Abstract

Rhodopsin is the light receptor in rod photoreceptor cells that initiates scotopic vision. Studies on the light receptor span well over a century, yet questions about the organization of rhodopsin within the photoreceptor cell membrane still persist and a consensus view on the topic is still elusive. Rhodopsin has been intensely studied for quite some time and there is a wealth of information to draw from to formulate an organizational picture of the receptor in native membranes. Early experimental evidence in apparent support for a monomeric arrangement of rhodopsin in rod photoreceptor cell membranes is contrasted and reconciled with more recent visual evidence in support of a supramolecular organization of rhodopsin. What is known so far about the determinants of forming a supramolecular structure and possible functional roles for such an organization are also discussed. Many details are still missing on the structural and functional properties of the supramolecular organization of rhodopsin in rod photoreceptor cell membranes. The emerging picture presented here can serve as a springboard towards a more in depth understanding of the topic.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptor, membrane protein, nanodomain, photoreceptor cell, phototransduction, quaternary structure

Introduction

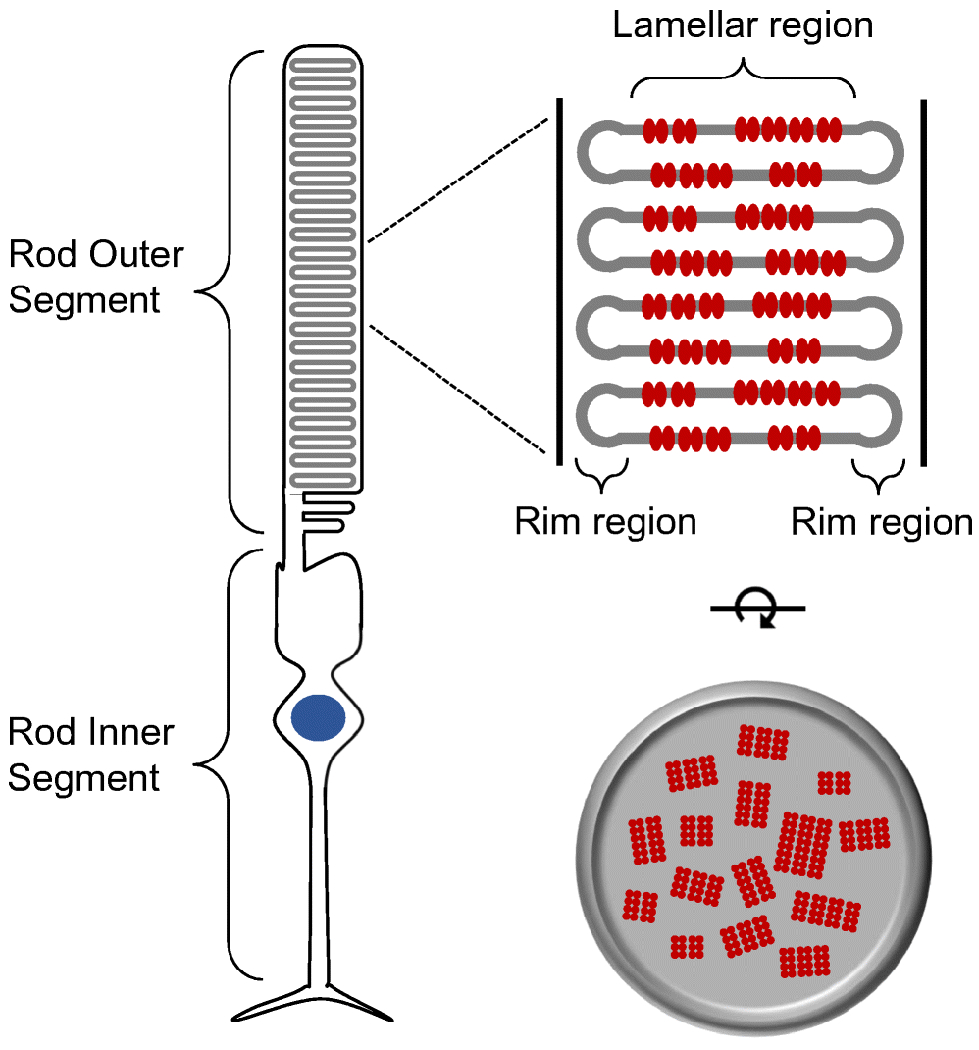

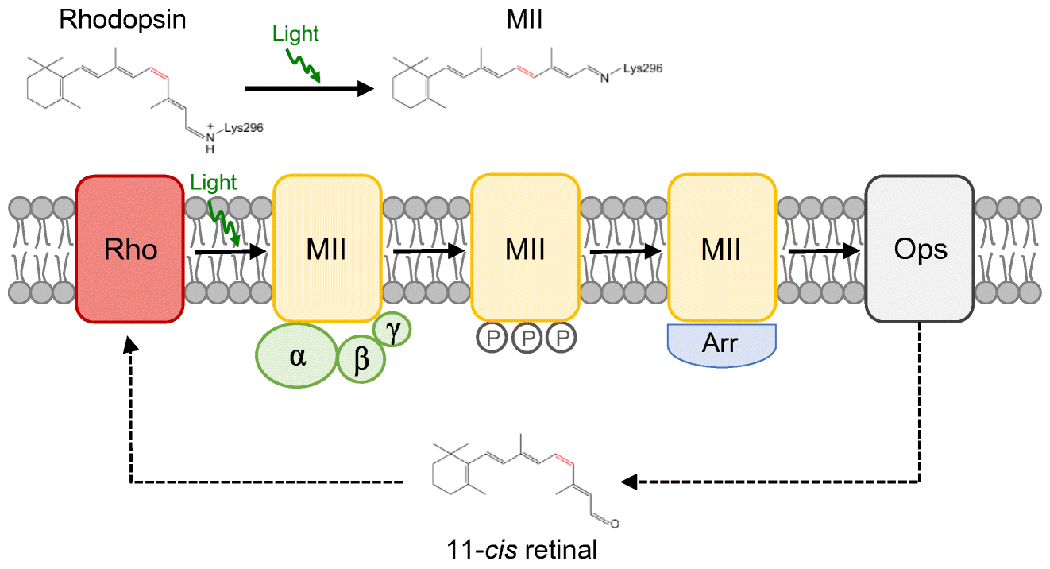

Photoreceptor cells in the outer retina house the machinery to detect photons of light and initiate the first steps of vision. Rhodopsin is the light receptor in rod photoreceptor cells that initiates scotopic vision. The light receptor comprises the apoprotein opsin covalently linked to the chromophore 11-cis retinal. Rod photoreceptor cells are compartmentalized into an outer segment and inner segment (Fig. 1). The rod outer segment (ROS) contains a stack of membranous discs that are encased by a plasma membrane. Rhodopsin is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum in the inner segment and then transported to the outer segment, where it is incorporated into the disc membranes. It is within the ROS disc membranes that rhodopsin initiates a prototypical G protein-mediated signaling cascade called phototransduction upon activation by light [105]. Light promotes the isomerization of 11-cis retinal to all-trans retinal, thereby activating rhodopsin (Fig. 2). Activated rhodopsin engages and activates the heterotrimeric G protein transducin, setting in motion the signaling cascade. The activity of rhodopsin is terminated by phosphorylation by rhodopsin kinase, binding of arrestin, and release of all-trans retinal from its binding pocket.

Figure 1.

Rod photoreceptor cell. Rod photoreceptor cells are compartmentalized into an outer segment and inner segment. The outer segment contains stacks of membranous discs. Rhodopsin (red) is packed into the disc membranes. Figure reprinted from [115], with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 2.

Rhodopsin activity. Rhodopsin (red) is activated when 11-cis retinal is isomerized to all-trans retinal by light. The active state of rhodopsin, MII (yellow), engages and activates the heterotrimeric G protein transducin (green). Rhodopsin is deactivated upon phosphorylation by rhodopsin kinase and binding arrestin (blue). All-trans retinal is released from rhodopsin, leaving the apoprotein opsin (grey). Opsin must be regenerated with 11-cis retinal to reform rhodopsin. Figure adapted from [105], with permission from Elsevier.

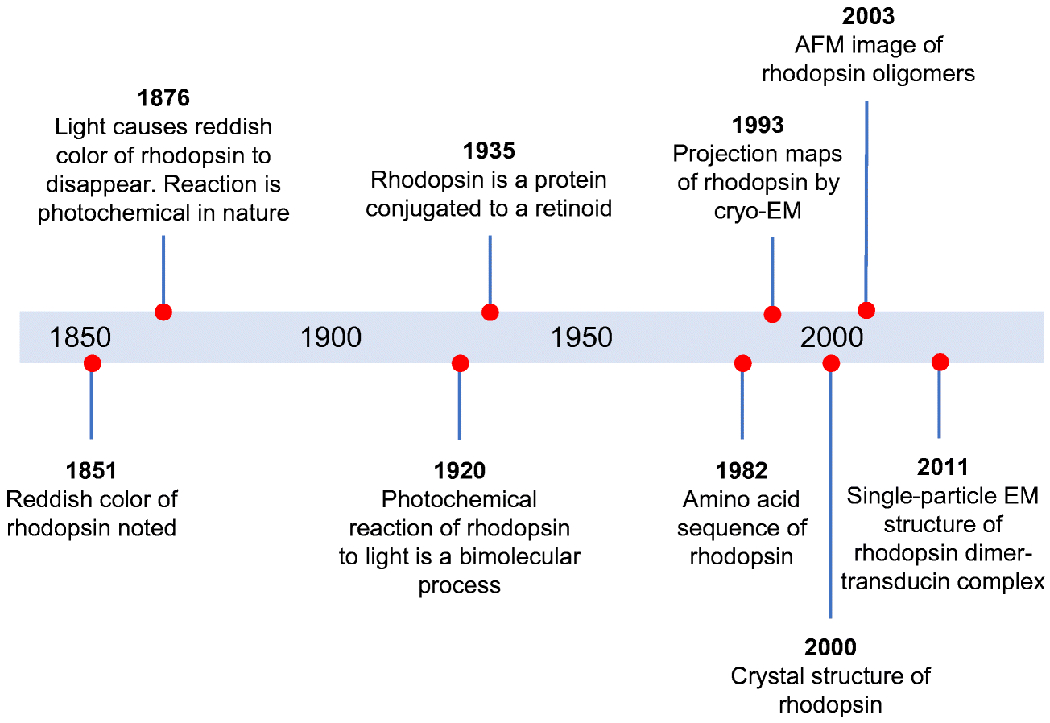

Studies of rhodopsin span well over a century and a half (Fig. 3). Early studies were conducted prior to the molecular identification of rhodopsin and were based on the reddish color of rhodopsin observed in photoreceptor cells [15,72]. The molecular and structural concept of rhodopsin has greatly advanced over more recent times. Structural properties of rhodopsin have only become available in the latter half of the 20th century with the sequencing of the protein molecule in the early 1980s and the determination of a three-dimensional crystal structure in 2000 [53,102,103]. Also in the early 2000s, atomic force microscopy (AFM) would reveal exquisite images of rhodopsin forming a quaternary structure in the form of rows of dimers [42]. Despite the visualization of this supramolecular organization of rhodopsin in native photoreceptor cell membranes, the view that rhodopsin forms oligomers garnered, and continues to garner, much opposition [23,24].

