Abstract

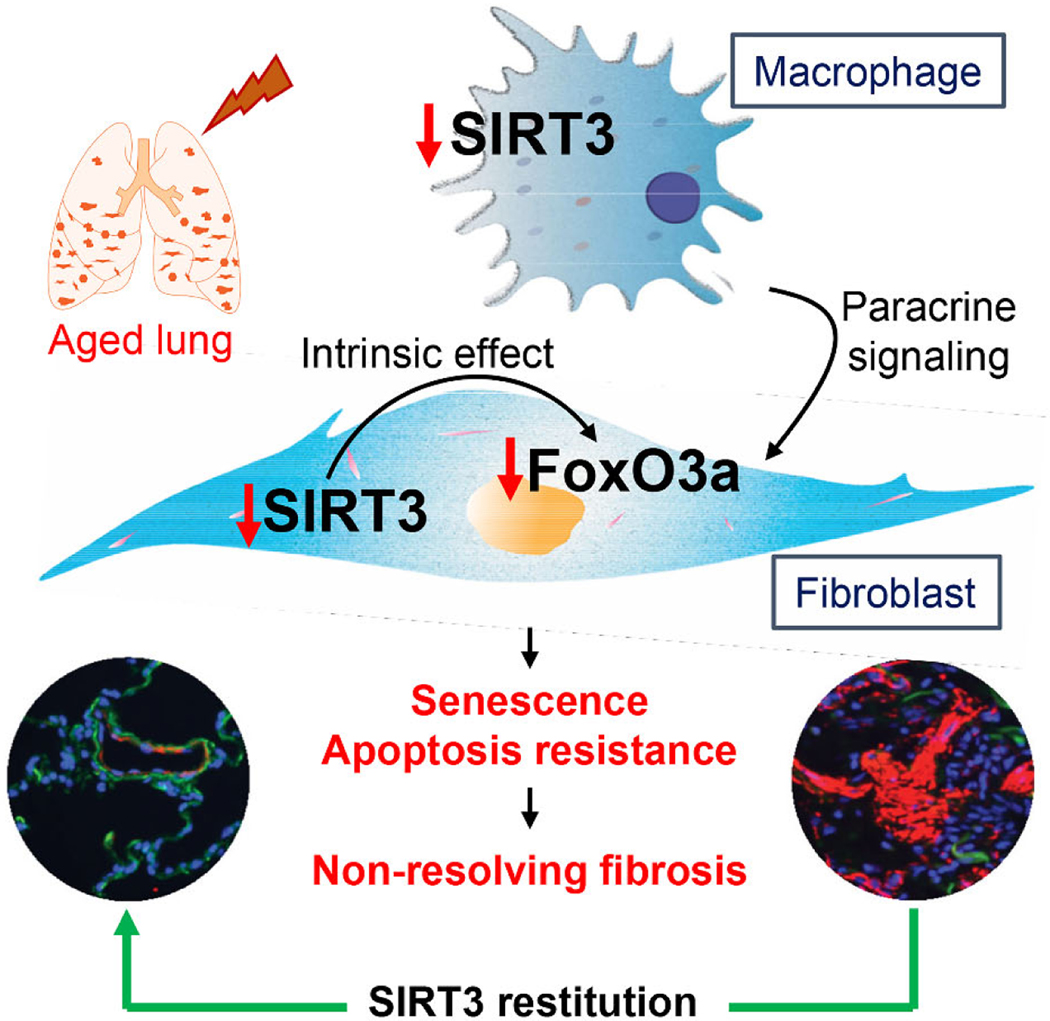

Aging is a risk factor for progressive fibrotic disorders involving diverse organ systems, including the lung. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, an age-associated degenerative lung disorder, is characterized by persistence of apoptosis-resistant myofibroblasts. In this report, we demonstrate that sirtuin-3 (SIRT3), a mitochondrial deacetylase, is downregulated in lungs of IPF human subjects and in mice subjected to lung injury. Over-expression of the SIRT3 cDNA via airway delivery restored capacity for fibrosis resolution in aged mice, in association with activation of the forkhead box transcription factor, FoxO3a, in fibroblasts, upregulation of pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, and recovery of apoptosis susceptibility. While transforming growth factor-β1 reduced levels of SIRT3 and FoxO3a in lung fibroblasts, cell non-autonomous effects involving macrophage secreted products were necessary for SIRT3-mediated activation of FoxO3a. Together, these findings reveal a novel role of SIRT3 in pro-resolution macrophage functions that restore susceptibility to apoptosis in fibroblasts via a FoxO3a-dependent mechanism.

Fibrotic disorders span across multiple organs systems1. A consistent pathological finding in these disorders is the accumulation of activated myofibroblasts and deposition of mature extracellular matrix (ECM) in association with impaired capacity for epithelial cell regeneration2. In most species and across organs in humans, regeneration and fibrosis are antagonistically and inversely related. While impaired regeneration leads to fibrosis, a skewing of the tissue repair response to fibrosis may reciprocally dampen latent regenerative capacity1,3–5. Aging is known to be associated with impaired regenerative capacity, and it is also an established risk factor for human fibrotic disorders6–8. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive, age-related lung disorder that is associated with high morbidity and mortality2. The incidence of IPF increases from 2.6 new cases per 100,000 persons among individuals less than 45 years of age to 19.3 per year among the 55–64 years old age group9. There is growing interest in how the biology of aging contributes to risk and progression of age-related fibrosis, including IPF10,11.

The biology of aging has advanced in recent years and, in addition to the identification of molecular and cellular hallmarks, several genes have been linked to lifespan12. Multiple studies have implicated two genes, sirtuin-3 (Sirt3) and the forkhead box (Fox) transcription factor, FoxO3a, genes with longevity13–16. Members of the SIRT and Fox families are evolutionarily conserved from bacteria to mammals. Sirtuins are NAD+ dependent histone deacetylases with different subcellular localizations and with broad activities on target proteins17,18. SIRT3 is localized to mitochondria19. SIRT3 ablation leads to accelerated aging, cancer and age-related neurodegenerative diseases20–22. FoxO3a has a conserved DNA binding domain that serves multiple functions as tumor suppressor genes23,24. FoxO3a regulates the transcription of genes involved in apoptosis, proliferation, oxidative stress, metabolism and differentiation25,26.

While most published reports of putative anti-fibrotic therapeutic strategies have primarily focused on the initiation and development of lung fibrosis27–30, studies exploring pro-regenerative or anti-fibrotic mechanisms on the resolution and reversal of lung fibrosis are relatively lacking31. We propose that aging biology can be leveraged to develop novel therapeutic strategies that target cellular plasticity and fate in established fibrosis. In this study, we report that SIRT3 is downregulated in IPF fibroblasts and bleomycin-induced lung injury in aged mice with persistent, non-resolving fibrosis; restoring SIRT3 expression in the late reparative phase reverses established lung fibrosis. Furthermore, this study reveals that the pro-resolution effect of SIRT3 is mediated by macrophage-derived paracrine signaling that activates FoxO3a in fibroblasts, upregulates pro-apoptotic Bcl2 family proteins, and induces apoptotic cell death essential for fibrosis resolution.

RESULTS

SIRT3 expression is decreased in human IPF lungs.

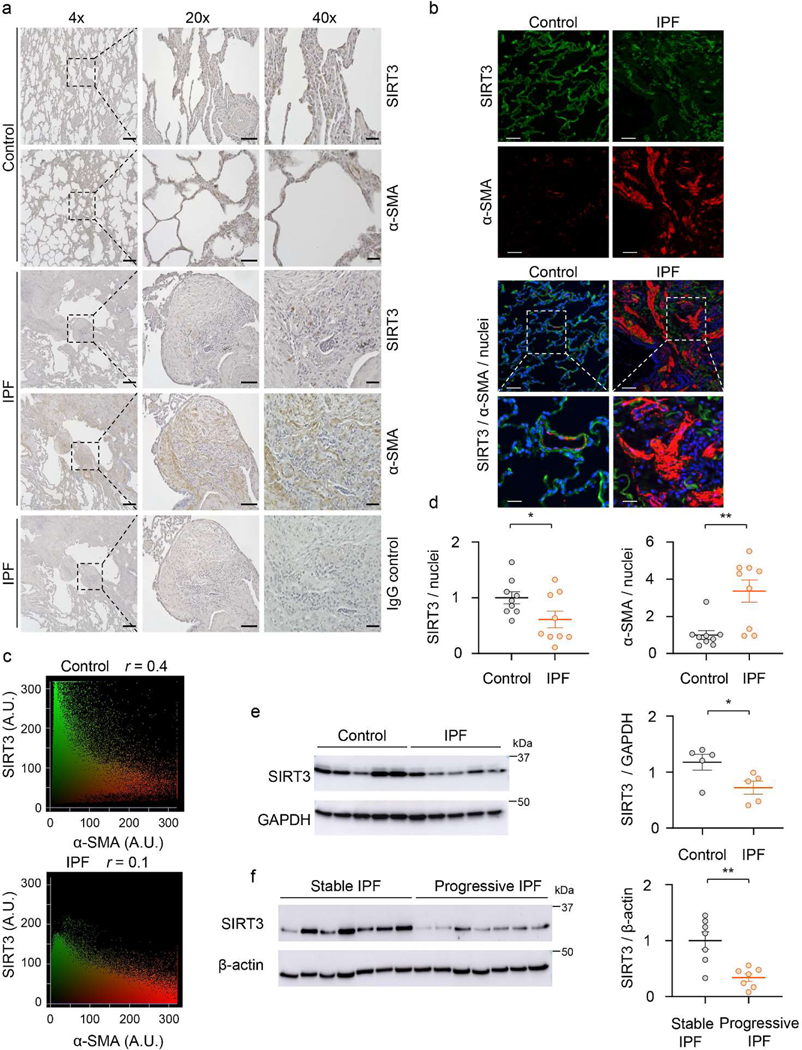

We first assessed the levels of the mitochondrial sirtuin, SIRT3, in the age-related lung disorder, IPF. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis showed significantly lower SIRT3 expression in the fibroblastic foci (FF) that are enriched in α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)-expressing myofibroblasts (Figure 1a). To confirm that myofibroblasts are relatively deficient in SIRT3, we performed immunofluorescence (IF) staining of normal subject (control) and IPF lung tissues; in markedly remodeled areas of IPF lung that express high levels of α-SMA, the expression of SIRT3 was almost absent (Figure 1b, top panel). A higher magnification shows that α-SMA is normally expressed in a small blood vessel that also expresses SIRT3; in contrast, IPF myofibroblasts do not show an appreciable expression of SIRT3 (Figure 1b, bottom panel). Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity and Pearson’s correlation (r) revealed a lower correlation of SIRT3 and α-SMA in IPF, in comparison to control (r = 0.1 vs. r = 0.4, respectively) (Figure 1c). Quantitative analysis of IF images from control and IPF lung tissues further supports a markedly reduced expression of SIRT3 in IPF, while α-SMA is significantly increased (Figure 1d). Next, we examined the SIRT3 protein expression in isolated fibroblasts from lung explants of IPF human subjects and control subjects. SIRT3 expression was found to be significantly downregulated in IPF fibroblasts, as compared to control fibroblasts (Figure 1e). A similar decrease in the expression of SIRT3 was observed in alveolar mesenchymal cells isolated from lungs of a cohort of IPF patients with progressive (defined as ≥ 10% decline in forced vital capacity over the preceding 6 months) and stable (defined as < 5% decline in forced vital capacity over the preceding 6 months) lung function (Figure 1f). The specificity of the SIRT3 antibody used in western blots was confirmed by both overexpression and silencing approaches (Extended figure 1), and the specificity of the same antibody for IHC and IF studies has been previously reported32. These data collectively indicate that SIRT3 expression is reduced in IPF, and that its deficiency may identify a subset with more progressive disease.

Figure 1: SIRT3 is decreased in IPF lungs.

