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]