Abstract

Hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI has emerged as a novel means to evaluate pulmonary function via 3D mapping of ventilation, interstitial barrier uptake, and RBC transfer. However, the physiological interpretation of these measurements has yet to be firmly established. Here, we propose a model that uses the three components of 129Xe gas-exchange MRI to estimate accessible alveolar volume (VA), membrane conductance, and capillary blood volume contributions to DLCO. 129Xe ventilated volume (VV) was related to VA by a scaling factor kV = 1.47 with 95% confidence interval [1.42, 1.52], relative 129Xe barrier uptake (normalized by the healthy reference value) was used to estimate the membrane-specific conductance coefficient kB = 10.6 [8.6, 13.6] mL/min/mmHg/L, whereas normalized RBC transfer was used to calculate the capillary blood volume-specific conductance coefficient kR = 13.6 [11.4, 16.7] mL/min/mmHg/L. In this way, the barrier and RBC transfer per unit volume determined the transfer coefficient KCO, which was then multiplied by image-estimated VA to obtain DLCO. The model was built on a cohort of 41 healthy subjects and 101 patients with pulmonary disorders. The resulting 129Xe-derived DLCO correlated strongly (R2 = 0.75, P < 0.001) with the measured values, a finding that was preserved within each individual disease cohort. The ability to use 129Xe MRI measures of ventilation, barrier uptake, and RBC transfer to estimate each of the underlying constituents of DLCO clarifies the interpretation of these images while enabling their use to monitor these aspects of gas exchange independently and regionally.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is perhaps one of the most comprehensive physiological measures used in pulmonary medicine. Here, we spatially resolve and estimate its key components—accessible alveolar volume, membrane, and capillary blood volume conductances—using hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI of ventilation, interstitial barrier uptake, and red blood cell transfer. This image-derived DLCO correlates strongly with measured values in 142 subjects with a broad range of pulmonary disorders.

Keywords: aging effect, diffusing capacity, DLCO, KCO, 129Xe gas-exchange MRI

INTRODUCTION

Hyperpolarized (HP) 129Xe MRI has biophysical properties that make it uniquely suited to image ventilation and pulmonary gas exchange (1). After inhalation, 129Xe freely diffuses from the airspaces through alveolar-capillary barrier comprised of alveolar epithelial cells, interstitial tissues, and capillary endothelial cells, and subsequently into the red blood cells (RBCs) (2). Notably, 129Xe exhibits distinct magnetic resonance (MR) frequency shifts in the airspace, barrier, and RBCs (3), allowing separate imaging of its distribution in all three compartments. Thus, a single inhalation of 129Xe permits 3D imaging of 129Xe ventilation, its uptake in interstitial barrier tissues, and its transfer to RBCs (4, 5). Such imaging has been used to spatially characterize disease burden across a range of pulmonary disorders. In patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), 129Xe MRI was characterized by elevated barrier uptake coupled with reduced RBC transfer (6). This combination of 129Xe image features was recently proposed as a potential prognostic marker for IPF progression (7). These imaging features have also been reported in preliminary studies of patients with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) (8), while reduced RBC transfer is also prevalent in pre- and postcapillary pulmonary hypertension (PH) (9). In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), defects are commonly seen in all three compartments (10).

While 129Xe gas-exchange MRI has demonstrated unique signatures across a wide range of conditions (9), the physiological interpretation of these measures of regional barrier uptake and RBC transfer remains to be firmly established. It is therefore necessary to connect the features of 129Xe MRI to established clinical metrics in order for it to help better understand patients’ symptoms and guide their care. To this end, perhaps the most comprehensive physiological measurement available to pulmonary medicine is the diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), which is affected by accessible alveolar volume, membrane conductance, and capillary blood volume conductance (11). It is therefore encouraging that DLCO was found to correlate strongly with the 129Xe-derived ratio of RBC transfer to barrier uptake in patients with IPF (6, 12). It is thought that the reduced RBC/barrier ratio is attributable to thickening of the interstitial tissues, which increases 129Xe uptake in the barrier compartment while slowing its diffusive transfer to RBCs (6). However, despite early proposals to use such spectroscopic metrics to estimate membrane and capillary conductance contributions to DLCO in rats, the RBC/barrier ratio does not yet have a physiological interpretation (13). Specifically, the RBC/barrier ratio cannot account for DLCO contributions such as accessible alveolar volume (VA) (14), or emphysematous loss of membrane conductance (15), nor does it spatially resolve these components. Current methods to deconvolve the membrane and capillary blood volume constituents of DLCO require either cumbersome multiple breaths of different O2 concentrations (16) or dual measures of CO and NO diffusing capacity (17, 18), neither of which are routinely performed in clinical practice. Alternatively, these components can be both separated and spatially resolved in a single inhalation using 129Xe gas-exchange MRI. We recently proposed a relationship between 129Xe and DLCO that employs the images of all three 129Xe MRI compartments (9). In that study, 129Xe barrier uptake (or its reciprocal) was used to estimate membrane conductance, whereas 129Xe RBC transfer provided blood volume conductance. However, it was limited by a relatively small sample and has not been rigorously tested for validity across different disease groups.

Here, we seek to establish a generalized model that permits using 129Xe MRI to elucidate and spatially resolve the key constituents of gas exchange measured by single breath DLCO. We hypothesize that features of 129Xe MRI can be used to estimate accessible alveolar volume and the conductances attributable to the membrane and capillary blood volume in the framework of Roughton and Forster (11). This approach estimates the 129Xe barrier uptake and RBC transfer relative to a healthy reference cohort and converts them to specific conductance using scaling coefficients derived from the entire study population. We demonstrate that this approach can be used to discern the underlying contributions to a patient’s DLCO and transfer coefficient KCO. This combined approach not only provides a means to separate and image the individual components of this well-known gas exchange metric but also provides a framework to interpret 129Xe MRI in the context of established physiological principles.

METHODS

Subject Recruitment and DLCO Measurements

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Duke University Medical Center and recruited a cohort of 41 healthy volunteers and 101 patients (who provided written informed consent) with a broad range of obstructive, restrictive, and pulmonary-vascular disorders. The patient cohort included 21 COPD, 12 IPF, 27 NSIP, 31 precapillary PH (Pre-PH, including pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension) and 10 postcapillary PH (Post-PH). The healthy volunteers had no smoking history or known respiratory conditions. All subjects underwent 129Xe gas-exchange MRI and pulmonary function testing (PFT) within 3 mo of MRI. Subject demographics and PFT results are summarized in Table 1. Note that 59 of these subjects (23 healthy volunteers, 8 COPD, 12 IPF, 10 Pre-PH, and 6 Post-PH patients) had been included in prior manuscripts that used 129Xe MRI to establish disease signatures and quantification methods (4–6, 9).

Table 1.

Subject demographics and PFT results

| Characteristic | Healthy | COPD | IPF | NSIP | Pre-PH | Post-PH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 41 | 21 | 12 | 27 | 31 | 10 |

| Age, yr | 39 ± 17 (19, 70) | 66 ± 11 (23, 75) | 68 ± 6 (56, 79) | 57 ± 9 (37, 71) | 55 ± 13 (21, 77) | 69 ± 13 (30, 74) |

| Female | 13 (32%) | 11 (52%) | 2 (17%) | 20 (74%) | 17 (55%) | 3 (30%) |

| Nonwhite race | 18 (44%) | 4 (19%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (44%) | 6 (19%) | 2 (20%) |

| PFT* FEV1, % predicted FVC, % predicted FEV1/FVC, % predicted TLC, % predicted DLCO, mL/min/mmHg DLCO, % predicted VA, L KCO, mL/min/mmHg/L |

96 ± 18 (51, 135) 97 ± 18 (47, 128) 100 ± 10 (81, 132) 101 ± 15 (70, 130) 26 ± 6 (15, 37) 97 ± 16 (53, 125) 5.4 ± 1.2 (3.1, 7.7) 4.9 ± 0.8 (3.4, 6.7) |

54 ± 18 (24, 88) 88 ± 21 (48, 133) 60 ± 15 (36, 79) 104 ± 15 (84, 133), n = 16 13 ± 5 (5, 20) 56 ± 19 (28, 95) 4.3 ± 1.0 (1.6, 5.4) 3.1 ± 1.3 (1.4, 6.4) |

71 ± 19 (38, 109) 66 ± 20 (30, 105) 110 ± 7 (95, 124) 51 ± 10 (43, 63), n = 3 12 ± 3 (7, 17) 48 ± 12 (27, 68) 3.4 ± 0.9 (2.0, 5.2) 3.4 ± 0.6 (2.7, 4.3) |

66 ± 15 (47, 97) 64 ± 14 (44, 92) 103 ± 7 (89, 116) 58 ± 11 (45, 70), n = 5 13 ± 6 (5, 26) 56 ± 18 (23, 89) 2.9 ± 1.0 (1.5, 5.4) 4.3 ± 0.9 (2.3, 5.8) |

71 ± 21 (22, 112) 79 ± 18 (44, 115) 88 ± 16 (34, 116) 87 ± 21 (43, 139), n = 27 15 ± 8 (5, 35) 61 ± 25 (20, 119) 4.3 ± 1.5 (2.4, 7.4) 3.4 ± 1.3 (0.2, 6.3) |

74 ± 19 (53, 100) 78 ± 23 (52, 115) 97 ± 11 (84, 119) 87 ± 27 (57, 119), n = 8 19 ± 7 (6, 31) 76 ± 24 (28, 106) 4.6 ± 1.7 (2.2, 7.2) 4.3 ± 1.4 (2.4, 7.1) |

Continuous variables presented as means ± SD (minimum, maximum); categorical variables presented as frequency (proportion). COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; PFT, pulmonary function testing; Pre-PH, pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension; Post-PH, postcapillary pulmonary hypertension; TLC, total lung capacity.