(a) Representative images show SIRT3, α-SMA and control IgG immunostaining (DAB) of non-IPF control or IPF lung sections. Dashed lines indicate regions that are enlarged and displayed on the right side. Scale bar 4X images: 400 μm, 20X images: 100 μm, 40X images: 40 μm. (b) Patterns of SIRT3 and α-SMA immunofluorescence in lung sections from control and patients with IPF. Dashed boxes are magnified to display merged regions. SIRT3 -green; α-SMA -red; nuclei -blue. Sacle bar 50 μm. (c) Scattergrams indicate fluorescence intensity and Pearson’s correlation (r) for images depicted in (b). (d) Quantitative analysis of SIRT3/nuclei and α-SMA/nuclei fluorescence intensity ratios from lung sections of control and IPF subjects; n = 9 representing 3 independent subjects, each with analysis of 3 random fields. Data presented as means ± s.e.m; *P = 0.0482 (unpaired t-test, two-tailed); **P = 0.0020 (unpaired t-test, two-tailed). (e, f) Western blot and quantitative analysis of SIRT3 in (e) control and IPF fibroblasts (n = 5 per group), *P = 0.0368 (unpaired t-test, two-tailed); and (f) fibroblasts from stable and progressive IPF (n = 7 per group). Data presented as means ± s.e.m; **P = 0.0020 (unpaired t-test, two-tailed).

SIRT3 expression is downregulated with fibrogenic lung injury and its restitution during the repair phase restores capacity for fibrosis resolution.

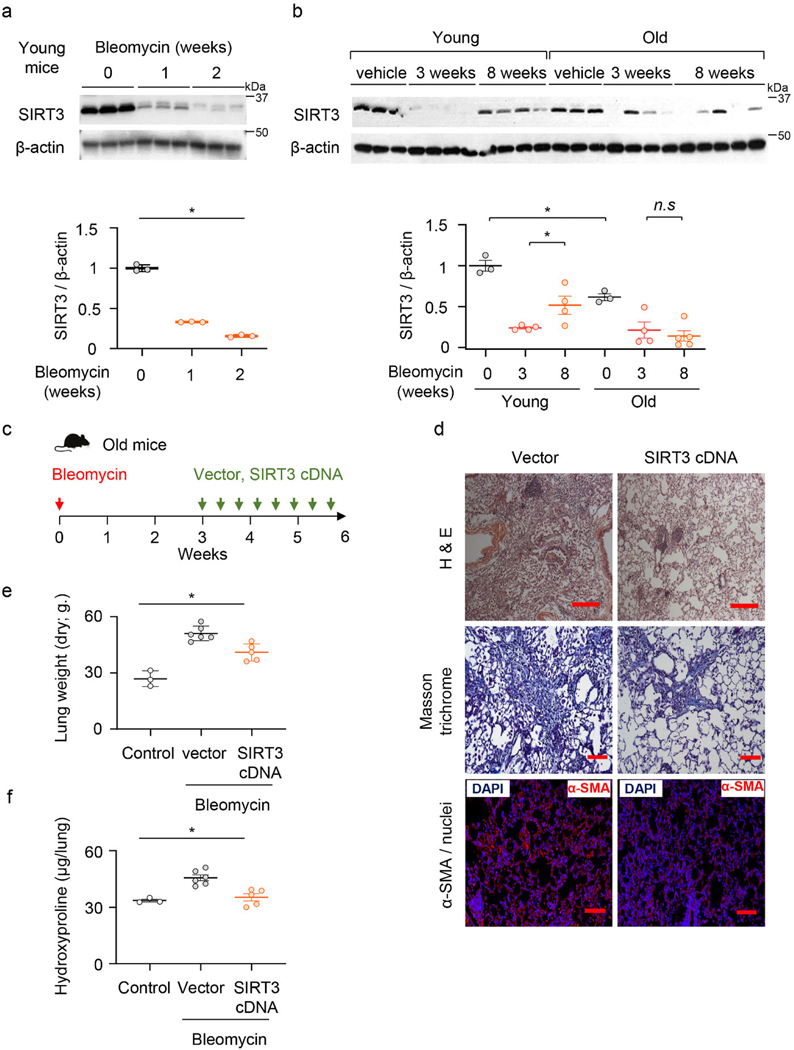

Based on our findings that SIRT3 is decreased in human IPF lung tissues, we examined levels of SIRT3 expression in lungs of mice subjected to fibrogenic injury. SIRT3 was down-regulated in a time-dependent manner, at day 7 and 14, in whole lung homogenates following intra-tracheal administration of fibrogenic chemotherapeutic agent, bleomycin (Figure 2a). Since young mice are known to resolve fibrosis at later time points33, we determined if the levels of SIRT3 recover during the late resolution phase. While SIRT3 levels are significantly upregulated at 8 weeks in comparison to the 3-week time-point in young mice, SIRT3 expression fails to recover at this delayed time-point in aged mice (Figure 2b). These data indicate that in aged mice that have diminished capacity for fibrosis resolution, levels of SIRT3 in the lung fail to recover.

Figure 2: SIRT3 is suppressed during the fibrogenic phase of lung injury, and its restitution resolves age associated persistent fibrosis.

(a) Representative western blot and quantitative analysis of SIRT3 in lung homogenates from young mice that received saline (control) or bleomycin for 1 or 2 weeks; n = 3 per group; Data presented as means ± s.e.m.; *P < 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA). (b) SIRT3 expression in lungs of young and old mice at baseline (n = 3 per group), at 3 weeks (n = 4 per group) and at 8 weeks (n = 4 in young and n = 5 in old). Data presented as means ± s.e.m.; *P < 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA), n.s. = not significant.. (c) Schematic of timing of SIRT3 cDNA plasmid or vector (control) administration in old mice that were subjected to bleomycin-induced lung injury. (d) Representative H&E, Masson’s trichrome blue and α-SMA-immunofluorescence images from lung sections of old mice; vector or SIRT3 cDNA plasmid were injected (i.t.) 2 weeks after bleomycin lung injury; α-SMA –red, nuclei -blue. H&E images (10X) Scale bar 200 μm; Masson’s trichrome images (20X) Scale bar 100 μm; Immunofluorescence images (20X) Scale bar 100 μm. (e, f) Lung dry weight (e) and whole lung hydroxyproline content (f) were analyzed from young and old uninjured mice (n = 3 per group) and bleomycin-injured mice treated with vector control (n = 6 per group) and SIRT3 cDNA (n = 5 per group). Data presented as means ± s.e.m; for (e) *P < 0.001, for (f) *P < 0.0006 (one-way ANOVA).

Next, we determined whether in vivo restitution of SIRT3 in aged mice facilitates resolution of age-associated lung fibrosis. Aged mice with bleomycin lung injury were treated with SIRT3 cDNA overexpressing or control (empty) plasmid by oropharyngeal delivery every other day from week 3 to 6 (Figure 2c; Extended figure 2a). We analyzed cellular expression of SIRT3 in both bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells and in FACS-sorted cells from whole lung collagenase digest. We analyzed expression of exogenously delivered cDNA based on presence of the HA-tag spanning the SIRT3 cDNA sequence. BAL cells of mice treated with SIRT3 cDNA plasmid had markedly increased expression of SIRT3 mRNA that was almost fully accounted for by delivery of exogenous SIRT3-HA cDNA (Extended figure 2b). This suggests that BAL cells are able to efficiently uptake/transcribe the SIRT3 cDNA plasmid by this route of delivery. To further confirm specific cell types that may preferentially uptake the plasmid, we FACS sorted whole lung collagenase digest of SIRT3 cDNA or control plasmid treated mice. As expected, we saw an increase in the recruitment of macrophages (CD45+/F4 80+/MerTK+) with bleomycin injury (Extended figure 2c, d). These sorted macrophages express markedly high levels of total SIRT3 and SIRT3-HA mRNA (Extended figure 2e); in contrast, whole lung digest sorted alveolar epithelial cells (CD45-/EpCAM+/CD31-) did not show a similar increase (Extended figure 2f). Adherence-purified fibroblasts expressed exogenously delivered SIRT3 cDNA, albeit at much lower levels in comparison to macrophages (Extended figure 2g). Thus, lung macrophages preferentially uptake/express exogenous airway delivery of SIRT3 cDNA. Histopathological analysis of lung at 6 weeks after lung injury and 3 weeks after SIRT3 cDNA treatment revealed significantly decreased fibrosis, as evidenced by histopathology, Masson’s trichrome staining for collagen, and reduced α-SMA-expressing myofibroblast accumulation in lungs (Figure 2d). These tissue remodeling effects were associated with significantly reduced dry lung weights (Figure 2e) and hydroxyproline content (Figure 2f) in treated mice. Thus, restoration of SIRT3 was effective in reversing established and persistent lung fibrosis in aged mice.

SIRT3 expression is downregulated during myofibroblast differentiation.

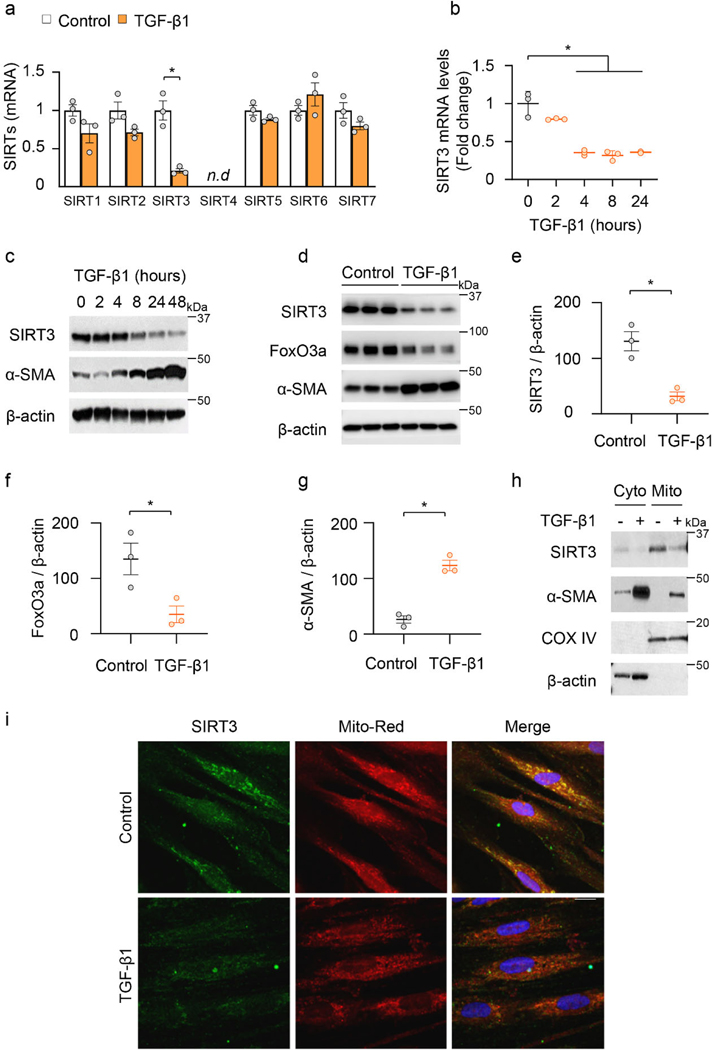

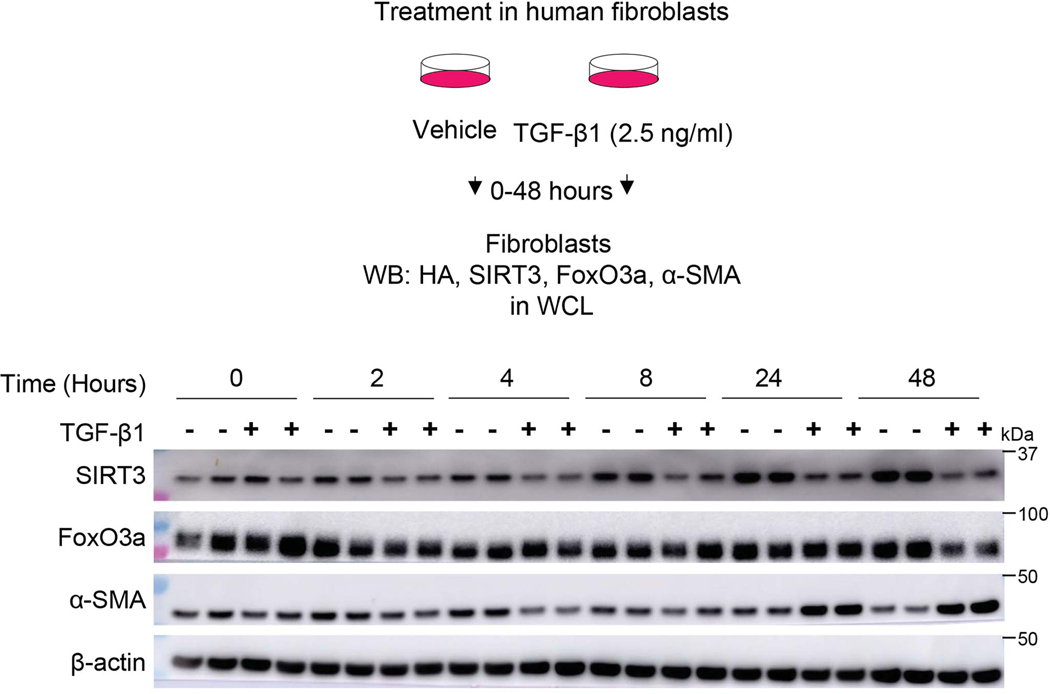

Since SIRT3 is downregulated in IPF lung tissues and in an in vivo murine model of lung fibrosis, we postulated that the pro-fibrotic cytokine, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), may contribute to the suppression of SIRT3. TGF-β1 markedly downregulated the mRNA expression of SIRT3, while not significantly affecting the expression of the other six mammalian sirtuins in human lung fibroblasts (IMR-90; Affymetrix U133A chip) (Figure 3a). This suppressive effect of TGF-β1 was confirmed at both the mRNA and protein levels and was found to occur in a time-dependent manner (Figure 3b; Extended figure 3). Furthermore, TGF-β1-induced downregulation of SIRT3 is accompanied by an upregulation of α-SMA, a marker of myofibroblast differentiation, and a relatively delayed downregulation of FoxO3a, a forkhead transcription factor that regulates oxidative stress and apoptotic responses (Figure 3c-g; Extended figure 3).

