Abstract

Background

Secondary schools have attempted to address gaps in help-seeking for mental health problems with little success. This trial evaluated the effectiveness of a universal web-based service (Smooth Sailing) for improving help-seeking intentions for mental health problems and other related outcomes among students.

Methods

A cluster randomised controlled trial was conducted to evaluate the 12-week outcomes of the Smooth Sailing service among 1841 students from 22 secondary schools in New South Wales, Australia. Assignment was conducted at the school level. The control condition received school-as-usual. The primary outcome was help-seeking intentions for general mental health problems at 12-weeks post-baseline. Secondary outcomes included help-seeking behaviour, anxiety and depressive symptoms, psychological distress, psychological barriers to help-seeking, and mental health literacy. Data were analysed using mixed linear models. This trial was registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12618001539224).

Findings

At 12-weeks post-baseline, there was a marginal statistical difference in the relative means of help-seeking intentions (effect size=0•10, 95%CI: -0•02–0•21) that favoured the intervention condition. Help-seeking from adults declined in both conditions. There was a greater reduction in the number of students who “needed support for their mental health but were not seeking help” in the intervention condition (OR: 2•08, 95%CI: 1•72–2.27, P<•0001). No other universal effects were found. Participants found the service easy to use and understand; However, low motivation, time, forgetfulness, and lack of perceived need were barriers to use.

Interpretation

Smooth Sailing led to small improvements in help-seeking intentions. Refinements are needed to improve its effectiveness on other mental health outcomes and to increase student uptake and engagement.

Funding

HSBC and Graf Foundation.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depression, Web-based, School, Stepped care

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study

We conducted a comprehensive search on PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar to identify any studies published prior to December 2020 of school-based screening and follow-up services that aimed to improve mental health outcomes (help-seeking, anxiety, depression) among adolescents. The following terms were used: mental health OR anxiety OR depression OR suicid* AND help seek* OR seek help OR help seeking behav* OR self refer OR self help OR health care seeking behav AND adolescen* OR youth AND schools OR "school based" AND screen* OR universal OR screening tests OR identif* OR case identif* OR detect* OR assess* OR evaluat* OR rate OR measure OR psychological assess* OR questionnaires OR inventories OR test* OR battery OR scale* OR symptom checklist AND program OR management options OR intervention OR referral OR follow up OR care OR treat. Most studies were pre-post intervention trials of single-use screening tools. Few studies conducted universal screening using digital platforms or delivered automated, web-based care to those who screened positive. Further, few studies examined the potential of a stepped-care model or evaluated service effectiveness using a controlled trial.

Added value of this study

This study extends prior research by conducting a cluster randomised controlled trial to demonstrate that the Smooth Sailing service model may improve intentions to seek help for general mental health problems among secondary school students. The service may also help schools to identify students in need and provide initial care. However, refinements are needed to improve service uptake and engagement among students.

Implications of all the available evidence

While there has been great interest in utilising school settings to improve help-seeking for mental health problems through the delivery of programs and services, this study demonstrates that this can be challenging, hampered by a reluctance of schools and students to be involved in mental health services research and a lack of statistically significant effects on important mental health outcomes.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Despite a genuine need for care, fewer than 50% of adolescents with mental health problems seek professional help.1 This is of significant concern because mental illnesses are treatable and positive attitudes to help-seeking are critical to recovery.2 Secondary schools are increasingly implementing a range of programs to address the gap in help-seeking for mental health; However, there is little evidence available to guide schools on which type of service model will provide timely and appropriate care to all students who require it.3,4 Many schools adopt a traditional “wait-to-act” approach in which various mental health personnel and supports are provided, but the onus is on students or parents to seek help, or on teachers to identify students in need. This model of care is negated by a range of barriers including poor mental health knowledge, stigma, students’ desire for autonomy, and a lack of mental health expertise among youth, their families[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], and school staff.10 Further, the extent and quality of mental health resources varies across schools.11 New service models are needed to improve help-seeking by proactively reaching out to youth to offer high quality care.

School-based mental health screening programs have been found to identify a significantly greater proportion of students in need of support when compared to traditional wait-to-act models.12,13 These initiatives have increased help-seeking behaviour among youth by expediting access to care.14 The data generated from screening programs has also been used to inform decision-making on the need for other school-based interventions, policies and resources, enabling schools to adopt more evidence-based approaches.[15], [16], [17] Triaging processes, brief intervention approaches, and multi-tiered systems of support have also been trialled in various school settings with promising results.18,19 However, uptake of universal mental health screening in schools has been low. A recent study of US school administrators found that although 75% were extremely interested, less than 2% had implemented any such intervention.20 Lack of access, funding, and limited systems to support student follow-ups were barriers to use21 together with a range of implementation and feasibility factors (e.g. administrative support, scheduling, consent, and liability).22,23 A lack of empirical evidence also impedes uptake. Although many advocates argue for the use of screening and referral as a strategy for early identification and treatment in youth3,24, a recent systematic review of school-based programs identified only one randomised controlled trial.25 There is a demonstrated need for service models that not only identify students in need, but also provide ongoing care using methods that are easily disseminated, scalable, and rigorously evaluated.26

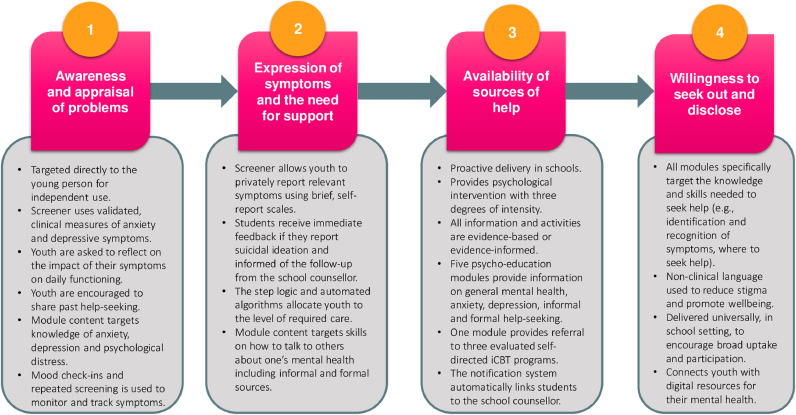

The Black Dog Institute has developed a universal, web-based mental health service (Smooth Sailing) that aims to improve secondary school students’ help-seeking intentions for mental health problems.[27], [28], [29] The service model is informed by Rickwood and colleagues30 theory of help-seeking for mental health, which characterises help-seeking as a translational process that involves awareness and appraisal of problems, expression of symptoms and need for support, availability of sources of help, and the willingness to disclose problems and seek out care. As shown in Figure 1, the Smooth Sailing service model integrates various components to directly target some of the factors that have been found to facilitate or inhibit help-seeking in youth.

Figure 1.

Smooth Sailing: Application of Rickwood and colleagues’30 theory of help-seeking for mental health problems in youth.

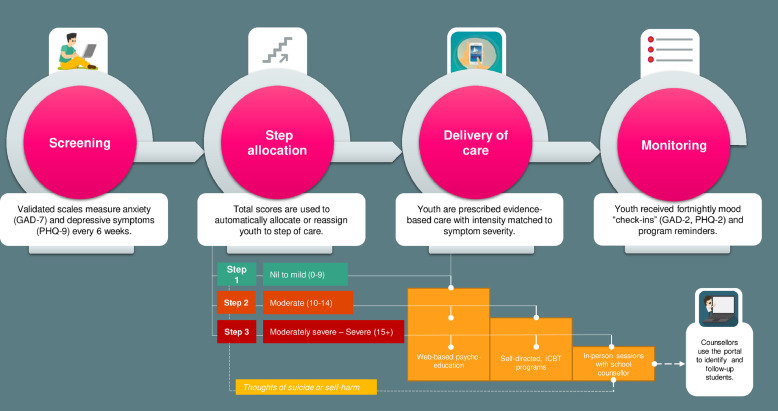

Delivered in the classroom, the Smooth Sailing service model directly opposes a wait-to-act approach to help-seeking by combining automated symptom screening for anxiety, depression, and suicidality with mandated care and follow-up. Based on the principles of stepped care31, the intensity of the help provided is matched to the severity of symptoms (see Figure 2) and is consistent with Australian clinical practice guidelines32 and other stepped care models for depression and anxiety.33,34 Screening for symptoms is repeated every six weeks and care is adapted accordingly (see supplementary material). A pilot study provided initial evidence of the need, acceptability, and feasibility of the service.35 One in five students screened by the service required follow-up from school counsellors. The non-confrontational nature of the digital delivery appeared to be aligned with young people's preferences for receiving mental health information and support online.36 The low intensity and non-clinical approach aimed to ease non-help-seeking youth into care, allowing them to progress to more intensive forms of support over time. Enhancements to the service were made based on students’ feedback.

