Abstract

A layered hydroxide salt (LHS) was used as an inorganic matrix to obtain multifunctional food compounds. The aim is to obtain higher thermal stability for vitamin anions and a slow release of aroma. Thus, vitamin B3 (nicotinate), vitamin B5 (phantothenate) and vitamin L (2-aminobenzoate) anions were intercalated by co-precipitation method. The results show an increase in thermal stability of intercalated vitamin anion since decomposition of pure vitamin B3 starts at 120 °C and after intercalation, the HSL-B3 decomposition starts at 313 °C. The intercalation products were than reacted with vanillin (3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzaldehyde). A kinetic study showed that the release of vanillin from its nanohybrid was found to occur in a controlled manner, evidencing that the synthesized compounds can be used in formulations for the sustained release of aromas. Results showed that the intercalated anions and adsolubilized vanillin were not only less volatile since it causes the aroma to remain in the LHS for a longer period of time resulting in slow release but also have higher thermal stability when they are confined between layers. In summary, the multifunctional food supplements obtained seems to have nutraceutical, olfactory and better thermal resistance properties being suitable for potential applications in the food industry.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13197-020-04859-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Layered hydroxide salt, Intercalation, Vitamins, Adsolubilization, Aromas, Multifunctional food supplements

Introduction

Vitamins are a class of nutraceuticals additives, and its use has increased in recent years, especially in industries related to human health. This growth is due to the low or no production of these compounds by human body that gets such compounds from specific food intake (Mougin et al. 2016).

As it is well known, vitamins are essential for the body normal growth and for the maintenance of the cells, tissues, and organs in a multicellular organism. Vitamin B3 or Niacin, for example, has an extreme important function in human metabolism acting in NADP and NAP(H) synthesis, essential nucleotides for respiration process, and also as protection against cardiovascular problems (Kondjoyan et al. 2018).

Panthotenic acid or vitamin B5 also have an important role in metabolism as component of coenzyme A, needed for fatty acid metabolism, production of hormones and cardiovascular protection (Combs et al. 2017).

Also, vitamin L1, 2-aminobenzoic acid or anthranilic acid, despite of not being considered a vitamin, it has an important function acting on synthesis of serotonin, that is fundamental for human lactation and also helps in quinolinic acid synthesis, that protects against oxidative stress and prevent free radicals (Francisco-Marquez et al. 2016).

Considering the importance of vitamins level on processed food, factors like pH, temperature, light, moisture and presence of oxygen are the main responsible for the losses of vitamins during food processing (Kondjoyan et al. 2018). Moreover, there is a major problem considering the stability of these micronutrients facing thermal processes (Combs et al. 2017).

Although many alternative process and products were recently developed, it is not enough to prevent vitamins losses (Kondjoyan et al. 2018; Francisco-Marquez et al. 2016). Thus, this research presents an alternative to stabilize such unstable vitamins by the intercalation of them into layered inorganic lattices such as layered hydroxide salts (LHS).

LHS is a class of layered materials whose structure derived from brucite. It possesses a general formula of M2+(OH)2-x(An−)x/n·nH2O, where M2+ is typically one of the metal cations Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Cd2+ and An− the anion called counter ion, as nitrate, sulfate and chlorate (Arizaga et al. 2007). The exchange between the counter ion present and other anionic specie present in the intercalation compounds (LHS), which not affect its structure, is called topotactic exchange reaction. Different anionic species can be intercalated into LHS based on their structural characteristics and therefore they are classified as anion exchanger (Rajamathi et al. 2003). The advantage of intercalation is improving some specific characteristics when compared to pure compound with the advantage to present an excellent biocompatibility and low toxicity (Del Hoyo et al. 2007; Hwang et al. 2001; Velázquez-Carriles et al. 2020).

Another class of additives that has gain special attention is aromas and they are frequently added to products to improve sensory characteristics (Burgos et al. 2017). The major drawback concerning these compounds is its fast release due to their volatility (Tylewicz et al. 2017). For instance, vanillin is relatively unstable to heat treatments and it has a fast release (Yin et al. 2017). The strategy adopted here to improve the use of aromas as food additives is the adsolubilization.

Adsolubilization is a recent method based on the change of the polarity in the interlayer space after intercalation (Zhao et al. 2015). This change will improve the solubility of non-polar or non-ionic species, and enable the interaction between the neutral molecule of aroma and the vitamins intercalated (Cursino et al. 2013). As a result, this interaction will promote a slow release of the volatile (Chaara et al. 2011).

Therefore, in this paper, we report the adsolubilization of vanillin into vitamin anions intercalated into LSH in order to protect the vitamin from thermal degradation and to obtain a slow release of aromas resulting in a multifunction food supplements providing aroma and nutraceutical properties.

