Abstract

The recently discovered Anopheles symbiont, Microsporidia MB, has a strong malaria transmission-blocking phenotype in Anopheles arabiensis, the predominant Anopheles gambiae species complex member in many active transmission areas in eastern Africa. The ability of Microsporidia MB to block Plasmodium transmission together with vertical transmission and avirulence makes it a candidate for the development of a symbiont-based malaria transmission blocking strategy. We investigate the characteristics and efficiencies of Microsporidia MB transmission between An. arabiensis mosquitoes. We show that Microsporidia MB is not transmitted between larvae but is effectively transmitted horizontally between adult mosquitoes. Notably, Microsporidia MB was only found to be transmitted between male and female An. arabiensis, suggesting sexual horizontal transmission. In addition, Microsporidia MB cells were observed infecting the An. arabiensis ejaculatory duct. Female An. arabiensis that acquire Microsporidia MB horizontally are able to transmit the symbiont vertically to their offspring. We also investigate the possibility that Microsporidia MB can infect alternate hosts that live in the same habitats as their An. arabiensis hosts, but find no other non-anopheline hosts. Notably, Microsporidia MB infections were found in another primary malaria African vector, Anopheles funestus s.s. The finding that Microsporidia MB can be transmitted horizontally is relevant for the development of dissemination strategies to control malaria that are based on the targeted release of Microsporidia MB infected Anopheles mosquitoes.

Keywords: symbiosis, Anopheles, malaria, vector, Microsporidia

Importance Statement

The malaria disease burden remains a major impediment to good health and economic development in many regions of sub-Saharan Africa. We have recently reported that a microsporidian symbiont (Microsporidia MB) naturally blocks Plasmodium transmission in Anopheles arabiensis, a major vector of malaria in Africa. Microsporidia MB could form the basis of a novel transmission blocking intervention for malaria control. However, the development of Microsporidia MB as an intervention a strategy will require a better understanding of the symbiont’s biology. Of particular relevance are the natural mosquito to mosquito transmission routes that enable Microsporidia MB to spread within Anopheles mosquito populations and which could potentially be used to disseminate Microsporidia MB as part of a malaria transmission blocking strategy. We investigate the natural routes of Microsporidia MB’s mosquito to mosquito transmission and find that it can be transmitted horizontally between adult An. arabiensis of opposite sexes. This finding will aid the development of a Microsporidia MB dissemination strategy, potentially involving targeted release of Microsporidia MB infected Anopheles mosquitoes.

Introduction

Malaria continues to be a major health threat across sub-Saharan Africa, with this region accounting for 93% of the global malaria deaths (World Health Organization, 2020). The major preventive strategies for malaria control remain the use of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS). In conjunction with improvements in case detection and management, these strategies have reduced malaria cases by up to 40% between 2000 and 2015 (Bhatt et al., 2015). However, progress has plateaued and possibly reversed, with case levels remaining the same between 2014 and 2016 and increasing between 2016 and 2017 (D’Alessandro, 2018; World Health Organization, 2020). It is apparent that current malaria control strategies have their limitations and there is a vital need for complementary tools (Huijben and Paaijmans, 2018).

The malaria transmission cycle relies on female Anopheles mosquitoes becoming infected by feeding on human blood that contains the Plasmodium gametocyte stage. Plasmodium gametocytes undergo a series of developmental changes before traversing the mosquito midgut to form a sporogonic oocyst, which produces sporozoites that are released into the mosquito hemocoel. Sporozoites in the hemocoel travel to the mosquito salivary glands to enter the mosquito’s saliva, which results in an infected mosquito, usually 8–14 days after the bloodmeal (Baton and Ranford-Cartwright, 2005). This transmission cycle can be impeded by inhibitory interactions with mosquito-associated microbes (Romoli and Gendrin, 2018). One of the most promising new management strategies involves the use of vertically (mother to offspring) transmitted symbiotic microbes that prevent the establishment of disease-causing viruses in mosquito vectors. This strategy is currently used as a control mechanism against the arboviral disease, Dengue, through the bacterial symbiont, Wolbachia (Moreira et al., 2009; Bian et al., 2010; Hoffmann et al., 2011; Walker et al., 2011; Frentiu et al., 2014; Ant et al., 2018; Nazni et al., 2019).

The Anopheles-associated symbiont Microsporidia MB colonizes mosquito ovaries and is vertically transmitted. This microsporidian can also block the transmission of malaria by Anopheles mosquitoes (Herren et al., 2020), and therefore could potentially contribute to the control of malaria. The successful deployment of symbiont-based vector-borne disease control strategies requires the ability to spread symbionts through host insect populations and the maintenance of a high prevalence of infection. In Wolbachia-based strategies, cytoplasmic incompatibility can effectively drive symbionts through mosquito populations. In the absence of cytoplasmic incompatibility, other driving mechanisms would be required to spread Microsporidia MB through Anopheles populations. Microsporidia MB is naturally found in populations of Anopheles mosquitoes in Kenya, ranging in prevalence from 0 to 25% (Herren et al., 2020). From the standpoint of symbiont-based control strategies, the different Microsporidia MB transmission routes could be relevant for interventions that could generate a higher prevalence of the transmission-blocking symbiont in Anopheles mosquito populations, leading to reductions in malaria transmission.

Microsporidia are a diverse clade of obligate, intracellular organisms that infect an array of hosts, including vertebrates and invertebrates and are found in both terrestrial and aquatic environments (Vossbrinck and Debrunner-Vossbrinck, 2005). The morphology of Microsporidia can be simplified into the meront phase, which is present during proliferation, and the spore, which is resistant to environmental degradation and transmission-specialized. Microsporidian spores are characterized by a chitinous wall and a polar filament involved in host cell penetration (Stentiford et al., 2013). In arthropods, Microsporidian transmission can occur vertically (mother to offspring) and horizontally (from one individual to another of the same generation, Stentiford et al., 2013). There are also many reported incidences of microsporidians using a combination of vertical and horizontal transmission. Vertical transmission generally occurs via the transovarial route with spores germinating on the periphery or inside of ovaries to colonize developing eggs. Vertical transmission is associated with greater host specificity and lower Microsporidia burden and virulence (Vávra and Lukeš, 2013). There are different forms of horizontal transmission in arthropod-associated Microsporidia, however the most widespread is oral and involves the ingestion of spores, which subsequently germinate and inject their sporoplasm into the host intestinal cells through a polar filament. Microsporidia that predominately rely on oral horizontal transmission tend to be associated with lower levels of host specificity and high virulence as microsporidian spores will usually be released en masse from deceased hosts to infect other hosts (Han and Weiss, 2017). Other forms of horizontal transmission that are not associated with high virulence, for example sexual transmission, have also been demonstrated in several microsporidian species. Nosema plodiae is a microsporidian pathogen of the Indian meal moth, Plodia interpunctella, which invades the reproductive organs of its host and is transmitted from male to female moths during mating (Kellen and Lindegren, 1971).

The Microsporidia transmission mode influences host specificity and life-cycle complexity (Stentiford et al., 2013). Microsporidians can be generalists, infecting a variety of different hosts or exhibit high levels of host specialization. Microsporidians can have specialization toward a single (simple lifecycle) or several intermediate hosts (complex lifecycle). Vertical and sexual transmission result in limited opportunities for Microsporidia to infect hosts of a different species and are therefore likely to lead to higher levels of host specificity. In contrast, horizontal transmission by spore ingestion is likely to be associated with lower levels of host specificity. Microsporidians with simple and complex lifecycles can use both vertical and horizontal transmission. In most cases, different spores types become specialized for different transmission routes (Stentiford et al., 2013).

We investigated a number of possible horizontal transmission routes for Microsporidia MB in An. arabiensis. We established that transmission was only found to occur between adult mosquitoes. In addition, transmission was only observed between different sexes, which indicates that Microsporidia MB is sexually transmitted in An. arabiensis.