Most recent available clinical values presented. PFTs were performed within 6 mo of MRI for all subjects. GLI reference was used to calculate percentage predicted FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC ratio (19) and percentage predicted DLCO (20). Percentage predicted TLC was calculated using Crapo/Hsu reference values.

DLCO was measured clinically for patients and as part of the research study for healthy volunteers, both according to the ATS/ERS guidelines (21). This included obtaining at least two acceptable maneuvers that were within 2 mL/min/mmHg (0.67 mmol/min/kPa) or 10% of each other. The average of at least two acceptable maneuvers that met the repeatability requirement were reported (i.e., outliers excluded), with a maximum of four attempts.

129Xe Gas-Exchange Image Acquisition and Quantification

129Xe gas-exchange MRI was performed on either a 1.5 T (GE 15M4 EXCITE) or a 3-T (SIEMENS MAGNETOM Trio) scanner. For each subject, an interleaved radial acquisition of gas- and dissolved-phase signal was performed during a 15-s breath-hold (22). The signal was acquired at an echo time (TE90, ∼0.98 ms at 1.5 T, ∼0.48 ms at 3 T) at which the dissolved-phase signal could be decomposed into images of the barrier and RBC compartments, using the one-point Dixon method(1). At both field strengths, imaging used the same effective TR of 15 ms and flip angles (∼0.5° for gas-phase and ∼20° for dissolved-phase) to ensure identical gas exchange contrast. The sampling dwell time for each radial ray was 64 µs at 1.5 T and 19.6 µs or 9.8 µs for 3 T imaging. This generated 3D images of the gas, barrier, and RBC compartments that were reconstructed into 6-mm isotropic voxels (23). A 1H MRI with the same voxel resolution and lung inflation state was acquired for each subject immediately after the 129Xe scan to provide the structural reference of the thoracic cavity (5).

The images of the three compartments were quantified as described previously (5). First, the 1H MRI scan was segmented to delineate the thoracic cavity, excluding major airways and blood vessels. The thoracic cavity mask was then registered to the 129Xe MRI using a rigid transformation within the ANTS package (nonrigid registration was applied in three subjects who had substantial lung volume difference between the two breath-holds) (24). The gas-phase 129Xe image was normalized by its top percentile and cast into six bins based on distributions derived from a healthy reference cohort. The six bins centered on the mean signal intensity of the reference distribution, the standard deviation of which defined the width of each bin. The lowest bin was considered to contain the ventilation defects. The 29Xe-ventilated volume was then calculated using the thoracic cavity volume, derived from the 1H MRI scan, minus the ventilation defect volume. The 3D images of 129Xe in barrier and RBC were normalized by the gas-phase image on a voxel-by-voxel basis, creating barrier–gas, and RBC-gas ratio maps, which were also converted into binning maps using thresholds derived from healthy reference cohorts established at both field strengths and all acquisition bandwidths (25). These are referred to as barrier tissue uptake and RBC transfer maps, and their mean values relative to those of the reference cohort were used to characterize individual subjects.

Estimating DLCO and KCO from 129Xe Gas-Exchange MRI Features

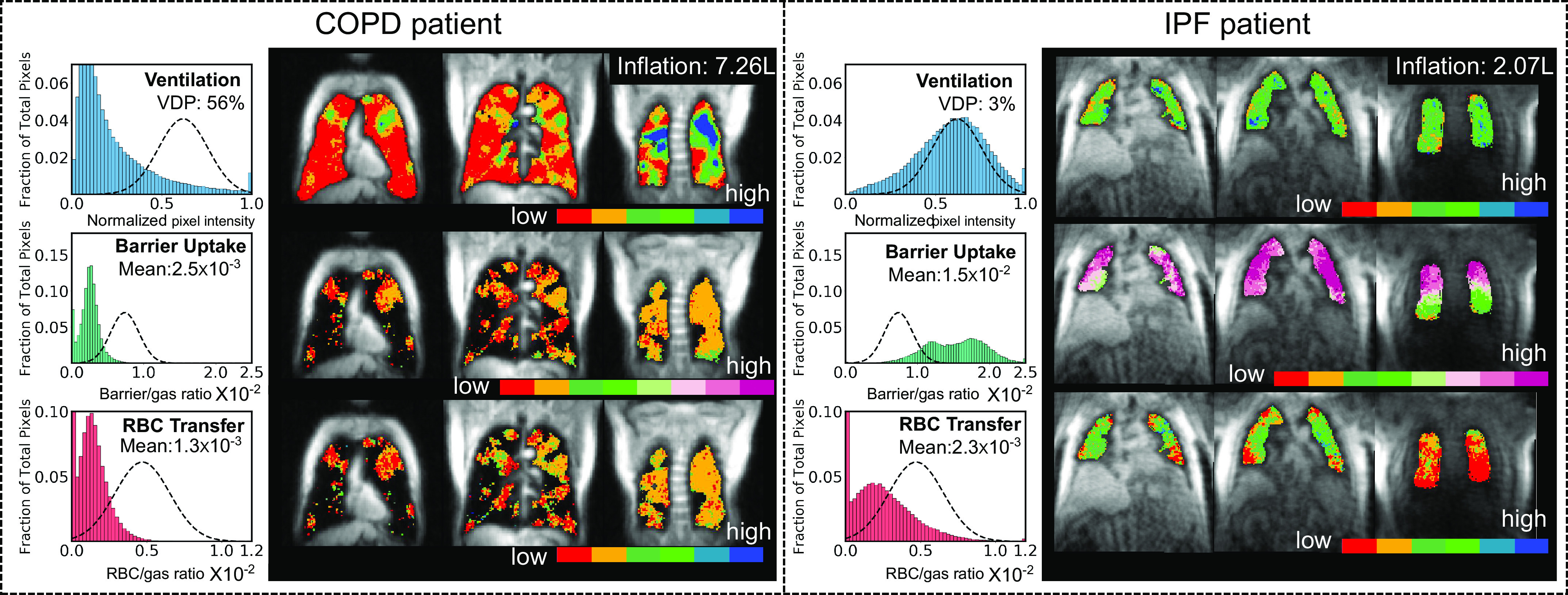

Representative 129Xe gas-exchange images and the derived metrics are shown in Fig. 1 for a patient with COPD and a patient with IPF. 129Xe MRI features of lung inflation volume, ventilation defect percentage (VDP), mean barrier uptake (normalized by the healthy reference value), and similarly normalized mean RBC transfer were used to estimate KCO and DLCO using the framework of Roughton and Forster (11). This approach considers diffusing capacity to be determined by two serially ordered conductances: one attributable to the membrane DM and one attributable to capillary blood volume θVc; here, θ is the reaction rate of CO with RBCs and Vc is the capillary blood volume.

Figure 1.

