Abstract

Teacher self-efficacy may reduce the likelihood of burnout through preventing the occurrence of work stress. The study inquiries the relationship between teaching efficacy and burnout, focus on mediation of self-esteem. A sample of 329 Chinese special teachers who teach in the special schools in western China was measured with the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the Rosenberg self-esteem scale and the Self-efficacy scale. Results indicated that emotional exhaustion and depersonalization of Chinese special teachers are at a medium level and personal accomplishment are at a low level. The mediation analysis shows that under the education background of special education, self-esteem plays partial mediation role in general teaching efficacy or personal teaching efficacy and job burnout of special education teachers.

Keywords: teaching efficacy, self-esteem, job-burnout, special education teachers, special schools, China, mediation effect

Introduction

The special education field has been lacking qualifiedteachers for a long time due to various factors. One of the importantfactors affecting teacher attrition is “burnout” that can lead to the teacher to leave the field completely (Wisniewski and Gargiulo 1997, Chang 2009). Burnout usually is conceptualized as a work-related syndrome stemming from the individual’s perception of a significant gap between expectations of successful professional performance and an observed, far less satisfying reality (Schaufeli and Taris 2005). It most usually happens in the people who work in the area needing face to face interaction and needing of support, including education. Researches show that burnout is associated with physical symptoms and depression (Armon et al. 2010, Bianchi et al. 2013). Outcomes associated with teachers’ burnout include teacher attrition, teacher health issues, and negative student outcomes (Brunsting et al. 2014).

Although all of the teachers experience pressure, there is additional stress factors among special education teachers (Shyman 2011, Major 2012). This may be due to the fact special education teachers are faced with a variety of challenges including teaching students with a variety of intellectual levels, physical limitations and emotional or behavioral problems (Emery and Vandenberg 2010). Special education teachers’ work requires intense involvement for students with disabilities which is highly demand of professional knowledge and updating them in the whole career. Supports for students receiving special education services can range from specially designed instruction and accommodations in a single subject area to any combination of academic, behavioral, communication, motor, and nursing needs (Sheldrake 2013). Besides, special education teachers are also faced with a variety of administrative work, including paperwork of individual educational program (Lee et al. 2011). Many studies are conducted in western countries shown that high levels of job burnout among special education teachers (e.g. Embich 2001, Zabel and Kay 2001, Fore et al. 2002, Sloan and LaPlante 2002). Paradoxically, in China most of the research examining occupational stress among special education teachers who work in special schools report medium or low levels of burnout (Liu et al. 2011, Song 2013, Liu and Zhao 2015, Duan 2016).

Special schools was a standard mode of education for the disabled in the history of special education in western developed countries while gradually replaced by the placement of general education classes due to the idea of inclusive education. Even China has been influenced by the philosophy of inclusion as well and there are laws and regulation to require that the students with mild and moderate disabilities should be enrolled in regular schools, there are still 2,152 special schools where 333,480 students with disabilities studying in and 58,700 special education teachers working in Ministry of Education (2019). The daily work and experience of special education teachers in special schools in China is quite different with those in other educational placement in western developed countries where special education teachers mostly work in the general schools. There are separate curricular standard, evaluation, administration and so on for special schools in China. Apart from the different school context, the intensity of special education teachers’ burnout varies from one culture or country to the other. Therefore, the research in China may contribute to complement the studies of the special education teachers’ burnout.

According to the conservation of resources (COR) model (Hobfoll 1989, Hobfoll and Freedy 1993, Hobfoll and Shirom 1993), individuals seek to acquire and maintain resources facing stress, including objects, conditions, personal characteristics, and energies. Personal characteristics are resources which buffer one against stress. Self-esteem and self efficacy are considered to be important personal resource (Rosenberg 1979, Benight et al. 1999). With investigate the relations between teacher self-efficacy, self-esteem and job burnout, this article contributes to reveal what the special education teachers experiences in special schools in China and what’s the influencing mechanism of teacher self-efficacy and self-esteem on job burnout.

Special education teachers’ job-burnout

Burnout, the term was originally proposed to refer to the physically and psychologically burnt for the health-care workers and is generally applied for the human service professionals now (Jennett et al. 2003). Although the definition of burnout is still not unified, the Maslach's multidimensional theory of burnout is widely accepted and cited (Maslach and Jackson 1984, Farber 1991, Díaz et al. 2010) in most empirical work in the area. In this theory, they defined burnout as a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment in the people who need to interact with others. Specifically, emotional exhausting means that the individual’s emotional resources are overextended and depleted. When teacher perceive themselves that they can’t devote themselves to students and teaching as they did earlier, it is the signs of emotional exhaustion (Chang 2009). Depersonalization means the individuals treat other in a negative, callous, or excessively way to others, especially to the recipients. For the teachers, it refers to they develop that attitudes to students, parents, and/or colleagues. Reduced personal accomplishment means the feelings of competence and successful achievement is declined in the career. It exhibits when the teachers feel they are ineffective to accomplish the work, such as teaching and fulfilling other school responsibilities.

The influencing factors of teachers’ job-burnout are various, including school context (e.g. Schaufeli and Bakker 2004, Kokkinos 2007, Liu et al. 2011), challenging student behaviors (Hastings and Brown 2002), personal characteristics (e.g. Anderson and Lwanicki 1984, Judge and Bono 2001, Wu 2010), social support (e.g. Pines 2004, Li 2013, Lynn 2013, Song 2013), paperwork (Billingsley 2004). It is unfortunate those factors are special educators’ daily work (Brunsting et al. 2014). Especially, the teachers in separate special schools do complex work, who are engaged in an increased workload in daily work, including preparation of need-based teaching content and materials, developing and implementing the students’ IEP, intervening students’ problematic behavior, cooperating with the parents of the disabled and other stakeholders et al. The complexities of the situations the teachers work lead to lot more stress and burnout (Reddy 2015).