Figure 3.

Timeline highlighting major advancements in our molecular and structural understanding about rhodopsin. Figure adapted from [62], with permission from Elsevier.

The question of whether or not rhodopsin exists and functions as oligomers in nature continues to be debated, generating partisan views on this issue. In this review, the evidence presented in support of both monomeric rhodopsin and oligomeric rhodopsin will be discussed. Given the presented evidence, the most direct methods point to rhodopsin existing as oligomers in photoreceptor cell membranes. The functional role of a supramolecular organization of rhodopsin within the membrane and the determinants of the quaternary structure formed by rhodopsin will also be discussed.

Ambiguity in assessing the oligomeric status of rhodopsin under non-native conditions

The view that rhodopsin exists and functions as a monomer in photoreceptor cell membranes has been the predominant view until more recent times. The question of how rhodopsin is organized within the membrane has been asked since the early molecular characterizations of the light receptor. The technologies were not yet available to directly assess this question, and therefore, the early studies that shaped our molecular view of rhodopsin largely relied on indirect methods to infer the oligomeric status of rhodopsin in photoreceptor cell membranes.

Rhodopsin is a prototypical G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR). The structure of rhodopsin contains 7 α-helical transmembrane domains embedded in a lipid bilayer and an amphipathic helix that sits on the surface of the membrane. Membrane proteins require a lipid bilayer for stability and proper function. Because of the highly hydrophobic nature of membrane proteins like rhodopsin, several manipulations are required to indirectly assess the oligomeric status of the receptor biochemically or biophysically. These manipulations can introduce artifacts and interpretation of the data can be somewhat ambiguous, adding confusion to the discourse on the oligomeric status of rhodopsin.

To make rhodopsin amenable for biochemical or biophysical studies, rhodopsin is often extracted and studied in detergent or reconstituted into an appropriate hydrophobic context for study. Extraction of rhodopsin from the membrane by detergent can result in various forms of the receptor ranging from monomers, dimers, and larger oligomers [38,46,59,87,88,100,101,136]. The presence of detergent can complicate the inference on the oligomeric status of the receptor [24]. and therefore results are often ambiguous. Oligomers of rhodopsin present in the membrane can be disrupted when extracted by detergents [46]. To overcome the effects of detergent during extraction, chemical cross-linking strategies have been employed to examine whether or not rhodopsin formed oligomers within the membrane prior to extraction. Observations using this strategy have been used as evidence for both a monomeric and oligomeric arrangement of rhodopsin [18,35,36,60,70,88,89,134,142]. Results from cross-linking studies are also ambiguous as monomeric species are detected along with oligomeric forms and are often the predominant species. Moreover, the high density of rhodopsin within the membrane can result in cross-linking even in the absence of oligomerization.

Variable results are also found when rhodopsin extracted from native membranes is reconstituted into lipid vesicles or synthetic membranes to mimic the native lipid bilayer environment. Both monomers and dimers have been observed in these artificial lipid bilayers [3,5,6,16,17,83,141,144,150], making assessments on the oligomeric status of the receptor inconclusive. The ambiguity and variability observed in experimental approaches where the receptor is extracted from the membrane or reconstituted back into a lipid bilayer environment highlight the deficiencies of these approaches to assess the oligomeric status of rhodopsin. These approaches are not sufficient in and of themselves to conclude one way or the other on whether or not rhodopsin exists as monomers or oligomers under native conditions. It is therefore imperative to study rhodopsin within the context of the native ROS disc membrane to accurately discern the oligomeric status of the receptor. Although these types of studies are much more complex than those carried out in solution or in artificial lipid bilayers, they are critical in helping us navigate towards a realistic view on the native organization of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes. The discussion here on the evidences in favor of a monomeric or oligomeric arrangement of rhodopsin is largely centered on observations made on rhodopsin in the membrane of rod photoreceptor cells (Table 1).

Table 1:

Studies probing the oligomeric status of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes

| Method | Species | Observations |

| Evidence used to support a monomeric arrangement of rhodopsin | ||

| Microsecond-flash photometry | Frog | Rotational relaxation time of 20 μs determined by transient dichroism induced by bleaching native rhodopsin with a polarized light flash [30]. |

| Saturation transfer electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy | Frog Cow |

Rotational correlation time of 20 μs determined on spin-labeled rhodopsin [4,74]. |

| Microspectrophotometry | Frog Toad Salamander |

Diffusion constant of unlabeled rhodopsin determined to be: frog, 0.4 µm2/s [113]; frog, 0.6 µm2/s [78]; toad, 0.4 µm2/s [50]; frog, 0.3 µm2/s, toad, 0.2 µm2/s, salamander, 0.4 µm2/s [45] |

| Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching | Frog | Diffusion constant of fluorescently labeled rhodopsin determined to be 0.3 µm2/s [148]. Diffusion constant of GFP-tagged rhodopsin determined to be 0.4 µm2/s [145] and 0.1 µm2/s [94], |

| Neutron and X-ray diffraction | Frog Cow |

Rhodopsin is randomly distributed within the plane of the membrane without forming a crystalline lattice [10,11,22,39,120]. |

| Pulsed electron double resonance spectroscopy | Pig | Spin-labeled rhodopsin is randomly distributed within the plane of the ROS disc membrane. Modeling of data is suggestive of monomeric rhodopsin rather than dimeric rhodopsin or a crystalline lattice of rhodopsin [154]. |

| Differential scanning calorimetry | Cow | Partial bleaching of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes had no effect on the thermal denaturation temperatures of rhodopsin and opsin. Based on the premise that oligomers containing both rhodopsin and opsin should affect the thermal denaturation temperature, a monomeric arrangement of rhodopsin was proposed [37]. |

| Freeze-fracture/etch electron microscopy | Toad | Particles 6 nm in size observed at a density of about 30,000 µm− randomly distributed on the membrane surface [118]. |

| Direct evidence in support of an oligomeric arrangement of rhodopsin | ||

| Atomic force microscopy (AFM) | Human, mouse, cow, frog | Oligomeric rhodopsin forming nanodomains were visualized in native ROS disc membranes [19,43,76,77,114–116,122,127–129,149] |

| Cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) | Mouse | Parallel rows of dimeric rhodopsin were detected in averaged subtomograms of the ROS disc membrane [49]. |

| Total internal fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy | Frog | Clusters of rhodopsin labeled with a fluorescently labeled Fab fragment were visualized in ROS discs and exhibited a diffusion coefficient of 0.2 µm2/s [54]. |

Evidence for a monomeric arrangement of rhodopsin

Assessments on the status of rhodopsin within native ROS disc membranes was approached early on by monitoring the diffusion of rhodopsin within the membrane. The rotational diffusion of rhodopsin within ROS disc membranes was quantified by the decay of photodichroism using microsecond-flash photometry and saturation transfer electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy of spin-labeled rhodopsin [4,30,74]. Both methods gave consistent results and indicated a rapid rotational diffusion of rhodopsin within ROS disc membranes. This rapid rotational diffusion as well as effects of glutaraldehyde cross-linking on the rotational diffusion of rhodopsin was used as evidence in support of a monomeric arrangement of rhodopsin [30,36]. Later saturation transfer electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy studies on rhodopsin reconstituted into lipid vesicles, however, indicated that the measured rhodopsin rotational diffusion in ROS disc membranes may be consistent with dimeric or oligomeric forms of the receptor[73].

The lateral diffusion of rhodopsin was also monitored in native ROS disc membranes. Diffusion coefficients were initially determined using microspectrophotometry by bleaching rhodopsin in a large area of the ROS and monitoring the diffusion of unbleached rhodopsin back into that area. More recently, fluorescence microscopy has been utilized to determine the diffusion coefficient. In this case, rhodopsin is either covalently labeled with a small fluorescent molecule or fused with green fluorescent protein (GFP) and expressed in transgenic animals. Fluorescence in an area of the ROS is bleached and the recovery of fluorescence in this area is monitored. Both methods provided equivalent estimates of the diffusion coefficient, ranging from 0.1 – 0.6 μm2/s [45,50,78,94,113,145,148]. Most of the earlier studies stated a diffusion coefficient in the upper part of this range, which was indicative of freely diffusing rhodopsin predicted to be monomeric.

Almost all of the studies to date bleach a large area of the ROS, and therefore the diffusion coefficient is determined by relatively low spatial resolution methods. Since all of these studies were examined in amphibian ROS, which exhibits several deeply penetrating incisures segmenting the disc into lobes, many of the studies use a correction factor to compute the diffusion coefficient. In one study, multiphoton fluorescence microscopy was utilized to achieve higher spatial resolution to examine the diffusion behavior of rhodopsin within a single lobe of the ROS disc, thereby eliminating the need for a correction factor [94]. This higher resolution method resulted in a diffusion coefficient of 0.1 μm2/s, which is on the lower end of the range of reported diffusion coefficients. Interestingly, the non-corrected diffusion coefficients in many of the studies reported here were in the range of 0.1μm2/s [45,113,145]. Thus, the lower end of the range of diffusion coefficients may best represent the diffusion of rhodopsin within ROS disc membranes. The diffusion of rhodopsin may be a poor indicator of oligomeric status of rhodopsin since the variance in the observed diffusion coefficients can be consistent even with relatively large rhodopsin oligomers [94]. Moreover, single-molecule tracking methods reveal a more complex diffusion behavior of rhodopsin within ROS disc membranes, where multiple diffusion states of rhodopsin are detected within a single ROS disc [54].