Materials and methods

Organic and inorganic reagents (analytical grade) were used without further purification. Inorganic chemicals such as zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Dinâmica, 96%) and sodium hydroxide (Dinâmica, 98%) were both of guaranteed reagent grade. Also, were used 2-aminobenzoic acid (Reagen, 98%), nicotinic acid (Synth, 99%) and phantothenic acid (Alphatec, 97.5%) as intercalated vitamin anions L, B3 and B5, respectively. As representative for aroma was selected the 3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzaldehyde or vanillin (Alphatec, 98%).

Synthesis of layered zinc hydroxide salts containing intercalated vitamin anions

An intercalation compound with vitamin anions was made by co-precipitation reaction by dissolving 0.08 mol of vitamins (nicotinic acid—vitamin B3, 2-aminobenzoic acid—vitamin L and phantothenic acid—vitamin B5) in 80 mL of an aqueous solution of NaOH (1 mol L−1), resulting in vitamin anions. Based on the expected formula of the LHS (Zn5(OH)8(V)2·nH2O), where V is the vitamin anion, and to guarantee that the nitrate anions was exchanged by vitamin anions, fourfold of the vitamin anion molar content was used in relation to zinc. The vitamin anions solution was add to a 0.05 mol of Zn(NO3)2 solution and the final pH was adjusted to 6.7 by the addition of NaOH (1 mol L−1) solution. The dispersion was magnetically stirred at room temperature (30 °C) for 1 day. Later, this dispersion was centrifuged and washed with distilled water several times. The products were dried at 60 °C for 24 h, yielding the products LHS/B3 (zinc hydroxide salt intercalated with vitamin B3), LHS/L (zinc hydroxide salt intercalated with vitamin L) and LHS/B5 (zinc hydroxide salt intercalated with vitamin B5). The co-precipitation solid with vanillin was made the same way, using the aroma instead of vitamin, abbreviated as LHS/VN.

Preparation of the adsolubilized compounds

After characterization, 2 mmol of the layered zinc hydroxide salts intercalated with the vitamins were submitted to the adsolubilization process with vanillin (6 mmol) as previously reported by Cursino et al. (2013). Based again on the ideal formulation, this amount of vanillin represents an excess of three times the theoretical content of the intercalated capacity. Vanillin is a volatile compound and to avoid losses, the mixture was added to a static Teflon vessel inside a steel reactor at room temperature (30 °C) for 15 days. The compounds were washed three times with ethyl ether, centrifuged twice at 3000 rpm for 3 min and dried at room temperature. The adsolubilized compounds are abbreviated as LHS/B3-VN, LHS/L-VN and LHS/B5-VN, depending on the intercalated vitamin.

Characterization

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained with an Empyrean diffractometer from Panalytical using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) with 30 mA and 40 kV. The samples were placed and oriented by gently hand pressing on a silicon low background sample holder.

The Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded in a Perkin Elmer model Spectrum 100 s Spectrometer instrument, with attenuated total reflectance attachment using a zinc selenide crystal. The measurements were performed in transmission mode with accumulation of 4 scans and recorded with a nominal resolution of 4 cm−1.

Thermogravimetric (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) were carried out with a STA 6000 Thermal-Analyzer instrument, from Perkin-Elmer, in flowing oxygen at 20 mL min−1 and a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 until 900 °C. The mass of samples used were weighed ranging from 6 to 8 mg.

The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained at a JEOL JSM-6701F instrument with a field emission guns (FEG). Powder samples were dropped on a copper double-sized tape and the samples were coated with a thin layer of gold.

Elemental analysis was performed to determine the quantity of intercalated vitamin into inorganic matrix using a Perkin–Elmer series II CHNS/O analyzer (model 2400) coupled to a Perkin–Elmer AD 6000 autobalance and controlled by EA 2400 data Manager software.

Release kinetics of vanillin

After confirming the adsolubilization, it was examined the retention stability of vanillin according to a modified methodology reported by Ahmad et al. (2015), were 30 mg of the product were added in 50 ml of deionized water, simulating a neutral condition of a food. From this dispersion, aliquots were taken periodically and the amount of released vanillin was determined by monitoring the variation of absorbance peak at 309 nm. Absorption spectral measurements were carried out with a PerkinElmer Model Lambda XLS UV–Vis spectrophotometer.

Different kinetic models were employed to fit the aroma release behavior and to verify what model best fit with the results. The tested models were Elovich, Modified Freundlich, Bhaskar and Parabolic Diffusion.