The impact of teachers’ self efficacy on burnout

Apart from seeking for the external support and effecting factors, the special education teachers as a group with self-group ability, whose positive psychological qualities of themselves can be mined and cultivated for certain to alleviate their burnout. According to the self-concept theory, self-concept has frequently been approached from a cognitive point of view. Mercer (2016) defined self-concept as a complex dynamic system of beliefs, which an individual considers as true with regard to him/herself, each belief having its corresponding value. Teachers’ self-concept has great influence on the teaching-learning process and for the development of students. For the teachers, the teachers’ self-efficacy is one of the most important dimensions of their self-concept which affect their daily work (Ashton 1985, Wheatley 2002). Universally accepted, teaching efficacy can be divided into two dimensions (Bandura 1986): personal teaching efficacy and general teaching efficacy. The formal one is the teachers’ beliefs on the individual ability to impact the student learning; the later one reflects teachers’ beliefs on the power of education whether it can bring change the students’ outcome.

During the last decades the research literature shows a growing interest in the relationship between teaching efficacy and burnout and the moderate or strong relation between them is proved by a pile of researches (e.g. Evers et al. 2002, Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2007, 2010, Schwarzer and Hallum 2008). According to Bandura (2006), teachers’ efficacy can not only influence the general philosophy and values to education, but also their pedagogical practices, such as the goals of actions, how much endeavor they tend to commit, how long they will insist when meeting the difficulties and failures and how much pressure they can withstand.

Further, Bandura (2006) found the mechanism of self-efficacy influencing behavior. It’s said that self-efficacy as a part of self-related cognition which are a major ingredient in the motivation process, can has influence on the motivation level. Teachers with high efficacy tend to make efforts to solve their problems while teachers with low efficacy seem to cope by avoiding dealing with academic problems. Besides, teachers with low efficacy need to expand great energy to relieve their emotional distress and deal with withdrawal, which heightens emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization (Bandura 1997). As a result, the teachers’ self-efficacy works as a personal protection resource factor from the job-burnout (Zheng and Shen 2013). The researches reveal that there are negative relationships between personal teaching efficacy and job-burnout, and the same between the general teaching efficacy and job-burnout as well (Jiang et al. 2007, Schwarzer and Hallum 2008).

The researches on relationship between special education teacher self-efficacy and burnout are in agreement with those of general teachers (Sarıçam and Sakız 2014, Yulianti et al. 2018). Research on self-efficacy may be particularly salient for special educators (Ruble et al. 2013). The special education teachers teaching in separate special schools are on high risk of experiencing low teaching efficacy who need to invest more energy and time comparing with the general education teachers (Awa et al. 2010, Zheng and Shen 2013) and the outcome of students with disabilities is at lower level (Hastings and Brown 2002, Billingsley et al. 2004). An effective way of decreasing burnout among special educators is to enhance their self-efficacy (Sarıçam and Sakız 2014, Cheng 2017, Yulianti et al. 2018).

The impact of self-esteem on burnout

The other variable of self-concept, self-esteem, as described by Rosenberg, which is a positive or negative attitude towards ’Me’, a kind of global assessment of one’s self and is related to social functioning (Kupcewicz 2017). Self-esteem and self-efficacy are related in theoretical and empirical. Individuals who view themselves as efficacious ones tend to have positive images about themselves. While the essential distinction between self-efficacy and self-esteem, lies in these three aspects: (a) self-efficacy implies an internal attribution (the individual is the cause of the behavior), (b) it is prospective, referring to actions in the future, and (c) it is an operative construct (Schwarzer and Hallum 2008).

Affected by the rise of personality study, scholars have advanced that not only self-efficacy, but also self-esteem are vital factors that influence individual variation in motivation, attitudes, and job-burnout (e.g. Gecas and Schwalbe 1983, Judge and Bono 2001). Referring the link between self-esteem and job-burnout, self-consistency theory posits that individuals with high self-esteem are motivated to hold on to high level (Korman 1976, Baumeister et al. 2010). As a result, they make efforts to have good performance on the job. It was recently argued that “it is no secret that the way people feel about themselves affects their work. We have long believed that people who feel good about themselves produce better results” (Hersey and Blanchard 1993). As a type of personality, self-esteem is of great importance in comprehending an individual’s behavior (Brockner 1988).

The literature on the origins of self-esteem (cf. Korman 1971, 1976) suggest that self-esteem has an effect on the individual's effectiveness and ability with the base of his or her own experience. A number of researchers have found that self-esteem is an important element in alleviating burnout (Polok 1990, Ho 2016, Khezerlou 2017). Focusing on burnout as a global construct, the self-esteem was negatively correlated with burnout (Beer and Beer 1992, Friedman and Farber 1992). The particular study on the relationship between self-esteem and burnout for special education teachers is few. Therefore it’s meaningful to explore the impact of self-esteem on special education teachers’ burnout.

