Abstract

"Testing Tele-Savvy” was a 3-arm randomized trial that recruited participants from four NIA funded Alzheimer's Disease Centers with Emory University serving as the coordinating center. The enrollment process involved each center providing a list of eligible caregivers to the coordinating center to consent. Initially, the site proposed to recruit primarily African American caregivers generated a significant amount of referrals to the coordinating center but a gap occurred in translating them into enrolled participants. To increase the enrollment rate, a “Handshake Protocol” was established, which included a warm handoff approach. During preset phone calls each week, the research site coordinator introduced potential participants to a culturally congruent co-investigator from the coordinating center who then completed the consent process. Within the first month of implementation, the team was 97% effective in meeting its goals. This protocol is an example of a successful, innovative approach to enrolling minority participants in multi-site clinical trials.

INTRODUCTION

Despite concerted efforts, racial and ethnic minority populations are continuously underrepresented in clinical research (Castillo-Mancilla et al., 2014; Spiker et al. 2009; Torres et al., 2015). Multiple barriers in the enrollment of underrepresented racial and ethnic individuals have been identified, including mistrust and skepticism of health systems, lack of awareness of clinical trials, poor access, language discordance, and ineffective communication (Disbrow et al., 2020; Erves et al., 2017; Perkins et al., 2019). Inadequate recruitment and enrollment of minority participants contributes fundamentally to the lack of representation of these groups in research which, in turn, limits the generalizability and applicability of clinical research and results validity and further exacerbates disparities (Erves et al., 2017). Participation of racial and ethnic minorities and underserved populations in clinical trials is a critical link between scientific innovation and improvements in healthcare delivery and health outcomes (Simon et al., 2014).

The willingness to participate in health research studies can be increased through efforts tailored to the recruitment of minority racial and ethnic groups. For instance, a diverse and multicultural team can help to build trust with participants (Fête et al., 2019). Fryer et al. (2016) stress the importance of racial concordance in research recruitment, along with the development of trust and self-reflection related to difference between researcher and participant. Additional successful strategies in the enrollment of underrepresented groups in clinical studies include engaging primary care providers, facilitating access to study sites, and providing clear information about the disease under study and eligibility criteria (Sun et al., 2017). Multi-site clinical trials face additional recruitment challenges such as unclear communication among team members at different sites and misalignment of the goals across sites (Cabral et al., 2018; Finlayson et al., 2019). Therefore, a staggering number of clinical trials fail to meet enrollment goals, which leads to delays, early trial termination, or inability to draw conclusions at trial completion due to loss of statistical power (Mahon et al., 2015).

The responsibilities of caregiving for persons living with dementia (PLwD) make it challenging to participate in research studies (Etkin et al.,2012). African American dementia caregivers provide care at a greater intensity and are more likely to be ‘sandwich generation’ caregivers in comparison to White caregivers (AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020; Fabious et al., 2020); therefore, their time to participate in research may be limited. In this paper, we present the details and results of an innovative approach, the ‘Handshake Protocol,’ used to improve enrollment of African American caregivers in a multi-site clinical trial.

METHODS

Study Design

The Tele-Savvy study has been previously described (Kovaleva et al., 2018). In brief, the Tele-Savvy study is a multi-site three-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) of an on-line version of the Savvy Caregiver program to enhance caregiving skills and knowledge and foster caregiving self-efficacy (mastery; Hepburn et al., 2005). The Tele-Savvy study sought to establish Tele-Savvy’s efficacy in: (a) mitigating the affective impact on dementia caregivers compared to caregivers in an attention control or usual care condition; and (b) enhancing caregiver mastery. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (#00092812) and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03033875). The study is targeted to informal dementia adult caregivers who provided on average at least 4 hours of assistance to a community-dwelling PLwD daily.

The recruitment goal for Tele-Savvy was to enroll 270 participants (65% White, 20% African American, 15% Latino) at a rate of three participants per month throughout the project’s duration. Participants were recruited from four NIA supported Alzheimer's Disease Centers (ADCs) across the United States with Emory University serving as the coordinating center. The collaborating study sites provided access to rural, urban, and ethnically diverse populations of dementia caregivers and the coordinating center was responsible for consenting the potentially interested participants from each site.