Figure 3: Mitochondrial SIRT3 is decreased in activated myofibroblasts.

(a) Sirtuin family gene expression patterns in human fibroblasts that were treated with or without TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) for 24 hours. n = 3 per group; Data presented as means ± s.e.m., *P = 0. 0035 (unpaired t-test, two-tailed); n.d. -not detected. (b) SIRT3 mRNA levels (fold change relative to control) in human fibroblasts treated with TGF-β1 for indicated time. n = 3 per group; Data presented as means ± s.e.m.; *P < 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA). (c) Representative western blots showing SIRT3 and α-SMA levels in human fibroblasts stimulated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml). (d-g) SIRT3, FoxO3a and α-SMA levels in human fibroblasts treated with TGF-β1 (0 or 2.5 ng/ml) for 48 hours. n = 3 per group; Data presented as means ± s.e.m.; for SIRT3 (e) *P = 0.0064 (unpaired t-test, two-tailed); FoxO3a (f) *P = 0.0011 (unpaired t-test, two-tailed); and α-SMA (g) *P = 0.0365 (unpaired t-test, two-tailed). (h) Protein levels of SIRT3, α-SMA and COX IV in cytoplasmic and mitochondrial fractions obtained from human fibroblasts stimulated with TGF-β1 (0 or 2.5 ng/ml) for 24 hours. (i) Immunofluorescence staining of SIRT3 and mitochondria in human lung fibroblasts treated with TGF-β1 (0 or 2.5 ng/ml) for 24 hours. SIRT3 -green; mitochondria -mitotracker red; nuclei -blue. Scale bar 10 μm.

SIRT3 is a known mitochondrial deacetylase19. Subcellular fractionation revealed that SIRT3 is enriched in the mitochondrial fraction and decreases upon TGF-β1 stimulation of human lung fibroblasts (Figure 3h). Similar findings were observed by immunofluorescence staining which showed co-localization of the mitochondrial marker, Mito-Red, with SIRT3 in unstimulated cells and a marked downregulation of SIRT3 in this subcellular compartment with TGF-β1 treatment (Figure 3i). Together, these data suggest that the mitochondrial sirtuin, SIRT3, is selectively downregulated during the process of myofibroblast differentiation.

The anti-fibrotic effect of SIRT3 overexpression is associated with induced susceptibility to myofibroblast apoptosis.

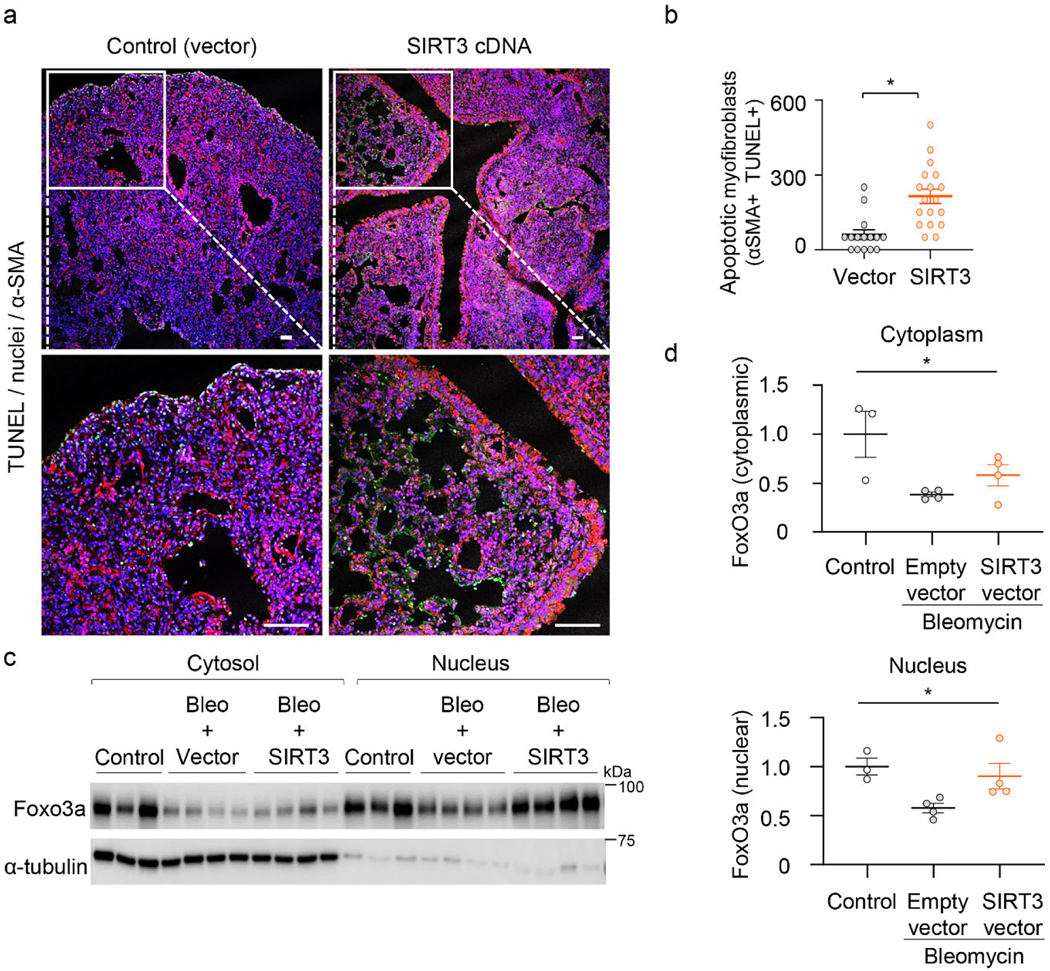

Apoptosis of myofibroblasts is a hallmark of fibrosis resolution34. To determine whether the anti-fibrotic effects of SIRT3 restitution in aged mice is associated with recovery of apoptosis susceptibility in myofibroblasts, we performed terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL; green) and co-staining for α-SMA (a marker of myofibroblasts; red) on lung sections of SIRT3 or control plasmid treated mice. A higher number of apoptotic myofibroblasts was observed in lungs of mice treated with SIRT3 cDNA (Figure 4a, b).

Figure 4: SIRT3 in vivo overexpression sensitizes myofibroblasts to undergo apoptosis.

(a) Immunofluorescence staining of murine lung tissues showing apoptotic cells by TUNEL staining (green) six weeks following bleomycin injury; α-SMA –red; DAPI –blue. Dashed lines indicate regions selected for higher magnification images in the bottom panels. Scale bar 50 μm. (b) Quantitative analysis of apoptotic cells from randomly selected regions of images in mice in control (vector) and SIRT3-treated mice. 3 mice per group; Data presented as means ± s.e.m., *P = 0.0002 (unpaired t-test, two-tailed). (c, d) Western blot and quantitative analysis of FoxO3a in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of lung fibroblasts isolated from aged mice without injury (n = 3) or subjected to bleomycin followed by treatment with empty vector or SIRT3 cDNA (n = 4 in each treated group). Data presented as means ± s.e.m.; *P = 0.0306 (one-way ANOVA, comparing groups indicated in d); *P = 0.0357 (one-way ANOVA, comparing groups indicated in e).

Since FoxO3a, along with SIRT3, was also downregulated during TGF-β1 induced myofibroblast differentiation (Figure 3d), we assessed whether in vivo SIRT3 restitution leads to recovery of FoxO3a expression. SIRT3 mediated deacetylation of FoxO3a mediates its translocation to the nucleus and transcriptional activation25,35. Analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of lung fibroblasts of mice treated with the SIRT3 cDNA plasmid showed significantly enhanced presence of FoxO3a in the nuclear fraction, supporting cytoplasmic-to-nuclear shuttling of FoxO3a (Figure 4c, d).

