Abstract

A growing number of known species possess a remarkable characteristic – extreme resistance to the effects of ionizing radiation (IR). This review examines our current understanding of how organisms can adapt to and survive exposure to IR, one of the most toxic stressors known. The study of natural extremophiles such as Deinococcus radiodurans has revealed much. However, the evolution of Deinococcus was not driven by IR. Another approach, pioneered by Evelyn Witkin in 1946, is to utilize experimental evolution. Contributions to the IR-resistance phenotype affect multiple aspects of cell physiology, including DNA repair, removal of reactive oxygen species, the structure and packaging of DNA and the cell itself, and repair of iron-sulfur centers. Based on progress to date, we overview the diversity of mechanisms that can contribute to biological IR resistance arising as a result of either natural or experimental evolution.

The study of resistance to IR

For most of the geological history of our planet, environments that expose organisms to high levels of IR have been absent. That has changed with the modern military, industrial, and medical introduction of nuclear, X-ray, and other high-level sources of IR. The continued proliferation of these devices makes it ever more important to understand the effects of IR on biological systems. Although drugs or stressors such as desiccation (see Glossary) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) may mimic the damage caused by IR, the diversity of IR sources and the extent of damage caused sets IR apart from other forms of stress. Research in the field of radiation biology attempts to address at least four questions. First, what are the primary targets of IR in a cell? All molecules in a cell are subject to damage. Which targets, when damaged, elicit toxicity and death? Second, where and how did extreme resistance to IR arise in nature, and what mechanisms underlie this resistance? Third, given the relative absence of IR in natural environments, are there mechanisms of IR resistance that are not represented in natural IR extremophiles, whose evolution was driven by other forms of selection? This question can be approached by experimental evolution, an unbiased strategy where IR itself becomes the agent of selection. Finally, are there strategies that can be deployed to protect organisms, including humans, in environments with elevated levels of IR? A current understanding of the first three questions is the focus of this review, which may eventually provide a breakthrough for the final question.

The nature and effects of IR

The extraordinary ability of microbes to survive in and adapt to harsh conditions (i.e., extreme temperatures, low nutrient availability, high salt concentrations) is now a well-known and highly studied phenomenon. Of the stresses that life can overcome, IR is perhaps the most surprising. The capacity of bacteria to adapt to radiation was demonstrated by Evelyn Witkin in 1946 [1,2]. As described in the following text, organisms with extremophile levels of resistance to IR were discovered in the 1950s. Background radiation from sources such as radioactive isotopes of metals and cosmic radiation is ubiquitous, but generally at levels that are too low to trigger evolution of extremophile levels of resistance [3].

Human activity has changed this situation with the advent of nuclear power and associated nuclear waste dumps, radiation treatments for cancer, radiation used for sterilization, X-ray use in medicine, and much more. How IR deposits energy as it interacts with biological molecules is dictated by the type of IR. IR consists of high-energy particles with sufficient energy to ionize molecules with which they come into contact. The major types of IR are alpha particles (He nuclei), beta particles (electrons), and gamma/X-rays (photons), and energy deposition and particle penetrance are inversely correlated. Alpha particles deposit a large amount of energy along a short track, whereas gamma rays deposit less energy over a long track [4].

IR may cause severe oxidative damage to all cellular components, primarily through the generation of ROS due to the radiolysis of intracellular water [5,6]. Radiolysis caused by gamma irradiation initially produces excited water or ionized water plus an electron:

H2O → H2O * (excited water) or H2O+ + e−

Relaxation of these species on a femtosecond timescale generates hydroxyl radicals (●OH) and solvated electrons. The hydroxyl radicals (●OH) react rapidly with whatever organic molecule or metal may be nearby. Additional reactions of the hydroxyl radicals and solvated electrons produce diffusible ROS with comparatively much longer half-lives, such as hydrogen peroxide and superoxide ions (HO2●), leading to additional oxidative damage. At-risk cellular components are governed by proximity to newly-generated ●OH [4] and reactivity with respect to H2O2.

We briefly address here the first question posed in the introduction: what are the primary targets of IR in the cell? IR-induced oxidation of membrane lipids [7], intracellular protein [8–12], and genomic DNA [13–15] have all been implicated as a cause of IR-mediated cell death. The types of oxidative damage imposed on each of these molecular classes are complex. Complete cataloguing of these damage events is underway but is still in its infancy [5,6,10,12,16–18]. A few things can be said. For most of the history of the field of radiation biology, extensive damage to genomic DNA was considered to be the primary determinant of IR-mediated cell death. DNA strand breaks mediated by ●OH attack are particularly dangerous. When breaks occur on both strands, mediated either by nearby breaks created in both strands by clusters of (●OH) or a break in a template strand encountered by the replication fork, double-strand breaks (DSBs) result and are lethal if unrepaired [5,19].

IR-induced oxidative damage to proteins and amino acids is being studied, particularly in vitro [5,16,18]. The reaction of hydrogen peroxide with cysteine residues is particularly notable, and often leads to key biological responses [20–22]. The cysteine residues of some proteins, such as glyceraldehyde 3′-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), are much more H2O2-susceptible than others [10,12,21,23–25]. Fenton chemistry involving H2O2 and ferrous iron can further damage iron-sulfur clusters and mononuclear iron centers [26–30].

The prototype for IR-resistant organisms, the bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans, has an enhanced capacity for repairing shattered chromosomes after exposure to irradiation. This bacterium also exhibits an impressive capacity to protect its proteome from oxidative damage [8–11]. An examination of this organism has led Daly, Radman, and their coworkers to highlight protein oxidation and inactivation as the primary cause of cell death when non-IR-resistant species are irradiated, rather than DNA damage [8–11]. However, early efforts to quantify intracellular protein oxidation indicated that IR-inflicted damage to the proteome is relatively modest, even in E. coli [10,12]. Apart from heavy and targeted oxidation of a few proteins such as GAPDH and the elongation factor EF-Tu, very few E. coli proteins are oxidized reproducibly and at levels that would suggest widespread inactivation [10,12]. The oxidation of GAPDH is highly targeted to one active site Cys residue, which is converted to the sulfonic acid form in three steps [10,12,21,23–25]. The resulting inactivation of this central glycolytic enzyme would have the effect of diverting more glucose catabolism through the pentose phosphate pathway, generating NADPH and reduced glutathione to break down hydrogen peroxide.

The conclusion that untargeted protein oxidation occurs only at low levels is based on studies that are admittedly limited and incomplete. If confirmed by further work, these observations would again focus attention back to DNA damage as a primary cause of cell death upon irradiation. This theme is reinforced by the results of the experimental evolution experiments described in the following text. Additional research will be necessary to systematically define what oxidation events result in cell death as a result of irradiation.

Radiation resistance in bacteria and other organisms

IR is not well tolerated by most organisms. The lethal dose for a human being is 3–10 Gray (Gy; 1 Gy = 100 rads) [31,32]. Despite the severe and multifaceted damage induced by IR, resistance to extreme doses of IR arose naturally in species in all domains of life [9,33]. Among the Eukarya, tardigrades (commonly known as ‘water bears’) are popular and well-studied animals that are highly desiccation- and radiation-resistant, being capable of surviving doses of 2000–4000 Gy without any loss in viability [34,35]. These amazing, microscopic creatures utilize an expanded arsenal of DNA repair proteins and superoxide dismutases [36,37], tardigrade-unique DNA protection mechanisms [36,38], and desiccation-resistant proteins [39] to both prevent and repair the extensive damage caused by high doses of IR. As discussed later in the context of bacterial IR resistance, the evolution of IR resistance in tardigrades was likely a byproduct of selection to survive desiccation.