The Handshake Protocol

To establish trust, maintain good rapport, and increase research participation of individuals from minority racial and ethnic groups, the ‘Handshake Protocol’ was developed. This protocol was developed by a research coordinator (J.P.) from one of the collaborating study sites and a co-investigator (F.E.) from the coordinating center, who are culturally congruent with each other and the targeted African American recruitment population. The ‘Handshake Protocol’ uses a warm handoff approach that shares the responsibility between the study sites and coordinating center for enrolling research participants.

The phrase ‘warm handoff’ was originated in customer service and is often conducted in person, between two members of a health care team, in front of the patient and/or family (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2017). This approach has been used in various settings to ensure the customer or patient is connected to someone who can properly address their needs. In health care, a warm handoff approach involves: (a) one health care team member introducing another team member to the patient; (b) explaining why the other team member can better address a specific issue with the patient; and (c) emphasizing the other team member’s competence (Schottenfeld et al., 2016).

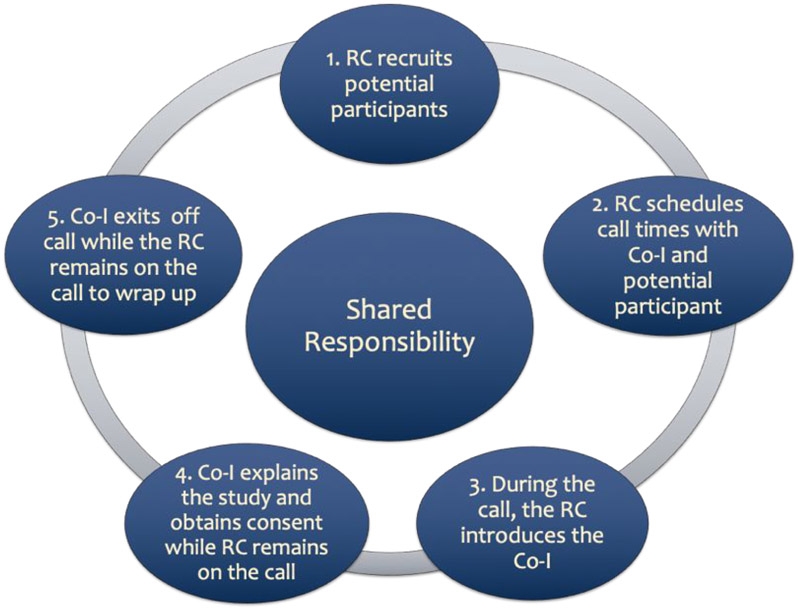

In alignment with the original warm handoff approach, the ‘Handshake Protocol’ involved pre-scheduled phone calls with the co-investigator, site coordinator, and prospective participants based on co-investigators’ availability; this availability was provided monthly to the site’s research coordinator. Reminder notifications (phone calls or emails) were sent out a week before the scheduled call. On the day of the consent call, the research coordinator called and checked in with the potential participant and then patched the co-investigator into the call who then explained the study and engaged the participants in the informed consent process. Once verbal consent was obtained, the co-investigator addressed any immediate concerns the participant might have had and then exited the call. The coordinator then addressed any additional concerns with the participant and offered his/her availability if any further questions may arise. Figure 1 outlines the steps for the protocol.

Figure 1. ‘Handshake Protocol’ Process.

RC = Research Coordinator, Co-I = Co-Investigator

ENROLLMENT OUTCOMES

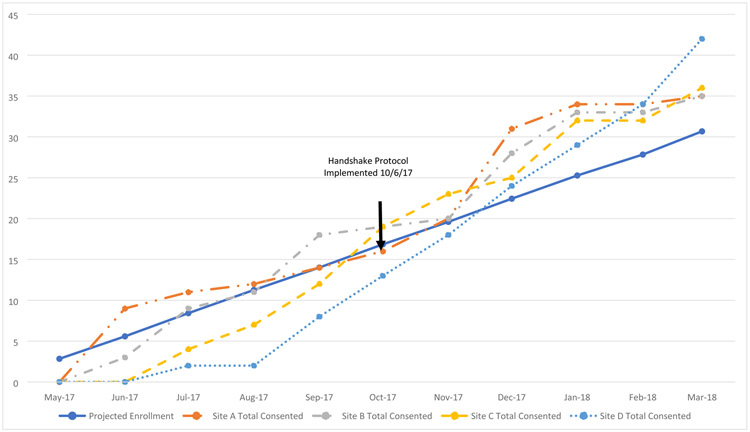

Part-time study coordinators from the Outreach, Recruitment, and Education cores of each ADC were responsible for enrolling a total of 75 caregivers at each site. The initial enrollment plan included for each study site to advertise the study and refer potentially eligible participants to the coordinating center for consenting. In the first five months of the study, three study sites (A, B, C) met and exceeded their target for enrollment (Figure 2). However Site D, proposed to recruit primarily African American participants, generated a significant amount of referrals to the coordinating center but a gap occurred in translating them into enrolled participants.

