Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate sensory characteristics in radishes, processed through different methods, using chemosensory-assisted instruments. For electronic tongue (E-tongue) analysis, freeze-dried radish was high in the sensor values of sourness, umami, and sweetness, however, the saltiness was the lowest. In particular, the sensor values of taste freeze-dried radish have changed more than that of thermally processed radishes. Unlike the results of E-tongue, volatiles of freeze-dried radish have changed less than that of thermally processed radishes. In detail, amounts of sulfur-containing compound (thiophene) in freeze-dried radish were relatively higher than thermally processed radishes by an electronic nose. For gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and GC-olfactometry, the amount of sulfur-containing compounds in freeze-dried radish were also relatively higher than thermally processed radishes, and odor active compounds were also high in freeze-dried radish.

Keywords: Wintering radish, E-tongue, E-nose, GC-MSD, GC-olfactometry

Introduction

Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) is one of the Brassicaceae crops and is widely used in Korea as well as worldwide. Most of the Domestic production of radishes has been producing on Jeju island, and radishes produced in Jeju island were classified as spring radish, summer radish, autumn radish, and winter radish cultivars according to the sowing season and harvesting time (Boo et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2018a). The sowing season and harvesting time were conducted all year round, and the winter radish cultivar has been cultivated from late September to early October. Radish, which belongs to the root of vegetables, can be used of all parts, such as leaf and root in radish, and it is considered as the main ingredient in radish-based Kimchi (Kim et al., 2018a). Radish contained various glucosinolates (GLS), and thus, it had high nutritional characteristics and effects ( Boo et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2018a, 2019).

GLS, which is contained in radish, is comprised of glucose backbone with sulfur (S) and nitrogen (N), and the damage of vegetables and/or enzyme (myrosinase) action can generate from GLS to sulfur-containing compounds, such as isothiocyanates and sulfides (Boo et al., 2020; Dinkova-Kostova and Rumen, 2012). Isothiocyanates had sensory characteristics in vegetables, as well as physiological effects. Among the isothiocyanates, sulforaphane had the anticancer effect and erucin had the antioxidant effects (Clarke et al., 2011; Dinkova-Kostova and Rumen, 2012). Sulfides are associated with radish scents and taste components, and off-odors can be shown in vegetables according to the concentrations of volatile sulfides (Boo et al., 2020).

The concentrations of volatiles and taste components can be increased and/or decreased through different methods of processing (Coogan & Wills, 2002; Hong et al., 2020a; Song et al., 2018). Generally, thermal processing may create by-products (pyrazines and furans) and increase amounts of volatile compounds ( Hong et al., 2020a; Lee et al., 2020), and volatiles, which was originated from the roasting process, may influence new aroma activation, such as roasty, coffee, and peanut odors (Lee et al., 2020). Thus, several studies reported that microwave and oven treatment can occur substantial variations in bioactive compounds, color, antioxidant capacity flavor in foods (Hayat et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2014). In addition, air-frying roasting has also investigated that color, sensory, texture characteristics, and physicochemical properties were different between air-frying treatment and conventional heat treatment (Cao et al., 2020; Teruel et al., 2015). On the other hand, a few studies of processed radish were reported and most of the studies investigated the blanching and freeze-drying in radish (Bae et al., 2012; Park et al., 2018).

E-tongue is used as exploring the chemosensory characteristics of each taste compounds in foods through the non-destructive method, as well as fast and objective methods. However, results of E-tongue can be dissimilar to sensory characteristics through the panel test ( Boo et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020). In recent, a few researchers have conducted E-tongue in order to the identification of differences in taste compounds among foods (Boo et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2019; Hong et al., 2020a). In detail, a previous study performed that dissimilarity of radishes was identified using PCA based on E-tongue result according to the different size, and another previous study performed that f roasted coffee beans, which is processed as several drying methods, were also identified using PCA based on E-tongue (Boo et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2019).

To date, most of the researchers have used GC–MS to be identified volatiles samples (Dong et al., 2019; Hong et al., 2020a; Lee et al., 2020; Xian et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2007). Recently, E-nose has been used in order to be explored the difference among the samples, and the use of electronic sensors has been increased to be investigated analyzing flavor characteristics (Dong et al., 2019; Hong et al., 2020a). Accordingly, our study is to investigate the changes of taste flavor profiles in white radish undergo blanching process, oven, microwave treatment, air-frying, and freeze-drying using E-tongue, E-nose, and GC–MS. In addition, differences of sensory characteristics in each sample were identified using multivariate data analysis.

Materials and methods

Materials

Wintering radishes, produced in Jeju island in 2020, were purchased from a local grocery market (Jinju, Republic of Korea). To prevent the oxidation by steel, radishes slurry were produced using the plastic plate. The slurry (30 g) was produced by blanching (110 °C for 12 min), microwave treatment (800 W for 5 min), oven heating (180 °C for 12 min), air-frying (180 °C for 12 min), and freeze-drying using complexed heat treatment device (EONC200F, SK Magic, Seoul, Korea) and freeze-dryer (Lyoph-Pride 10R, Ilshinbiobase, Yang-ju, Korea), respectively. After each processing, the sensory characteristics of radishes were analyzed (Hayat et al., 2019; Elmassry et al., 2018; Boo et al., 2020).

E-tongue analysis

Taste properties in radishes, which were processed through different methods of processing, were measured using E-tongue (ASTREE II, Alpha M.O.S, Toulouse, France). The sample for E-tongue analysis was made by mixing between radish (30 g) and purified water (100 mL) for 30 min at 400 rpm. The module in E-tongue includes five basic taste sensors, (SRS), saltiness (STS), umami (UMS), sweetness (SWS), and bitterness (BRS), two reference sensors, GPS (metallic) and SPS (spiciness), and a reference electrode (Ag/AgCl) for the calibration. The slurried sample (30 g) was weighed in a 250 mL beaker and extracted by 100 mL of purified water at 50 °C and 300 rpm for 30 min. After the extraction process, the extracted sample was subjected to an E-tongue module, and analysis was repeated six times for each sample. The taste sensor responses in E-tongue were converted to taste scores ranged from 1 to 12 and the general taste distribution was given in a descriptive manner (Lee et al., 2020).

E-nose analysis

Volatile compounds in radishes, which were processed through different methods of processing, were measured using E-nose (HERACLES Neo, Alpha MOS, Toulouse, France). The slurried sampled (1.3 g) was weighed in a headspace vial (22.5 × 75 mm, PTFE/silicone septum, aluminum cap), and the headspace in the vial was collected while stirring (500 rpm) at 50 °C for 20 min by the incubator in E-nose. After the status of headspace in the vial, volatile compounds (1000 µL) were collected by an automatic sampler and into an E-nose. Furthermore, Flame ionization detectors (FID) and MXT-5 column (2 m × 0.18 mm) were used. The flow rate of hydrogen gas was set to 1 mL/ min. The acquisition time of volatiles in a sample was 227 s, trap absorption temperature and trap desorption temperature were 40 °C and 250 °C, respectively. The oven temperature was held at 40 °C for 5 s, increased to 270 °C at a rate of 4 °C/s, and maintained for 30 s. The flow rate of hydrogen (H) gas was set to 1 mL/min. Identification of volatiles was conducted using Kovat’s index library-based AroChembase (Alpha MOS), compounds corresponding to each peak were identified (Hong et al., 2020a; Kim et al., 2018a).