Early neutron and X-ray diffraction studies indicated that rhodopsin is randomly distributed within the plane of the membrane and does not form a crystalline lattice with regular ordering [10,11,22,120]. More recent studies using small-angle neutron and x-ray scattering and pulsed electron double resonance spectroscopy on spin-labeled rhodopsin also support the absence of a crystalline lattice of rhodopsin and the data have been interpreted as rhodopsin monomers randomly dispersed within the plane of the membrane [39,154]. While these observations clearly rule out a static crystalline lattice arrangement of rhodopsin, it is unclear whether or not these observations are in contradiction to some of the oligomeric arrangements discussed here later on.

More recently, a differential scanning calorimetry study on ROS disc membranes was used to indirectly assess the oligomeric status of rhodopsin by examining the effect of partial bleaching of rhodopsin on the thermal denaturation temperatures of rhodopsin and opsin, which have distinct denaturation profiles [37]. The basic premise of this study was that if rhodopsin forms oligomers, then partial bleaching should result in oligomers containing both rhodopsin and opsin, which in turn should impact the observed thermal denaturation temperatures. The thermal denaturation temperatures were unaffected by the level of bleaching of rhodopsin, and therefore the data were interpreted as rhodopsin being present in ROS disc membranes as monomers. In another differential scanning calorimetry study on ROS disc membranes, partial bleaching of rhodopsin also did not affect the thermal denaturation temperature but it did affect the calorimetric enthalpy change associated with the denaturation of the receptor [67], which is indicative of the formation of rhodopsin oligomers. As indicated in this study, the thermal denaturation temperature may be a poor indicator of environmental changes of rhodopsin and that the calorimetric enthalpy change is a more sensitive parameter to detect environmental changes, including the formation of rhodopsin oligomers.

Early attempts to visualize the organization of rhodopsin within ROS disc membranes have been attempted by freeze-fracture/etch electron microscopy (EM). Particles roughly the size of a rhodopsin monomer randomly distributed within the membrane at a density of about 30,000 μm−2 suggested perhaps that rhodopsin is present as monomers in the ROS disc membrane [118]. Other freeze-fracture/etch EM studies have given variable estimates on particle size and density within the membrane, and it has been questioned whether or not the observed particles accurately reflect the organization of rhodopsin molecules within the membrane due to possible artifacts introduced during sample preparation [26,31,71,99,118]. Bacteriorhodopsin is trimeric and forms a crystalline lattice in purple membrane. However, even with this well-defined structure and stoichiometry, freeze-fracture EM images do not clearly show this supramolecular structure and the observed particles represented a cluster of up to 12 bacteriorhodopsin molecules [12,41]. Thus, freeze-fracture/etch EM may not be suitable to differentiate between a monomeric versus oligomeric arrangements of rhodopsin within the membrane.

The observations in early studies monitoring the diffusion of rhodopsin within the ROS disc membranes (Table 1), along with those from neutron and x-ray scattering and freeze-fracture EM studies, were used to paint a picture of a monomeric rhodopsin freely diffusing and randomly dispersed within the plane of the ROS disc membrane. These studies were only an indirect assessment of the organization of rhodopsin within the ROS disc membrane, and although consistent with a monomeric arrangement, an oligomeric arrangement of the receptor could not necessarily be ruled out. More advanced methods allowing for the visualization of rhodopsin within ROS disc membranes would be needed to arrive at a more realistic picture.

Evidence for an oligomeric arrangement of rhodopsin

Evidence for rhodopsin oligomers have become more direct and less ambiguous with the advancement of biophysical approaches that avoid some of the pitfalls of biochemical approaches described earlier. Methods utilizing Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET) and fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy have demonstrated that rhodopsin forms oligomers in the membrane of live cells [29,46,47,90]. In these methods, rhodopsin is tagged with fluorescent proteins and heterologously expressed in immortalized cells such as COS, HEK293, or Chinese hamster ovary cells. These heterologous expression systems provide a cellular context in which to examine the oligomeric status of rhodopsin, however, they may not fully mimic the unique cellular environment provided by rod photoreceptor cells. For instance, the plasma membrane in the heterologous expression systems will provide a different environment compared to the specialized membranous discs in the ROS of photoreceptor cells (Fig. 1) and the density of rhodopsin in native ROS discs membranes is at least an order of magnitude or greater compared to that in heterologous expression systems [29,90].

Both indirect and direct evidence for an oligomeric arrangement of rhodopsin is available from observations made in rod photoreceptor cells or ROS disc membranes. Indirect evidence includes observations of a trans-phosphorylation mechanism observed in mice where nonactivated rhodopsin can be phosphorylated by rhodopsin kinase when activated rhodopsin is present [135]. Although trans-phosphorylation may be possible in the absence of rhodopsin oligomerization, the most straightforward explanation would involve an active rhodopsin within an oligomer recruiting rhodopsin kinase to facilitate the phosphorylation of inactive rhodopsin present within the same oligomeric complex. Another piece of indirect evidence comes from observations of mislocalization of rhodopsin in rod photoreceptor cells when peptides corresponding to transmembrane helix 1 (TM1) and helix 8 (H8) of rhodopsin were injected subretinally in the eyes of mice [156]. Rhodopsin mislocalization was attributed to the disruption of rhodopsin oligomerization by the competing peptides, and implies that rhodopsin oligomerization is occurring in the endoplasmic reticulum. Alternate explanations independent of rhodopsin oligomerization were not ruled out, such as a general disruption of rhodopsin biosynthesis caused by the peptides. While these indirect evidences are consistent with the notion of an oligomeric arrangement of rhodopsin, more direct evidence is required.

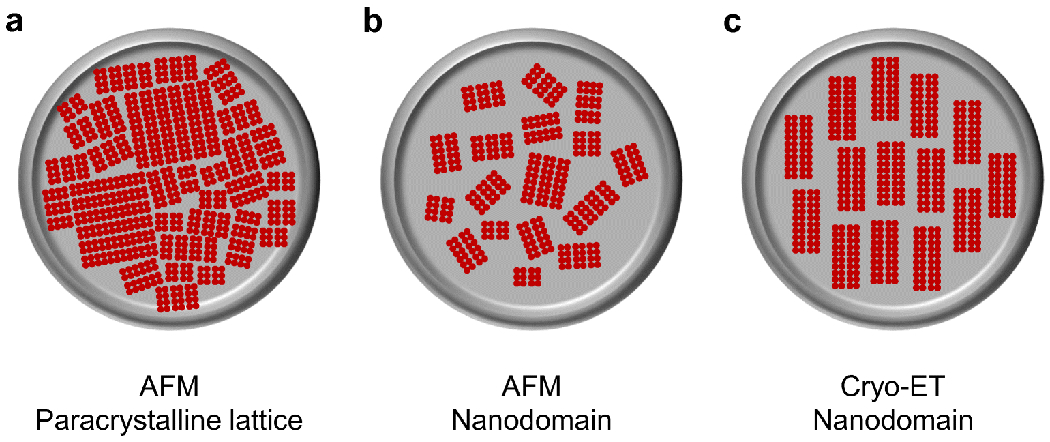

The most direct evidence for an oligomeric arrangement of rhodopsin in the membranes of rod photoreceptor cells has come from the advanced microscopy methods of AFM and cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) (Table 1). The first direct visualization of rhodopsin oligomers within the ROS disc membrane of photoreceptor cells came from AFM. The first AFM study displayed two types of arrangements, a densely packed paracrystalline lattice arrangement and a nanodomain arrangement [42,76]. In both arrangements, rhodopsin forms parallel rows of dimers of variable lengths (Figs. 4A and 4B). In all subsequent AFM studies by multiple groups, the paracrystalline lattice arrangement was not observed and only the nanodomain arrangement was observed [19,43,77,114–116,122,126–129,149]. On occasion, a crystalline lattice was observed in the rim region of the ROS disc [19,43], a region that is devoid of rhodopsin [92]. The nanodomain organization of oligomeric rhodopsin is observed in ROS disc membranes from the retina of humans, mice, frogs, and cows, indicating that this arrangement is conserved among vertebrates. The size of rhodopsin nanodomains and oligomers is heterogenous, with a predominant nanodomain size of about 340 nm2, corresponding to an oligomer containing 24 rhodopsin molecules [115,128].

Figure 4.

Different supramolecular arrangements of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes observed by AFM and cryo-ET. A. Rhodopsin arranged in rows of dimers of variable lengths forming a densely packed paracrystalline lattice. B. Rhodopsin arranged in rows of dimers of variable lengths forming nanodomains. C. Rhodopsin arranged in rows of dimers forming nanodomains mostly of uniform size and aligned parallel to the incisure.

The departure from accepted dogma that rhodopsin is monomeric in photoreceptor cell membranes resulted in immediate criticisms of AFM images displaying an oligomeric arrangement of rhodopsin. The criticisms centered on possible artifacts related to sample preparation and an apparent discrepancy with the rapid diffusion of rhodopsin [23], which was observed in studies discussed earlier (Table 1). Possible artifacts related to sample preparation included effects of disruption of discs and phase separation of lipids due to low temperatures used during sample preparation. These possibilities, however, have been ruled out in subsequent AFM studies. Rhodopsin nanodomains are observed in both intact discs and in disrupted single-bilayer discs [116], indicating that the nanodomain organization of rhodopsin is not an artifact of ROS disc disruption. Rhodopsin nanodomains are observed in ROS disc membranes of cold-blooded frogs [116]. Frogs do not exhibit phase separation of lipids at low temperatures [22], thereby indicating that the nanodomain formation by rhodopsin is not caused by lipid phase separation. Additionally, neither adsorption of ROS disc membranes on a mica substrate nor the lateral forces imparted on the sample by the AFM tip were shown to induce the nanodomain formation of rhodopsin observed in ROS disc membranes [114,116]. Thus, observations of oligomeric rhodopsin forming nanodomains appears to be a physiological arrangement rather than an artifactual arrangement.

Further support of the nanodomain organization of oligomeric rhodopsin observed by AFM has come from studies utilizing total internal fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy and cryo-ET. TIRF microscopy revealed clusters of rhodopsin labeled with a fluorescently tagged Fab fragment of an anti-rhodopsin antibody in the disc membrane of fragmented frog ROS [54]. Although the resolution was not sufficient to observe individual rhodopsin molecules within a cluster, the clusters were consistent with the nanodomains observed by AFM.