Figure 2.

Overall Study Enrollment (All Racial Groups)

To increase enrollment of African American participants into the study, the ‘Handshake Protocol’ was implemented in October 2017. The first month after the implementation of the ‘Handshake Protocol’, the team was at 92% of projected enrollment and at 107% by the second month (Table 1). Within two months, the team was able to close the enrollment gap among the study sites and exceeded its target enrollment (Figure 2). Enrollment continued to increase after meeting monthly projections. From October 2017 through March 2018, enrollment of referred participants from Site D increased by 525% (n = 42). This growth was significant and comparable to the enrollment from the other sites: Site A (250%, n = 21), Site B (194%, n = 17), and Site C (300%, n = 24).

Table 1.

Overall Site Enrollment and Performance (All Racial Groups)

| Site A | Site B | Site C | Site D | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment Months |

Consents per month |

Performance | Consents per month |

Performance | Consents per month |

Performance | Consents per month |

Performance |

| May-2017 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Jun-2017 | 9 | 161% | 3 | 54% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Jul-2017 | 3 | 131% | 6 | 107% | 4 | 47% | 2 | 24% |

| Aug-2017 | 1 | 107% | 2 | 98% | 3 | 62% | 0 | 18% |

| Sep-2017 | 2 | 100% | 7 | 128% | 5 | 86% | 6 | 57% |

| Oct-2017 | 2 | 95% | 1 | 113% | 7 | 113% | 5 | 77% |

| Nov-2017 | 4 | 102% | 1 | 102% | 4 | 117% | 5 | 92% |

| Dec-2017 | 11 | 138% | 8 | 125% | 2 | 111% | 6 | 107% |

| Jan-2018 | 3 | 135% | 5 | 131% | 7 | 127% | 5 | 115% |

| Feb-2018 | 0 | 122% | 0 | 119% | 0 | 115% | 5 | 122% |

| Mar-2018 | 1 | 114% | 2 | 114% | 4 | 117% | 8 | 137% |

The ‘Handshake Protocol” was maintained throughout the study and Site D consented 86 participants over the course of the study recruitment period (22 months). Overall, study enrollment exceeded targeted goals (N = 311) with 21% (n = 65) African American participants. Latino caregivers comprised 4% (n =13) of the overall study enrollment which was primarily recruited from Sites A, B, and C (n = 10). The collaboration between Site D and the coordinating center using the ‘Handshake Protocol’ resulted in the enrollment of majority of the African American study participants (55%, n = 36).

DISCUSSION

Recruitment and enrollment are two significant barriers in research, particularly for historically underrepresented groups, including racial and ethnic minorities. The lack of representation of these groups in research limits the generalizability and applicability of clinical research and results (Simon et al., 2014). Successful recruitment and enrollment methods for underrepresented populations include the essential components of having effective communication tools, direct benefits for participants, racial concordance, community partnerships, and stakeholders involved in the research process (Fête et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2019; McDougall et al., 2015; Torres et al., 2015). This paper reported on the ‘Handshake Protocol,’ a successful and comprehensive enrollment approach used in a multi-site RCT to improve enrollment of African American caregivers. We believe one strength of this handoff was the racial concordance between the research personnel completing the consenting process at both sites and the targeted potential research participants. While we acknowledge that research team racial/ethnic concordance may not always be feasible, we encourage principal investigators to assemble diverse teams. A diverse team is important for building trust and becoming more engaged with racial and ethnic minority communities (Fête et al., 2019).

Our experience demonstrates the importance of creative efforts by the research team to build relationships with and show humility, honesty, and respect to the research participant (Fryer et al., 2016). In the case of the ‘Handshake Protocol,’ the active role the research site coordinator in building relationships with local caregivers during recruitment cannot be overemphasized. Relationship building and interpersonal skills of the research team is as critical as racial/ethnic concordance in producing good enrollment outcomes (Fryer et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2019). The research team should aim to possess a high degree of social intelligence, understand and appreciate historical context, and demonstrate an ability to utilize other qualities, such as empathy, trustworthiness, and commitment to genuinely support relationship building (Fryer et al., 2016). We were strategic in maintaining the trust established between the research site coordinator and caregiver by engaging the coordinator in the entire consenting process. Ongoing communication (i.e., emails and phone calls) between the research coordinator at Site D and the co-investigator from coordinating center likely also contributed to successful enrollment of participants.