Results and discusion

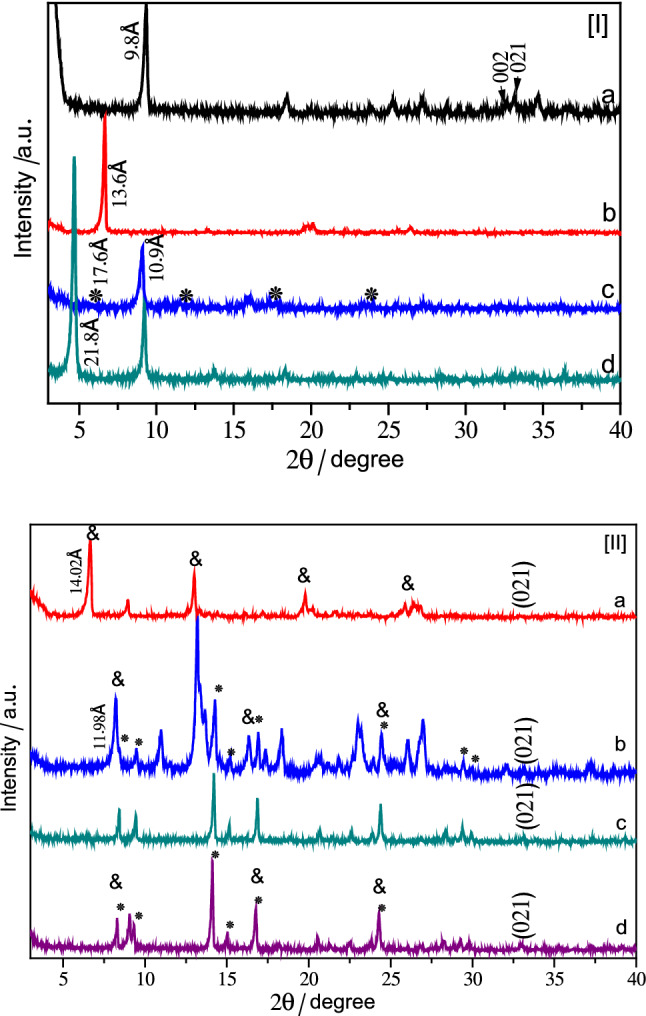

The XRD patterns of the layered zinc hydroxide salts intercalated with vitamins (Fig. 1[I]) correspond to the crystalline phase of layered zinc hydroxide nitrate (ZHN), Zn5(OH)8(NO3)2·2H2O, identified by the JCPDS file number 24–1460.19, due to the presence of two characteristic non-basal maxima corresponding to diffraction planes (002) and (021) at 2θ values of 32.5° and 33.0°, respectively (Stählin and Oswald, 1971). The LHS pattern (Fig. 1[I]a) is characterized by an intense and sharp reflection at 9.7 Å, due to the (200) plane reflection of the monoclinic structure (Demel et al. 2011).

Fig. 1.

XRD patterns of I intercalation products—a ZHN, b LHS/L, c LHS/B3, d LHS/B5 and II adsolubilization products—a LHS/L-VN, b LHS/B3-VN, c LHS/B5-VN, d control reaction with LHS and vanillin (LHS/VN)

The layered structure showed a displacement of the basal distance from 9.7 Å (Fig. 1[I]a) to 21.8 Å (Fig. 1[I]d) and 13.6 Å (Fig. 1[I]b) for LHS intercalated with vitamin B5 (LHS/B5) and vitamin L (LHS/L), respectively, after contact with the vitamin, which corresponds to an opening of the interlayer space of 14.4 Å and 6.2 Å, which are expected for the intercalation of these vitamins in an interdigitated monolayer arrangement. The monolayer arrangement to the LHS/L, for example, was proposed based on the basal spacing of 13.6 Å calculated using X-ray data, and subtracting the thickness of the brucite layer (4.8 Å) and also 2.6 Å for each zinc tetrahedron, the gallery height was 6.2 Å, which is close to the y-axis of vitamin L (2-aminobenzoate) (6.0 Å) [Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Information section].

Compounds intercalated with the nicotinic acid (LHS/B3), probably a mixture of two phases were obtained (Hwang et al. 2001). The main one with a basal distance of 10.9 Å and a secondary one (marked with asterisks) with a basal distance of 17.6 Å (Fig. 1[I]c). These basal distances are consistent with the allocations of one layer and two layers of the intercalated vitamins anions between the layers, respectively (Hwang et al. 2001).

The X-ray powder diffraction patterns of the intercalation products do not show peaks of pure vitamins or vitamins sodium salts (not show). In addition to increasing the basal distance, this indicates that there are no free vitamins in the intercalation product.