Cryo-ET of cryosectioned vitrified murine retina revealed nanodomains of rhodopsin oligomers within ROS disc membranes [49]. The low signal-to-noise in cryo-ET required averaging of hundreds of subtomograms to detect parallel rows of rhodopsin dimers, which were similar to those observed by AFM. In contrast to AFM images, however, only 2 parallel rows of dimers were detected rather than the multiple parallel rows of dimers observed by AFM (Figs. 4B and 4C). The distribution of these rows of dimers and the size of the clusters within an entire ROS disc is unclear in unaveraged tomograms. The study purports a mostly uniform size and distribution of rhodopsin oligomers of about 10 dimers in length, a 20-mer (Fig. 4C). This description contrasts with observations by AFM and a lower resolution cryo-ET tomogram of intact vitrified murine ROS, which displayed a heterogeneous organization of rhodopsin within the ROS disc membrane that is more consistent with the nanodomains observed by AFM [96]. Regardless, computational studies indicate that both rhodopsin nanodomain organizations revealed by AFM and cryo-ET result in similar advantages in signaling properties [117]. The cryo-ET study also suggests that the dimeric rows of rhodopsin are aligned with the incisure of the ROS disc. This alignment is not observed by AFM and has not yet been confirmed by other methods. Incisures are fragile structures and are mostly disrupted in ROS disc membranes visualized by AFM and are only sporadically detected [114]. Thus, there is a possibility that the alignment of rhodopsin dimers is disrupted in AFM studies.

The observed rotational and lateral diffusion of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes is often used as an argument in favor of a monomeric arrangement of rhodopsin [23], as discussed earlier (Table 1). But is the detected mobility and diffusion of rhodopsin within the membrane contradictory to the concept of rhodopsin oligomers and nanodomains? The early focus on the densely packed paracrystalline lattice arrangement of rhodopsin visualized in the first AFM study, an arrangement where rhodopsin is predicted to be relatively immobile, may have led to an incorrect assumption that an oligomeric arrangement of rhodopsin contradicts the observed rapid diffusion of rhodopsin. The physiological arrangement of rhodopsin appears to be one where rhodopsin oligomers form nanodomains. The predominant size of rhodopsin nanodomains detected by AFM is about 340 nm2 [115,128]. As noted earlier, reported diffusion coefficients of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes range from 0.1-0.6 μm2/s (Table 1). The lower end of this range is likely the most accurate and would not be inconsistent with the presence of relatively large rhodopsin oligomers [94]. In fact, nanoscale lipid rafts with diameters of 10 nm are predicted to have diffusion coefficients of 0.2 μm2/s [28]. The previously discussed clusters of rhodopsin in frog ROS disc membranes detected by TIRF microscopy also exhibited a diffusion coefficient of 0.2 μm2/s [54]. Thus, nandomains of oligomeric rhodopsin can be quite mobile within the ROS disc membrane and this organization can be consistent with the reported diffusion coefficients.

The evidence for rhodopsin oligomers using AFM, cryo-ET, and TIRF microscopy (Table 1) all paint a common picture where rows of rhodopsin dimers form nanodomains within the ROS disc membrane. Some differences are apparent among the different studies in terms of the organization and size of the oligomeric rhodopsin nanodomains (Figs. 4B and 4C). The similarities form a foundation on which to build and the differences in some of the details present areas to be investigated further.

What are the determinants of the oligomeric status of rhodopsin?

Each ROS contains several hundred discs (Fig. 1) and the properties of these discs are heterogeneous. There is both a functional and membrane compositional heterogeneity exhibited by discs that is dependent on the axial location of the disc in the ROS [1,2,7,14,20,81,86,152,155]. This heterogeneity is also reflected in the packing of rhodopsin within the membrane of ROS discs as quantitative analysis of AFM images displays heterogeneity in the properties of discs [114,149]. It is unclear what underlies this heterogeneity among individual discs and the factors that contribute to this heterogeneity. For the discussion here, only the average behavior of rhodopsin within ROS discs is considered.

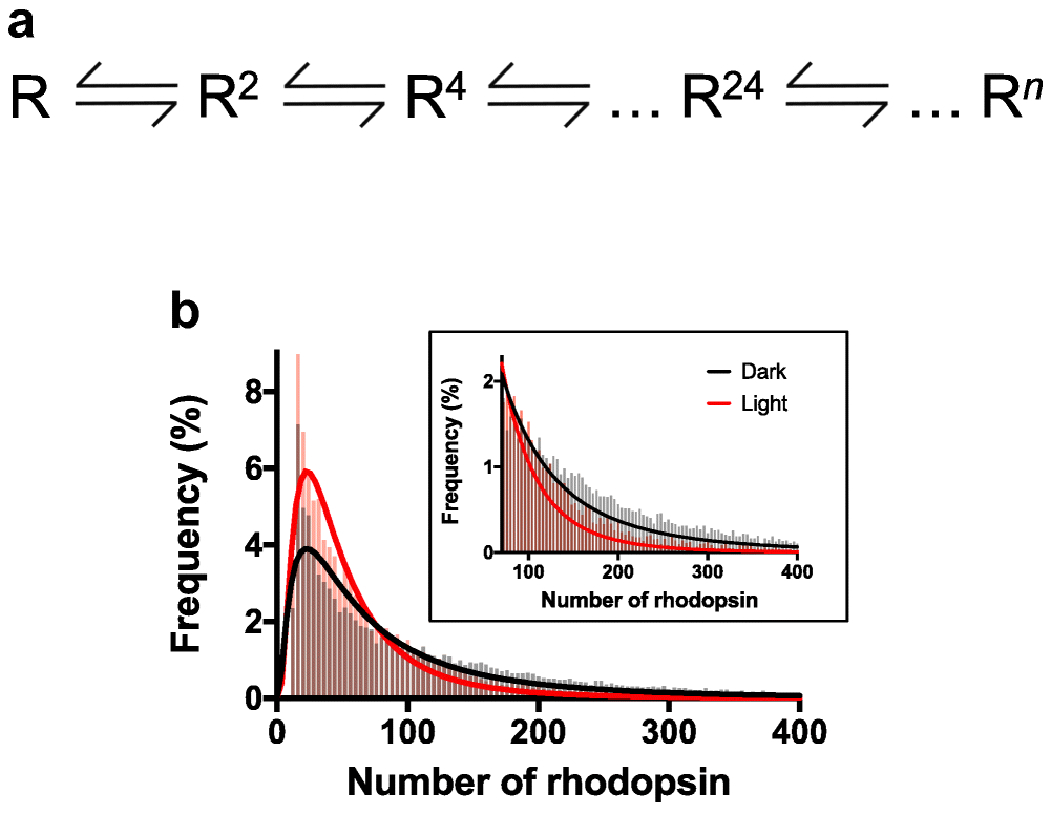

Oligomerization of rhodopsin within ROS disc membranes appears to proceed according to descriptions based on chemical equilibria [106] (Fig. 5A). Such descriptions predict the presence of an equilibrium of different sized oligomers of rhodopsin that can interconvert. Consistent with these predictions, AFM studies revealed a log Gaussian distribution of rhodopsin nanodomain/oligomer sizes present in ROS disc membranes with a predominant oligomeric size of about a 24-mer [115,116,128,149] (e.g., Fig. 5B). In heterologous expression systems, where the expression of rhodopsin is much lower compared to that in rod photoreceptor cells, a monomer-dimer and dimer-tetramer equilibria have been detected and the equilibrium constants defined [29,90]. The defined equilibrium constants indicate that at concentrations of rhodopsin present in ROS disc membranes, little or no tetramers or smaller oligomeric forms are expected to be present, which is consistent with the AFM data (Fig. 5B). The interconversion of oligomeric forms of rhodopsin has yet to be demonstrated by AFM, and may be impeded by adsorption of the membrane samples on a solid mica surface. An interconversion of oligomeric forms of rhodopsin is indicated in TIRF microscopy studies on fragmented ROS fluorescently labeled with a Fab fragment of an anti-rhodopsin antibody [54], where the sizes of rhodopsin clusters were shown to change over time.

Figure 5.

Distribution of rhodopsin oligomeric forms. A. A chemical equilibria description of rhodopsin oligomerization. Rhodopsin (R) forms oligomers of various sizes (denoted by superscript). The concentration of rhodopsin and the equilibrium constants will dictate the complement of oligomeric forms of rhodopsin present in the membrane. B. Histogram of different sizes of rhodopsin oligomers detected by AFM in native ROS disc membranes. Data showing the distribution of nanodomain sizes in [115] was converted to the number of rhodopsin molecules in an oligomeric complex by presuming each rhodopsin molecule occupies 14 nm2 of space, as described previously in [149]. The distribution of rhodopsin oligomeric sizes in ROS disc membranes is shown for mice housed under constant dark (black) or constant light (red) conditions for 10 days. The inset shows a zoomed in view of the histogram for oligomeric sizes greater than 70 rhodopsin molecules. The histograms were fit with a log Gaussian function.

If oligomerization of rhodopsin proceeds via a mechanism based on chemical equilibria, the complement of oligomeric forms present in the ROS disc membrane will be dictated by the concentration of rhodopsin in the membrane and the equilibrium constants. Concentration-dependent oligomerization has been demonstrated in both heterologous expression systems and native rod photoreceptor cells [90,115], where larger oligomeric forms of rhodopsin are detected at higher concentrations of the receptor. The concentration of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes appears to be similar in photoreceptor cells of vertebrate species [114,116,149]. In mice, the density of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes under normal cyclic lighting conditions is about 20,000 μm−2 [115,127]. Adaptive mechanisms are present in rod photoreceptor cells that maintain this concentration of rhodopsin in the membrane, even when the expression of rhodopsin is reduced [114]. One mechanism used by rod photoreceptors to maintain this steady-state concentration of rhodopsin is to change the size of the ROS disc [149].

