Abstract

Acquiring an understanding of the mechanisms underlying antimicrobial action is important for overcoming bacterial resistance to antimicrobials. This study evaluated three different methods (antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method, metabolic inhibitors fixed broth dilution method, and metabolic inhibitor fixed agar recovery method) for determining the target site of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by treatments with various antimicrobials (ethanol, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, polymyxin B, thymol, acetic acid, and citrus fruit extract). However, the results indicated only weak relationships between MIC values and mechanisms of antimicrobials known to cause damage or injury. In addition, the results of three measurement methods using metabolic inhibitors were not correlated. These results suggest that measurement methods using metabolic inhibitors alone may not be suitable for determining the target site injured by antimicrobials. Therefore, various measurement methods should be compared and analyzed to determine the damage or injury sites targeted by antimicrobials in pathogenic bacteria. Further studies are needed to compare and analyze the various measurement methods for determining the target site injured by antimicrobials in pathogenic bacteria

Keywords: Escherichia coli O157:H7, Antimicrobials, Metabolic inhibitors, Target injury site, Antibacterial mechanism

Introduction

Hurdle technology is an approach for preparing safe and stable foods by integrating various food preservation methods as microorganisms present in the foods are unable to overcome such as integration. The hurdles mostly used in food preservation are based on controlling the water activity, temperature, redox potential, pH, and the use of preservatives (e.g., nitrate, sorbate) (Leistner, 2000). However, thermal, non-thermal, and chemical preservation methods have been used in combination for centuries around the world without detailed knowledge of the mechanism of action. For example, Jin and Lee (2007) observed that a combination of modified atmosphere packaging and chlorine dioxide reduced the levels of foodborne pathogens in mungbean sprouts without negatively affecting the quality of the sprouts. On the other hand, combination treatment with acetic acid and salt has shown antagonistic effects against E. coli O157:H7 (Bae et al., 2017; Chapman and Ross, 2009). These results indicate that the combined effects are highly dependent on the antimicrobial mechanisms or the sites targeted by the individual preservation methods. Thus, understanding the mechanisms by which individual preservation methods exert their antimicrobial effects is important for selecting effective and appropriate hurdle technologies (Leistner, 2000).

The sites targeted by various agents in pathogenic bacteria have been determined using various measurement methods such as fluorescent probe (dye) uptake (Li et al., 2012; Ojeda-Sana et al., 2013), enzyme activity investigated using chromogenic methods (Miao et al., 2016; Sahalan et al., 2013), leakage of intracellular components (Rurián-Henares and Morales, 2008; Zhang et al., 2016), and morphological changes (Hyun and Lee, 2020; Tan et al., 2017). Among these, methods involving metabolic inhibitors (antibiotics) are commonly used to identify the sites targeted by antimicrobials in pathogenic bacteria. Metabolic inhibitors have been used to investigate the metabolic activities and target sites of injury in pathogenic bacteria subjected to chemical or physical treatments. Broth dilution or agar recovery methods are the most commonly used techniques to measure the sensitization of bacteria to metabolic inhibitors. The broth dilution method uses a liquid medium containing metabolic inhibitors or antimicrobials at diluted concentrations, which are inoculated with microbial cells treated with metabolic inhibitors or antimicrobials (García et al., 2006; Miao et al., 2016; Somolinos et al., 2008; Wortman and Bissonnette, 1988). Wortman and Bissonnette (1988) demonstrated that E. coli showed that recovery inhibition in tryptic soy broth (TSB) with 0.3% yeast extract in the presence of metabolic inhibitors following exposure to acid. The recovery of pulsed electric field (PEF, 50 pulses, 12 kV/cm)-injured Saccharomyces cerevisiae is inhibited in sabouraud broth containing nalidixic acid or sodium azide, indicating that PEF-induced injuries are related to energy production or nucleic acid synthesis, respectively (Somolinos et al., 2008). For the agar recovery method, microbial cells treated with antimicrobials are spread plated onto agar medium with and without metabolic inhibitors at a fixed concentration (Ha and Kang, 2015; Sawai et al., 1994). After incubation, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values or colony counts are evaluated and used to probe the sites targeted by the corresponding to the metabolic inhibitor. Although measurement methods using metabolic inhibitors can be used to determine the site of injury or to investigate the metabolism of damaged microbial cells, the results of these methods could differ depending on the mode of application method. However, the correlation between the results obtained upon using measurement methods using metabolic inhibitors with their mode of application has not been studied in detail. Thus, it is necessary to design standard protocols by comparing the results of various methods using metabolic inhibitors.