GC–MS coupled with GC–olfactometry (GC-O) analysis

Volatile compounds of radishes, which were processed through different methods of processing, were analyzed by headspace analysis using divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/CAR/PDMS) coated with 50/30 um. The sample (1.3 g) was placed in a headspace vial, sealed with an aluminum cap, and exposed to the headspace of the heated sample at the temperature of 50 °C for 20 min (equilibrium) Volatile compounds which are absorbed by SPME (solid-phase microextraction) fiber, for 25 min (absorption), and the desorption time was 25 min. Volatile compounds in radishes were analyzed using gas chromatography-mass-spectrometry (GC–MS: Agilent 7890A & 5975C, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and HP-5MS column (30 m 0.25 mmi.d. 0.25 um film thickness). For the GC–MS analysis conditions, the oven temperature was at 40 °C for 5 min and then accelerated to 200 °C at a rate of 5 °C/h. The injector temperature was 220 °C, the flow rate of helium (He) was 1.0 mL/min, and the split ratio was 1:10. Separated peaks were analyzed using the totalization chromatogram (TIC) was sympathetic regarding the mass spectrum library (NIST 12) and literature. The amount of volatile compound was calculated by converting the peak area of an internal standard material substance (pentadecane), which was 0.005 ug, and represented as ug/100 g. The retention index (RI) was determined by Eq. (1)

| 1 |

where, RIx is RI of the unknown compound, tRx is retention time of the unknown compound, tRn is retention time of the n-alkane, and tRn + 1 is retention time of the next n-alkane. tRx is between tRn and tRn + 1 (n = number of carbon atoms).

Odor active compounds (OACs) were measured using GC–MS coupled with GC-O (olfactory detection port (ODP) 3, Gerstel Co., Linthicum, MD, USA). Identification of odor active compounds in radish sample was performed 20 min (5–25 min) in order to solvent elution time (5 min) and general detected time of OACs. The intensity of OACs was expressed as four levels ranged from 1 to 4, and higher number indicates higher odor active level. Furthermore, odor description in volatiles was also identified by GC-O (Hong et al., 2020b; Lee et al., 2020).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in duplicates and/or triplicates and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Tukey's multiple range test was used to compare the means by utilizing SAS 9.2 (Statistical Analysis System, Version 9.0, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). P value was determined to be statistically significant (P < 0.05). Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted using XLSTAT software ver. 9.2 (Addinsoft, Paris, France) to identify how the radishes were located in the chemosensory characteristics patterns.

Results and discussion

Analysis of taste compounds using E-tongue

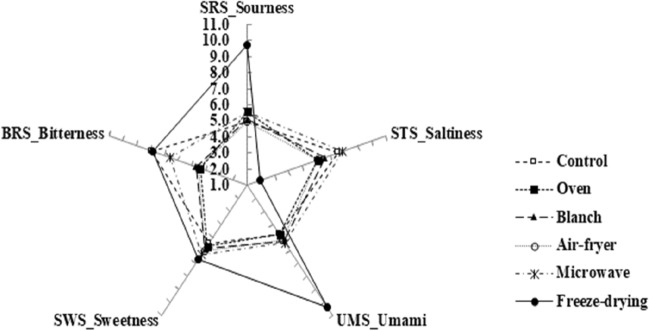

Taste compounds in radishes were measured using E-tongue and the results were shown in Fig. 1. The sensor value of sourness (SRS) has been displayed that freeze-dried radish showed the highest value among all samples. SRS of freeze-dried radish represented a relatively high distinct difference compared to SRS of the other samples. However, there are few differences in SRS among the samples excepted for freeze-dried radish. The results of sensor value of saltiness (STS), freeze-dried radish were the lowest value among all samples, and air-fried radish and microwaved radish showed the increasing tendency of STS compared to raw radish. On the other hand, STS blanched and oven processed radishes did little show difference compared to raw radish. In the case of umami (UMS), the sensor value of freeze-dried radish has been represented that there was a relatively high distinct difference as compared to the other radishes, and the result was in accordance with the results of SRS and STS. Sensor value of bitterness (BRS) has been identified that thermally processed radishes, excepted for freeze-dried radish, showed a decreasing tendency compared to raw radish, and oven precessed, blanched, and air-fried radishes showed relatively high decreased BRS compared to raw radish. Microwaved radish showed relatively low decreased BRS compared to raw radish. On the other hand, BRS of freeze-dried radish has represented a similar to raw radish. Previous study (Boo et al., 2020) demonstrated the taste pattern in different sized wintering radish samples using electronic tongue. Electronic tongue system distinguished variation of each taste pattern in wintering radish samples. Big-sized radished showed higher bitterness, medium-sized radished showed higher saltiness, and small-sized radished showed higher sourness and sweetness compared to others. Literature for the electronic tongue system in food studies include the sensory properties of seasonings reported by Dong et al. (2017), and Jeon et al. (2017) noted variety identification of ginseng using electronic tongue. In this study, it is determined that taste intensity of Jeju wintering radish can be used as a basic database in the food industry using radish through electronic sensor analyses. In addition, standard results presentation by electronic tongue sensors can be utilized as comparison results in various radish varieties.

Fig. 1.

Taste intensities of the thermal processed wintering radish samples using E-tongue

Multivariate analysis of taste compounds in raw radish and processed radishes

Multivariate analysis (PCA and CA) was performed on the E-tongue dataset to distinguish radishes through the different methods of processing, and the separated patterns in radishes have been identified via multivariate analysis (Fig. 2A, B). Besides, differences in taste compounds among all radishes were identified using PCA biplot. Principal components 1 (PC1) has displayed 76.24% variance, and PC2 has displayed 16.62% variance. Thus, a total of PCs have displayed 92.86% variances. Overall, radishes have been mostly separated from the axis of PC1 according to differences in processing. All processed radishes, which were processed through thermal processing, have been located on the negative axis of PC1, however, freeze-dried radish was located on the positive axis of PC1. Freeze-dried radish has been separated by SRS and UMS, and thus it is located on the 1st quadrant, and it was identified that SRS and UMS were the highest value among all samples (Fig. 1). Raw radish and microwaved radish have been located on the 2nd quadrant, and raw radish has been located near microwaved. Besides, raw and microwaved radishes were separated by STS, which means the main variable in raw and microwaved radishes was identified as STS. Blanched, oven processed, and air-fried radishes have been separated by the axis of PC2, thus these radishes have been located on the negative axis of PC2. Unlike freeze-dried, microwaved, and raw radishes, blanched, oven processed, and air-fried radishes have been identified that these samples did not influence by a certain specific variable, which may be considered that biplot results of these radishes were separated by complex taste components. Blanched, oven processed, and air-fried radishes were located closely, and the results of five taste compounds were similar to those among these radishes (Fig. 1). Among all radishes, the dissimilarity was explored using CA, and three separated clusters were identified (Fig. 2B). Freeze-dried radish was identified as cluster I, and oven processed, blanched, and air-fried radishes were identified as cluster II. Raw radish and microwaved radish were identified as cluster III.

Fig. 2.

Interrelation of between each taste and thermal processed wintering radish samples using PCA analysis (A), cluster analysis of taste pattern in thermal processed wintering radish samples using E-tongue (B), interrelation of between each taste and thermal processed wintering radish samples using PCA analysis (C), cluster analysis of odor pattern in thermal processed wintering radish samples using E-nose (D), interrelation of between each odor and thermal processed wintering radish samples using PCA analysis (E) and cluster analysis of OACs pattern (F) in thermal processed wintering radish samples using GC-O

In this study, taste intensity patterns confirmed that relatively higher changes of taste compounds occurred by freeze-drying than thermal processing, and between the microwaved and raw radishes, these radishes showed a relatively lower dissimilarity compared to other radishes. These results may be considered that microwave treatment was relatively lower changes of taste compounds as compared to other processing.

Analysis of volatile compounds using E-nose

Volatile compounds were detected using E-nose, and a total of 15 volatile compounds in raw and processed radishes were detected (Table 1). Among all volatiles, thiophene was the dominant contents of the volatile compound, and this compound had the alliaceous, garlic-like, and sulfurous-like odors, followed by decane, which had odorless characteristics. In the freeze-dried radish, methyl formate showed the dominant content of the volatile compound, which elicits fruity and plum odors. Unlike freeze-dried radish, thermally processed radishes showed relatively decreased contents of methyl formate compared to raw radish.

Table 1.