Results

Horizontal Transmission of Microsporidia MB Occurs Between Adult An. arabiensis

To determine if Microsporidia MB is horizontally transmitted at the adult or larval stages, Microsporidia MB infected and uninfected larvae and mosquitoes were housed together in larval rearing troughs or cages. Since it is difficult to reliably mark or determine the sex of larvae, we placed infected and uninfected larvae in two adjacent sections of rearing trough that was separated by a screen mesh. For larval experiments a roughly equal number of infected donor and uninfected recipient L1 larvae (N = 16–35) were placed in mesh separated compartments and allowed to develop into adults. After adults eclosed both donor and recipient specimens were screened for the presence of Microsporidia MB. Under these conditions horizontal transmission of Microsporidia MB was not observed (Figure 1A and Table 1). The addition of homogenized infected larvae to the rearing water of uninfected larvae and to sugar sources given to uninfected adult An. arabiensis also did not result in horizontal transmission of Microsporidia MB (Table 2). Altogether these findings indicate that intact, alive An. arabiensis larvae or the homogenates of Microsporidia MB-infected larvae and adults are not able to transmit Microsporidia MB horizontally to other An. arabiensis individuals (larval or adult).

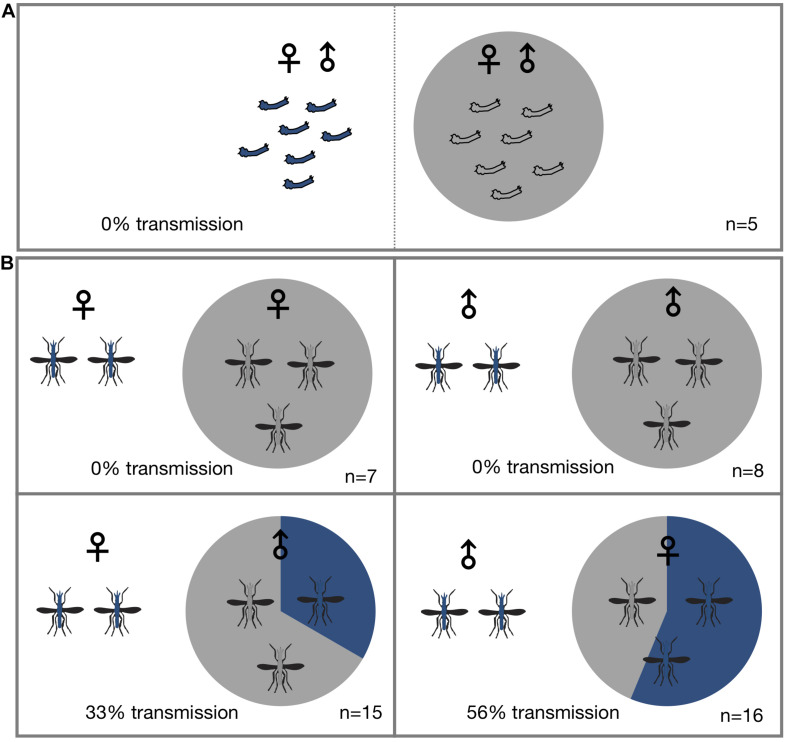

FIGURE 1.

Horizontal transmission of Microsporidia MB. Mosquitoes carrying Microsporidia MB are represented with blue shading in pie charts and n = number of independent experiments. (A) No transmission of Microsporidia MB was observed between An. arabiensis larvae reared in the same larval trough but separated by a screen mesh. (B) Horizontal transmission of Microsporidia MB was observed when adults were kept together in cages, and specifically when either infected males or females were housed with uninfected An. arabiensis of the opposite sex. Top row, no transmission was observed between infected and uninfected individuals of the same sex. Bottom left, transmission between Microsporidia MB infected An. arabiensis females and uninfected males was observed in 5 out of 15 cages (33%). Bottom right, out of a total of 16 experiments that had Microsporidia MB infected males and uninfected females and horizontal transmission was confirmed in 10 of these cages (56% transmission).

TABLE 1.

Horizontal transmission is not observed when An. arabiensis larvae are reared in the same larval trough but separated by a screen mesh.

| Expt # | Number of | Microsporidia MB positives | Number of | Infection prevalence | Transmission |

| (Sheet labels) | donor larvae | in donor larvae | recipient larvae | in donor larvae | rate |

| LL1 | 10 | 8 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| LL3 | 9 | 9 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| LL4 | 14 | 4 | 31 | 0 | 0 |

| LL5 | 20 | 13 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| LL6 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

TABLE 2.

Homogenates from larval and adult Microsporidia MB infected mosquitoes are not able to establish infections after being ingested by An. arabiensis.

| Source of Microsporidia MB inoculum | Target Anopheles stage | Number of experimental repeats | Number of samples per experiment | Microsporidia MB Transmission |

| Homogenized larvae | Larvae (in rearing water) | 3 | 20,14,17 | 0/20, 0/14, and 0/17 |

| Homogenized larvae | Adults (in sugar source) | 4 | 13,16,16 | 0/13, 0/16, and 0/16 |

| Homogenized adults | Adults (in sugar source) | 3 | 31,36,40 | 0/31, 0/36, and 0/40 |

| Homogenized adults | Larvae (in rearing water) | 3 | 28,31,28 | 0/28, 0/31, and 0/28 |

Homogenized infected larvae and adults were fed to adult (in sugar source) and larval (in rearing water) An. arabiensis, to determine if Microsporidia MB could be transmitted horizontally by ingestion. None of the An. arabiensis that fed on Microsporidia MB infected homogenates became infected with Microsporidia MB.

To investigate horizontal transmission of Microsporidia MB between live adults, we established cages with Microsporidia MB infected and uninfected mosquitoes. Adult mosquitoes were maintained in these cages for a period of 2 days before they were screened for the presence of Microsporidia MB. Additionally, to determine if horizontal transmission between mosquitoes could involve sugar sources, these were screened; Microsporidia MB was not detected in sugar sources (Table 3). In cages that had Microsporidia MB infected and uninfected mosquitoes of the same sex, the mosquitoes were marked with dye to indicate Microsporidia MB “donors” and “recipients” prior to exposure. In general, 2–6 infected An. arabiensis were kept together with 10–25 uninfected mosquitoes in standard 30 cm × 30 cm × 30 cm cages. At the end of the experiment all mosquitoes were screened to confirm infection status and determine if horizontal transmission had occurred. Out of 47 cage experiments, horizontal transmission was observed in 15 cage experiments (Figure 1B and Table 4). Notably, horizontal transmission was only observed in cages that had opposite sexes of Microsporidia MB infected and uninfected adult An. arabiensis. Out of 16 cages that had Microsporidia MB infected males and uninfected females, transmission was confirmed in 9 cages (56%). Amongst 15 cages that had Microsporidia MB infected females and uninfected males, transmission was confirmed in 5 cages (33%). In 15 cages that had the same sex Microsporidia MB infected and uninfected adult An. arabiensis, horizontal transmission was not observed. To investigate the link between Microsporidia MB transmission from male An. arabiensis to females and insemination, and to approximate the mating frequency in cage experiments, female An. arabiensis spermatheca were dissected and checked for the presence of sperm (Table 5). The mating frequency in cage experiments where spermatheca were checked (N = 3) was found to range from 0 to 8%. Notably, Microsporidia MB transmission was only recorded in females that had sperm in their spermatheca.

TABLE 3.