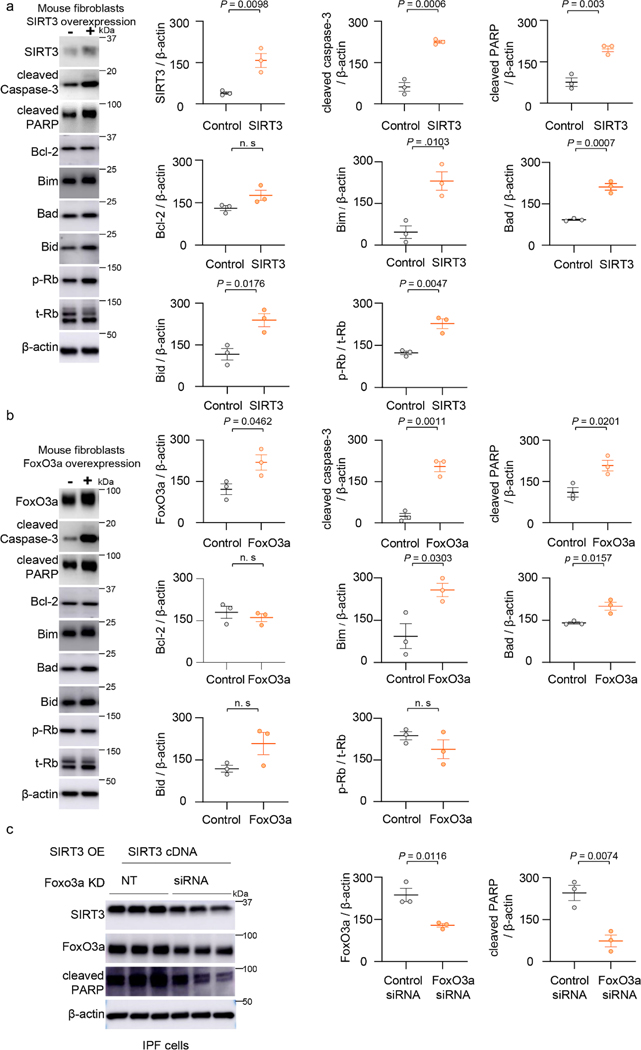

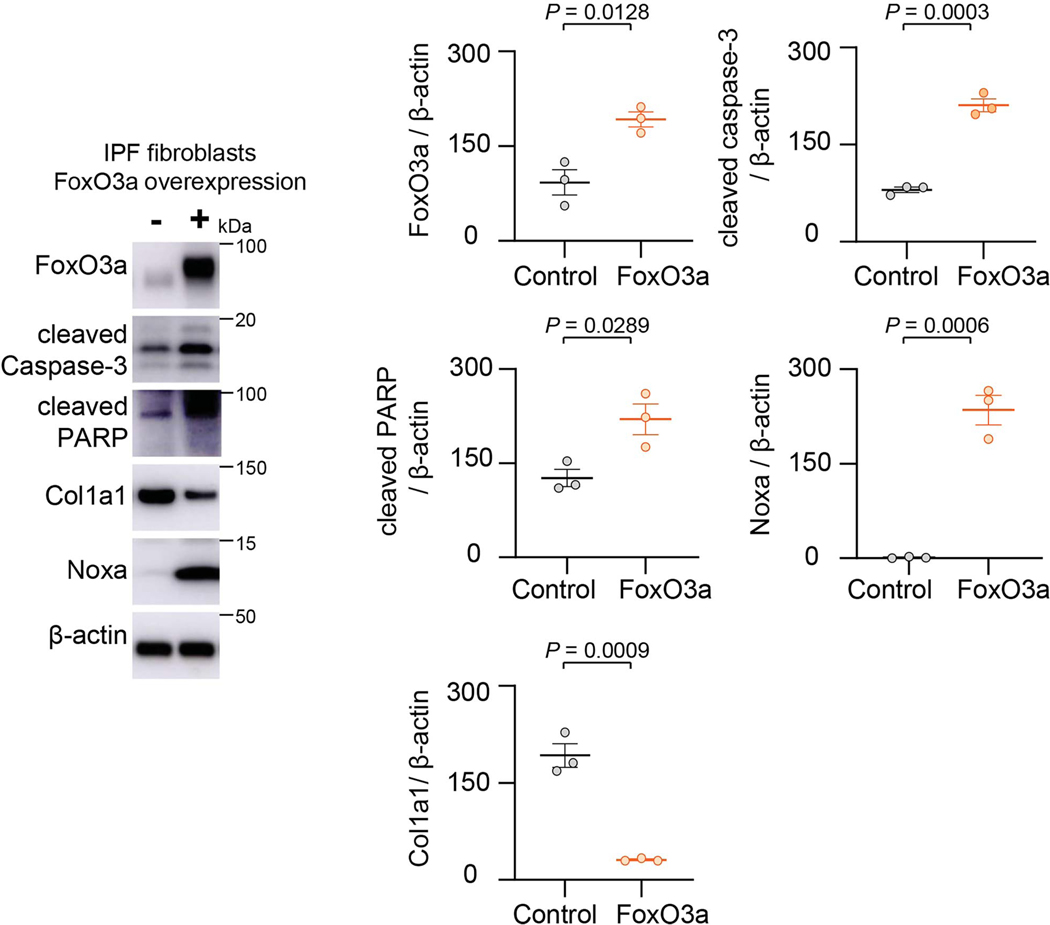

To determine if the SIRT3-FoxO3a axis regulates fibroblast apoptosis, we independently overexpressed each of these factors in isolated murine lung fibroblasts and assessed apoptosis susceptibility. Overexpression of SIRT3 in fibroblasts demonstrated higher propensity to apoptosis, as evidenced by increased expression of activated caspase-3 and cleaved PARP; this effect was associated with the upregulation of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, Bim, Bad and Bid, while expression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein was unchanged (Figure 5a). Similarly, overexpression of the FoxO3a transcription factor induced fibroblast apoptosis, without affecting Bcl-2 expression but inducing expression of Bim and Bad; however, unlike SIRT3 overexpression, Bid levels did not show a statistically significant induction with FoxO3a overexpression (Figure 5b). In IPF lung fibroblasts, FoxO3a overexpression induced apoptosis, while inducing Noxa and inhibiting Col1a1 (Extended figure 4). These data suggest that SIRT3, both in vivo and in vitro, modulates apoptosis susceptibility of lung fibroblasts, and suggest a potential role of FoxO3a in mediating the effects of SIRT3. To more directly determine the requirement for FoxO3a in mediating SIRT3-induced apoptosis, we silenced FoxO3a in human IPF fibrotic fibroblasts prior to overexpression of SIRT3. FoxO3a silencing reduced apoptosis, as evidenced by lower levels of cleaved PARP (Figure 5c), indicating that SIRT3-mediated apoptosis is, at least partly, dependent on FoxO3a induction/activity.

Figure 5: SIRT3 or FoxO3a overexpression promotes apoptosis in murine fibroblasts.

2222(a) Mouse lung fibroblasts were transfected with control or SIRT3 cDNA plasmid for 48 hours and whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting for SIRT3, cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP, Bcl-2, Bim, Bad, Bid, phospho-Rb and total-Rb. n = 3 per group; Data presented as means ± s.e.m., *P values as indicated by unpaired t-test, two-tailed statistical analysis. (b) FoxO3a, cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP, Bcl-2, Bim, Bad, Bid, phospho-Rb and total-Rb protein levels by western blot analyses in control plasmid or FoxO3a overexpressing mouse fibroblasts. n = 3 per group; Data presented as means ± s.e.m., P values as indicated by unpaired t-test, two-tailed statistical analysis. (c) IPF fibroblasts were transfected with non-targeting or FoxO3a specific siRNA prior to SIRT3 overexpression; western blot analyses and quantitation of expression levels of FoxO3a and cleaved PARP are shown. n = 3 per group; Data presented as means ± s.e.m., P values as indicated by unpaired t-test, two-tailed statistical analysis.

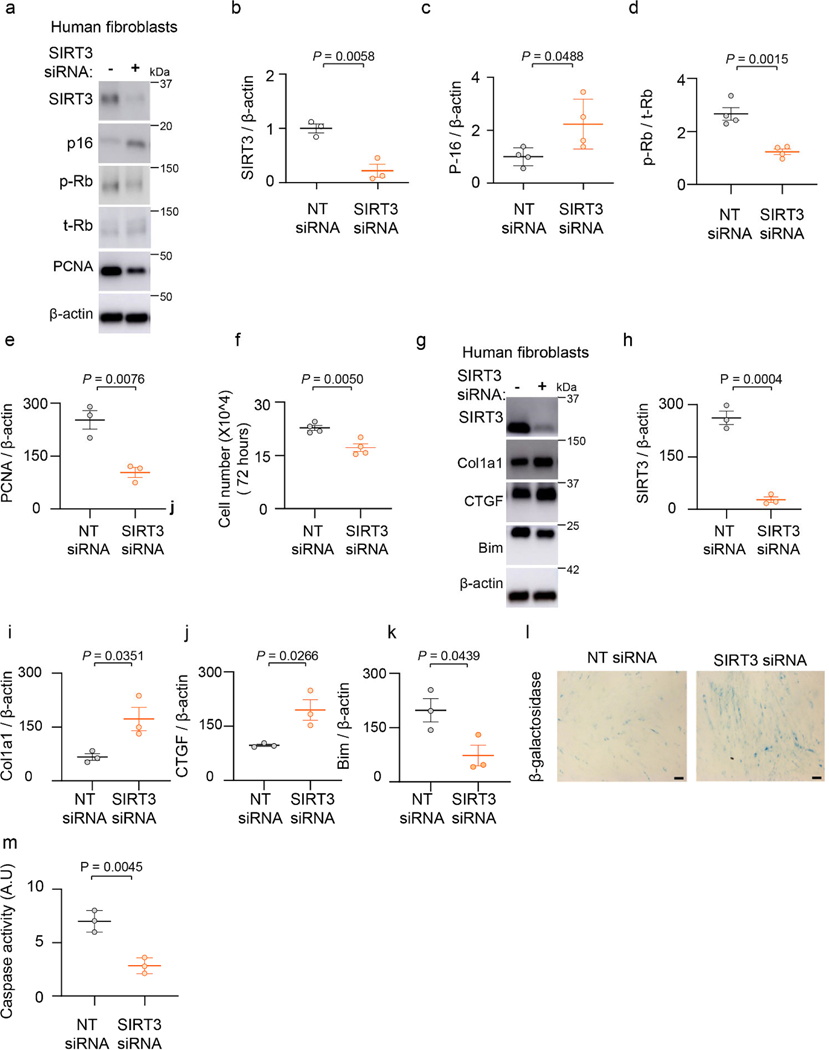

SIRT3 silencing mediates senescence, apoptosis resistance and induces pro-fibrotic genes in human lung fibroblasts.

Previous studies have linked senescence to apoptosis resistance33; we explored whether SIRT3 deficiency is sufficient to induce both senescence and apoptosis resistance of lung fibroblasts. We depleted SIRT3 in human lung fibroblasts by RNAi and assessed markers of senescence and apoptosis (Figure 6a). SIRT3 silencing induced expression of p16, while downregulating phospho-Rb and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (Figures 6a-e) and cell numbers were concomitantly reduced at 72 hours (Figure 6f), supporting cell cycle arrest typical of cellular senescence. The pro-fibrotic markers, Col1a1 and CTGF, were markedly upregulated in SIRT3-silenced fibroblasts (Figure 6g-j), while the pro-apoptotic protein, Bim, was down-regulated (Figure 6g, k). Staining for SA-β-gal confirmed induction of senescence in SIRT3 silenced fibroblasts (Figure 6l). Fibroblasts in which SIRT3 was suppressed exhibited decreased susceptibility to staurosporine-induced apoptosis as compared to control fibroblasts (Figure 6m). Together, these data indicate that depletion of SIRT3 leads to a pro-senescent, anti-apoptotic, and pro-fibrotic phenotype of fibroblasts.

Figure 6: SIRT3 deficiency induces fibroblast senescence and resistance to apoptosis and upregulates pro-fibrotic markers.

(a) Human lung fibroblasts (IMR-90) were treated with non-targeting or SIRT3 siRNA, and analyzed by western blot analysis for SIRT3, p16, phospho-Rb, total-Rb and PCNA levels. (b-e) Quantitative analysis of SIRT3 (n = 3), p16 (n = 4), phospho-Rb/total-Rb (n = 4) and PCNA (n = 3) from (a). Data presented as means ± s.e.m., P values as indicated by unpaired t-test, two-tailed statistical analysis. (f) Analysis of cell numbers in human fibroblasts after 96-hour treatment with non-targeting or SIRT3 siRNA. n = 4 per group; Data presented as means ± s.e.m., P values as indicated by unpaired t-test, two-tailed statistical analysis. (g) Western blot analyses of expression levels of SIRT3, Col1a1, CTGF and Bim in human fibroblasts after treatment with non-targeting or SIRT3 siRNA. (h-k) Quantitative analysis of SIRT3, Col1a1, CTGF and Bim levels from experiment described in (g). n = 3 per group; Data presented as means ± s.e.m., P values as indicated by unpaired t-test, two-tailed statistical analysis. (l, m) IMR-90 fibroblasts transfected for 48 hours with non-targeting or SIRT3 specific siRNA were analyzed for β-galactosidase staining (Scale bar 50 μm) (l) and for caspase-3 activity (m). n = 3 per group; Data presented as means ± s.e.m., P values as indicated by unpaired t-test, two-tailed statistical analysis.

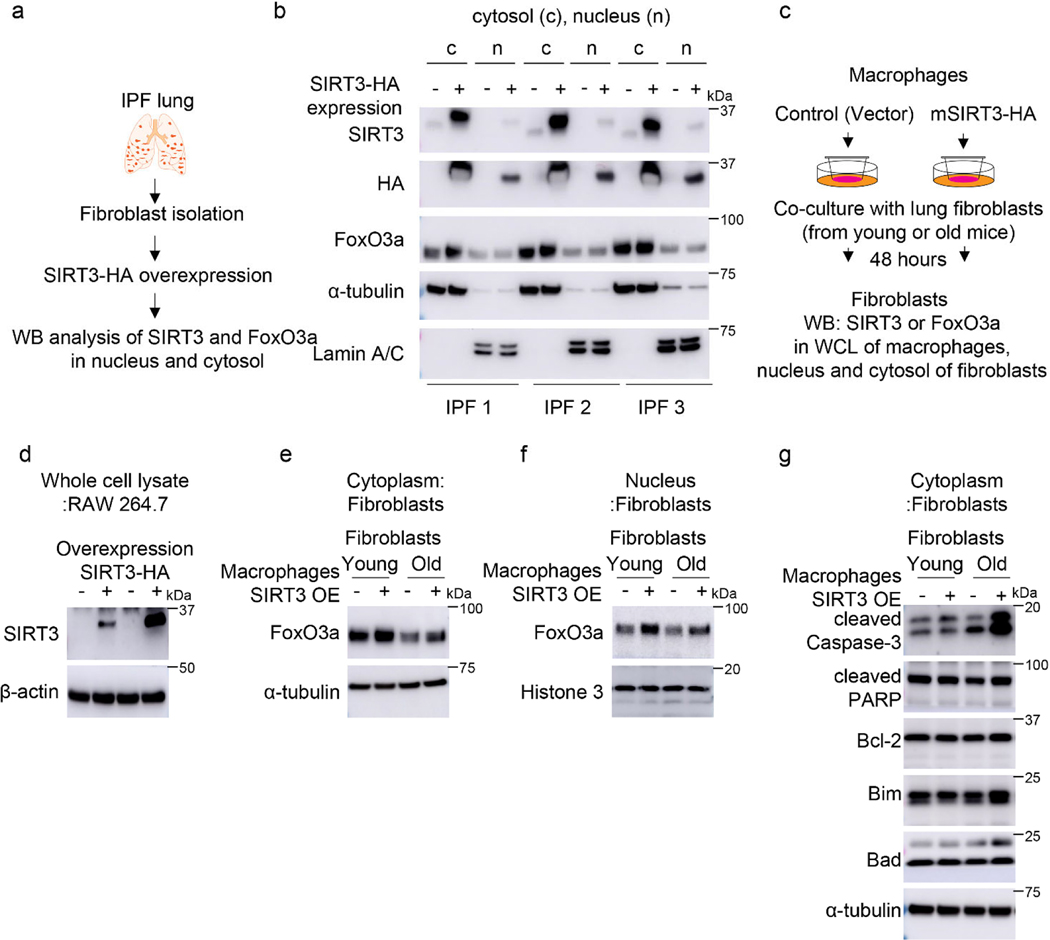

Macrophage SIRT3 induces Foxo3a activation in fibroblasts via a paracrine mechanism.