Melanized fungi are another group of eukaryotes garnering interest in the field of radiation biology [40]. In part through the use of melanin, these microbes can survive extreme levels of both chronic and acute irradiation [41,42], and doses of well over 10 000 Gy are required to sterilize fungal cultures [43]. Such broad-spectrum radiation resistance has led to isolation of these fungi across numerous high-radiation environments such as Antarctic mountains and Chernobyl. They have even been found as contamination on the International Space Station [40]. In one study of the melanized black fungus Exophiala dermatitidis, an increase in IR resistance was achieved using an experimental evolution protocol similar to that described later in this review [44]. Genomic sequencing revealed that non-homologous end-joining was inactivated in the evolved cells, and the importance of homologous recombinational DNA repair was enhanced as a mechanism to survive IR exposure. Non-homologous end-joining is inherently mutagenic and may be unsuitable for repair of the extensive DSBs created by high levels of IR exposure.

Archaea, a domain replete with extremophiles, are represented in the IR-resistant world by the halophilicHaloarchaea. These highly irradiation- and desiccation-resistant archaea withstand doses of ∼3000 Gy with little to no loss in viability [45]. Haloarchaea are polyploids, and some species maintain dozens of chromosomal copies [46]. Such genetic redundancy lends itself to the repair of numerous DSBs generated by IR exposure through homologous recombination. The polyploidy of Haloarchaea comes in addition to a somewhat specialized complement of DNA repair and ROS-metabolizing proteins [47,48]. Furthermore, the carotenoid-based pigmentation of Haloarchaea affords protection from IR, likely acting as an antioxidant [45]. Interestingly, the halophilic nature of the Haloarchaea exposes them to the radioactive isotope 40K that is present in halite [49]. Some have speculated that increased background IR from this isotope may have spurred selection for radioresistance in these species. However, the long half-life of 40K and its low abundance leads to chronic IR exposures that seem unlikely to direct evolution of extreme IR resistance. Desiccation may again have been the key agent of selection. Given their extreme radiation and desiccation resistance, Haloarchaea have been isolated from fluid inclusions within salt crystals after several years and perhaps over much longer timescales [49–52].

Although several bacterial phyla have radioresistant members, the phylum most enriched for this phenotype is that of Deinococcus-Thermus [4]. Perhaps the best-studied model organism for radioresistance is the Gram-positive bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans, which will be discussed in greater detail in the following text.

Deinococcus radiodurans

D. radiodurans was first isolated in 1956 [53]. Members of the Deinococcus genus have now been isolated worldwide and are known for their extreme resistance to IR and desiccation [54–58]. In particular, surviving cells from a D. radiodurans culture can be isolated even after treatment with doses in excess of 10 000 Gy, ∼200-fold higher than the lethal human dose of IR [4]. Under some irradiation conditions, Deinococcus can survive irradiation to 5000 Gy with no lethality [54,56–58]. By contrast, 99% of an E. coli culture is killed after exposure to 500–750 Gy [4]. Our current understanding of the mechanisms of IR resistance utilized by D. radiodurans have been thoroughly discussed [4,58,59]. Briefly, this bacterium is capable of extraordinary feats of active repair and attenuation of IR-induced damage (through DNA repair and ROS-metabolizing enzymes) as well as passively suppressing damage the through accumulation of low-molecular weight ROS scavengers.

D. radiodurans is capable of repairing hundreds of DSBs generated by kGy doses of IR, utilizing a repair mechanism termed extended synthesis-dependent strand annealing (ESDSA) [13]. This pathway is initially dependent on high levels of de novo DNA synthesis, using broken ends of DNA as primers. Once these single-stranded (ss)DNA overhangs are generated, RecA-mediated strand annealing and homologous recombination facilitate repair of shattered chromosomes.

D. radiodurans relies on a fairly standard set of DNA repair enzymes, although some novel DNA repair activities have been described. D. radiodurans possesses homologs of the bacterial proteins involved in homologous recombination [involved in single-strand break (SSB) and DSB repair], mismatch repair, nucleotide excision repair, and base excision repair [4,58]. Notably, at least some D. radiodurans enzymes involved in these pathways behave differently from their canonical E. coli homologs, as is the case for the enzyme responsible for homologous recombination, RecA [4]. Furthermore, the lack of two key DSB repair proteins (RecB and RecC) leads to dependence on the RecFOR pathway for RecA-dependent DSB repair in D. radiodurans [58,60]. By contrast, in E. coli, RecFOR is thought to largely function in SSB repair [61,62]).

In addition to the ‘normal’ pathways of DNA repair, D. radiodurans encodes a variety of unique DNA repair proteins [4,58]. DdrA and PprA are two of the best-characterized Deinococcus-specific repair proteins, and both are highly expressed after exposure to IR [63]. DNA DSBs are highly vulnerable to exonuclease degradation that can lead to irreversible genome loss. DdrA is involved in the protection of double-stranded DNA ends (generated by DSBs) from exonuclease degradation [64], and is expressed together with DdrB and DdrC, which appear to protect ssDNA from nuclease degradation and promote annealing [58,63]. PprA may be involved in non-homologous end joining (a RecA-independent pathway of DSB repair) [65], or perhaps chromosome segregation after chromosomes are repaired following IR exposure [58]. Given the significant DNA damage induced by IR, genetic studies have shown that deletion of many of the aforementioned enzymes severely reduces (and even eliminates) the radioresistant phenotype of D. radiodurans [63,66,67]. Thus, DNA repair innovations are clearly part of the IR-resistance phenotype.

D. radiodurans additionally relies on a remarkable ability to attenuate ROS generated by IR or desiccation. This bacterium utilizes a typical set of ROS-metabolizing enzymes (catalases, superoxide dismutases, peroxidases, etc.) [58,59]. However, passive mechanisms of ROS removal set D. radiodurans apart [58,59,68]. The carotenoid-based pigment of D. radiodurans (giving the bacterium its trademark pink hue) plays a role in resistance to IR, likely owing to its ability to scavenge ROS [58]. In addition, D. radiodurans accumulates extremely high concentrations of Mn2+ (∼0.2–4 mM) [59,68,69]. The high levels of this cation, complexed with other low-molecular weight species in the cytoplasm (such as peptides, nucleotides, and inorganic phosphate), play a demonstrable role as an oxidative scavenger, contributing greatly to the IR resistance of this bacterium [68,70]. A large body of work from Daly and colleagues demonstrated that these Mn complexes act to principally protect proteins from IR-induced oxidation and, presumably, from inactivation [70]. This discovery has further led to investigation into the roles that Mn/peptide mixtures may be able to play as ‘shields’ to protect organisms from the effects of IR exposure [70–73]. Furthermore, the intracellular Mn:Fe ratio has been correlated with IR resistance of organisms across domains of life – a high Mn:Fe ratio suggests high IR resistance in that organism [69]. However, D. radiodurans and other organisms have undergone additional adaptations to accommodate the high levels of Mn2+, perhaps through the use of this cation as a cofactor for several proteins [59,74] and by carefully regulating Mn homeostasis [75]. Indeed, Mn toxicity is a well-known phenomenon in other organisms [29], and excess Mn accumulation can even inhibit the growth of D. radiodurans [75].

Can radioresistance evolve in nature?

Although halophilic organisms are a potential exception, the background dose of IR experienced by organisms on Earth is relatively low. From the beginnings of life on Earth ∼4 billion years ago to today, the terrestrial background IR has decreased from ∼1.6 mGy to 0.66 mGy per year, whereas organisms with high concentrations of potassium have experienced doses from 7 to 1.35 mGy/year over that same time-period [76]. Thus, it is unlikely that IR has played a significant role in selecting for radioresistant species. Instead, desiccation tolerance is the principal correlate with IR resistance across domains of life [54,55,63,77–79]. Desiccation, like IR, generates severe oxidative stress leading to an accumulation of DNA DSBs that must be repaired for the organism in question to recover when environmental conditions permit [4,77,80,81]. The effects of desiccation may explain the evolution of specialized genome-protection measures such as the DNA end-binding protein DdrA [64]. DNA repair is highly dependent on ATP. Upon desiccation, the metabolism needed to generate ATP is not present. Small amounts of water are always present, leading to the very slow accumulation of DNA strand breaks due to hydrolytic cleavage. Because exonucleases do not require ATP to function, desiccation would lead to genome loss in the absence of DNA end-protection mechanisms. The same type of mechanisms could facilitate survival after IR exposure.