Volatile compounds in thermally processed wintering radish samples using E-nose analysis (peak area × 103)

| Compounds | RTa(RIb) | Sensory description | Control | Oven | Blanch | Air-fryer | Microwave | Freeze-drying |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methyl formate | 17.37(376) | Fruity, plum | 0.84 ± 0.08 | 0.49 ± 0.02 | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.07 | 3.80 ± 0.54 |

| Methanol | 18.63(396) | Pungent, strong | 0.21 ± 0.08 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.11 | 0.42 ± 0.07 | 1.38 ± 0.45 |

| Propenal | 22.37(456) | Almond, cherry, choking | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.56 ± 0.10 |

| Thiophene | 37.78(654) | Alliaceous, garlic, sulfurous | 61.40 ± 10.27 | 16.45 ± 2.99 | 21.48 ± 4.32 | 15.77 ± 3.70 | 4.12 ± 1.86 | 36.40 ± 4.78 |

| Propanoic acid | 44.89(716) | Pungent, rancid, soy, vinegar | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.04 | 0.04 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.00 |

| Ethyl butyrate | 53.77(801) | Banana, caramelized, sweet | 0.14 ± 0.05 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.03 |

| 2-Butylfuran | 61.71(895) | Fruity, spicy, sweet | 1.37 ± 0.12 | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 0.43 ± 0.04 | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.07 | 0.75 ± 0.16 |

| Decane | 65.25(1,001) | Odorless | 10.89 ± 9.88 | 6.94 ± 3.31 | 6.26 ± 2.31 | 6.20 ± 2.35 | 5.38 ± 1.84 | 0.34 ± 0.05 |

| 1,2-Dichloro-benzene | 67.25(1,052) | Aromatic, pleasant | 1.32 ± 1.26 | 0.89 ± 0.58 | 0.77 ± 0.47 | 0.72 ± 0.33 | 0.62 ± 0.32 | 0.10 ± 0.09 |

| Linalool | 69.45(1,106) | Fresh, fruity, green, spicy, sweet | 0.51 ± 0.42 | 0.33 ± 0.18 | 0.30 ± 0.13 | 0.27 ± 0.06 | 0.23 ± 0.09 | 0.25 ± 0.04 |

| Decanal | 76.03(1,215) | Burnt, fatty, floral, herbaceous | 0.30 ± 0.09 | 0.14 ± 0.05 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.05 |

| 1-Menthen-8-thiol | 80.63(1,301) | Grape, resinous, woody | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.06 |

| γ-Decalactone | 88.71(1,472) | Coconut, fatty, oily | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.36 ± 0.02 |

| 8-Methyl pentadecane | 91.41(1,532) | Odorless | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.24 ± 0.00 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 0.50 ± 0.02 |

| Propyl tetradecanoate | 108.13(1,911) | Odorless | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

aRT: retention time

bRI: retention index

GLS is known as one of the potentially influential factors on the sensory characteristics of radish, and its backbone can be destroyed through the activation of the enzyme (myrosinase) and action of external energy (activation of steel plate). After the action of the enzyme and/or external energy, GLS in radish generally convert to sulfur-containing compounds, and these compounds influence the fragrance of the radish (Blazrvic & Mastelić, 2009; Boo et al., 2020). In this study, thiophene, which is one of the sulfur-containing compounds, was detected as the dominant contents of volatile compounds in radish samples, except for microwaved radish. Thus, thiophene in radish may affect the odor activation of radish as well as taste characteristics of radish (Bae et al., 2012; Boo et al., 2020). A previous study also identified that sulfur-containing compounds influenced the fragrance of red radish, and it was the dominant compound in red radish (Chen et al., 2017). In this study, sulfur-containing compounds in freeze-dried radish had relatively higher than the thermally processed radishes. Accordingly, freeze-drying may be considered as the better method of preserved fragrance in radish. The second dominant volatile compound (decane) was detected that it was the highest amount in raw radish, and it was decreased amount via the processing. Unlike thiophene, decane is one of the hydrocarbons, and these compounds had a higher threshold compared to the other volatiles, such as sulfur-containing compounds, volatile alcohols, volatile aldehydes, and heterocyclics (Boo et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020), and it showed the lowest amount in freeze-dried radish. Besides, hydrocarbons can be converted to other volatiles through processing (Lee et al., 2020), this study also identified that decane showed a decreasing tendency through thermal and non-thermal processing. This result can be considered that decreased amount of hydrocarbon (decane) was associated with the increased amount of sulfur-containing compound (thiophene).

Multivariate analysis of volatile compounds in raw radish and processed radishes

PCA and CA were performed on the E-nose dataset to distinguish radishes through the different methods of processing, and the separated patterns in radishes have been identified via multivariate analysis (Fig. 2C, D). In the PCA, PC1 and PC2 have represented 27.95% variance and 37.03% variance, respectively, and a total PCs have represented 94.98% variances. Overall, thermally processed radishes and non-thermally processed radishes (raw and freeze-dried radish) were separated by the axis of PC2, freeze-dried radish, and the other radishes were separated by the axis of PC1. Raw radish has been separated by linalool, which had fresh, fruit, and sweet-like odors, it was located on the 1st quadrant. Freeze-dried radish has been located on the negative axis of PC1, and it has been separated by 8-methyl pentadecane and propanal. 8-Methyl pentadecane had odorless characteristics and propanal had almond, cherry, and choking-like odors (Table 1). Thermally processed radishes have been separated by propyl tetradecanoate and propanoic acid, and thus, these radishes were located on the negative axis of PC2. Similar to the result of CA based on E-tongue, freeze-dried radish has shown a relatively high dissimilarity compared to the others. Unlike the result of E-tongue, microwaved radish has shown a relatively dissimilarity with heat-treated radish (blanched, oven heated, and air-fried radishes) than raw radish.

E-nose, which is similar to E-tongue, is known as the analysis of sensory characteristics using electronic sensors (Dong et al., 2019). E-nose identified each volatiles using the libraries in E-nose, and the characteristics of E-nose has faster process as well as lower standard deviations compared to GC–MS (Boo et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2019; Hong et al., 2020a; Lee et al., 2020). However, E-nose has a lower identified accuracy of each volatiles compared to GC–MS and therefore it is widely used for volatiles pattern analysis among foods (Boo et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2019).

Analysis of volatile compounds using GC–MS

Volatile compounds were identified using GC–MS and the results have been shown in Table 2. A total of 149 volatile compounds were detected, including 36 volatile sulfur-containing compounds, 35 volatile acids and esters, 14 volatile aldehydes, 20 volatile alcohols, 29 volatile hydrocarbons, 10 volatile heterocyclics, and 4 volatile ketones. Among these volatile compounds, sulfur-containing compounds have been detected in freeze-dried radish (22), followed by raw radish (21). Overall, thermally processed radishes have been identified that the number of sulfur-containing compounds showed a relatively decreasing tendency as compared to raw and freeze-dried radishes. Among thermally processed radishes, microwaved radish showed lowest the number of sulfur-containing compounds (15). Dimethyl disulfide, dimethyl trisulfide, methylthio-acetonitrile, 1-isothiocyanato-4-(methylthiod)buane (erucin), and 1- isothiocyanato -5-(methylthio)pentane (berteroin) were relatively high in sulfur-containing compounds and these volatiles showed relatively decreased contents compared to raw radish through the thermal processing. On the other hand, freeze-dried radish exhibited relatively smaller decreased contents compared to thermally processed radishes, and dimethyl trisulfide, 1-isothiocyanato-4-(methylthio)butane, and 1-isothiodcyanato-5-(methylthio)pentane have shown the increasing tendency compared to raw radish.

Table 2.

