Abstract

Objective:

To describe and compare measures of maternal depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptoms before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in a Brazilian birth cohort.

Methods:

All hospital births occurring in the municipality of Rio Grande (southern Brazil) during 2019 were identified. Mothers were invited to complete a standardized questionnaire on sociodemographic and health-related characteristics. Between May and July 2020, we tried to contact all cohort mothers of singletons, living in urban areas, to answer a standardized web-based questionnaire. They completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) in both follow-ups, and the Impact of Event Scale (IES) in the online follow-up.

Results:

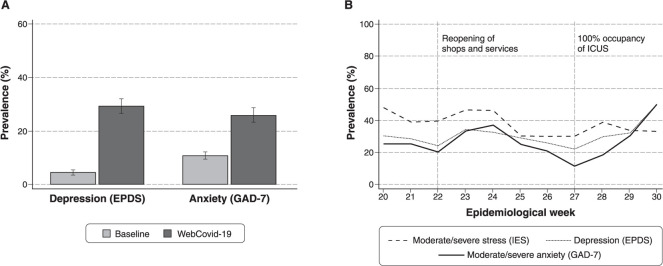

We located 1,136 eligible mothers (n=2,051). Of those, 40.5% had moderate to severe stress due to the current pandemic, 29.3% had depression, and 25.9% had GAD. Mothers reporting loss of income during the pandemic (57.2%) had the highest proportions of mental health problems. Compared to baseline, the prevalence of depression increased 5.7 fold and that of anxiety increased 2.4-fold during the pandemic (both p < 0.001).

Conclusion:

We found a high prevalence of personal distress due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, and a clear rise in both maternal depression and anxiety.

Keywords: Depression, anxiety, stress, COVID-19, mother, longitudinal study

Introduction

Studies evaluating mental health problems during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have focused on the general population and health workers.1 Few have used a longitudinal design with matched pre-pandemic information, and few have explored maternal mental health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), almost 20% of pregnant women experience a mental disorder after delivery in low and middle-income countries. This could have long-lasting effects on women and their children’s health, development, and well-being (who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/maternal-mental-health).

In southern Brazil, maternal depressive symptoms are stable during the first months after delivery, reaching an approximate prevalence of 15-16% at 12 and 24 months.2,3 However, the effect of the current COVID-19 pandemic on Brazil has been unprecedented; combined with a context in which women frequently have a higher household workload, including child care, its impact on maternal mental health could be especially severe and should be better studied.4 A recent systematic review and other original studies have suggested that there has been an increase in anxiety symptoms, but not depression. However, all these studies were conducted in upper- and middle-income countries in Europe and Asia.5,6

Thus, we aimed to describe the prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic and to compare pre- and during pandemic measures and their distribution according to sociodemographic and health-related characteristics in mothers from a Brazilian birth cohort.

Methods

The WebCovid-19 study is a web-based follow-up of the 2019 Rio Grande birth cohort. Between January 1 and December 31, 2019, all hospital births occurring in the municipality of Rio Grande, state of Rio Grande do Sul (southern Brazil), were identified and mothers were invited to answer a standardized questionnaire (online-only supplementary material). Between May 11 and July 20, 2020, we followed mothers who delivered liveborn singletons and lived in the urban area of the city at baseline (n=2,051). Potential participants were invited via phone calls, WhatsApp, or Facebook messages to answer a web-based questionnaire. We used the REDCap application to develop and manage our web-based survey.7

Mothers answered the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)8 and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale9 at baseline and the WebCovid-19 follow-up. An EPDS score ≥ 13 was defined as a positive case of probable depression, and a score ≥ 10 in the GAD-7 as a probable case of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). For the WebCovid-19 online follow-up, we included the Impact of Event Scale (IES), as validated for Brazil,10 which assesses subjective stress related to life events. A score ≥ 26 was defined as a moderate/severe stress case.

The following variables collected at baseline were used as the exposure: maternal age, self-reported skin color, maternal schooling, monthly income, and child’s sex. From the WebCovid-19 online follow-up, we used the following variables: number of people living in the household, changes in household income since the beginning of the pandemic, whether anyone in the household goes out for work, the child’s age, and whether the mother reported needing or seeking the care of a psychologist or psychiatrist in the week preceding the survey.

We estimated absolute and relative frequencies with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) and means with standard deviations (SD). Prevalence of mental health variables was calculated for the sample as a whole and according to all exposure variables and the epidemiological week in which the survey was answered. To account for differences in baseline characteristics between participants and nonparticipants and to minimize the possibility of selection bias, we used propensity scores11 to weight the results and report appropriate p-values. We used all mental-health and exposure variables collected at baseline to predict the score using logistic regression. All analyses were conducted in STATA software, version 16.1.