Despite the constant, low dose of background IR over evolutionary time [76], recent human activity has had profound effects on the levels present in certain environments. Testing of nuclear weaponry in the atmosphere and at specific testing sites has dramatically altered the levels of radionuclides across the globe. Isotopes of I and Cs (specifically 131I and 137 Cs, respectively) have been two of the most prominent radioactive species, although 131I has decayed rapidly. In particular, the devastating meltdown of the nuclear reactor at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in 1986 has significantly altered the surrounding environment [82]. Studies are beginning to elucidate the effects of the excess irradiation, currently at ∼1 mGy/h, on local species [82]. Interestingly, melanized fungi appear to thrive in the new environment generated by the Chernobyl disaster. One recent study has even proposed that these fungi have developed radiotropism, and are capable of using the energy of IR to carry out metabolism in a process dubbed ‘radiosynthesis’ [40], an idea we regard with skepticism. Nevertheless, despite the tragedy surrounding their creation, areas such as those around Chernobyl provide fertile venues to study the effects of IR as a selective agent in nature [82].

History of the experimental evolution of radiation resistance

Like all organisms, bacteria in the genus Deinococcus are complex [58]. Given the desiccation-driven evolution of Deinococcus, with IR resistance as a byproduct, it is not clear that this organism possesses all possible adaptations to IR exposure. Further progress based on the properties of this one species will require both intuition and serendipity, possibly involving mechanisms no investigator has so far thought to consider. There may be effective biological strategies to survive irradiation that are not present in Deinococcus. Experimental evolution provides an alternative approach, with the advantage that it is intrinsically unbiased. Convert an IR-sensitive species to an IR-resistant species and see what changes.

Research into the selection of radioresistant phenotypes is a field with deep history, and some of the major milestones are listed in Table 1 [2,14,83–88]. The pioneering work of Evelyn Witkin in 1946 [1,2] showed that Escherichia coli B could produce radiation-resistant variants when selected for using UV radiation. The mutant generated (termed B/r, for E. coli B resistant to radiation) showed resistance to both UV and IR, and, importantly, maintained this phenotype in the absence of selection. To our knowledge, the mutation(s) which produced the radioresistant phenotype of B/r have never been identified.

Table 1.

Milestones in experimental evolution of radiation resistance

| Study | Organism | Radiation source | Key takeaways | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Witkin 1946 | E. coli B1 | UV | Generated E. coli B/r, the first-documented radiation-resistant strain. It was demonstrated that the radiation-resistant phenotype was heritable and stable | [1,2] |

| Erdman, Thatcher, and MacQueen 1961 | E. coli, Streptococcus faecalis, Clostridium botulinum, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella gallinarium | 60Co (? Gy/minute) | Resistance to IR can increase with iterative cycles of selection, but resistance reached a plateau. IR resistance was not developed by all bacteria tested, including S. gallinarium and two strains of S. aureus | [84] |

| Davies and Sinskey 1973 | Salmonella typhimurium LT2 | 60Co (51 Gy/minute); UV | Resistance to IR and UV increased over 84 cycles of selection, reaching similar levels of radioresistance to Deinococcus radiodurans. IR-resistant isolates exhibited increased DNA polymerase and ligase activity, suggesting that DNA repair was enhanced | [83] |

| Parisi and Antoine 1974 | Bacillus pumilus | 60Co (25 Gy/minute) | IR resistance of B. pumilus increased over 21 cycles of selection, and was stable without selection. Evolved isolates lost spore formation ability and exhibited auxotrophies | [85] |

| Harris 2009 | E. coli K12 | 60Co (19 Gy/minute) | Generated four replicate populations of IR-resistant E. coli with 20 cycles of selection. For the first time, determined that variants of RecA (D276A, A290S) and e14 prophage excision enhance IR resistance | [88] |

| Byrne 2014 | E. coli K12 | 137Cs (7 Gy/minute) | Demonstrated that the variants of RecA (D276N), DnaB (P80H), and YfjK (A151D) account for the IR resistance of evolved isolate CB2000 | [14] |

| Bruckbauer 2019b | E. coli K12 | Electron beam (72 Gy/minute) | Generated four new populations of IR-resistant E. coli with 50 cycles of selection with a more powerful IR source. Determined that variants of RpoB (S72N), RpoC (K1172I), RecD (A90E), and RecN (K429Q) enhance IR resistance. Deep sequencing of genomic DNA from whole populations reveals the complexity of the evolving populations | [86] |

| Bruckbauer 2020a | E. coli K12 | Electron beam (72 Gy/minute) | Continued experimental evolution with an additional 50 cycles of selection with the electron beam source | [87] |

Erdman and colleagues in 1961 were the first to demonstrate that IR resistance could increase with iterative cycles of selection. They set out to determine the capacity of common food-borne pathogens to develop resistance to IR, complementing efforts to develop irradiation as a means to sterilize food [84]. Coincidentally, it was contamination of irradiated canned meat that led to the discovery and isolation of Micrococcus radiodurans [53], now known as Deinococcus radiodurans [89].

Davies and Sinskey [83] extended this work using experimental evolution (84 cycles of selection) to generate Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains that were nearly as radioresistant as D. radiodurans. They further demonstrated that these bacteria had increased DNA polymerase and DNA ligase activity, for the first time suggesting the evolved IR resistance was founded in enhanced DNA repair. However, the complete molecular basis of the IR-resistance phenotype was not accessible using the technologies then available.

Each of these studies was carried out before the invention and widespread adoption of modern genomic DNA sequencing technologies [90]. The ability to generate a phenotype of interest through mutation at an unknown locus in the chromosome and then identify that mutation using whole-genome sequencing has revolutionized the field of experimental evolution. One early effort to apply an ‘omic’ approach occurred in 2007. DeVeaux et al. experimented with the halophilic archaean Halobacterium sp. NRC-1, an organism highly resistant to radiation, desiccation, and salinity [91]. After four cycles of high-level irradiation, mutants were generated with an ability to survive IR treatment surpassing that of D. radiodurans. Using microarrays to carry out whole-genome transcriptome analysis, these workers detected increased expression of an operon including two genes encoding ssDNA-binding proteins (RPA) and another gene of unknown function. In principle, an increase in DNA-binding proteins could be important to protect chromosomes from damage, a mechanism noted in D. radiodurans and in tardigrades. However, a positive contribution of this gene expression alteration to IR resistance was not quantified or validated.

An early trial of experimental evolution of radiation resistance

Adapting experimental evolution to determine the mechanisms behind IR resistance, we chose the model organism Escherichia coli. The well-characterized genome and proteome of E. coli makes it well suited for determining the functional implications of any mutations driving IR-resistance that these populations develop during evolution. We set out with the intention of generating E. coli with extremophile levels of radiation resistance through a long-term experimental evolution study. The goal of this work was to broadly discover mechanisms that can contribute to IR resistance.

Our initial evolution trial was initiated nearly 15 years ago, in collaboration with John Battista at Louisiana State University [88]. We started with four replicate E. coli populations, using a 60Co irradiator as our IR source. A selection cycle entails exposure of a population until only 99% are killed, followed by outgrowth of the survivors. Notably, some mutations that might improve IR resistance but cause slower growth would be eliminated in this protocol. After 20 cycles of selection, isolates from each of these populations were sequenced to determine the drivers of IR resistance [14,88,92]. This initial trial revealed that mutations in DNA repair and metabolism genes are clear and early drivers of evolved resistance to IR [14]. Primarily, this work revealed novel variants of RecA (A290S, D276A) that could greatly enhance the IR-resistance of wild-type E. coli [88]. Indeed, two of the four evolved populations had a RecA variant at the same residue (D276N and D276A) in each sequenced isolate, and a third population had a RecA variant (A290S) in most, but not all, of the sequenced isolates [88]. Furthermore, these populations had prominent mutations in two DNA helicases, the replicative helicase DnaB and the putative helicase YfjK, that contributed to major increases in IR resistance [14].