Therefore, in this study, we compared and evaluated the results of the following three measurement methods using metabolic inhibitors: (i) antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method, ii) metabolic inhibitor fixed broth dilution method, and (iii) metabolic inhibitor fixed agar recovery method, for determining the injured sites and metabolism of E. coli O157:H7 in the presence of six selective antimicrobials known to be their antimicrobial mechanism in microbial cells.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain and cell suspensions

Escherichia coli O157:H7 ATCC 35150 was obtained from the bacterial culture collection of Chung-Ang University (Anseong-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea). E. coli O157:H7 ATCC 35150 strain was isolated from human feces of patients suffering from an outbreak of gastrointestinal illness in 1982 (Markell et al., 2015). The strains have been reported to be resistant to heat, acid, and antibiotics such as nalidixic acid. Thus, we selected and tested strain as a representative foodborne bacteria in our study. E. coli O157:H7 was cultured in TSB (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA) at 37 °C for 24 h, harvested by centrifugation at 6000×g for 5 min at 4 °C, and washed once with sterilized 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2). The cell pellets were resuspended in 0.1 M PBS to prepare a bacterial culture with a concentration of approximately 107–108 CFU/mL.

Preparation of antimicrobials and metabolic inhibitors

Six types of antimicrobials were used in the assays, i.e., ethanol (Daejung Chemical Co., Siheung-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, Sigma-Aldrich, Louis, MO, USA), polymyxin B (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.4% thymol (Samchun Pure Chemicals Co., Pyeongtaek-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea), acetic acid (Samchun), and citrus fruit extract (GS-500, Seoul Food R&D Co. Ltd., Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea, 75% citrus extract, 25% refined water). Solutions of 50% ethanol (v/v), 0.5 M EDTA (w/v), 0.2% polymyxin B (w/v), 2% acetic acid (v/v), and 2% citrus fruit extract (v/v) were prepared in sterile distilled water. A stock solution (10%, v/v) of thymol was prepared in 95% ethanol, and the working solution (0.4%, v/v) was prepared in sterile distilled water. The solutions were filtered through a syringe filter (0.45-μm pore size; Advantec, Toyo Roshi Kaisha, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) before use.

To investigate the sites of cellular injury, the following metabolic inhibitors were used: chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, rifampicin, penicillin, D-cycloserine, streptomycin, and cerulenin. All metabolic inhibitors were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The synthesis inhibition targets of these metabolic inhibitors are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)a (µg/mL) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)b (µg/mL) of various antimicrobials and metabolic inhibitors against Escherichia coli O157:H7

| Chemicals | Target of synthesis inhibition | MIC (µg/mL) | MBC (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobials | |||

| Ethanol | 62,500 | > 250,000 | |

| EDTA | 364 | 5816 | |

| Polymyxin B | 8 | 8 | |

| Thymol | 1000 | 2000 | |

| Acetic acid | 2500 | 5000 | |

| Citrus fruit extract | 78 | 2500 | |

| Metabolic inhibitors | |||

| Chloramphenicol | Mitochondrial translation, protein | 1.56 | 6.25 |

| Nalidixic acid | DNA replication | 25.00 | 50.00 |

| Rifampicin | RNA polymerase | 12.50 | 25.00 |

| Penicillin | Cell wall, peptidoglycan | 25.00 | 100.00 |

| D-cycloserine | Peptidoglycan | 50.00 | 100.00 |

| Streptomycin | Protein | 12.50 | 50.00 |

| Cerulenin | Lipid and fatty acid | 125.00 | 500.00 |

aMIC was determined as the minimum concentration that resulted in < 0.4 optical density at 595 nm

bMBC was determined as the minimum concentration that resulted in < 0.1 optical density at 595 nm

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)

The MIC and MBC values of antimicrobials and metabolic inhibitors were determined for E. coli O157:H7 using the broth dilution method. The antimicrobials or metabolic inhibitors and 2 × TSB (150 µL each, 1:1, v/v) were mixed in a 96-well plate (SPL, Pochon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea). Serial twofold dilutions were performed using 100 µL of TSB. Each well was then inoculated with 15 µL of the cultured E. coli O157:H7 (107–108 CFU/mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the optical densities of the cultures were measured using a microplate reader (SpectraMax M2, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) at 595 nm. The MIC and MBC values were determined at the lowest concentration based on the turbidity of two cultures at the same concentration; this exercise revealed that optical densities at 595 nm were < 0.4 and 0.1, respectively.