Figure 2.

The Smooth Sailing service model: Step criteria and care provided.

Current study

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the Smooth Sailing service model for improving help-seeking intentions for general mental health problems among secondary school students in New South Wales, Australia, relative to a school-as-usual control condition. It was hypothesised that students using the Smooth Sailing service would report higher levels of help-seeking intentions for general mental health problems at 12-weeks post-baseline compared to students in the control condition. This study also examined the secondary impacts of the service model on help-seeking behaviour for mental health problems, symptoms of anxiety and depression, psychological distress, psychological barriers to help-seeking, and mental health literacy. It was hypothesised that students using the Smooth Sailing service would report greater improvements in help-seeking behaviour from adult sources, reduced levels of anxiety, depression, psychological distress, psychological barriers to help-seeking, and improved mental health literacy at 12-weeks post-baseline. It was also hypothesised that the Smooth Sailing service would be more effective for reducing the number of students who were not actively seeking help for their mental health problems, despite a need for support. The current study also measured service use, satisfaction, and barriers to use among participants using the service. This study provides important information about the usefulness of a web-based service model that blends automated screening, digital interventions, and in-person professional support for improving help-seeking when delivered universally in secondary schools.

Methods

Trial design

The full trial protocol has been published elsewhere.37 A two-arm cluster RCT was conducted with schools as clusters and individual students as participants. All outcome measures pertained to the individual participant level. Help-seeking intentions (primary outcome) and behaviours (secondary outcome) were assessed at baseline and 12-weeks post-baseline with symptom measures (secondary outcomes) assessed at baseline, 6- and 12-weeks post-baseline. Ethics approvals were obtained from the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HC17910), the State Education Research Applications Process for the New South Wales Department of Education (2016471), the Sydney Catholic Schools Research Centre (20186), and the Catholic Schools Office Diocese of Maitland-Newcastle. The trial was registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12618001539224).

Participants

This study took place between February 2018 to December 2018 in secondary schools located in the state of New South Wales, Australia. All baseline data was collected in the first term of the school year (22nd February to 4th April 2018, Weeks 4 to 10). To be eligible to participate, schools were required to have a school counsellor onsite for the duration of the study. Secondary school adolescents (age range: 11 to 19 years) from the nominated student grades (7 to 12) who attended the participating schools were eligible to take part. Students were required to have an active email address for the duration of the study.

Group assignment and masking

Schools were assigned to a single condition (cluster design) to avoid contamination and for administrative feasibility. Assignment was carried out according to the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines by an external researcher not involved in the study activities. Assignment occurred after the school principals provided their letter of consent. A minimisation approach to assignment was used to ensure balance across the conditions in terms of the Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA) level (< 1000 versus ≥ 1000), gender mix (co-educational versus single sex) and student grade involved (Grade 9 students only versus multiple or other grades). Minimisation was undertaken in Stata version 14.2 using the rct_minim procedure. Schools and researchers were not blinded to the assignment, but students were not informed of their school's allocation.

Sample size

The target sample size for this study was 1600 students from approximately 16 schools, based on the typical student enrolment profiles of secondary schools in New South Wales.38 The sample size calculation was determined using an effect size of 0•20 on the primary outcome5,39,40 and attrition rate of 20% among student participants.41 The statistical power was set at 0•80, alpha at •05 (2-tailed), and a correlation of 0•50 was assumed between the scores at baseline and endpoint.42 A design effect was calculated assuming an intraclass correlation of 0•02 to allow for possible clustering effects.

Recruitment and consent

Schools were recruited using various arms-length methods. Study adverts featured in the Black Dog Institute New South Wales School Counsellors e-Newsletter; the New South Wales School-Link newsletter (a state government initiative that links schools with local health services); the Black Dog Institute website and social media channels (Twitter, Instagram and Facebook); Academic conference presentations; Professional development courses; and Correspondence from the New South Wales Department of Education. Any interested school staff were invited to express interest by email to the Chief Investigator (CI). The CI followed up with a study information pack and a telephone call. To finalise participation, schools were required to provide a signed letter of principal support which confirmed the availability of an onsite school counsellor and nominated the student grade to receive the service. Once school letters of consent were received, schools were randomised and informed of their allocation. The research team then scheduled the school visits and mailed the appropriate student Participant Information and Consent Forms (PICFs). School staff distributed the PICFs to the relevant grade two weeks prior to the scheduled baseline visit. The PICF for the Intervention condition was required to include an additional clause to inform the students and their parents that they would be asked questions about suicidality and followed-up accordingly.

Students gave their informed consent to participate on the day of the baseline assessment via a signed PICF that was witnessed by the research team. An opt-out consent process was used for parents whereby schools informed parents of the study two weeks prior to the baseline school visit. Parents who did not wish for their child to partake were instructed to notify the school or research team. All participating schools located in the Sydney Catholic Diocese were required to have signed written consent from students and their parents. As part of the informed consent process, all students were required to complete a 6-item online Gillick competence test43 prior to starting the baseline surveys. This ensured students understood the terms and conditions of the research study.

Intervention

Schools assigned to the intervention condition were given access to the Smooth Sailing service for 12 weeks. The mental health screening conducted by Smooth Sailing consisted of the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7)44 and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),45 which determined students’ symptom levels. The study outcomes were embedded into the screening process. Using the total scores of the GAD-7 and PHQ-9, the service automatically allocated students to a step of care (see Figure 2) and provided students with a personalised dashboard which included generalised symptom feedback (e.g., “It looks like things have been really rough for you lately, we're sorry to hear that. We're here to help”) and an overview of the recommended modules.

The psychoeducation consisted of five 10-minute self-directed modules on general mental health, anxiety, depression, and help-seeking which were complimented by animations, illustrations, and hyperlinks to credible youth mental health services and websites. An additional module provided referral to two external, publicly accessible, free, evidence-based Internet Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (iCBT) programs for youth provided by Australian universities: MoodGym46 and The BRAVE Program47. These iCBT programs were provided external to the Smooth Sailing service and thus, the research team did not have access to the data collected by these programs. All module content was created specifically for the Smooth Sailing service and was reviewed by youth and health professionals in the co-design process. The content was also edited by a copywriter to ensure appropriate readability for young adolescents.

The Smooth Sailing service also included a notification system to link students to their school counsellors. Students allocated to step 3 and/or experiencing thoughts that that they would be better off dead or of hurting themselves (i.e., score > 0 on item 9 of the PHQ-9) triggered an immediate follow-up notification. School counsellors accessed and tracked these notifications using the purpose-built secure web-portal. School counsellors were provided with information guides to support the interpretation of students’ mental health scores and were instructed to use their school protocols when attending to students, initiating external referrals or parental contact when necessary. School counsellors were provided with a list of local mental health services to assist this process. To ensure student confidentiality, the researchers were not provided with specific detail on the actions taken or care provided by the school counsellors.

As part of the Smooth Sailing service, all students were invited to complete fortnightly mood check-ins sent via short message services (SMS) or email. This check-in consisted of the GAD-2 and PHQ-2 symptom scales. A total of four check-ins were sent during the study period. Students received generalised feedback and were prompted to use the program. All students were also sent fortnightly reminders to complete the modules. The mental health screening was repeated at 6- and 12-weeks post-baseline, and any student who had not responded to their allocated care (i.e., symptoms remained elevated or had worsened) were stepped up to the next level of care (see supplementary material). Due to the novelty of the service model and the short study period, no students were stepped down.