Implementing the ‘Handshake Protocol’ resulted in improved consent rates for the study and contributed to the achievement of planned enrollment of African American caregivers in the study. Specifically, the collaboration between Site D and the coordinating center resulted in greater than 500% increase in enrollment. Site D’s focus on enrolling minority caregivers also appeared to be successful as this was the site from which most African Americans were recruited. These outcomes are encouraging because they affirm the importance of deploying comprehensive enrollment strategies to address the disparity in research participation among minorities. Researchers can benefit from broadening their current recruitment and enrollment strategies by developing or using innovative strategies like the ‘Handshake Protocol’ to enroll participants into research studies.

Challenges and Limitations

While the warm handoff approach adopted for the ‘Handshake Protocol’ was an effective and successful enrollment strategy, it is time consuming upfront. In this study, not all the participants who consented were assigned to a cohort due to caregivers’ conflicting schedules and changes in the status or living arrangements of the family members under their care. Also, there was only one co-investigator at the coordinating center who participated in the consent process using the ‘Handshake Protocol” with Site D; therefore, implementation of this strategy was constrained to the investigator’s schedule. Additionally, the ‘Handshake Protocol’ was not applied in this study to support the recruitment of Latino caregivers and further work is necessary to modify the approach for success with this particular ethnic group.

Conclusion

For multi-site clinical trials, enrollment strategies may vary at each site but the overall goal is to promote successful study participation (Santos et al., 2017). Researching within populations which do not readily participate in research can be challenging, but this challenge can be mitigated by incorporating strategies like the ‘Handshake Protocol.’ When implemented, such strategies may help increase trial participation among underrepresented populations. Strategies shared in this paper will assist researchers in identifying and addressing challenges related to enrollment of diverse groups of participants into clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the Tele-Savvy research team and would like to acknowledge the research coordinators at each study site for their assistance in recruitment.

FUNDING

This multi-site clinical trial is funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), a division of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), under Award Number R01 AG054079 (K.H.). The National Institute on Aging also funded the Alzheimer's Disease Centers that participated in this trial: 2P50 AG025688, Emory University; P30 AG101061, Rush University; P30 AG13854, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine; P30 AG008017, Oregon Health & Science University. The authors would also like to acknowledge this work resulted from the development plan and activities of the primary author's career development award through NIA (K23AG065452). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

CONFLICT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS APPROVAL

Research was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB Approval # 00092812).

Contributor Information

Fayron Epps, Emory University, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing.

Glenna Brewster, Emory University, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing.

Judy S. Phillips, Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Rush University Medical Center

Rachel Nash, Emory University, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing.

Raj C. Shah, Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Rush University Medical Center

Kenneth Hepburn, Emory University, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2017). Warm handoff. Retrieved from https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/reports/engage/interventions/handoff-slides.html