Sugar sources fed on by Microsporidia MB infected mosquitoes do not contain detectable levels of Microsporidia MB.

| Experiment ID | Experiment type | Infection status |

| MF4 | Male + /Female − | Not infected |

| MF5 | Male + /Female − | Not infected |

| MF6 | Male + /Female − | Not infected |

| MF7 | Male + /Female − | Not infected |

| MF8 | Male + /Female − | Not infected |

| MF9 | Male + /Female − | Not infected |

| MF10 | Male + /Female − | Not infected |

| FM2 | Female + /Male − | Not infected |

| FM3 | Female + /Male − | Not infected |

| FM4 | Female + /Male − | Not infected |

| MM1 | Male + /Male − | Not infected |

| MM2 | Male + /Male − | Not infected |

| MM3 | Male + /Male − | Not infected |

| MM4 | Male + /Male − | Not infected |

| FF1 | Female + /Female − | Not infected |

| FF2 | Female + /Female − | Not infected |

| FF3 | Female + /Female − | Not infected |

TABLE 4.

Horizontal transmission of Microsporidia MB between adults housed together in cages.

| Expt # (Sheet labels) | Number of donor mates in the cage | Number of confirmed MB+ donor mates in the cage | Total exposed screened | Donor 1 intensity | Donor 2 intensity | Donor 3 intensity | Donor 4 intensity | Donor 5 intensity | Donor 6 intensity | # Recipients acquired Infection | # Recipients didn’t acquire Infection | Recipient 1 intensity | Recipient 2 Intensity | Recipient 3 Intensity | |

| Male to Female | |||||||||||||||

| MF4 | 2 | 1 | 14 | 6.468956 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 13 | 15.67 | |||

| MF5 | 3 | 1 | 14 | 3.950098 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 13 | 0.659 | |||

| MF6 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 1.308167 | 8.4389 | 2.8418 | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 14 | ||||

| MF7 | 2 | 2 | 15 | 12.48482 | 41.056 | 6.1403 | NA | NA | NA | 3 | 12 | 2.041 | 0.8229 | 0.496 | |

| MF8 | 2 | 2 | 19 | 4.897402 | 94.392 | 8.5958 | NA | NA | NA | 3 | 16 | 0.624 | 36.948 | 0.254 | |

| MF9 | 2 | 1 | 14 | 14.75445 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 13 | 173.6 | |||

| MF10 | 2 | 1 | 21 | 0.489231 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 19 | 14.54 | 6.3849 | ||

| MF11 | 2 | 1 | 25 | 1.320645 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 24 | 4.996 | |||

| MF16 | 2 | 1 | 17 | 1.329321 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 17 | ||||

| MF18 | 2 | 1 | 17 | 0.224129 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 17 | ||||

| MF24 | 2 | 1 | 25 | 0.148271 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 25 | ||||

| MF3 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 0.476983 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 13 | ||||

| SPM 212 | 7 | 3 | 33 | 2990.757 | 3.4633 | 449.23 | 7.5334 | 207.08 | NA | 1 | 32 | 354.4 | |||

| SPM 297 | 7 | 1 | 31 | 11.42972 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 31 | ||||

| SPM 304 | 11 | 3 | 37 | 27.86255 | 1.1878 | 16.141 | 1E-05 | 3660 | NA | 2 | 35 | 5.132 | 25.646 | ||

| SPM 315 | 3 | 2 | 17 | 4.047635 | 5.3183 | 2.1773 | N/A | N/A | NA | 0 | 17 | ||||

| Female to Male | |||||||||||||||

| FM2 | 6 | 2 | 20 | 20.15738 | 1.6845 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 20 | ||||

| FM3 | 5 | 1 | 25 | 5.352259 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 25 | ||||

| FM4 | 4 | 1 | 25 | 1.467548 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 30 | ||||

| BDF03 | 11 | 1 | 16 | 13.74596 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 16 | ||||

| BDF47 | 13 | 1 | 14 | 7.607281 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 13 | 0.337 | |||

| BDF53 | 15 | 5 | 13 | 0.45705 | 42.397 | 1.3176 | 4.1668 | 44.417 | NA | 3 | 10 | 0.397 | 1.8002 | 4.485 | |

| BDF64 | 9 | 2 | 19 | 2.01744 | 0.2731 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 17 | 9.998 | 1.1225 | ||

| BDF 77 | 13 | 2 | 21 | 10.08619 | 0.1461 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 21 | ||||

| 318 B | 15 | 6 | 26 | 25.97944 | 14.504 | 9.4598 | 5.8088 | 2.2449 | 7.2807 | 0 | 26 | ||||

| 319A | 10 | 1 | 43 | 173.9875 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 43 | ||||

| 338D | 11 | 4 | 39 | 2.583147 | 4.761 | 2.2513 | 1.1604 | NA | NA | 0 | 39 | ||||

| 339A | 5 | 2 | 19 | 1305.295 | 2.6964 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 18 | 20.43 | |||

| BDF345 | 4 | 1 | 23 | 7.598649 | N/A | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 22 | ||||

| BDF346 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 0.249339 | 11.79 | 6.4213 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 10 | 2.269 | |||

| BDF349 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 1.095105 | 1.2174 | 7.1288 | 27.826 | 50.479 | 1.2548 | 0 | 12 | ||||

| Male to Male | |||||||||||||||

| MM1 | 2 | 1 | 17 | 0.99955 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 17 | ||||

| MM2 | 3 | 1 | 12 | 2.348149 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 12 | ||||

| MM3 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 6.259642 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 15 | ||||

| MM4 | 2 | 1 | 20 | 3.925768 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 20 | ||||

| PPM02 | 2 | 1 | 24 | 2.349105 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 24 | ||||

| PPM08 | 3 | 2 | 31 | 0.516775 | 11.651 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 31 | ||||

| PPM25 | 9 | 1 | 28 | 11.96361 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 28 | ||||

| PPM31 | 13 | 1 | 13 | 9.222971 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 13 | ||||

| Female to Female | |||||||||||||||

| FF1 | 2 | 1 | 13 | 1.62354 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 13 | ||||

| FF2 | 3 | 1 | 25 | 0.21161 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 25 | ||||

| FF3 | 5 | 2 | 16 | 30.35195 | 14.257 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 16 | ||||

| PPF01 | 6 | 5 | 19 | 26.56585 | 21.535 | 57.306 | 302.93 | 51.256 | NA | 0 | 19 | ||||

| PPF07 | 4 | 1 | 21 | 1.339635 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 21 | ||||

| PPF22 | 5 | 1 | 23 | 2.30285 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 23 | ||||

| PPF32 | 7 | 3 | 19 | 0.257489 | 11.032 | 54.376 | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 19 |

Horizontal transmission of Microsporidia MB was observed when either infected males or females were housed with uninfected An. arabiensis of the opposite sex.

TABLE 5.

Microsporidia MB transmission is linked to the presence of sperm in female An. arabiensis spermatheca.

| # of male donors | # of male donors MB+ | # of female recipients | # of female recipients with sperm in spermatheca | # of female recipients sperm+ and MB+ | # of female recipients sperm– and MB+ | |

| SPC12 | 3 | 1 | 25 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| SPC09 | 1 | 1 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SPC15 | 3 | 2 | 59 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

The Success of Microsporidia MB Horizontal Transmission Is Not Linked to Male Infection Intensity

To investigate the factors that influence the rate of Microsporidia MB male to female transmission in An. arabiensis, we established cages with a single Microsporidia MB infected male and 11–48 Microsporidia MB uninfected females. Adult mosquitoes were maintained in these cages for a period of 2 days prior to being screened for the presence and intensity of Microsporidia MB by quantitative PCR. Out of a total of 33 individual An. arabiensis males, 17 were able to infect at least one An. arabiensis female in their cage (51.5%). The highest number of females infected by a single male was 3 females. There was no significant link between male intensity of Microsporidia MB infection and odds of successfully infecting of one or more uninfected females [exp(b) = 0.982, P = 0.715 df = 31]. The number of females per cage did not affect the odds of Microsporidia MB transmission to one or more females [exp(b) = 0.968, P = 0.421 df = 31]. The correlation between the Microsporidia MB infection intensity in donor males and in the female “recipients” was not significantly correlated (R2 = 0, P = 0.34 df = 31) and Supplementary Figure 1). Notably, the average infection intensity in recipient females (10.33) was twice as high as the average infection intensity in male “donors” (5.01).