Example 129Xe gas-exchange images and metrics of a patient with COPD (left) and patient with IPF (right). For each patient, the histograms on the left show the distribution of voxel intensities. The x-axis of each histogram shows the normalized pixel intensities within the lungs for that particular contrast. For ventilation, this is the rescaled intensity (normalized to 0–1 using 99 percentile). For barrier and RBC, it is the ratio of signal intensity to the corresponding gas-phase signal in that pixel. The dashed lines represent healthy reference distributions. The images on the right show slices of each of the three 129Xe color maps. The images have isotropic resolution, and the slices are coronal slices shown from left to right, reflecting an anterior to posterior (ventral to dorsal) progression. 129Xe MRI-derived lung inflation volume, ventilation defect percentage (VDP), mean barrier uptake, and mean RBC transfer are used to estimate the key constituents of DLCO. VDP (shown in red on the images) refers to the ventilation defect percentage, reflecting those pixels within the thoracic cavity with a signal intensity more than 2 SD below the healthy reference mean. Mean barrier uptake and RBC transfer were calculated by taking the mean of voxel intensities in the thoracic cavity (5). COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

| (1) |

DLCO is the product of the transfer coefficient KCO and the accessible alveolar volume VA:

| (2) |

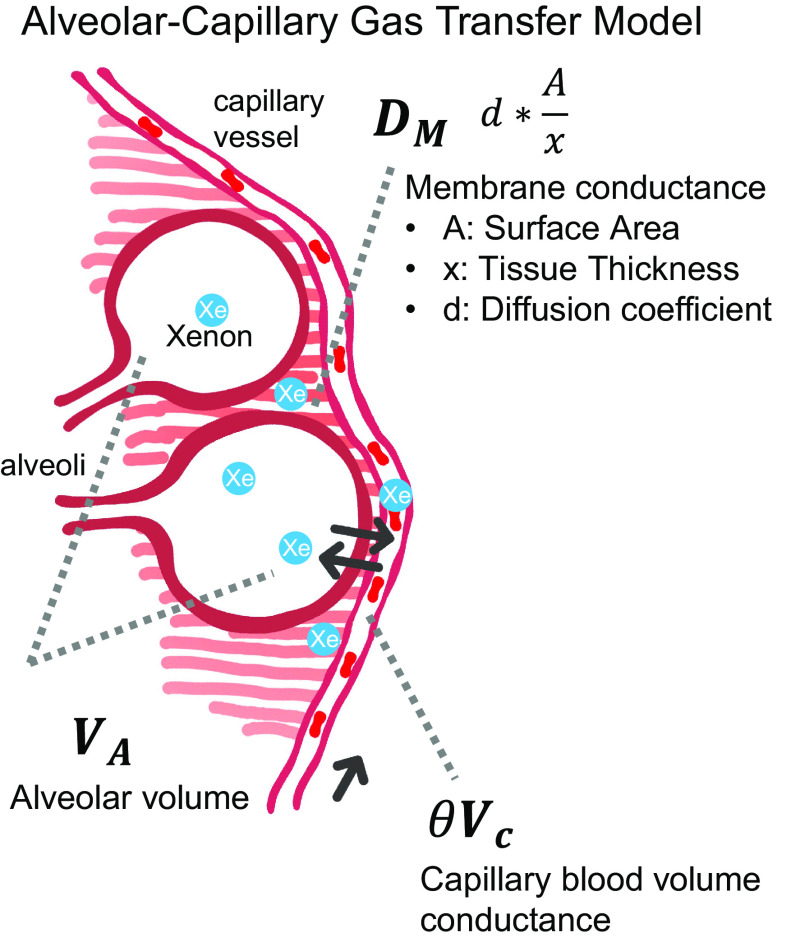

Here, we propose that the DM and Vc conductance terms can be estimated by 129Xe barrier uptake and RBC transfer, as illustrated in Fig. 2. In this framework, we use the image-derived measures of 129Xe barrier uptake and RBC transfer (relative to a healthy reference population) to estimate DM and θVc as follows:

Figure 2.

An alveolar-capillary gas exchange model to illustrate the components of the DLCO equation from Roughton and Forster (11).

| (3) |

| (4) |

where kB and kR are global coefficients to be determined by linear regression as described in Model Performance Analysis and Statistical Methods. Given that Barrel and RBCrel are dimensionless and VA is measured in L, the units for kB and kR are the same as KCO (mL/min/mmHg/L), while the product of the three has units of DLCO—mL/min/mmHg. Barrel (relative barrier transfer factor) and RBCrel (relative RBC transfer factor) are an individual subject’s mean barrier/gas and RBC/gas ratios divided by the corresponding values from the healthy reference cohort (Barref, RBCref).

| (5) |

| (6) |

As shown in Fig. 2, and explained by Roughton and Forster, Barrel conveys the membrane component of diffusing capacity, which scales linearly with gas diffusion coefficient d, surface area A and inversely with membrane thickness x as:

| (7) |

As seen in Eq. 7, DM can be diminished by either thickening of the blood-gas membrane x, such as in interstitial lung disease (ILD) (6), or reduction of surface area A such as in COPD/emphysema (9). While reduced surface area will similarly reduce Barrel, thickening of the membrane will actually increase 129Xe uptake in the barrier. Thus, to account for this, when Barrel exceeds the healthy reference mean, its inverse is used to capture the reduced membrane conductance.

| (8) |

In this way, the product of kB and the adjusted Barrel represents DM/VA and the product of kR with RBCrel represents θVc/VA. Inserting Eqs. (2)–(4) into Eq. (1) provides an estimate of KCO:

| (9) |

To calculate DLCO, the accessible alveolar volume VA can be estimated from ventilated volume (VV) of the gas-phase 129Xe image (26) by:

| (10) |

where kV is a unitless scaling factor determined by fitting. With knowledge of these three coefficients, the three components of the 129Xe MR images can be used to estimate VA, and the underlying factors that determine KCO and DLCO for any given subject.

Model Performance Analysis and Statistical Methods

Two linear regressions were performed in MATLAB (MathWorks Inc, MA) to determine the three coefficients that yielded the smallest mean squared error (MSE) across the entire 142 subject cohort. The coefficients kB and kR were derived by fitting the 129Xe-derived relative barrier and RBC to the measured KCO values while kV was calculated using 129Xe-derived measures of ventilated volume versus measured VA values. These coefficients were then used in conjunction with 129Xe MR image features of ventilation, barrier uptake, and RBC transfer to estimate VA, KCO, and DLCO for individual subjects. Note that both DLCO and the 129Xe RBC transfer values were uncorrected for hemoglobin.

To benchmark the performance of the model in estimating VA, KCO, and DLCO from 129Xe MRI features, the coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated. Welch’s t test was used to detect significant differences while accounting for unequal cohort sizes. Statistical significance was concluded when P < 0.05. All computations were performed using JMP 14 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Clinical and 129Xe MRI-Based Measurements in Different Cohorts

129Xe MR images of all subjects were successfully acquired with signal-to-noise (SNR) values of 11.7 ± 4.6, 12.6 ± 8.8, and 4.0 ± 2.7 for the gas, barrier, and RBC images. The 129Xe MRI-derived metrics of relative ventilated volume, barrier, and RBC transfer factor are shown in Table 2, along with the clinical measurements of VA, KCO, and DLCO across all six cohorts. All five patient cohorts were evaluated for significant differences relative to the healthy cohort, using Welch’s t test. VA and KCO were significantly reduced in all patient cohorts except for patients with Post-PH. Relative to the healthy cohort, DLCO was significantly lower in all patient groups. The 129Xe-MRI derived measure of relative ventilated volume, relative barrier transfer factor, and relative RBC transfer factor are lower across all patient cohorts relative to the healthy cohort, except for patients with Post-PH.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation of clinical measured VA, KCO, DLCO, and 129Xe MRI-derived metrics of ventilated volume, barrier transfer factor, and RBC transfer factor (relative to healthy reference values)

| Metrics (Means ± SD) | Healthy | COPD | IPF | NSIP | Pre-PH | Post-PH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA, L | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 4.3 ± 1.0* | 3.4 ± 0.9* | 2.9 ± 1.0* | 4.3 ± 1.5* | 4.6 ± 1.7 |

| KCO, mL/min/mmHg/L | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 1.3* | 3.4 ± 0.6* | 4.3 ± 0.9* | 3.4 ± 1.3* | 4.3 ± 1.4 |

| DLCO, mL/min/mm Hg | 26.3 ± 6.3 | 12.6 ± 4.7* | 11.5 ± 3.3* | 12.7 ± 5.5* | 14.8 ± 8.4* | 19.1 ± 7.1* |

| Rel. ventilated volume, % | 109 ± 17 | 95 ± 23* | 87 ± 18* | 74 ± 19* | 97 ± 23* | 103 ± 43 |

| Rel. barrier transfer factor, % | 85 ± 13 | 68 ± 19* | 55 ± 11* | 76 ± 13* | 77 ± 14* | 83 ± 12 |

| Rel. RBC transfer factor, % | 81 ± 26 | 38 ± 15* | 59 ± 18* | 52 ± 18* | 66 ± 25* | 70 ± 26 |

The 129Xe MRI-derived metrics were measured at FRC + 1 L. *Significantly lower values than those of the healthy cohort. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FRC, functional residual capacity; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; PH, pulmonary hypertension.