The concentration of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes can be modulated to a certain extent by changes in the lighting environment of the animal, changes in the signaling capacity of rod photoreceptor cells, or in a diseased state [115,126,127]. The concentration of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes can be modulated by photostasis-related effects where constant light conditions reduce rhodopsin density and constant dark conditions increase rhodopsin density [115]. A 1.8-fold difference in rhodopsin density in the ROS disc membrane is detected in these two extreme lighting conditions. Subtle changes in the complement of oligomeric forms of rhodopsin as a result of this difference in rhodopsin concentration are evident in histograms of rhodopsin oligomeric forms derived from AFM data (Fig. 5B). While the predominant oligomeric species of a 24-mer does not change, as indicated by similar peak positions in histograms, the relative proportion of smaller and very large oligomers is changed (Fig. 5B). Under constant dark conditions where the concentration of rhodopsin is higher, there are more very large oligomers and less smaller oligomers as compared to that under constant light conditions where the concentration of rhodopsin is lower. While there is clear evidence for changes in oligomeric status due to the concentration of rhodopsin in the membrane, more work is required to better understand the factors that contribute to the equilibrium constants defining the various equilibria.

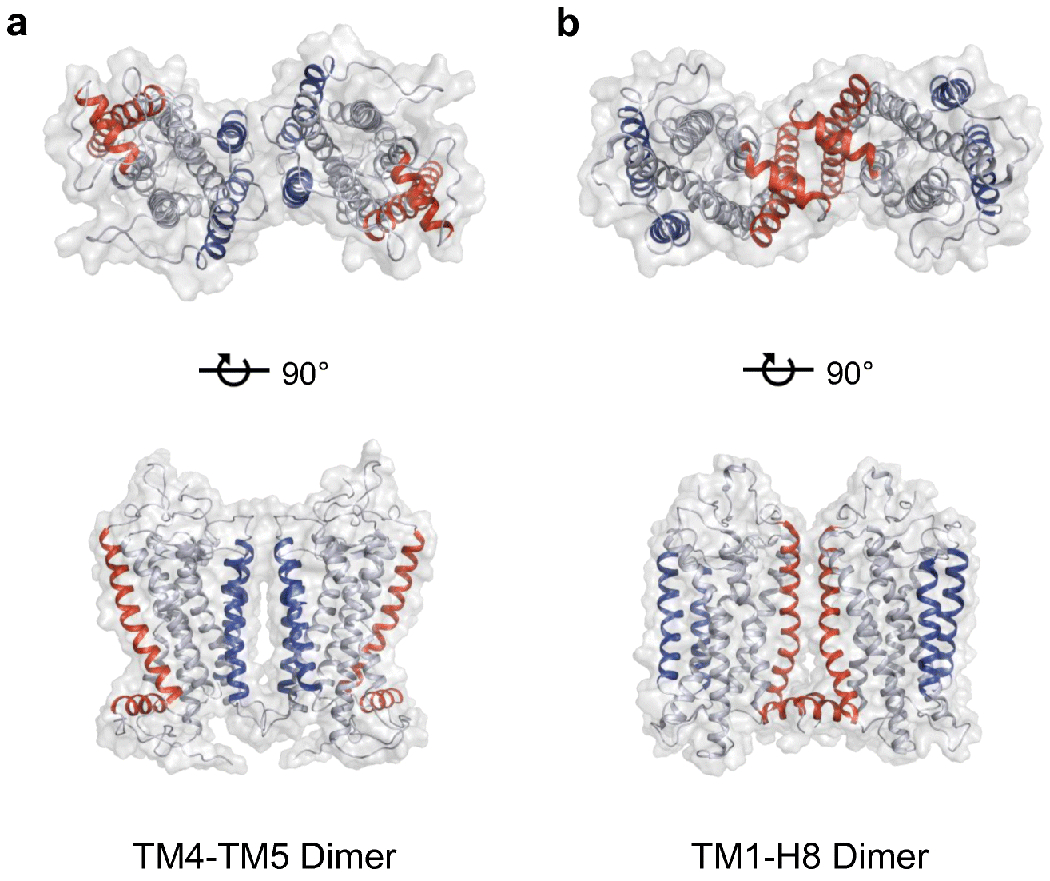

The rhodopsin dimer appears to be a functional unit, where a rhodopsin dimer can engage a single transducin or arrestin molecule [63,91]. Rhodopsin dimers can form rows by combining with other dimers and rhodopsin dimer rows can form in parallel with other rows of dimers (Fig. 4). All the different interfaces within such an oligomeric complex has yet to be fully defined. There are currently two main dimer interfaces that have been proposed for the rhodopsin dimeric unit. The first proposed dimer interface came from a computational model derived from the geometric constraints of rhodopsin molecules visualized in AFM images of ROS disc membranes [43,76]. In this model, the dimer interface is formed by transmembrane helix 4 (TM4) and transmembrane helix 5 (TM5) (Fig. 6A). The rows of dimers are formed by interactions between cytoplasmic loop 1 in one rhodopsin with cytoplasmic loop 3 of the contacting rhodopsin. Parallel rows of dimers involve interactions between residues in TM 1 of each rhodopsin. A low-resolution contour map obtained by single-particle EM of a rhodopsin dimer in complex with transducin was consistent with the TM4-TM5 dimer model [63]. The TM4-TM5 dimeric interface is also supported by in vitro peptide competition and chemical cross-linking studies [58,70].

Figure 6.

Rhodopsin dimer structures. A. Rhodopsin dimer structure derived from AFM data [76](PDB: 1N3M). B. A cryo-EM rhodopsin dimer structure [157](PDB: 6OFJ). TM4 and TM5 are colored blue and TM1 and H8 are colored red.

An alternate rhodopsin dimer interface has been more recently proposed and involves TM1 and H8 (Fig. 6B). This interface has been resolved in a cryo-EM structure of chemically cross-linked rhodopsin extracted from bovine ROS disc membranes and incorporated into nanodiscs [157]. Several lines of evidence are in support of this dimer interface. The TM1-H8 dimer interface is consistent with a chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry study of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes [69]. This interface is also observed in several EM and X-ray crystal structures of rhodopsin [27,104,119,121,124]. Computational studies indicate that the TM1-H8 dimer interface is the most stable dimer interface and that dimers formed with this interface, but not those with the TM4-TM5 interface, can form rows as observed by AFM and cryo-ET [65,109]. Lastly, as described earlier, peptides corresponding to TM1 and H8 appear to disrupt rhodopsin oligomers in vivo [156]. While more work still needs to be done to better define the dimer interface, there currently appears to be more evidence in favor of the TM1-H8 interface as the main dimeric interface.

Membrane proteins like rhodopsin are embedded in a lipid bilayer and it is no surprise that the lipid composition can impact the oligomerization of these hydrophobic proteins [51]. The structure and function of rhodopsin can be modulated by the lipid composition of the membrane [97,98,139,140,146]. Lipids in the membrane also appear to be a driving force in promoting rhodopsin oligomerization and stabilizing these quaternary structures [17,59,108,141]. The interplay between specific lipids and the oligomerization of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes is still unclear.

There are indications that lipid rafts may play a role in the oligomerization of rhodopsin. Lipid rafts are nanoscale domains in the membrane with unique lipid composition enriched in saturated fatty acids and cholesterol [79,110,133]. Lipid rafts appear to be present within the ROS disc membranes and are predicted to be involved in organizing signal transduction [13,84,93,107,130,132,145]. The lipid rafts detected in ROS membranes most often have been isolated and studied as detergent-resistant membranes and therefore it is unclear whether or not the nanodomains containing oligomeric rhodopsin observed by AFM are equivalent to these biochemically isolated lipid rafts. In vitro studies suggest that monomeric rhodopsin is raftophobic whereas dimeric rhodopsin is raftophilic [112,131,143]. Computational studies indicate that lipid rafts can promote the row-like structure of dimeric rhodopsin observed by AFM and cryo-ET [65]. Lipid rafts do not appear to be a requirement for the formation of rhodopsin nanodomains and oligomers, however, since this organization can still exist in the absence of lipid rafts [54]. More work is required to better understand the role lipids and lipid rafts play in the observed supramolecular organization of rhodopsin within ROS disc membranes.

Why is a supramolecular organization of rhodopsin necessary?

Although the experimental evidence points to a supramolecular organization of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes in photoreceptor cells, a clear-cut advantage for this organization has yet to be demonstrated experimentally. For instance, if the formation of oligomers was a requisite for function of the receptor or if disruption of rhodopsin oligomerization were demonstrated to cause dysfunction and disease, then it would be clear why rhodopsin must adopt a quaternary structure. The evidence so far indicates that neither of these scenarios are true for rhodopsin. In vitro functional and structural studies demonstrate that a single rhodopsin molecule is sufficient to engage and form functional complexes with signaling molecules such as transducin, arrestin, and rhodopsin kinase [3,5,6,38,44,52,66,144,150,158]. Thus, monomeric rhodopsin retains the ability to carry out the basic signaling function of the receptor (Fig 2).

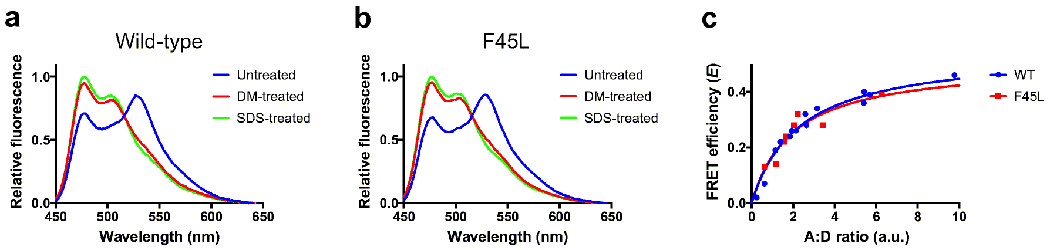

A role for rhodopsin oligomerization in maintaining the health of rod photoreceptor cells was indicated in an initial biochemical study on three mutations in rhodopsin, F45L, V209M and F220C, which were thought to cause retinitis pigmentosa [111]. The mutant rhodopsins were heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells, extracted in detergent and then reconstituted into lipid vesicles. Inferences from the scramblase activity of reconstituted rhodopsin appeared to indicate that the mutations disrupt rhodopsin dimerization. Subsequent studies examining the oligomeric status of these mutations in the membrane of cells contradicted these findings. Chemical cross-linking, fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy, and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer demonstrated that the V209M and F220C rhodopsin mutants heterologously expressed in HEK239 cells form oligomers similarly as wild-type rhodopsin [82]. Our own unpublished data utilizing FRET on the F45L rhodopsin mutant heterologously expressed in HEK239 cells also indicates that this mutation forms oligomers similar to the wild-type receptor (Fig. 7). Knockin mice expressing the F45L or F220C mutant rhodopsins do not display any significant pathology suggesting that these mutations may not in fact cause retinitis pigmentosa [75]. Thus, the F45L, V209M and F220C mutations do not appear to disrupt rhodopsin oligomerization within the membrane and may not even cause retinitis pigmentosa. Furthermore, the discrepancy in observations made in in vitro reconstituted vesicles and in the membrane of cells indicates that the factors driving oligomerization in vesicles have differences compared to those in living cells. This difference further highlights the point raised earlier that observations under in vitro conditions must be interpreted with care.