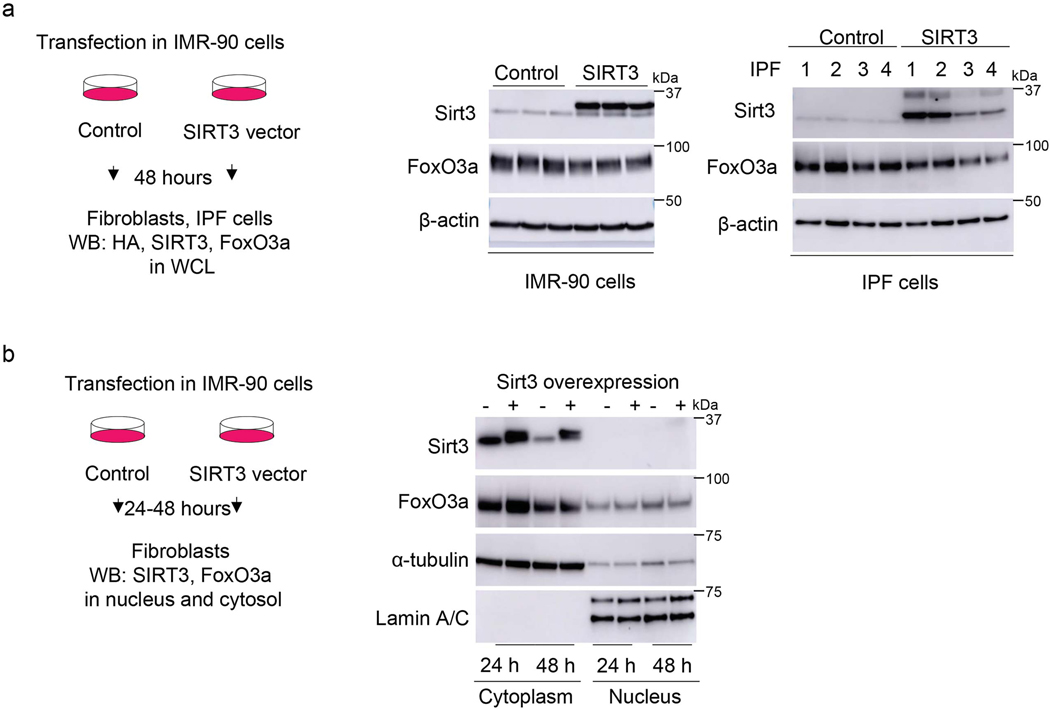

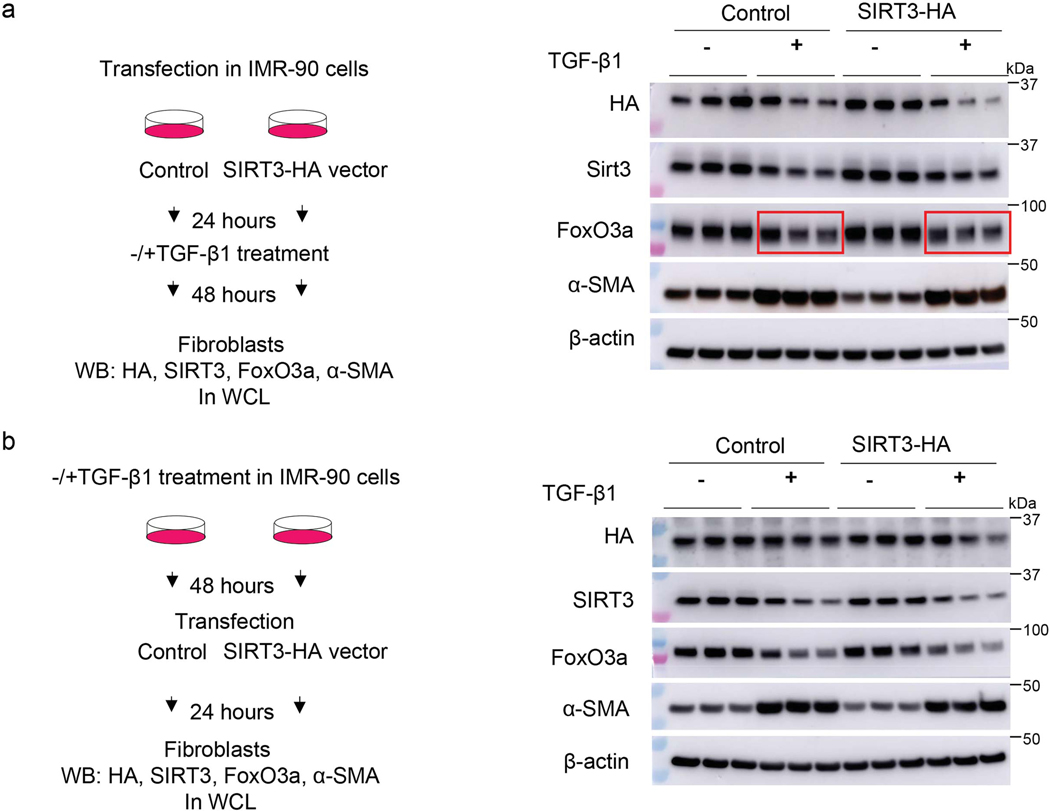

To gain additional mechanistic insights into the relationship between SIRT3 and FoxO3a, SIRT3 was overexpressed in normal and fibrotic lung fibroblasts and FoxO3a levels/localization were analyzed. Contrary to our expectations, overexpression of SIRT3 cDNA in IMR-90 or IPF fibroblasts neither enhanced total FoxO3a levels (Extended figure 5a) nor facilitated nuclear translocation (Extended figure 5b; Figure 7a, b). Next, we overexpressed SIRT3 in TGF-β1 treated cells to determine if this would result in recovery of FoxO3a levels downregulated by TGF-β1. However, overexpression of SIRT3 in human lung fibroblasts followed by TGF-β1 stimulation did not significantly alter levels of FoxO3a expression (Extended figure 6). These data suggested that the observed effects of SIRT3 overexpression on lung fibroblast activation of FoxO3a in vivo may occur through a non-autonomous mechanism involving cell-cell interactions.

Figure 7: SIRT3 overexpression in macrophages activates FoxO3a in fibroblasts via paracrine signaling mechanism.

(a) Experimental design of studies of SIRT3-HA overexpression in IPF fibroblasts. (b) Representative western blots showing SIRT3, HA and FoxO3a levels in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of IPF fibroblasts (n = 3 different IPF subjects) overexpressing control or SIRT3-HA plasmid; c -cytoplasm, n -nuclear fraction. (c) Design of co-culture studies of SIRT3-HA overexpressing RAW264.7 macrophages and lung fibroblasts from young or old mice; WCE -whole cell lysates. (d-f) Western blots showing SIRT3 levels in whole cell lysates of RAW264.7 (d) or FoxO3a levels in the cytoplasm (e), or FoxO3a levels in nuclear fractions (f) from young and old mouse fibroblasts. (g) Western blots showing expression levels of cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP, Bcl-2, Bim and Bad in cytoplasmic fractions from young and old mouse fibroblasts in co-culture with RAW264.7 mouse macrophages, as depicted in (c). Co-culture experiments were performed twice with each lane of the western blots representing pooled wells from each 6-well plate.

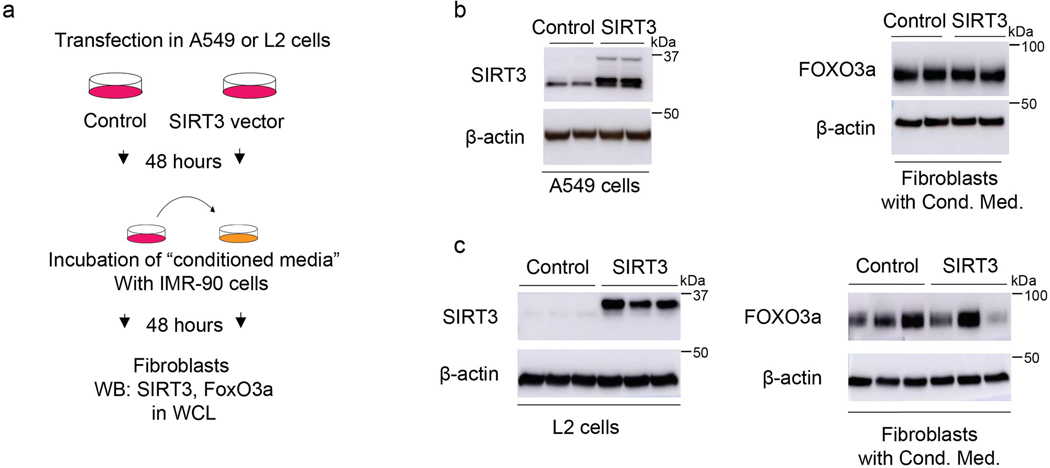

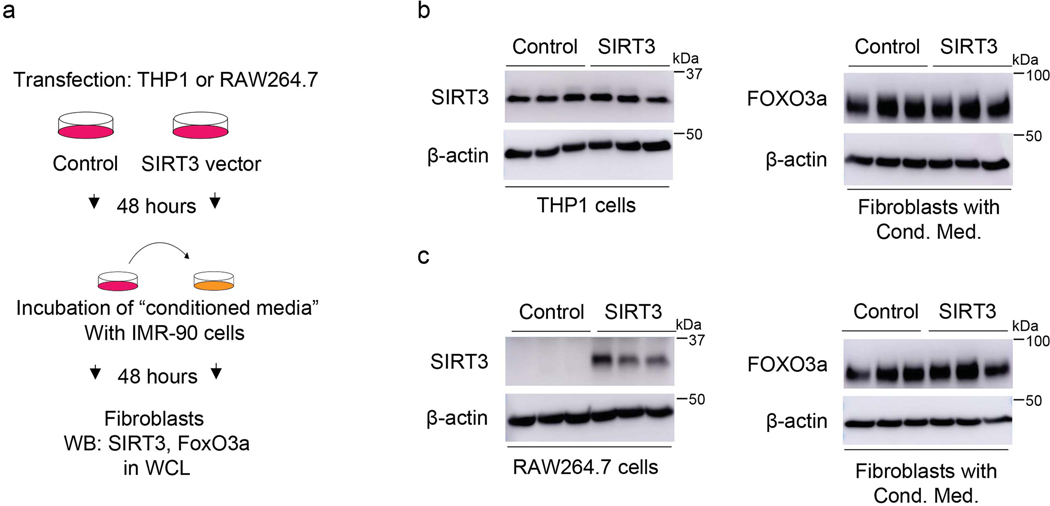

Next, we explored whether epithelial-fibroblast crosstalk may account for fibroblast FoxO3a activation in response to SIRT3 cDNA treatment. Using two different epithelial cell lines (human alveolar epithelial cell line, A549; and murine alveolar epithelial cell line, L2), we overexpressed SIRT3 cDNA, collected the conditioned media and transferred onto IMR-90 fibroblasts; this did not result in FoxO3a induction/stabilization (Extended figure 7). Conditioned media transfer studies using SIRT3 overexpression in two different macrophage cell lines (human macrophages cell line, THP1; mouse peritoneal macrophages, RAW264.7) showed similar results (Extended figure 8).