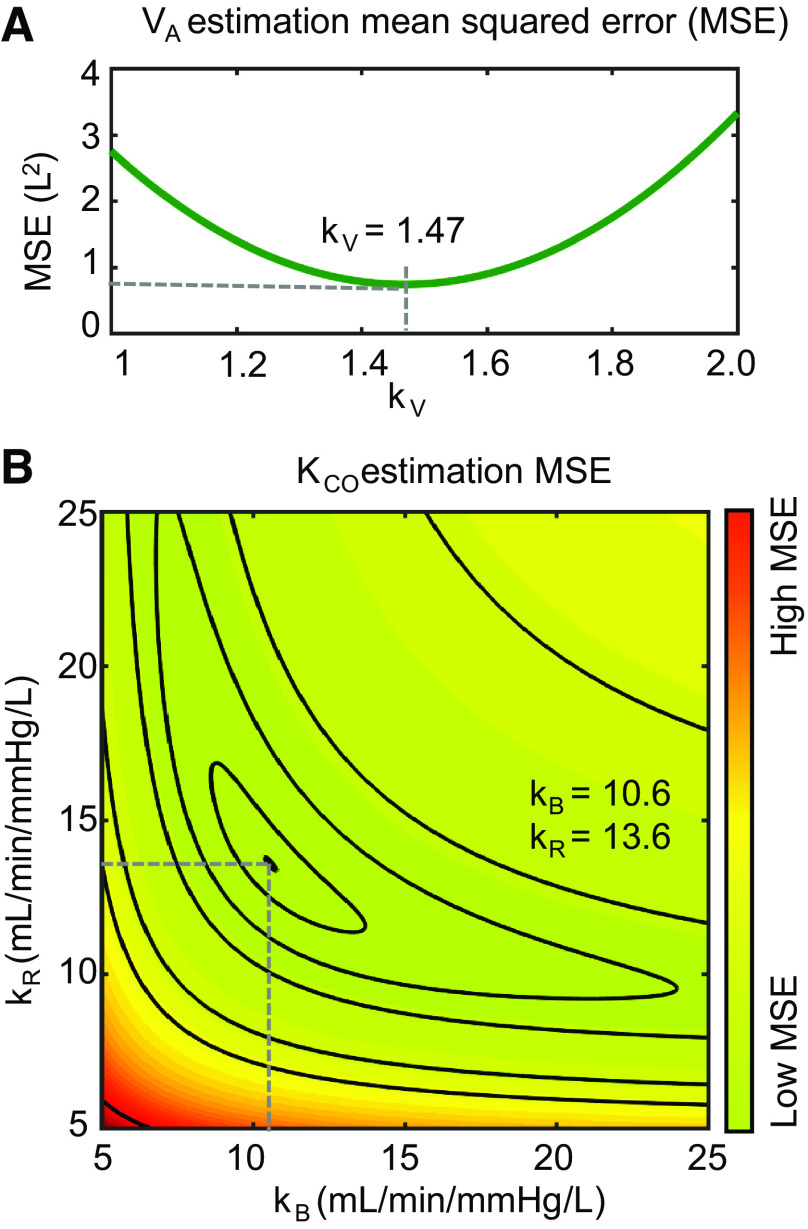

Fit Coefficients and Confidence Intervals

Figure 3 shows the results of minimizing the MSE to derive the fit coefficients kV, kB, and kR. Figure 3A shows the effect of changing kV value on MSE for estimating accessible alveolar volume VA, whereas Fig. 3B shows the surface plot that determines the combination of kB and kR that minimizes the MSE for image-estimated versus measured KCO. Collectively, this process yielded coefficients (with 95% intervals): kV = 1.47 [1.42, 1.52), kB = 10.6 [8.6, 13.6) mL/min/mmHg/L, and kR = 13.6 [11.4, 16.7) mL/min/mmHg/L. To examine the generalizability of the model, we also performed this same minimization on each combination of the five patient cohorts with the healthy volunteers. This yielded similar coefficients (mean value across five cohorts), albeit with larger confidence intervals: kV = 1.55 [1.53, 1.57], kB = 9.8 [9.3, 10.5] mL/min/mmHg/L, and kR = 16.4 [12.4, 20.5] mL/min/mmHg/L.

Figure 3.

Fitting the model to the entire cohort to calculate coefficients kV, kB, and kR. A: optimizing kV to minimize MSE for estimated VA. B: optimizing kB and kR to minimize MSE for estimated KCO. The contours delineate levels of similar MSE as a function of kB and kR. MSE, mean squared error.

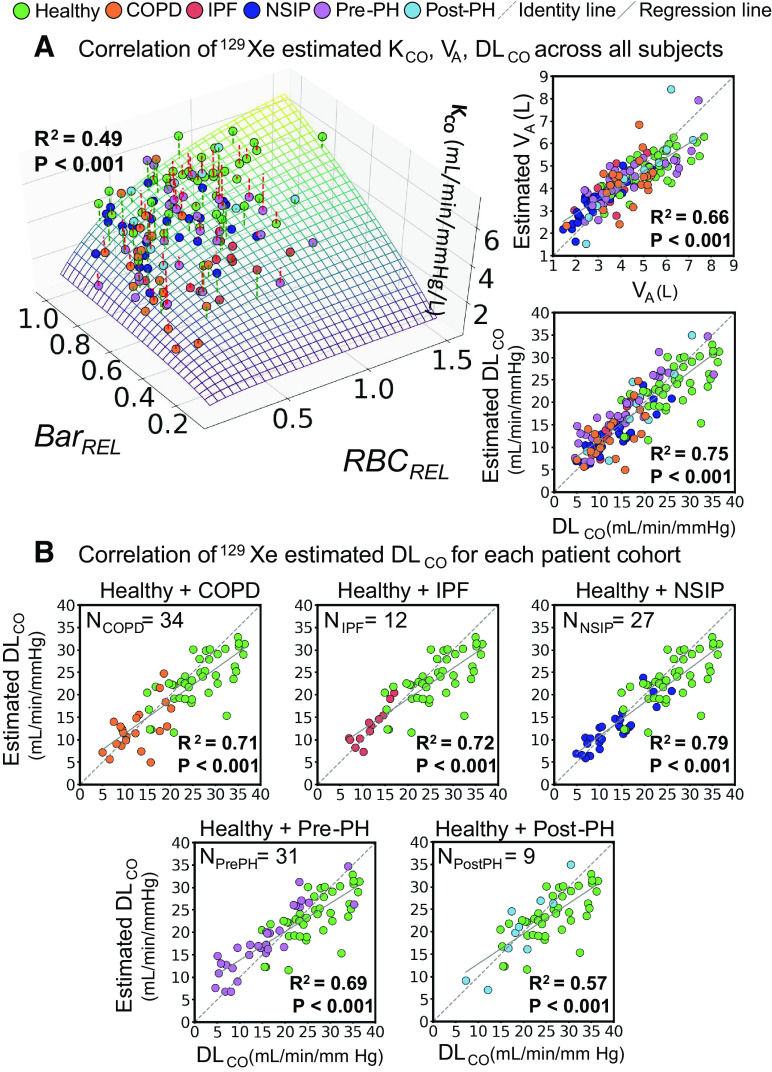

Correlation of 129Xe MRI-Based versus Measured DLCO and KCO

With these fit coefficients, it became possible to use the 129Xe MRI-derived metrics to estimate VA, KCO, and DLCO across all subjects in the study population and compare them to the clinically measured values. This is illustrated in Fig. 4A showing a 3D surface plot of the image estimated KCO as a function of Barrel and RBCrel, which is compared with measured KCO values (R2 = 0.49, P < 0.001). Also shown are the image-estimated versus measured VA (R2 = 0.66, P < 0.001). Multiplying the image-estimated VA and KCO provided the estimated DLCO, which had the strongest correlation (R2 = 0.75, P < 0.001) with the measured values. Moreover, these correlations were preserved when examined for each individual disease plus healthy volunteer cohort. As shown in Fig. 4B, the correlation of image-derived versus measured DLCO for the groups (P < 0.001) was R2 = 0.71 in COPD; R2 = 0.72 in IPF; R2 = 0.79 in NSIP; R2 = 0.69 in Pre-PH; and R2 = 0.57 in Post-PH.

Figure 4.

A: correlation of image-estimated versus clinically measured gas exchange parameters across all subjects. The 3D surface plot represents image estimated KCO as it depends on Barrel and RBCrel, while the markers show the clinically measured values. Those with a red dashed line are underestimated, whereas the green dashed line is overestimated. The graphs (right) show the correlation between image-estimated versus measured values for VA and DLCO. B: the DLCO correlations were preserved when examined within each individual patient cohort of COPD, IPF, NSIP, Pre-PH, and Post-PH. The dotted line is the line of identity and the solid line is the regression line. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; Pre-PH, precapillary pulmonary hypertension; Post-PH, postcapillary pulmonary hypertension; PFT, pulmonary function testing.