The relationship of self-esteem between the self-efficacy and burnout

Besides, there are relationships between the concepts of the self, including self-esteem and self-efficacy (Bandura 1978, Tharenou 1979, Gist 1987, Marsh 1993). The study found that generalized self-efficacy was significantly associated with global self-esteem (r=.51, p<.01), and it follows that “belief in one’s ability to perform is one factor contributing to an individual’s attitude toward oneself” (Sherer et al. 1982, Baumeister et al. 2010). Apart from the discussion on how teacher efficacy and self-esteem have direct effects on teachers’ burnout above. It seems that some of the influence attributed to self-efficacy in previous studies, especially some of the chronic sustained performance and attitude may due to the work of self-esteem. It makes sense that self-esteem partially mediates the influences of self-efficacy on affect and performance (Gardner and Pierce 1998). For the special education teachers, the negative messages they see (like the inefficient of teaching for the disabled) and say to themselves diminish their self-esteem. They begin to feel they too have little worth, which in turn they may begin to make negative evaluation of their work.

Overall, many investigations indicate that the personality factors: self-efficacy and self-esteem bear importantly on teacher burnout (e.g. Bayani and Baghery 2018, Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2010). However, there are some limitations. Firstly, most studies of teachers have focused on a single dimensionality of self-efficacy either personal self-efficacy or general self-efficacy. They are two separate psychological variables and both impact the teachers’ job-burnout (Jiang et al. 2007). Secondly, although there are vast literature on the topic of teacher burnout, most studies tried to investigate the connection separately focusing on either self-efficacy or self-esteem contributing to burnout (Handy 1988) and the systematic empirical research to considerate the relationship of self-efficacy and self-esteem in the influence of teacher burnout is few. Thirdly, there has been few attempt to exam the interrelationship of self-efficacy, self-esteem and job-burnout in the China context where more than 58,700 special education teachers teaching in 2,152 special schools (Ministry of Education 2019), especially for the underdeveloped areas in China.

This paper attempts to address these gaps by trying to exam whether the two dimensions of self-efficacy contribute to the special education teachers’ burnout, which can provide more targeted and comprehensive strategies to improve special education teachers' self-efficacy and reduce job burnout than those focusing on a single dimension. Further we will explore the relationship of job burnout, self-efficacy and self-esteem of special education teachers in order to suggest steps that may be undertaken to ameliorate this problem by mediation hypotheses. According to Shadish (1996), it is useful to utilize the mediation hypotheses to develop and advance theories of human behavior. In addition, they can contribute to the practitioner having an insight into (a) the process and the reason relationships unfold and (b) where in the behavior people having problems, practical interventions need to be taken. Besides, this study is designed to describe the burnout problem among special education teachers within the context of special schools in western China. It’s worthwhile to explore the burnout in that area since it shows the job-burnout of special education teachers is different in areas with different levels of development (Zhang, 2017). China is a developing country with uneven development in various regions, and west of China is undeveloped region, where the development of special education is slow. The GDP of Guangxi ranks 28th out of 31 provinces in mainland China. In 2006, only 61.95% of disabled school-age children in Guangxi were receiving compulsory education in general education or special education schools (Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Disabled Persons' Federation 2007). Therefore, it is very important to explore their burnout level and the key influencing factors of the special education teachers in western China (Peng et al. 2018), since the teachers are the key education resource for the development of special education in western China.

Three questions were addressed in this study.

What’s the status of special education teachers’ job burnout in special schools?

What’s the relationship of special education teachers’ teacher self-efficacy, self-esteem and job burnout?

Does self-esteem act as a mediator between special education teachers’ teacher self-efficacy and job burnout?

Method

Participants and procedure

Data were collected at a training program held in Guangxi normal college which was a province teacher training program on the special education teacher’s knowledge and skills in the summer vacation. Every special school in Guangxi was required to send as least five special education teachers to attend the training program. Method with the questionnaires, the special education teachers in that training program were recruited to complete the survey anonymously and retrieved.

Participants in this study were 329 full-time teachers in special schools, coming from 9 cities of Guangxi province, China. The sample consisted of 89.02% females and 10.98% males. 14.02% of the sample have low teaching experience—up to 3 years of teaching, 28.66% of the participants have 3–8 years of teaching experience, and the rest (57.32%) have the high teaching experience—more than 8 years of teaching.

Measures

Self-esteem

The self-esteem scale developed and validated by Rosenberg (1965) was utilized in this study to measure the self-esteem. The Chinese version of the self-esteem scale was translated and revised by Ji and Yu (1993). It requires participants to indicate the degree on their belief in each of 10 items (e.g. “Overall, I was satisfied with myself”, “I hold a positive attitude with myself”) on a 4-point Likert-type scales, from strongly disagree to strongly agree. There are five questions in the reverse scorecard. The higher the score, the higher the level of self-esteem. The internal consistency coefficient of the test scale was 0.83.

Self-efficacy

There were 27-item in Self-efficacy scale which was developed by Yu et al. (1995), among which 17 items (e.g. “I can solve the learning problems of students in study,” “I can adjust the task according to the student’s level when he meets difficulties in completing a task”) measuring personal teaching effectiveness and 10 items (e.g. “In general, who the students will be is decided by the nature,” “Considering all the factors, the influence of teacher on the students’ development is small”) measuring general teaching effectiveness. There are seven questions in the reverse scorecard. The high score indicated the high level of self-efficacy. For the study, the internal consistency coefficient of personal teaching effectiveness and general teaching effectiveness was 0.86 and 0.79 respectively.