Volatile compounds in thermally processed wintering radish samples using GC–MS

| Compounds | RTa (min) | RIb | Contents (ug/100 g) | I.D.c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | Oven | Air-fried | Blanched | Microwave | Freeze drying | ||||

| Sulfur-containing compounds(36) | |||||||||

| Propyl mercaptan | 3.39 | < 800 | ND4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.04 ± 0.06 | MS |

| Ethylene sulfoxide | 3.48 | < 800 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.04 ± 0.05 | MS |

| Dimethyl disulfide | 5.82 | < 800 | 155.48 ± 85.39 | 43.84 ± 13.01 | 32.14 ± 12.84 | 67.90 ± 31.96 | 11.31 ± 7.35 | 73.51 ± 13.95 | MS/RI |

| Methyl sulfocyanate | 6.04 | < 800 | 0.27 ± 0.38 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.27 ± 0.38 | MS |

| Methyl isothiocyanate | 6.17 | < 800 | 0.15 ± 0.21 | ND | 0.04 ± 0.06 | 0.25 ± 0.36 | 0.59 ± 0.83 | 0.09 ± 0.13 | MS |

| N-Ethyl-1,3-dithioisoindoline | 7.62 | < 800 | 3.26 ± 4.61 | ND | ND | ND | 0.02 ± 0.03 | ND | MS |

| Tetrahydro-thiophene | 8.49 | 826 | 2.29 ± 0.64 | 1.87 ± 0.38 | 1.37 ± 0.21 | 3.98 ± 2.60 | 0.58 ± 0.83 | 3.35 ± 0.48 | MS |

| Methyl thiofuran | 10.80 | 893 | 0.98 ± 0.47 | 0.05 ± 0.07 | 0.04 ± 0.05 | 0.26 ± 0.32 | ND | 0.78 ± 0.32 | MS |

| Diallyl sulfide | 10.91 | 896 | ND | 0.04 ± 0.06 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 2-ethylbenzenesulphonamide | 11.45 | 912 | ND | ND | 0.06 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Isothiocyanic acid, butyl ester | 12.78 | 954 | 0.08 ± 0.11 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.10 ± 0.14 | MS |

| 2,3,4-Trithiapentane | 12.86 | 956 | ND | ND | 7.10 ± 3.25 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Dimethyl trisulfide | 13.59 | 977 | 70.82 ± 29.84 | 9.42 ± 1.78 | 7.36 ± 2.57 | 28.42 ± 15.39 | 4.28 ± 2.98 | 110.46 ± 3.48 | MS/RI |

| 3-Butenyl isothiocyanate | 14.42 | 1000 | 1.29 ± 0.38 | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.48 | 2.22 ± 2.06 | ND | 1.40 ± 0.17 | MS |

| 4-Dimethyl-1,3-thiazole | 14.46 | 1001 | ND | ND | ND | 1.14 ± 0.77 | 0.54 ± 0.77 | ND | MS |

| Sulfurous acid, nonyl 2-propyl ester | 17.66 | 1103 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.19 ± 0.27 | MS |

| Pentyl isothiocyanate | 17.99 | 1115 | 0.98 ± 0.34 | 0.22 ± 0.27 | 0.11 ± 0.15 | 0.94 ± 0.71 | ND | 2.78 ± 0.50 | MS |

| Methyl (methylthio)methyl disulfide | 18.84 | 1145 | 0.45 ± 0.64 | 0.19 ± 0.26 | ND | 0.14 ± 0.20 | ND | ND | MS |

| 4-Methylpentyl isothiocyanate | 19.86 | 1179 | 2.65 ± 0.70 | 1.28 ± 0.22 | 0.54 ± 0.62 | 1.14 ± 0.39 | 0.29 ± 0.41 | 3.78 ± 5.35 | MS |

| Tetrahdro-thienylacetonitrile | 20.52 | 1200 | ND | ND | ND | 3.57 ± 1.85 | ND | ND | MS |

| Ethyl isothiocyanate | 20.53 | 1200 | ND | 0.24 ± 0.34 | ND | ND | 0.41 ± 0.13 | ND | MS |

| 1-Cyano-4,5-epithiopentane | 20.60 | 1203 | ND | 2.56 ± 3.24 | 3.06 ± 4.27 | 0.86 ± 1.21 | ND | ND | MS |

| Hexyl isothiocyanate | 20.92 | 1215 | 1.34 ± 1.89 | 1.82 ± 0.20 | 1.15 ± 0.19 | 3.59 ± 2.56 | 0.51 ± 0.36 | 10.32 ± 1.31 | MS |

| 3-Amino-2-thioformylfuran | 21.40 | 1233 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 5.35 ± 7.57 | MS |

| Dimethyl tetrasulfide | 21.44 | 1235 | 1.94 ± 0.18 | 0.385 ± 0.13 | 1.05 ± 0.32 | 1.76 ± 2.49 | 0.78 ± 1.10 | 6.47 ± 0.39 | MS |

| Tetrahydro- 2-thiopheneacetonitrile | 21.56 | 1239 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.34 ± 0.48 | MS |

| Sulfurous acid, 2-propyl tridecyl ester | 23.04 | 1292 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | 0.05 ± 0.06 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | ND | MS |

| 3-Methylthiopropyl isothiocyanate | 23.99 | 1329 | 2.93 ± 0.44 | 1.38 ± 0.29 | 1.06 ± 0.52 | 3.83 ± 2.75 | 0.53 ± 0.37 | 7.64 ± 1.41 | MS |

| Sulfurous acid, 2-propyl tetradecyl ester | 26.25 | 1416 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.05 ± 0.08 | MS |

| Methylthio-acetonitrile | 26.68 | 1434 | 7.80 ± 11.04 | 1.13 ± 1.60 | 1.54 ± 2.02 | 9.76 ± 7.23 | 0.15 ± 0.21 | ND | MS |

| 1-Isothiocyanato-4-(methylthio)butane (erucin) | 27.18 | 1454 | 171.33 ± 23.07 | 78.80 ± 12.22 | 67.96 ± 32.09 | 78.88 ± 33.27 | 31.26 ± 16.91 | 304.27 ± 64.42 | MS |

| Isothiocyanic acid, phenethyl ester | 27.91 | 1483 | 0.88 ± 0.13 | 0.36 ± 0.17 | 0.20 ± 0.28 | 1.55 ± 1.39 | ND | 1.85 ± 0.12 | MS |

| 1-Isothiocyanato-5-(methylthio)pentane (berteroin) | 29.79 | 1563 | 5.39 ± 0.78 | 0.90 ± 1.27 | 1.14 ± 1.61 | 1.45 ± 2.05 | 0.10 ± 0.14 | 7.61 ± 1.78 | MS |

| Sulfurous acid, octadecyl 2-propyl ester | 31.39 | 1632 | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Sulfurous acid, butyl heptadecyl ester | 32.98 | > 1700 | 0.07 ± 0.06 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Sulfurous acid, butyl dodecyl ester | 33.20 | > 1700 | ND | ND | ND | 0.07 ± 0.10 | ND | ND | MS |

| Acids and esters (35) | |||||||||

| 3-Bromo-2-naphthoic acid | 2.12 | < 800 | ND | ND | ND | 0.02 ± 0.03 | ND | ND | MS |

| Dibutyl tartrate | 3.51 | < 800 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.07 ± 0.10 | MS |

| Ethyl 6-isocyanatohexanoate | 8.46 | 825 | ND | ND | ND | 0.11 ± 0.16 | ND | ND | MS |

| 9-Octadecenoic acid | 10.26 | 878 | ND | ND | ND | 0.07 ± 0.04 | ND | ND | MS |

| Octyl 3-phenylpropanoate | 11.52 | 914 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.01 | ND | MS |

| Pentafluoropropionic acid, nonyl ester | 16.74 | 1075 | ND | ND | 0.06 ± 0.08 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 2-Bromopropionic acid, 6-ethyl-3-octyl ester | 17.24 | 1090 | ND | 0.01 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Decyl bromoacetate | 17.27 | 1091 | ND | 0.01 ± 0.01 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Octanoic acid, methyl ester | 18.70 | 1140 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.54 ± 0.18 | MS |

| Geranyl acetate | 18.98 | 1149 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.24 ± 0.34 | MS |

| Ethyl octanoate | 20.78 | 1210 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.93 ± 1.32 | MS/RI |

| Fumaric acid, 3-hexyl tridecyl ester | 22.06 | 1257 | ND | 0.01 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Phenethyl acetate | 22.48 | 1272 | ND | ND | 0.08 ± 0.12 | ND | ND | ND | MS/RI |

| 2-Phenylethyl 4-cyanobenzoate | 22.48 | 1273 | 0.07 ± 0.10 | 0.12 ± 0.17 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Glutaric acid, 2-methylbenzyl octadecyl ester | 22.48 | 1273 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.11 ± 0.15 | MS |