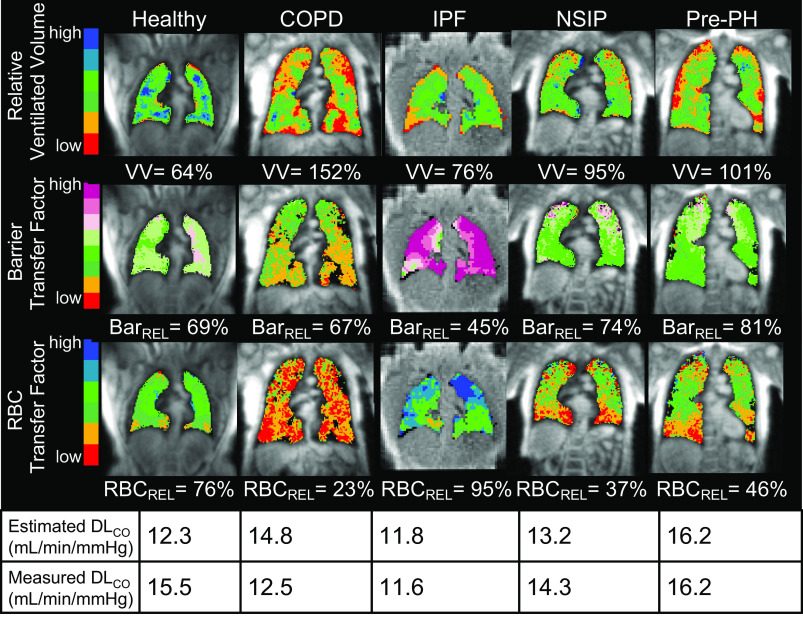

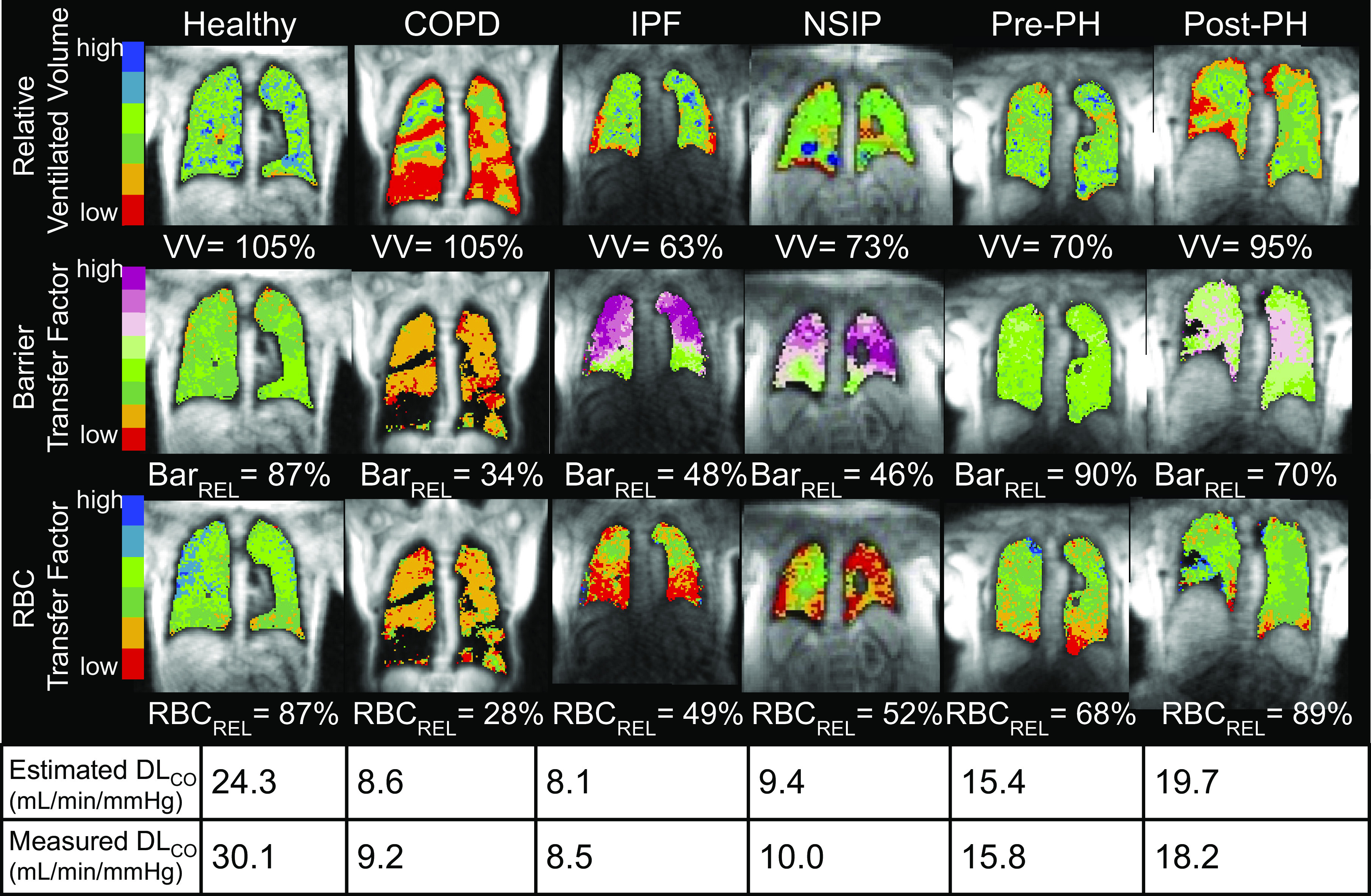

Using 129Xe Gas-Exchange MRI to Discern Underlying Contributions to DLCO in Representative Subjects

Figure 5 shows representative 129Xe gas-exchange MR images and the way in which relative ventilated volume, barrier, and RBC transfer factors can help understand the measured DLCO reported for each subject. The healthy subject exhibits relative ventilated volume, RBC, and barrier transfer factors that are close to the healthy reference range, producing a generally preserved DLCO. By contrast, the patients exhibit various combinations of reduced ventilated volume, relative barrier, or relative RBC that all serve to reduce DLCO. Interestingly, the COPD patient has significant ventilation defects (depicted in red on the ventilation map), but hyperinflation keeps the ventilated volume in the normal range. However, the patient has low relative barrier uptake (low membrane conductance) and poor relative RBC transfer (low capillary blood conductance) that combined to drive the overall DLCO below 10 mL/min/mmHg. In contrast, although the IPF and NSIP patients exhibited few ventilation defects, their ventilated volume was lower due to their restrictive diseases. In these patients, barrier uptake was higher than the reference (potentially due to thickening of the interstitial tissue) and led to lower specific membrane conductance (DM/VA). Combined with regional defects in RBC transfer (lower specific capillary blood volume conductance, Vc/VA), these disparate factors contributed to a DLCO in the same range as the patient with COPD. In the patient with precapillary PH, the primary contributors to decreased DLCO were smaller ventilated volume due to chest cavity size and reduced capillary blood volume conductance reflected in RBC transfer defects. The patient with postcapillary PH exhibited modestly reduced DLCO, driven primarily by slightly elevated barrier uptake, which reduced membrane conductance.

Figure 5.

Gas exchange images of representative subjects and their image-derived versus measured DLCO values. These examples show an array of ways in which the combination of reduced ventilated volume, diminished or elevated barrier uptake, and decreased RBC transfer all contribute to reduced DLCO.

Deconstructing the Origins of Reduced DLCO across Distinct Pathologies

The framework allows all three contributions to gas exchange to be independently examined and characterized regionally by 129Xe MRI. This is perhaps best illustrated in Fig. 6, which shows 129Xe MR images in a range of subjects with similar, moderately reduced DLCO values (11.6–16.2). 129Xe MRI permits gas exchange impairment to be understood in terms of individual contributions from VV, barrier transfer factor (thickening or lost surface area), and RBC transfer factor. This demonstrates that the low DLCO in the healthy subject is attributable to a smaller thoracic cavity volume (inflation at a time of imaging was 2.0 L vs. 3.4 L from the healthy reference cohort). The subject also had low hemoglobin level (10.2 g/dL), which likely caused the low RBCrel. The patient with COPD, although exhibiting numerous ventilation defects, still has a high ventilated volume, which somewhat compensates for significantly decreased barrier and RBC transfer factors to limit the reduction in DLCO. In the patient with IPF, barrier transfer factor is also reduced by the elevated barrier uptake potentially resulting from a thickened membrane. Interestingly, this patient shows relatively preserved RBC transfer, which is thought to be a feature of early-stage disease (6, 7). The combination of impaired barrier function with preserved RBC transfer led to an image-estimated KCO of 3.5 mL/min/mmHg/L, which agreed reasonably well with the measured KCO of 3.8 mL/min/mmHg/L. The decreased DLCO in the patients with NSIP and Pre-PH is primarily attributable to reduced capillary blood volume conductance, as evidenced by the RBC transfer defects in the caudal (basilar) portions of the lungs.