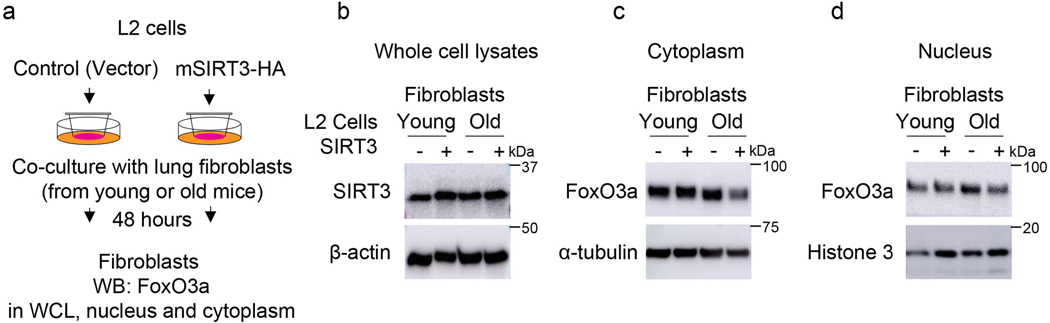

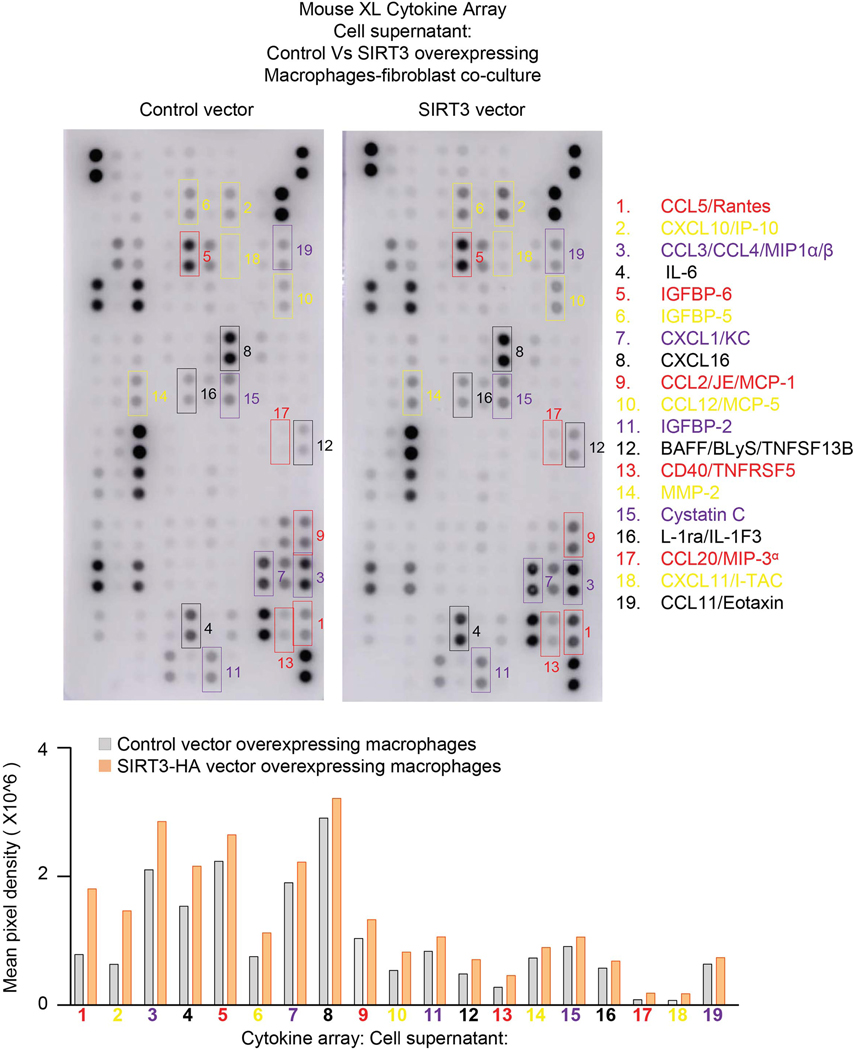

To more closely simulate the paracrine effects of cell-cell communication in vivo, we utilized a Transwell co-culture system in which continuous release of and stimulation by paracrine mediators may occur (Figure 7c). SIRT3 overexpressing L2 epithelial cells failed to induce FoxO3a nuclear translation in co-cultured fibroblasts (Extended figure 9). However, SIRT3 overexpression in RAW264.7 macrophages revealed enhanced levels of FoxO3a in nuclear fraction of fibroblasts (Figure 7d-f), supporting FoxO3a activation by a paracrine mediator released by macrophages. Since we observed an induction of pro-apoptotic markers of the Bcl-2 family and execution of apoptosis in murine lung fibroblasts overexpressing FoxO3a (Figure 5a, b), we tested whether these same pro-apoptotic effects are preserved in this macrophage-fibroblast co-culture system. In concert with FoxO3a activation/nuclear translocation, the pro-apoptotic proteins, Bim and Bad, along with increased apoptosis were induced in fibroblasts co-cultured with SIRT3-overexpressing macrophages (Figure 7g). Although the specific mediator(s) that augment FoxO3a in fibroblasts are currently unknown, a number of potential candidates were identified by a cytokine array (Extended figure 10). Together with the finding that macrophages are the primary cells that uptake airway delivery of SIRT3 cDNA, these data support the concept that the observed therapeutic effect of SIRT3 requires macrophage-fibroblast crosstalk via activation of a SIRT3-FoxO3a signaling axis that facilitates fibrosis resolution/reversal (Figure 7h).

DISCUSSION

Aging is associated with diminished regenerative capacity and clinical syndromes of persistent or progressive fibrosis that affects diverse organ systems36,37. Animal models have traditionally failed to recapitulate this critical aspect of disease progression and have largely focused on the development of fibrosis. It is biologically plausible that the recalcitrant nature of these non-resolving fibrotic disorders may be related to the inability to “turn off” a physiological repair response, in contrast to a heightened fibrotic response to the initial tissue injury. Our group has previously demonstrated that the non-resolving nature of fibrotic syndromes can, at least partially, be recapitulated by studying injury-repair responses in aged mice33. In this study, we investigated a new role of the anti-aging mitochondrial sirtuin, SIRT3, in promoting resolution of lung fibrosis employing an aging mouse model. We observed marked reduction of SIRT3 expression in lungs of human subjects with IPF, which was further reduced in patients with rapid progression. This finding was recapitulated in the animal model of aged mice that failed to recover SIRT3 levels during the resolution phase of lung injury, in contrast to gradual recovery in young mice with inherent resolution capacity. Exogenous restitution of SIRT3 levels in aged mice restored capacity for fibrosis resolution in association with induced FoxO3a activation in myofibroblasts that recover susceptibility to apoptosis. In ex-vivo studies, the pro-fibrotic cytokine TGF-β1, at least partially, accounted for the loss of SIRT3-FoxO3a signaling axis in fibroblasts; however, reconstitution of SIRT3 in these cells failed to fully account for FoxO3 activation in a cell autonomous manner. Interestingly, over-expression of SIRT3 in macrophages was able to more efficiently induce FoxO3a activation in co-cultured fibroblasts, supporting an additional cell non-autonomous mechanism for modulating fibroblast behavior. Together, these studies implicate a critical role for SIRT3 in modulating cellular plasticity and tissue regenerative capacity that involves macrophage-fibroblast crosstalk.

These studies are the first, to our knowledge, to demonstrate a role for SIRT3 in the resolution of persistent lung fibrosis associated with aging. While several reports have demonstrated putative anti-fibrotic roles for SIRT3 in multiple organs systems, including the lung, these studies primarily evaluated effects on the initiation/development of fibrosis29,30,35,38,39. Our studies clearly demonstrate that restitution of SIRT3 in vivo in aged mice during the late reparative phase was sufficient to reverse the persistent fibrotic phenotype. The potential for clinical translation is bolstered by the finding that SIRT3 is downregulated in alveolar mesenchymal cells of a subgroup of human subjects with rapidly progressing IPF. Although the number of human subjects studied here are relatively small, these proof-of-concept studies demonstrating benefits of SIRT3 restitution in an animal model of non-resolving lung fibrosis should motivate future therapeutic strategies to activate this pro-regenerative, anti-fibrotic pathway in age-related, progressive fibrotic diseases.

The mechanisms of how SIRT3 mediates its anti-fibrotic effects appears to be related, at least partly, to the induction/activation of FoxO3a in fibroblasts. FoxO3a, is a pro-longevity gene and transcription factor that regulates the expression of genes involved in cellular proliferation, metabolism, differentiation and apoptosis26,40. SIRT3 deacetylates FoxO3a at specific lysine residues, which facilitates migration of deacetylated (activated) FoxO3a to the nucleus25,35. SIRT3 has been reported to block cardiac hypertrophic response by augmenting FoxO3a mediated anti-oxidant defenses in mice35. We have proposed that apoptotic clearance of (myo)fibroblasts is essential to the resolution of fibrosis33,34,37,41, which may be accomplished by reinstating redox imbalance in these cells33. Our current studies revealed that exogenous induction of both SIRT3 and FoxO3a was sufficient to robustly induce apoptosis in lung (myo)fibroblasts, in association with induction of pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, while the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein was unchanged. These results are consistent with a critical role for Bcl-2 family proteins in controlling the apoptosis-resistant phenotype of myofibroblasts in refractory fibrotic disorders34,41–43. Our data support a role for SIRT3-FoxO3a signaling as a critical regulator of apoptosis susceptibility ex vivo and fibrosis resolution in vivo. However, it must be acknowledged that the complexity of signaling mechanisms regulating FoxO3a nuclear transfer that may not necessarily involve SIRT3-dependent deacetylation.

Similar to other studies that have shown downregulation or deactivation (nuclear exclusion) of FoxO3a in fibroblasts by TGF-β127,28,44, we found that this canonical pro-fibrotic cytokine concordantly decreases both FoxO3a and SIRT3 in stimulated fibroblasts. However, contrary to our expectation, we were unable to recover FoxO3a induction/activity by overexpression of SIRT3, both in constitutive (IPF fibroblasts) and TGF-β1 induced downregulation of SIRT3. This suggested the possibility that the observed in vivo effects of FoxO3a, specifically in fibroblasts, by airway gene delivery of Sirt3 may be mediated by an indirect effect on other lung cells. After testing multiple cellular models of alveolar epithelial cells and macrophages, we concluded that paracrine effects were most likely mediated by alveolar macrophages. In our ex vivo co-culture model, we detected a FoxO3a-inducing effect of macrophages over-expressing the Sirt3 gene. Furthermore, our in vivo studies indicate that macrophages preferentially uptake/express exogenously delivered SIRT3 cDNA. Thus, in addition to cell autonomous effects of SIRT3-FoxO3a signaling axis in fibroblasts, our data support the concept that pro-resolution effects of Sirt3 gene delivery is mediated by macrophage-fibroblast crosstalk.

Macrophages mediate pleiotropic effects during tissue injury repair processes45,46. Recent studies indicate an important role of macrophages in promoting resolution47–49, although mechanisms are incompletely understood. Our studies support the possibility that SIRT3 may function as a critical switch in determining the pro-fibrotic vs. pro-resolution phenotype of macrophages. This age-related macrophage dysfunction may be critical not only in conferring increased susceptibility to fibrosis from noninfectious injury, but also to defective innate immunity and repair responses to infectious agents such as the novel coronaviruses that adversely affect the elderly population50. Together, our studies support a critical role for SIRT3 and FoxO3a in age-related stress responses and in cell-cell communication to orchestrate a pro-regenerative response to tissue injury. Therapeutic strategies to restore these integrated longevity pathways to potentially reverse organ fibrosis deserve further study.

METHODS

Reagents

Porcine platelet-derived TGF-β1 was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Control vector and SIRT3 over-expressing mouse and human specific vectors were purchased from Sino Biological Inc. Sources, use and dilutions of antibodies used for the study are provided in Supplementary table 1. All kits used in this study have been listed in Supplementary table 2.

Human lungs

The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee under the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board. Lung sections of either healthy or IPF biopsies were provided by Airway Tissue Procurement Program Facility at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, and the Pulmonary Hypertension Breakthrough Initiative. Lung sections were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded before being cut into 5 μm slices, as previously described 31.