The X-ray powder diffraction patterns of the vanillin adsolubilized products, LHS/L-VN (Fig. 1[II]a) and LHS/B3-VN (Fig. 1[II]b), presented a good crystallinity and it was possible to verify increases in the basal spacing compared to the precursors LHS/B3 and LHS/L. The increase in basal spacing for LHS/L-VN and LHS/B3-VN were 0.42 Å and 1.04 Å, respectively. This can be attributed to the accommodation of the adsolubilized vanillin between intercalated vitamin anions, adjusting their position to a new condition as observed by Cursino et al. (2013) [Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Information section]. The preservation of the layered structure of the matrix is confirmed by the presence of the basal reflections, in the direction of layer stacking (h00), which are uniformly distributed between 5 and 30 of 2θ (degrees) indicated by ampersand (&) (Fig. 1[II]). The characteristic diffraction by non-basal plane (021) was also recorded.

A mixture of two phases was obtained in the adsolubilized compound LHS/B3-VN. The main one with a basal distance of 11.98 Å with vanillin adsolubilized and a secondary one (marked with asterisks) with vanillin intercalated (Fig. 1[II]b).

The XRD pattern to the vanillin adsolubilization into LHS/B5 (Fig. 1[II]c) was completely different from the precursor (LHS/B5), although similar to the pattern obtained with pure vanillin intercalation (LHS/VN) (Fig. 1[II]d). This indicates that the vitamin B5 anions were totally exchanged by the vanillin. Vanillin is a very weak acid compound based on its pKa and that is why vanillin anions exchange the vitamin B5 anions. This may have occurred, because vitamin B5 anions are not necessarily linked with the layered, so they can interact by electrostatic forces. In addition, the pantetonate anions is relatively large compared to other vitamins (B3 and L) anions, this can reduce its stability in the interlayer environment which facilitates ion exchange.

No evidence of crystalline vanillin was detected in the XRD patterns (not show). In spite of this, the presence of vanillin was evidenced by FTIR spectroscopy [Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Information section].

The presence of the vitamins intercalated into the matrix, such as B3 in the product LHS/B3 (Fig. S3(b)), is further evidenced by the antisymmetric and symmetric stretching of C–O bonds on carboxylate groups at 1550 cm−1 and 1385 cm−1. In addition, bands at 1600 cm−1 and 1665 cm−1 were also detected, which can be attributed to carbon–carbon stretching vibrations in the aromatic ring and carbonyl stretching vibration band C=O of aldehyde, respectively (Chesalov et al. 2013).

The FTIR spectra of the product LHS/L shows bands at 1591 and 1409 cm−1, which can be attributed to symmetric and antisymmetric C–O bonds on carboxylate groups. It is possible observe the presence of N–H bond peaks of primary ammines at 3127 and 3298 cm−1 and a characteristic band of ammine bonded to aromatic ring at 1326 cm−1 (Fig. S3(a)) (Nakamoto, 1986).

In the spectrum of LHS/B5 (Fig. S3(c)), two bands are observed, at 2967 and 2877 cm−1, attributed to primary amine N–H bonds. Also, a band at 1629 cm−1 from carboxylic groups, displaced relative to the pure vitamin (1651 cm−1) indicates the presence of the vitamin B5 in the interlayer space as reported in the literature (Srivastava et al. 2014).

In the adsolubilized compounds spectra, LHS/B3-VN (Fig. S3(e)) and LHS/L-VN (Fig. S3(d)), it was possible to identify characteristic bands of vanillin like the band at 1665 cm−1 attributed to carbonyl stretching vibration band C=O of aldehyde and at 1510 cm−1 attributed to carbon–carbon stretching vibrations in the aromatic ring (Srivastava et al. 2014; Sundaraganesan et al. 2007). The symmetric and antisymmetric stretch of aryl alkyl ether corresponds to the bands at 1200 cm−1 e 1155 cm−1 respectively (Nakamoto, 1986). The FTIR of the LHS/B5-VN (Fig. S3(f)) compound showed no evidence of vitamin B5 as the spectra was similar to the intercalation product LHS/VN. Bands characteristics of vanillin with small shifts were observed, proving that vitamin B5 was replaced by the vanillin.