We obtained approval from the ethics committee of Universidade Federal do Rio Grande (protocol 15724819.6.0000.5324).

Results

We were able to contact 1,136 of all eligible women (55.4%). Of those, 1,042 completed the EPDS, 1,028 the GAD-7, and 1,064 the IES. Respondents were similar to non-respondents in terms of age, and mental health variables assessed at baseline. However, they were older and had a higher education level and income (Table S1 (261.8KB, pdf) , available as online-only supplementary material).

Mothers’ mean (SD) age was 27.5 (6.5) years at baseline (45.7% were 25 to 34 years old), and their children were, on average, 11.4 (3.7) months old at the online follow-up. Most mothers (57.2%) reported a decrease in their income since the pandemic started, 70% lived in a household with three to four residents, and four out of five mothers reported that at least one household member had had to go out to work in the preceding week.

We found that 40.5% of mothers had moderate to severe stress due to the current pandemic, 29.3% were classified as probable depression cases, and 25.9% as probable GAD cases. Compared to baseline, the prevalence of depression and anxiety was 5.7- and 2.4-fold higher (both p < 0.001; Figure 1). In contrast, only 3.7% reported needing or seeking a psychologist or psychiatrist in the preceding week (Table S1). Figure 1 also shows that all three mental health problems seemed stable during the evaluated weeks. However, a slight drop started in week 24, mainly driven by GAD. This continued until week 27, when the intensive care units (ICUs) of the city were at full capacity, at which point the prevalence of mental health problems rose again.

Figure 1. A) Comparison of baseline and online WebCovid-19 follow-ups prevalence of depression and probable generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). B) Prevalence of depression, probable GAD, and stress during epidemiological week 20 to 30 in mothers from the 2019 Rio Grande birth cohort. EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item; ICUs = intensive care units; IES = Impact of Event Scale.

As shown in Table 1, the rise in probable depression seemed higher in mothers younger than 20 or older than 35 years, those self-reporting brown skin color, those who had higher educational attainment or income, and those who lived in more crowded households. In the case of GAD, the rise seemed higher in self-reported white mothers, who had lower education or income, lived in a household with more people, and had a younger baby. The prevalence of depression and GAD during the pandemic was higher in mothers in the lowest tertile of income, those whose income decreased during the period of analysis, and those who lived in households with five people or more. Moderate/severe stress was highest among mothers older than 25 years, those who reported that at least one household member had to go out to work, and those whose household income had decreased since the beginning of the pandemic.

Table 1. Description and comparison of probable depression, probable generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and stress prevalence at baseline and at the online WebCOVID-19 pandemic follow-ups, stratified by sociodemographic and household characteristics, Rio Grande, state of Rio Grande do Sul, southern Brazil, 2019.

| Depression | GAD | Moderate/severe stress* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | WebCovid-19 | p-value† | Baseline | WebCovid-19 | p-value† | WebCovid-19 | |

| Total | 52 (5.1) | 305 (29.5) | < 0.001 | 69 (9.7) | 266 (25.9) | < 0.001 | 431 (40.6) |

| Maternal age, years | p = 0.060‡ | ||||||

| < 20 | 8 (6.9) | 40 (34.5) | < 0.001 | 12 (10.4) | 31 (27.2) | 0.002 | 36 (31.0) |

| 20-24 | 15 (5.5) | 84 (30.3) | < 0.001 | 27 (9.7) | 75 (27.6) | < 0.001 | 102 (36.8) |

| 25-34 | 23 (4.9) | 133 (27.9) | < 0.001 | 44 (9.3) | 115 (24.4) | < 0.001 | 211 (44.3) |

| 35 or older | 6 (3.5) | 48 (27.7) | < 0.001 | 17 (9.8) | 45 (26.3) | < 0.001 | 75 (43.4) |

| Skin color, self-reported | p = 0.920‡ | ||||||

| White | 37 (4.4) | 241 (28.5) | < 0.001 | 72 (8.5) | 205 (24.6) | < 0.001 | 347 (41.1) |

| Brown | 7 (5.5) | 44 (34.4) | < 0.001 | 18 (14.1) | 39 (31.5) | < 0.001 | 49 (38.3) |

| Black | 8 (11.9) | 20 (29.0) | 0.008 | 10 (14.5) | 22 (31.9) | 0.006 | 28 (40.6) |

| Educational attainment | p = 0.050‡ | ||||||

| Primary | 18 (8.6) | 63 (29.6) | < 0.001 | 17 (8.0) | 59 (28.2) | < 0.001 | 74 (34.7) |