One of the three evolved populations had no mutations in recA. We later determined that IR-resistance in this isolate stemmed in part from a variant of the transcription factor FNR, which controls a significant portion of anaerobic metabolism in E. coli [92]. The presence of an FNR variant was unique to this evolved population. This variant (FNR F186I) decreases FNR functionality. Although the mechanism is unknown, we speculate that this FNR variant decreases the ROS generated by normal aerobic metabolism (a significant source of ROS [27]), therefore freeing ROS-attenuating or DNA/protein repair enzymes to deal with the aftermath of irradiation. Given the severe ROS stress induced by IR, it appeared as though this population had taken a different path to IR resistance: removal of ROS.

Despite advances made in this initial evolution trial, directed evolution of these populations could not be continued. Decay of the 60Co and 137Cs sources used for selection and assays, together with security issues that were forcing decommissioning of many academic irradiators, made it impossible to continue experimental evolution of these populations with any consistency in the selection protocol. We needed to start again.

Rationale and methodology for a new experimental evolution trial

Clinical linear accelerators (Linacs) are commonly used in hospitals for cancer radiotherapy. At the University of Wisconsin-Madison, one Linac housed in the Department of Medical Physics has been appropriated solely for basic research. The Linac generates IR by accelerating electrons, providing an irradiation source that does not decay over time. The Linac thus provides the perfect platform to conduct a long-term evolution experiment under irradiation conditions that can be held constant for periods of many years. The Linac came with an added benefit: the device is capable of delivering a high-energy (6 MeV) electron beam at 72 Gy/minute, a nearly fourfold higher dose rate than that used in the previous evolution experiment.

We again started with four replicate populations of E. coli MG1655. Whereas the first evolution trial ended after 20 cycles of selection, the new initiative has been carried through more than 150 cycles of selection to date. Progress reports have been published at rounds 50 [86] and 100 [87] of selection (summarized in the following text).

A collaboration with the Joint Genome Institute of the Department of Energy has been especially important in this second evolution trial because it allowed us to follow individual mutations as they appeared in the populations via deep sequencing of all four populations at every other selection cycle.

Trends in experimental evolution of IR resistance

Over 100 cycles of selection, the dose needed to kill 99% of these E. coli lineages has increased from 750 Gy at the beginning of the experiment to approximately 3000 Gy. It has subsequently continued to increase. The rate of fitness increase was somewhat greater in the early stages of the study, with some of the early genetic changes providing easily measurable benefit. This experiment differs from the long-term evolution trials carried out by Lenski and colleagues [93] in that the selection challenge is adjusted at each stage such that populations are always irradiated at a dose that kills ∼99% of the cells. As populations display higher levels of resistance, they are irradiated with higher doses of IR. No upper limit to the IR resistance of E. coli is yet in sight.

Mutations thus far shown to enhance IR resistance are summarized in Table 2, Key table. Some general trends are evident (Figure 1, Key figure). Contributing mutations appearing early were concentrated in genes related to DNA repair. Aside from loss of the e14 prophage, we only observed a single mutation in common between the new and old evolution trials: a variant of DNA recombinase RecA, A290S.

Table 2. Key table.

| Pathway | Protein | Variant | Function | Other variants detected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA repair | DNA helicase/replication | DnaB | P80Hb | Unknown | H29Ye, L74Se, P199Qb, S315Ye, N398Kb |

| YfjK | A152Db | Loss of functionb | I43Te, I172Lb, K294Eb, T317Se, Q484*e, H652Yb, Y714*e | ||

| DSB repair | RecA | D276Nb | Faster filament formation, more efficient DNA strand exchange, less inhibited by ADPf | E19Kd, E286Gd, Y294Cd, E297Ge | |

| D276Aa | |||||

| A290Sa,d | Unknown | ||||

| RecD | A90Ed, S92Id, L223*d, A550Ed, T568Ad | Loss of functiond; hyper-recombination phenotypeg | A39Gd, S43Ge, C71fsd, L85Fe, G94Ve, P99*d, C103*d, N124Dd, L188*d, A271Ed, L286*e, L301Md, G307Wd, G362Ge, Q463*d, L490fse, W534Rd, V560fse | ||

| RecN | K429Qd, R102Pd, E271Gd, A361Td, R368Hd, | Unknown; often linked with RecD variantd | R118Ld, F144Ld, F207Se, S220Ie, R285Cd, S310Ld, E320Ke, S382Rd, R415Le, K450Ee, A512Te | ||

| SSB repair | RecJ | *578L e | Unknown | V1Le, T15Ae, R254Ce, R273Se, S301Ye, I332Ve, Q337Re, M360Ie, F426Le, T454Ne, G502De, K518Me | |

| Transcription | Anaerobic metabolism | Fnr | F186Ic | Decreased activation of FNR-controlled genes, enhances growthc | M157*b |

| RNAP β subunit | RpoB | S72N d | Unknown; similar to stringent RNAP variantsg | F15Ld, D33Ge, V146Fe, R151He, S391Pd, P535Ld, 557Ce, S574Fd, T600Id, V630Ee, D842Ee, Y872Ce, K941Ie, K1200Ee | |

| RNAP subunit | RpoC | K1172I d | Unknown | G125Ce, R202Ce, L268Pe, R271Le, F668Le, Q867Ke, F892Ve, T1328Ae | |

| Aerobic metabolism | ATP synthase α subunit | AtpA | F19L e | Unknown | R101Le, D199De |

| Glycerol 3’ phosphate dehydrogenase | GlpD | V255Mb | Unknown | A34Ge, V239Ee, R395He, R461Ce, L489Qe | |

| ROS response | Glutathione transporter subunit | GsiB | N104Sb | Loss of functionb | A120Ve, D197Ee, F240fse, A241Ge, Q268*e, L288Pb, V480Ab |

| SoxR regulator subunit | RsxB | K121Eb | Unknown | S65Ne, W174*e | |

| Fe-S cluster repair | SufD | V94A e | Unknown | N59Ke, S60Ce, D90Ye, A201Se, M337Ie, E399*e | |

| Amino acid metabolism/polyamine synthesis | CadA | P18F e | Unknown | A114Ve, A407Ve, D487Ye, L547Pe | |

| Capsule biosynthesis | WcaK | Y132Cb | Loss of functionb | P53Te, H176Ne, E184fse, R293Se, M343Ie | |

| Prophage | e14 | Excisiona | Unknown | N/A | |

Sources:

Harris et al. 2009 [88];

Byrne et al. 2014 [14];

Bruckbauer et al. 2019a [86];

Bruckbauer et al. 2019b [92];

Bruckbauer et al. 2020a [87];

Piechura et al. 2014 [109];

Sivaramakrishnan et al. 2017 [94].

Mutations identified from our initial evolution trial using the 60Co gamma-ray source are identified in black font. Mutations identified from the ongoing evolution trial after rounds 50 and 100 of evolution are highlighted in red or blue font, respectively.