Control

The control was a 12-week school-as-usual condition, with some matched attention. Students in the control condition completed the outcome measures at baseline, 6- and 12-weeks post-baseline using an identical web-based platform to the intervention but were not given access to any of the additional service components (i.e., step allocations, symptom feedback, service modules, or school counsellor follow-up). As such, the governing ethics bodies did not permit the use of the PHQ-9 scale in the control condition because it examined suicidality and was a validated clinical measure used for Major Depressive Disorder. All students in the control condition were provided with a generalised help-seeking resource sheet after each of the study assessments. No limitations were placed on schools’ or students’ mental healthcare activities, practices, or help-seeking. Schools in the control condition were able to receive the Smooth Sailing service after the study was complete.

Procedure

The study procedure was consistent across both conditions. Researchers from the Black Dog Institute visited the schools to conduct the three study assessment sessions during class time. In the first school visit (baseline), after providing written consent, students were asked to access the study URL and register to the service. This involved providing their name, gender, date of birth, email, and mobile phone number. Students also provided their unique study code and created a password for their account. Students were then directed to complete the mental health screening, which consisted of the study outcomes. This process was repeated at 6- and 12-weeks post-baseline (primary endpoint). For schools in the intervention condition, researchers met with the school counsellor after the study assessment sessions to ensure the counsellors could use the portal to review and initiate the student follow-ups. The researchers did not provide any clinical supervision or support to the school counsellors and used a uniform instruction sheet to guide these meetings. The researchers contacted the school counsellors two days after each study visit to confirm the completion of the student follow-ups and to monitor any adverse events.

Outcome Measures

Primary outcome

General Help-Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ)48: The primary outcome for this study was participants’ intentions to seek help for general mental health problems, measured at baseline and 12-weeks post-baseline using the GHSQ. Participants were asked to rate how likely they were to seek help from 13 sources when having a tough time with their mental health. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘extremely unlikely’ to ‘extremely likely’. A total score was calculated (range: 13 to 65) with higher scores indicative of greater intentions to seek help. The GHSQ has demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties for measuring help-seeking intentions in youth and has been widely used in adolescents aged 11 to 18 years.49 In the current study, the total scores ranged from 13 to 65 and the Cronbach's alpha was •87.

Secondary outcomes

Actual Help-Seeking Questionnaire (AHSQ)30: To examine secondary improvements in actual help-seeking behaviour, the current study utilised the AHSQ delivered at baseline and 12-weeks post-baseline. Participants were asked (answered yes or no) whether they had turned to the same list of sources outlined in the GHSQ for help with any mental health issue in the past three months. To test the hypotheses, two categorical variables were used: the number of students seeking help from adult sources in the past three months (i.e. those who answered yes to seeking help from parents, teachers, other adults, school counsellor, general practitioners or mental health professionals) and the number of students who self-identified as needing support for their mental health but did not seek help from anyone (i.e. those who answered yes to the final item of AHSQ “I needed support but I did not seek help from anyone”). The AHSQ has been used extensively in equivalent samples1 and school-based research.42

Generalised Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7)44: This 7-item self-report scale measured the frequency of generalised anxiety symptoms at baseline, 6- and 12-weeks post-baseline using a 4-point likert scale. Total symptom scores were summed and then classified as ‘nil to mild’ (0 - 9), ‘moderate’ (10 - 14), or ‘moderately severe to severe’ (≥15). This scale has been used in young adolescents, with demonstrated specificity and sensitivity.50 In the current study, participants’ scores ranged from 0 to 21 and the Cronbach's alpha was •89.

Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale – Child version (CES-DC)51: This 20-item self-report scale measured depressive symptoms at baseline, 6- and 12-weeks post-baseline. Scores were summed (range: 0 to 60) with higher scores indicative of increased depression. This scale has been found to have good psychometric properties among children and adolescents.52 In the current study, participants’ scores ranged from 0 to 60 and the Cronbach's alpha was •93.

Distress Questionnaire-5 (DQ5)53: This 5-item population screener measured psychological distress at baseline, 6- and 12-weeks post-baseline. Scores were summed (range: 5 to 25) with higher scores indicative of greater psychological distress. This scale has demonstrated high internal consistency and convergent validity.53,54 It has also been used in other school-based mental health research.55 In the current study, participants’ scores ranged from 5 to 25 and the Cronbach's alpha was •88.

Barriers to Adolescents Seeking Help - Brief (BASH-Brief)56: This 11-item questionnaire measured psychological barriers about seeking professional help at baseline and 12-weeks post-baseline. Participants rated their agreement with a list of 11 attitudes and beliefs statements using a 6-point Likert scale. Total scores were summed (range: 11 to 66) with higher scores indicative of greater perceived barriers to seeking help. The BASH-Brief scale has demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties in adolescents.57 In the current study, participants’ scores ranged from 11 to 66 and the Cronbach's alpha was •88.

Mental Health Literacy Scale (MHLS)58: This 13-item composite scale of mental health literacy measured students’ confidence in seeking help (4 items) and their level of stigmatising attitudes towards mental illness (9 items) at baseline and 12-weeks post-baseline. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale. All items were then summed into a total score (range: 13 to 65) with higher scores indicative of greater confidence in help-seeking and lower levels of stigma. The MHLS has demonstrated good internal and test-retest reliability and has been used in school-based mental health research.59 In the current study, participants’ scores ranged from 13 to 65 and the Cronbach's alpha for the was •71.

Service outcomes – Intervention condition only

Step allocations and school counsellor follow-ups: The number of students allocated to each step of care and the number who were followed-up by the school counsellors at baseline, 6- and 12-weeks post-baseline.

Prior care with school counsellor: Students were asked at baseline to report whether they had ever had a session with a school counsellor at their school (answered yes, no, I'd rather not say). This was used to determine the number of unknown cases identified by the service.

Service use and satisfaction: Service use was measured by attrition at 6- and 12-weeks post-baseline, the number of modules accessed, and the number of check-ins completed. Satisfaction was measured using three established questionnaires.37 The first 11-item questionnaire assessed three domains of service satisfaction (enjoyment and ease of use, usefulness, and degree of comfort). The second 18-item questionnaire assessed service use barriers across three domains (technical, personal, intervention-specific). Participants were also asked to provide an overall rating of helpfulness of the service (answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “extremely unhelpful” to “extremely helpful”).

Data collection and statistical analysis

The service and study data was stored securely on the Black Dog Institute research engine. It was exported to Microsoft Excel and SPSS version 22.0 for cleaning and preparation. Group differences at baseline were compared using mixed linear or logit models incorporating a random effect of school. The primary outcome analysis was undertaken on an intention to treat basis, including all participants randomised, regardless of treatment received. The primary outcome was analysed using the baseline and 12-week post-baseline scores on the GHSQ in a mixed-effects model repeated-measures analysis, conducted in SPSS version 27.0. School was included in the analyses as a random effect to evaluate and accommodate clustering effects. Comparable methods were used for the secondary outcomes. For the secondary outcome of generalised anxiety symptoms (GAD-7), an ANCOVA was conducted controlling for baseline scores (centred at the clinical cut-off of 10) given that differences at baseline approached significance. To determine the effect of the intervention on the secondary measures of help-seeking behaviour at 12-weeks post-baseline, two logit analyses with school included as a random effect were conducted in Stata 14.2. Additional exploratory analyses were undertaken to examine the effects of age, gender, and baseline scores for help-seeking intentions, depressive symptoms, generalised anxiety symptoms, psychological distress, barriers to help-seeking, and mental health literacy on attrition rates at 12-weeks. This was conducted using logistic regression, incorporating the factors of study condition, the attributes, and the interaction. School was included as a random effect. All authors confirm that they had full access to all the data in the study and accept responsibility to submit for publication.