Measurement for target injury site of antimicrobial using metabolic inhibitors

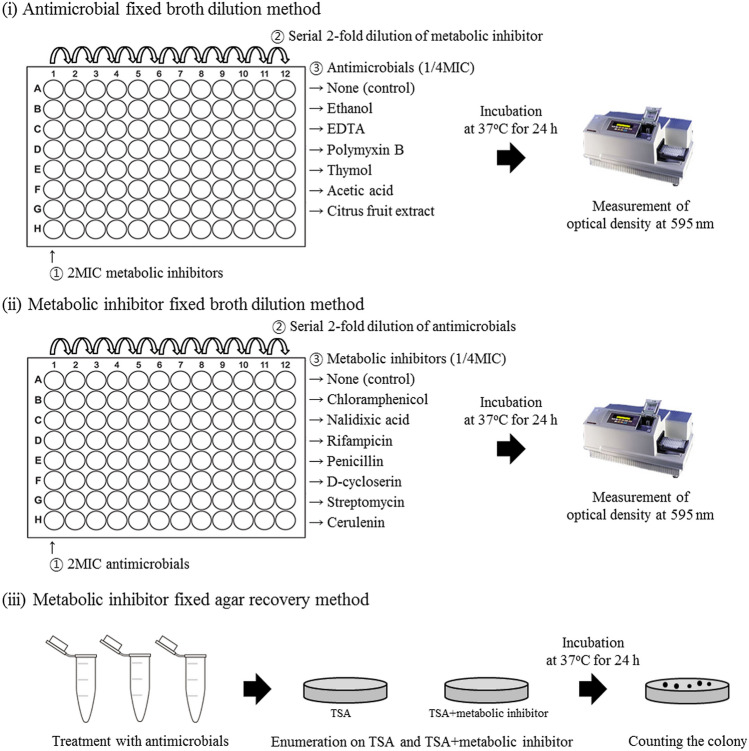

To compare the measurement methods of the injury site using metabolic inhibitors, three different methods were used to evaluate the injured site of E. coli O157:H7 treated with antimicrobials. This study supposed that antimicrobial injured cells have different sensitivities to metabolic inhibitors which promote specific inhibitory actions on bacteria, and 7 metabolic inhibitors. The experimental process of three different methods for determining the target injury site are illustrated in Fig. 1.

-

(i)

The antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method was performed as described previously (Miao et al., 2016) with some modifications. E. coli O157:H7 was cultured in TSB (Difco) at 37 °C for 24 h. Then, 2 × TSB and 2MIC metabolic inhibitors (1:1, v/v; 150 µL each) were mixed in a 96-well plate (SPL). Serial twofold dilutions were performed using 150 µL of TSB. Each well was then inoculated with 150 µL of 1/4 MIC antimicrobials and then inoculated with 15 µL E. coli O157:H7 suspension (107–108 CFU/mL). All 96-well plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the MIC and MBC values were determined as described above. Notably, the MIC and MBC values for cells exposed to a combination of antimicrobials and metabolic inhibitors were lower than those for cells exposed to antimicrobials alone (without metabolic inhibitors).

-

(ii)

The metabolic inhibitor fixed broth dilution method was used as previously described (García et al., 2006; Somolinos et al., 2008; Wortman and Bissonnette, 1988) with some modifications. E. coli O157:H7 was cultured in TSB (Difco) at 37 °C for 24 h. Then, 2 × TSB and 2MIC antimicrobials (1:1, v/v; 150 µL each) were mixed in a 96-well plate (SPL). Serial twofold dilutions were performed using 150 µL of TSB. Then, 150 µL of 1/4MIC metabolic inhibitors was added to each well, and then inoculated with 15 µL suspension of E. coli O157:H7 (107–8 CFU/mL). All 96-well plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the MIC and MBC values were determined as described above. It is significant that the MIC and MBC values of cells treated with a combination of metabolic inhibitors and antimicrobial are lower than those of cells treated with metabolic inhibitors alone.

-

(iii)

The metabolic inhibitor fixed agar recovery method was performed as described previously (Ha and Kang, 2015; Sawai et al., 1994) with some modifications. The E. coli O157:H7 suspension was inoculated into the antimicrobials, followed by incubation at room temperature for 1 h. After antimicrobial, 1 mL aliquots of treated cells were serially diluted tenfold in 9 mL of 0.2% peptone water (Difco). Then, 100 µL of the diluted suspension was plated onto TSA medium with or without metabolic inhibitors. In preliminary studies, the concentrations of metabolic inhibitors were chosen that they did not significantly reduce the culturable cells (data not shown). All plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, followed by colony enumeration. Based on the difference in the number of colonies obtained on TSA medium with and without a metabolic inhibitor the site of injury corresponding to the specific metabolic inhibitor was determined.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the three different methods used for determining the cell injury site in this study. (i) Antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method; (ii) Metabolic inhibitor fixed broth dilution method; and (iii) Metabolic inhibitor fixed agar recovery method

Statistical analysis

The average of duplicate plate counts from three replicates were converted to log CFU/mL. Data were analyzed using ANOVA in SAS (Version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for a completely randomized design. When the main effect was significant (p ≤ 0.05), mean separation was accomplished using Duncan’s multiple range test.