Microsporidia MB Is Localized to Male An. arabiensis Midgut, Gonads, and Seminal Fluid

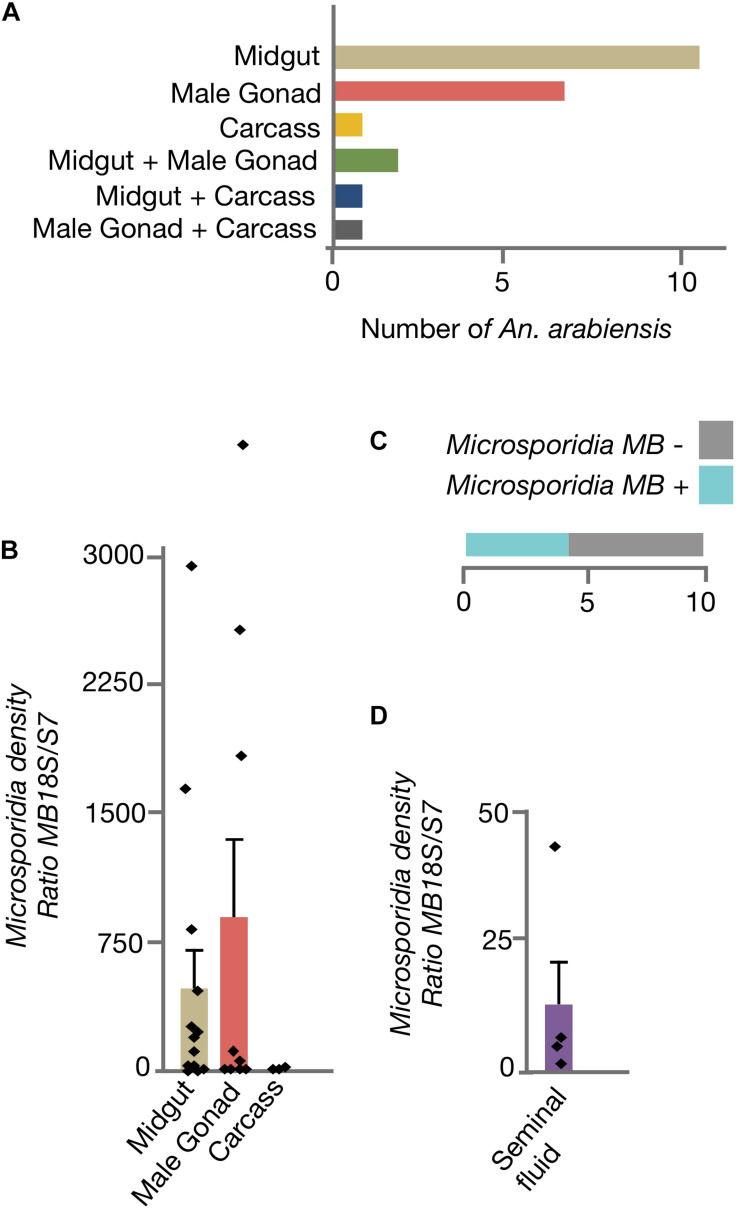

To determine if Microsporidia MB organ distribution in An. arabiensis could be linked to transmission routes, adult males were dissected and Microsporidia MB intensity was quantified in the midgut, male gonads and carcass (Figure 2A). In the majority of male An. arabiensis specimens, Microsporidia MB was detected in the midgut (11/22) or male gonads (7/22). In 2/22 specimens, Microsporidia MB was detected in both the midgut and the male gonads, whereas in only 3/22 specimens could Microsporidia MB be detected in the carcass. In line with these findings, the intensity of Microsporidia MB infections were found to be highest in the An. arabiensis midgut and male gonads and was found to be lower in carcasses (Figure 2B). The collection of seminal fluid from Microsporidia MB infected male An. arabiensis revealed that high intensities of Microsporidia MB could be detected in seminal fluid collected from 4/10 An. arabiensis males (Figures 2C,D).

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of Microsporidia MB across male An. arabiensis organs. (A) The screening dissected organs from 22 male An. arabiensis specimens, reveals that Microsporidia MB is detected primarily in the midguts and male gonads. (B) The intensity of Microsporidia MB infection is highest in the midgut and male gonads. (C) The screening male An. arabiensis seminal fluid revealed that Microsporidia MB was detected in 4/10 specimens. (D) The intensity of Microsporidia MB infection in An. arabiensis seminal fluid ranges from a ratio of 0.87 to 41.8 MB18S/S7. Error bars reflect SEM.

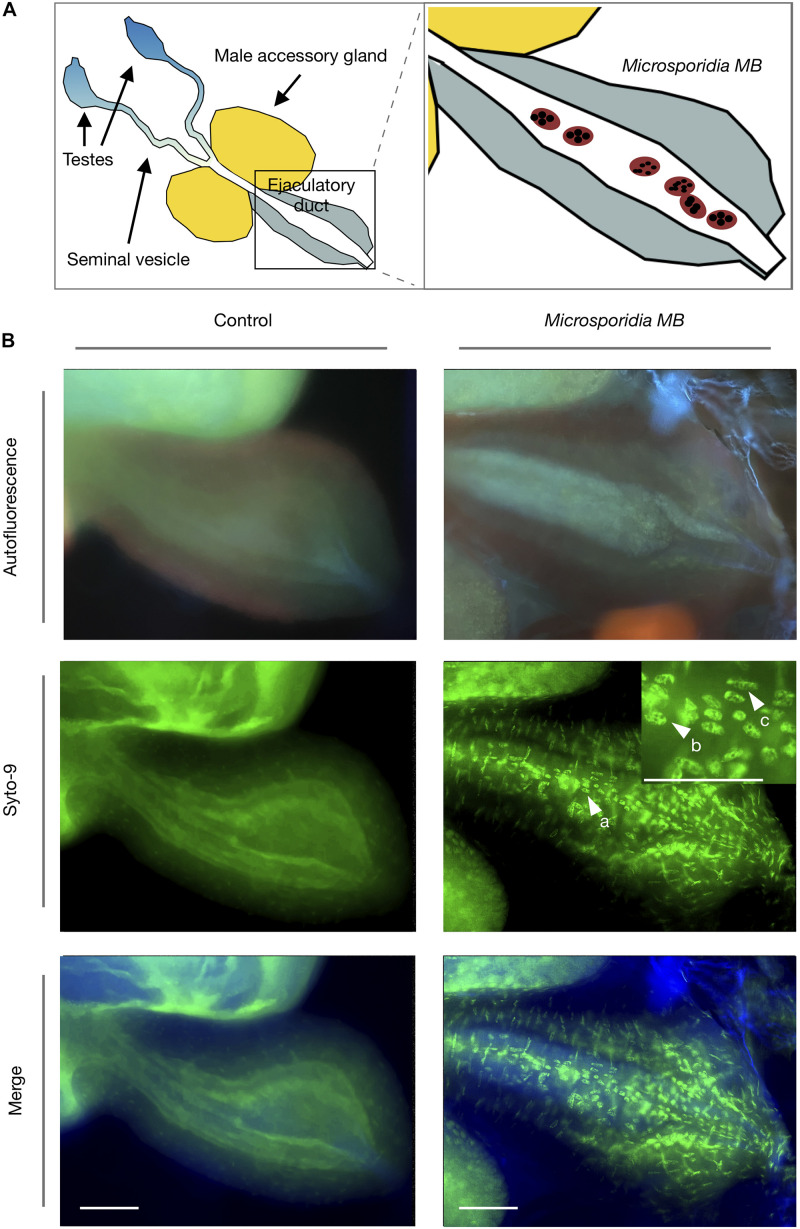

Microsporidia MB Cells Are Present in the An. arabiensis Male Ejaculatory Duct

Fluorescence microscopy of male gonads revealed that Microsporidia MB cells were present in the male ejaculatory duct (Figure 3). Only in Microsporidia MB infected male An. arabiensis were the multinucleated cells corresponding to Microsporidia MB observed. Syto-9 nucleic acid staining revealed that the Microsporidia MB cells generally had either 4 or 8 nuclei, which likely corresponds to the progression on of 4-nuclei sporogonial plasmodia into an 8-nuclei stage (3rd sporogonic nuclear division) and ultimately becoming sporophorous vesicles (Sokolova and Fuxa, 2008).