Role of the funding source

This work was supported by HSBC and the Graf Foundation from a non-competitive philanthropic research grant donation to the Black Dog Institute. The funders had no role in the design, execution, analyses, data interpretation, authorship or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results

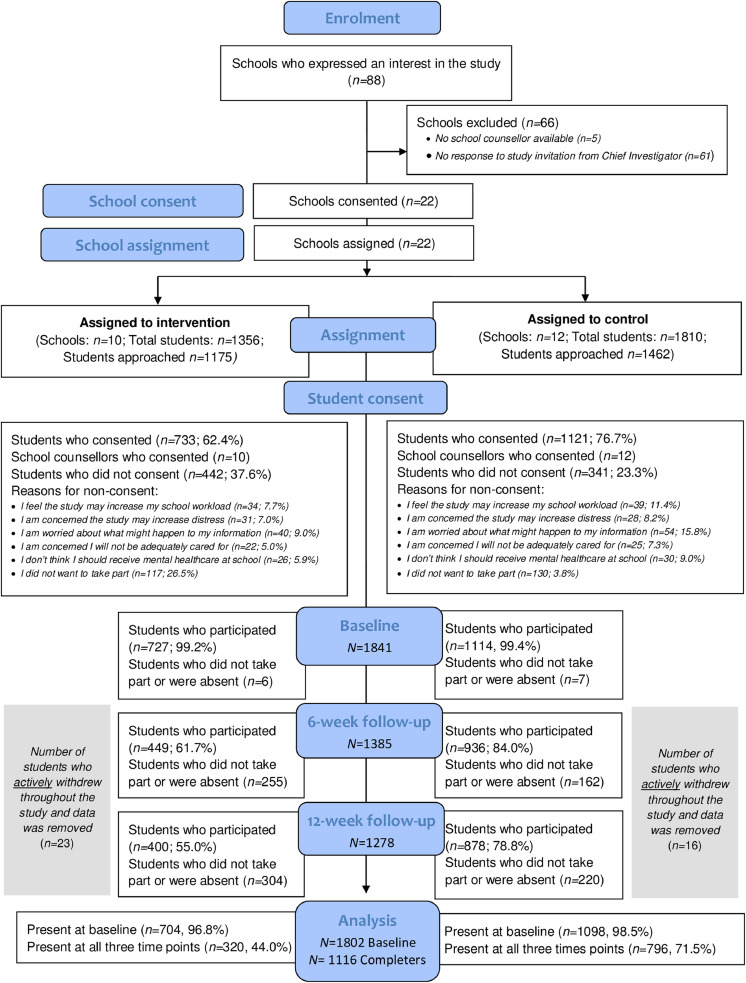

A total of 88 schools expressed interest in the study and 22 agreed to take part. There were no significant differences in the ICSEA values, total student enrolments, and gender distributions between the schools who expressed an interest in the study and those who agreed to take part (P=•152-•999). Further, no significant differences were found in the ICSEA values, total student enrolments, and gender distributions between the participating schools and all other secondary schools in New South Wales (P=•708-•956).38

Ten schools (n=9, 90•0% located in major cities) were randomised to the intervention condition and 12 schools (n=9, 75•0% located in major cities) were randomised to the control condition. A total of 1854 students consented to the study and 1841 completed baseline. Figure 3 outlines study participation, withdrawals, and attrition. The final sample characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 1 (N=1802). At baseline, the participants in the control condition reported significantly greater instances of help-seeking from adult sources than participants in the intervention condition. No other significant differences were found.

Figure 3.

CONSORT flowchart for participation, withdrawals, and attrition.

Table 1.

Baseline sample characteristics for the total sample, intervention, and control conditions (N=1802).

| Total sample(n=1802) |

Control(n=1098) |

Intervention (n=704) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | P value* | |

| Age | 14•30 | 0•87 | 14•12 | 0•89 | 14•59 | 0•75 | •088 |

| Help-seeking intentions (GHSQ) | 34•38 | 10•29 | 34•43 | 10•12 | 34•31 | 10•51 | •925 |

| Generalised anxiety (GAD-7) | 5•97 | 5•20 | 6•51 | 5•23 | 5•13 | 5•02 | •071 |

| Depression (CES-D) | 16•43 | 12•28 | 17•40 | 12•53 | 14•91 | 11•74 | •339 |

| Psychological distress (DQ5) | 11•04 | 4•94 | 11•44 | 4•94 | 10•41 | 4•88 | •201 |

| Barriers to seeking help (BASH) | 34•16 | 10•30 | 34•86 | 10•48 | 33•06 | 9•93 | •703 |

| Mental health literacy (MHLS) | 34•47 | 6•85 | 34•69 | 6•91 | 34•13 | 6•74 | •963 |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Female | 930 | 51•6 | 571 | 52•0 | 359 | 51•0 | •626 |

| Sought help from an adult for a mental health issue in the past 3 months (AHSQ) | 718 | 40•0 | 485 | 44•3 | 233 | 33•3 | •002 |

| Needed support for mental health but did not seek help from anyone in the past 3 months (AHSQ) | 325 | 18•1 | 215 | 19•6 | 110 | 15•7 | •372 |

Group differences compared using mixed linear or logit model incorporating a random effect of school. Percentages for AHSQ calculated using baseline respondents N=1796 (n=1096 in control condition, n=700 in intervention condition),

Estimated marginal means and standard errors were derived from models fitted for the primary and secondary continuous outcomes at each time point by condition. These are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean and standard error for continuous outcomes at each time point estimated from mixed effect models.

| Control |

Intervention |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6-weeks post-baseline | 12-weeks post-baseline | Baseline | 6-weeks post-baseline | 12-weeks post-baseline | |

| n=1098 | n=936 | n=878 | n=704 | n=444 | n=401 | |

| mean (SE) | mean (SE) | mean (SE) | mean (SE) | mean (SE) | mean (SE) | |

| Help-seeking intentions (GHSQ) | 34•36 (0•55) | – | 33•60 (0•59) | 34•59 (0•65) | – | 35•14 (0•73) |

| Generalised Anxiety (GAD-7) | 6•93 (0•49) | 6•22 (0•49) | 6•30 (0•50) | 5•54(0•55) | 4•96 (0•56) | 4•67 (0•56) |

| Depression (CES-DC) | 18•23 (1•31) | 17•45 (1•31) | 17•74 (1•32) | 16•28 (1•46) | 15•57 (1•48) | 15•76 (1•49) |

| Psychological Distress (DQ5) | 11•90 (0•52) | 11•23 (0•52) | 11•14 (0•52) | 10•83 (0•58) | 9•92 (0•59) | 9•77 (0•59) |

| Barriers to Seeking Help (BASH-B) | 35•16 (0•64) | – | 34•06 (0•66) | 33•06 (0•38) | – | 32•64 (0•79) |

| Mental Health Literacy (MHLS) | 34•53 (0•44) | – | 34•29 (0•46) | 34•41 (0•51) | – | 34•49 (0•57) |

The ICC for help-seeking intentions was 0•01. Participants in the intervention condition reported significantly greater improvements in their help-seeking intentions than those in the control at 12-weeks post-baseline (F(1, 1341)=4•98, P=•026). The standardised effect size was 0•10 (95%CI: -0•02 to 0•21). The test of significance for the cluster effect was significant (x2(1) = 14•61, P<•0001).

No other significant effects on the continuous secondary outcomes were found (P=•226-•977). For generalised anxiety symptoms, no universal effects were found (F(1, 1456•9)=1•03, P=•304); However, the analysis of covariance found a differential effect of study arm conditional on baseline GAD-7 score. For individuals at the cut off for clinical caseness (i.e., score of ≥10), this difference was statistically significant F(1, 29•0)=4•73, P=•038) and the standardised effect size was 0•19.