Lung histology and immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as described previously33. Images were acquired using a Nikon A1 Laser Confocal Microscope at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) High Resolution Imaging Facility. The levels of fluorescence were quantified and displayed as 2-dimensional scattergrams using Hamamatsu software (Hamamatsu Corporation). We also processed paraffin-embedded tissue sections for lung histology and immunohistochemical staining, including H&E, Masson’s trichrome or α-SMA staining as previously described 51.

Murine model of bleomycin lung injury and gene transfer

Aged (18–22 months) male C57BL/6 mice (National Institute on Aging) were used for in vivo studies. Mice were subjected to bleomycin treatment as described previously 51. For in vivo SIRT3 induction, total of 70 μl mixture of TurboFect™ transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 20 μg of SIRT3 or control vector was administered to mice via oropharyngeal route every alternate day. All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Bronchoalveolar lavage

Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and bled via transection of the abdominal aorta before perfusion of lungs with 3 ml of ice-cold PBS injected through the right ventricle. The trachea was then cannulated with a blunt 22-gauge needle and tied in place. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed with PBS. Aliquots of 0.5 to 1 ml were instilled into the lungs under direct observation to ensure that all segments of lung were inflated and aspirated back into the syringe. This was repeated two times per mouse.

FACS sorting

Lungs of bleomycin and control or SIRT3 vector treated mice were perfused with chilled PBS. Lung were chopped into small pieces and digested with collagenase (1 mg/ml) for 30 min/37 °C. Later, cells were passed through a sieve (70 μM). RBCs were lysed with ACK lysis buffer. Cells were counted by trypan blue dye-exclusion method. Lung cells were washed with PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA and incubated with anti-CD16/32 at dilution of 1:100 in PBS/0.5% BSA at 4°C for 10 minutes. After washing, cells were incubated with fluorochrome tagged antibodies at 4°C for 30 minutes. Antibodies Panel: anti CD45-V500, anti-CD31-FITC, anti-F480-APC, anti-MerTK-PE, anti-EPCAM-APC eflour 780. All cells were subsequently washed with PBS/0.5% BSA and resuspended in 1x PBS. Cells were sorted in 200μl media, washed with PBs and used for RNA isolation.

Cell culture

Primary lung fibroblasts were isolated and cultured from lung explants of human subjects undergoing lung transplantation with IPF or failed donors (controls), as previously described 51. All studies were approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA. Human fetal lung fibroblasts [Institute of Medical Research (IMR)-90] cells were purchased from Coriell Cell Repositories (Camden, NJ, USA). All cells were cultured as described earlier 52. Primary fibroblasts were isolated from the lungs of aged or young C57BL/6 mice +/− bleomycin treatment, as previously described 33.

Western blotting

Cell lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer and Lysates were quantitated using a Micro BCA™ Protein assay kit (Pierce) according to instructions. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and western immunoblotting was performed as previously described33. Densitometric analyses were performed using ImageJ software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Real-Time PCR

Total RNA from cells was isolated using the RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), and reverse transcribed to cDNA using Bio-Rad iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (catalog no.1708890; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR procedure and analysis was performed as described previously 33.

RNA interference

Fibroblasts were transfected with 50–100 nM targeting or non-targeting siRNA using Lipofectamine-RNaiMAX® in Opti-MEM™ medium (both from Life Technologies™), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells (2.5 × 105 /well) in 6-well plates were incubated in Opti-MEM™ medium containing specific or scrambled siRNA (0.1 μM) for 72 hours. After incubation with siRNA, the cell culture medium was changed to antibiotic free DMEM medium supplemented and treated as described in figure legends. The sense sequences used for siRNA are as follows: SIRT3: AAU CAG CUC AGC UAC AUC CUG CAG G; FoxO3a: UAG UGU GAC ACG GAA GAG AAG GUG G.

Hydroxyproline assay

Lung tissues were dried in an oven at 70°C for 48 h, and then hydrolyzed in 6N HCl at 95°C for 48 h. Hydroxyproline assay was performed using Hydroxyproline Assay Kit according to manufacturer instructions (QuickZyme® Biosciences) using hydroxyproline as a standard.

TUNEL assay

For TUNEL assay, cells were cultured followed by inclusion of paraformaldehyde and then 5′-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) assay using In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche). Nuclei were stained with DAPI and images were acquired using a Leica epifluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems).

In vitro overexpression of SIRT3 and FoxO3a

Cells were grown to 70% confluency and 1–2 micrograms of plasmid were transfected per well of 6 well plate using FuGENE®6 Transfection Reagent (Catalogue Number:E2693 ) from Promega Corporation, as per manufacturer’s instructions. Macrophages were transfected using Effectene® transfection reagent from Qiagen, as per the manufacturer’s instructions. For SIRT3 overexpression, control (pCMV-3-C-HA, Sino biological Inc. Cat# CV013) or SIRT3-HA carrying plasmid (pCMV-3-C-mSIRT3-HA, Sino biological Inc. Cat# MG50478-Cy or pCMV-3-C-hSIRT3-HA, Sino biological Inc. Cat# HG13033-Cy) were used. hFoxO3a expressing plasmid was purchased from Addgene Inc. HA-FoxO3a-WT Cat# 1787) was used for FoxO3a related overexpression studies.

TGF-β1 treatment of human fibroblasts

At approximately 70% confluency, fibroblasts were serum starved for 24 hours, followed by treatment with 2.5 ng/ml of TGF-β1 in serum free media for indicated timepoints.

Real-time PCR and transcriptome studies

Total RNA was isolated from lung tissues using the RNeasy® Mini kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed using iScript™ Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT-quantitative PCR (Bio-Rad). Real-time PCRs were performed using SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies™) and gene-specific primer pairs for Sirt3 and 18S rRNA. Primer sequences used in this study have been provided in Supplementary table 3. Real-time PCR and analysis were performed as described previously 52. Transcriptome studies (Affymetrix U133A chip) on TGF-β1 treated IMR-90 cells were processed and analyzed at Sequencing and Proteomics core facility at University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Isolation of mitochondria and nuclear/cytoplasmic fractions

Cellular mitochondria were isolated according to standard procedures, as described previously 52. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were isolated with NE-PER™ Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit available from Thermo Scientific (Catalogue Number:78833).

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analyses were performed using one-or two-tailed unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA to evaluate differences between groups. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 8.4.2), and precise P-values are provided. Values of n are provided for each data set with the appropriate statistical methods, representing two or more independent sets of data that showed similar results. Western blot quantification was performed using either ImageQuant TL or ImageJ software (version 1.53a). Graphical drawings were prepared using Adobe Illustrator® (version 2020).

Sample sizes

No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes, but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications33,51,52.

Competing Interests Statement

All authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Data distribution

Data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested.

Randomization

Mice of C57BL/6 inbred strain were randomly assigned to various groups.

Blinding

Data collection and analysis were not performed blind to the conditions of experiment.

Data exclusion

No data exclusions from analyses were made.

Study approval

All experiments were conducted in accordance with approved protocols by the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Accession code

Microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus with accession code number GSE17518.

Data Availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Extra data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

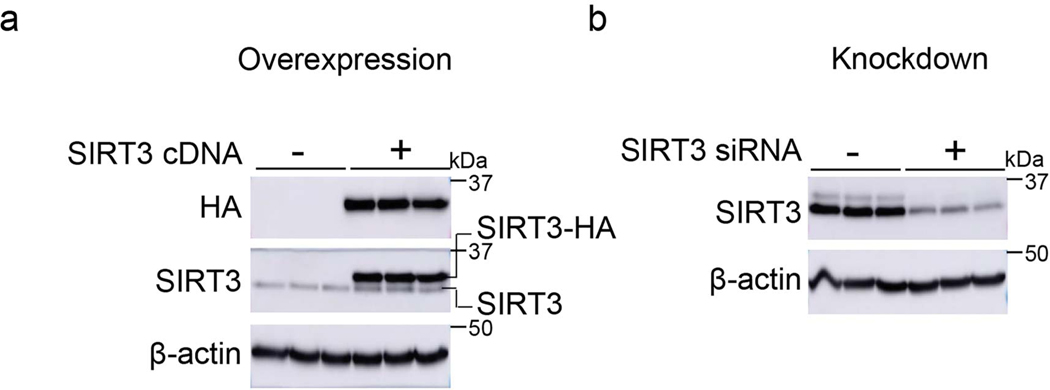

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. SIRT3 antibody specifically recognizes SIRT3 protein.

(a) Western blot showing over expression of HA tagged SIRT3 in human fibroblasts transfected with control or SIRT3 cDNA plasmid. (b) Western blot showing expression levels of SIRT3 in human fibroblasts transfected with non-targeting or SIRT3 siRNA. SIRT3 and HA antibodies were used to probe SIRT3 or SIRT3-HA expression levels.

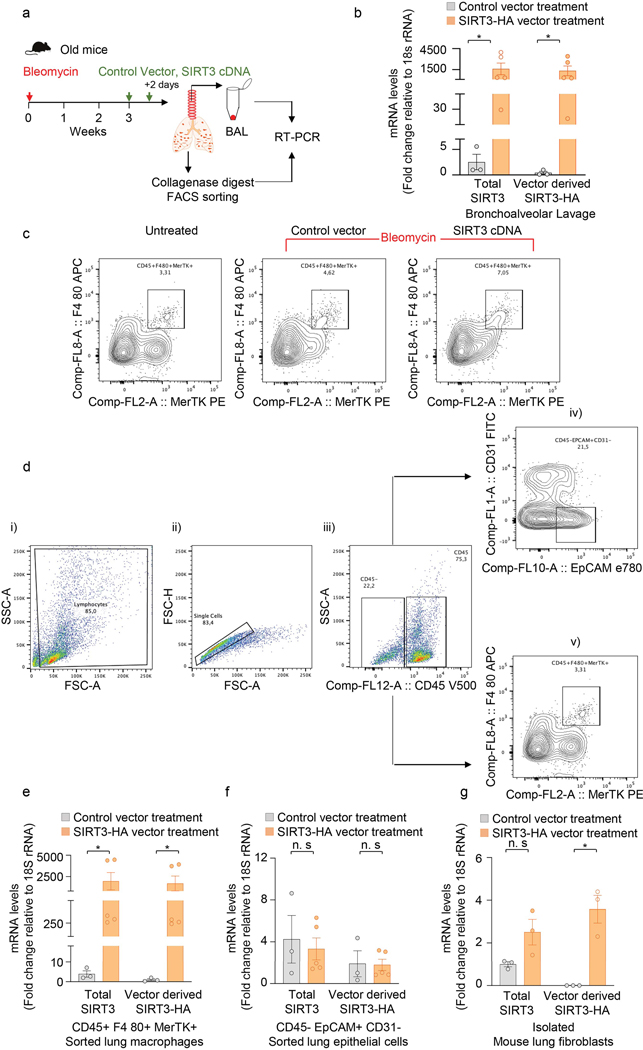

Extended Data Fig. 2. Exogenous SIRT3 cDNA is preferentially expressed in lung macrophages.

(a) Schematic of experiment design. (b) RT-PCR analysis of total SIRT3 or vector derived SIRT3-HA mRNA levels in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) from mice subjected to bleomycin injury followed by treatment with control vector (n = 3) or SIRT3 cDNA plasmid (n = 5), as indicated in the Methods section. Data presented as means ± s.e.m., *P =0.0357 (unpaired t-test, non-parametric, two-tailed). (c) Flow cytometric analysis of macrophages (CD45+ F4 80+ MerTK+) sorted from collagenase lung digests of naïve mice and mice injured with bleomycin followed by treatment with control vector or SIRT3 cDNA are shown. (d) Gating strategy: (i) cells were gated for FSC-A against SSC-A; (ii) doublets were excluded using FSC-H against FSC-A; (iii) singlets were gated for CD45 positive/negative population; (iv) within the CD45- population, epithelial cells were gated as EPCAM+CD31-; and (v) within the CD45+ population, macrophages were gated as F480+MerTK+. (e-g) RT-PCR analysis of total SIRT3 or vector derived SIRT3-HA mRNA levels in FACS sorted macrophages (e) and epithelial cells (f), and adherence-purified fibroblasts (g) from whole lung collagenase digest from mice subjected to bleomycin injury followed by treatment with control vector (n = 3) or SIRT3 cDNA plasmid (n = 5). Data presented as means ± s.e.m., *P = 0.0357 (macrophages;unpaired t-test, non-parametric, two-tailed), P = 0.0052 (fibroblasts; unpaired t-test, two-tailed statistical analysis), n.s. = not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 3. TGF-β1 downregulates SIRT3 and FoxO3a levels in human fibroblasts.