Results and discussion

MIC and MBC values of antimicrobials and metabolic inhibitors

The MIC and MBC values for six antimicrobials (ethanol, EDTA, polymyxin B, thymol, acetic acid, and citrus fruit extract) and seven metabolic inhibitors (chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, rifampicin, penicillin, D-cycloserine, streptomycin, and cerulenin) against E. coli O157:H7 are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The MIC and MBC values of the antimicrobials ranged from 8–62,500 μg/mL and 8–250,000 μg/mL, respectively (Table 1). Polymyxin B had low MIC and MBC values of 8 μg/mL against E. coli O157:H7. The MIC and MBC values of metabolic inhibitors ranged from 1.56–125.00 μg/mL and 6.25–500.00 μg/mL, respectively (Table 1). Metabolic inhibitors that induce cell death have been studied and can be classified into four classes based on their killing mechanisms: inhibition of DNA synthesis (nalidixic acid), inhibition of RNA synthesis (rifampicin), inhibition of cell wall synthesis (penicillin, D-cycloserine, and cerulenin), and inhibition of protein synthesis (chloramphenicol and streptomycin) (Kohanski et al. 2010). Wortman and Bissonnette (1988) investigated the MIC value of metabolic inhibitors against E. coli B/5 and their MIC values for cerulenin, chloramphenicol, D-cycloserine, nalidixic acid, and rifampicin were 62.5, 1.9, 125.0, 1.9, and 31.2 μg/mL, respectively. Somolinos et al. (2008) observed that the MIC value for S. cerevisiae ranged from 2.3–1000.0 μg/mL when treated with chloramphenicol, rifampicin, cerulenin, and nalidixic acid. This discrepancy in MIC values between the present and previous studies might be due to the difference in bacterial strains.

Table 2.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)a (µg/mL) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)b (µg/mL) of metabolic inhibitors combined with antimicrobials against Escherichia coli O157:H7 using an antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method

| Antimicrobials (µg/mL) | Combined with metabolic inhibitors (µg/mL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloramphenicol | Nalidixic acid | Rifampicin | Penicillin | D-cycloserine | Streptomycin | Cerulenin | |

| (a) MIC | |||||||

| None | 1.56 | 25.00 | 12.50 | 25.00 | 50.00 | 12.50 | 125.00 |

| Ethanol (15,625) | 3.13 | 25.00 | 1.56 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 6.25 | 250.00 |

| EDTA (91) | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.39 | 6.25 | 0.10 | 0.49 |

| Polymyxin B (2) | 1.56 | 25.00 | 0.39 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 12.50 | 500.00 |

| Thymol (250) | 0.78 | 12.50 | 3.13 | 12.50 | 6.25 | 1.56 | 250.00 |

| Acetic acid (625) | 3.13 | 25.00 | 6.25 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 12.50 | 250.00 |

| Citrus (19.5) | 0.39 | 6.25 | 1.56 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 12.50 | 250.00 |

| (b) MBC | |||||||

| Nonec | 6.25 | 50.00 | 25.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 50.00 | 500.00 |

| Ethanol (15,625) | 25.00 | 100.00 | > 100.00 | > 100.00 | 100.00 | 50.00 | 500.00 |

| EDTA (91) | 12.50 | 50.00 | 12.50 | 50.00 | 50.00 | 50.00 | 500.00 |

| Polymyxin B (2) | 12.50 | 50.00 | 0.78 | 100.00 | > 100.00 | 50.00 | > 500.00 |

| Thymol (250) | 6.25 | 50.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 50.00 | 100.00 | > 500.00 |

| Acetic acid (625) | 12.50 | 50.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 50.00 | 100.00 | > 500.00 |

| Citrus (19.5) | 6.25 | 50.00 | 50.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 500.00 |

aMIC was determined as the minimum concentration that resulted in < 0.4 optical density at 595 nm

bMBC was determined as the minimum concentration that resulted in < 0.1 optical density at 595 nm

cNone, TSB without metabolic inhibitor

Measurement of injury sites targeted by antimicrobials against E. coli O157:H7 using the antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method

The effects of metabolic inhibitors on the recovery of E. coli O157:H7 injured by an antimicrobial were estimated using an antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method (Table 2a, b). The difference in MIC and MBC values based on absorbance (OD595) obtained with and without metabolic inhibitors can be used to estimate the injury sites targeted by the antimicrobials. Compared to the results of the control (no antimicrobial treatment and only metabolic inhibitors added), the MICs of ethanol were decreased in the presence of rifampicin, D-cycloserine, and streptomycin (Table 2a). In particular, treatment with EDTA exhibited lower MIC values in TSB supplemented with all metabolic inhibitors compared to the control. On the other hand, treatment with polymyxin B exhibited lower MIC values in the presence of rifampicin and D-cycloserine. Treatment with thymol also resulted in lower MIC values in TSB supplemented with all metabolic inhibitors except for cerulenin. These results suggest that the antibacterial effects of EDTA and thymol might result from multi-damage to the metabolism associated with DNA, RNA, protein, and cell wall in E. coli O157:H7. The antibacterial activity of ethanol, polymyxin B, and acetic acid against E. coli O157:H7 may occur due to damaged RNA (rifampicin) and peptidoglycan synthesis (D-cycloserine). On the contrary, treatment with antimicrobials showed higher MBC values in TSB supplemented with all metabolic inhibitors compared to those in the control (Table 2b). Thus, it is difficult to estimate the sites targeted by the antimicrobials in E. coli O157:H7 based on the MBC value. Miao et al. (2016) reported that a bacteriocin (0.5 MIC) increased the inhibitory effect of erythromycin (0.4–2.0 μg/mL) on E. coli growth in Luria–Bertani broth, indicating that bacteriocin may damage the outer membrane. The extent of the outer membrane damage by induced in E. coli by bacteriocin were in agreement with the morphological changes by TEM. However, our studies indicated only weak relationships between the MIC values and antibacterial mechanisms in case of antimicrobials known to damage the membrane.