Job-burnout

Job-burnout was measured with the 22-items Maslach Burnout Inventory Educators’ Survey (Maslach et al. 1996, Kokkinos 2006), then translated and revised by Wu et al. (2016) to develop the Chinese version of the job-burnout scale. It contains tripartite: emotional exhaustion (9 items), depersonalization (5 items) and lack of a sense of personal accomplishment (8 items). It asks the respondents to rate the frequency on their experience these feelings on 5-point scale Likert-type scales (daily to never). The higher the score, the higher the level of job-burnout. For the study, the internal consistency coefficient of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment was 0.75, 0.77 and 0.86 respectively.

Data analysis

In the analysis, Over 30% of subjects with missing cases were deleted, regression imputation was adopted for handling other missing data, the valid sample size is 329. Personal and general teaching efficacy, self-esteem and job-burnout are observed variables. The mean of each dimension is taken as the value of each observation variable. To test whether self-esteem plays a mediating role in self-efficacy and job-burnout, the mediation model is applied using the PROCESS SPSS computing tool (Hayes 2012).

Results

Chinese special education teachers’ job-burnout

The first purpose of this study was to assess the level of special education teachers’ burnout in special schools in China. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics. Obviously, there are not high levels of job-burnout in all three dimensions for the participants in this research. Specifically speaking, there exist medium level of stress in the dimensions of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (M = 2.48, SD = 0.52 and M = 1.99, SD = 0.71, respectively), while the low level in the dimension of personal accomplishment (M = 1.88, SD = 0.66).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of job-burnout.

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion | 2.48 | 0.52 |

| Depersonalization | 1.99 | 0.71 |

| Personal accomplishment | 1.88 | 0.66 |

Correlations among job-burnout, self-esteem, and self-efficacy

The study also investigated the relationship among all variables. Calculating the kurtosis and skewness of each variable, the skewness value of each variable is between –0.42 and 0.39, and the kurtosis value is between –0.29 and 0.58. As the kurtosis of the data is small, Pearson correlation was conducted (De Winter et al. 2016) on personal teaching effectiveness, general teaching effectiveness, self-esteem and job-burnout responses. Variables descriptive and correlative statistics present in Table 2.

Table 2.

Variables descriptive and correlative statistics.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Personal teaching effectiveness | 1 | |||

| 2. general teaching effectiveness | .09 | 1 | ||

| 3. Self-esteem | .33*** | .31*** | 1 | |

| 4. Job-burnout | –.32*** | –.27*** | –.47*** | 1 |

| Mean | 3.73 | 3.56 | 3.19 | 2.15 |

| Std. deviation | .43 | .52 | .37 | .50 |

Note. ***p < 0.001. **p < 0.01. *p < 0.05.

As the above table indicates, there was no correlation between personal teaching effectiveness and general teaching effectiveness. There were positive correlations coefficient between personal teaching effectiveness and self-esteem, general teaching effectiveness and self-esteem. Therefore, it can be inferred that the higher the personal teaching effectiveness or the general teaching effectiveness, the higher the self-esteem. Meanwhile, significant negative correlations were reveled between job-burnout and a number of the self-efficacy dimensions, the higher the job-burnout, the lower the personal teaching effectiveness, general teaching effectiveness and self-esteem.

The impact of self-efficacy on the job-burnout: the mediation effect of self-esteem

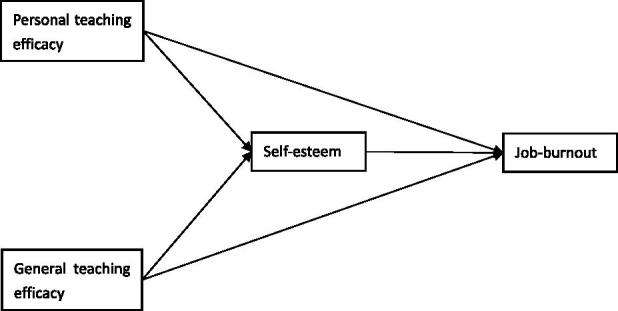

The model shows self-esteem mediates the influence of teaching efficacy, including personal and general teaching efficacy on job-burnout (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Self-esteem as a mediator between two dimensions of teaching efficacy and job-burnout.

First, we tested whether self-esteem plays a mediating role in personal teaching efficacy and job-burnout (see Table 3). The result showed that the model had a direct role on the influence of personal teaching efficacy on job-burnout, and an indirect path from personal teaching efficacy to self-esteem then from self-esteem to job-burnout. The total effect=–0.35, the direct effect=–0.22, the indirect effect=–0.13 and 95% percentile bootstrap confidence intervals = [–0.19, –0.07], this interval does not include 0, indicating that the mediating effect is significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mediation analyses on personal teaching efficacy and job-burnout (2000 bootstraps).

| Independent variable (IV) | Dependent variable (DV) | Mediator (M) | Effect of IV on M |

Effect of M on DV |

Effect of IV on DV |

Direct effect |

Indirect effect |

Total effect |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff | SE | Coeff | SE | Coeff | SE | Coeff | SE | Coeff | 95%CI | Coeff | SE | |||

| Personal teaching efficacy | Job-burnout | Self-esteem | 0.26*** | 0.04 | –0.49*** | 0.07 | –0.22*** | 0.06 | –0.22*** | 0.06 | –0.13 | –0.19, –0.07 | –0.35*** | 0.06 |

Note. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Secondly, we tested self-esteem in mediating the role of general teaching efficacy and job-burnout (see Table 4). The result showed that the model had a direct role on the influence of general teaching efficacy on job-burnout, and an indirect path from general teaching efficacy to self-esteem then from self-esteem to job-burnout. The total effect=–0.23, the direct effect=–0.13, the indirect effect=–0.10, and 95% percentile bootstrap confidence intervals = [–0.14, –0.06], this interval does not include 0, indicating that the mediating effect is significant.