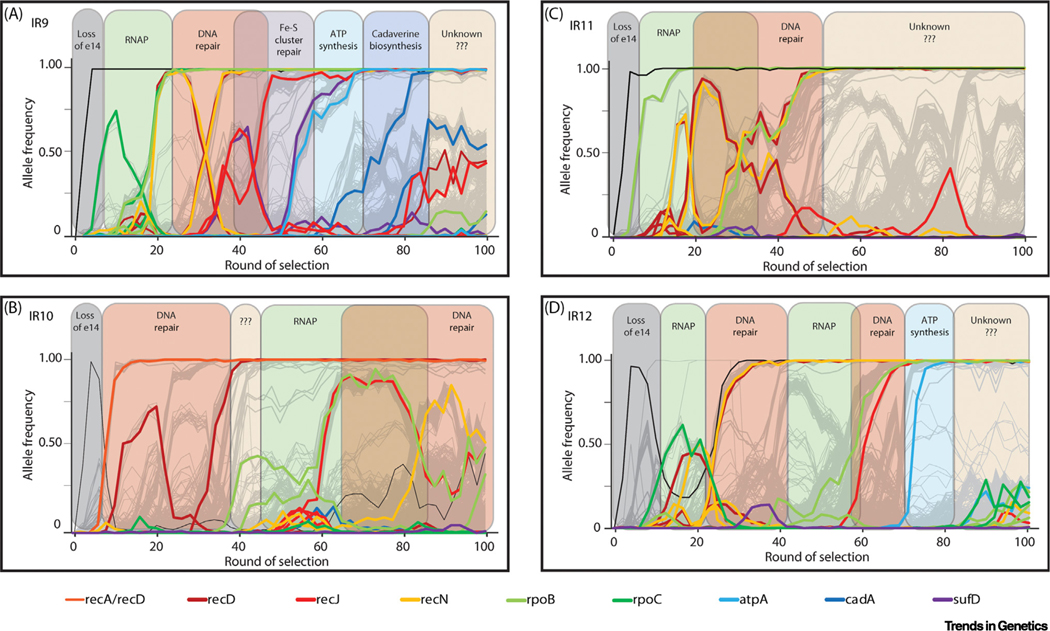

Figure 1. Key figure.

Trends in experimental evolution of ionizing radiation (IR) resistance in Escherichia coli

(A) Loss of the e14 prophage, and mutations affecting RNA polymerase (RNAP), DNA repair, Fe-S cluster repair, ATP synthesis, and cadaverine biosynthesis, have all been confirmed to enhance IR resistance in lineage IR9 [86–88]. Where applicable, these general pathways to IR resistance have been highlighted in the evolving lineages (B) IR10, (C) IR11, and (D) IR12. In general, mutations affecting RNAP and DNA repair are common to all four lineages, especially before round 50 of selection. Since that point, genetic parallelism has given way to significant clonal interference and lineage-specific mechanisms of adaptation (e.g., a major variant of SufD and CadA in IR9 but in no other lineage). In each evolving lineage there are sweeps driven by currently unknown factors.

Aside from RecA, we observed that numerous mutations optimizing DNA repair mechanisms drove the majority of evolved IR resistance over the first 50 cycles of selection (largely isolated from lineage IR9) [86] (Figure 1). Many of these variants lie in the β/β′ subunits of RNA polymerase (RpoB or RpoC). Recent work by Sivaramakrishnan et al. demonstrated that loss of the transcription factor GreA can enhance DSB repair, possibly by utilizing enhanced RecA protein loading by backtracked RNA polymerases [94]. The RpoB and RpoC variants we have picked up in the evolution trial may act by a similar mechanism or may simply be easier to displace during double-strand end resection. Additional mutations occurring early in the evolution trials include null variants of RecD, part of the RecBCD exonuclease/helicase, and alterations to RecN, a cohesin-like protein involved in DSB repair [95]. The RecN and RecD variants often appeared side by side, suggesting epistasis between RecD knockout and altered RecN function. However, no function has been ascribed to these RecN variants. Shortly after round 50 of selection, variants of the exonuclease RecJ became prominent in the evolved populations, suggesting even further modification of DNA repair [87]. All these mutations demonstrably contribute to IR resistance [86,87], indicating that adaptation of the DSB repair system is major path to IR resistance. The results also reinforce the idea that the DSBs introduced by IR are lethal and that their repair is a key prerequisite to survival upon IR exposure.

Over rounds 50–100, the evolving populations diverged from their broadly parallel evolutionary trajectories (Figure 1). The appearance of long-term competition of subpopulations within three of the four lineages (clonal interference) expands the genetic space in which the evolving E. coli can explore new fitness peaks. In lineage IR9 new mutations affecting broad aspects of metabolism [through ATP (atpA) and cadaverine (cadA) synthesis, and repair of Fe-S clusters (sufD)] have further enhanced resistance. Despite identifying eight protein variants which enhanced resistance, we could not fully recapitulate the radioresistant phenotype of an isolate from IR9–100 when placing all eight variants in an otherwise wild-type background [87]. Although the altered biochemistry underlying the contributions of some of these mutations to IR resistance is not yet known, each has the potential to address an obvious IR vulnerability. We speculate that mutations in atpA could reduce the generation of ROS during respiration, therefore increasing the capacity of the cell to deal with ROS, and the downstream oxidative damage, caused by IR. This IR-resistance mechanism may be similar to that conferred by the previously mentioned FNR variant. Alteration of cadA might alter packaging of DNA by polyamines to either enhance DSB repair or prevent closely spaced SSBs from becoming DSBs by stabilizing strand pairing over short regions. Polyamines have previously been implicated to have a role in IR resistance [96]. Mutations to sufD might enhance the repair of Fe-S centers, a primary target of peroxide oxidation [27,28,30].

In general, both evolution experiments agree that modification of DNA repair proteins is a clear initial step to enhance radioresistance of E. coli (either through mutation of RecA, DnaB, and YfjK, or RecD, RecN, and RecJ). As we have previously explored, the evolved populations appear to be diverging in their mechanisms of IR resistance after optimizing DNA repair [87]. Further evolution will shed light on what additional adaptations can enhance radioresistance of E. coli.

Aside from point mutations, the genomes of these evolving E. coli have begun to exhibit larger alterations. We have observed three major genome structural changes: (i) loss of the e14 prophage, (ii) a >100 kb deletion on the left replichore, immediately upstream of the chromosomal terminus, and (iii) a ∼65 kb inverted duplication adjacent to the 100 kb deletion event. Deletion of the e14 prophage was noted in all four populations in our previous evolution trial, and was shown to enhance IR resistance [88]. We do not have a mechanistic explanation for the effects of e14 deletion on IR survival. Loss of the e14 prophage appears to be a common event in experimental evolution of E. coli using other types of selection [97–100], and it is unclear why this prophage is typically maintained in the E. coli genome. The location of e14 is worth noting because it is integrated into the 3′ end of the gene encoding isocitrate dehydrogenase (icd), an essential gene in E. coli. e14 encodes a variant 154 nt sequence to complete icd (without introducing non-synonymous mutations). However, the wild-type icd gene is restored with e14 excision [101].

A large deletion event occurred in two lineages (IR9 and IR10), with one end originating at the same insertion sequence (IS) element (insD1 at approximately nt 1 468 000). Large deletions at this same chromosomal locus have been observed previously in a mutation accumulation line of E. coli developed by Patricia Foster and colleagues [102], suggesting that this area is a hotspot for such events and that these deletions are likely IS element-mediated [103]. Genomic deletions and duplications caused by IS transposition have also been observed in the Lenski long-term evolution experiment [93].

The inverted duplication, which appears in tandem with the ∼120 kb deletion in IR9, is, to our knowledge, a previously unobserved event. Given that the duplication replaces the insD1 gene involved in the IR9 and IR10 deletion events with a different copy of insD1, it is likely that the duplication was also IS-mediated. This duplication effectively creates an additional copy of the dif element, which is involved in resolving chromosomal dimers at the termination of genome replication. It is not yet clear what effect, if any, this duplication (coupled to the significantly shorter left arm of the E. coli chromosome) has on DNA replication.

Owing to the mutagenicity of IR, isolates from these populations are heavily mutated, and at selection round 100 contain ∼400–800 single-base substitutions, insertions, and deletions. Single-base substitutions are the most common mutation event observed, followed by −1 deletions. Deletions of this type are a hallmark of DNA repair by translesion synthesis (TLS) mediated by the mutagenic DNA polymerase IV (DinB) [104,105]. Mutations have accumulated at a relatively steady rate, suggesting that a classical mutator phenotype has not been developed [86,87]. However, a sharp increase in mutation accumulation has been observed recently in IR12; further sequencing data will elucidate whether this represents a sustained change.