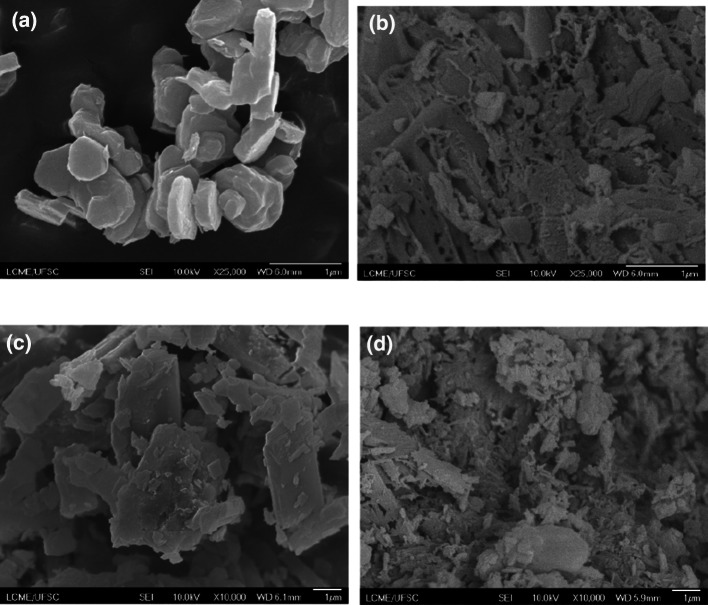

Morphological analyses of the LHS/L and LHS/B3, with and without vanillin, were performed by FE-SEM and the micrographs are shown in Fig. 2. The co-precipitated LHS/L (Fig. 2a) was characterized by tabular particles with elongated hexagonal and the particles seem a bit thicker. The LHS/B3 (Fig. 2c) consists of plate-like particles. Their size was not accurately determined but SEM micrographs show that a 3 μm size is easily attained.

Fig. 2.

SEM images of a LHS/L, b LHS/L-VN, c LHS/B3 and d LHS/B3-VN

In contrast, the micrograph for the adsolubilization product LHS/L-VN (Fig. 2b) shows that particles formed aggregated probably due to mixture of phases, one crystalline and another amorphous. In the LHS/B3-VN compound (Fig. 2d) the aggregated is due to mixture of two phases one with vanillin adsolubilized and a secondary one with vanillin intercalated, as previously discussed.

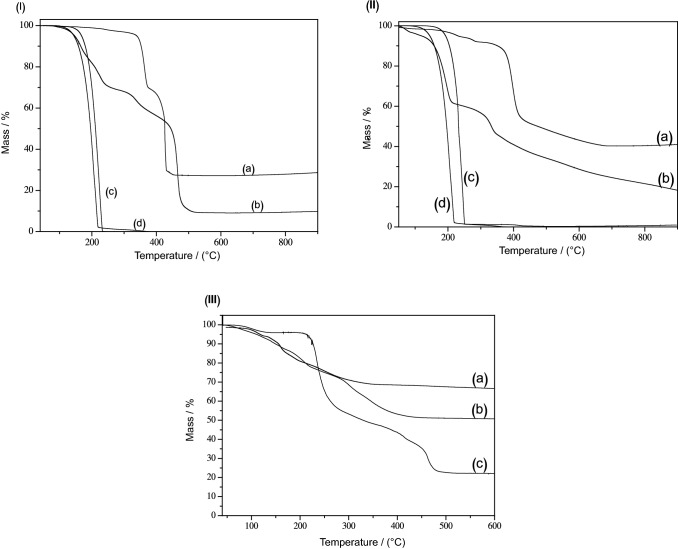

In the TGA curves (Fig. 3), it was possible to identify different behaviors between pure vitamin, intercalated vitamin anions products and intercalated vitamins/aroma adsolubilization products suggesting distinct chemical compositions. The thermal decomposition profile of LHS/L shows two main events, the first one corresponding to the removal of water up to 200 °C and the second one to the burning of organic matter and dehydroxylation of the matrix. The second decomposition step is associated with an intense exothermic peak at 428 °C [Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Information section]. It is important to note that for the 2-aminobenzoic acid (Fig. 3Ic), its thermal decomposition begins at 129 °C, with complete degradation at 226 °C, showing an improvement in the thermal stability of vitamin L after intercalation.

Fig. 3.

Thermal analysis (TGA) curves of I a—LHS/L, b—LHS/L-VN, c—pure vitamin L, d—vanillin; II a—LHS/B3, b—LHS/B3-VN, c—pure vitamin B3, d—vanillin; III a—pure LHS, b—LHS/B5, c—pure vitamin B5

Vitamin B3 and B5 showed improved thermal stability after intercalation. The decomposition of pure vitamins B3 and B5 was initiated at 155 °C and 199 °C (Fig. 3 II and III), respectively. After intercalation, the thermal decomposition of LHS/B3 and LHS/B5 started above 330 °C and 267 °C, respectively.