- Cabral HJ, Davis-Plourde K, Sarango M, Fox J, Palmisano J, & Rajabiun S (2018). Peer support and the HIV continuum of care: Results from a multi-site randomized clinical trial in three urban clinics in the United States. AIDS and Behavior, 22(8), 2627–2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Mancilla JR, Cohn SE, Krishnan S, Cespedes M, Floris-Moore M, Schulte G, Pavlov G, Mildvan D, & Smith KY (2014). The AUPSG: minorities remain under represented in HIV/AIDS research despite access to clinical trials. HIV Clinical Trials, 15(1):14–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disbrow EA, Arnold CL, Glassy N, Tilly CM, Langdon KM, Gungor D, & Davis TC (2020, online). Alzheimer disease and related dementia resources: Perspectives of African American and Caucasian family caregivers in northwest Louisiana. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 10.1177/0733464820904568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erves JC, Mayo-Gamble TL, Malin-Fair A, Boyer A, Joosten Y, Vaughn YC, Sherden L, Luther P, Miller S, & Wilkins CH (2017). Needs, priorities, and recommendations for engaging underrepresented populations in clinical research: A community perspective. Journal of Community Health, 42(3), 472–480. 10.1007/s10900-016-0279-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin CD, Farran CJ, Barnes LL, Shah RC (2012). Recruitment and enrollment of caregivers for a lifestyle physical activity clinical trial. Research in Nursing Health.2012;35(1):70–81. 10.1002/nur.20466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabius CD, Wolff JL, & Kasper JD (2020). Race Differences in Characteristics and Experiences of Black and White Caregivers of Older Americans. Gerontologist, 60, 1244–1253. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fête M, Aho J, Benoit M, Cloos P, & Ridde V (2019). Barriers and recruitment strategies for precarious status migrants in Montreal, Canada. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1). 10.1186/s12874-019-0683-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer CS, Passmore SR, Maietta RC, Petruzzelli J, Casper E, Brown NA, Butler J, Garza MA, Thomas SB, & Quinn SC (2016). The symbolic value and limitations of racial concordance in minority research engagement. Qualitative Health Research, 26(6), 830–841. 10.1177/1049732315575708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson M, Akbar N, Turpin K, & Smyth P (2019). A multi-site, randomized controlled trial of MS INFoRm, a fatigue self-management website for persons with multiple sclerosis: Rationale and study protocol. BMC Neurology, 19(1), 142. 10.1186/s12883-019-1367-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn K, Lewis M, Narayan S, Center B, Tornatore J, Bremer KL, & Kirk LN (2005). Partners in caregiving: A psychoeducation program affecting dementia family caregivers' distress and caregiver outlook. Clinical Gerontologist, 29 ,53–69. 10.1300/J018v29n01_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Vore DD, Chirinos C, Wolf J, Low D, Willard-Grace R, Tsao s., Garvey C, Donesky D, Su G, & Thom DH (2019). Strategies for recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for a clinical trial. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1). 10.1186/s12874-019-0679-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovaleva M, Bilsborough E, Griffiths P, Nocera J, Higgins M, Epps F, Kilgore K, Lindauer A, Morhardt D, Shah R, Hepburn K (2018). Testing Tele-Savvy: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Research in Nursing and Health, 41(2), 107–120. 10.1002/nur.21859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall G, Simpson G, & Friend M (2015). Strategies for research recruitment and retention of older adults of racial and ethnic minorities. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 41(5), 14–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon E, Roberts J, Furlong P, Uhlenbrauck G, & Bull J (2015). Barriers to clinical trial recruitment and possible solutions: A stakeholder survey. Applied Clinical Trials. Retrieved from http://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/barriers-clinical-trial-recruitment-and-possible-solutions-stakeholder-survey?pageID=1 [Google Scholar]

- AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving. (2020). Caregiving in the United States 2020. Washington, DC: AARP. Retrieved from 10.26419/ppi.00103.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Hart A, Dillard RL, Wincek RC, Jones DE, & Hackney ME (2019). A formative qualitative evaluation to inform implementation of a research participation enhancement and advocacy training program for diverse Seniors: The DREAMS program. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 38(7), 959–982. 10.1177/0733464817735395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos CE, Kornienko O, & Rivas-Drake D (2017). Peer influence on ethic-racial identity development: A multi-site investigation. Child Development 88(3), 725–742. 10.1111/cdev.12789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schottenfeld L, Petersen D, Peikes D, Ricciardi R, Burak H, McNellis R, & Genevro J (2016). Creating Patient-centered Team-based Primary Care. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 16-0002-EF. Retrieved from https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/creating-patient-centered-team-basedprimary-care [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Gilbert L, Ciampi A, & Basso O (2017). Recruitment challenges in clinical research: Survey of potential participants in a diagnostic study of ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology, 146(3), 470–476. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiker CA, & Weinberg AD (2009). Policies to address disparities in clinical trials: The EDICT project. Journal of Cancer Education, 24(S2). 10.1007/BF03182311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MA, de la Riva EE, Bergan R, Norbeck C, McKoy JM, Kulesza P, Dong X, Schink J, & Fleisher L (2014). Improving diversity in cancer research trials: the story of the Cancer Disparities Research Network. Journal of Cancer Education: The Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Education, 29(2), 366–374. 10.1007/s13187-014-0617-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres S, de la Riva EE, Tom LS, Clayman ML, Taylor C, Dong X, & Simon MA (2015). The development of a communication tool to facilitate the cancer trial recruitment process and increase research literacy among underrepresented populations. Journal of Cancer Education, 30(4), 792–798. 10.1007/s13187-015-0818-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]