| Hexanoic acid, 2-propenyl ester | 22.53 | 1274 | ND | 0.04 ± 0.06 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 9-Methyldecanoic acid | 25.19 | 1375 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Isobutyl isobutyrate | 25.57 | 1389 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.70 ± 0.27 | MS |

| Ethyl decanoate | 26.01 | 1406 | 0.11 ± 0.06 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | ND | 0.40 ± 0.20 | MS/RI |

| Ethyl pentadecanoate | 30.71 | 1601 | 0.03 ± 0.05 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Phthalic acid, ditridecyl ester | 30.79 | 1605 | ND | ND | 0.02 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Phthalic acid, 2-fluorobenzyl ethyl ester | 30.83 | 1606 | ND | ND | 0.02 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Tridecyl methoxyacetate | 30.91 | 1610 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Oxalic acid, 6-ethyloct-3-yl heptyl ester | 31.40 | 1632 | ND | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.01 | ND | ND | MS |

| 2-Ethoxyethenyl acetate | 31.80 | 1650 | ND | 0.01 ± 0.01 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Decanedioic acid, didecyl ester | 32.22 | 1668 | ND | 0.03 ± 0.01 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Oxalic acid, isobutyl tetradecyl ester | 32.78 | 1692 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.03 ± 0.04 | MS |

| Propanoic acid, nonyl ester | 32.89 | 1697 | ND | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | MS |

| Trioctyl phosphate | 33.03 | > 1700 | ND | 0.01 ± 0.01 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Fumaric acid, 2-decyl tridecyl ester | 33.37 | > 1700 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.02 | ND | MS |

| Methyl palmitate | 37.81 | > 1700 | 0.17 ± 0.21 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Methyl triacontanoate | 37.77 | > 1700 | ND | 0.02 ± 0.03 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 37.82 | > 1700 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.20 ± 0.29 | MS |

| Tridecanoic acid, methyl ester | 37.85 | > 1700 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.02 ± 0.00 | MS |

| Hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester | 39.57 | > 1700 | ND | 0.15 ± 0.06 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.61 | 0.07 ± 0.10 | 0.07 ± 0.06 | MS |

| Aldehydes (14) | |||||||||

| Hexanal | 8.46 | 826 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.33 ± 0.47 | ND | MS/RI |

| 2-Hexenal | 10.18 | 876 | 0.64 ± 0.19 | ND | ND | 0.13 ± 0.18 | ND | 0.64 ± 0.19 | MS/RI |

| Benzaldehyde | 13.68 | 980 | ND | 0.52 ± 0.41 | 0.11 ± 0.16 | 0.03 ± 0.04 | 2.25 ± 0.62 | 0.82 ± 0.43 | MS/RI |

| Octanal | 15.01 | 1020 | ND | 0.56 ± 0.12 | ND | 0.35 ± 0.49 | 0.27 ± 0.39 | 0.97 ± 0.06 | MS/RI |

| 2,4-Heptadienal | 15.26 | 1028 | ND | ND | ND | 0.60 ± 0.35 | 0.20 ± 0.28 | ND | MS/RI |

| Benzeneacetaldehyde | 16.33 | 1062 | ND | 0.07 ± 0.09 | ND | 0.25 ± 0.17 | 0.46 ± 0.27 | 1.18 ± 0.55 | MS |

| 2-Octenal | 16.73 | 1075 | ND | ND | ND | 0.85 ± 0.53 | ND | ND | MS/RI |

| Nonanal | 18.10 | 1119 | 1.52 ± 0.16 | 2.74 ± 0.77 | 1.55 ± 0.64 | 3.08 ± 1.68 | 1.05 ± 0.87 | 10.79 ± 0.88 | MS/RI |

| 2-Nonenal | 19.74 | 1175 | ND | ND | ND | 0.07 ± 0.10 | ND | 0.42 ± 0.03 | MS/RI |

| 4-Ethylbenzaldehyde | 20.37 | 1195 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.05 ± 0.07 | ND | MS |

| Decanal | 21.02 | 1219 | 1.95 ± 0.27 | 1.24 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.52 | 1.05 ± 1.48 | 0.49 ± 0.41 | 1.37 ± 0.19 | MS/RI |

| Dodecanal | 22.99 | 1290 | 0.05 ± 0.08 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Tridecanal | 26.36 | 1421 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.11 | 0.11 ± 0.16 | ND | 0.21 ± 0.01 | MS |

| 7-Hexadecenal | 31.12 | 1619 | ND | 0.05 ± 0.01 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Alcohols (20) | |||||||||

| p-Xylol | 10.67 | 889 | 0.05 ± 0.07 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Methyl phenyl oxime | 11.77 | 916 | 0.20 ± 0.28 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Thiacyclohexan-3-ol | 15.22 | 1007 | 0.39 ± 0.55 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 2-Ethyl-1-hexanol | 15.82 | 1046 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.68 ± 0.16 | MS |

| 1-Octanol | 17.08 | 1085 | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 0.49 ± 0.14 | ND | 0.25 ± 0.35 | ND | ND | MS/RI |

| Decanol | 17.10 | 1086 | ND | ND | 0.22 ± 0.17 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 2-Butyloctanol | 18.00 | 1115 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.06 ± 0.08 | ND | MS |

| Benzeneethanol | 18.42 | 1130 | 0.43 ± 0.61 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Phenethyl alcohol | 18.43 | 1131 | 0.10 ± 0.14 | 0.10 ± 0.14 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 1-Nonanol | 20.05 | 1185 | ND | 0.23 ± 0.32 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS/RI |

| Decanol | 20.06 | 1185 | 0.09 ± 0.13 | ND | ND | 0.16 ± 0.22 | ND | ND | MS |

| 2-Propyl-1-heptanol | 26.09 | 1410 | ND | 0.04 ± 0.00 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 9-Octadecen-1-ol | 26.39 | 1422 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.12 ± 0.17 | MS |

| 9-Borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-9-ol | 26.39 | 1422 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.08 ± 0.12 | ND | MS |

| Butylated hydroxytoluene | 28.96 | 1527 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 3.46 ± 4.89 | MS |

| Phytol | 30.87 | 1608 | ND | 0.06 ± 0.09 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 2,5-Dimethylcyclohexanol | 30.98 | 1613 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.11 ± 0.16 | MS |

| Dodecanol | 32.07 | 1661 | ND | 0.03 ± 0.01 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 2,2,4-Trimethyl-1-pentanol | 32.68 | 1688 | ND | 0.28 ± 0.40 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 2-Hexyl-1-decanol | 32.90 | > 1700 | ND | 0.07 ± 0.06 | ND | ND | ND | 0.04 ± 0.06 | MS |

| Hydrocarbons (29) | |||||||||

| Ethenylbenzene | 11.39 | 910 | 0.63 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.37 | ND | 0.18 ± 0.09 | MS |

| 2,2-Dimethylcyclobutyl methylamin | 11.73 | 921 | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | ND | ND | MS |

| 1,2,4-Trimethylbenzene | 14.77 | 1012 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.07 ± 0.10 | ND | MS |

| 1,2,3-Trimethylbenzene | 15.66 | 1041 | ND | ND | 0.09 ± 0.12 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 1,3,5-Trimethylbenzene | 15.68 | 1042 | ND | ND | ND | 0.17 ± 0.25 | ND | ND | MS |

| D-Limonene | 15.83 | 1047 | 0.69 ± 0.46 | 0.19 ± 0.27 | 0.45 ± 0.64 | 0.62 ± 0.37 | 0.11 ± 0.16 | ND | MS/RI |

| 2,5,6-Trimethyl-octane | 15.87 | 1048 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.15 ± 0.22 | MS |

| 2,3,5-Trimethyl-decane | 16.01 | 1052 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.68 ± 0.96 | MS |

| 3-Methyltridecane | 16.89 | 1080 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.68 ± 0.29 | MS |

| 9-Methyl-1-undecene | 16.73 | 1075 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.09 ± 0.07 | MS |

| Pentylcyclopropane | 17.09 | 1086 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.83 ± 0.17 | MS |