In order to estimate the composition of the intercalation compounds, LHS/B3 and LHS/L, elemental analysis and TGA/DSC measurements were performed. It was considered two main thermal events, the first corresponding to the removal of physisorbed/intercalated water molecules and dehydroxylation of the layered matrix. The second thermal event is attributed to the oxidation of organic matter, producing ZnO. Table S1 [Table S1 in the Supplementary Information section] shows the percentages of mass loss and their temperature range observed from the thermal analysis curves, as well as carbon and nitrogen contents obtained from elemental analysis, with this information it was possible to estimate the composition of the compounds as being Zn5(OH)8(NO3)0.15(C6H4NO2)1.85·5H2O to LHS/B3 and Zn5(OH)8(C7H6NO2)4.46·22 H2O to LHS/L.

Additionally, we have investigated the release behavior of adsolubilized vanillin. The total amount of vanillin released was 8.3 × 10–2 mol L−1 and 0.107 mol L−1 per gram of compound LHS/B3-VN and LHS/L-VN, respectively, and it was assumed that the maximum amount of vanillin released was the total amount of vanillin adsolubilized/intercalated. It was observed by the kinetic curves (Fig. 4) that approximately 80% of vanillin was released in within 24 h, followed by an even slower and sustained adsolubilization of vanillin. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first time that the release kinetics of adsolubilized vanillin in a layered compounds (layered hydroxide salt and layered double hydroxides) was studied, but the intercalation into layered double hydroxides (LDH) has been studied before. Layered double hydroxides have the general formula (M2+1−xM3+x(OH)2(Am−)x/m·nS), where M2+ and M3+ are metal cations and Am− is an exchangeable inorganic or organic anion that compensates the positive charge of the layer and n are the moles of solvent S, usually water. An intercalated anion can be replaced by another via ion-exchange. In the hydroxide salts, the situation is similar to that of LDH, but due to the replacement of hydroxyl groups by other ions, they become exchangeable and only one metal is involved. For example, Khan and co-workers intercalated vanillin into LDH (h-LiAl2–Cl) using an ion exchange approach in order to studied the release of the fragrance and results depicted that the time taken for 90% of vanillin (1.78 × 10–3 mol L−1 per gram of h-LiAl2-Cl) to be released was 11 min (Khan et al. 2009). Also, Silion and co-workers studied the release of vanillic acid (VA) from LDH (Zn/Al) and, at pH 7.4, 65% of VA was released after 820 min (1.65 × 10–2 mol L−1 per gram of intercalated compost). However, in the study, the maximum amount of released VA was 70% (Silion et al. 2012). Herein, we observed from Fig. 4 that the time taken to the release reach equilibrium from both compounds was approximately 37 h (2280 min), which is a promising result compared to these and other studies with HDLs and the release of interspersed or adsorbed molecules (Gasser et al. 2009; Rojas et al. 2012). Also, the amount of vanillin released is considerably higher than the amount of vanillin on the mentioned studies.

Fig. 4.

Vanillin release from LHS/L and LHS/B3

This stabilization is an evidence of the interaction between layered compound and aroma molecules, which avoids the loss of volatile to water (Gao et al. 2013). After this stabilization period, the degradation of the aroma began as observed in the pure compound, but in pure vanillin the degradation begins with 10 h of exposure to the medium. The similar release behavior of vanillin from both compounds indicates that the interaction between vanillin and both B3 and L vitamins is equally strong despite their different molecule structure.

The release profile data were fitted (Fig. 5a–d) using the kinetic models presented in Table 1 that summarizes the parameters obtained including the rate constant k. In all the equations, Mt/Mi indicates the fraction of released vanillin at time t. The linear correlation coefficient R2 values obtained were greater than 0.89, except for the Modified Freundlich Model. It is evident that the best model to describe the release of vanillin in LHS/B3-VN and LHS/L-VN is Bhaskar model, which sheds light to the release mechanism suggesting that the process is diffusion-controlled via intra-particle diffusion (Bhaskar et al. 1986; Djaballah et al. 2018).

Fig. 5.