| Secondary | 23 (4.6) | 155 (30.6) | < 0.001 | 52 (10.3) | 136 (27.3) | < 0.001 | 215 (42.4) |

| Higher | 11 (3.5) | 87 (27.0) | < 0.001 | 31 (9.7) | 71 (22.2) | < 0.001 | 135 (41.9) |

| Income tertile | p = 0.070‡ | ||||||

| 1st | 21 (7.4) | 98 (34.4) | < 0.001 | 31 (10.9) | 81 (28.8) | < 0.001 | 108 (37.9) |

| 2nd | 13 (4.3) | 87 (28.1) | < 0.001 | 27 (8.8) | 80 (26.2) | < 0.001 | 120 (38.7) |

| 3rd | 17 (4.0) | 114 (26.5) | < 0.001 | 42 (9.8) | 97 (22.8) | < 0.001 | 189 (44.0) |

| Number of people in the household during COVID-19 | p = 0.790‡ | ||||||

| < 3 | 34 (4.9) | 180 (25.8) | 0.004 | 66 (9.5) | 158 (22.9) | 0.850 | 272 (38.9) |

| 3 or 4 | 12 (6.1) | 82 (40.6) | < 0.001 | 22 (10.9) | 65 (32.7) | < 0.001 | 103 (51.0) |

| ≥ 5 | 6 (4.3) | 43 (30.5) | < 0.001 | 12 (8.5) | 43 (30.9) | < 0.001 | 49 (34.8) |

| Change in household income during COVID-19 | p = 0.029‡ | ||||||

| Increase | 1 (2.8) | 8 (22.2) | 0.084 | 0 (0.0) | 10 (28.6) | - | 13 (36.1) |

| Decrease | 39 (6.6) | 204 (34.2) | < 0.001 | 59 (9.9) | 172 (29.3) | < 0.001 | 263 (44.1) |

| Stable | 12 (3.0) | 93 (22.7) | < 0.001 | 41 (10.0) | 84 (20.7) | 0.002 | 148 (36.1) |

| Anyone in household goes out for work | p = 0.028‡ | ||||||

| Yes | 40 (4.9) | 245 (29.5) | < 0.001 | 83 (10.0) | 215 (26.2) | < 0.001 | 351 (42.2) |

| No | 12 (5.7) | 60 (28.4) | < 0.001 | 17 (8.1) | 51 (24.6) | < 0.001 | 73 (34.6) |

| Child’s sex | p = 0.870‡ | ||||||

| Male | 28 (5.4) | 157 (29.8) | < 0.001 | 44 (8.3) | 148 (28.5) | < 0.001 | 223 (42.3) |

| Female | 24 (4.7) | 148 (28.7) | < 0.001 | 56 (10.9) | 118 (23.2) | < 0.001 | 201 (39.0) |

| Child’s age (tertile), months | p = 0.280‡ | ||||||

| 1st (4.5-9.3) | 13 (3.8) | 97 (28.0) | < 0.001 | 13 (3.7) | 78 (22.7) | < 0.001 | 153 (44.1) |

| 2nd (9.4-13.6) | 16 (4.7) | 105 (30.3) | < 0.001 | 25 (7.2) | 106 (30.7) | < 0.001 | 143 (41.2) |

| 3rd (13.7-18.6) | 23 (6.8) | 103 (29.8) | < 0.001 | 62 (18.0) | 82 (24.2) | 0.290 | 128 (37.0) |

Data presented as n (%).

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Moderate/severe stress using the Impact of Event Scale (IES) was not evaluated at baseline.

p-values for mixed-effects models comparing mental health variables at baseline and the WebCovid-19 follow-up, in each category of all exposure variables, weighted using propensity score.

p-value for Wald test of proportion comparisons weighted using propensity score.

Discussion

In our sample, more than one out of four mothers had depression or anxiety, and almost half had a moderate or severe case of stress due to the current COVID-19 pandemic. There was a more than five-fold increase in probable depression prevalence and a more than two-fold increase in probable GAD. This is at least twice what would be expected in these women.2,3 All mental health problems were associated with the report of income loss since the beginning of the pandemic, but otherwise, exposure variables were associated with each of them differently, and sometimes the effects were antagonistic.

In our study, we were able to follow 55% of the original cohort and had a higher response rate among richer and better-educated mothers. Most web-based epidemiological studies report response rates around 50%. Also, most of the time the respondents are richer and more educated, as they have more internet access.12,13 We could assume that the prevalence of mental health outcomes in our follow-up was underestimated, since it is widely recognized that these mental disorders are more common among women with lower education and income.14 However, the respondents were not different from the original cohort in terms of depression and GAD measured at baseline. Furthermore, we used a propensity score to weight our analysis and minimize the possibility of bias.