| Cyclooctane | 17.12 | 1087 | ND | ND | ND | 0.66 ± 0.93 | ND | ND | MS |

| 5-Ethyl-2,2,3-trimethylheptane | 17.31 | 1092 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.33 ± 0.46 | MS |

| 2,3,4-Trimethylhexane | 17.52 | 1098 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.08 ± 0.11 | MS |

| 1-Phenyl-2-butene | 17.56 | 1099 | ND | ND | 0.02 ± 0.03 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Undecane | 17.58 | 1100 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.12 ± 0.17 | MS/RI |

| 1-Octadecene | 18.50 | 1133 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.36 ± 0.51 | MS |

| Camphor | 19.43 | 1165 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.02 ± 0.03 | MS/RI |

| 3-Tetradecene | 19.73 | 1175 | 0.05 ± 0.07 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Cycloheptane | 20.10 | 1187 | 0.03 ± 0.05 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 3-Ethyl-5-(2'-ethylbutyl)octadecane | 23.03 | 1292 | ND | 0.04 ± 0.00 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| trans-Anethole | 23.11 | 1294 | 0.14 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.06 | 0.14 ± 0.16 | ND | 0.33 ± 0.08 | MS |

| Nonacosane | 31.49 | 1636 | 0.13 ± 0.18 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 3,5-Dimethyloctatriacontane | 31.79 | 1649 | ND | 0.01 ± 0.01 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 5-Ethyl-5-methylnonadecane | 32.12 | 1664 | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.01 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Octacosane | 32.17 | 1666 | ND | 0.07 ± 0.01 | ND | 0.03 ± 0.04 | ND | ND | MS |

| Squalane | 32.98 | > 1700 | ND | ND | 0.06 ± 0.05 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 2,6,10-Trimethylpentadecane | 33.00 | > 1700 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.06 ± 0.09 | MS |

| Tetratetracontane | 33.08 | > 1700 | ND | ND | ND | 0.11 ± 0.15 | ND | ND | MS |

| Heterocyclics (10) | |||||||||

| 2-Pentylfuran | 14.66 | 1008 | 1.25 ± 0.08 | ND | ND | 1.14 ± 0.77 | ND | 1.25 ± 0.08 | MS/RI |

| 4-Hydroxy-3-nitrocoumarin | 16.33 | 1062 | 0.06 ± 0.09 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 3-Dihydro isobenzofuran | 16.33 | 1062 | ND | ND | 0.13 ± 0.18 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 6-Chloro-2,3-dimethyl-4-phenylquinoline | 18.36 | 1128 | ND | 0.06 ± 0.09 | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| Auramine | 18.36 | 1128 | ND | ND | 0.03 ± 0.04 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 3,6-Dianhydro-α-D-glucopyranose | 21.13 | 1223 | ND | ND | ND | 0.07 ± 0.10 | ND | ND | MS |

| 1-Isopropoxy-2-methoxycarbonyl-1-aza-cyclopropane | 26.85 | 1441 | 0.04 ± 0.06 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 6,8-Dimethoxy-4-methyl-4H-chromene | 28.88 | 1524 | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.01 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 1,8-Cineole | 32.24 | 1669 | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| 3,5-Diethylidene-l-xylose | 33.10 | > 1700 | ND | ND | ND | 0.06 ± 0.08 | ND | ND | MS |

| Ketones (4) | |||||||||

| 5-Phenyl-2-pentanone | 22.47 | 1272 | 0.36 ± 0.51 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | MS |

| trans-Geranylacetone | 27.46 | 1431 | ND | ND | ND | 0.36 ± 0.50 | ND | ND | MS |

| 6,10-Dimethyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one | 27.48 | 1466 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.31 ± 0.44 | ND | MS |

| Diphenylmethanone | 31.67 | 1644 | ND | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | ND | ND | ND | MS |

aRT: retention time

bRI: retention index

cI.D.: identification

dND: not detected

Sulfur-containing compounds are known as the dominant volatiles in radish and these volatile compounds were derived from GLS (Blažević & Mastelić, 2009). GLS involve in several metabolisms, such as the generation of sulfur and nitrogen associated with antioxidant and antibacterial. In general, sulfur-containing compounds (isothiocyanates, sulfides, thiocyanates, etc.) are decomposed from GLS by the action of myrosinase as well as thermal processing, fermented processing, cutting, and chewing (Blažević & Mastelić, 2009). In addition, a previous study indicated that GLS in red cabbage has been also decomposed by thermal processing. (Oerlemans et al., 2006). Volatile isothiocyanates and sulfides, which were generated by above a series of processes, can directly influence characteristics of radish flavor as well as physiological functions in vivo (Boo et al., 2020; Clarke et al., 2011; Dinkova-Kostova & Rumen, 2012). For instance, 1-isothiocyanato-4-(methylthio)butane, which is called erucin, contains physiological functions, such as anti-obesity, anti-oxidant, and anti-bacterial effects. Furthermore, it can convert to sulforaphane, which contains a highly anti-tumor effect, through the absorption in the body (Clarke et al., 2011; Dinkova-Kostova & Rumen, 2012). Erucin is derived from Loosen rearrangement of an unstable thiohydroximate intermediate which originates from the decomposition of glucoerucin in radish root (Blažević & Mastelić, 2009). 1- Isothiocyanato -5-(methylthio)pentane (berteroin) is known as sulforaphane analog and this compound has been contained in cabbage, radish root, and rocket salad (Boo et al., 2020; Jung et al., 2014). The effect of berteroin has been identified that this compound had high effective as the depression of skin inflammation (Jung et al., 2014). In the present study, dimethyl disulfide and dimethyl trisulfide, which were associated with off-odors in radish root, showed the decreasing trends undergo thermal processing, however, freeze-dried radish has shown less change of contents compared to thermally processed radishes. Thus, the contents of two volatile sulfides (dimethyl disulfide, dimethyl trisulfide) have been decreased according to thermal degradation, and this phenomenon can affect the fragrance and taste in radish roots, such as the occurrence of off-odors and changes of unique taste in radish root (Boo et al., 2020; Oelemans et al., 2006). According to our findings, the freeze-drying process can influence low changes of volatiles in radish root. In this study, GC–MS and E-nose were not perfectly matched each other, however, sulfur-containing compounds in radish were identified as the dominant volatile compounds, and these compounds showed a decreasing tendency to undergo thermal processing. In addition, sulfur-containing compounds in freeze-dried radish showed a relatively lower decrease compared to thermally processed radishes. It is known that the differences in volatile profiles in the E-nose and GC–MS are associated with the differences in the adsorption method and analysis method (Boo et al., 2020).

In the case of the volatile classes in radish except for sulfur-containing compounds, the contents of volatile aldehydes were only changed according to the different methods of processes. On the other hand, acids and esters, heterocyclics, ketones, alcohols, and hydrocarbons were rarely changed. Among the class of aldehydes, straight-chain aldehydes were high in radishes, such as hexanal, octanal, nonanal, decanal, and dodecanal, and nonanal was dominant concentrations among volatile aldehydes. Straight-chain aldehydes generally had undesirable notes, such as fat and grass-like odors, and these volatile compounds are mainly generated by auto-oxidation of lipid (Bu et al., 2013; Song et al., 2018). Nonanal is also generated by auto-oxidation of lipid. In detail, nonanal is mainly generated by oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids which is known as one of the important fatty acids in foods, and this compound showed the grass-like note (Bu et al., 2013). Previous research indicated that oven drying and freeze-drying processes brought about the increased contents of nonanal (Torres et al., 2010). The present study also identified that nonanal has relatively increased contents compared to raw radish after the oven treatment and freeze-dried processing as well as microwave, blanching, and air-frying treatment. In particular, nonanal in freeze-dried radish was mostly influenced by oxidation of oleic acid (Bu et al., 2013; Torres et al., 2010).