Figure 6.

129Xe MR images of subjects with similar DLCO measurements. The diffusion impairment among these subjects, measured by the global metric DLCO, can be independently quantified and spatially resolved by 129Xe images of ventilated volume to estimate VA, barrier uptake to estimate membrane conductance, and RBC transfer to estimate capillary blood volume conductance.

DISCUSSION

129Xe MRI Can Differentiate Alveolar Volume, Membrane, and Capillary Blood Volume Conductance Contributions to DLCO

The model described here enables using 129Xe MR imaging of ventilation, barrier uptake, and RBC transfer to measure and interpret the physiologically established concepts of alveolar volume, membrane conductance, and capillary blood volume conductance. It provides a framework to enable independent assessment of how each component contributes to the overall diffusion impairment measured by KCO or DLCO. For example, the relative VV can be reduced or enhanced by a variety of factors such as thoracic cavity volume, inhalation volume, ventilation defects, and posture. For example, the ventilated volumes in IPF (3.0 ± 0.5 L, P < 0.01) and NSIP (2.4 ± 0.6 L, P < 0.01) are both significantly lower than the healthy cohort (VV = 3.4 ± 0.6 L). This is consistent with significantly reduced VA observed in these cohorts and the well-known tendencies of these restrictive diseases to reduce lung volumes (27, 28). By contrast, VV is only modestly reduced in COPD, despite these subjects exhibiting significantly increased VDP (33 ± 18%, P < 0.01) compared with the healthy cohort (3 ± 2%). Instead, VV is maintained at nearly preserved levels by hyperinflation, which leads to a larger overall thoracic cavity volume.

The capillary blood volume conductance as measured by 129Xe RBC transfer is relatively straightforward to interpret. With the exception of the small (N = 9) Post-PH group, all patient groups exhibited statistically significant regional defects in RBC transfer, consistent with prior reports (9), and this indicates reduced capillary blood volume conductance. It is noteworthy that in the vast majority of subjects, these RBC transfer defects are predominantly found in the caudal (basilar) lung.

Perhaps the most intriguing of the three compartments is the membrane conductance, as reflected in the barrier uptake maps. This aspect of imaging can reflect both loss of diffusion surface area or airspace enlargement and potential thickening or alteration of the interstitial membrane. These opposing aspects of membrane conductance were incorporated by using the reciprocal of Barrel when it exceeded the normal reference value. For example, mean 129Xe barrier uptake was 102 ± 24% in the healthy cohort, but only 69 ± 23% in the patients with COPD (P < 0.01). This reduction in relative barrier signal is consistent with emphysematous loss of alveolar surface area (29). By contrast, relative 129Xe barrier uptake was significantly enhanced in both IPF (190 ± 40%, P < 0.01) and NSIP (134 ± 28%, P < 0.01), consistent with a thickening of the interstitial tissues and alveolar walls (27, 30). As a result, relative membrane conductance of 52% observed in the IPF cohort was the lowest of all groups.

Robust Correlations between 129Xe-Derived and Measured DLCO for All Disease Cohorts

While the model-fit coefficients were derived from the entire subject cohort, they remained relatively unchanged when calculated using each patient cohort individually. This suggests the model can be generalized to interpret DLCO values across a broad range of pulmonary disorders. Among our individual patient groups, the strongest correlation (R2 = 0.72) was observed in the interstitial lung diseases (IPF, NSIP). This compared reasonably favorably to the R2 = 0.88 correlation previously reported for the simple RBC/barrier ratio in IPF patients and healthy volunteers (6). However, in patients with COPD, the full three compartment model yielded a correlation (R2 = 0.71) that exceeded that of the simple RBC/barrier ratio correlation (R2 = 0.54). This reflects the inability of the RBC/barrier ratio alone to account for the role of ventilation defects and reduced barrier uptake in COPD caused by emphysematous loss of diffusion surface area (31). The lowest correlation for estimated versus measured DLCO was seen in patients with postcapillary PH, likely due to the limited number of subjects (N = 9), relatively small dynamic range of DLCO, and lower SNR in this cohort.

Model Coefficients and Diffusivity

Within the proposed framework, the coefficients kB and kR (10.6 vs. 13.6 mL/min/mmHg/L) can be interpreted as the specific conductances, DM/VA and θVc/VA that would be expected from a typical subject in the healthy reference cohort. These values can be estimated using the reference equations of Munkholm (32) for a hypothetical 20-yr-old, 170-cm tall male with Hgb of 14.6 g/dL that is representative of our reference cohort. This yields DM/VA = 25.9 mL/min/mmHg/L and a relative capillary blood volume of . To convert this to a specific conductance requires multiplying by the reaction rate θ between CO and blood, which is estimated (32) for males with Hgb = 14.6 g/dL and to be and yields . Combining these factors yields a predicted transfer coefficient KCO = 6.3 mL/min/mmHg/L, which is quite similar to the value of KCO = 6 mL/min/mmHg/L that is calculated from the imaging coefficients kB and kR. However, the two methods differ significantly in the relative resistance they ascribe to the membrane versus capillary blood volume compartments. Our imaging method suggests that the two contribute relatively equally to overall KCO, with barrier contributing ∼56% of the total impedance. While this is in reasonable agreement with the early physiological literature (11), it stands in contrast to the more modern physiological estimate above, which suggests that it is the capillary blood volume that accounts for 75% of the resistance. This is largely driven by recent advances in estimating the reaction rate θ between CO and blood (17, 33), which suggest θ to be ∼30% higher than original estimates. These differences, which must be investigated in more detail, suggest that the transfer of 129Xe to RBCs is less RBC hindered than the uptake of CO. It is a reminder that both 129Xe and CO are merely surrogate probes for the gases of interest, CO2 and O2. These differences are likely attributable to the distinct diffusivity (d) of each gas in the various compartments and that the fact that only CO reacts with blood.

Technique Differences between 129Xe MRI and DLCO Measurements

While the model presented in this study provides a means to relate 129Xe MR images to the physiologically established components of DLCO, there are differences between these measurements that must be considered. First, 129Xe MRI was acquired over a 15-s breath-hold, whereas DLCO was measured over a 10-s breath-hold. However, while these differences could subtly alter gas penetration and mixing, breath-hold time should not materially affect the comparison. The DLCO measurement is based on the physical quantity of CO removed from the airspaces. This is driven by an underlying rate constant per unit of barometric pressure, which removes more CO over time, multiplied by the accessible alveolar volume. The DLCO measurement is thus naturally proportional to breath-hold duration, which has been carefully standardized over the years. By contrast, the 129Xe gas dissolved in the alveolar membrane reaches RBCs within 30–50 ms (34) and a steady-state magnetization is established within 0.5 s. In this case, it is the RF pulsing that continually depletes the 129Xe magnetization reservoir in the capillary bed, acting as the “infinite sink” that provides sensitivity to diffusion. Thus, the 15-s breath-hold during imaging is used only to ensure sufficient image encoding to support 3D image resolution. A second difference is that 129Xe is more soluble than helium gas used to measure VA during a DLCO study. However, we do not anticipate that 129Xe solubility will adversely impact the VA measurement from ventilation images because at any given instant only 1%–2% of 129Xe is dissolved (3) and those atoms have a unique chemical shift and short T2* that renders them invisible on the gas-phase 129Xe image. Thirdly, 129Xe may distribute differently than helium gas when inhaled, potentially altering gas penetration. However, the potential impact on VA estimation would have been mitigated by the application of the scaling factor kV. Lastly, 129Xe and CO differ in their diffusivity (d) and only CO reacts with blood, as reflected by θ in the Roughton and Forster equations. However, in our framework, the diffusivity d was absorbed into the coefficient kB, whereas θ was absorbed into kR. In sum, 129Xe MRI provides a valuable complement to the clinical DLCO measurement, through its unique approach to assess the diffusion pathway and resolve topographic and physiological information of the membrane and RBC components.