Base substitutions appear to be mediated primarily by base oxidation products, consistent with the severe ROS stress induced by IR. The most numerous individual base substitutions are G:C>A:T transitions which are mediated by oxidation-induced cytosine deamination to uracil, leading to mispairing with adenine [5,106]. The next most prominent base substitutions are G:C>T:A transversions and A:T>G:C transitions, likely caused by oxidation of guanine to 8-oxoG, which mispairs with adenine, and deamination of adenine to hypoxanthine, which mispairs with cytosine, respectively [5,106]. In total, there is a ∼50:50 transition to transversion ratio in these populations.

Interestingly, this ratio does not agree with the mutational spectrum observed in E. coli treated with gamma rays [88,107]. In our previous evolution trial we observed an 83:17 transition to transversion bias [88]. This appears to be due to markedly more G:C>T:A transversion mutations in the electron beam-evolved lineages, perhaps due to increased 8-oxoG production (Figure 2). It is unclear whether this difference in mutation spectrum is due to irradiation conditions or whether this is due a difference in the type of damage caused by a high-energy electron beam versus gamma rays.

Figure 2.

Radioresistant E. coli generated in separate evolution experiments exhibit different mutation spectra. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms appear at different frequencies in radioresistant E. coli isolates selected for using a Linac electron beam (IR isolates) [87] compared to those generated with a 60Co gamma-ray source (CB isolates) [14]. Transversion mutations (i.e., purine to pyrimidine) are more common in the isolates exposed to electron-beam ionizing radiation.

Concluding remarks

In the natural world and in the laboratory, we are beginning to learn more about how organisms can survive high levels of IR exposure. We can offer four takeaways from research carried out to date: First, most cases of extremophile levels of IR resistance observed in nature probably arose as an adaptation to desiccation. Some exceptions to this rule may be expected, in the form of (i) organisms that evolved in the presence of low-level but chronic radiation sources, and (ii) newly isolated organisms derived from environments such as that surrounding Chernobyl. Second, proteins involved in DNA metabolism play a key role in IR resistance. These include proteins that protect DNA ends or single-stranded gaps from nuclease degradation, and enzymes that enhance DSB repair. The first group limits the damage. Third, attenuation of the effects of reactive oxygen species is also important. This can take many forms, including (but probably not limited to) ROS scavenging by Mn ions and other processes, enhancement of processes that repair Fe-S centers, and adjustments to decrease the cellular generation of ROS during respiration. Finally, experimental evolution of IR resistance, as an approach to this problem, is ripe for discovery. This research strategy is uniquely positioned to reveal biological strategies for IR resistance that may not exist in any living organism. Within our own trial, only one of four evolved lineages has been characterized in any depth, and all indications are that these populations are diverging in their mechanisms of IR resistance.

As unbiased as it is, this one evolution experiment, by itself, is unlikely to provide a comprehensive view of the mechanisms of IR resistance (see Outstanding questions). Previous work has already shown that surviving chronic exposure to low-dose IR likely requires different mechanisms of resistance than exposure to the acute, high-dose IR that we are using [108]. Indeed, some E. coli isolates evolved to resist acute IR have exhibited variable resistance to chronic IR [42]. In addition, evolution trials with more radiosensitive bacteria (e.g., Shewanella oneidensis) may uncover different pathways for surviving IR exposure. New evolution experiments could be carried out with microorganisms in different kingdoms of life, further expanding our understanding of evolved IR resistance.

Outstanding questions.

How radiation-resistant can an organism become? What is the upper limit to biological radioresistance?

With an optimized DNA repair system, what adaptations drive further increases in radiation resistance?

Are adaptations to DNA repair always the most expedient path to developing resistance to IR?

What is the molecular basis of the DNA repair enhancements in IR-resistant cells?

What constitutes a complete suite of adaptations that are necessary to render an organism resistant to IR at extremophile levels?

Are there multiple paths to extremophile levels of resistance to IR?

In the 75 years since the initial experiments from Evelyn Witkin, several laboratories have made progress towards isolating, evolving, and characterizing IR-resistant organisms. As the field continues to advance, researchers will determine whether the most expedient path to confer IR resistance is (i) genetic [14,87,88], for example by incorporating alterations in the DSB repair pathway; (ii) through the production of IR-protective agents [70,72,73]; or perhaps (iii) through the growth of cocultures of cooperating IR-resistant and IR-sensitive organisms [108]. New discoveries on how organisms can adapt to one of the most extreme stressors known, IR, are likely.

Highlights.

Heritable resistance to IR has been generated numerous times both in nature and in the laboratory through cycles of experimental evolution.

Recent advances in the ‘omics’ era of sequencing technologies are allowing, for the first time, for the genetic basis of evolved IR resistance to be elucidated.

During experimental evolution, modifications to DNA repair mechanisms are the initial drivers of adaptation to extreme doses of IR.

Much remains unknown about both natural and experimentally evolved radioresistance.

Acknowledgements

Work in the laboratory of the authors described here was supported by grant GM112757 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Glossary

- Archaea

one of the three kingdoms of life. First recognized in the 1970s, the Archaea comprise microbes with eukaryote- and bacteria-like properties

- Background radiation

the total dose of radiation experienced in a given environment from natural sources such as radioactive isotopes and cosmic irradiation

- Clonal interference

in an asexual population, clones (derived from the same parent organism) may separately acquire different genotypes and compete. If they have similar fitness, they will prevent each other from sweeping through the population.

- Chernobyl

refers to the Chernobyl nuclear disaster of 1986 which resulted in severe irradiation of the surrounding area

- Desiccation

stress induced by severe lack of intracellular water; also known as ‘xeric stress’ and ‘drying’

- Driver

a characteristic (here, a mutation) which is the basis for an increase in fitness of the organism in question over its competitors

- Extremophile

an organism with optimal growth conditions in, or that can survive exposure to, an environmental feature that is lethal to most life

- Fenton chemistry

the perpetuation of ROS through cyclic reactions of Fe atoms with hydrogen peroxide

- Fe-S cluster

highly oxidation-sensitive cofactors consisting of one or more Fe atoms coordinated by the sulfur of cysteine side-chains in a folded protein

- Gray (Gy)

a unit describing the absorbed dose of radiation, defined as one joule of radiation per kg of matter; 1 Gy = 100 rad

- Halophilic

the state of being a halophile, where the organism grows optimally in or can withstand salt concentrations beyond those tolerated by most lifeforms

- Melanin

a multi-ringed compound conferring pigmentation and photoprotection

- Polyploid

an organism which maintains more than two homologous chromosomes per cell

- Prophage

a bacteriophage which has integrated into the host genome; prophages have often lost the ability to productively excise, replicate, and infect new hosts.