FIGURE 3.

Fluorescence microscopy of Microsporidia MB in An. arabiensis male ejaculatory ducts. (A) Schematic diagram of the male Anopheles gonad shows the position of the ejaculatory duct in relation to seminal vesicle, male accessory gland and testes. (B) Fluorescence microscopy images indicate that Microsporidia MB meronts (a) are found in the male An. arabiensis ejaculatory duct. Multinucleate Microsporidia MB cells can be observed containing 4 and 8 distinct nuclei (b,c), which likely corresponds to the progression on of 4-nuclei sporogonial plasmodia into the 8-nuclei sporogonial plasmodia and ultimately into sporophorous vesicles. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Microsporidia MB Can Be Transmitted Vertically After Horizontal Transmission

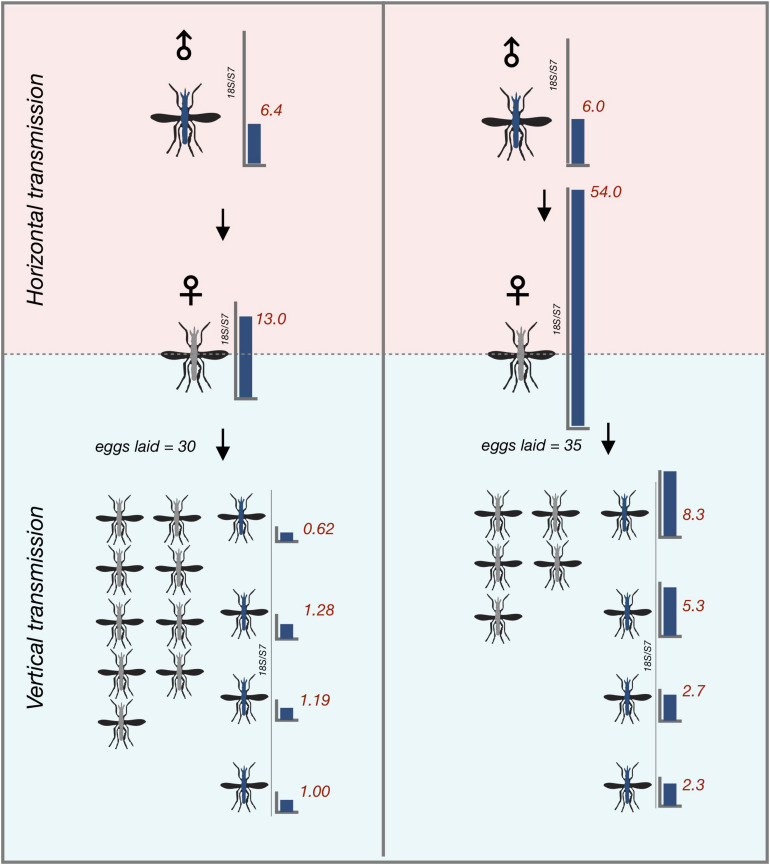

To determine whether An. arabiensis females that horizontally acquired Microsporidia MB from the infected males could vertically transfer the infection to their offspring, we gave the recipient An. arabiensis females from all single male transmission cages a blood meal and collected eggs from them. Notably, only 4 out of 22 (18%) females successfully acquired a blood meal. Two out of the 4 female An. arabiensis that successfully acquired a blood meal laid eggs. Eggs were then allowed to develop into adults prior to being screened. Microsporidia MB was detected in 37% of the progeny of recipient female An. arabiensis mosquitoes, indicating that Microsporidia MB that is horizontally acquired can be subsequently vertically transmitted in the next gonotrophic cycle (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Vertical transmission of horizontally acquired Microsporidia MB infections in An. arabiensis. Vertical transmission of Microsporidia MB is observed in recipient females that have become infected with Microsporidia MB after being kept with Microsporidia MB infected donor males in the first gonotrophic cycle after horizontal acquisition. Red numbers indicate Microsporidia MB infection intensity in individual An. arabiensis adults as determined by qPCR.

Microsporidia MB Was Not Detected in Potential Secondary Hosts

Since microsporidians can have complex life cycles that involve secondary hosts, we screened a number of other mosquito species and aquatic organisms that inhabit the same habitats as An. arabiensis in Western Kenya. Microsporidia MB was not detected in mosquitoes in the genus Aedes and Culex as well as Culicoides midges (Table 6). In addition, no Microsporidia MB infections were found in crustaceans in the genera Mesocyclops, Macrocyclops and Daphnia. Microsporidia MB was detected in Anopheles funestus s.s. but not Anopheles coustanii. While this survey of potential secondary hosts was not exhaustive, these findings suggest that Microsporidia MB is likely to be an Anopheles-specific symbiont.

TABLE 6.

Microsporidia MB was not observed in non-anopheline arthropods from the same habitats as An. arabiensis.

| Genus of organism | Total number of individuals screened | Collection sites (n) | Presence of Microsporidia MB |

| Aedes aegypti | 215 | Kilifi/Malindi | No infection |

| Aedes sp. | 10 | Mbita | No infection |

| Culex quinquefaciatus | 82 | Kilifi/Malindi (15), Nairobi (37), and Mbita (30) | No infection |

| Culex sp. | 61 | Kilifi/Malindi | No infection |

| Culicoides sp. | 42 | Ahero (20) and Mwea (22) | No infection |

| Anopheles coustanii | 42 | Ahero (20) and Mwea (22) | No infection |

| Anopheles funestus s.s. | 73 | Ahero (73) | Microsporidia MB in 5 specimens |

| Mesocyclops sp. | 34 | Ahero (5) and Mwea (29) | No infection |

| Macrocyclops sp. | 51 | Ahero (20) and Mwea (31) | No infection |

| Daphnia sp. | 20 | Ahero (15) and Mwea (5) | No infection |

Discussion

The results clearly demonstrate that Microsporidia MB is transmitted horizontally between adult An. arabiensis. Transmission was only observed in cages that had opposite sexes of Microsporidia MB infected and uninfected adult An. arabiensis suggesting that Microsporidia MB is transmitted sexually. Anopheles gambiae s.l. males package seminal fluid that is produced in the male accessory glands into a coagulated mating plug that is digested in the female atrium several days after mating (Giglioli and Mason, 1966). Sperm received by mated female Anopheles are stored in a dedicated organ called the spermatheca, which is relied upon by Anopheles gambiae s.l. females for a lifetime of offspring production (Tripet et al., 2003). We observed that Microsporidia MB intensity was much higher in the midgut and male gonads than in the carcass of male An. arabiensis. This suggests that Microsporidia MB either migrates to or proliferates in the male gonad. We observed multinucleate Microsporidia cells only in specimens that were infected with Microsporidia MB, indicating that these cells are developmental stages of Microsporidia MB. Microsporidia MB cells were specifically localized to the An. arabiensis male ejaculatory duct. The Microsporidia MB cells observed had either 4 or 8 nuclei, which likely indicates that Microsporidia MB sporogenesis is occurring in the An. arabiensis male ejaculatory duct as 4-nuclei sporogonial plasmodia develop into an 8-nuclei stage and finally to become sporophorous vesicles. This developmental sequence has been reported in greater detail in Microsporidians associated with fire ants (Sokolova and Fuxa, 2008) and Daphnia (Refardt et al., 2008). It is therefore likely that the sporogenesis of Microsporidia MB in the male ejaculatory duct produces infectious spores that are released with seminal secretions and therefore transferred to females upon mating. Transmission from female to male An. arabiensis was also observed, but further investigation will be required to establish the basis of this transmission route.