A few factors may have affected DLCO measurements but were unlikely to have caused systematic biases. While DLCO is known to vary with time of day (35), neither our 129Xe scans nor DLCO measurements were scheduled with regard to time of day or timing relative to one another. We thus expect diurnal variation to introduce no systematic bias, but it could have somewhat lowered the observed correlations. It is also worth noting that subjects were in supine positioning for MRI but sit upright for DLCO measurements. This posture difference might have impacted PFTs (36) and DLCO measurements (37), but the difference was consistent across all subjects. Another factor to consider was oxygen use and the potential effects of smoking, both of which decrease clinically measured DLCO (38). We note that none of the subjects in this study were known smokers at the time of their studies, and none of our subjects received supplemental oxygen during their DLCO maneuvers as per ATS/ERS guidelines (21). However, ∼10% of subjects received oxygen during MRI, although this was discontinued before the xenon inhalation. Furthermore, as both DLCO (39, 40) and 129Xe RBC transfer (41) can be affected by subject hemoglobin level, normalizing hemoglobin level in our healthy population may provide more accurate reference values by which to interpret 129Xe metrics.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

We must recognize several limitations in this study. First, the group sizes for the different diseases were uneven, and the components of DLCO (DMCO and Vc) were not measured using sophisticated methods such as the two-step Roughton-Forster technique (11) or the double diffusion NO-CO technique (18). The uneven group sizes may have caused compromised model performance on underrepresented patient groups, such as the lower R2 (0.57) in the Post-PH cohort (n = 9). However, the inclusion of over 140 subjects in this study provides evidence that the model can be applied across diverse disorders. A second limitation was that the healthy volunteers were selected using fairly basic inclusion criteria (no smoking history and no known respiratory conditions). As a result, our healthy cohort was heterogeneous with subjects ranging from young athletes to older, more sedentary individuals, which could have contributed to the larger spread of estimated/clinical DLCO values of the healthy cohort (range from 15 to 35 mL/min/mmHg). A third limitation was that in this study, all subjects, including the healthy reference cohort, received the same total dose volume of 129Xe (1 L) regardless of their own lung capacity. This means that subjects with smaller lung volumes were imaged closer to their TLC, whereas larger subjects were closer to functional residual capacity (FRC). The different lung inflation states may have contributed to the 18 ± 14% relative error of VA estimation across all subjects, which is the largest specifically among patients with IPF (26 ± 20%), likely due to their relatively smaller lung volumes. There is now evidence from multiple studies that lung inflation state has a strong effect on other 129Xe metrics (10, 42). While the effect on ventilation is modest (43), the barrier/gas and RBC/gas ratios could be affected by as much as V−4/3 depending on the model of alveolar expansion we assume (44, 45). This could likely also explain the slight underestimation of DLCO among healthy subjects, who tend to better cooperate with inhalation instructions than patients, resulting in relatively higher lung inflation during imaging. These higher lung inflation levels would decrease RBC/gas ratios (RBC transfer) and thus reduce the estimated DLCO values (5, 42). Moreover, subjects with larger lung volumes may inadvertently perform some aspect of a Müller maneuver during their 129Xe breath-hold, which could increase pulmonary capillary blood volume (46). Thus, future studies will need to consider total gas volume as a reflection of the individual subject’s TLC or FVC (47). This is particularly pertinent in this study as DLCO and VA are measured at TLC, while 129Xe MRI was performed at functional residual capacity (FRC) plus the dose volume. For this reason, the coefficient kV was greater than one and used as a scale factor between 129Xe-derived ventilated volume (VV) and VA. However, we acknowledge that the difference between these two volumes is potentially more complex than can be captured by a single scaling factor. We anticipate that tailoring dose volumes to the individual subject’s lung volumes could ensure all subjects are imaged at relatively similar lung inflation states, which is likely to improve the accuracy of VA and DLCO estimation. Lastly, as DLCO can be reliably derived from postmortem specimens (48), the estimation of membrane and capillary blood volume conductance from 129Xe MRI should be compared and verified against measurements from postmortem specimens in future studies.

Conclusions

In this study, we proposed an interpretive framework to connect hyperpolarized 129Xe imaging metrics of ventilation, barrier uptake, and RBC transfer to the clinically used ones of alveolar volume, membrane conductance, and capillary blood volume conductance. This framework demonstrated strong correlation of using 129Xe metrics to identify various physiological mechanisms of gas exchange impairment measured by decreased DLCO. It can be readily applied to a broad range of pulmonary disorders and allows ventilation, barrier uptake, and RBC transfer to be assessed and monitored independently and regionally.