In both conditions, there was a significant reduction in the number of students who reported that they “needed help for a mental health problem but did not seek help” at 12-weeks post-baseline (Baseline: 18•1%, n=325/1795, 12-weeks post-baseline: 13•6% n=173/1271; OR: 2.08, 95%CI: 1•72–2.27, P<•0001). The reduction was significantly greater in the intervention condition (Baseline: 19•6%, n=215/1096 and 15•7%, n=110/700 for the control and intervention groups respectively; 12-weeks post-baseline: 16•1% n=141/876 and 8•1% n=32/395 for the control and intervention groups respectively; OR: 1•53, 95%CI: 1•26–2.20, P=•006). However, there was also a decline in the number of students seeking help from adults at 12-weeks post-baseline. This occurred from initially different proportions at baseline (44•2%, n=485/1096 and 33•3%, n=233/700 for the control and intervention groups respectively) and resulted in no significant difference between the conditions at 12-weeks post-baseline (28•3%, n=248/876 and 27•8%, n=110/395 respectively OR: 0•98, 95%CI: 0•47–2•04, P=•948).

Attrition

Outlined in Figure 3, 56•8% (n=400/704) of students in the intervention condition were present at 12-weeks post-baseline, compared to 79•9% (n=878/1098) in the control condition. At the individual participant level, no significant predictors of attrition were found (P=•061-•979) except for age in the control condition: Younger participants were more likely to be absent at 12-weeks post-baseline (OR: 1•44, 95%CI:1•13-1•84, P=•003). The mean difference in age was very small (MD: 0•15). However, attrition rates varied between schools. Attrition in the control schools ranged from 0% to 25•9% (median 21•2%) whereas in the intervention schools it ranged from 12•2% to 84•3% (median 31•7%). The attrition rate in the intervention condition was elevated by an external change in school policy and practice in the largest participating intervention school (baseline n=159) that resulted in its study participation rates at 12-weeks post-baseline reducing to 15•7% (n=25/159). When this school was excluded, the attrition rate in the intervention condition reduced from 43•2% (n=400/704) to 31.•% (n=375/545).

Service outcomes – intervention condition

Table 3 outlines the step allocations at baseline and 12-weeks post-baseline, alongside the number of students who required follow-up from the school counsellor. At baseline, 28•8% (n=203/704) of students screened by Smooth Sailing had moderate to severe symptoms of depression and/or anxiety. A total of 18•5% (n=130/704) required follow-up by the school counsellors. Of these, 46•9% (n=61/130) had “never” sought help from their school counsellors.

Table 3.

Step allocations, symptoms, thoughts of death/self-harm and school counsellor follow-ups at baseline and 12-weeks post-baseline among intervention participants.

| Baseline(n=704) |

12-weeks post-baseline(n=318) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Step 1 (nil to minimal) | 501 | 71•2 | 236 | 74•2 | |

| Step 2 (moderate) | 118 | 16•8 | 27 | 8•5 | |

| Step 3 (moderately severe to severe) | 85 | 12•1 | 55 | 17•3 | |

| Thoughts of death and or harming oneself | 98 | 13•9 | 52 | 13•0 | |

| Total school counsellor follow-ups | 130 | 18•5 | 63 | 19•8 | |

Overall, the mean number of psychoeducation modules accessed by intervention participants was 0•77 (SD: 1•27, range: 0-6) with two thirds (n=433, 61•5%) not completing any. The mean number of check-ins completed was 0•69 (SD:1•29) with 72•0% (n=507) not completing any.

As outlined in Table 4, most students found the service easy to use, understandable, interesting and enjoyable, although the latter were lower among those with nil to minimal symptoms. There were also some disparities in the other domains of satisfaction. In general, students at the highest step reported greater satisfaction with the service. Nearly all students with symptoms were comfortable with the school counsellor follow-ups and two thirds would use the service again in the future. However, less than half felt that the service helped them in their everyday life or that the service helped them to feel in control of their feelings.

Table 4.

Service satisfaction at 12-weeks post-baseline stratified by baseline step allocation (n=392).

| Step 1 (n=279) |

Step 2 (n=71) |

Step 3 (n=42) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Enjoyment and ease of use | I found Smooth Sailing easy to use | 262 | 93•9 | 65 | 91•5 | 41 | 97•6 |

| Smooth Sailing was easy to understand | 248 | 88•9 | 62 | 87•3 | 38 | 90•5 | |

| I thought Smooth Sailing was interesting | 191 | 68•5 | 52 | 73•2 | 36 | 85•7 | |

| I enjoyed using Smooth Sailing | 181 | 64•9 | 50 | 70•4 | 33 | 78•6 | |

| Usefulness | I would tell a friend to use Smooth Sailing if I thought they needed to | 184 | 65•9 | 50 | 70•4 | 32 | 76•2 |

| I would use Smooth Sailing again in the future | 140 | 50•2 | 32 | 45•1 | 26 | 61•9 | |

| Smooth Sailing helped me to feel in control of my feelings | 141 | 50•5 | 29 | 40•8 | 21 | 50•0 | |

| The skills I learned from Smooth Sailing helped me a lot in everyday life | 115 | 41•2 | 28 | 39•4 | 21 | 50•0 | |

| Degree of comfort with service requirements | I understood I may be followed-up by the school counsellor and was okay with this | 198 | 71•0 | 61 | 85•9 | 39 | 92•9 |

| I felt comfortable providing my email address | 209 | 74•9 | 51 | 71•8 | 34 | 81•0 | |

| I felt comfortable providing my mobile phone number | 133 | 47•7 | 36 | 50•7 | 27 | 64.3 | |

Students reported that personal barriers including disinterest, forgetfulness, mismatch with needs, and being time poor inhibited their use of the service (see Table 5). In general, students at step 1 reported far fewer barriers to service use than those at step 2 and above. Interestingly, one third of those at the highest step reported that Smooth Sailing was “not what they needed”, despite having elevated symptoms. Technical barriers related to accessibility were also more common among students at the highest step. Overall, participants gave the service a mean helpfulness rating of 3•24 out of 5 (SD: 0•88, n=374, range: 1-5).

Table 5.

Barriers to service use at 12-weeks post-baseline stratified by baseline step allocation (n=390).

| Step 1 (n=277) |

Step 2 (n=71) |

Step 3 (n=42) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n) | % | Yes (n) | % | Yes (n) | % | ||

| Personal | I couldn't be bothered to use Smooth Sailing | 117 | 42•2 | 41 | 57•7 | 19 | 45•2 |

| I forgot about Smooth Sailing | 116 | 41•9 | 34 | 47•9 | 17 | 40•5 | |

| Smooth Sailing wasn't what I needed | 98 | 35•4 | 30 | 42•3 | 14 | 33•3 | |

| I didn't have time to use Smooth Sailing | 82 | 29•6 | 35 | 49•3 | 23 | 54•8 | |

| I didn't want the school counsellor to know my feelings | 32 | 11•6 | 17 | 23•9 | 17 | 40•5 | |

| I was worried about privacy of data | 37 | 13•4 | 8 | 11•3 | 12 | 28•6 | |

| I felt too worried or down to use Smooth Sailing | 8 | 2•9 | 10 | 14•1 | 17 | 40•5 | |

| Intervention specific | Service content took too long to read | 49 | 17•7 | 26 | 36•6 | 9 | 21•4 |

| Check-ins took too long to complete | 52 | 18•8 | 18 | 25•4 | 7 | 16•7 | |

| Service used too much phone data | 21 | 7•6 | 10 | 14•1 | 9 | 21•4 | |

| I didn't trust Smooth Sailing | 23 | 8•3 | 7 | 9•9 | 7 | 16•7 | |

| Smooth Sailing made me feel worse | 19 | 6•9 | 4 | 5•6 | 5 | 11•9 | |

| Text was too small and hard to read on phone | 15 | 5•4 | 7 | 9•9 | 2 | 4•8 | |

| Technical | I forgot how to access Smooth Sailing | 29 | 10•5 | 16 | 22•5 | 12 | 28•6 |

| My Internet connection didn't work | 28 | 10•1 | 16 | 22•5 | 12 | 28•6 | |

| I had trouble logging into the service website | 16 | 5•8 | 8 | 11•3 | 9 | 21•4 | |

| Service website took too long to load | 17 | 6•1 | 10 | 14•1 | 5 | 11•9 | |

| I didn't have a phone or computer to use | 12 | 4•3 | 5 | 7•0 | 9 | 21•4 | |

Discussion

The current study investigated the potential of a web-based, stepped-care service model for improving help-seeking intentions for general mental health problems when delivered universally to secondary school students in New South Wales, Australia. The findings suggest that the Smooth Sailing service led to small improvements in students’ intentions to seek help for their mental health problems and may have also reduced the number who needed support for their mental health but were not actively seeking help. The significant effect on generalised anxiety symptoms among students with high baseline scores also favoured the Smooth Sailing service. Although comparable to other help-seeking39,40 and school-based mental health interventions60, the primary effect size in the current study was small relative to conventions, and the secondary effects would not survive adjustments for multiple testing. Attrition in the intervention condition was higher than the control condition, and there were no significant effects for other important mental health outcomes. While the threshold for a meaningful or practical effect for universal school-based mental health interventions is unclear61, the results do not provide unequivocal support for the implementation of the Smooth Sailing service in its current form. Instead, the findings of this study may be used to guide the process of service refinement and future evaluations.