Measurement of injury sites targeted by antimicrobials against E. coli O157:H7 using the metabolic inhibitor fixed broth dilution method

The effect of metabolic inhibitors on the recovery of E. coli O157:H7 injured by antimicrobials was estimated using the metabolic inhibitor fixed broth dilution method (Table 3a, b). As shown in Table 3a, ethanol had lower MIC values (62,500 µg/mL) in TSB supplemented with rifampicin and streptomycin than in TSB with other metabolic inhibitors. Similar to those from the antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method, results from the metabolic inhibitor fixed broth dilution method indicated that EDTA-treated cells markedly showed increased levels of recovery inhibition in the presence of all metabolic inhibitors except for cerulenin, indicating that EDTA is plays a role in determining cellular injuries at multiple sites including DNA, RNA, protein, and cell wall. Treatment with thymol and acetic acid only resulted in lower MIC values in the presence of nalidixic acid (500 µg/mL) and D-cycloserine (625 µg/mL), respectively. However, treatment with polymyxin B and citrus fruit extract did not result in differences between the MIC values of TSB supplemented with and without all metabolic inhibitors. For MBC values, EDTA and thymol only showed lower MBC values in the presence of rifampicin (364 µg/mL) and nalidixic acid (1000 µg/mL), respectively (Table 3b). Similar to MBC results obtained using the antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method, it was difficult to estimate the injury at sites targeted by antimicrobial treatments against E. coli O157:H7 based on the MBC values. Some studies have previously evaluated the target injury site of bacteria using the metabolic inhibitor fixed broth dilution method (García et al., 2006; Pinto et al., 2017; Somolinos et al., 2008; Wortman and Bissonnette, 1988). Wortman and Bissonnette (1988) reported E. coli showed recovery inhibition in the presence of 0.8 µg/mL chloramphenicol (protein synthesis), 31.2 µg/mL 2,4-dinitrophenol (uncoupling of respiratory), 0.7 µg/mL carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (dissipation of proton motive force), and 12 µg/mL cerulenin (inhibition of lipid synthesis) following exposure to acid mine water (pH 3.02). García et al. (2006) reported that the recovery of PEF-injured E. coli (200 pulses, 25 kV/cm) in 0.1% peptone water in the presence of sodium azide and cerulenin implies that the repair of membrane damage requires energy and lipid synthesis, respectively.

Table 3.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)a (µg/mL) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)b (µg/mL) of antimicrobials combined with metabolic inhibitors against Escherichia coli O157:H7 using a metabolic inhibitor fixed broth dilution method

| Metabolic inhibitor (µg/mL) | Combined with antimicrobials (µg/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | EDTA | Polymyxin B | Thymol | Acetic acid | Citrus | |

| (a) MIC | ||||||

| None | 125,000 | 182 | 4 | 2000 | 1250 | 78 |

| Chloramphenicol (0.39) | > 250,000 | 91 | 8 | 2000 | 1250 | 78 |

| Nalidixic acid (6.25) | 125,000 | 46 | 8 | 500 | 5000 | 78 |

| Rifampicin (3.13) | 62,500 | 46 | 4 | 2000 | 1250 | 78 |

| Penicillin (6.25) | 125,000 | 91 | 8 | 4000 | 1250 | 78 |

| D-cycloserine (12.50) | 125,000 | 91 | 8 | 2000 | 625 | 78 |

| Streptomycin (3.13) | 62,500 | 46 | 4 | 2000 | 1250 | 78 |

| Cerulenin (31.25) | 125,000 | 364 | 8 | 4000 | 1250 | 78 |

| (b) MBC | ||||||

| Nonec | > 250,000 | 1454 | 4 | 4000 | 2500 | 78 |

| Chloramphenicol (0.39) | > 250,000 | > 1454 | 16 | > 4000 | 2500 | 78 |

| Nalidixic acid (6.25) | > 250,000 | > 1454 | 8 | 1000 | > 10,000 | 78 |

| Rifampicin (3.13) | > 250,000 | 364 | 4 | > 4000 | 2500 | 78 |

| Penicillin (6.25) | > 250,000 | > 1454 | 8 | > 4000 | 2500 | 78 |

| D-cycloserine (12.50) | > 250,000 | > 1454 | 8 | > 4000 | 2500 | 78 |

| Streptomycin (3.13) | > 250,000 | > 1454 | 8 | > 4000 | 2500 | 78 |

| Cerulenin (31.25) | > 250,000 | > 1454 | 8 | > 4000 | 2500 | 78 |

aMIC was determined as the minimum concentration that resulted in < 0.4 optical density at 595 nm

bMBC was determined as the minimum concentration that resulted in < 0.1 an optical density at 595 nm

cNone, TSB without metabolic inhibitor

Measurement of injured sites targeted by antimicrobials against E. coli O157:H7 using the metabolic inhibitor fixed agar recovery method