Two findings indicate that mating is required for Microsporidia MB transmission. Firstly, the absence of Microsporidia MB transmission in same sex transmission cage experiments, and secondly the finding that in the three cage experiments where female An. arabiensis spermatheca were checked for the presence of sperm, only inseminated females acquired Microsporidia MB. The experimental design precluded the quantification of precise transmission rates, since in the majority of experiments female insemination events were not confirmed. However, in light of the low rate of female insemination in cages where spermatheca were checked, it can be expected that the rate of Microsporidia MB transmission from males to female An. arabiensis per successful mating is likely to be high.

The number of females infected and the intensity of Microsporidia MB infections in recipient females was not dependent on the intensity of Microsporidia MB in donor males. A possible explanation for this finding is that Microsporidia MB are localized to midguts and gonads. It is possible that localization to the male gonad is a pre-requisite for sexual transmission and that only the intensity of Microsporidia MB infection in gonads is correlated with transmission capacity. The finding that Microsporidia MB intensity was high in the midgut and that some male An. arabiensis had high intensity of Microsporidia MB only in the midgut suggests that this organ may play a yet to be determined role in transmission or alternatively that the midgut is a reservoir of Microsporidia MB. Notably, since the majority of gonadal tissue development occurs during metamorphosis, localization to the midgut could be required for maintenance of Microsporidia MB infection in An. arabiensis larval stages.

From the perspective of symbionts that are strictly maternally inherited, males are a dead end. In many cases, including for maternally inherited microsporidians, this can lead to the evolution of feminization or male-killing (Ironside and Alexander, 2015). Another possible outcome is that maternally inherited infections evolve to become sexually transmitted. The sexual transmission of beneficial heritable microbes has been reported in aphids (Moran and Dunbar, 2006). It is probable that in aphids sexual transmission enabled decreased pathogenicity of symbionts and co-evolution toward obligate mutualism.

Sexual horizontal transmission has been reported in a variety of insect-associated microsporidians (Knell and Mary Webberley, 2004) and in most cases it is associated with other complementary forms of transmission. Sexual transmission is likely to be more effective in insect species that have overlapping generations and higher levels of promiscuity. In Anopheles, the bacterial symbionts Asaia (Favia et al., 2007) and Serratia AS1 (Wang et al., 2017) have been shown to be sexually transmitted. It is notable that Anopheles gambiae s.l. is largely monandrous and therefore it is unlikely that symbionts could rely solely on sexual horizontal transmission. Indeed, both Asaia and Serratia AS1 are also transmitted vertically and by other horizontal transmission routes. It is notable that sexually transmitted infections of insects tend to reach much higher prevalence levels than infections with other forms of horizontal transmission (Knell and Mary Webberley, 2004). An example is the Microsporidian Nosema calcarati, which is sexually and vertically transmitted in its host Pitogenes calcaratus and found at a prevalence of 50% (Purrini and Halperin, 1982). High prevalence may be in part due to the fact that sexual transmission selects for lower levels of virulence toward the hosts. Sexually transmitted infections can manipulate insect host physiology or behavior to favor higher levels of transmission, for example sexually transmitted mites were shown to increase the mating success of male midge hosts (McLachlan, 1999). Whether any sexually transmitted pathogens of Anopheles affect mating behavior has not been established.

Microsporidia MB was not found in non-anopheline arthropods that are found in the same habitats as An. arabiensis larvae. Since Microsporidia MB is transmitted vertically and by sexual horizontal transmission, a high level of host specificity could be expected since neither vertical (Herren et al., 2020), nor sexual horizontal transmission would be effective across species. It is noteworthy that Microsporidia MB was found in another species of anopheline mosquito, An. funestus s.s., which is a primary vector of malaria in Sub-Saharan Africa. If the Microsporidia MB found in An. funestus s.s have similar characteristics to Microsporidia MB found in An. arabiensis, including Plasmodium transmission blocking, then Microsporidia MB could be developed as a tool for malaria control in several primary vector species.

To be successfully developed into a strategy to control malaria, an effective method of disseminating Microsporidia MB into Anopheles populations will need to be established. Our results show that Microsporidia MB infected male mosquitoes can infect their female counterparts and that horizontally infected females can transmit Microsporidia MB to their offspring. We previously showed that Microsporidia MB is vertically transmitted in An. arabiensis (Herren et al., 2020) and therefore Microsporidia MB infected males for releases could be produced by sorting the offspring of Microsporidia MB infected An. arabiensis colonies. These findings could be the basis for a dissemination strategy that involves targeted release of Microsporidia MB infected male Anopheles mosquitoes, potentially avoiding the need to release biting females, which would be advantageous in terms of community engagement and acceptance of the intervention. In principle, such a strategy would be similar to the mass-release of sterile males (Bouyer et al., 2020), except that instead of sterilizing females Microsporidia MB infected males would decrease the capacity of infected females and their offspring to transmit malaria for multiple generations. The capacity of Microsporidia MB to be vertically transmitted after infecting females would potentially make this approach more sustainable and cost-effective than SIT.

Materials and Methods

Field Collections

Resting gravid and engorged female mosquitoes were collected indoors through manual aspiration. Collections were undertaken in Ahero (–34.9190W, –0.1661N) and Mwea (–37.3538W, –0.6577N) between Feb and June 2020 between 0630 h and 0930 h using electric torches/lights and aspirators. Collected females were placed in large cages supplied with 6% glucose and transported to icipe-Thomas Odhiambo Campus (iTOC) from Ahero and icipe Duduville campus from Mwea for processing. Mosquito larvae and other organisms were collected from larval habitats in Mwea and Ahero using larval collection dippers between March and July 2019. Anopheles funestus and coustanii were collected in November 2018 in Ahero as adults in houses (for Anopheles funestus) and cattle-baited traps (for Anopheles coustanii). Aedes aegypti and Culex sp. larval stages were collected in March 2018 from old discarded wheel tires in Kilifi and Malindi and transported to the rearing facility at Pwani University for emergence.

Mosquito Identification, Processing, and Rearing

All transmission experiments were carried out on wild-collected Anopheles gambiae sl., which were identified morphologically. In all of the collection sites, An. arabiensis is the most common member of the An. gambiae species complex, with >97% of complex members being identified as An. arabiensis. The high percentage of An. arabiensis in field collections from both sites was re-confirmed using PCR (Santolamazza et al., 2008). An. funestus species were identified by PCR (Koekemoer et al., 2002). Wild collected mosquitoes were maintained in an insectary at 27 ± 2.5oC, humidity 60–80% and 12-h day and 12-h night cycles and induced to oviposit in individual microcentrifuge tubes containing a wet 1 cm × 1 cm Whatman filter paper. Eggs from each female were counted under a compound microscope using a paint brush and then dispensed into water tubs for larval development at 30.5°C and 30–40% humidity. TetraminTM baby fish food was used to feed developing larvae. Upon laying eggs, the G0 females were screened for presence of Microsporidia MB by PCR. The larval offspring of Microsporidia MB positive field-caught female mosquitoes were pooled into larval rearing troughs for experimentation. Microsporidia MB uninfected controls were obtained from the An. arabiensis colonies at icipe iTOC Mbita and Duduville campuses.