- Radiotropism

a preference for environments with relatively high levels of radiation, likely for metabolic purposes

- Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

oxygen-based molecules which may oxidize less-reactive molecules with varying specificity, and are a common source of oxidative stress. Prominent examples are short-lived hydroxyl radicals and superoxide ions, and longer-lived hydrogen peroxide

- Sweep

when a genotype within a mixed population rises to a frequency of 100%, thus becoming the new genetic background of the population

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Witkin EM (1946) A case of inherited resistance to radiation in bacteria. Genetics 31, 236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witkin EM (1946) inherited differences in sensitivity to radiation in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 32, 59–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daly MJ (2009) A new perspective on radiation resistance based on Deinococcus radiodurans. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 7, 237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox MM and Battista JR (2005) Deinococcus radiodurans – the consummate survivor. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 3, 882–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reisz JA et al. (2014) Effects of ionizing radiation on biological molecules-mechanisms of damage and emerging methods of detection. Antiox. Redox Signal 21, 260–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riley PA (1994) Free radicals in biology – oxidative stress and the effects of ionizing radiation. Int. J. Rad. Biol 65, 27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao GZ et al. (2015) Effects of X-ray and carbon ion beam irradiation on membrane permeability and integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. J. Rad. Res 56, 294–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krisko A. and Radman M. (2010) Protein damage and death by radiation in Escherichia coli and Deinococcus radiodurans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107, 14373–14377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daly MJ (2012) Death by protein damage in irradiated cells. DNA Repair 11, 12–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruckbauer ST et al. (2020) Ionizing radiation-induced proteomic oxidation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Cell. Proteom 19, 1375–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang RL et al. (2020) Protein structure, amino acid composition and sequence determine proteome vulnerability to oxidation-induced damage. EMBO J. 39, e104523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruckbauer ST et al. (2021) Proteome damage inflicted by ionizing radiation: advancing a theme in the research of Miroslav Radman. Cells 10, 954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zahradka K. et al. (2006) Reassembly of shattered chromosomes in Deinococcus radiodurans. Nature 443, 569–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrne RT et al. (2014) Evolution of extreme resistance to ionizing radiation via genetic adaptation of DNA repair. eLife 3, e01322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrne RT et al. (2014) Surviving extreme exposure to ionizing radiation: Escherichia coli genes and pathways. J. Bacteriol 196, 3534–3545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu GH and Chance MR (2007) Hydroxyl radical-mediated modification of proteins as probes for structural proteomics. Chem. Rev 107, 3514–3543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kempner ES (2001) Effects of high-energy electrons and gamma rays directly on protein molecules. J. Pharm. Sci 90, 1637–1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minkoff BB et al. (2019) Covalent modification of amino acids and peptides Induced by ionizing radiation from an electron beam linear accelerator used in radiotherapy. Radiat. Res 191, 447–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alizadeh E. et al. (2013) Radiation damage to DNA: the indirect effect of low-energy electrons. J. Phys. Chem Lett. 4, 820–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leichert LI et al. (2008) Quantifying changes in the thiol redox proteome upon oxidative stress in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 8197–8202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hildebrandt T. et al. (2015) Cytosolic thiol switches regulating basic cellular functions: GAPDH as an information hub? Biol. Chem 396, 523–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leichert LI and Dick TP (2015) Incidence and physiological relevance of protein thiol switches. Biol. Chem 396, 389–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peralta D. et al. (2015) A proton relay enhances H2O2 sensitivity of GAPDH to facilitate metabolic adaptation. Nat. Chem. Biol 11, 156–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferreira E. et al. (2015) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is required for efficient repair of cytotoxic DNA lesions in Escherichia coli. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 60, 202–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang NR et al. (2009) Oxidative modifications of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase play a key role in its multiple cellular functions. Biochem. J 423, 253–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu MZ and Imlay JA (2013) Superoxide poisons mononuclear iron enzymes by causing mismetallation. Mol. Microbiol 89, 123–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imlay JA (2013) The molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of oxidative stress: lessons from a model bacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 11, 443–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jang SJ and Imlay JA (2007) Micromolar intracellular hydrogen peroxide disrupts metabolism by damaging iron-sulfur enzymes. J. Biol. Chem 282, 929–937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin ,JE et al. (2015) The Escherichia coli small protein MntS and exporter MntP optimize the intracellular concentration of manganese. Plos Genet . 11, e1004977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobota JM and Imlay JA (2011) Iron enzyme ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase in Escherichia coli is rapidly damaged by hydrogen peroxide but can be protected by manganese. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108, 5402–5407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mole RH (1984) The LD50 for uniform low LET irradiation of man. Br. J. Radiol 57, 355–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin SG et al. (1992) Estimation of median human lethal radiation dose computed from data on occupants of reinforced concrete structures in Nagasaki, Japan. Health Phys 63, 522–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh OV and Gabani P. (2011) Extremophiles: radiation resistance microbial reserves and therapeutic implications. J. Appl. Microbiol 110, 851–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horikawa DD et al. (2006) Radiation tolerance in the tardigrade Milnesium tardigradum. Int. J. Rad. Biol 82, 843–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jonsson KI et al. (2005) Radiation tolerance in the eutardigrade Richtersius coronifer. Int. J. Rad. Biol 81, 649–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashimoto T. et al. (2016) Extremotolerant tardigrade genome and improved radiotolerance of human cultured cells by tardigrade-unique protein. Nat. Commun 7, 12808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamilari M. et al. (2019) Comparative transcriptomics suggest unique molecular adaptations within tardigrade lineages. BMC Genomics 20, 607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chavez C. et al. (2019) The tardigrade damage suppressor protein binds to nucleosomes and protects DNA from hydroxyl radicals. Elife 8, e47682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boothby TC et al. (2017) Tardigrades use intrinsically disordered proteins to survive desiccation. Mol. Cell 65, 975–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dadachova E. and Casadevall A. (2008) Ionizing radiation: how fungi cope, adapt, and exploit with the help of melanin. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 11, 525–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pacelli C. et al. (2017) Melanin is effective in protecting fast and slow growing fungi from various types of ionizing radiation. Environ. Microbiol 19, 1612–1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shuryak I. et al. (2017) Microbial cells can cooperate to resist high-level chronic ionizing radiation. PLoS One 12, e0189261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saleh YG et al. (1988) Resistance of some common fungi to gamma irradiation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 54, 2134–2135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romsdahl J. et al. (2020) Adaptive evolution of a melanized fungus reveals robust augmentation of radiation resistance by abrogating non-homologous end-joining. Environ. Microbiol 23 Published online October 19, 2020. 10.1111/1462-2920.15285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kottemann M. et al. (2005) Physiological responses of the halophilic archaeon Halobacterium sp strain NRC1 to desiccation and gamma irradiation. Extremophiles 9, 219–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hildenbrand C. et al. (2011) Genome copy numbers and gene conversion in methanogenic archaea. J. Bacteriol 193, 734–743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baliga NS et al. (2004) Systems level insights into the stress response to UV radiation in the halophilic archaeon Halobacterium NRC-1. Genome Res. 14, 1025–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pedone E. et al. (2004) Sensing and adapting to environmental stress: the Archaeal tactic. Front. Biosci 9, 2909–2926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stan-Lotter H. and Fendrihan S. (2015) Halophilic Archaea: life with desiccation, radiation and oligotrophy over geological times. Life (Basel) 5, 1487–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fendrihan S. et al. (2006) Extremely halophilic archaea and the issue of long-term microbial survival. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol 5, 203–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGenity TJ et al. (2000) Origins of halophilic microorganisms in ancient salt deposits. Environ. Microbiol 2, 243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park JS et al. (2009) Haloarchaeal diversity in 23, 121 and 419 MYA salts. Geobiology 7, 515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson AW et al. (1956) Studies on a radio-resistant Micrococcus. I. Isolation, morphology, cultural characteristics, and resistance to gamma radiation. Food Technol. 10, 575–578 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rainey FA et al. (2005) Extensive diversity of ionizing-radiation-resistant bacteria recovered from Sonoran Desert soil and description of nine new species of the genus Deinococcus obtained from a single soil sample. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 71, 5225–5235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Groot A. et al. (2005) Deinococcus deserti sp. nov., a gamma-radiation-tolerant bacterium isolated from the Sahara Desert. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 55, 2441–2446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun J. et al. (2009) Isolation and identification of a new radiation-resistant bacterium Deinococcus guangriensis sp. nov. and analysis of its radioresistant character. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 49, 918–924 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Groot A. et al. (2009) Alliance of proteomics and genomics to unravel the specificities of Sahara bacterium Deinococcus deserti. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lim S. et al. (2019) Conservation and diversity of radiation and oxidative stress resistance mechanisms in Deinococcus species. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 43, 19–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Slade D. and Radman M. (2011) Oxidative stress resistance in Deinococcus radiodurans. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 75, 133–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bentchikou E. et al. (2009) A major role of the RecFOR pathway in DNA double-strand-break repair through ESDSA in Deinococcus radiodurans. PLoS Genet. 6, e1000774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morimatsu K. et al. (2012) RecFOR proteins target RecA protein to a DNA gap with either DNA or RNA at the 5′ terminus: implication for repair of stalled replication forks. J. Biol. Chem 287, 35621–35630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Henrikus SS et al. (2019) RecFOR epistasis group: RecF and RecO have distinct localizations and functions in Escherichia coli. Nuc. Acids Res 47, 2946–2965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tanaka M. et al. (2004) Analysis of Deinococcus radiodurans’s transcriptional response to ionizing radiation and desiccation reveals novel proteins that contribute to extreme radioresistance. Genetics 168, 21–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harris DR et al. (2004) Preserving genome integrity: the DdrA protein of Deinococcus radiodurans R1. PLoS Biol. 2, e304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Narumi I. et al. (2004) PprA: a novel protein from Deinococcus radiodurans that stimulates DNA ligation. Mol. Microbiol 54, 278–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dulermo R. et al. (2015) Identification of new genes contributing to the extreme radioresistance of Deinococcus radiodurans using a Tn5-based transposon mutant library. PLoS One 10, e0124358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Earl AM et al. (2002) The IrrE protein of Deinococcus radiodurans R1 is a novel regulator of recA expression. J. Bacteriol 184, 6216–6224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Daly MJ et al. (2004) Accumulation of Mn(II) in Deinococcus radiodurans facilitates gamma-radiation resistance. Science 306, 1025–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sharma A. et al. (2017) Across the tree of life, radiation resistance is governed by antioxidant Mn2+, gauged by paramagnetic resonance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 114, E9253–E9260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Daly MJ et al. (2010) Small-molecule antioxidant proteome – shields in Deinococcus radiodurans. PLoS One 5, e12570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Granger AC et al. (2011) Effects of Mn and Fe levels on Bacillus subtilis spore resistance and effects of Mn2+, other divalent cations, orthophosphate, and dipicolinic acid on protein resistance to ionizing radiation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 77, 32–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gupta P. et al. (2016) MDP: a Deinococcus Mn2+– decapeptide complex protects mice from ionizing radiation. PLoS One 11, e0160575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gaidamakova EK et al. (2012) Preserving immunogenicity of lethally irradiated viral and bacterial vaccine epitopes using a radio-protective Mn2+–peptide complex from Deinococcus. Cell Host Microbe 12, 117–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang YM et al. (2006) Characterization of a Mn-dependent fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase in Deinococcus radiodurans. Biometals 19, 31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sun H. et al. (2010) Identification and evaluation of the role of the manganese efflux protein in Deinococcus radiodurans. BMC Microbiol. 10, 319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Karam PA and Leslie SA (1999) Calculations of background beta-gamma radiation dose through geologic time. Health Phys. 77, 662–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Franca MB et al. (2007) Oxidative stress and its effects during dehydration. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol 146, 621–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dartnell LR et al. (2010) Low-temperature ionizing radiation resistance of Deinococcus radiodurans and Antarctic Dry Valley bacteria. Astrobiology 10, 717–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yu LZ et al. (2015) Diversity of ionizing radiation-resistant bacteria obtained from the Taklimakan Desert. J. Basic Microbiol 55, 135–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Potts M. (1994) Desiccation tolerance of prokaryotes. Microbiol. Rev 58, 755–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lebre PH et al. (2017) Xerotolerant bacteria: surviving through a dry spell. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 15, 285–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moller AP and Mousseau TA (2006) Biological consequences of Chernobyl: 20 years on. Trends Ecol. Evol 21, 200–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Davies R. and Sinskey AJ (1973) Radiation-resistant mutants of Salmonella typhimurium LT2: development and characterization. J. Bacteriol 113, 133–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Erdman IE et al. (1961) Studies on the irradiation of microorganisms in relation to food preservation. II. Irradiation resistant mutants. Can. J. Microbiol 7, 207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Parisi A. and Antoine AD (1974) Increased radiation resistance of vegetative Bacillus pumilus. Appl. Microbiol 28, 41–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bruckbauer ST et al. (2019) Experimental evolution of extreme resistance to ionizing radiation in Escherichia coli after 50 cycles of selection. J. Bacteriol 201, e00784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bruckbauer ST et al. (2020) Physiology of highly radioresistant Escherichia coli after experimental evolution for 100 cycles of selection. Front. Microbiol 11, 2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Harris DR et al. (2009) Directed evolution of radiation resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol 191, 5240–5252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brooks BW and Murray RGE (1981) Nomenclature for ‘Micrococcus radiodurans’ and other radiation-resistant cocci: Deinococcaceae fam. nov. and Deinococcus gen. nov., including five species. International J. Syst. Bacteriol 31, 353–360 [Google Scholar]