To gain further insights into antimicrobial injury, the effect of metabolic inhibitors on the recovery of E. coli O157:H7 injured by antimicrobials was estimated using the metabolic inhibitor fixed agar recovery method. Figure 2 shows the quantitative levels of recovery inhibition in E. coli O157:H7 treated with antimicrobials. If any cellular site is damaged by antimicrobials, the damaged cells would become more sensitive to specific metabolic inhibitors, resulting in the inability of cells to grow on TSA supplemented with metabolic inhibitors. Treatment with all antimicrobials used in this study did not significantly reduce the levels of E. coli O157:H7 on TSA without metabolic inhibitors (p > 0.05) (data not shown). Compared to the control, the levels of recovery inhibition by ethanol and acetic acid were significantly increased in the presence of nalidixic acid (DNA replication) and rifampicin (RNA polymerase), respectively (Fig. 2a, e). Treatment with polymyxin B inhibited the repair of injury induced by nalidixic acid (2.99 log CFU/mL) and rifampicin (1.69 log CFU/mL) (Fig. 2c). On the contrary, levels of recovery inhibition by thymol were increased in the presence of all metabolic inhibitors compared to those in the control (p ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 2d). In particular, thymol showed higher levels of recovery inhibition in the presence of nalidixic acid (4.09 log CFU/mL) and streptomycin (5.16 log CFU/mL) compared to other metabolic inhibitors. These results suggest that the antibacterial effects of thymol may be due to the presence of multiple sites of injury in E. coli O157:H7. Citrus fruit extract was treated, the E. coli O157:H7 counts were reduced in the presence of nalidixic acid and cerulenin, which inhibit bacterial DNA synthesis and lipid synthesis, respectively (Fig. 2f). On the contrary, no difference in the level of recovery inhibition was observed between all metabolic inhibitors and the control when treated with EDTA (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2b). Several studies have demonstrated injury sites in bacteria using the metabolic inhibitor fixed agar recovery method (Ha and Kang, 2015; Kim et al., 2017; Sawai et al., 1994). Sawai et al. (1994) reported that treatment with far-infrared radiation (FIR) increased the metabolic inhibition of E. coli in phosphate buffered saline by chloramphenicol and rifampicin, indicating that FIR damaged both protein and RNA synthesis. Ha and Kang (2015) observed that the recovery of Salmonella Typhimurium treated with near-infrared heating combined with UV-C irradiation was significantly inhibited on TSA incorporated with chloramphenicol (protein synthesis), nalidixic acid (DNA replication), penicillin (cell wall synthesis), and rifampin (RNA polymerase). Therefore, the inhibitory mechanism of this treatment might involve damage to the related target sites in cells or inhibition of the related target metabolism. Similar to these findings, Kim et al. (2017) found that treatment with 405 nm light-emitting diodes significantly increased the metabolic inhibition of Salmonella Typhimurium by rifampicin.

Fig. 2.

Populations (log10 CFU/mL) of Escherichia coli O157:H7 treated with antimicrobials (MIC) using the metabolic inhibitor (1/4 MIC) fixed agar recovery method. Treatment with ethanol (A); EDTA (B); polymyxin B (C); thymol (D); acetic acid (E); and citrus fruit extract (F). Asterisk (*) indicates a significant (p ≤ 0.05) difference between the populations of E. coli O157:H7 on TSA without metabolic inhibitor (none) and on TSA with metabolic inhibitor

Comparison of measurement methods at evaluating antimicrobial-induced injury in E. coli O157:H7

The effect of metabolic inhibitors on the recovery of E. coli O157:H7 injured by antimicrobials was compared and evaluated to optimize the measurement methods for the injury sites (Table 4). Ethanol exhibited lower MIC values in the presence of rifampicin and streptomycin when used with the antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method. Similar to the results obtained using the antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method, the results of the metabolic inhibitor fixed broth dilution method revealed that ethanol-treated cells had lower MIC values when supplemented with rifampicin and streptomycin. On the other hand, the agar recovery method indicated that treatment with ethanol decreased the level of recovery inhibition in the presence of nalidixic acid. Ethanol exhibits broad spectrum antimicrobial activity against bacteria, viruses, and fungi. The antibacterial mechanism of ethanol is mainly associated with cell membrane damage, rapid protein denaturation, and cell lysis (Dagley et al., 1950). Therefore, these results indicated only weak relationships between MIC values and the antibacterial mechanism of ethanol, which is known to cause membrane damage and protein denaturation.

Table 4.