Inoculation of Microsporidia MB Homogenate by Feeding

Five infected An. arabiensis larvae or adults were placed in 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes containing 500 μl 1 × PBS. An. arabiensis larvae and adults were homogenized using a pestle and then transferred directly into larval rearing water or sugar sources. For larval rearing water, 500 μl homogenate was added to 500 ml of distilled water at the L2 larval stage. For adults, 250 μl homogenate was added to 20 ml of 10% sucrose solution. Recipient larvae that developed in rearing water with homogenate were screened as 1–2 day old adults. Recipient adults were screened 2 days after initial homogenate exposure. Aliquots of the homogenate were kept at −20°C and screened by PCR, all homogenates used were Microsporidia MB positive.

Transmission Between Live An. arabiensis Larvae

Microsporidia MB infected donor and uninfected recipient An. arabiensis larvae (donor N = 7–20 and recipient N = 9–31) were transferred into a 15 cm x 30 cm larval rearing trough that had a 70 μm mesh divider between two sections. Donor and recipient larvae were placed in separated sections and maintained until they emerged as adults. Both donor and recipient An. arabiensis were screened as 1–2 day old adults to determine the percentage of donors that were infected and if recipients had horizontally acquired Microsporidia MB.

Transmission Between Live An. arabiensis Adults

Microsporidia MB infected and uninfected An. arabiensis virgin adults were transferred into 30 cm × 30 cm × 30 cm cages. Virgin mosquitoes were obtained by separating the sexes at the pupal stage after visual examination of the terminalia. To increase the chances of observing transmission, several (2–6) Microsporidia MB infected An. arabiensis donors were kept with 12–25 virgin uninfected recipient mosquitoes for 2 days. In the experiments where sex could not be used to differentiate male and female mosquitoes, dyes (red and blue) were used to mark mosquito wings and indicate donors and recipients. Upon completion of the transmission experiment all An. arabiensis mosquitoes were screened to determine the percentage of donors that were infected and if recipients had horizontally acquired Microsporidia MB. To investigate the efficiency of horizontal transmission and the importance of Microsporidia MB intensity, additional cages with single Microsporidia MB infected donor males and 10–50 virgin Microsporidia MB uninfected recipient females were established and maintained for 2 days. In the single infected donor male cage experiments, post exposure, female recipients were allowed to feed on a human arm for 15 min at 19:00 h. Mosquitoes that fed were placed in individual micro centrifuge tubes with wet filter papers to induce oviposition Upon completion of the transmission experiment all An. arabiensis mosquitoes were screened by qPCR to determine the infection status and intensity of donor and recipient An. arabiensis. The offspring from Microsporidia MB infected recipient females from single male cage experiments were reared until they were 1–2 day old adults and then screened for Microsporidia MB to determine if vertical transmission had occurred. To investigate mating rates and the link between acquiring Microsporidia MB and female insemination status, the presence of sperm in An. arabiensis females maintained in some of the cages with Microsporidia MB infected males were examined by the dissection of spermathecae and scoring sperm presence.

Quantification of Microsporidia MB Distribution Across Male An. arabiensis Organs

Quantification of Microsporidia MB was conducted on dissected organs from G1 Microsporidia MB-infected An. arabiensis adult males, 3–5 days post emergence. Midguts and gonads were separated from the remainder of the mosquito which was designated as the carcass. Each organ and the carcass was individually screened for Microsporidia MB presence and intensity by qPCR. Quantification of Microsporidia MB in the male seminal fluid was carried out on different An. arabiensis specimens. Briefly, 10–12 day old males were decapitated and used immediately in forced mating experiments with virgin females (full method given at www.mr4.org). Upon successful copulation, seminal secretions produced by the male were collected with a pulled capillary tube and transferred to a 10uL 1 × PBS and placed under ice. Genomic DNA was collected as previously described prior to Microsporidia MB quantification by qPCR.

Microscopy of An. arabiensis Male Gonad

Microscopy was conducted on dissected G1 Microsporidia MB-infected and uninfected (control) An. arabiensis adult male gonads, 3–5 days post emergence. Gonads were fixed in 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution for 30 min. After three quick washes with PBS-T, samples were stained in 0.1mM Syto-9 in PBS for 1 h. After two quick washes and one 10 min wash, the gonads were placed on a slide and were visualized immediately using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, United States). Images were analyzed with the ImageJ 1.50i software package (Schneider et al., 2012).

Specimen Storage and DNA Extraction

All An. arabiensis specimens were dry frozen at –20°C in individual microcentrifuge tubes prior to DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from each section individually using the protein precipitation method (Puregene, Qiagen, Netherlands).

Molecular Detection of Presence and Intensity of Microsporidia MB

Microsporidia MB specific primers (MB18SF: CGCCGG CCGTGAAAAATTTA and MB18SR: CCTTGGACGTG GGAGCTATC) were used to detect Microsporidia MB in An. arabiensis larvae and adults (Herren et al., 2020). A 10 μl PCR reaction consisted of 2 μl HOTFirepol® Blend Master mix Ready-To-Load (Solis Biodyne, Estonia, mix composition: 7.5 mM Magnesium chloride, 2 mM of each dNTPs, HOT FIREPol® DNA polymerase), 0.5 μl of 5 pmol μl–1 of forward and reverse primers, 2 μl of the template and 5 μl nuclease-free PCR water was undertaken. Conditions used were initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 62°C for 90 s and extension at 72°C for a further 60 s. Final elongation was done at 72°C for 5 min. The intensity of Microsporidia MB infection was determined by a qPCR assay using MB18SF/MB18SR primers. These were normalized against the Anopheles ribosomal S7 host gene primers (S7F: 5′TCCTGGAGCTGGAGATGAAC3′ and S7R 5′GACGGGTCTGTACCTTCTGG3′, Dimopoulos et al., 1998).

Statistical Analysis

We carried out statistical analyses using the two-tailed paired spearman’s rank test to compare paired donor and recipient Microsporidia MB intensity data values which had a non-normal distribution. To analyze if donor Microsporidia MB intensity or number of available mates affected the odds of Microsporidia MB transmission, a logistic regression analysis was carried out. All statistical analyses were undertaken using GraphPad Prism version 6.0c software and R (version 3.5.3). P-values of ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 were deemed to be statistically significant.

Data Availability Statement

All the datasets presented in this study can be found an online repository: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14846925.v2.

Author Contributions

JH and GN conceived and designed the majority of the experiments. GN, TM, TB, and EEM performed the majority of the experiments. GN, EEM, TM, DM, and EO collected mosquitoes and screened them for symbionts. JH, SS, EM, EEM, LM, ET, JP, JB, GN, TB, TO, FO, and GM analyzed the data. JH, TO, and FO carried out the microscopy. JH and GN wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Milcah Gitau of icipe Arthropod Rearing and Containment Unit as well as David Alila and Elisha Obudo from iTOC for mosquito rearing assistance. We thank Ibrahim Kiche, Faith Kyengo, Ulrike Fillinger, and Dan Masiga for advice and assistance.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by Open Philanthropy (SYMBIOVECTOR Track A) and the BBSRC (BB/R005338/1, sub-grant AV/PP015/1). The International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe) receives support from the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, and the Government of Kenya. GN was supported by the African Union under the Pan African University Institute for Basic Sciences Technology & Innovation (PAUSTI) postgraduate scholarship.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.647183/full#supplementary-material

The intensity of Microsporidia MB in recipient females is not correlated to donor male intensity, with a regression slope that does not significantly differ from zero (P = 0.34, r = 0.177, and n = 31).

