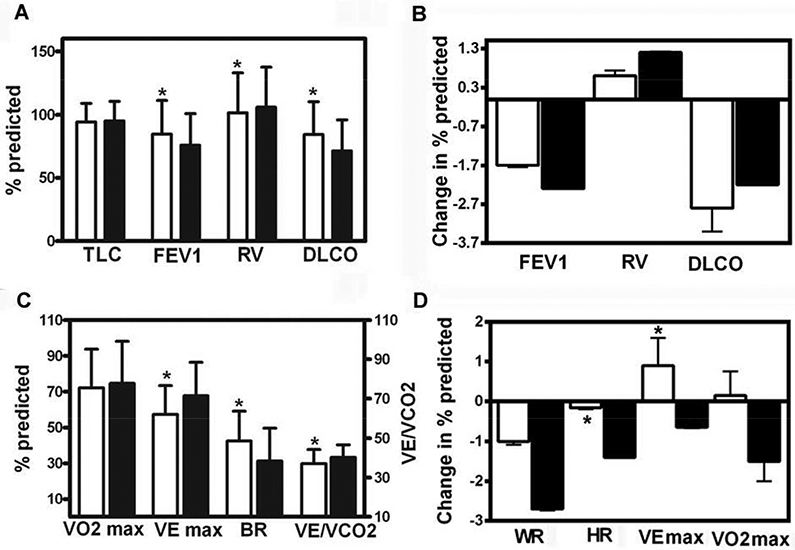

Figure 2.

Panel A: Pulmonary function data in 94 TSC-LAM (white bars) and 460 sporadic LAM (black bars) patients obtained at the time of the first visit to NIH. Overall TSC-LAM patients have significantly higher FEV1 and DLCO and lower RV than sporadic LAM patients. Panel B: Yearly changes in percent-predicted FEV1, RV, and DLCO, in 73 patients with TSC-LAM (white bars) and 319 patients with sporadic LAM (black bars) followed for over five years, expressed as mean ±SEM. No statistically significant differences were observed between TSC-LAM and sporadic LAM patients. Panel C: Initial cardiopulmonary exercise data in 76 TSC-LAM (white bars) and 340 sporadic LAM patients (black bars) obtained at the time of the first visit to NIH. TSC-LAM patients have significantly higher BR and lower VE max and lower VE/VCO2 than sporadic LAM patients. Panel D: Yearly changes in exercise variables in 60 TSC-LAM (white bars) and 236 sporadic LAM patients (black bars) followed for approximately four years, expressed as mean ±SEM. There was a statistically significant difference in the rates of change in peak heart rate and peak minute ventilation between TSC-LAM and sporadic LAM patients.

Abbreviations used are: TLC: total lung capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in the first second; RV: residual volume; DLCO: diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide; VE max: minute ventilation at peak exercise; VO2 max: peak oxygen consumption; HR: heart rate; BR: breathing reserve; VE/VCO2: ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide. * p< 0.05, significantly different from sporadic LAM patients.