Even with these limitations, this is one of the few online birth cohort follow-ups in Brazil and Latin America, and, to our knowledge, the only one that has been conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and has prospective before-and-during maternal mental health data. We used standardized procedures to measure our variables and validated scales to assess mental health outcomes. Currently, this is likely the best evidence available of maternal mental health changes in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Unlike what other studies from Europe and Asia have shown,5,6 in our sample the main driver of mental health problems was depression, not anxiety, although both increased considerably. The psychological burden of the pandemic, the isolation measures instituted in response, and its economic impact have likely worsened these women’s mental wellbeing. This is of great concern, since some may resort to harmful methods of coping, leading to an increase in gender-based intimate partner violence, less help-seeking behavior, and perhaps even increased suicidality,4 affecting not one, but at least two generations (mothers and their children). Maternal mental health problems – especially depression – adversely affect breastfeeding, mother-child bonding, and parenting quality, with detrimental impacts on the health, development, and well-being of their children and, potentially, even their future grandchildren.15

Our results could potentially indicate early signs of a mental health crisis that may be felt especially by mothers. Despite growing evidence of the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on mental health, there is still little provision for mental health care in Brazil. Ongoing monitoring of mental health in mothers and their children as this uncertain situation unfolds is essential.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the important contributions of Dr. Rebecca Pearson and Dr. Ana Luiza Soares for designing the questionnaire and comments. This study was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), grant number 433426/2018-7, and the Rio Grande Municipal Department of Health. The study was conducted within a graduate program supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES; finance code 001).

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Loret de Mola C, Martins-Silva T, Carpena MX, Del-Ponte B, Blumenberg C, Martins RC, et al. Maternal mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in the 2019 Rio Grande birth cohort. Braz J Psychiatry. 2021;43:402-406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2020-1673

References

- 1.Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113190. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacques N, Mesenburg MA, Matijasevich A, Domingues MR, Bertoldi AD, Stein A, et al. Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms from the antenatal period to 24-months postnatal follow-up: findings from the 2015 Pelotas birth cohort. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:233. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02533-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matijasevich A, Golding J, Smith GD, Santos IS, Jd Barros A, Victora CG. Differentials and income-related inequalities in maternal depression during the first two years after childbirth: birth cohort studies from Brazil and the UK. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thapa SB, Mainali A, Schwank SE, Acharya G. Maternal mental health in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:817–8. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hessami K, Romanelli C, Chiurazzi M, Cozzolino M. COVID-19 pandemic and maternal mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2020 Nov 1;:1–8. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1843155. doi: http://10.1080/14767058.2020.1843155. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwong AS, Pearson RM, Adams MJ, Northstone K, Tilling K, Smith D, et al. Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in two longitudinal UK population cohorts. Br J Psychiatry. 2020 Nov 24;:1–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.242. doi: http://10.1192/bjp.2020.242. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santos IS, Matijasevich A, Tavares BF, Barros AJ, Botelho IP, Lapolli C, et al. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in a sample of mothers from the 2004 Pelotas birth cohort study. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23:2577–88. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2007001100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sousa TV, Viveiros V, Chai MV, Vicente FL, Jesus G, Carnot MJ, et al. Reliability and validity of the Portuguese version of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:50. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.e Silva AC, Nardi AE, Horowitz M. Versão brasileira da Impact of Event Scale (IES): tradução e adaptação transcultural. Rev Psiquiatr Rio Gd Sul. 2010;32:86–93. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blumenberg C, Barros AJ. Response rate differences between web and alternative data collection methods for public health research: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Public Health. 2018;63:765–73. doi: 10.1007/s00038-018-1108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blumenberg C, Menezes AM, Gonçalves H, Assunção MC, Wehrmeister FC, Barros FC, et al. The role of questionnaire length and reminders frequency on response rates to a web-based epidemiologic study: a randomised trial. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2019;22:625–35. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elovainio M, Pulkki-Raback L, Jokela M, Kivimaki M, Hintsanen M, Hintsa T, et al. Socioeconomic status and the development of depressive symptoms from childhood to adulthood: a longitudinal analysis across 27 years of follow-up in the Young Finns study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:923–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearson RM, Culpin I, De Mola CL, Matijasevich A, Santos IS, Horta BL, et al. Grandmothers’ mental health is associated with grandchildren’s emotional and behavioral development: a three-generation prospective study in Brazil. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:184. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2166-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]