- 90.van Dijk EL et al. (2018) The third revolution in sequencing technology. Trends Genet. 34, 666–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.DeVeaux LC et al. (2007) Extremely radiation-resistant mutants of a halophilic archaeon with increased single-stranded DNA-binding protein (RPA) gene expression. Radiat. Res 168, 507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bruckbauer ST et al. (2019) A variant of the Escherichia coli anaerobic transcription factor FNR exhibiting diminished promoter activation function enhances ionizing radiation resistance. PLoS One 14, e0199482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tenaillon O. et al. (2016) Tempo and mode of genome evolution in a 50,000-generation experiment. Nature 536, 165–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sivaramakrishnan P. et al. (2017) The transcription fidelity factor GreA impedes DNA break repair. Nature 550, 214–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Uranga LA et al. (2017) The cohesin-like RecN protein stimulates RecA-mediated recombinational repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Commun 8, 15282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Oh TJ and Kim IG (1998) Polyamines protect against DNA strand breaks and aid cell survival against irradiation in Escherichia coli. Biotech. Tech 12, 755–758 [Google Scholar]

- 97.Moreau PL and Loiseau L. (2016) Characterization of acetic acid-detoxifying Escherichia coli evolved under phosphate starvation conditions. Microb. Cell Factories 15, 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Charusanti P. et al. (2010) Genetic basis of growth adaptation of Escherichia coli after deletion of pgi, a major metabolic gene. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang Q. et al. (2014) You cannot tell a book by looking at the cover: cryptic complexity in bacterial evolution. Biomicrofluidics 8, 052004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sekowska A. et al. (2016) Generation of mutation hotspots in ageing bacterial colonies. Sci. Rep 6, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hill CW et al. (1989) Use of the isocitrate dehydrogenase structural gene for attachment of e14 in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol 171, 4083–4084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee H. et al. (2012) Rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in the bacterium Escherichia coli as determined by whole-genome sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, E2774–E2783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lee H. et al. (2016) Insertion sequence-caused large-scale rearrangements in the genome of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 7109–7119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wagner J. and Nohmi T. (2000) Escherichia coli DNA polymerase IV mutator activity: genetic requirements and mutational specificity. J. Bacteriol 182, 4587–4595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kim SR et al. (1997) Multiple pathways for SOS-induced mutagenesis in Escherichia coli: an overexpression of dinB/dinP results in strongly enhancing mutagenesis in the absence of any exogenous treatment to damage DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 94, 13792–13797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang D. et al. (1998) Mutagenicity and repair of oxidative DNA damage: insights from studies using defined lesions. Mutat. Res 400, 99–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Xie C-X et al. (2004) Comparison of base substitutions in response to nitrogen ion implantation and 60Co-gamma ray irradiation in Escherichia coli. Genet. Mol. Biol 27, 284–290 [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shuryak I. et al. (2019) Chronic gamma radiation resistance in fungi correlates with resistance to chromium and elevated temperatures, but not with resistance to acute irradiation. Sci. Rep 9, 11361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Piechura JR et al. (2015) Biochemical characterization of RecA variants that contribute to extreme resistance to ionizing radiation. DNA Repair (Amst) 26, 30–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]