GRANTS

We gratefully acknowledge the support from National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL105643, R01HL126771, and HHSN268201700001C.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Driehuys is a founder of Polarean Imaging, a company that is working to commercialize hyperpolarized 129Xe gas MRI. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Z.W. and B.D. conceived and designed research; Z.W., L.R., E.A.B., D.M., J.L., A.C., and B.D. performed experiments; Z.W. and B.D. analyzed data; Z.W., L.R., R.M.T., A.S., Y.T.H., L.G.Q., J.G.M., S.R., and B.D. interpreted results of experiments; Z.W. prepared figures; Z.W. and B.D. drafted manuscript; Z.W., L.R., E.A.B., D.M., J.L., A.C., R.M.T., A.S., Y.T.H., L.G.Q., J.G.M., S.R., and B.D. edited and revised manuscript; Z.W., L.R., E.A.B., D.M., J.L., A.C., R.M.T., A.S., Y.T.H., L.G.Q., J.G.M., S.R., and B.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaushik SS, Robertson SH, Freeman MS, He M, Kelly KT, Roos JE, Rackley CR, Foster WM, McAdams HP, Driehuys B. Single-breath clinical imaging of hyperpolarized (129)Xe in the airspaces, barrier, and red blood cells using an interleaved 3D radial 1-point Dixon acquisition. Magn Reson Med 75: 1434–1443, 2016. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen RY, Fan FC, Kim S, Jan KM, Usami S, Chien S. Tissue-blood partition coefficient for xenon: temperature and hematocrit dependence. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 49: 178–183, 1980. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.49.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaushik SS, Freeman MS, Yoon SW, Liljeroth MG, Stiles JV, Roos JE, Foster W, Rackley CR, McAdams HP, Driehuys B. Measuring diffusion limitation with a perfusion-limited gas–hyperpolarized 129Xe gas-transfer spectroscopy in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Appl Physiol 117: 577–585, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00326.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z, He M, Bier E, Rankine L, Schrank G, Rajagopal S, Huang YC, Kelsey C, Womack S, Mammarappallil J, Driehuys B. Hyperpolarized (129) Xe gas transfer MRI: the transition from 1.5T to 3T. Magn Reson Med 80: 2374–2383, 2018. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z, Robertson SH, Wang J, He M, Virgincar RS, Schrank GM, Bier EA, Rajagopal S, Huang YC, O'Riordan TG, Rackley CR, McAdams HP, Driehuys B. Quantitative analysis of hyperpolarized 129Xe gas transfer MRI. Med Phys 44: 2415–2428, 2017. doi: 10.1002/mp.12264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang JM, Robertson SH, Wang Z, He M, Virgincar RS, Schrank GM, Smigla RM, O'Riordan TG, Sundy J, Ebner L, Rackley CR, McAdams P, Driehuys B. Using hyperpolarized (129)Xe MRI to quantify regional gas transfer in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax 73: 21–28, 2018. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rankine LJ, Wang ZY, Wang JM, He M, McAdams HP, Mammarappallil J, Rackley CR, Driehuys B, Tighe RM. (129)Xenon gas exchange magnetic resonance imaging as a potential prognostic marker for progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 17: 121–125, 2020. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201905-413RL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mummy D, Wang Z, Bier E, Tighe RM, Driehuys B, Mammarappallil J. Hyperpolarized 129Xe magnetic resonance imaging measures of gas exchange in non-specific interstitial pneumonia. Am Thorac Soc : A7894–A7894, 2020. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2020.201.1_MeetingAbstracts.A7894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z, Bier EA, Swaminathan A, Parikh K, Nouls J, He M, Mammarappallil JG, Luo S, Driehuys B, Rajagopal S. Diverse cardiopulmonary diseases are associated with distinct xenon magnetic resonance imaging signatures. Eur Respir J 54: 1900831, 2019. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00831-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qing K, Mugler JP 3rd, Altes TA, Jiang Y, Mata JF, Miller GW, Ruset IC, Hersman FW, Ruppert K. Assessment of lung function in asthma and COPD using hyperpolarized 129Xe chemical shift saturation recovery spectroscopy and dissolved-phase MRI. NMR Biomed 27: 1490–1501, 2014. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roughton FJ, Forster RE. Relative importance of diffusion and chemical reaction rates in determining rate of exchange of gases in the human lung, with special reference to true diffusing capacity of pulmonary membrane and volume of blood in the lung capillaries. J Appl Physiol 11: 290–302, 1957. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1957.11.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weatherley ND, Stewart NJ, Chan HF, Austin M, Smith LJ, Collier G, Rao M, Marshall H, Norquay G, Renshaw SA, Bianchi SM, Wild JM. Hyperpolarised xenon magnetic resonance spectroscopy for the longitudinal assessment of changes in gas diffusion in IPF. Thorax 74: 500–502, 2019. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdeen N, Cross A, Cron G, White S, Rand T, Miller D, Santyr G. Measurement of xenon diffusing capacity in the rat lung by hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI and dynamic spectroscopy in a single breath-hold. Magn Reson Med 56: 255–264, 2006. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frans A, Nemery B, Veriter C, Lacquet L, Francis C. Effect of alveolar volume on the interpretation of single breath DLCO. Respir Med 91: 263–273, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0954-6111(97)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Rodriguez-Roisin R. The 2011 revision of the global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD (GOLD)—why and what? Clin Respir J 6: 208–214, 2012. doi: 10.1111/crj.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes JM, Bates DV. Historical review: the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) and its membrane (DM) and red cell (θ.Vc) components. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 138: 115–142, 2003. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borland CDR, Hughes JMB. Lung diffusing capacities (DL) for nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO): the evolving story. Compr Physiol 10: 73–97, 2019.doi: 10.1002/cphy.c190001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zavorsky GS, Hsia CC, Hughes JM, Borland CD, Guenard H, van der Lee I, Steenbruggen I, Naeije R, Cao J, Dinh-Xuan AT. Standardisation and application of the single-breath determination of nitric oxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J 49: 1600962, 2017. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00962-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, Baur X, Hall GL, Culver BH, Enright PL, Hankinson JL, Ip MS, Zheng J, Stocks J,; ERS Global Lung Function Initiative. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 40: 1324–1343, 2012. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanojevic S, Graham BL, Cooper BG, Thompson BR, Carter KW, Francis RW, Hall GL; Global Lung Function Initiative TLCO Working Group, and T. Global Lung Function Initiative (TLCO). Official ERS technical standards: Global lung function initiative reference values for the carbon monoxide transfer factor for Caucasians. Eur Respir J 50: 1700010, 2017. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00010-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham BL, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Cooper BG, Jensen R, Kendrick A, MacIntyre NR, Thompson BR, Wanger J. 2017 ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J 49: 1600016, 2017. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00016-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaushik SS, Freeman MS, Cleveland ZI, Davies J, Stiles J, Virgincar RS, Robertson SH, He M, Kelly KT, Foster WM, McAdams HP, Driehuys B. Probing the regional distribution of pulmonary gas exchange through single-breath gas- and dissolved-phase Xe-129 MR imaging. J Appl Physiol 115: 850–860, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00092.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niedbalski PJ, Bier EA, Wang Z, Willmering MM, Driehuys B, Cleveland ZI. Mapping cardiopulmonary dynamics within the microvasculature of the lungs using dissolved (129)Xe MRI. J Appl Physiol (1985) 129: 218–229, 2020. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00186.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avants BB, Epstein CL, Grossman M, Gee JC. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med Image Anal 12: 26–41, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He M, Wang Z, Rankine L, Luo S, Nouls J, Virgincar R, Mammarappallil J, Driehuys B. Generalized linear binning to compare hyperpolarized (129)Xe ventilation maps derived from 3D radial gas exchange versus dedicated multislice gradient echo MRI. Acad Radiol 27: e193–e203, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2019.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart NJ, Chan HF, Hughes PJC, Horn FC, Norquay G, Rao M, Yates DP, Ireland RH, Hatton MQ, Tahir BA, Ford P, Swift AJ, Lawson R, Marshall H, Collier GJ, Wild JM. Comparison of He-3 and Xe-129 MRI for evaluation of lung microstructure and ventilation at 1.5T. J Magn Reson Imaging 48: 632–642, 2018. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Travis WD, Hunninghake G, King TE, Lynch DA, Colby TV, Galvin JR, Brown KK, Chung MP, Cordier J-F, Du Bois RM, Flaherty KR, Franks TJ, Hansell DM, Hartman TE, Kazerooni EA, Kim DS, Kitaichi M, Koyama T, Martinez FJ, Nagai S, Midthun DE, Müller NL, Nicholson AG, Raghu G, Selman M, Wells A. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia—report of an American Thoracic Society project. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177: 1338–1347, 2008[Erratum inAm J Respir Crit Care Med178: 211, 2008]. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1685OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz DA, Van Fossen DS, Davis CS, Helmers RA, Dayton CS, Burmeister LF, Hunninghake GW. Determinants of progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Res Crit Care Med 149: 444–449, 1994. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.2.8306043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J 33: 1165–1185, 2009. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00128008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, et al., ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 788–824, 2011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Douglas IS, Nana-Sinkam PS, Lee JD, Tuder RM, Nicolls MR, Voelkel NF. Is alveolar destruction and emphysema in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease an immune disease? Proc Am Thorac Soc 3: 687–690, 2006. doi: 10.1513/pats.200605-105SF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munkholm M, Marott JL, Bjerre-Kristensen L, Madsen F, Pedersen OF, Lange P, Nordestgaard BG, Mortensen J. Reference equations for pulmonary diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide and nitric oxide in adult Caucasians. Eur Respir J 52: 1500677, 2018. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00677-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zavorsky GS, Quiron KB, Massarelli PS, Lands LC. The relationship between single-breath diffusion capacity of the lung for nitric oxide and carbon monoxide during various exercise intensities. Chest 125: 1019–1027, 2004. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.3.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Driehuys B, Cofer GP, Pollaro J, Mackel JB, Hedlund LW, Johnson GA. Imaging alveolar-capillary gas transfer using hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 18278–18283, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608458103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Medarov BI, Pavlov VA, Rossoff L. Diurnal variations in human pulmonary function. Int J Clin Exp Med 1: 267–273, 2008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz S, Arish N, Rokach A, Zaltzman Y, Marcus EL. The effect of body position on pulmonary function: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med 18: 159, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0723-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peces-Barba G, Rodriguez-Nieto MJ, Verbanck S, Paiva M, Gonzalez-Mangado N. Lower pulmonary diffusing capacity in the prone vs. supine posture. J Appl Physiol (1985) 96: 1937–1942, 2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00255.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sansores RH, Pare PD, Abboud RT. Acute effect of cigarette smoking on the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity of the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis 146: 951–958, 1992. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.4.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes JM, Pride NB. Examination of the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DL(CO)) in relation to its KCO and VA components. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186: 132–139, 2012. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201112-2160CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller A, Thornton JC, Warshaw R, Anderson H, Teirstein AS, Selikoff IJ. Single breath diffusing capacity in a representative sample of the population of Michigan, a large industrial state. Predicted values, lower limits of normal, and frequencies of abnormality by smoking history. Am Rev Respir Dis 127: 270–277, 1983. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang YV. MOXE: a model of gas exchange for hyperpolarized 129Xe magnetic resonance of the lung. Magn Reson Med 69: 884–890, 2013. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hahn AD, Kammerman J, Evans M, Zha W, Cadman RV, Meyer K, Sandbo N, Fain SB. Repeatability of regional pulmonary functional metrics of hyperpolarized (129)Xe dissolved-phase MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 50: 1182–1190, 2019. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hughes PJC, Smith L, Chan HF, Tahir BA, Norquay G, Collier GJ, Biancardi A, Marshall H, Wild JM. Assessment of the influence of lung inflation state on the quantitative parameters derived from hyperpolarized gas lung ventilation MRI in healthy volunteers. J Appl Physiol (1985) 126: 183–192, 2019. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00464.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glazier JB, Hughes JM, Maloney JE, West JB. Measurements of capillary dimensions and blood volume in rapidly frozen lungs. J Appl Physiol 26: 65–76, 1969. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1969.26.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smaldone GC, Mitzner W. Viewpoint: unresolved mysteries. J Appl Physiol (1985) 113: 1945–1947, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00545.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith TC, Rankin J. Pulmonary diffusing capacity and the capillary bed during Valsalva and Muller maneuvers. J Appl Physiol 27: 826–833, 1969. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1969.27.6.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qing K, Tustison NJ, Altes TA, Ruppert K, Mata JF, Miller GW, Guan S, Ruset IC, Hersman FW, Mugler JP. Gas uptake measures on hyperpolarized xenon-129 MRI are inversely proportional to lung inflation level. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med 1488: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weibel ER. Lung morphometry: the link between structure and function. Cell Tissue Res 367: 413–426, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2541-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]