Table 4.

Mediation analyses on general teaching efficacy and job-burnout (2000 bootstraps).

| Independent variable (IV) | Dependent variable (DV) | Mediator (M) | Effect of IV on M |

Effect of M on DV |

Effect of IV on DV |

Direct effect |

Indirect effect |

Total effect |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff | SE | Coeff | SE | Coeff | SE | Coeff | SE | Coeff | 95%CI | Coeff | SE | |||

| General teaching efficacy | Job-burnout | Self-esteem | 0.20*** | 0.04 | –0.49*** | 0.07 | –0.13** | 0.05 | –0.13** | 0.05 | –0.10 | –0.14, –0.06 | –0.23*** | 0.05 |

Note. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Discussion

The present study was carried out in a sample of Chinese special education teachers with the following aims: to evaluate the level of burnout in Chinese special education teachers; to investigate the relationship among all variables (e.g. personal teaching effectiveness, general teaching effectiveness, self-esteem, job-burnout).

Most researchers on teacher burnout has been conducted in North America. This study conducted in west Chinese context provide more information about this topic from an international vision, and extending the previous cross-cultural research in Greek (Platsidou and Agaliotis 2008), Korea (Yuan et al. 2015) and other countries (Schwarzer et al. 2000). It was found that participants of this study did not experience high levels of score in any of the three burnout dimensions. Similar levels of burnout are reported in the Platsidou and Agaliotis (2008) study and the researches on special education teachers in China (Liu et al. 2011, Song 2013, Liu and Zhao 2015). The job-burnout level of Chinese special education teachers was lower than the general education teachers, since the general education teachers were responsible for the enrolment rate of students which was related with their performance assessment (Zhao and Xiao 2009). There are not any ways to evaluate the special education teachers’ performance in China which affect their salary and position. Besides, the special education teachers in authorized size of schools are holding the permanent positions in China. Those seems to relieve the insecurity concerning their work and income, may eliminate the feelings of job-burnout.

Pearson’s correlation revealed that there is a reasonably positive correlation between self-esteem and personal teaching efficacy, which is similar with the work of several researchers (e.g. Korman 1976, Brockner 1988), suggesting that the people with high self-esteem are more likely to have a strong sense of task-based self-efficacy. For teachers, the task-based self-efficacy is the personal teaching efficacy. Pearson correlation also showed a positive correlation between self-esteem and general teaching efficacy. These findings are in line with research addressing the relationship between self-efficacy and self-esteem (Chen et al. 2004, Lane et al. 2004, Zhou 2009). The efficacious action can work as a basis for inner self-esteem (Franks and Marolla 1976, Aealsteinsson et al. 2014). Teachers with high self-efficacy is more likely to use effective teaching practices such as specific efforts and correct methods, to help students with learning difficulties to succeed and to have positive effects on their lives, which is conducive to building a sense of one's own worth, resulting high self-esteem.

Another issue worthy of discussion concerns the finding that there were reasonably negative correlations between job-burnout and the self-concept variables as the correlation analyses presented in Table 2. Significant correlations were obtained for the self-concepts, including special education teachers’ self-efficacy and self-esteem, and the job-burnout. Similar finding are reported in researches (e.g. Benjamin and Black 2012, Sarıçam and Sakız 2014, Chatlos 2016, Reed 2018). The capability of self-direction and self-control in the pursuit of education goals for the students with disabilities are contribute to the high levels of task performance (Gardner and Pierce 1998), which in turn release the job-burnout of special education teachers. The high self-esteem teachers are likely to participate in more task-related activities and to persevere in job performance longer than the teacher with low self-esteem which contribute to the self-worth in job. Besides, teachers’ belief on the power of teaching and the personal teaching ability is more likely to make teachers consist on pursuing education goals for the students by applying various instructional ways and result in the successful work experiences reinforcing self-efficacy, which in turn bring about more successful practices and less job-burnout.

In order to verify whether the proposed interrelationships of general teaching efficacy, personal teaching efficacy, self-esteem and job-burnout hold true, the SEM statistical method were taken. The mediation analysis confirmed the assumptions teachers’ self-esteem works as mediator between self-efficacy and job-burnout. The path are general teaching efficacy and personal teaching efficacy→self-esteem→burnout. How might the mediating effect works between general teaching efficacy and personal teaching efficacy and job-burnout? According to Dembo and Gibson (1985) when met with the students struggling in study with low outcomes, the teacher’s feeling of competence and self-esteem would be protected if he or she thinks the other factors determine the students’ outcome rather than the education, which means the teachers with high general teaching efficacy protect their self-esteem facing frustrating situations. Likewise, feeling of personal teaching efficacy and internal locus of control are critical factors in any educational setting, making the teachers more confident to deal with his/her daily work, which increases the sense of one's own worth and resulting high self-esteem. Special education teachers’ face the various demands of students who have barriers of learning and their work is often seen as a petty or is underestimated (Yulianti et al. 2018). Teachers with high self-esteem try to uphold it by being successful in what they do (Aealsteinsson et al. 2014) and are effective in interpersonal, relationships (Rosse et al. 1991), contributing to their persistence on the challenging work and obtaining external support from colleagues and school leadership, which reduce their burnout.