In both conditions, the rates of help-seeking from adults declined at 12-weeks post-baseline. Many studies have indicated that the relationship between help-seeking intentions and behaviour among youth is indeed modest, and that intentions do not always correlate with symptoms or behaviour.30 Our findings are consistent with Batterham et al.62, who demonstrated that online mental health screening did not increase help-seeking from professional sources. As explained by Rickwood and colleagues’ help-seeking model30, young people must have an awareness of their need for help and trusted sources of adult support readily available for help-seeking intentions to translate into behaviour change. The Cycle of Avoidance model63 further stipulates that adolescents need to meet a personal threshold of distress and disruption before they proactively seek help, and the initial response to mental distress involves accommodating or denying illness rather than resolving it, even when symptoms become severe. Thus, the clinical threshold for intervention is more conservative and typically inconsistent with that held by the adolescent. This notion is supported by the Health Belief Model64 where the uptake of professional help is determined by the perceived susceptibility to illness, severity of consequences, benefits of treatment, barriers to action, and one's general health motivation, which is challenged by adolescents’ desire for autonomy and independence.65 Therefore, the transition from recognising an issue, accepting the need for help, developing the intention to seek help, and actual help-seeking is a complex, circular process that may take more time than the current study observed.

As many students in the current study reported that the service was not what they needed, despite the presence of symptoms, the effects of the intervention may be strengthened by providing students with more specific feedback on their symptoms, a benchmark for comparison with peer-norms, and the health and wellbeing consequences of prolonged distress. Wellbeing measures, rather than diagnostic symptom scales, may also lead to greater help-seeking.66 Visual representations of symptom change67, collated with input from trusted adults such as parents7,68 may further persuade a young person of their need for help. This enhanced feedback should be displayed in a confidential manner, given that symptomatic students reported concerns about data privacy. Future studies would also benefit from asking students about their perceptions of their need for mental healthcare and examining its impact on primary outcomes.7

As outlined, the decline in help-seeking from adults was also likely to have been impacted by the availability of trusted adults and other systemic and structural barriers that inhibit access to professional care.6,9 The baseline rates of help-seeking from adult sources were consistent with population norms.1,9 While the reduction in adult help-seeking behaviour may have been caused by a weakened support network or negative past experiences, a plausible explanation may be found in the timing of the study. Baseline data was collected in Term 1 of the school year, after an extended period of school holidays. During this time, students may have had increased availability, motivation, and emotional capacity to disclose concerns to trusted adults and seek professional help outside of the school setting. Help-seeking behaviour may naturally wane over the course of the school year as adolescents and their families become time poor, logistical barriers increase, and adolescents may refuse help.6,7 In this way, the findings argue for a greater examination of the impact of systemic school factors on students' help-seeking for mental health. Recent research has found that school size and location has impacted help-seeking among youth69, and may suggest that other structural aspects, such as school culture and competing priorities may impede students’ abilities to seek professional help during the school term. This may signify support for greater onsite access to health professionals70 who can provide immediate care. Advances in telehealth due to COVID may enable this.71 This study may also have been impacted by positive trial effects such that study participation may have generated an impetus among students to explore other formal help-seeking options that were not explicitly measured or recognised by this sample. On the contrary, a negative observer effect may have created the illusion of a help-seeking “safety net” whereby students felt they were getting the help they needed simply from the study activities. Future studies would benefit from untangling these effects to determine unintended consequences and associated harms.

Key considerations for service improvements

The results indicate that designing and delivering a universal mental health service that meets the needs of all secondary school students is a significant challenge. Further, meaningful effects can be harder to ascertain in universal interventions as clinically important change in students with symptoms is likely to be different to that in students with no symptoms.72,73 Nearly one in five students screened by Smooth Sailing required follow-up for their anxiety, depression or suicidality and many were unknown to school counselling services. This is consistent with the pilot study35 and confirms that Smooth Sailing may capture students with unmet mental health needs. However, attrition in the intervention condition was higher than the control. Service satisfaction and barriers to use also varied with symptom severity. This complicates decision-making on improvements but implies that aspects of the service may be onerous.

Consistent with the pilot study, many of the students reported that time, forgetfulness, and low motivation were barriers to service use, despite prior enhancements to address these. Given that up to 20% of individuals with symptoms of depression and anxiety may spontaneously recover in three months74, and the likelihood of remission is higher in children and adolescents, the service model could be modified to include an initial six-week period of “watchful waiting” where no individual intervention is provided.31 Instead, schools receive an evidence-based, universal, school-wide mental health program with a preventative focus.60 This approach may help to foster a positive school culture towards mental health, broaden the appeal of the service to non-symptomatic youth, and reduce symptoms in those who are unwell. This is particularly pertinent given over a third of the sample reported that the current service model was not what they needed. Aligning the service with the New South Wales educational curriculum and allocating supervised class time for module completions may also overcome the barriers related to low motivation, forgetfulness, and Internet accessibility.75 Using incentives, such as integrating module completion with broader school reward systems, may also help to increase motivation, which in turn may improve uptake, engagement, and effects.

Interestingly, over 90% of the students who required follow-up from a school counsellor reported that they were comfortable with this feature, yet 40% said they did not want their school counsellor to know their feelings. This is consistent with the declines in actual help-seeking behaviour. This may suggest that the process of mandated follow-up was acceptable to symptomatic students but did not increase their comfort with school counselling services in general. As perceived confidentiality and inability to trust an unknown person is a barrier to professional care for youth6, the service may be improved by familiarising students with their school counsellors prior to service uptake and upskilling other trusted school staff to connect students with care. This may also improve initial consent rates for the service by addressing students’ reluctance to receive mental healthcare at their school.

Although the current trial did not aim to examine treatment effects, over 40% of the symptomatic participants reported that they felt too worried or down to use Smooth Sailing. Some students (7%) said the service made them feel worse. It is likely that schools and health professionals may wish to have these aspects of the service addressed to minimise the risk of overdiagnosis and treatment related harms. The service may benefit from embedding low intensity, single session interventions that are targeted to youth experiencing the motivational detriments and heightened worry and sadness that characterise anxiety and depression.76 Given the role that parents play in promoting help-seeking and facilitating access to services7, parents could also be upskilled to champion the use of Smooth Sailing among symptomatic youth.