Figure 7.

FRET analysis of wild-type (WT) and F45L mutant rhodopsin. FRET experiments were conducted in HEK293 cells coexpressing mTurquoise2 (mTq2)- and yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-tagged human WT rhodopsin or mTq2- and YFP-tagged human F45L mutant rhodopsin, as described previously [48]. DNA constructs for WT rhodopsin are described in [47]. The F45L mutation was introduced into the sequence for WT rhodopsin adapting procedures in the QuickChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), as described previously for other point mutations [47]. A, B. Fluorescence emission spectra were collected after excitation at 425 nm of cells coexpressing mTq2- and YFP-tagged WT rhodopsin (A) or mTq2- and YFP-tagged F45L mutant rhodopsin (B). Fluorescence emission spectra were obtained from untreated cells, cells treated with 1.3 mM n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DM) for 5 minutes and then 3.3 mM SDS for 5 minutes. The FRET efficiency (E) was computed by measuring the dequenching of fluorescence emission from mTq2 at 476 nm (Em476). DM-sensitive FRET, which corresponds to rhodopsin oligomers [48], was computed as follows: E = (Em476DM-treated – Em476untreated))/Em476SDS-treated. The example spectra were obtained at an acceptor (YFP) to donor (mTq2) ratio (A:D ratio) of 2. C. DM-sensitive FRET efficiencies were computed at different A:D ratios to generate FRET curves. The data were fit by non-linear regression to a rectangular hyperbolic function using Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). FRET curves for WT and F45L mutant rhodopsin were similar, indicating both forms of the receptor similarly form oligomers.

What then is the advantage afforded by attaining a supramolecular structure and what purpose does this serve for the function of rod photoreceptor cells? The role of rod photoreceptor cells in scotopic vision requires function under environments that are relatively scarce in the number of photons of light. Accordingly, rod photoreceptor cells exhibit exquisite sensitivity, capable of generating a response to activation by a single photon of light [8,55]. To facilitate this exquisite sensitivity, the tertiary structure of rhodopsin is engineered to maintain an inactive state in the dark, limiting spontaneous activation of the receptor, and to provide a protein environment that allows the isomerization of 11-cis retinal to proceed with high quantum yield [105]. Moreover, rhodopsin is packed into the ROS disc membrane at an extremely high density to maximize the probability of photon capture. The observed density of 20,000 μm−2 for rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes is several orders of magnitude higher than that of other typical GPCRs in their native membranes, with density estimates of 5-30 μm−2 [49,56,57,115,127].

The high density of rhodopsin can be beneficial in one aspect of achieving sensitivity in signaling, however, it can present a challenge in another aspect. The high density of rhodopsin results in a crowded membrane environment in which the diffusion-mediated events in phototransduction must occur, which would impede the efficiency of signaling. Moreover, the high density of rhodopsin in the ROS may lead to toxicity under certain circumstances since the release of all-trans retinal after light activation can be toxic for photoreceptor cells if clearance is impaired or overloaded [25,68,80,85]. Thus, there are seemingly opposing factors that rhodopsin must balance in order to carry out its function in rod photoreceptor cells. The observed supramolecular organization of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes appears to reconcile these opposing factors to allow rod photoreceptors to accomplish their role.

In the most simplistic view of rhodopsin signaling, one can imagine the receptor as a mere binary system that is either on or off. Monomeric rhodopsin itself appears to be sufficient to carry out this simplistic task. The function of rhodopsin in rod photoreceptor cells, however, is multidimensional and a simple binary system may not suffice. Oligomeric rhodopsin allows for allosteric interactions among the different molecules of rhodopsin, which provide additional levels of regulation in the activity of the receptor compared to that achievable in a simplistic binary system [153]. Structures of both monomeric and dimeric rhodopsin in complex with transducin and monomeric rhodopsin in complex with arrestin have been determined experimentally [44,63,64,66,158]. A structure of dimeric rhodopsin in complex with arrestin has been determined computationally [91]. These structures demonstrate that both monomeric and dimeric rhodopsin can engage signaling partners, however, only the dimeric form can exhibit allosteric interactions, which can lead to more complex modes of action. Allosteric interactions have been demonstrated to occur between rhodopsin molecules in a dimeric unit both computationally and experimentally [9,40,61,95,138].

The allosteric interactions within a dimeric unit may serve multiple purposes that include efficiency in signaling as well as protecting the photoreceptor cell. Functional asymmetry has been observed within individual rhodopsin molecules in a purified complex of a rhodopsin dimer and a single transducin heterotrimer [61]. When the rhodopsin dimer is activated by light and bound to transducin, one rhodopsin molecule remains in the activated state bound to all-trans retinal whereas the other rhodopsin molecule goes through the typical life cycle ending in the release of all-trans retinal (Fig. 2). The free opsin molecule can be regenerated with chromophore whereas the other rhodopsin molecule within the dimer locked in the active state remains in this state until transducin is released. While these studies illustrate the allosteric interactions between rhodopsin molecules and the modulation by transducin, indicating a role in signaling, the precise interplay of these allosteric interactions and how they contribute to the signaling process must still be investigated further.

Similar to transducin, arrestin also appears to promote allosteric interactions between rhodopsin molecules in a dimeric unit. Spectroscopy studies in ROS disc membrane samples reveal that a single arrestin molecule can bind dimeric rhodopsin, and that within this complex, arrestin stabilizes the activated state in one rhodopsin molecule that remains bound to all-trans retinal whereas the other rhodopsin molecule after release of all-trans retinal is locked in an inactive state [9,138]. Interestingly, the engagement of a single arrestin molecule with dimeric rhodopsin appears to occur only at higher lighting intensities whereas a single arrestin molecule engages with a single rhodopsin molecule at lower lighting intensities [137]. Thus, the engagement of arrestin with dimeric rhodopsin appears to play a protective role in rod photoreceptor cells under bright light conditions such as daily daylight conditions [9,138]. Under those conditions, the allosteric interactions promoted by arrestin would prevent the full release of all-trans retinal from rhodopsin since half the rhodopsin molecules would retain the chromophore while engaged with arrestin. This mechanism would help prevent the build-up of all-trans retinal, which is toxic for photoreceptor cells [25,68,80,85].

The examples given above illustrate how allosteric interactions within a dimeric unit of rhodopsin can contribute to signaling and the protection of rod photoreceptor cells. What role does the higher order organization of rhodopsin within nanodomains play? Several computational studies have been carried out to determine whether or not a supramolecular organization of rhodopsin is consistent with observed experimental observations on function. These studies demonstrate that both monomeric rhodopsin and a nanodomain organization of oligomeric rhodopsin can be consistent with experimental kinetic data describing signaling between rhodopsin and transducin [34,49,125]. However, a clear advantage of the nanodomain organization over the monomeric organization is apparent at densities of the receptor above the 20,000 μm−2 reported for typical conditions [34,117]. As discussed earlier, photostasis effects are observed under constant dark conditions, where the density of rhodopsin in the membrane is increased in response to conditions where photons of light are scarce [115]. Under these conditions of increased rhodopsin density, signaling is predicted to be impeded when in a monomeric arrangement but enhanced when rhodopsin is in a nanodomain organization [34,117,123].

The observed supramolecular organization of rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes may have been engineered for the specific function of rod photoreceptor cells under scotopic conditions and its single photon response capabilities [21,32]. The rows of dimeric rhodopsin that form nanodomains observed in ROS disc membranes provide a platform for the experimentally observed transient complexes formed by rhodopsin and transducin prior to light activation and the positive cooperativity observed in the binding of transducin to rhodopsin in ROS disc membranes [33,147,151]. Computational studies support these experimental observations and further demonstrate that the rows of rhodopsin dimers in nanodomains can act as a kinetic trap for transducin prior to light activation, which may allow for a uniform single photon response [49]. The features inherent to a nanodomain organization appear to overcome the limitations of a purely diffusion-mediated signaling process and allow for reliable signaling under conditions where photons of light are scarce.