Top panel, schematic diagram showing experiment design. Bottom panel, western blots demonstrating early and late downregulation of SIRT3 and FoxO3a, respectively, and upregulation of α-SMA at indicated time points in TGF-β1 treatment of human fibroblasts.

Extended Data Fig. 4. FoxO3a overexpression in IPF fibroblasts induces Noxa and inhibits Col1a1.

Western blots and quantitative analysis of FoxO3a, cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP, Noxa and Col1a1 protein levels in IPF fibroblasts transfected with control plasmid or FoxO3a cDNA. n = 3 per group; Data presented as means ± s.e.m., P values as indicated by unpaired t-test, two-tailed statistical analysis.

Extended Data Fig. 5. The effects of SIRT3 overexpression on FoxO3a levels in control and IPF fibroblasts.

(a) Left panel, schematic of experiment design. Right panel, western blot showing levels of SIRT3 and FoxO3a in IMR-90 fibroblasts and IPF fibroblasts overexpressing control or SIRT3 plasmid. (b) Left panel, schematic diagram of experiment design. Right panel, western blot showing SIRT3 and FoxO3a levels in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of human fibroblasts overexpressing SIRT3 at 24 and 48 hours after transfection.

Extended Data Fig. 6. The effects of SIRT3 overexpression on FoxO3a recovery in TGF-β1 treated human lung fibroblasts.

(a) Left panel, schematic of the experiment design. Right panel, representative western blot showing levels of HA tag, SIRT3, FoxO3a and α-SMA in human fibroblasts cells transfected with SIRT3-HA plasmid followed by treatment with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) for 48 hours. (b) Left panel, schematic diagram of the experiment design. Right panel, representative western blot analyses of HA, SIRT3, FoxO3a and α-SMA in IMR-90 cells treated with TGF-β1 for 48 hours followed by SIRT3 overexpression.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Effects of conditioned media from SIRT3-overexpressing human and mouse lung epithelial cells on FoxO3a levels in human lung fibroblasts.

(a) Schematic of the experimental design. (b) Left panel, representative western blot showing overexpression of SIRT3 in A549 cells. Right panel, western blot showing levels of FoxO3a in human fibroblasts incubated with the conditioned media from SIRT3-overexpressing A549 cells. Cond. Med. = conditioned media (c) Left panel, western blot showing overexpression of SIRT3 in L2 mouse epithelial cells. Right panel, representative western blot showing levels of FoxO3a in IMR-90 fibroblasts incubated with conditioned media from SIRT3-overexpressing L2 cells at 48 hours. Cond. Med. = conditioned media.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Effects of conditioned media from SIRT3-overexpressing macrophages (THP1 or RAW264.7 cells) on FoxO3a levels in human fibroblasts.

(a) Schematic of the experimental design. (b) Left panel, representative western blot showing overexpression of SIRT3 in human macrophage line THP1 cells. Right panel, western blot showing expression of FoxO3a in human fibroblasts incubated with conditioned media of SIRT3 overexpressing THP1 cells. Cond. Med. = conditioned media. (c) Left panel, western blot showing overexpression of SIRT3 in RAW264.7 mouse macrophages. Right panel, western blot showing levels of FoxO3a in fibroblasts incubated with conditioned media of SIRT3 overexpressing RAW264.7 cells at 48 hours. Cond. Med. = conditioned media.

Extended Data Fig. 9. FoxO3a levels in young and aged mouse fibroblasts co-cultured with SIRT3 overexpressing L2 cells.

(a) Schematic of the experiment design; FB = fibroblasts. (b) Representative western blots indicate SIRT3 levels in whole cell lysates of L2 cells (b), FoxO3a levels in the cytoplasm (c), and in nuclear fractions (d) from young and old mouse fibroblasts. Fibroblasts were co-cultured with L2 cells that overexpress SIRT3 or control plasmid.

Extended Data Fig. 10. Cytokine array of secreted factors by SIRT3 overexpressing macrophages.

Mouse XL cytokine array and quantitative analysis performed on cell supernatants of co-cultured SIRT3-overexpressing macrophages and mouse fibroblasts.

Supplementary Material

Figure 8: Airway delivery of SIRT3 cDNA resolves age-associated persistent lung fibrosis in mice.

Aged mice subjected to bleomycin lung injury develop persistent, non-resolving lung fibrosis. This non-resolving phenotype of lung injury-fibrosis is associated with decreased lung levels of SIRT3 and persistence of apoptosis-resistant myofibroblasts. Gene delivery of SIRT3 cDNA via the airway restores capacity for fibrosis resolution, which is associated with FoxO3 activation/translocation to the nucleus. Our studies support a cell non-autonomous mechanism by which airway macrophages uptake the SIRT3 cDNA plasmid and produce pro-resolution factor(s) that are able to activate FoxO3a in myofibroblasts and mediate anti-senescent and pro-apoptotic effects in these reparative cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants P01 HL114470, R01 AG046210 (to VJT); R01 HL139617 (to JWZ and VJT); US Department of Defense grant W81XWH-17-1-0577 (to JWZ); and a US Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Award I01BX003056 (to VJT). We thank Yong Wang for her assistance in FACS experiment.

References

- 1.Thannickal VJ, Zhou Y, Gaggar A. & Duncan SR Fibrosis: ultimate and proximate causes. J Clin Invest 124, 4673–4677 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thannickal VJ, Toews GB, White ES, Lynch JP 3rd & Martinez FJ Mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. Annu Rev Med 55, 395–417 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wynn TA & Ramalingam TR Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med 18, 1028–1040 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapetanaki MG, Mora AL & Rojas M. Influence of age on wound healing and fibrosis. J Pathol 229, 310–322 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thannickal VJ Mechanistic links between aging and lung fibrosis. Biogerontology 14, 609–615 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newgard CB & Sharpless NE Coming of age: molecular drivers of aging and therapeutic opportunities. J Clin Invest 123, 946–950 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrucci L, et al. Measuring biological aging in humans: A quest. Aging Cell 19, e13080 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodell MA & Rando TA Stem cells and healthy aging. Science 350, 1199–1204 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghu G, Chen SY, Hou Q, Yeh WS & Collard HR Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US adults 18–64 years old. Eur Respir J 48, 179–186 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy BK, et al. Geroscience: linking aging to chronic disease. Cell 159, 709–713 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thannickal VJ, et al. Blue journal conference. Aging and susceptibility to lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 191, 261–269 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M. & Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153, 1194–1217 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willcox BJ, et al. FOXO3A genotype is strongly associated with human longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 13987–13992 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broer L, et al. GWAS of longevity in CHARGE consortium confirms APOE and FOXO3 candidacy. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 70, 110–118 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose G, et al. Variability of the SIRT3 gene, human silent information regulator Sir2 homologue, and survivorship in the elderly. Exp Gerontol 38, 1065–1070 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Ven RAH, Santos D. & Haigis MC Mitochondrial Sirtuins and Molecular Mechanisms of Aging. Trends Mol Med 23, 320–331 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.North BJ & Verdin E. Sirtuins: Sir2-related NAD-dependent protein deacetylases. Genome Biol 5, 224 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haigis MC & Guarente LP Mammalian sirtuins--emerging roles in physiology, aging, and calorie restriction. Genes Dev 20, 2913–2921 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onyango P, Celic I, McCaffery JM, Boeke JD & Feinberg AP SIRT3, a human SIR2 homologue, is an NAD-dependent deacetylase localized to mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 13653–13658 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Someya S, et al. Sirt3 mediates reduction of oxidative damage and prevention of age-related hearing loss under caloric restriction. Cell 143, 802–812 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirschey MD, et al. SIRT3 deficiency and mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation accelerate the development of the metabolic syndrome. Mol Cell 44, 177–190 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu W, et al. Loss of SIRT3 Provides Growth Advantage for B Cell Malignancies. J Biol Chem 291, 3268–3279 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam EW, Brosens JJ, Gomes AR & Koo CY Forkhead box proteins: tuning forks for transcriptional harmony. Nat Rev Cancer 13, 482–495 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paik JH, et al. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell 128, 309–323 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tseng AH, Shieh SS & Wang DL SIRT3 deacetylates FOXO3 to protect mitochondria against oxidative damage. Free Radic Biol Med 63, 222–234 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kops GJ, et al. Forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a protects quiescent cells from oxidative stress. Nature 419, 316–321 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Tamari HM, et al. FoxO3 an important player in fibrogenesis and therapeutic target for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. EMBO Mol Med 10, 276–293 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nho RS, Hergert P, Kahm J, Jessurun J. & Henke C. Pathological alteration of FoxO3a activity promotes idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis fibroblast proliferation on type i collagen matrix. Am J Pathol 179, 2420–2430 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jablonski RP, et al. SIRT3 deficiency promotes lung fibrosis by augmenting alveolar epithelial cell mitochondrial DNA damage and apoptosis. FASEB J 31, 2520–2532 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sosulski ML, Gongora R, Feghali-Bostwick C, Lasky JA & Sanchez CG Sirtuin 3 Deregulation Promotes Pulmonary Fibrosis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 72, 595–602 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rangarajan S, et al. Metformin reverses established lung fibrosis in a bleomycin model. Nat Med 24, 1121–1127 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGlynn LM, et al. SIRT3 & SIRT7: Potential Novel Biomarkers for Determining Outcome in Pancreatic Cancer Patients. PLoS One 10, e0131344 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hecker L, et al. Reversal of persistent fibrosis in aging by targeting Nox4-Nrf2 redox imbalance. Sci Transl Med 6, 231ra247 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hinz B. & Lagares D. Evasion of apoptosis by myofibroblasts: a hallmark of fibrotic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 16, 11–31 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sundaresan NR, et al. Sirt3 blocks the cardiac hypertrophic response by augmenting Foxo3a-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms in mice. J Clin Invest 119, 2758–2771 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirkwood TB Understanding the odd science of aging. Cell 120, 437–447 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horowitz JC & Thannickal VJ Mechanisms for the Resolution of Organ Fibrosis. Physiology (Bethesda) 34, 43–55 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sundaresan NR, et al. SIRT3 Blocks Aging-Associated Tissue Fibrosis in Mice by Deacetylating and Activating Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3beta. Mol Cell Biol 36, 678–692 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srivastava SP, et al. SIRT3 deficiency leads to induction of abnormal glycolysis in diabetic kidney with fibrosis. Cell Death Dis 9, 997 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferber EC, et al. FOXO3a regulates reactive oxygen metabolism by inhibiting mitochondrial gene expression. Cell Death Differ 19, 968–979 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou Y, et al. Inhibition of mechanosensitive signaling in myofibroblasts ameliorates experimental pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 123, 1096–1108 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lagares D, et al. Targeted apoptosis of myofibroblasts with the BH3 mimetic ABT-263 reverses established fibrosis. Sci Transl Med 9(2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanders YY, et al. Histone modifications in senescence-associated resistance to apoptosis by oxidative stress. Redox Biol 1, 8–16 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kato M, et al. Role of the Akt/FoxO3a pathway in TGF-beta1-mediated mesangial cell dysfunction: a novel mechanism related to diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17, 3325–3335 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wynn TA & Vannella KM Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity 44, 450–462 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bitterman PB, Wewers MD, Rennard SI, Adelberg S. & Crystal RG Modulation of alveolar macrophage-driven fibroblast proliferation by alternative macrophage mediators. J Clin Invest 77, 700–708 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cui H, et al. Monocyte-derived alveolar macrophage apolipoprotein E participates in pulmonary fibrosis resolution. JCI Insight 5(2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larson-Casey JL, Deshane JS, Ryan AJ, Thannickal VJ & Carter AB Macrophage Akt1 Kinase-Mediated Mitophagy Modulates Apoptosis Resistance and Pulmonary Fibrosis. Immunity 44, 582–596 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joshi N, et al. A spatially restricted fibrotic niche in pulmonary fibrosis is sustained by M-CSF/M-CSFR signalling in monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages. Eur Respir J 55(2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bao L, et al. The pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 in hACE2 transgenic mice. Nature (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hecker L, et al. NADPH oxidase-4 mediates myofibroblast activation and fibrogenic responses to lung injury. Nat Med 15, 1077–1081 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kurundkar D, et al. SIRT3 diminishes inflammation and mitigates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. JCI Insight 4(2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Extra data are available from the corresponding author upon request.