Summary of minimum inhibitory concentrationa (µg/mL) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)b (µg/mL) against Escherichia coli O157:H7 injured by antimicrobials using three different methods

| Antimicrobials | Broth dilution method | Agar recovery method | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method | Metabolic inhibitor fixed broth dilution method | Metabolic inhibitor fixed agar recovery method | |

| Ethanol |

Rifampicin D-cycloserine Streptomycin |

Rifampicin Streptomycin |

Nalidixic acid |

| EDTA |

Chloramphenicol Nalidixic acid Rifampicinc Penicillin D-cycloserine Streptomycin Cerulenin |

Chloramphenicol Nalidixic acid Rifampicin Penicillin D-cycloserine Streptomycin |

NDd |

| Polymyxin B |

Rifampicin D-cycloserine |

ND |

Nalidixic acid Rifampicin |

| Thymol |

Chloramphenicol Nalidixic acid Rifampicin Penicillin D-cycloserine Streptomycin |

Nalidixic acid |

Chloramphenicol Nalidixic acid Rifampicin Penicillin G D-cycloserine Streptomycin Cerulenin |

| Acetic acid |

Rifampicin D-cycloserine |

D-cycloserine | Rifampicin |

| Citrus fruit extract |

Chloramphenicol Nalidixic acid Rifampicin D-cycloserine |

ND |

Nalidixic acid Cerulenin |

aMIC was determined as the minimum concentration that resulted in < 0.4 an optical density at 595 nm (non-bold letter)

bMBC was determined as the minimum concentration that resulted in < 0.1 an optical density at 595 nm (bold letter)