Concluding remarks

Rhodopsin has been intensely studied for quite some time and we are therefore fortunate to draw from a large body of work to reconcile the question of how rhodopsin is organized within the membrane of rod photoreceptor cells. Evidence presented in favor of a monomeric arrangement of rhodopsin (Table 1) do not necessarily rule out the existence of oligomeric forms of rhodopsin. In some instances, evidence used in support of monomers may in fact be consistent with the more recent view presented here of oligomeric rhodopsin forming nanodomains. Methods allowing for the visualization of rhodopsin within ROS disc membranes paint a picture of a supramolecular organization consisting of nanodomains of rhodopsin that form parallel rows of dimers (Fig. 4). The determinants and functional role of this supramolecular organization are beginning to emerge, however, there is still much to be investigated and important issues to be resolved. The discussion presented here on these topics hopefully puts to rest some of the controversies related to the observed supramolecular organization of rhodopsin within ROS disc membranes and serves as a springboard for future advancements to better understand rhodopsin and photoreceptor cell structure and function.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Megan Gragg for generating the data shown in Fig. 7. This work was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01EY021731).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Albert AD, Young JE, Paw Z (1998) Phospholipid fatty acyl spatial distribution in bovine rod outer segment disk membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1368:52–60. doi:S0005-2736(97)00200-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews LD, Cohen AI (1979) Freeze-fracture evidence for the presence of cholesterol in particle-free patches of basal disks and the plasma membrane of retinal rod outer segments of mice and frogs. J Cell Biol 81:215–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee S, Huber T, Sakmar TP (2008) Rapid incorporation of functional rhodopsin into nanoscale apolipoprotein bound bilayer (NABB) particles. J Mol Biol 377:1067–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baroin A, Thomas DD, Osborne B, Devaux PF (1977) Saturation transfer electron paramagnetic resonance on membrane-bound proteins. I-Rotational diffusion of rhodopsin in the visual receptor membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 78:442–447. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)91274-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayburt TH, Leitz AJ, Xie G, Oprian DD, Sligar SG (2007) Transducin activation by nanoscale lipid bilayers containing one and two rhodopsins. J Biol Chem 282:14875–14881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701433200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayburt TH, Vishnivetskiy SA, McLean MA, Morizumi T, Huang CC, Tesmer JJ, Ernst OP, Sligar SG, Gurevich VV (2011) Monomeric rhodopsin is sufficient for normal rhodopsin kinase (GRK1) phosphorylation and arrestin-1 binding. J Biol Chem 286:1420–1428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baylor DA, Lamb TD (1982) Local effects of bleaching in retinal rods of the toad. J Physiol 328:49–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baylor DA, Lamb TD, Yau KW (1979) Responses of retinal rods to single photons. J Physiol 288:613–634 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyriere F, Sommer ME, Szczepek M, Bartl FJ, Hofmann KP, Heck M, Ritter E (2015) Formation and decay of the arrestin.rhodopsin complex in native disc membranes. J Biol Chem 290:12919–12928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.620898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blasie JK, Worthington CR (1969) Molecular localization of frog retinal receptor photopigment by electron microscopy and low-angle X-ray diffraction. J Mol Biol 39:407–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blasie JK, Worthington CR (1969) Planar liquid-like arrangement of photopigment molecules in frog retinal receptor disk membranes. J Mol Biol 39:417–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blaurock AE, Stoeckenius W (1971) Structure of the purple membrane. Nat New Biol 233:152–155. doi: 10.1038/newbio233152a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boesze-Battaglia K, Dispoto J, Kahoe MA (2002) Association of a photoreceptor-specific tetraspanin protein, ROM-1, with triton X-100-resistant membrane rafts from rod outer segment disk membranes. J Biol Chem 277:41843–41849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207111200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boesze-Battaglia K, Fliesler SJ, Albert AD (1990) Relationship of cholesterol content to spatial distribution and age of disc membranes in retinal rod outer segments. J Biol Chem 265:18867–18870 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boll F (1977) On the anatomy and physiology of the retina. Vision Res 17:1249–1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borochov-Neori H, Fortes PA, Montal M (1983) Rhodopsin in reconstituted phospholipid vesicles. 2. Rhodopsin-rhodopsin interactions detected by resonance energy transfer. Biochemistry 22:206–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Botelho AV, Huber T, Sakmar TP, Brown MF (2006) Curvature and hydrophobic forces drive oligomerization and modulate activity of rhodopsin in membranes. Biophys J 91:4464–4477. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brett M, Findlay JB (1979) Investigation of the organization of rhodopsin in the sheep photoreceptor membrane by using cross-linking reagents. Biochem J 177:215–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buzhynskyy N, Salesse C, Scheuring S (2011) Rhodopsin is spatially heterogeneously distributed in rod outer segment disk membranes. J Mol Recognit 24:483–489. doi: 10.1002/jmr.1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caldwell RB, McLaughlin BJ (1985) Freeze-fracture study of filipin binding in photoreceptor outer segments and pigment epithelium of dystrophic and normal retinas. J Comp Neurol 236:523–537. doi: 10.1002/cne.902360408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cangiano L, Dell’Orco D (2013) Detecting single photons: a supramolecular matter? FEBS Lett 587:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chabre M (1975) X-ray diffraction studies of retinal rods. I. Structure of the disc membrane, effect of illumination. Biochim Biophys Acta 382:322–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chabre M, Cone R, Saibil H (2003) Biophysics: is rhodopsin dimeric in native retinal rods? Nature 426:30–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chabre M, le Maire M (2005) Monomeric G-protein-coupled receptor as a functional unit. Biochemistry 44:9395–9403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y, Okano K, Maeda T, Chauhan V, Golczak M, Maeda A, Palczewski K (2012) Mechanism of all-trans-retinal toxicity with implications for stargardt disease and age-related macular degeneration. J Biol Chem 287:5059–5069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.315432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YS, Hubbell WL (1973) Temperature- and light-dependent structural changes in rhodopsin-lipid membranes. Exp Eye Res 17:517–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choe HW, Kim YJ, Park JH, Morizumi T, Pai EF, Krauss N, Hofmann KP, Scheerer P, Ernst OP (2011) Crystal structure of metarhodopsin II. Nature 471:651–655. doi: 10.1038/nature09789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cicuta P, Keller SL, Veatch SL (2007) Diffusion of liquid domains in lipid bilayer membranes. J Phys Chem B 111:3328–3331. doi: 10.1021/jp0702088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comar WD, Schubert SM, Jastrzebska B, Palczewski K, Smith AW (2014) Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy measures clustering and mobility of a G protein-coupled receptor opsin in live cell membranes. J Am Chem Soc 136:8342–8349. doi: 10.1021/ja501948w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cone RA (1972) Rotational diffusion of rhodopsin in the visual receptor membrane. Nature New Biology 236:39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corless JM, Cobbs WH 3rd, Costello MJ, Robertson JD (1976) On the asymmetry of frog retinal rod outer segment disk membranes. Exp Eye Res 23:295–324. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(76)90130-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dell’Orco D (2013) A physiological role for the supramolecular organization of rhodopsin and transducin in rod photoreceptors. FEBS Lett 587:2060–2066. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dell’Orco D, Koch KW (2011) A dynamic scaffolding mechanism for rhodopsin and transducin interaction in vertebrate vision. Biochem J 440:263–271. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dell’Orco D, Schmidt H (2008) Mesoscopic Monte Carlo simulations of stochastic encounters between photoactivated rhodopsin and transducin in disc membranes. J Phys Chem B 112:4419–4426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Downer NW (1985) Cross-linking of dark-adapted frog photoreceptor disk membranes. Evidence for monomeric rhodopsin. Biophys J 47:285–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Downer NW, Cone RA (1985) Transient dichroism in photoreceptor membranes indicates that stable oligomers of rhodopsin do not form during excitation. Biophys J 47:277–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edrington TCt, Bennett M, Albert AD (2008) Calorimetric studies of bovine rod outer segment disk membranes support a monomeric unit for both rhodopsin and opsin. Biophys J 95:2859–2866. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.128868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ernst OP, Gramse V, Kolbe M, Hofmann KP, Heck M (2007) Monomeric G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin in solution activates its G protein transducin at the diffusion limit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:10859–10864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701967104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feldman TB, Ivankov OI, Kuklin AI, Murugova TN, Yakovleva MA, Smitienko OA, Kolchugina IB, Round A, Gordeliy VI, Belushkin AV, Ostrovsky MA (2019) Small-angle neutron and X-ray scattering analysis of the supramolecular organization of rhodopsin in photoreceptor membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1861:183000. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2019.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Filizola M, Wang SX, Weinstein H (2006) Dynamic models of G-protein coupled receptor dimers: indications of asymmetry in the rhodopsin dimer from molecular dynamics simulations in a POPC bilayer. J Comput Aided Mol Des 20:405–416. doi: 10.1007/s10822-006-9053-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fisher KA, Stoeckenius W (1977) Freeze-fractured purple membrane particles: protein content. Science 197:72–74. doi: 10.1126/science.867052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fotiadis D, Liang Y, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Engel A, Palczewski K (2003) Atomic-force microscopy: Rhodopsin dimers in native disc membranes. Nature 421:127–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fotiadis D, Liang Y, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Engel A, Palczewski K (2004) The G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin in the native membrane. FEBS Lett 564:281–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao Y, Hu H, Ramachandran S, Erickson JW, Cerione RA, Skiniotis G (2019) Structures of the Rhodopsin-Transducin Complex: Insights into G-Protein Activation. Mol Cell 75:781–790 e783. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Govardovskii VI, Korenyak DA, Shukolyukov SA, Zueva LV (2009) Lateral diffusion of rhodopsin in photoreceptor membrane: a reappraisal. Mol Vis 15:1717–1729 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gragg M, Kim TG, Howell S, Park PS (2016) Wild-type opsin does not aggregate with a misfolded opsin mutant. Biochim Biophys Acta 1858:1850–1859. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gragg M, Park PS (2018) Misfolded rhodopsin mutants display variable aggregation properties. Biochim Biophys Acta 1864:2938–2948. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gragg M, Park PS (2019) Detection of misfolded rhodopsin aggregates in cells by Forster resonance energy transfer. Methods Cell Biol 149:87–105. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gunkel M, Schoneberg J, Alkhaldi W, Irsen S, Noe F, Kaupp UB, Al-Amoudi A (2015) Higher-order architecture of rhodopsin in intact photoreceptors and its implication for phototransduction kinetics. Structure 23:628–638. doi : 10.1016/j.str.2015.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gupta BD, Williams TP (1990) Lateral diffusion of visual pigments in toad (Bufo marinus) rods and in catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) cones. J Physiol 430:483–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gupta K, Donlan JAC, Hopper JTS, Uzdavinys P, Landreh M, Struwe WB, Drew D, Baldwin AJ, Stansfeld PJ, Robinson CV (2017) The role of interfacial lipids in stabilizing membrane protein oligomers. Nature 541:421–424. doi: 10.1038/nature20820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanson SM, Gurevich EV, Vishnivetskiy SA, Ahmed MR, Song X, Gurevich VV (2007) Each rhodopsin molecule binds its own arrestin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:3125–3128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610886104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hargrave PA, McDowell JH, Curtis DR, Wang JK, Juszczak E, Fong SL, Rao JK, Argos P (1983) The structure of bovine rhodopsin. Biophys Struct Mech 9:235–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayashi F, Saito N, Tanimoto Y, Okada K, Morigaki K, Seno K, Maekawa S (2019) Raftophilic rhodopsin-clusters offer stochastic platforms for G protein signalling in retinal discs. Commun Biol 2:209. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0459-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hecht S, Shlaer S, Pirenne MH (1942) Energy, Quanta, and Vision. J Gen Physiol 25:819–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hegener O, Prenner L, Runkel F, Baader SL, Kappler J, Haberlein H (2004) Dynamics of beta2-adrenergic receptor-ligand complexes on living cells. Biochemistry 43:6190–6199. doi: 10.1021/bi035928t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herrick-Davis K, Grinde E, Lindsley T, Teitler M, Mancia F, Cowan A, Mazurkiewicz JE (2015) Native serotonin 5-HT2C receptors are expressed as homodimers on the apical surface of choroid plexus epithelial cells. Mol Pharmacol 87:660–673. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.096636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jastrzebska B, Chen Y, Orban T, Jin H, Hofmann L, Palczewski K (2015) Disruption of Rhodopsin Dimerization with Synthetic Peptides Targeting an Interaction Interface. J Biol Chem 290:25728–25744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.662684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jastrzebska B, Fotiadis D, Jang GF, Stenkamp RE, Engel A, Palczewski K (2006) Functional and structural characterization of rhodopsin oligomers. J Biol Chem 281:11917–11922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jastrzebska B, Maeda T, Zhu L, Fotiadis D, Filipek S, Engel A, Stenkamp RE, Palczewski K (2004) Functional characterization of rhodopsin monomers and dimers in detergents. J Biol Chem 279:54663–54675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jastrzebska B, Orban T, Golczak M, Engel A, Palczewski K (2013) Asymmetry of the rhodopsin dimer in complex with transducin. FASEB J 27:1572–1584. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-225383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jastrzebska B, Ortega JT, Park PSH (2020) Chapter 5 - Supramolecular structure of opsins. In: Jastrzebska B, Park PSH(eds) GPCRs. Academic Press, pp 81–95. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-816228-6.00005-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jastrzebska B, Ringler P, Lodowski DT, Moiseenkova-Bell V, Golczak M, Muller SA, Palczewski K, Engel A (2011) Rhodopsin-transducin heteropentamer: three-dimensional structure and biochemical characterization. J Struct Biol 176:387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jastrzebska B, Ringler P, Palczewski K, Engel A (2013) The rhodopsin-transducin complex houses two distinct rhodopsin molecules. J Struct Biol 182:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaneshige Y, Hayashi F, Morigaki K, Tanimoto Y, Yamashita H, Fujii M, Awazu A (2020) Affinity of rhodopsin to raft enables the aligned oligomer formation from dimers: Coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulation of disk membranes. PLoS ONE 15:e0226123. doi : 10.1371/journal.pone.0226123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kang Y, Zhou XE, Gao X, He Y, Liu W, Ishchenko A, Barty A, White TA, Yefanov O, Han GW, Xu Q, de Waal PW, Ke J, Tan MH, Zhang C, Moeller A, West GM, Pascal BD, Van Eps N, Caro LN, Vishnivetskiy SA, Lee RJ, Suino-Powell KM, Gu X, Pal K, Ma J, Zhi X, Boutet S, Williams GJ, Messerschmidt M, Gati C, Zatsepin NA, Wang D, James D, Basu S, Roy-Chowdhury S, Conrad CE, Coe J, Liu H, Lisova S, Kupitz C, Grotjohann I, Fromme R, Jiang Y, Tan M, Yang H, Li J, Wang M, Zheng Z, Li D, Howe N, Zhao Y, Standfuss J, Diederichs K, Dong Y, Potter CS, Carragher B, Caffrey M, Jiang H, Chapman HN, Spence JC, Fromme P, Weierstall U, Ernst OP, Katritch V, Gurevich VV, Griffin PR, Hubbell WL, Stevens RC, Cherezov V, Melcher K, Xu HE (2015) Crystal structure of rhodopsin bound to arrestin by femtosecond X-ray laser. Nature 523:561–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khan SM, Bolen W, Hargrave PA, Santoro MM, McDowell JH (1991) Differential scanning calorimetry of bovine rhodopsin in rod-outer-segment disk membranes. Eur J Biochem 200:53–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb21047.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim SR, Jang YP, Jockusch S, Fishkin NE, Turro NJ, Sparrow JR (2007) The all-trans-retinal dimer series of lipofuscin pigments in retinal pigment epithelial cells in a recessive Stargardt disease model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:19273–19278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708714104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Knepp AM, Periole X, Marrink SJ, Sakmar TP, Huber T (2012) Rhodopsin forms a dimer with cytoplasmic helix 8 contacts in native membranes. Biochemistry 51:1819–1821. doi: 10.1021/bi3001598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kota P, Reeves PJ, Rajbhandary UL, Khorana HG (2006) Opsin is present as dimers in COS1 cells: Identification of amino acids at the dimeric interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Krebs W, Kuhn H (1977) Structure of isolated bovine rod outer segment membranes. Exp Eye Res 25:511–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kuhne W (1977) Chemical processes in the retina. Vision Res 17:1269–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kusumi A, Hyde JS (1982) Spin-label saturation-transfer electron spin resonance detection of transient association of rhodopsin in reconstituted membranes. Biochemistry 21:5978–5983. doi: 10.1021/bi00266a039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kusumi A, Ohnishi S, Ito T, Yoshizawa T (1978) Rotational Motion of Rhodopsin in Visual Receptor Membrane as Studied by Saturation Transfer Spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta 507:539–543. doi:Doi 10.1016/0005-2736(78)90362-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lewis TR, Shores CR, Cady MA, Hao Y, Arshavsky VY, Burns ME (2020) The F220C and F45L rhodopsin mutations identified in retinitis pigmentosa patients do not cause pathology in mice. Sci Rep 10:7538. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64437-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liang Y, Fotiadis D, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Palczewski K, Engel A (2003) Organization of the G protein-coupled receptors rhodopsin and opsin in native membranes. J Biol Chem 278:21655–21662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liang Y, Fotiadis D, Maeda T, Maeda A, Modzelewska A, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Engel A, Palczewski K (2004) Rhodopsin signaling and organization in heterozygote rhodopsin knockout mice. J Biol Chem 279:48189–48196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liebman PA, Entine G (1974) Lateral diffusion of visual pigment in photorecptor disk membranes. Science 185:457–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lingwood D, Simons K (2010) Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science 327:46–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1174621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maeda A, Maeda T, Golczak M, Palczewski K (2008) Retinopathy in mice induced by disrupted all-trans-retinal clearance. J Biol Chem 283:26684–26693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804505200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Makino CL, Howard LN, Williams TP (1990) Axial gradients of rhodopsin in light-exposed retinal rods of the toad. J Gen Physiol 96:1199–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mallory DP, Gutierrez E, Pinkevitch M, Klinginsmith C, Comar WD, Roushar FJ, Schlebach JP, Smith AW, Jastrzebska B (2018) The Retinitis Pigmentosa-Linked Mutations in Transmembrane Helix 5 of Rhodopsin Disrupt Cellular Trafficking Regardless of Oligomerization State. Biochemistry 57:5188–5201. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mansoor SE, Palczewski K, Farrens DL (2006) Rhodopsin self-associates in asolectin liposomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:3060–3065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martin RE, Elliott MH, Brush RS, Anderson RE (2005) Detailed characterization of the lipid composition of detergent-resistant membranes from photoreceptor rod outer segment membranes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46:1147–1154. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mata NL, Weng J, Travis GH (2000) Biosynthesis of a major lipofuscin fluorophore in mice and humans with ABCR-mediated retinal and macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:7154–7159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130110497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mazzolini M, Facchetti G, Andolfi L, Proietti Zaccaria R, Tuccio S, Treu J, Altafini C, Di Fabrizio EM, Lazzarino M, Rapp G, Torre V (2015) The phototransduction machinery in the rod outer segment has a strong efficacy gradient. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E2715–2724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423162112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McCaslin DR, Tanford C (1981) Different states of aggregation for unbleached and bleached rhodopsin after isolation in two different detergents. Biochemistry 20:5212–5221. doi: 10.1021/bi00521a018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Medina R, Perdomo D, Bubis J (2004) The hydrodynamic properties of dark- and light-activated states of n-dodecyl beta-D-maltoside-solubilized bovine rhodopsin support the dimeric structure of both conformations. J Biol Chem 279:39565–39573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Medina R, Perdomo D, Moller C, Bubis J (2020) Cross-linking of bovine rhodopsin with sulfosuccinimidyl 4-(N maleimidomethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylate affects its functionality. Biochem J 477:2295–2312. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20200376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mishra AK, Gragg M, Stoneman MR, Biener G, Oliver JA, Miszta P, Filipek S, Raicu V, Park PS (2016) Quaternary structures of opsin in live cells revealed by FRET spectrometry. Biochem J 473:3819–3836. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Modzelewska A, Filipek S, Palczewski K, Park PS (2006) Arrestin interaction with rhodopsin: conceptual models. Cell Biochem Biophys 46:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Molday RS, Hicks D, Molday L (1987) Peripherin. A rim-specific membrane protein of rod outer segment discs. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 28:50–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nair KS, Balasubramanian N, Slepak VZ (2002) Signal-dependent translocation of transducin, RGS9-1-Gbeta5L complex, and arrestin to detergent-resistant membrane rafts in photoreceptors. Curr Biol 12:421–425. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00691-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Najafi M, Haeri M, Knox BE, Schiesser WE, Calvert PD (2012) Impact of signaling microcompartment geometry on GPCR dynamics in live retinal photoreceptors. J Gen Physiol 140:249–266. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Neri M, Vanni S, Tavernelli I, Rothlisberger U (2010) Role of aggregation in rhodopsin signal transduction. Biochemistry 49:4827–4832. doi : 10.1021/bi100478j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nickell S, Park PS, Baumeister W, Palczewski K (2007) Three-dimensional architecture of murine rod outer segments determined by cryoelectron tomography. J Cell Biol 177:917–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Niu SL, Mitchell DC, Lim SY, Wen ZM, Kim HY, Salem N Jr., Litman BJ (2004) Reduced G protein-coupled signaling efficiency in retinal rod outer segments in response to n-3 fatty acid deficiency. J Biol Chem 279:31098–31104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404376200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Niu SL, Mitchell DC, Litman BJ (2002) Manipulation of cholesterol levels in rod disk membranes by methyl-beta-cyclodextrin: effects on receptor activation. J Biol Chem 277:20139–20145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200594200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Olive J, Recouvreur M (1977) Differentiation of retinal rod disc membranes in mice. Exp Eye Res 25:63–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Osborne HB, Sardet C, Helenius A (1974) Bovine rhodopsin: characterization of the complex formed with Triton X-100. Eur J Biochem 44:383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Osborne HB, Sardet C, Michel-Villaz M, Chabre M (1978) Structural study of rhodopsin in detergent micelles by small-angle neutron scattering. J Mol Biol 123:177–206. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90320-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ovchinnikov Yu A (1982) Rhodopsin and bacteriorhodopsin: structure-function relationships. FEBS Lett 148:179–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, Le T I, Teller DC, Okada T, Stenkamp RE, Yamamoto M, Miyano M (2000) Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science 289:739–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]