Limitations

The current trial was strengthened by its fidelity, pragmatic design, and the representativeness of the participating secondary schools. However, the low conversion rate (1 in 4) of consenting schools from those who expressed interest suggests a reluctance and inability of many schools to participate in intensive mental health service research of this kind. Further, while students were not informed of their school's allocation, the more intensive nature of the intervention condition may have led to fewer students being willing to consent and take part for the duration of the trial. The reported mismatch of the service with students’ perceived needs may have also contributed to this, as most of the intervention participants were not experiencing poor mental health. However, the variation in attrition across schools indicates that school context is likely to be an influential factor in students’ uptake and engagement with Smooth Sailing. Future studies may benefit from employing additional strategies to retain participants across schools, as well as different study designs (e.g., multiphase optimisation strategy, Bayesian approaches, case studies) to discern trial effects from intervention effects and mitigate reasons for drop-out. A major strength and commendation for the current trial is the measurement and inclusion of minors with suicidal ideation. However, this created a challenge for the trial design due to the ethics requirements. As such, we were not able to compare this outcome across the two conditions. This questionnaire may have also had a priming effect or contributed to an intervention effect, such that individuals who received the Smooth Sailing service were motivated to seek help or respond to the measures differently when compared to those in the control. Future studies may benefit from including more culturally and linguistically diverse populations including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. Measures of socio-economic status and other accessibility factors will also help to better understand the limitations of the service for improving help-seeking behaviour. Supplementing self-report scales with input from clinicians, parents, and teachers may help to validate the findings. Future research should also examine the long-term impacts of Smooth Sailing as the current trial period was relatively short, particularly for a universal sample of whom most did not develop mental health problems and had no need to seek help. A future health economics analysis will also determine the cost benefits of the Smooth Sailing service model.

Conclusion

This is the first randomised controlled trial to indicate a small but positive effect on help-seeking intentions for mental health from a web-based mental health service that integrates screening, with stepped intervention and iCBT, for universal delivery in the school setting. The findings suggest that students’ intentions to seek help for mental health problems may be improved by this type of service model; although, there were no improvements in actual help-seeking from adult sources and other important mental health outcomes at 12-weeks post-baseline. The service appeared useful for identifying students with unmet mental health needs, but a range of barriers impacted service uptake, engagement, and retention among students. Taken together, findings highlight the need for various service improvements. This may have broader implications for the application of web-based mental health services in school settings, particularly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Given that a small effect size may mask a ‘high potential’ approach60,61, an improved version of the Smooth Sailing service may hold significant promise for strengthening the provision of mental healthcare in Australian secondary schools.77 Future trials, which include a threshold for clinically meaningful significance, will help to determine this.

Contributors

BOD: Conception, recruitment, data collection, analysis, interpretation, knowledge, authorship and editing.

MSK: Conception, recruitment, data collection, analysis, interpretation, knowledge, authorship and editing.

CK: Conception, recruitment, data collection, data preparation, analysis, interpretation, authorship and editing.

AJM: Group assignment, data preparation, analysis, interpretation, authorship and editing.

MRA: Recruitment, data collection, data preparation, interpretation, authorship and editing.

MA: Recruitment, data collection, interpretation, authorship and editing.

BP: Recruitment, data collection, interpretation, authorship and editing.

AWS: Interpretation, knowledge, authorship and editing.

MT: Interpretation, knowledge, authorship and editing.

NC: Conception, interpretation, knowledge, authorship and editing.

SB: Interpretation, knowledge, authorship and editing.

HC: Conception, interpretation, knowledge, authorship and editing.

Data sharing

The data collected and analysed in the current trial is not currently available to researchers outside of the approved team due to constraints placed on the project by the various ethics bodies. Additional related project documents are currently available from the web-based Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Dr O'Dea and Professor Helen Christensen reports philanthropic non-competitive research grants from HSBC and the Graf Foundation during the conduct of the trial. Dr O'Dea reports speaker fees and travel reimbursements from the New South Wales and Queensland Departments of Education, paid to the Black Dog Institute for educational training seminars, that were outside the submitted work. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Black Dog Institute IT team who supported the build and implementation of the web-based service and research trial. The authors would like to acknowledge the Trial Steering Committee for their oversight, guidance, and support throughout the design and evaluation of the Smooth Sailing service model.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100178.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J. 2015. The mental health of children and adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das JK, Salam RA, Lassi ZS. Interventions for Adolescent Mental Health: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(4S):S49–S60. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoover S, Bostic J. Schools As a Vital Component of the Child and Adolescent Mental Health System. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;72(1):37–48. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Platt IA, Kannangara C, Carson J, Tytherleigh M. Heuristic assessment of psychological interventions in schools (HAPI Schools) Psychol Sch. 2021:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(1):113. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radez J, Reardon T, Creswell C, Lawrence PJ, Evdoka-Burton G, Waite P. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Euro Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30(2):183–211. doi: 10.1007/s00787-019-01469-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schnyder N, Lawrence D, Panczak R. Perceived need and barriers to adolescent mental health care: agreement between adolescents and their parents. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;29:e60. doi: 10.1017/S2045796019000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnyder N, Panczak R, Groth N, Schultze-Lutter F. Association between mental health-related stigma and active help-seeking: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(4):261–268. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.189464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schnyder N, Sawyer MG, Lawrence D, Panczak R, Burgess P, Harris MG. Barriers to mental health care for Australian children and adolescents in 1998 and 2013-2014. ANZJP. 2020;54(10):1007–1019. doi: 10.1177/0004867420919158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson M, Werner-Seidler A, King C, Gayed A, Harvey SB, O'Dea B. Mental Health Training Programs for Secondary School Teachers: A Systematic Review. School Ment Health. 2019;11:489–508. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fazel M, Hoagwood K, Stephan S, Ford T. Mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):377–387. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Alegría M. School mental health resources and adolescent mental health service use. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2013;52(5):501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husky MM, Kaplan A, McGuire L, Flynn L, Chrostowski C, Olfson M. Identifying adolescents at risk through voluntary school-based mental health screening. J Adolesc. 2011;34(3):505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allison VL, Nativio DG, Mitchell AM, Ren D, Yuhasz J. Identifying symptoms of depression and anxiety in students in the school setting. J Sch Nurs. 2014;30(3):165–172. doi: 10.1177/1059840513500076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowdy E, Furlong M, Raines TC. Enhancing School-Based Mental Health Services With a Preventive and Promotive Approach to Universal Screening for Complete Mental Health. J Educ Psychol Consult. 2015;25(2-3):178–197. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore SA, Widales-Benitez O, Carnazzo KW, Kim EK, Moffa K, Dowdy E. Conducting Universal Complete Mental Health Screening via Student Self-Report. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2015;19(4):253–267. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dowdy E, Ritchey K, Kamphaus RW. School-Based Screening: A Population-Based Approach to Inform and Monitor Children's Mental Health Needs. School Ment Health. 2010;2(4):166–176. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9036-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore SA, Mayworm AM, Stein R, Sharkey JD, Dowdy E. Languishing students: Linking complete mental health screening in schools to Tier 2 intervention. J Appl Sch Psychol. 2019;35(3):257–289. doi: 10.1080/15377903.2019.1577780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruns EJ, Pullmann MD, Nicodimos S. Pilot Test of an Engagement, Triage, and Brief Intervention Strategy for School Mental Health. School Ment Health. 2018;11:148–162. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood BJ, McDaniel T. A preliminary investigation of universal mental health screening practices in schools. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;112 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruhn AL, Woods-Groves S., Huddle S. A Preliminary Investigation of Emotional and Behavioral Screening Practices in K–12 Schools. Educ Treat Children. 2014;37(4):611–634. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer MS, Rosenthal A, Bolden KA. Psychosis screening in schools: Considerations and implementation strategies. Early Interv Psychia. 2020;14(1):130–136. doi: 10.1111/eip.12858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soneson E, Howarth E, Ford T. Feasibility of School-Based Identification of Children and Adolescents Experiencing, or At-risk of Developing, Mental Health Difficulties: a Systematic Review. Prev Sci. 2020;21(5):581–603. doi: 10.1007/s11121-020-01095-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siu AL. Screening for Depression in Children and Adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3) doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson JK, Ford T, Soneson E. A systematic review of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of school-based identification of children and young people at risk of, or currently experiencing mental health difficulties. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):9–19. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718002490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore SA, Dowdy E, Hinton T, DiStefano C, Greer FW. Moving Toward Implementation of Universal Mental Health Screening by Examining Attitudes Toward School-Based Practices. Behav Disord. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1177/0198742920982591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Dea B, King C, Subotic-Kerry M, O'Moore K, Christensen H. School Counselors’ Perspectives of a Web-Based Stepped Care Mental Health Service for Schools: Cross-Sectional Online Survey. JMIR Ment Health. 2017;4(4):e55. doi: 10.2196/mental.8369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subotic-Kerry M, King C, O'Moore K, Achilles M, O'Dea B. General Practitioners’ Attitudes Toward a Web-Based Mental Health Service for Adolescents: Implications for Service Design and Delivery. JMIR Hum Factors. 2018;5(1):e12. doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.8913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Dea B, Leach C, Achilles M, King C, Subotic-Kerry M, O'Moore K. Parental attitudes towards an online, school-based, mental health service: implications for service design and delivery. Adv Ment Health. 2019;17(2):146–160. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rickwood D, Deane FP, Wilson CJ, Ciarrochi J. Young people's help-seeking for mental health problems. AeJAMH. 2005;4(3):218–251. [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Straten A, Seekles W, van 't Veer-Tazelaar NJ, Beekman AT, Cuijpers P. Stepped care for depression in primary care: what should be offered and how? Med J Aust. 2010;192(11 Suppl):S36–S39. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDermott B, Baigent M, Chanen A. BeyondBlue; Melbourne: 2010. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Depression in adolescents and young adults. [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Straten A, Hill J, Richards DA, Cuijpers P. Stepped care treatment delivery for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2014;45(2):231–246. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rapee RM, Lyneham HJ, Wuthrich V. Comparison of stepped care delivery against a single, empirically validated Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy program for youth with anxiety: A randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2017;56(10):841–848. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Dea B, King C, Subotic-Kerry M, Achilles MR, Cockayne N, Christensen H. Smooth Sailing: A Pilot Study of an Online, School-Based, Mental Health Service for Depression and Anxiety. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:574. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pretorius C, Chambers D, Coyle D. Young People's Online Help-Seeking and Mental Health Difficulties: Systematic Narrative Review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(11):e13873. doi: 10.2196/13873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Dea B, King C, Subotic-Kerry M. Evaluating a Web-Based Mental Health Service for Secondary School Students in Australia: Protocol for a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(5):e12892. doi: 10.2196/12892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority. National Report on Schooling Data Portal - School Profiles 2008-2019. Australia: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority; 2019.