References

- Ant T. H., Herd C. S., Geoghegan V., Hoffmann A. A., Sinkins S. P. (2018). The Wolbachia strain wAu provides highly efficient virus transmission blocking in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathog. 14:e1006815. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baton L. A., Ranford-Cartwright L. C. (2005). Spreading the seeds of million-murdering death: metamorphoses of malaria in the mosquito. Trends Parasitol. 21 573–580. 10.1016/J.PT.2005.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S., Weiss D. J., Cameron E., Bisanzio D., Mappin B., Dalrymple U., et al. (2015). The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature 526 207–211. 10.1038/nature15535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian G., Xu Y., Lu P., Xie Y., Xi Z. (2010). The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia induces resistance to dengue virus in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000833. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer J., Yamada H., Pereira R., Bourtzis K., Vreysen M. J. B. (2020). Phased conditional approach for mosquito management using sterile insect technique. Trends Parasitol. 36 325–336. 10.1016/j.pt.2020.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro U. (2018). “Malaria elimination: challenges and opportunities,” in Towards Malaria Elimination - A Leap Forward eds Manguin S., Dev V. (London: IntechOpen; ), 3–12. 10.5772/intechopen.77092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulos G., Seeley D., Wolf A., Kafatos F. C. (1998). Malaria infection of the mosquito Anopheles gambiae activates immune-responsive genes during critical transition stages of the parasite life cycle. EMBO J. 17 6115–6123. 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favia G., Ricci I., Damiani C., Raddadi N., Crotti E., Marzorati M., et al. (2007). Bacteria of the genus Asaia stably associate with Anopheles stephensi, an Asian malarial mosquito vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 9047–9051. 10.1073/pnas.0610451104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frentiu F. D., Frentiu F. D., Zakir T., Zakir T., Walker T., Walker T., et al. (2014). Limited dengue virus replication in field-collected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8:e2688. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglioli M. E. C., Mason G. F. (1966). The mating plug in anopheline mosquitoes. Proc. R. Entomol. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Gen. Entomol. 41 123–129. 10.1111/j.1365-3032.1966.tb00355.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han B., Weiss L. M. (2017). “Microsporidia: obligate intracellular pathogens within the fungal kingdom,” in The Fungal Kingdom, eds Heitman J., Howlett B. J., Crous P. W., Stukenbrock E. H., James T. Y., Gow N. A. R. (Washington DC: American Society for Microbiology; ), 97–113. 10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0018-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herren J. K., Mbaisi L., Mararo E., Makhulu E. E., Mobegi V. A., Butungi H., et al. (2020). A microsporidian impairs Plasmodium falciparum transmission in Anopheles arabiensis mosquitoes. Nat. Commun. 11:2187. 10.1038/s41467-020-16121-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann A. A., Montgomery B., Popovici J., Iturbe-Ormaetxe I., Johnson P., Muzzi F., et al. (2011). Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature 476 454–457. 10.1038/nature10356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijben S., Paaijmans K. (2018). Putting evolution in elimination: winning our ongoing battle with evolving malaria mosquitoes and parasites. Evol. Appl. 11 415–430. 10.1111/eva.12530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironside J. E., Alexander J. (2015). Microsporidian parasites feminise hosts without paramyxean co-infection: support for convergent evolution of parasitic feminisation. Int. J. Parasitol. 45 427–433. 10.1016/J.IJPARA.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellen W. R., Lindegren J. E. (1971). Modes of transmission of Nosema plodiae Kellen and Lindegren, a pathogen of Plodia interpunctella (Hübner). J. Stored Prod. Res. 7 31–34. 10.1016/0022-474X(71)90035-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knell R. J., Mary Webberley K. (2004). Sexually transmitted diseases of insects: distribution, evolution, ecology and host behaviour. Biol. Rev. 79 557–581. 10.1017/S1464793103006365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koekemoer L. L., Kamau L., Hunt R. H., Coetzee M. (2002). A cocktail polymerase chain reaction assay to identify members of the Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66 804–811. 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan A. (1999). Parasites promote mating success: the case of a midge and a mite. Anim. Behav. 57 1199–1205. 10.1006/anbe.1999.1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran N. A., Dunbar H. E. (2006). Sexual acquisition of beneficial symbionts in aphids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 12803–12806. 10.1073/pnas.0605772103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira L. A., Iturbe-Ormaetxe I., Jeffery J. A., Lu G., Pyke A. T., Hedges L. M., et al. (2009). A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell 139 1268–1278. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazni W. A., Hoffmann A. A., NoorAfizah A., Cheong Y. L., Mancini M. V., Golding N., et al. (2019). Establishment of Wolbachia strain wAlbB in Malaysian populations of Aedes aegypti for dengue control. Curr. Biol. 29 4241–4248.e5. 10.1016/J.CUB.2019.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purrini K., Halperin J. (1982). Nosema calcarati n. sp. (Microsporidia), a new parasite of Pityogenes calcaratus Eichhoff (Col., Scolytidae). Z. Angew. Entomol. 94 87–92. 10.1111/j.1439-0418.1982.tb02549.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Refardt D., Decaestecker E., Johnson P. T. J., Vávra J. (2008). Morphology, molecular phylogeny, and ecology of Binucleata daphniae n. g., n. sp. (Fungi: Microsporidia), a parasite of Daphnia magna Straus, 1820 (Crustacea: Branchiopoda). J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 55 393–408. 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romoli O., Gendrin M. (2018). The tripartite interactions between the mosquito, its microbiota and Plasmodium. Parasit. Vectors 11:200. 10.1186/s13071-018-2784-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santolamazza F., Mancini E., Simard F., Qi Y., Tu Z., Della Torre A. (2008). Insertion polymorphisms of SINE200 retrotransposons within speciation islands of Anopheles gambiae molecular forms. Malar. J. 7:163. 10.1186/1475-2875-7-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S., Eliceiri K. W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9 671–675. 10.1038/nmeth.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova Y. Y., Fuxa J. R. (2008). Biology and life-cycle of the microsporidium Kneallhazia solenopsae Knell Allan Hazard 1977 gen. n., comb. n., from the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Parasitology 135 903–929. 10.1017/S003118200800440X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stentiford G. D., Stentiford G. D., Feist S. W., Feist S. W., Stone D. M., Stone D. M., et al. (2013). Microsporidia: diverse, dynamic, and emergent pathogens in aquatic systems. Trends Parasitol. 29 567–578. 10.1016/j.pt.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripet F., Touré Y. T., Dolo G., Lanzaro G. C. (2003). Frequency of multiple inseminations in field-collected Anopheles gambiae females revealed by DNA analysis of transferred sperm. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 68 1–5. 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.68.1.0680001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vávra J., Lukeš J. (2013). “Chapter: Microsporidia and ‘the art of living together’,” in Advances in Parasitology, Vol. 82 ed. Rollinson D. (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; ), 253–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossbrinck C. R., Debrunner-Vossbrinck B. A. (2005). Molecular phylogeny of the Microsporidia: ecological, ultrastructural and taxonomic considerations. Folia Parasitol. 52 131–142. 10.14411/fp.2005.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker T., Johnson P. H., Moreira L. A., Iturbe-Ormaetxe I., Frentiu F. D., McMeniman C. J., et al. (2011). The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature 476 450–453. 10.1038/nature10355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Dos-Santos A. L. A., Huang W., Liu K. C., Oshaghi M. A., Wei G., et al. (2017). Driving mosquito refractoriness to Plasmodium falciparum with engineered symbiotic bacteria. Science 357 1399–1402. 10.1126/science.aan5478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020). WHO | The World Malaria Report 2020. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The intensity of Microsporidia MB in recipient females is not correlated to donor male intensity, with a regression slope that does not significantly differ from zero (P = 0.34, r = 0.177, and n = 31).

Data Availability Statement

All the datasets presented in this study can be found an online repository: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14846925.v2.