Models of kinetics release of aroma from LHS/L-VN and LHS/B3-VN a Elovich model, b Modified Freundlich model, c Bhaskar model and d Parabolic Diffusion model

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters obtained for vanillin release from LHS/B3-VN and LHS/L-VN

| Equation | LHS/B3-VN | LHS/L-VN |

|---|---|---|

| Elovich model | ||

| −0.15228 | −0.17676 | |

| 1.33613 | 1.44057 | |

| R2 | 0.90066 | 0.96802 |

| Modified Freundlich model | ||

| 10.004 | 9.140 | |

| −0.60874 | −0.60652 | |

| R2 | 0.74179 | 0.82573 |

| Bhaskar model | ||

| 0.00667 | 0.00847 | |

| R2 | 0.94195 | 0.99015 |

| Parabolic diffusion model | ||

| 0.23688 | 0.21123 | |

| −0.00737 | 0.00681 | |

| R2 | 0.89077 | 0.89017 |

Conclusions

The vitamins—vitamin B3 (nicotinate), vitamin B5 (phantothenate) and vitamin L (2-aminobenzoate)—in their anionic forms were intercalated between the layers of zinc hydroxide nitrate by co-precipitation reaction. The XRD, FTIR, TGA/DSC and SEM confirmed intercalation of the vitamins. TGA/DSC curves confirm an increase of 299 °C, 175 °C and 68 °C in the thermal stability to the vitamins L, B3 and B5 intercalated, respectively, in relation to these vitamins without intercalation.

Adsolubilization of vanillin into LHS intercalated with vitamin anions was verified, due to a small increase of the basal spacing, for LHS/B3-VN and LHS/L-VN samples. The LHS/B3-VN compound presented a mixture of two phases, one with vanillin adsolubilized and a secondary one with vanillin intercalated, was obtained. In the case of LHS/B5-VN compound, the B5 anions were totally exchanged by the vanillin anions.

The FTIR spectra of the adsolubilization products presented bands characteristic of vanillin indicating the presence of the compound in the interlayer space. The total amount of vanillin released was 8.3 × 10–2 mol L−1 and 0.107 mol L−1 per gram of compound LHS/B3-VN and LHS/L-VN, respectively. The release of vanillin from its nanohybrid was found to occur in a controlled manner and the time taken to the release of vanillin from both compounds to reach equilibrium was approximately 2280 min, which is an outstanding result concerning the release of adsolubilized molecules.

It was observed that organic molecules (vitamins/aromas) have higher thermal stability and slow release when they are confined between layers. In summary, the multifunctional food supplements obtained have nutraceutical, olfactory and better thermal resistance properties being suitable for potential applications in the food industry.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Brazilian research agencies CNPq, CAPES and Fundação Araucária for their financial support of this work. The authors also would like to acknowledge the LCME-UFSC for technical support during electron microscopy work and the Central de Análises—QMC/UFSC for the Elemental Analysis.

Author contributions

ACTC conceived, supervised the work and wrote the MS; NCZ carried out the experiments; RMG supervised the work and wrote the MS; RLOB carried out XDR analyses and edited the manuscript; DZM carried out MEV analyses and edited the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ana Cristina Trindade Cursino, Email: anacursino@utfpr.edu.br.

Natália Cristina Zanotelli, Email: natalia.zanotelli@hotmail.com.

Renata Mello Giona, Email: renatam@utfpr.edu.br.

Rodrigo Leonardo de Oliveira Basso, Email: rodrigo.basso@unila.edu.br.

Daniela Zambelli Mezalira, Email: daniela.z.m@ufsc.br.

References

- Ahmad R, Hussein MZ, Kadir WRWA, Sarijo SH, Taufiq-Yap YH. Evaluation of controlled-release property and phytotoxicity effect of insect pheromone zinc-layered hydroxide nanohybrid intercalated with hexenoic acid. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:10893–10902. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arizaga GGC, Satyanarayana KG, Wypych F. Layered hydroxide salts: synthesis, properties and potential applications. Solid State Ionics. 2007;178:1143–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2007.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar R, Murthy RSR, Miglani BD, Viswanathan K. Novel method to evaluate diffusion controlled release of drug from resinate. Int J Pharm. 1986;28:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0378-5173(86)90147-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos N, Mellinas AC, García-Serna E, Jiménez A. Nanoencapsulation of flavor and aromas in food packaging. Food Packag. 2017 doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804302-8.00017-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaara D, Bruna F, Ulibarri MA, Draoui K, Barriga C, Pavlovic I. Organo/layered double hydroxide nanohybrids used to remove non ionic pesticides. J Hazard Mater. 2011;196:350–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesalov YA, Chernobay GB, Andrushkevich TV. FTIR study of the surface complexes of β-picoline, 3-pyridine-carbaldehyde and nicotinic acid on sulfated TiO2 (anatase) J Mol Catal A Chem. 2013;373:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.molcata.2013.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Combs GF, McClung JP. The vitamins. USA: Elseiver; 2017. General properties of vitamins; pp. 33–58 . [Google Scholar]