- 39.Xu Z, Huang F, Kösters M. Effectiveness of interventions to promote help-seeking for mental health problems: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(16):2658–2667. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Brewer JL. A systematic review of help-seeking interventions for depression, anxiety and general psychological distress. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clarke AM, Kuosmanen T, Barry MM. A systematic review of online youth mental health promotion and prevention interventions. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(1):90–113. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lubman DI, Cheetham A, Sandral E. Twelve-month outcomes of MAKINGtheLINK: A cluster randomized controlled trial of a school-based program to facilitate help-seeking for substance use and mental health problems. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;18 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kelly AB, Halford WK. Responses to ethical challenges in conducting research with Australian adolescents*. Aust J Psych. 2007;59:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calear AL, Christensen H, Mackinnon A, Griffiths KM, O'Kearney R. The YouthMood Project: A cluster randomized controlled trial of an online cognitive behavioral program with adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(6):1021–1032. doi: 10.1037/a0017391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spence SH, Donovan CL, March S. A randomized controlled trial of online versus clinic-based CBT for adolescent anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(5):629–642. doi: 10.1037/a0024512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Ciarrochi JV, Rickwood D. Measuring help seeking intentions: Properties of the General Help seeking Questionnaire. Can J Couns. 2005;39(1):15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Divin N, Harper P, Curran E, Corry D, Leavey G. Help-Seeking Measures and Their Use in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Adolesc Res Rev. 2018;3(1):113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mossman SA, Luft MJ, Schroeder HK. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder: Signal detection and validation. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(4):227–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roberts RE, Andrews JA, Lewinsohn PM, Hops H. Assessment of depression in adolescents using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Psychol Assess. 1990;2(2):122–128. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fendrich M, Weissman MM, Warner V. Screening for depressive disorder in children and adolescents: validating the center for epidemiologic studees depression scale for children. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131(3):538–551. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Batterham PJ, Sunderland M, Carragher N, Calear AL, Mackinnon AJ, Slade T. The Distress Questionnaire-5: Population screener for psychological distress was more accurate than the K6/K10. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;71:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Batterham PJ, Sunderland M, Slade T, Calear AL, Carragher N. Assessing distress in the community: psychometric properties and crosswalk comparison of eight measures of psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2018;48(8):1316–1324. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717002835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Werner-Seidler A, Huckvale K, Larsen ME. A trial protocol for the effectiveness of digital interventions for preventing depression in adolescents: The Future Proofing Study. Trials. 2020;21(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3901-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuhl J, Jarkon-Horlick L, Morrissey R. Measuring barriers to help-seeking behavior in adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 1997;26(6):637–650. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lubman DI, Cheetham A, Jorm AF. Australian adolescents' beliefs and help-seeking intentions towards peers experiencing symptoms of depression and alcohol misuse. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):658. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4655-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O'Connor M, Casey L. The Mental Health Literacy Scale (MHLS): A new scale-based measure of mental health literacy. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229(1):511–516. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vella SA, Swann C, Batterham M. Ahead of the game protocol: a multi-component, community sport-based program targeting prevention, promotion and early intervention for mental health among adolescent males. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):390. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Werner-Seidler A, Perry Y, Calear AL, Newby JM, Christensen H. School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51(Supplement C):30–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pogrow S. How Effect Size (Practical Significance) Misleads Clinical Practice: The Case for Switching to Practical Benefit to Assess Applied Research Findings. The American Statistician. 2019;73(sup1):223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Sunderland M, Carragher N, Brewer JL. Online screening and feedback to increase help-seeking for mental health problems: population-based randomised controlled trial. BJPsych Open. 2016;2(1):67–73. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.001552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Biddle L, Donovan J, Sharp D, Gunnell D. Explaining non-help-seeking amongst young adults with mental distress: a dynamic interpretive model of illness behaviour. Sociol Health Illn. 2007;29(7):983–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O'Connor PJ, Martin B, Weeks CS, Ong L. Factors that influence young people's mental health help-seeking behaviour: a study based on the Health Belief Model. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(11):2577–2587. doi: 10.1111/jan.12423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aguirre Velasco A, Cruz ISS, Billings J, Jimenez M, Rowe S. What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):293. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choi I, Milne DN, Deady M, Calvo RA, Harvey SB, Glozier N. Impact of Mental Health Screening on Promoting Immediate Online Help-Seeking: Randomized Trial Comparing Normative Versus Humor-Driven Feedback. JMIR Ment Health. 2018;5(2):e26. doi: 10.2196/mental.9480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Delgadillo J, de Jong K, Lucock M. Feedback-informed treatment versus usual psychological treatment for depression and anxiety: a multisite, open-label, cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(7):564–572. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maiuolo M, Deane FP, Ciarrochi J. Parental Authoritativeness, Social Support and Help-seeking for Mental Health Problems in Adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(6):1056–1067. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-00994-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Doan N, Patte KA, Ferro MA, Leatherdale ST. Reluctancy towards Help-Seeking for Mental Health Concerns at Secondary School among Students in the COMPASS Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19):7128. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Newcomb D, Johnson H. GPs in schools: what do students and staff want from a school-based healthcare service in Queensland. Int J Integr Care. 2021;20(3):124. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mayworm AM, Lever N, Gloff N. School-based telepsychiatry in an urban setting: Efficiency and satisfaction with care. Telemed J E Health. 2021;26(4):446–454. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Keefe RSE, Kraemer HC, Epstein RS. Defining a clinically meaningful effect for the design and interpretation of randomized controlled trials. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(5-6 Suppl A) 4S-19S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bakker A, Cai J, English L, Kaiser G, Mesa V, Van Dooren W. Beyond small, medium, or large: points of consideration when interpreting effect sizes. Educ Stud Math. 2019;102(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Whiteford HA, Harris MG, McKeon G. Estimating remission from untreated major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;43(8):1569–1585. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Calear AL, Christensen H, Mackinnon A, Griffiths KM. Adherence to the MoodGYM program: outcomes and predictors for an adolescent school-based population. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1-3):338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]