Some limitations need to be addressed. The sample of participants are not national, it can’t represent the whole picture of the level of job-burnout of special education teachers in China, and a national survey on that area should be conducted in the future studies. Also, considering the job-burnout of special education teachers is not high, coping with the other protector factors would be valuable. Further work should look close at the positive pole of job-burnout to figure out more operable factors to provider more practical implications.

Conclusion

This study illustrate that emotional exhaustion and depersonalization of Chinese special teachers are at a medium level and personal accomplishment are at a low level. The mediation analysis shows that under the education background of special education, self-esteem plays partial mediation role in general teaching efficacy or personal teaching efficacy and job burnout of special education teachers.

The findings in this study help to demonstrate the possible mechanism which protect teachers from perceived job-burnout. Enhancing teachers' optimistic self-confidence, training teaching skills as well as improved self-esteem should be a good precaution to avoid that vicious cycle. Further research should look close at the mechanisms by interventions which can provide the practical strategies.

A statement of ethical process

A formal ethics process was not followed due to the absence of an Ethics Committee process in China in which the study was conducted. In this study, the questionnaires are designed to be anonymous. Moreover before the questionnaires were given to the research participants, we clarified the data was for research purposes only and got their consent.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aealsteinsson, R. I., Frímannsdóttir, I. B. and Konráesson, S.. 2014. Teachers’ self-esteem and self-efficacy. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58(5), 540–550. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M. B. and Lwanicki, E. F.. 1984. Teacher motivation and its relationship to burnout. Educational Administration Quarterly, 20(2), 109–109. [Google Scholar]

- Armon, G., Shirom, A., Melamed, S. and Shapira, I.. 2010. Gender differences in the across-time associations of the job demands-control-support model and depressive symptoms: a three-wave study. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 2(1), 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, P.T.1985. Motivation and the teacher’s sense of efficacy. In: Ames C. & Ames R., eds. Research on motivation in education. Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Awa, W. L., Plaumann, M. and Walter, U.. 2010. Burnout prevention: a review of intervention programs. Patient Education and Counseling, 78(2), 184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.1978. The self system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist, 33(4), 344. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.1986. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory, Prentice-Hall series in social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.1997. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.2006. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In: Pajares F. & Urdan T., eds. Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Greenwich, Connecticut: Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I. and Vohs, K. D.. 2010. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest: A Journal of the American Psychological Society, 4(1), 1–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayani, A. A. and Baghery, H.. 2018. Exploring the influence of self-efficacy, school context and self-esteem on job burnout of Iranian Muslim teachers: a path model approach. Journal of Religion and Health. 10.1007/s10943-018-0703-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer, J. and Beer, J.. 1992. Burnout and stress, depression and self-esteem of teachers. Psychological Reports, 71(3_suppl), 1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, T. and Black, R.. 2012. Resilience theory: risk and protective factors for novice special education teachers. Journal of the American Academy of Special Education Professionals, Spring-Summer, 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Benight, C. C., Ironson, G., Klebe, K., Carver, C. S., Wynings, C., Burnett, K. Greenwood, D., Baum, A., and Schneiderman, N.. 1999. Conservation of resources and coping self-efficacy predicting distress following a natural disaster: a causal model analysis where the environment meets the mind. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 12(2), 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, R., Boffy, C., Hingray, C., Truchot, D. and Laurent, E.. 2013. Comparative symptomatology of burnout and depression. Journal of Health Psychology, 18(6), 782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley, B., Carlson, E. and Klein, S.. 2004. The working conditions and induction support of early career special educators. Exceptional Children, 70(3), 333–347. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley, B. S.2004. Special education teacher retention and attrition: a critical analysis of the research literature. The Journal of Special Education, 38(1), 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Brockner, J.1988. Self-esteem at work: Research, theory, and practice. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brunsting, N. C., Sreckovic, M. A. and Lane, K. L.. 2014. Special education teacher burnout: a synthesis of research from 1979 to 2013. Education and Treatment of Children, 37(4), 681–712. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M. L.2009. An appraisal perspective of teacher burnout: examining the emotional work of teachers. Educational Psychology Review, 21(3), 193–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chatlos, C. N.2016. Special education teachers and autism spectrum disorders: the role of knowledge and self-efficacy on burnout. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global A & I. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M. and Eden, D.. 2004. General self-efficacy and self-esteem: Toward theoretical and empirical distinction between correlated self-evaluations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 375–395. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.2017. Research on the current situation and relationship of job burnout, teaching efficacy and turnover intention of special education teachers. Master Degree Dissertation, Fujian: Fujian Normal University. [Google Scholar]

- De Winter, J. C. F., Gosling, S. D and Potter, J.. 2016. Comparing the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients across distributions and sample sizes: a tutorial using simulations and empirical data. Psychological Methods, 21(3), 273–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo, M. H. and Gibson, S.. 1985. Teachers’ sense of efficacy: an important factor in school improvement. The Elementary School Journal, 86(2), 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, C. A. G., Tabares, S. J. and Orozco, M. C. V.. 2010. Burnout and coping strategies in teaching of primary and secondary. Psicología Desde El Caribe, 26(8), 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y. T.2016. Study on Yunnan Province special education teacher burnout and the relationship between personality traits. Master Degree Dissertation. Yunnan: Yunnan Normal University. [Google Scholar]