Excepted for sulfur-containing compounds and volatile aldehydes, the rest of the volatiles did not occur any major changes between non-processed radish and processed radishes in this study. Generally, Maillard reaction occurs in the decomposition of sugars, fats, and proteins through thermal processing, and thus furans, pyrazines, and pyrroles are generated (Lee et al., 2020). The previous studies identified that the roasting process, which is over 180 °C, has generated the Maillard reaction by-products (new volatiles), and fatty acids oxidation, which is associated with newly created volatiles, were observed subsequent to oven and microwave heating treatment (Hayat et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2020). On the other hand, Maillard reaction and Maillard reaction by-products have been rarely generated in this study. Accordingly, this phenomenon may be associated with the general composition of radish root, which is known as contained 90% concentration of moisture (Kim et al., 2018b).

Analysis of volatile compounds using GC-O

Odor active compounds (OACs) were detected using GC-O and the results have been shown in Table 3. Among all radishes, OACs were only detected as sulfur-containing compounds, such as sulfides and isothiocyanates. The highest contents of OACs in radishes were identified as dimethyl disulfide and dimethyl trisulfide, which elicit the radish notes, and these volatiles had decreasing trend after thermal processing. On the other hand, freeze-dried radish has equally shown odor intensity (2) as raw radish. Methyl (methylthio)dimethyl disulfide has been only shown as odor activation in raw radish, however, this compound has been not shown in all processed radishes. 4-Methyl pentyl isothiocyanate, hexyl isothiocyanate elicit the cucumber-like and spicy odors, respectively, and these volatiles also represented the trends of decrease in thermally processed radishes. In addition, odor activation of volatile isothiocyanates fewer trends of decrease compared to thermally processed radishes. In the microwaved radish, hexyl isothiocyanate showed the lowest odor intensity (1) among all radishes.

Table 3.

GC-O analysis of odor active compounds (OACs) in thermally processed wintering radish samples

| Odor active compounds | RTa (min) | RIb | Odor intensity | Odor description | I.D.c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | Oven | Air-fried | Blanched | Microwave | Freeze drying | |||||

| Dimethyl disulfide | 5.82 | < 800 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Radish | MS/RI |

| 2,3,4-Trithiapentane | 12.86 | 956 | ND4 | ND | 1 | ND | ND | ND | Radish | MS |

| Dimethyl trisulfide | 13.59 | 977 | 2 | 1 | ND | 1 | ND | 2 | Radish | MS/RI |

| Methyl (methylthio)methyl disulfide | 18.84 | 1145 | 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Radish, cucumber | MS |

| 4-Methylpentyl isothiocyanate | 19.86 | 1179 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Cucumber | MS |

| Hexyl isothiocyanate | 20.92 | 1215 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Spicy | MS |

| Dimethyl tetrasulfide | 21.44 | 1235 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Radish | MS/RI |

aRT: retention time

bRI: retention index

cI.D.: identification

dND: not detected

Dimethyl sulfide and dimethyl trisulfide are driven from the decomposition of GLS, such as activation of myrosinase and thermal breakdown. Besides, these volatile compounds have been found in radish root and these volatiles can affect the odor activation of radish root (Blažević & Mastelić, 2009; Boo et al., 2020; Oerlemans et al., 2006). In GC–MS analysis, dimethyl sulfide and dimethyl trisulfide were high in all radishes (Table 3), these compounds were identified that responsible for radish root odors by GC-O. Dimethyl sulfide and dimethyl trisulfide have a low threshold, these compounds can appear off-odor activation at a high concentration. Dimethyl disulfide and dimethyl trisulfide were generated by bacterial degradation and oxidation of methanethiol as well as degradation of GLS (Li et al., 2013). Previous studies identified that the high concentrations of dimethyl disulfide and dimethyl trisulfide were found in radish-based Kimchi by GC–MS (Kim et al., 2018a), and dimethyl disulfide and dimethyl trisulfide were responsible for radish root odors by GC-O (Boo et al., 2020). Methyl (methylthio)methyl disulfide and dimethyl tetrasulfide elicit the earth-like and white radish odors by GC-O, respectively (Boo et al., 2020), these compounds also detected in our results of volatiles by GC-O. 2,3,4-Trithiapentane is considered as sulfur-containing volatiles, which is associated with off-odor (Ruotai et al., 2007), this volatile compound was also found in air-fired radish (Table 3). 4-Mehtylpentyl isothiocyanate is one of the volatiles, which was only found in white radish and black radish (Blažević & Mastelić, 2009). A previous study reported that 4-(methylthio)-3-butenyl isothiocyanate and 4-(methylthio)butyl isothiocyanate were found in the radish root, which were generated by 4-(methylthio)-3-butenyl GLS and 4-(methylthio)butyl GLS, respectively (Blažević & Mastelić, 2009). Similar to the previous metabolism, generation of 4-methylpentyl isothiocyanate may be influenced by decomposition of 4-methylpentyl GLS. Hexyl isothiocyanate is mainly discovered in the radish seed and it contains a dominant concentration (18.7%) in radish seed (Afsharypuor et al., 2005). However, this compound was identified as low concentration compared to radish seed, this result may be associated with the difference in parts of radish volatiles and/or changes in the growth of radish volatiles. Although OACs have low amounts without dimethyl disulfide and dimethyl trisulfide, these OACs had odor descriptions associated with radish odors by GC-O, because of low threshold characteristics (Li et al., 2013).

Volatile compounds determied by GC/MS and GC-O showed the similar results compared to that of e-nose. Non-thermallized samples (control and freezing-drying) had more plenty of volatiles than these of thermall sample sets. Sulfur-containing compounds, major volatiles in all samples, had low boiling points and thermall processing vaporized and eleminated these compounds from samples. Neverthless, taste intensity did not observed thermall processing. Anhydrous condition, freezing-drying, showed stronger intensity in the radish sample compared to others.

Multivariate analysis of OACs in raw radish and processed radishes

PCA and CA were performed on the OACs dataset to distinguish radishes through the different methods of processing, and the separated patterns in radishes have been identified using multivariate analysis (Fig. 2E, F). In the PCA, PC1 has shown 54.6% variance and PC2 has shown 80.18% variance. Most of the samples were separated by the axis of PC1, raw radish was located near freeze-dried radish. Thermally processed radishes were located on the negative axis of PC1 without blanched radish. On the other hand, thermally processed radishes were located on the positive axis of PC2 without microwaved radish. Thus, different methods of processing can influence odor activation in radish roots. In detail, blanched radish has been separated by hexyl isothiocyanate and dimethyl tetrasulfide, and thus, blanched radish has been located on the 1st quadrant. Oven treated radish and air-fried radish have been separated by 2,3,4-trithiapentane, and thus, these radishes have been located on the 2nd quadrant. Raw radish and freeze-dried radish have been separated by dimethyl disulfide, dimethyl trisulfide, and 4-methylpenthyl isothiocyanate, and thus, these radishes have been located on the 4th quadrant. In the CA, the dissimilarity among raw radish, freeze-dried radish, and thermally processed radishes was identified. The dissimilarity between raw radish and freeze-dried radish represented relatively lower compared to other radishes. Microwaved radish represented relatively higher dissimilarity among thermally processed radishes and this dissimilarity may be influenced by decreased amounts of OACs in microwaved radish. The recent research reported that volatile compounds in radishes and radish-like samples were analyzed by GC–MS with SPME and the results of GC–MS were used for PCA (Kim et al., 2018a). In addition, PCA, which was based on the results of OACs by GC-O, was used for separation and difference in various radishes (Boo et al., 2020). Furthermore, results of volatile patterns have been used in different food samples (coffee beans, etc.) without radish (Dong et al., 2019). Similar to previous studies, volatile patterns have been identified by PCA based on the results of GC-O in this study.

In summary, sensory characteristics (taste and flavor) in radishes, which were produced by different methods of processing, have been analyzed by chemosensory instruments (E-tongue, E-nose, and GC–MS). Among all radishes, freeze-dried radish showed the biggest variations of taste sensory value by E-tongue, however, microwaved radish showed the smallest variations of taste sensory value by E-tongue. In the flavor characteristics, freeze-dried radish showed the biggest variations of volatiles by E-nose. Thermally processed radishes showed a few variations of volatiles. On the other hand, OACs in freeze-dried radish showed fewer variations compared to thermally processed radishes. Accordingly, our results of chemosensory characteristics may provide the basic research data to consumers and/or academic circles.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with the support of “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science and Technology Development (Project No. PJ01496201)”, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Seong Jun Hong, Email: 01028287383a@gmail.com.