- Cursino ACT, Lisboa FS, Pyrrho AS, de Sousa VP, Wypych F. Layered double hydroxides intercalated with anionic surfactants/benzophenone as potential materials for sunscreens. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2013;397:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2013.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Hoyo C. Layered double hydroxides and human health: an overview. Appl Clay Sci. 2007;36:103–121. doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2006.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demel J, Pleštil J, Bezdička P, Janda P, Klementová M, Lang K. Layered zinc hydroxide salts: delamination, preferred orientation of hydroxide lamellae, and formation of ZnO nanodiscs. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;360:532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djaballah R, Bentouami A, Benhamou A, Boury B, Elandaloussi EH. The use of Zn-Ti layered double hydroxide interlayer spacing property for low-loading drug and low-dose therapy. Synthesis, characterization and release kinetics study. J Alloy Compd. 2018;739:559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.12.299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco-marquez M, Aguilar-fernández M, Galano A. Anthranilic acid as a secondary antioxidant: implications to the inhibition of Å OH production and the associated oxidative stress. Comput Theor Chem. 2016;1077:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.comptc.2015.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser MS. Inorganic layered double hydroxides as ascorbic acid (vitamin C) delivery system—intercalation and their controlled release properties. Collides Surf B Biointerfaces. 2009;73:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Lei L, O’Hare D, Xie J, Gao P, Chang T. Intercalation and controlled release properties of vitamin C intercalated layered double hydroxide. J Solid State Chem. 2013;203:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jssc.2013.04.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SH, Han YS, Choy JH. Intercalation of functional organic molecules with pharmaceutical, cosmeceutical and nutraceutical functions into layered double hydroxides and zinc basic salts. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2001;22(9):1019–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Khan AI, Ragavan A, Fong B, Markland C, O’Brien M, Dunbar TG, Williams GR, O’Hare D. Recent developments in the use of layered double hydroxides as host materials for the storage and triggered release of functional anions. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2009;48:10196–10205. doi: 10.1021/ie9012612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kondjoyan A, Portanguen S, Duchène C, Mirade PS, Gandemer G. Predicting the loss of vitamins B3 (Niacin) and B6 (pyridoxamine) in beef during cooking. J Food Eng. 2018;3:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mougin K, Bruntz A, Severin D, Teleki A. Morphological stability of microencapsulated vitamin formulations by AFM imaging. Food Struct. 2016;9:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.foostr.2016.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto K. Infrared and Raman spectra of inorganic and coordination compounds. New York: Wiley; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Rajamathi M, Kamath PV. Anionic clay-like behaviour of α-nickel hydroxide: chromate sorption studies. Mater Lett. 2003;57:2390–2394. doi: 10.1016/S0167-577X(02)01240-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas R, Palena MC, Jimenez-Kairuz AF, Manzo RH, Giacomelli CE. Modeling drug release from a layered double hydroxide-ibuprofen complex. Appl Clay Sci. 2012;62–63:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2012.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silion M, Hritcu D, Lisa G, Popa MI. New hybrid materials based on layered double hydroxides and antioxidant compounds. Preparation, characterization and release kinetic studies. J Porous Mater. 2012;19:267–276. doi: 10.1007/s10934-011-9473-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava M, Singh NP, Yadav RA. Experimental Raman and IR spectral and theoretical studies of vibrational spectrum and molecular structure of Pantothenic acid (vitamin B5) Spectrochim Acta Part A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2014;129:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2014.02.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stählin W, Oswald HR. The topotatic reaction of zinc hydroxide nitrate with aqueous metal chloride solutions. J Solid State Chem. 1971;3:256–264. doi: 10.1016/0022-4596(71)90038-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaraganesan N, Joshua BD. Vibrational spectra and fundamental structural assignments from HF and DFT calculations of methyl benzoate. Spectrochim Acta Part A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2007;68:771–777. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2006.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tylewicz U, Inchingolo R, Rodriguez-Estrada MT. Nutraceutical and functional food components. Netherlands: Elsevier Inc.; 2017. Food aroma compounds; pp. 297–334 . [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez-Carriles CA, Carbajal-Arizaga GG, Silva-Jara JM, Reyes-Becerril MC, Aguilar-Uscanga BR, Macías-Rodríguez ME. Chemical and biological protection of food grade nisin through their partial intercalation in laminar hydroxide salts. J Food Sci Technol. 2020;57:3252–3258. doi: 10.1007/s13197-020-04356-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W, Hewson L, Linforth R, Taylor M, Fisk ID. Effects of aroma and taste, independently or in combination, on appetite sensation and subsequent food intake. Appetite. 2017;114:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Liu X, Tian W, Yan D, Sun X, Lei X. Adsolubilization of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol from aqueous solution by surfactant intercalated ZnAl layered double hydroxides. Chem Eng J. 2015;279:597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2015.05.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.