- Embich, J. L.2001. The relationship of secondary special education teachers' roles and factors that lead to professional burnout. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 24(1), 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, D. and Vandenberg, B.. 2010. Special education teacher burnout and act. International Journal of Special Education, 25(3), 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, W. J. G., Brouwers, A. and Tomic, W.. 2002. Burnout and self-efficacy: a study on teachers' beliefs when implementing an innovative educational system in the Netherlands. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(2), 227–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber, B. A.1991. Crisis in education: stress and burnout in the American teacher. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Fore, C., Martin, C. and Bender, W. N.. 2002. Teacher burnout in special education: The causes and the recommended solutions. The High School Journal, 86(1), 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, D. D. and Marolla, J.. 1976. Efficacious action and social approval as interacting dimensions of self-esteem: a tentative formulation through construct validation. Sociometry, 39(4), 324–341. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, I. A. and Farber, B. A.. 1992. Professional self-concept as a predictor of teacher burnout. The Journal of Educational Research, 86(1), 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, D. G. and Pierce, J. L.. 1998. Self-esteem and self-efficacy within the organizational context: an empirical examination. Group and Organization Management, 23(1), 48–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gecas, V. and Schwalbe, M. L.. 1983. Beyond the looking-glass self: social structure and efficacy-based self-esteem. Social Psychology Quarterly, 46(2), 77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gist, M. E.1987. Self-efficacy: implications for organizational behavior and human resource management. Academy of Management Review, 12(3), 472–485. [Google Scholar]

- Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Disabled Persons' Federation. 2007. Guangxi second national disabled persons sampling survey main data bulletin [EB/OL] (2019-06-11). http://www.gxzf.gov.cn/gggs/20071126-288970.shtml

- Handy, J. A.1988. Theoretical and methodological problems within occupational stress and burnout research. Human Relations, 41(5), 351–369. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, R. P. and Brown, T.. 2002. Coping strategies and the impact of challenging behaviors on special educators’ burnout. Mental Retardation, 40(2), 148–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F.2012. PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

- Hersey, P. and Blanchard, K. H.. 1993. Management of organizational behavior: Utilizing human resources. 6th ed.Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S. K.2016. Relationships among humour, self-esteem, and social support to burnout in school teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 19(1), 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. E.1989. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. E. and Freedy, J.. 1993. Conservation of resources: A general stress theory applied to burnout. In: Schaufeli W. B., Maslach C., & Marek T., eds. Professional burnout: recent development in theory and research. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis, pp. 115–-129. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. E. and Shirom, A.. 1993. Stress and burnout in the workplace: conservation of resources. In: Golombiewski T., ed. Handbook of organizational behavior. New York: Marcel Dekker, pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jennett, H. K., Harris, S. L. and Mesibov, G. B.. 2003. Commitment to philosophy, teacher efficacy, and burnout among teachers of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(6), 583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y. F. and Yu, X.. 1993. The self-esteem scale, SES. Chinese Journal of Mental Health (Supplement Extra Edition), 7(3), 251–252. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X. H., Zhao, S. Y. and Lan, W. J.. 2007. The separation between general and personal teaching efficacy and mental health of middle school teachers. Journal of Guizhou Normal University (Natural Science), 25(2), 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T. A. and Bono, J. E.. 2001. Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khezerlou, E.2017. Professional self-esteem as a predictor of teacher burnout across Iranian and turkish efl teachers. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 5(1), 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinos, C. M.2006. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Educators Survey among elementary and secondary school teachers in Cyprus. Stress and Health, 22(1), 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinos, C. M.2007. Job stressors, personality and burnout in primary school teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(1), 229–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korman, A. K.1971. Organizational achievement, aggression and creativity: some suggestions toward an integrated theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 6(5), 593–613. [Google Scholar]

- Korman, A. K.1976. Hypothesis of work behavior revisited and an extension. Academy of Management Review, 1(1), 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kupcewicz, E.2017. Global self-esteem and socio-demographic variables as predictors of burnout syndrome among Polish nurses. 7th EfCCNa CONGRESS, pp. 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, J., Lane, A. M. and Kyprianou, A.. 2004. Self-efficacy, self-esteem and their impact on academic performance. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 32(3), 247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y., Patterson, P. and Vega, L.. 2011. Perils to self-efficacy perceptions and teacher preparation quality among special education intern teachers. Teacher Education Quarterly, 38(2), 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. X.2013. Social factors of job burnout of teachers in special schools. Educational Research and Experiment, 31(4), 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B. Q. and Zhao, H. L.. 2015. The status and causes of job burnout among special education teachers in Heilongjiang. Journal of Suihua University, 33(4), 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. Y., Ban, Y. F. and Li, Z. Y.. 2011. The status and influencing factors of job burnout of special education teachers—take Guizhou Province as an example. Journal of Anshun University, 13(6), 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, S. J.2013. Teacher burnout and its relationships with academic optimism, teacher socialization, and teacher cohesiveness. ETD Collection for Fordham University: AAI3552664. https://fordham.bepress.com/dissertations/AAI3552664

- Major, A.2012. Job design for special education teachers. Retrieved from http://cie.asu.edu/ojs/index.php/cieatasu/article/viewfile/900/333

- Marsh, H. W.1993. Academic self-concept: theory measurement and research. In: Suls J., ed., Psychological perspectives on the self. Vol. 4. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 59–98. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C and Jackson, S. E.. 1984. Patterns of burnout among a national sample of public contact workers. Journal of Health & Human Resources Administration, 7(2), 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S.E. and Leiter, M.P.. 1996. Maslach burnout inventory manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, S.2016. The contexts within me: L2 self as a complex dynamic system. The dynamic interplay between context and the language learner. UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. 2019. National statistical bulletin on the development of education in 2018. Retrieved form http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/sjzl_fztjgb/201907/t20190724_392041.html.