Chang Guk Boo, Email: dbs7887@naver.com.

Jookyeong Lee, Email: leejook@deakin.edu.au.

Seong Wook Hur, Email: castleuk123@gmail.com.

Seong Min Jo, Email: jojo9875@naver.com.

Hyangyeon Jeong, Email: giddus9967@naver.com.

Sojeong Yoon, Email: dbsthwjd0126@naver.com.

Youngseung Lee, Email: youngslee@dankook.ac.kr.

Sung-Soo Park, Email: foodpark@jejunu.ac.kr.

Eui-Cheol Shin, Email: eshin@gnu.ac.kr.

References

- Afsharypuor S, Balam MH. Volatile constituents of Raphanus sativus L. var. niger seeds. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 2005;17(4):440–441. doi: 10.1080/10412905.2005.9698955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bae RN, Lee YK, Lee SK. Changes in nutrient levels of aqueous extracts from radish (Raphanus sativus L.) root during liquefaction by heat and non-heat processing. Horticultural Science and Technology. 2012;30(4):409–416. doi: 10.7235/hort.2012.11141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blažević I, Mastelić J. Glucosinolate degradation products and other bound and free volatiles in the leaves and roots of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) Food Chemistry. 2009;113(1):96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.07.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boo CG, Hong SJ, Lee YS, Park SS, Shin EC. Quality characteristics of wintering radishes produced in Jeju island using E-Nose, E-Tongue, and GC-MSD Approach. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition. 2020;49(12):1407–1415. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2020.49.12.1407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bu J, Dai Z, Zhou T, Lu Y, Jiang Q. Chemical composition and flavour characteristics of a liquid extract occurring as waste in crab (Ovalipes punctatus) processing. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2013;93(9):2267–2275. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Wu G, Zhang F, Xu L, Jin Q, Huang J, Wang X. A Comparative study of physicochemical and flavor characteristics of chicken nuggets during air frying and deep frying. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 2020;97(8):901–913. doi: 10.1002/aocs.12376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Karangwa E, Yu J, Xia S, Feng B, Zhang X, Jia C. Characterizing red radish pigment off-odor and aroma-active compounds by sensory evaluation, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry/olfactometry and partial least square regression. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 2017;10(7):1337–1353. doi: 10.1007/s11947-017-1904-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JD, Hsu A, Riedl K, Bella D, Schwartz SJ, Stevens JF, Ho E. Bioavailability and inter-conversion of sulforaphane and erucin in human subjects consuming broccoli sprouts or broccoli supplement in a cross-over study design. Pharmacological Research. 2011;64(5):456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coogan RC, Wills RBH. Effect of drying and salting on the flavour compound of Asian white radish. Food Chemistry. 2002;77:305–307. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00350-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Torres C, Díaz-Maroto MC, Hermosín-Gutiérrez I, Pérez-Coello MS. Effect of freeze-drying and oven-drying on volatiles and phenolics composition of grape skin. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2010;660(1–2):177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova AT, Rumen VK. Glucosinolates and isothiocyanates in health and disease. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2012;18(6):337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H, Moon JY, Lee SH. Discrimination of geographical origins of raw ginseng using the electronic tongue. Korean Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2017;49:349–354. [Google Scholar]

- Dong W, Hu R, Long Y, Li H, Zhang Y, Zhu K, Chu Z. Comparative evaluation of the volatile profiles and taste properties of roasted coffee beans as affected by drying method and detected by electronic nose, electronic tongue, and HS-SPME-GC-MS. Food Chemistry. 2019;272:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmassry MM, Kormod L, Labib RM, Farag MA. Metabolome based volatiles mapping of roasted umbelliferous fruits aroma via HS-SPME GC/MS and peroxide levels analyses. Journal of Chromatography B. 2018;1099:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayat K, Abbas S, Hussain S, Shahzad SA, Tahir MU. Effect of microwave and conventional oven heating on phenolic constituents, fatty acids, minerals and antioxidant potential of fennel seed. Industrial Crops and Products. 140: 111610 (2019)

- Hong SJ, Cho JJ, Boo CG, Youn MY, Lee SM, Shin EC. Comparison of physicochemical and sensory properties of bean sprout and peanut sprout extracts, subsequent to roasting. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition. 2020;49(4):356–369. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2020.49.4.356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SJ, Cho JJ, Boo CG, Youn MY, Pan JH, Kim JK, Shin EC. Inhalation of patchouli (Pogostemon Cablin Benth.) essential oil improved metabolic parameters in obesity-induced Sprague Dawley rats. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):2077. doi: 10.3390/nu12072077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon SY, Kim JS, Kim GC, Choi SY, Kim SB, Kim KM. Analysis of electronic nose and electronic tongue and sensory characteristics of commercial seasonings. Korean Journal of Food Cookery and Science. 2017;33:538–550. doi: 10.9724/kfcs.2017.33.5.538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YJ, Jung JI, Cho HJ, Choi MS, Sung MK, Yu R, Kang YG, Park HY. Berteroin present in cruciferous vegetables exerts potent anti-inflammatory properties in murine macrophages and mouse skin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 15(11):20686-20705 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim MK, Lee MA, Lee KG. Determination of compositional quality and volatile flavor characteristics of radish-based Kimchi suitable for Chinese consumers and its correlation to consumer acceptability. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2018;27(5):1265–1273. doi: 10.1007/s10068-018-0387-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Park JD, Song JM. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of white radish tea by different preparation methods. Culinary Science & Hospitality Research. 2018;24(1):73–81. doi: 10.20878/cshr.2018.24.1.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, Cho YJ, Kim M, Hurh B, Baek HH. Changes in volatile flavor compounds of radish fermented by lactic acid bacteria. Korean Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2019;51:324–329. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Cho JJ, Hong SJ, Kim DS, Boo CG, Shin EC. Platycodon grandiflorum roots: a comprehensive study on odor/aroma and chemical properties during roasting. Journal of Food Biotechnology. 2020;44(9):e13344. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wu J, Li Y, Dai Z. Identification of the aroma compounds in stinky mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi) and comparison of volatiles during fermentation and storage. International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 2013;48(11):2429–2437. [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Geng S, Liu Y, Wang L, Wang H, Zhang J, Chen Y, Yao S. GC-MS analysis of off-odor volatiles from irradiated pork. Nuclear Science and Techniques. 18(1): 30-34 (2007)

- Oerlemans K, Barrett DM, Suades CB, Verkerk R, Dekker M. Thermal degradation of glucosinolates in red cabbage. Food Chemistry. 2006;95(1):19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Park JJ, Park BR, Han GJ, Kim HY. The effect of freezing and thawing conditions on the quality characteristic of blanched radish (Raphanus sativus L.) Food Engineering Progress. 2018;22(1):67–74. doi: 10.13050/foodengprog.2018.22.1.67. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AL, Perry JJ, Marshall JA, Yousef AE, Barringer SA. Oven, microwave, and combination roasting of peanuts: comparison of inactivation of salmonella surrogate Enterococcus faecium, color, volatiles, flavor, and lipid oxidation. Journal of Food Science. 2014;79(8):S1584–S1594. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G, Dai Z, Shen Q, Peng X, Zhang M. Analysis of the changes in volatile compound and fatty acid profiles of fish oil in chemical refining process. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology. 2018;120(2):1700219. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.201700219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teruel MDR, Gordon M, Linares MB, Garrido MD, Ahromrit A, Niranjan K. A comparative study of the characteristics of french fries produced by deep fat frying and air frying. Journal of Food Science. 2015;80(2):E349–E358. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian Z, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Pan Y. Analysis of the volatiles in two kinds of Korea Kimchi by Gas Chromatograph-mass spectrometry with solid phase microextraction. Food and Fermentation Industries. 2009;1:059. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D, Tang J, Ding X. Analysis of volatile components during potherb mustard (Brassica juncea, Coss.) pickle fermentation using SPME-GC-MS. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2007;40(5):439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2005.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]