cND not determined

With EDTA treatment, the antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method showed lower MIC values in the presence of all metabolic inhibitors. Results from the metabolic inhibitor fixed broth dilution method showed that EDTA had a lower MIC value in the presence of all metabolic inhibitors except for cerulenin. EDTA has been reported to remove stabilizing cations such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ from the outer membrane, thereby releasing lipopolysaccharide to the external medium and creating a hydrophobic pathway (Shelef and Seiter, 1993). Thus, these results may be attributed to the fact that the hydrophobic compounds of EDTA can penetrate the outer membrane and reach the site of action in the cytoplasmic membrane. However, the levels of recovery inhibition by EDTA were not significantly different on TSA with metabolic inhibitors compared to the control (p ≤ 0.05). Polymyxin B alters bacterial outer membrane permeability by binding to a negatively charged site in the lipopolysaccharide layer, which shows electrostatic attraction for the positively charged amino groups in the cyclic peptide portion (Nikaido and Vaara, 1985). In the present study, the antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method indicated that synthesis of peptidoglycan (D-cycloserine) or RNA (rifampicin) in of E. coli O157:H7 was affected upon treatment with polymyxin B, whereas recovery inhibition was observed in the presence of nalidixic acid and rifampicin using the agar recovery method. The results of the antimicrobial fixed broth dilution method and agar recovery method indicated that the antibacterial effect of thymol on E. coli O157:H7 may be related to damage at multiple sites, including protein, DNA, RNA, cell wall, peptidoglycan, and lipid and fatty acid synthesis. Helander et al. (1998) reported that thymol destabilizes the cell wall and membrane structure, thus causing leakage of intracellular contents and disruption of proton motive force. In contrast, the results of the metabolic inhibitor fixed broth dilution method indicate that the E. coli O157:H7 counts were only reduced in the presence of nalidixic acid when thymol was used. From these results, it was difficult to identify a correlation between the broth dilution method and agar recovery method. Similar to these findings, treatment with acetic acid and citrus fruit extract also significantly increased the levels of recovery inhibition in E. coli O157:H7, regardless of the measurement method. These results suggest that the antibacterial mechanism of antimicrobials was highly dependent on the measurement method used. In other words, the results of the three methods were not correlated. Accordingly, it may be considered that antimicrobial mechanism of some antimicrobials is very complicated because they are inactivated by several mechanisms. Thus, the use of a measurement method using metabolic inhibitors alone may not be accurate for determining the target injury site of pathogenic bacteria. Indeed, Hyun and Lee (2020) demonstrated that the injury site of LED at blue wavelength in L. monocytogenes and P. fluorescens was revealed based on the agar recovery method, propidium iodide uptake, and transmission electron microscopy. Therefore, various measurement methods should be compared and analyzed to determine the damage or injury site of pathogenic bacteria by antimicrobials. Further studies are thus needed to develop a standardized method for determining the sites targeted by antimicrobials against pathogenic bacteria.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2016R1A2B4014591).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bae YM, Yoon JH, Kim JY, Lee SY. Identifying the mechanism of Escherichia coli O157:H7 survival by the addition of salt in the treatment with organic acid. Journal Applied Microbiology. 2017;124:241–253. doi: 10.1111/jam.13613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman B, Ross T. Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica are protected against acetic acid, but not hydrochloric acid, by hypertonicity. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75:3605–3610. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02462-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagley S, Dawes EA, Morrison GA. Inhibition of growth of Aerobacter aerogenes: the mode of action of phenols, alcohols, acetone, and ethyl acetate. Journal Bacteriology. 1950;60:369–379. doi: 10.1128/jb.60.4.369-379.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García D, Mañas P, Gómez N, Raso J, Pagán R. Biosynthetic requirements for the repair of sublethal membrane damage in Escherichia coli cells after pulsed electric fields. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2006;100:428–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha JW, Kang DH. Enhanced inactivation of food-borne pathogens in ready-to-eat sliced ham by near-infrared heating combined with UV-C irradiation and mechanism of the synergistic bacterial action. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2015;81:2–8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01862-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helander IM, Alakomi H-L, Latva-Kala K, Mattila-Sandholm T, Pol I, Gorris LGM, von Wright A. Characterization of the action of selected essential oil components on gram-negative bacteria. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1998;46:3590–3595. doi: 10.1021/jf980154m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun JE, Lee SY. Antibacterial effect and mechanisms of action of 460–470 nm light-emitting diode against Listeria monocytogenes and Pseudomonas fluorescens on the surface of packaged sliced cheese. Food Microbiology. 2020;86:103314. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2019.103314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin HH, Lee SY. Combined effect of aqueous chlorine dioxide and modified atmosphere packaging on inhibiting Salmonella Typhimurium and Listeria monocytogenes in mungbean sprouts. Journal of Food Science. 2007;72:M441–M445. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Ng BXA, Zwe YH, Yuk HG. Photodynamic inactivation of Salmonella enterica Enteritidis by 405 ± 5-nm light-emitting diode and its application to control salmonellosis on cooked chicken. Food Control. 2017;82:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.06.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Collins JJ. How antibiotics kill bacteria: from targets to networks. Nature Reviews. 2010;8:423–435. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leistner L. Basic aspects of food preservation by hurdle technology. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2000;55:181–186. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LR, Shi YH, Su GF, Le GW. Selectivity for and destruction of Salmonella typhimurium via a membrane damage mechanism of a cell-penetrating peptide pptG20 analogue. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2012;40:337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markell JA, Koziol AG, Lambert D. Draft genome sequence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 ATCC 35150 and a nalidixic acid-resistant mutant derivative. Genome Announcements. 2015;3(4):e00734–e815. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00734-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J, Liu G, Ke C, Fan W, Li C, Chen Y, Dixon W, Song M, Cao Y, Xiao H. Inhibitory effects of a novel antimicrobial peptide from kefir against Escherichia coli. Food Control. 2016;65:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H, Vaara M. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiological Reviews. 1985;49:1–32. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.1-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda-Sana A, Repetto V, Moreno S. Carnosic acid is an efflux pumps modulator by dissipation of the membrane potential in Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2013;29:137–144. doi: 10.1007/s11274-012-1166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto NCC, Campos L, Evangelista ACS, Lemos ASO, Silva TP, Melo RCN, Lourenço CC, Salvador MJ, Apolônio ACM, Scio E, Fabri RL. Antimicrobial Annona muricata L. (soursoap) extract targets the cell membranes of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Industrial Crops and Products. 2017;107:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.05.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rurián-Henares JA, Morales FJ. Antimicrobial activity of melanoidins against Escherichia coli is mediated by membrane-damage mechanism. Journal of Food Chemistry. 2008;56:2357–2362. doi: 10.1021/jf073300+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahalan AZ, Aziz AHA, Hing H, Ghani MKA. Divalent CATIONS (Mg2+, CA2+) protect bacterial outer membrane damage by polymyxin B. Sains Malaysiana. 2013;42:301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Sawai J, Sagara K, Igarashi H, Hashimoto A, Kokugan T, Shimizu M. Injury of Escherichia coli in physiological phosphate buffered saline induced by far-infrared irradiation. Journal of Chemical Engineering of Japan. 1994;28:294–299. doi: 10.1252/jcej.28.294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shelef LA, Seiter JA. Indirect antimicrobial. Vol. 2, pp. 539–569. In: Antimicrobials in Food (Chapter 15). Davidson PM, Branen AL (ed). Marcel Dekker Ltd., New York, NY, USA (1993)

- Somolinos M, García D, Condón S, Mañas P, Pagán R. Biosynthetic requirements for the repair of sublethally injured Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells after pulsed electric fields. Journal Applied Microbiology. 2008;105:166–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan T, Wu D, Li W, Zheng X, Li W, Shan A. High specific selectivity and membrane-active mechanism of synthetic cationic hybrid antimicrobial peptide based on the peptide FV7. International Journal of Molecular Science. 2017;18:1–17. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortman AT, Bissonnette GK. Metabolic processes involved in repair of Escherichia coli cells damaged by exposure to acid mine water. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1988;54:1901–1906. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.1901-1906.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu X, Wang Y, Jiang P, Quek SY. Antibacterial activity and mechanisms of cinnamon essential oil against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Food Control. 2016;59:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]