- Peng, O., Huang, X., Wang, G., Zhang, R. and Bai, W.. 2018. The influence of the competency of special education teachers on occupational happiness: the intermediary effect of psychological capital. Journal of Chinese Special Education, 25(10), 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Pines, A. M.2004. Why are Israelis less burned out? European Psychologist, 9(2), 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Platsidou, M. and Agaliotis, I.. 2008. Burnout, job satisfaction and instructional assignment‐related sources of stress in Greek special education teachers. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 55(1), 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Polok, N. A.1990. Burnout in a high technology firm: the contribution of self-esteem and selected situational factors. Doctoral dissertation, University of Colorado at Boulder. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, L. A.2015. School-wide educator evaluation for improving school capacity and student achievement in high-poverty schools: year 1 of the school system improvement project. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 25(2–3), 90–108. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, S.2018. Teacher burnout: special education teachers' perspectives. Northcentral University: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M.1965. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Acceptance and commitment therapy. Measures Package, 61, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M.1979. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rosse, J. G., Boss, R. W., Johnson, A. E. and Crown, D. F.. 1991. Conceptualisation the role of selfesteem in the burnout process. Group and Organization Studies, 16, 428–451. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble, L. A., Toland, M. D., Birdwhistell, J. L., Mcgrew, J. H. and Usher, E. L.. 2013. Preliminary study of the autism self-efficacy scale for teachers (asset). Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(9), 1151–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarıçam, H. and Sakız, H.. 2014. Burnout and teacher self-efficacy among teachers working in special education institutions in turkey. Educational Studies, 40(4), 423–437. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B. and Bakker, A. B.. 2004. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B. and Taris, T. W.. 2005. The conceptualization and measurement of burnout: common ground and worlds apart the views expressed in work and stress commentaries are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of any other person or organization, or of the journal. Work and Stress, 19(3), 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R. and Hallum, S.. 2008. Perceived teacher self‐efficacy as a predictor of job stress and burnout: mediation analyses. Applied Psychology, 57(s1), 152–171. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R., Schmitz, G. S. and Tang, C.. 2000. Teacher burnout in Hong Kong and Germany: a cross-cultural validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping: An International Journal, 13(3), 309–326. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish, W. R.1996. Meta-analysis and the exploration of causal mediating processes: a primer of examples, methods, and issues. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrake, D. A.2013. A comparative study of administrator and special education teacher perceptions of special education teacher attrition and retention. Portland State University: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sherer, M., Maddux, J. E., Mercandante, B., Prentice-Dunn, S., Jacobs, B., & Rogers, R. W.. 1982. The self-efficacy scale: construction and validation. Psychological Reports, 51(2), 663–671. [Google Scholar]

- Shyman, E.2011. Examining mutual elements of job strain model and the effort-reward imbalance model among special education staff in the USA. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 39(3), 349–363. [Google Scholar]

- Skaalvik, E. M. and Skaalvik, S.. 2007. Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 611. [Google Scholar]

- Skaalvik, E. M and Skaalvik, S.. 2010. Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: a study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1059–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, N. A and LaPlante, S. F.. 2002. Burnout among special education teachers in self-contained cross-categorical classrooms. Teacher Education and Special Education, 25(1), 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.2013. A study on the relationship among burnout, teaching efficacy and social support of teachers in special education schools in Beijing. Physical Education, 5(2), 77–79 + 131. [Google Scholar]

- Tharenou, P.1979. Employee self-esteem: a review of the literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 15(3), 316–346. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, K. F.2002. The potential benefits of teacher efficacy doubts for educational reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski, L. and Gargiulo, R. M.. 1997. Occupational stress and burnout among special educators: a review of the literature. The Journal of Special Education, 31(3), 325–346. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.2010. Research on job burnout and related factors of secondary vocational teachers. Educational Theory and Practice, 28(6), 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. C., Qi, Y. J., Yu, R. R. and Zang, W. W.. 2016. Revision of Chinese Primary and Secondary School Teachers' Job Burnout Questionnaire. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24(5), 856–860. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y. Y., Noh, H., Shin, H., Lee, S. M.. 2015. A typology of burnout among Korean teachers. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 24(2), 309–318. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G. L., Xin, T. and Shen, J. L.. 1995. Teaching efficacy of teachers: research on structure and influencing factors. Journal of Psychology, 40(5), 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Yulianti, P., Ostrovsky Atomzeal, M. and Ayu Arina, N.. 2018. Burnout, self-efficacy and work satisfaction among special education teacher. KnE Social Sciences, 3(10), 1180–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Zabel, R. H. and Kay, Z. M.. 2001. Revisiting burnout among special education teachers: do age, experience, and preparation still matter? Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 24(2), 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang. Y. H. (2017). Characteristics and relationship of job burnout self-worth andteaching innovation of special education teachers Master Degree Dissertation,Zhejiang University of Technology Hangzhou [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. H. and Xiao, F.. 2009. Analytical Report of Teacher Burnout of Special School in Dan Dong Area. Journal of Schooling Studies, 6(7), 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D. F. and Shen, R. H.. 2013. Research on special education teacher's teaching efficacy, social support and job burnout. Journal of Bijie University, 31(10), 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. B.2009. A survey of teaching efficacy, job burnout, self-esteem and related relationship among physical education teachers in Hebei. Master Degree Dissertation, Shanghai: East China Normal University. [Google Scholar]